Published online Aug 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i22.6443

Peer-review started: March 9, 2021

First decision: April 24, 2021

Revised: May 7, 2021

Accepted: May 25, 2021

Article in press: May 25, 2021

Published online: August 6, 2021

Processing time: 140 Days and 17.5 Hours

In recent years, the rate of immunosuppressed patients has increased rapidly. Invasive fungal infections usually occur in these patients, especially those who have had hematological malignances and received chemotherapy. Fusariosis is a rare pathogenic fungus, it can lead to severely invasive Fusarium infections. Along with the increased rate of immune compromised patients, the incidence of invasive Fusarium infections has also increased from the past few years. Early diagnosis and therapy are important to prevent further development to a more aggressive or disseminated infection.

We report a case of a 19-year-old male acute B-lymphocytic leukemia patient with fungal infection in the skin, eyeball, and knee joint during the course of chemotherapy. We performed skin biopsy, microbial cultivation, and molecular biological identification, and the pathogenic fungus was finally confirmed to be Fusarium solani. The patient was treated with oral 200 mg voriconazole twice daily intravenous administration of 100 mg liposomal amphotericin B once daily, and surgical debridement. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor was administered to expedite neutrophil recovery. The disseminated Fusarium solani infection eventually resolved, and there was no recurrence at the 3 mo follow-up.

Our case illustrates the early detection and successful intervention of a systemic invasive Fusarium infection. These are important to prevent progression to a more aggressive infection. Disseminate Fusarium infection requires the systemic use of antifungal agents and immunotherapy. Localized infection likely benefits from surgical debridement and the use of topical antifungal agents.

Core Tip: Fusarium as a rare pathogenic fungus can lead to severely invasive fusariosis and is associated with high morbidity and with up to 70% mortality. The clinical manifestations of invasive Fusarium infection are varied; early diagnosis and proper therapies are essential. In such infections, the identification of fungal etiology is very important. Histopathological examination, microbial cultivation, antifungal susceptibility testing, and molecular biological identification are helpful for the diagnosis and treatment of this disease. In this case, the diagnosis was clear and the patient was successfully treated with positive efforts.

- Citation: Yao YF, Feng J, Liu J, Chen CF, Yu B, Hu XP. Disseminated infection by Fusarium solani in acute lymphocytic leukemia: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(22): 6443-6449

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i22/6443.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i22.6443

Fusariosis is the second common mold infection after aspergillosis[1]. Fusarium species are important plant pathogens causing a broad spectrum of infections, including superficial infections (keratitis and onychomycosis) and invasive or disseminated infections[2]. Agents of any type of fusariosis are mainly found in the following three species complexes: Fusarium solani (F. solani) complex (FSSC), Fusarium oxysporum complex, and Fusarium fujikuroi. Members of the FSSC cause the majority fusariosis cases of humans and are responsible for approximately two-thirds of all cases of fusariosis[1]. Disseminated Fusarium infection is a rare and serious fungal infection in immunocompromised patients, and clinical manifestations vary considerably[3]. The early diagnosis and treatment are quite difficult, and the mortality rate is estimated to be between 50% and 70% in adult patients. The remarkable intrinsic resistance of Fusarium species to most antifungal agents makes treatment more difficult. However, the optimal treatment for disseminated fusariosis has not been established[4]. Here, we describe the case of a 19-year-old male acute B-lymphocytic leukemia patient who had multiple skin lesions, endophthalmitis, and septic arthritis caused by F. solani infection during the course of chemotherapy.

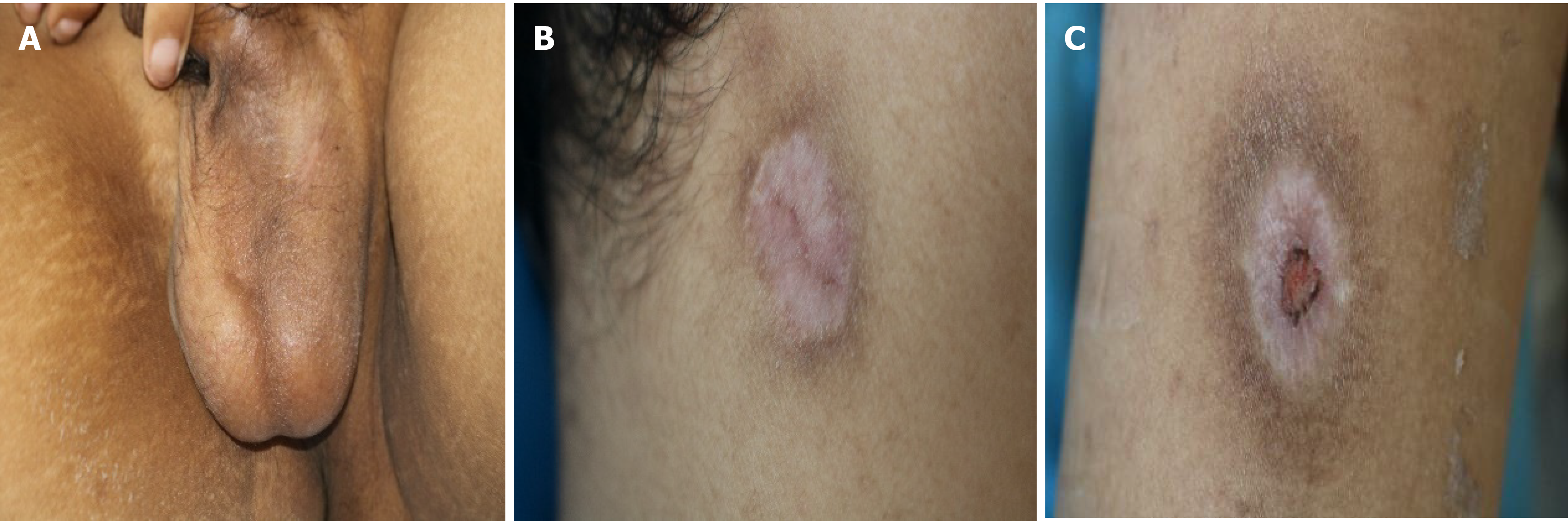

A 19-year-old male presented to the Department of Dermatology of our hospital complaining of multiple skin lesions of the right neck, right calf, and left scrotum, which showed ulcerated painful nodules with a necrotic center.

A 19-year-old male presented with swelling of the parotid gland and superficial lymphadenopathy for 2 wk and was admitted to our hospital. Through comprehensive examination, a diagnosis of acute B-lymphocytic leukemia was made. He was treated with BMF95 chemotherapy regimen (vindesine, daunorubicin, L-aspartase, and prednisone) according to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines and achieved complete remission. The major adverse event of the treatment was myelosuppression. He received regular injections of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) to increase the neutrophil count.

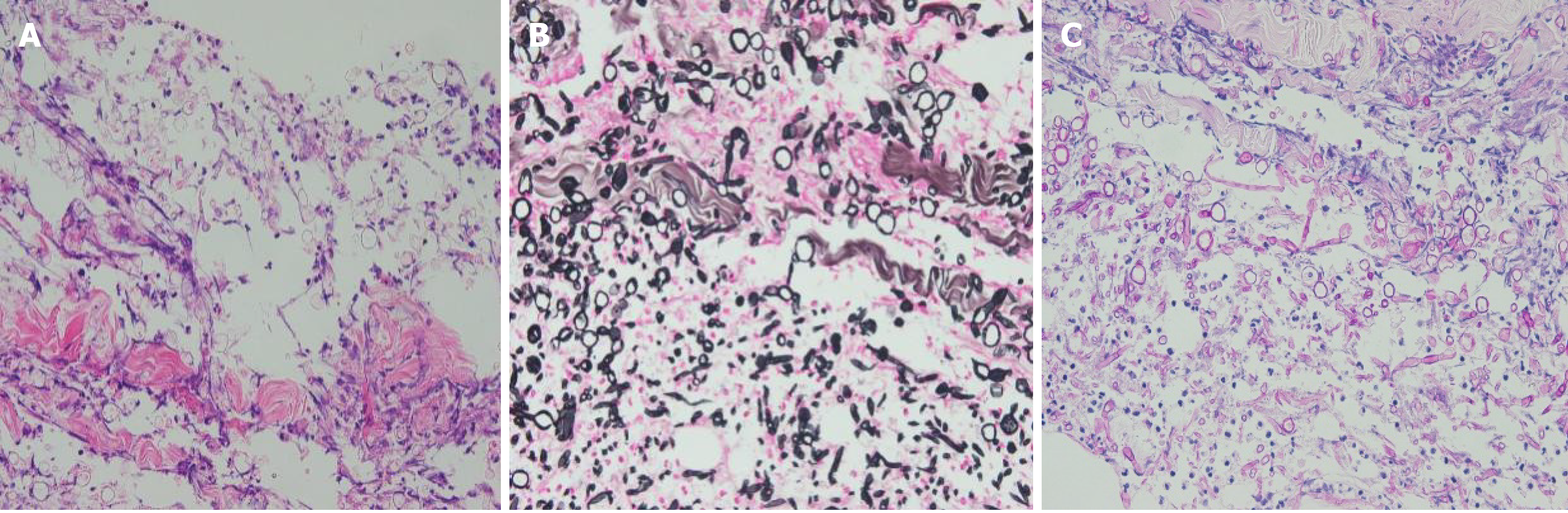

Five months later, he presented with unremitting fever during the fifth course of treatment. The highest body temperature was 41 ℃. The result of blood culture was Klebsiella pneumoniae. His chest computed tomography (CT) scan was negative. He received moxifloxacin, vancomycin, and teicoplanin to treat septicemia. After treatment, he still had intermittent fever. Considering the high possibility of fungal infection in this patient, he started prophylactic anti-fungal therapy with caspofungin. Twenty-five days later, he developed multiple skin lesions, including ulcerated painful nodules with a necrotic center of the right neck, right calf, and left scrotum (Figure 1). Blood culture and glactomannan (GM) test of serum samples were negative. At the same time, he underwent surgical resection of infected skin tissues. Additionally, the lesions on his neck and scrotum underwent pathological examination and microbial culture, and the results supported Fusarium spp. infection (Figures 2 and 3). Then, he was treated with oral voriconazole (200 mg) twice daily and intravenous administration of AmB (amphotericin B) liposome (100 mg) once daily. His fever promptly disappeared on the 2nd day of treatment. During the therapy, he received regular injections of G-CSF. Upon re-examination of the complete blood count, his absolute neutrophil count recovered to 0.9 × 109/L. On the 6th day of antifungal treatment, he developed left eyeball pain and conjunctival hemorrhage with blurred vision. A plain CT scan of the orbit showed that the lateral wall was slightly thicker and the lacrimal gland was slightly swollen. Fusarium was cultured from the vitreous drainage fluid of the left eyeball, and AmB local eye drops were added to the treatment. However, the pain in the left eyeball worsened, and he experienced gradual blindness. Vitrectomy of the left eye was performed on the 15th day of anti-fungal treatment. At the same time, the skin lesion gradually subsided. On the 18th day of anti-fungal treatment, he developed pain in the right knee joint, and ultrasound showed knee joint effusion. We performed joint puncture and the surgeon extracted 70 mL of yellow turbid liquid, and the fungus cultured was Fusarium. The articular cavity was continuously washed with saline (1000 mL) and amphotericin B liposome (10 mg), and after treatment, the arthritis resolved. Moreover, his final neutrophil count recovered to 1.7 × 109/L. He had no recurrence after 3 mo of follow-up.

The patient was diagnosed as acute B-lymphocytic leukemia 5 mo ago.

Patient denied family history of hereditary diseases.

Physical examination showed that there were multiple skin lesions in the right neck, right calf, and left scrotum, including ulcerated painful nodules with a necrotic center (Figure 1).

Complete blood count showed a hemoglobin level of 6.4 g/dL, white blood cell count of 0.21 × 109/L (neutrophil: 0.02 × 109/L), and platelet count of 82 × 109/L. The result of blood culture was Klebsiella pneumoniae. Serum GM test was negative.

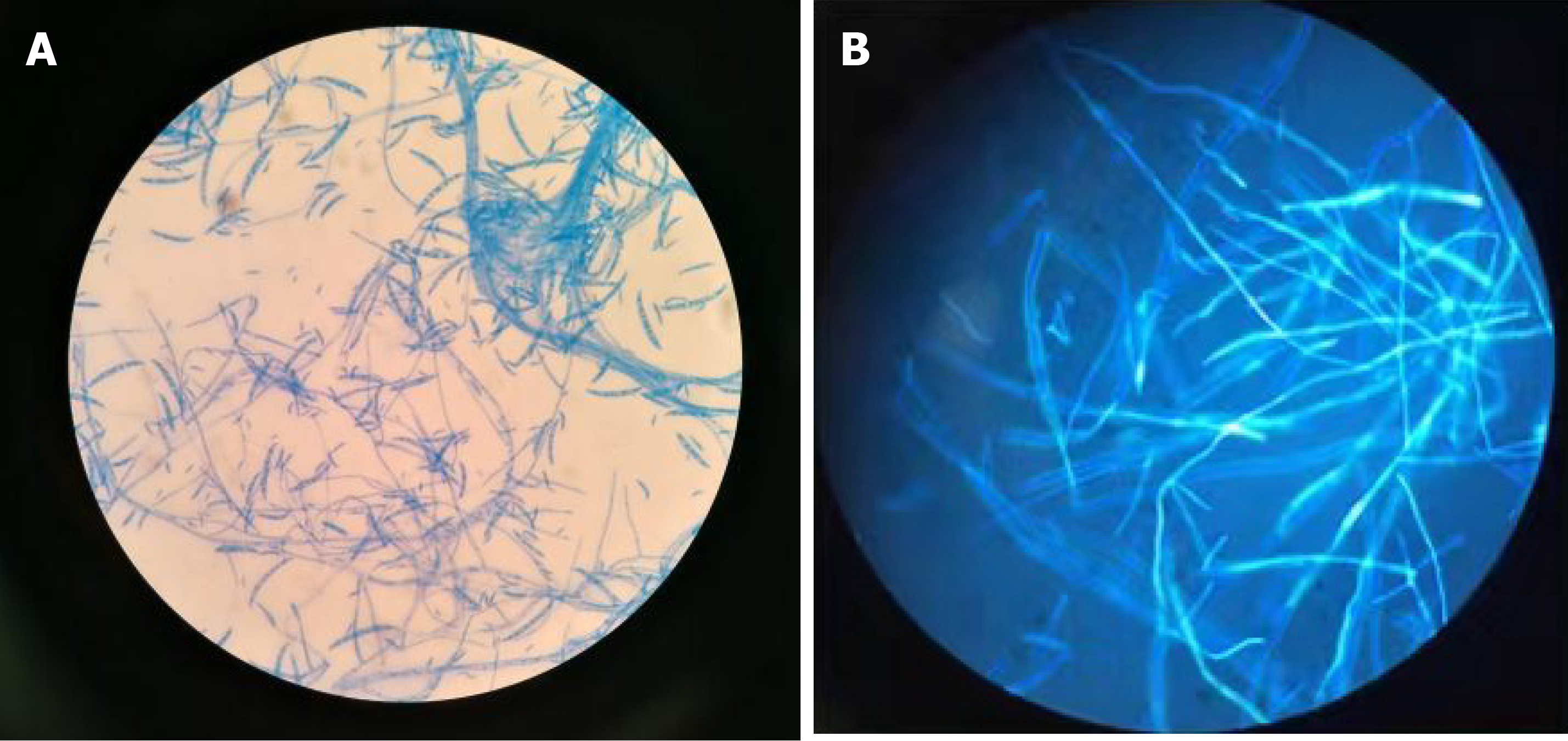

Biopsy of the neck skin lesion and microscopic examination for fungus showed the presence of fungal elements and confirmed Fusarium sp. infection (Figures 2 and 3). Fungal susceptibility assays showed an AmB minimum inhibitory concentration of 4 µg/mL and resistance to terbinafine, micafungin, posaconazole, and voriconazole. Thereafter, polymerase chain reaction followed by sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer region confirmed that the fungus belonged to the FSSC.

Vitreous drainage fluid of the left eyeball cultured Fusarium sp. Right knee joint liquid also cultured Fusarium sp. Blood culture and GM test of serum samples were negative.

Chest CT scan was negative. Plain CT scan of the orbit showed that the lateral wall was slightly thicker, and the lacrimal gland was slightly swollen.

Disseminated F. solani infection.

The patient was given systemic use of antifungal agents, oral voriconazole (200 mg) twice daily, intravenous administration of AmB liposome (100 mg) once daily, and regular injections of G-CSF to increase the neutrophil count. After surgical removal of skin and left eyeball lesions, local antifungal therapy was given. Extracted joint effusion was performed, and the articular cavity was continuously washed with saline (1000 mL) and AmB liposome (10 mg).

The skin lesions resolved, with pigmentation and crust (Figure 4). He had no recurrence after 3 mo of follow-up.

The most common risk factors of disseminated Fusarium infection in acute lymphocytic leukemia are prolonged neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count ≤ 0.5 × 109/L) due to intensification of cytotoxic chemotherapy and the wide spread use of corticosteroids and other immunosuppressive agents[5]. Clinical manifestations of invasive Fusarium infection vary considerably and often involve skin as well as lung or sinus lesions[6]. The most frequent pattern of disseminated disease is a combination of cutaneous lesions and positive blood cultures with or without involvement at other sites (the sinuses, lung, joint, and others)[7]. In many patients, skin lesions may be the first sign of a disseminated infection and are commonly seen in the early stages of the disease. It has been reported that 70% of patients often present with characteristic skin lesions involving multiple nodular and painful lesions, frequently with a necrotic center[8]. Pulmonary nodules have been reported in 80% of patients with respiratory symptoms, and nodules greater than 1 cm should raise the suspicion of invasive fungal infection[9]. Although some patients received broad-spectrum antifungal prophylaxis and underwent the most active antifungal agent treatment against this fungus, their clinical condition remained serious[10]. The worst disseminated fungal infections can trigger multiple organ failure and lead to patient death.

An early and definitive diagnosis requires isolation of Fusarium sp. from infected sites (the skin, sinuses, lungs, blood, and others) by direct microscopic examination or microorganism culture. There is a relatively high frequency of positive blood cultures (about 80%) for Fusarium sp.[11]. In this patient, the blood culture and GM test of serum samples were negative, probably because of the continuous prophylaxis anti-fungal treatment. Lung involvement is common in invasive fusariosis. The clinical presentation is nonspecific and includes dry cough and shortness of breath[12]. Chest CT is the imaging method in patients with pulmonary Fusarium infection[3]. The most common findings are nodules or masses but are nonspecific. Etiological diagnosis is critical, and until reliable non-invasive diagnostic approaches become available, invasive procedures, such as bronchoscopy with broncho-alveolar lavage and lung nodule biopsy, will continue to be necessary[1]. Skin biopsy of a nodule is necessary in patients with multiple skin lesions, and histopathological findings include branching septate hyaline hyphae with sporulation. Microorganism culture identification is important because Fusarium can product hyaline, crescent or banana-shaped, multicellular macroconidia[13]. However, different species may present the same structure, or the outcome may be negative. Given these difficulties, new approaches have been pursued[4]. Polymerase chain reaction and ribosomal RNA internal transcribed spacer sequencing can identify the species of Fusarium. These technologies hasten the identification of fungi and are more accurate[14]. Multilocus sequence typing is currently viewed as a promising new approach to diagnose fusariosis. Matrix-assisted desorption/ionization time of flight mass spectrometry is a promising new tool for rapid identification and classification of culture microorganisms based on their protein spectra[15].

Therapy for invasive fusariosis is a challenge, mainly because Fusarium shows high minimum inhibitory concentrations to antifungal agents[16]. Additionally, owing to the lack of clinical trials, there is no proven effective treatment regimen. In reported cases, the treatment of these diseases often depended on a combination of antifungals. In some cases, treatment should include surgical debridement. Voriconazole, AmB, and various combinations have been reported with varying success. Data on combination therapy for fusariosis, such as caspofungin plus AmB, voriconazole plus AmB, and voriconazole plus terbinafine, have been reported[17]. For immunocompromised patients, treatment should include voriconazole or AmB as initial therapy and posaconazole as salvage therapy. Localized infection, such as keratitis, is usually treated with topical antifungal treatment, and natamycin is the drug of choice. Skin lesions may be the source for disseminated and life-threatening Fusarium infections. Fungal growth might occur in compartments where insufficient antifungal drug concentrations are achieved, such as the joint and eyeball[5]. Local debridement should be performed, and topical antifungal agents should be used. Reversal of immunosuppression, especially the restoration of the neutrophil count, is essential for a successful therapeutic outcome[15].

Among acute lymphocytic leukemia patients, invasive fungal infections are very common. Candida and Aspergillus are the most common invasive fungal infection pathogens[5]. Fusarium, Zygomycetes sp., Alternaria sp., and Exserohilum sp. are less prevalent. The most frequent site of infection is the respiratory tract, including pulmonary, sinusal, or nasopharyngeal infections[18]. Fusarium infection has its own characteristics. Empiric antifungal treatment is usually AmB due to its broad spectrum coverage, then switched to other antifungals based on susceptibility results.

Our case illustrates the early detection and successful intervention of an invasive F. solani infection. Identifying the risk factors of invasive Fusarium infection and actively looking for the pathogen can help early diagnosis and treatment, which are important to prevent progression to a more aggressive or disseminated infection. In general, disseminated Fusarium infection requires the use of systemic agents and immunotherapy. Localized infection likely benefits from surgical debridement and the use of topical antifungal agents.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Dermatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Jameel PZ, Nwabo Kamdje AH S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Al-Hatmi AMS, Bonifaz A, Ranque S, Sybren de Hoog G, Verweij PE, Meis JF. Current antifungal treatment of fusariosis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2018;51:326-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tortorano AM, Richardson M, Roilides E, van Diepeningen A, Caira M, Munoz P, Johnson E, Meletiadis J, Pana ZD, Lackner M, Verweij P, Freiberger T, Cornely OA, Arikan-Akdagli S, Dannaoui E, Groll AH, Lagrou K, Chakrabarti A, Lanternier F, Pagano L, Skiada A, Akova M, Arendrup MC, Boekhout T, Chowdhary A, Cuenca-Estrella M, Guinea J, Guarro J, de Hoog S, Hope W, Kathuria S, Lortholary O, Meis JF, Ullmann AJ, Petrikkos G, Lass-Flörl C; European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Fungal Infection Study Group; European Confederation of Medical Mycology. ESCMID and ECMM joint guidelines on diagnosis and management of hyalohyphomycosis: Fusarium spp., Scedosporium spp. and others. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20 Suppl 3:27-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 298] [Cited by in RCA: 345] [Article Influence: 31.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Liu YS, Wang NC, Ye RH, Kao WY. Disseminated Fusarium infection in a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2014;7:334-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nucci M, Anaissie E. Fusarium infections in immunocompromised patients. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:695-704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 646] [Cited by in RCA: 668] [Article Influence: 37.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Garnica M, da Cunha MO, Portugal R, Maiolino A, Colombo AL, Nucci M. Risk factors for invasive fusariosis in patients with acute myeloid leukemia and in hematopoietic cell transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:875-880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Sheela S, Ito S, Strich JR, Manion M, Montemayor-Garcia C, Wang HW, Oetjen KA, West KA, Barrett AJ, Parta M, Gea-Banacloche J, Holland SM, Hourigan CS, Lai C. Successful salvage chemotherapy and allogeneic transplantation of an acute myeloid leukemia patient with disseminated Fusarium solani infection. Leuk Res Rep. 2017;8:4-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Chan TS, Au-Yeung R, Chim CS, Wong SC, Kwong YL. Disseminated fusarium infection after ibrutinib therapy in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Ann Hematol. 2017;96:871-872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ricna D, Lengerova M, Palackova M, Hadrabova M, Kocmanova I, Weinbergerova B, Pavlovsky Z, Volfova P, Bouchnerova J, Mayer J, Racil Z. Disseminated fusariosis by Fusarium proliferatum in a patient with aplastic anaemia receiving primary posaconazole prophylaxis - case report and review of the literature. Mycoses. 2016;59:48-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Delia M, Monno R, Giannelli G, Ianora AA, Dalfino L, Pastore D, Capolongo C, Calia C, Tortorano A, Specchia G. Fusariosis in a Patient with Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Mycopathologia. 2016;181:457-463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rosa PDD, Ramirez-Castrillon M, Borges R, Aquino V, Meneghello Fuentefria A, Zubaran Goldani L. Epidemiological aspects and characterization of the resistance profile of Fusarium spp. in patients with invasive fusariosis. J Med Microbiol. 2019;68:1489-1496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ersal T, Al-Hatmi AS, Cilo BD, Curfs-Breuker I, Meis JF, Özkalemkaş F, Ener B, van Diepeningen AD. Fatal disseminated infection with Fusarium petroliphilum. Mycopathologia. 2015;179:119-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Shen Q, Song XM, Xu XP, Wang JM. [Pulmonary fungal infection in malignant hematological diseases: an analysis of 14 cases]. Zhongguo Shi Yan Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2005;13:1125-1127. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Petit A, Tabone MD, Moissenet D, Auvrignon A, Landman-Parker J, Boccon-Gibod L, Leverger G. [Disseminated fusarium infection in two neutropenic children]. Arch Pediatr. 2005;12:1116-1119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Herkert PF, Al-Hatmi AMS, de Oliveira Salvador GL, Muro MD, Pinheiro RL, Nucci M, Queiroz-Telles F, de Hoog GS, Meis JF. Molecular Characterization and Antifungal Susceptibility of Clinical Fusarium Species From Brazil. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Nucci M, Garnica M, Gloria AB, Lehugeur DS, Dias VC, Palma LC, Cappellano P, Fertrin KY, Carlesse F, Simões B, Bergamasco MD, Cunha CA, Seber A, Ribeiro MP, Queiroz-Telles F, Lee ML, Chauffaille ML, Silla L, de Souza CA, Colombo AL. Invasive fungal diseases in haematopoietic cell transplant recipients and in patients with acute myeloid leukaemia or myelodysplasia in Brazil. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19:745-751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Pujol I, Guarro J, Gené J, Sala J. In-vitro antifungal susceptibility of clinical and environmental Fusarium spp. strains. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;39:163-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lewis RE, Wurster S, Beyda ND, Albert ND, Kontoyiannis DP. Comparative in vitro pharmacodynamic analysis of isavuconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole against clinical isolates of aspergillosis, mucormycosis, fusariosis, and phaeohyphomycosis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;95:114861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hardak E, Fuchs E, Geffen Y, Zuckerman T, Oren I. Clinical Spectrum, Diagnosis and Outcome of Rare Fungal Infections in Patients with Hematological Malignancies: Experience of 15-Year Period from a Single Tertiary Medical Center. Mycopathologia. 2020;185:347-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |