Published online Jul 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i21.6170

Peer-review started: March 29, 2021

First decision: April 28, 2021

Revised: May 7, 2021

Accepted: May 24, 2021

Article in press: May 24, 2021

Published online: July 26, 2021

Processing time: 114 Days and 5.6 Hours

Neoplastic pericardial effusion (NPE) is a rare consequence of rectal cancer and carries a poor prognosis. Optimal management has yet to be determined. Fruquintinib is an oral anti-vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor approved by the China Food and Drug Administration in September 2018 as third-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer.

Herein, we report an elderly patient with NPE from rectal cancer who responded to the use of fruquintinib. In March 2015, a 65-year-old Chinese woman diagnosed with KRAS-mutated adenocarcinoma of the rectum was subjected to proctectomy, adjuvant concurrent chemoradiotherapy, and adjuvant chemotherapy. By October 2018, a mediastinal mass was detected via computed tomography. The growth had invaded parietal pericardium and left hilum, displaying features of rectal adenocarcinoma in a bronchial biopsy. FOLFIRI and FOLFOX chemotherapeutic regimens were administered as first- and second-line treatments. After two cycles of second-line agents, a sizeable pericardial effusion resulting in tamponade was drained by pericardial puncture. Fluid cytology showed cells consistent with rectal adenocarcinoma. Single-agent fruquintinib was initiated on January 3, 2019, as a third-line therapeutic. Ten cycles were delivered before the NPE recurred and other lesions progressed. The recurrence-free interval for NPE was 9.2 mo, attesting to the efficacy of fruquintinib. Ultimately, the patient entered a palliative care unit for best supportive care.

Fruquintinib may confer good survival benefit in elderly patients with NPEs due to rectal cancer.

Core Tip: Neoplastic pericardial effusion (NPE) is a rare consequence of rectal cancer and carries a poor prognosis. We report an elderly patient with NPE from rectal cancer who responded to the use of fruquintinib. In March 2015, a 65-year-old Chinese woman diagnosed with adenocarcinoma of the rectum. By October 2018, FOLFIRI and FOLFOX chemotherapeutic regimens were administered as first- and second-line treatments. After two cycles of second-line agents, she was diagnosed with NPE. Single-agent fruquintinib was initiated as a third-line therapeutic. The recurrence-free interval for NPE was 9.2 mo, attesting to the efficacy of fruquintinib.

- Citation: Zhang Y, Zou JY, Xu YY, He JN. Fruquintinib beneficial in elderly patient with neoplastic pericardial effusion from rectal cancer: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(21): 6170-6177

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i21/6170.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i21.6170

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer diagnosed worldwide and ranks fourth in global cancer mortality, accounting for an estimated 1.4 million new cases and 700,000 deaths in 2012[1]. Metastasis to the heart is rare, one autopsy series showing a prevalence of 1.4%-2%, and most often involves pericardium[2]. To date, only seven cases of neoplastic pericardial effusion (NPE) due to CRC have been reported in the English literature, four of them stemming from rectal cancer[3-6].

NPE typically indicates advanced disease and carries a poor prognosis[7]. Pericardiocentesis alone is the requisite emergency procedure to palliate life-threatening symptoms. Pericardiectomy, locoregional or systemic treatments, and best supportive care (BSC) may help prevent recurrences of NPE. In a retrospective study, median overall survival (OS) times of various treatment strategies were as follows: (1) Systemic therapy alone, 5 mo; (2) Systemic plus locoregional therapy, 2.1 mo; and (3) Locoregional therapy ± BSC, 1.6 mo[8].

The novel anti-vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) fruquintinib (Elunate®, Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, IN, United States) has been approved by China Food and Drug Administration since September 2018. It is indicated in past recipients of at least two standard therapies for metastatic CRC (including fluoropyrimidine, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan), with or without prior use of VEGF inhibitors or epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors[9]. This TKI is highly selectively for VEGFR-1, -2, and -3[10]. In the FRESCO phase 3 trial, fruquin

Herein, we describe an elderly woman with NPE due to rectal cancer who bene

A 68-year-old Chinese woman with rectal adenocarcinoma suddenly experienced dyspnea and tachycardia.

In March 2015, the patient received a diagnosis rectal adenocarcinoma. She had been troubled by constipation for approximately 2 years, claiming intermittent hemato

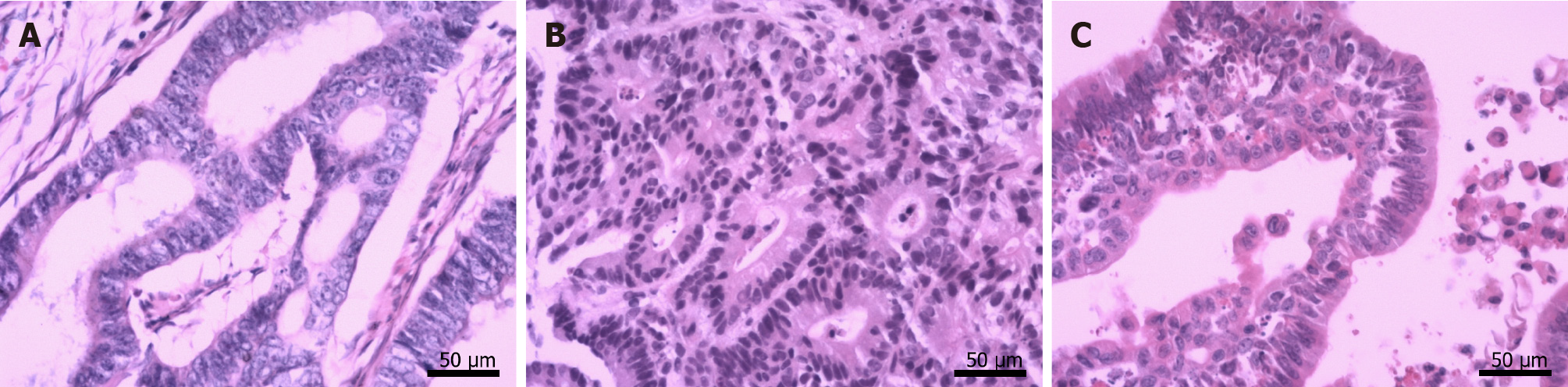

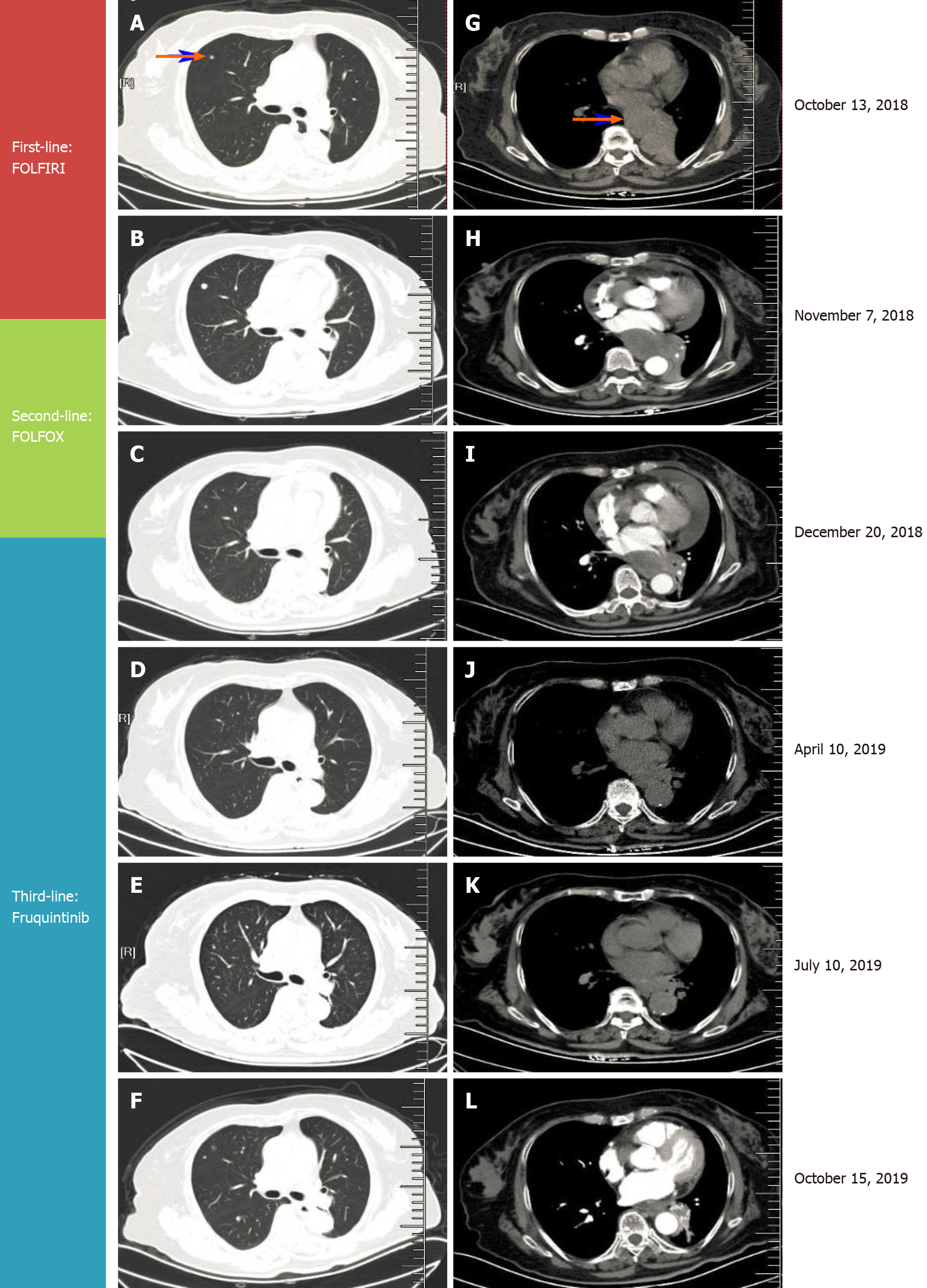

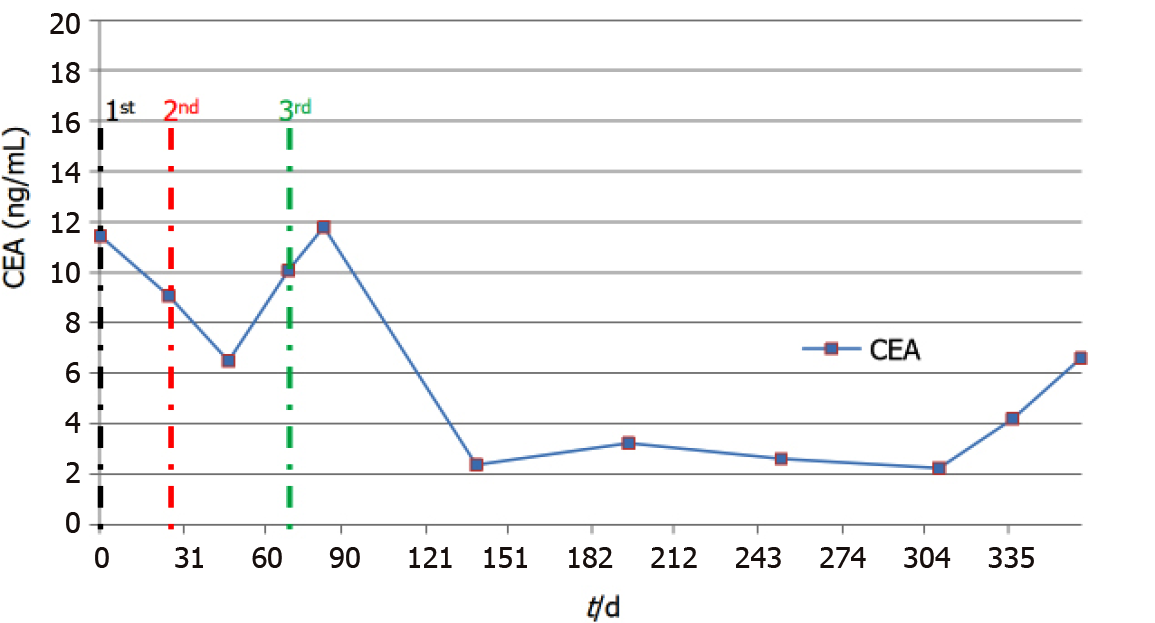

By October 2018, frequent bouts of cough and chest tightness prompted her return to the hospital. Chest computed tomography (CT) of October 13 showed a mediastinal mass (6.7 cm × 5.0 cm) invading parietal pericardium and left hilum, left obstructive atelectasis, and a metastatic nodule of right lung (Figure 2A and G). A bronchial biopsy was consistent with metastatic rectal cancer, proving positive for CDX2 protein and villin but negative for Napsin A and thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) in immunostained preparations (Figure 1B). The patient’s serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level was 11.44 ng/mL (Figure 3), and her condition was fair [Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 1]. Based on CT and histologic findings, the diagnosis was stage IV rectal cancer, with mediastinal and lung metastases. A first-line regimen of irinotecan plus 5-fluorouracil/Leucovorin (FOLFIRI) was therefore begun. At the end of the first cycle, the patient experienced grade 3 nausea and vomiting, which abated through parenteral nutrition. On November 7, 2018, a repeat CT scan showed progression of both mediastinal (8.2 cm × 4.4 cm) and right lung lesions, with some accumulation of pericardial fluid (Figure 2B and H). This qualified as progressive disease (PD) by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST), despite a drop in serum CEA level (9.08 ng/mL) (Figure 3).

During November 2018, the patient began a second-line FOLFOX regimen, barely completing two cycles before the abrupt onset of dyspnea and tachycardia on December 20, 2018.

The patient had hypertension.

The patient had no history of smoking, drinking, or familial cancers.

The patient’s temperature was 37.0 °C, heart rate was 130 bpm, respiratory rate was 24 breaths per minute, blood pressure was 90/60 mmHg and oxygen saturation in room air was 95%. The clinical examination revealed jugular venous distention and muted heart sounds were evident.

Other parameters (myocardial enzymes, electrocardiogram) were normal.

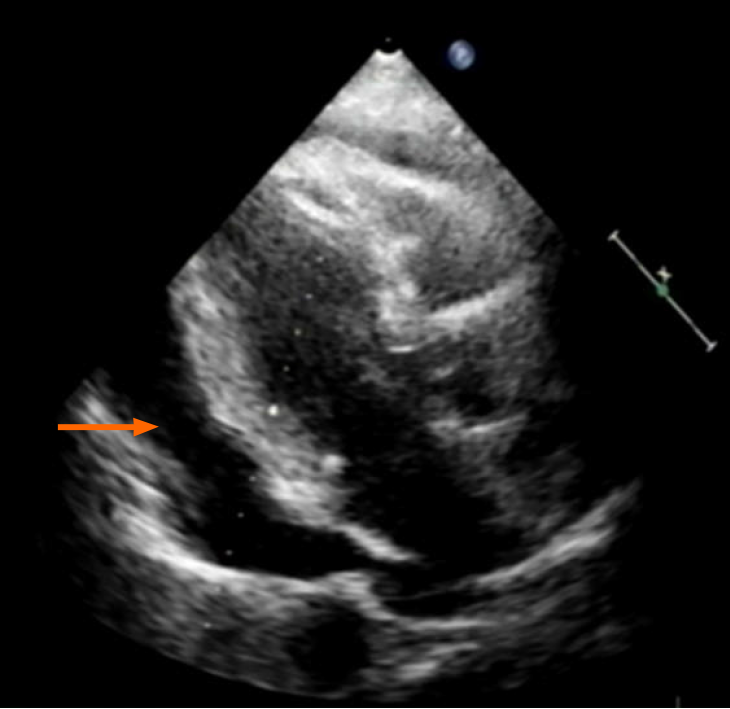

Echocardiography disclosed a voluminous pericardial effusion, reduced left ventri

Ultrasound-guided pericardial puncture was performed at once, withdrawing 800 mL of bloody fluid. The patient’s discomfort readily dissipated, her ECOG performance status rebounding from 2 to 1. Fluid cytology confirmed tumor-derived cells, later found positive for CEA and CDX2 and negative for TTF-1 by immunostains, again compatible with metastatic rectal cancer (Figure 1C).

The final diagnosis of the case was NPE due to rectal cancer.

NPE was established, indicating PD (Figure 2C and I) and second-line regimen failure despite shrinkage of mediastinal (5.6 cm × 3.6 cm) and right lung metastases by CT.

On January 3, 2019, the patient began a third-line regimen of single-agent fru

By October 9, 2019, there was overt CT evidence of disease progression, including recurrent NPE, left pulmonary atelectasis, and regrowth of the right lung nodule (Figure 2F and L). An upturn in CEA level (6.59 ng/ mL) (Figure 3) and worsening of ECOG performance status (1→2) were also apparent. We informed the patient of ongoing events, advising her of new therapeutic (i.e. local radiotherapy plus chemo

NPE occurs in 5%-15% of patients with advanced cancer, complicating therapeutic strategies[12]. It is often a secondary phenomenon due to metastasis. In a series of patient autopsies, pericardial metastasis resulted from lung cancer (35%), breast cancer (25%), lymphoma or leukemia (15%), and other malignancies (i.e. esophageal cancer, Kaposi’s sarcoma, or melanoma)[13-15]. Pericardial metastasis may result from either direct or blood vascular/Lymphatic spread[16]. Given the inherent lymphatic and venous return of rectal cancers, they often metastasize to lymph nodes, liver, or lungs and rarely involve pericardium[2].

Clinical manifestations of NPE may vary considerably or be absent at times for incidental discovery in sudden deaths. Dyspnea, orthopnea, pain, edema, or even hemoptysis may accompany sizeable effusions. During clinical examinations, jugular venous distention, hepatomegaly, muffling of heart sounds, rubs/murmurs, or electrocardiographic changes are encountered[15]. In a small percentage of cases, cardiac tamponade may ensue[17].

Echocardiography, CT, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), are generally used to detect NPE. Because echocardiography is readily available, inexpensive, and free of ionizing radiation, it is deemed the best imaging technique for this purpose[18], enabling both comprehensive gauging of hemodynamic effects imposed by effusions (including cardiac tamponade) and continuous monitoring of pre- and post-treatment fluid volumes. CT and MRI are clearly advantageous for accurate pinpointing of pericardial tumors and assessing adjacent cardiac and non-cardiac structural effects[19]. On the other hand, fluid cytology or pericardial biopsy is essential for a definitive diagnosis of malignancy. Immunohistochemistry is frequently needed to help characterize the antigenicity and nature of cells[20]. In this patient, tumor-derived cells were indeed present in the fluid collected. By comparing outcomes of immunostained cytologic and biopsy specimens, both pericardial and mediastinal manifestations were similarly traced to rectal cancer.

Managing NPE is focused on symptom relief and prevention of recurrence. Pericardiocentesis has dual roles (diagnostic and therapeutic) in symptomatic patients. Without additional treatment, however, NPE will recur at a high rate (up to 40%)[21]. Pericardiectomy, pericardial windows, and sclerotherapy are typically used to prevent recurrent symptomatic effusions[22]; but antineoplastic treatments, including che

In the past decade, targeted molecular therapy has become a promising strategy for effective clinical treatment of NPE due to various tumors: Pericardial perfusion of bevacizumab, a VEGF inhibitor (median OS, 168 d; range, 22-224 d), as one example[23]. Panitumumab is an anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody used to successfully treat cardiac metastasis of colonic adenocarcinoma[24], and the anti-EGFR TKI, gefitinib, has shown good anti-tumor effect against NPE linked to adenocarcinoma of the lung. Once initiated in our patient, the time-to-recurrence of NPE was 279 d for fruquintinib. It surpassed bevacizumab in progression-free survival and was well tolerated by an elderly woman with a high ECOG score. The convenient oral formulation also limits potential infectious complications of otherwise invasive therapies. We believe this is the first reported use of an anti-VEGFR TKI in effectively treating NPE due to rectal cancer. This novel molecular agent may well herald a new strategy for targeting NPE in patients with CRC.

NPE is rarely caused by rectal cancer but must be considered if cardiopulmonary symptoms and a voluminous pericardial effusion coexist. Fruquintinib may provide good survival benefit in elderly patients with NPE due to rectal cancer.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Mikulic D S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Yuan YY

| 1. | Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359-E386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20108] [Cited by in RCA: 20485] [Article Influence: 2048.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (19)] |

| 2. | Choufani EB, Lazar HL, Hartshorn KL. Two unusual sites of colon cancer metastases and a rare thyroid lymphoma. Case 2. Chemotherapy-responsive right artial metastasis from colon carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3574-3575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chen JL, Huang TW, Hsu PS, Chao-Yang, Tsai CS. Cardiac tamponade as the initial manifestation of metastatic adenocarcinoma from the colon: a case report. Heart Surg Forum. 2007;10:E329-E330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kwon JT, Lee DH, Jung TE, Gu MJ. Epicardial metastasis of rectal neuroendocrine tumour. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;46:504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhu H, Booth CN, Reynolds JP. Clinical presentation and cytopathologic features of malignant pericardial cytology: a single institution analysis spanning a 29-year period. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2015;4:203-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ben Yosef R, Warner E, Gez E, Catane R. Malignant pericardial effusion associated with metastatic rectal cancer: case report. J Chemother. 1989;1:342-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gornik HL, Gerhard-Herman M, Beckman JA. Abnormal cytology predicts poor prognosis in cancer patients with pericardial effusion. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5211-5216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Di Liso E, Menichetti A, Dieci MV, Ghiotto C, Banzato A, Bianchi A, Pintacuda G, Padovan M, Nappo F, Cumerlato E, Miglietta F, Mioranza E, Zago G, Corti L, Guarneri V, Conte P. Neoplastic Pericardial Effusion: A Monocentric Retrospective Study. J Palliat Med. 2019;22:691-695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Burki TK. Fruquintinib for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:e388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zhang Y, Zou JY, Wang Z, Wang Y. Fruquintinib: a novel antivascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor for the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:7787-7803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Li J, Qin S, Xu RH, Shen L, Xu J, Bai Y, Yang L, Deng Y, Chen ZD, Zhong H, Pan H, Guo W, Shu Y, Yuan Y, Zhou J, Xu N, Liu T, Ma D, Wu C, Cheng Y, Chen D, Li W, Sun S, Yu Z, Cao P, Chen H, Wang J, Wang S, Wang H, Fan S, Hua Y, Su W. Effect of Fruquintinib vs Placebo on Overall Survival in Patients With Previously Treated Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: The FRESCO Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2018;319:2486-2496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 279] [Article Influence: 39.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ghosh AK, Crake T, Manisty C, Westwood M. Pericardial Disease in Cancer Patients. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2018;20:60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Buck M, Ingle JN, Giuliani ER, Gordon JR, Therneau TM. Pericardial effusion in women with breast cancer. Cancer. 1987;60:263-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | HANFLING SM. Metastatic cancer to the heart. Review of the literature and report of 127 cases. Circulation. 1960;22:474-483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Adenle AD, Edwards JE. Clinical and pathologic features of metastatic neoplasms of the pericardium. Chest. 1982;81:166-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Katz WE, Ferson PF, Lee RE, Killinger WA, Thompson ME, Gorcsan J 3rd. Images in cardiovascular medicine. Metastatic malignant melanoma to the heart. Circulation. 1996;93:1066. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Levitan Z, Kaplan AL, Gordon AN. Survival after malignant pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade in advanced ovarian cancer. South Med J. 1990;83:241-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Refaat MM, Katz WE. Neoplastic pericardial effusion. Clin Cardiol. 2011;34:593-598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Maleszewski JJ, Anavekar NS. Neoplastic Pericardial Disease. Cardiol Clin. 2017;35:589-600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Gupta RK, Kenwright DN, Fauck R, Lallu S, Naran S. The usefulness of a panel of immunostains in the diagnosis and differentiation of metastatic malignancies in pericardial effusions. Cytopathology. 2000;11:312-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Tsang TS, Seward JB, Barnes ME, Bailey KR, Sinak LJ, Urban LH, Hayes SN. Outcomes of primary and secondary treatment of pericardial effusion in patients with malignancy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:248-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lestuzzi C, Berretta M, Tomkowski W. 2015 update on the diagnosis and management of neoplastic pericardial disease. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2015;13:377-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chen D, Zhang Y, Shi F, Zhu H, Li M, Luo J, Chen K, Kong L, Yu J. Intrapericardial bevacizumab safely and effectively treats malignant pericardial effusion in advanced cancer patients. Oncotarget. 2016;7:52436-52441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Tsujii Y, Hayashi Y, Maekawa A, Fujinaga T, Nagai K, Yoshii S, Sakatani A, Hiyama S, Shinzaki S, Iijima H, Takehara T. Cardiac metastasis from colon cancer effectively treated with 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (modified FOLFOX6) plus panitumumab: a case report. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |