Published online Jul 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i21.6138

Peer-review started: March 26, 2021

First decision: April 28, 2021

Revised: May 7, 2021

Accepted: May 24, 2021

Article in press: May 24, 2021

Published online: July 26, 2021

Processing time: 116 Days and 16.7 Hours

Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis (EPS) is hard to diagnose because of nonspecific symptoms and signs. It is a general consensus that EPS is classified as primary and secondary. There have been several studies discovering some high-risk factors such as liver cirrhosis, of which AMA-M2 is a biomarker, and intra-abdominal surgery such as laparoscopic surgery. Imaging studies help to diagnose EPS and exploratory laparotomy might be an alternative if imaging fails. Nowadays, laparotomy plays a key role in treating EPS, especially when medical treatments do not work and medical therapy fails to ease patients’ symptoms.

A 58-year-old man complained of unexplained vomiting and abdominal distension 2 mo after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Increased alkaline phosphatase and liver enzymes were discovered. An autoimmune liver disease test showed that AMA-M2 was positive. A gastroscopy revealed bile reflux gastritis. A magnetic resonance imaging scan showed a slight dilatation of the intrahepatic bile duct. A colonoscopy showed that there was a mucosal eminence lesion in the sigmoid colon (24 cm away from the anus), with a size of 3 cm × 3 cm and erosive surface. At last, the small intestine and the stomach were found to be encased in a cocoon-like membrane during the surgery. The membrane was dissected and adhesiolysis was done to release the trapped organs. The patient recovered and was discharged 44 d after the operation, and there was no recurrence during a follow-up period of 3 mo.

AMA-M2 is a marker of primary biliary sclerosis and may help to make a preoperative diagnosis of EPS.

Core Tip: Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis (EPS) is a kind of occult and potentially dangerous disease that is hard to diagnose and cure. The specific etiology of EPS is still a mystery, but there have been several cases indicating that liver cirrhosis is a high-risk factor for EPS. This article aims to emphasize that AMA-M2, which is a biochemical marker of primary biliary cirrhosis, is possible for preoperative diagnosis of EPS.

- Citation: Yin MY, Qian LJ, Xi LT, Yu YX, Shi YQ, Liu L, Xu CF. Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis in an AMA-M2 positive patient: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(21): 6138-6144

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i21/6138.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i21.6138

Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis (EPS) is a kind of occult and potentially dangerous disease that is hard to diagnose and cure. It was first named “peritonitis chronica fibrosa incapsulata” by Owtschinnikow in 1907[1]. EPS, also called abdominal cocoon, is characterized by a white, thick (or thin) fibrous membrane encapsulating the small intestine or other intraabdominal organs[2]. Nowadays, it is widely believed that there are two kinds of etiological hypotheses, idiopathic and secondary. And in secondary EPS, peritoneal dialysis is the most common predisposing factor[3]. Generally, individuals with EPS show nonspecific symptoms and signs. Some patients may suffer from unexplained malnutrition for several years[4], while others may present symptoms of the digestive system such as bellyache, diarrhea, nausea, and emesis. There has been no gold standard for the diagnosis of EPS to date. Relatively, laparoscopy or laparotomy plays a key role because they can diagnose and treat EPS at the same time[5].

Herein, we present a case of EPS characterized by nausea and emesis. The patient underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) 2 mo before symptoms appeared. It is worth noting that an autoimmune liver disease test showed that AMA-M2 was positive, which is a serum antibody that is often present in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. The written informed consent for the publication of this case was obtained from the patient. The timeline about the process of the diagnosis and treatment is shown as Supplementary Figure 1.

Intermittent nausea and emesis for more than 20 d.

A 58-year-old man, with intermittent nausea and emesis for more than 20 d, was admitted to our gastroenterology department. He complained that abdominal distension could be relieved after vomiting yellow gastric contents. No diarrhea, belching, or fever was found.

Two months ago, the patient experienced a LC at a local hospital and postoperative pathology showed chronic calculous cholecystitis. One month after the surgery, his ultrasonography indicated excessive intestinal gas. Other imaging studies like computed tomography (CT) showed no significant difference with the ultrasound findings.

The patient lived in Suzhou, China. He did not smoke and was not addicted to alcohol. No relevant family history was reported.

On physical examination, a little muscle tension was palpated around the bellybutton and no other positive signs were observed.

Increased alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and liver enzymes like alanine transaminase and aspartate aminotransferase were discovered. A fecal occult blood test was positive. A laboratory study regarding the autoimmune liver disease test was done to identify the causes of liver injury and revealed that AMA-M2 was positive.

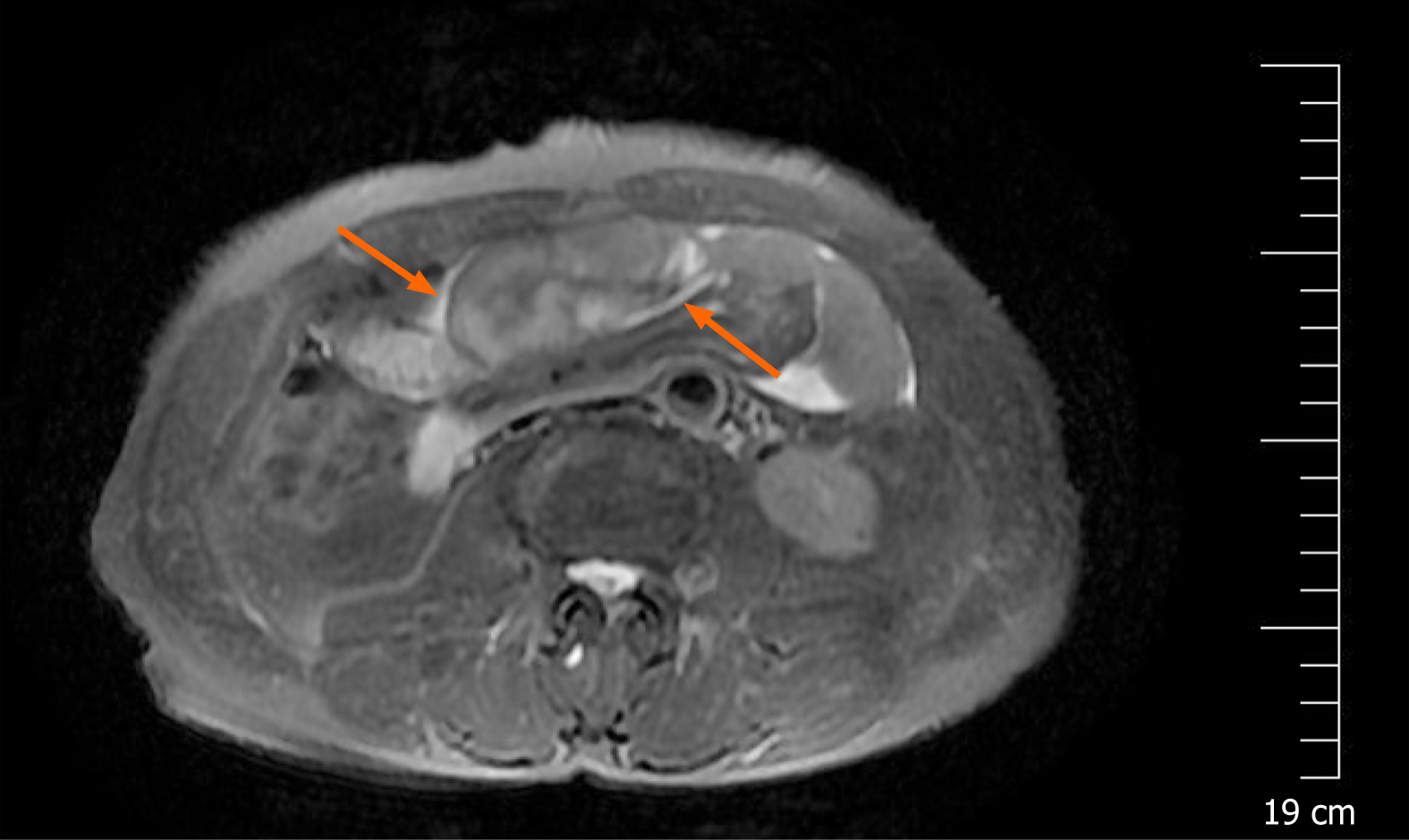

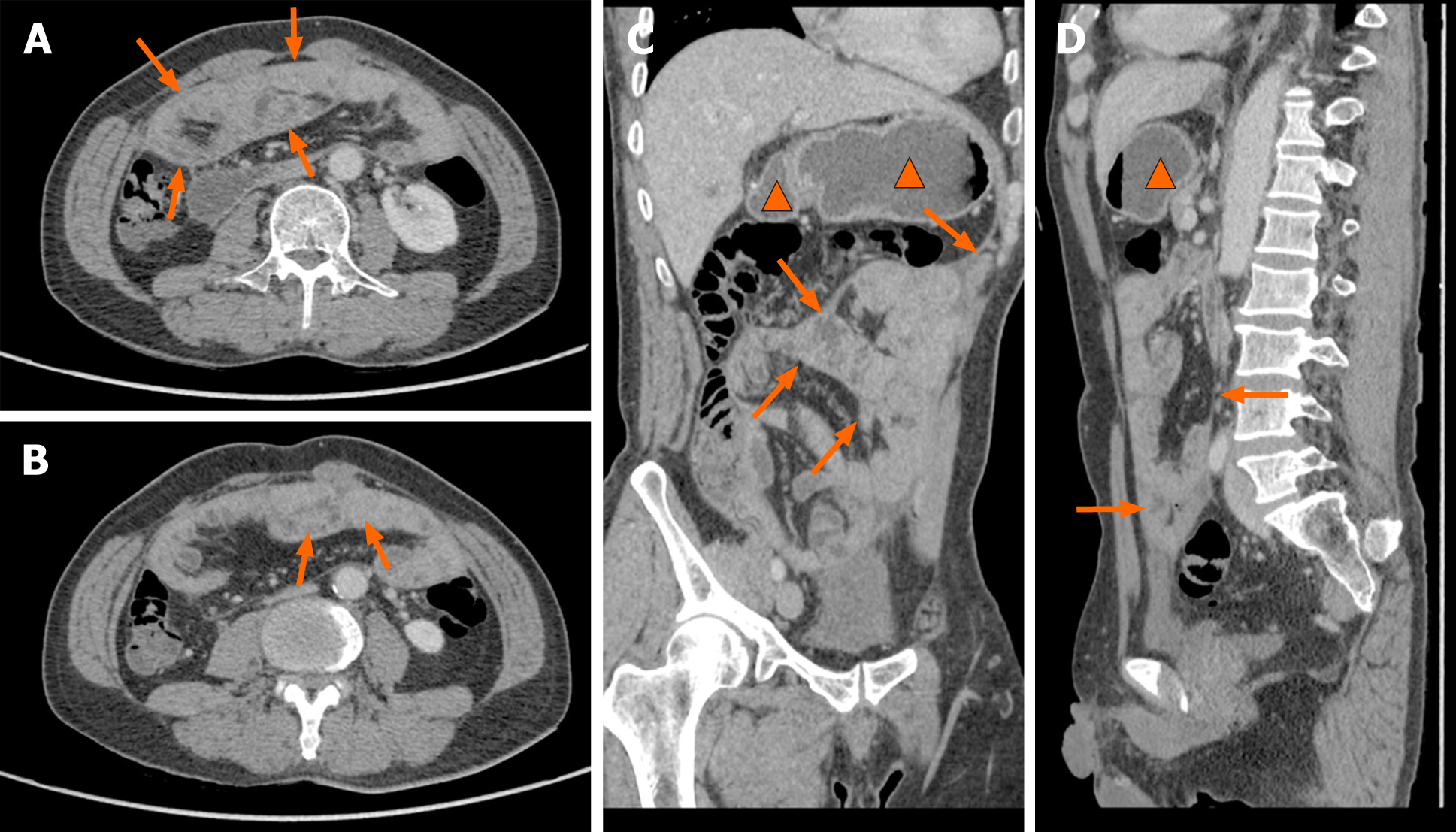

A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan showed a slight dilatation of the intrahepatic bile duct (Figure 1). Abdominal plain films showed much gas in the small intestine. A gastroscopy revealed erosive gastritis and bile reflux gastritis. An abdominal contrast-enhanced CT scan revealed that the gastric cavity and the duodenal lumen were dilated with fluid retention, the proximal jejunal wall thickened with a little exudation surrounding the mesentery, and the adjacent greater omentum thickened with a little effusion (Figure 2). A colonoscopy was added, showing that there was a mucosal eminence lesion in the sigmoid colon (24 cm away from the anus), with a size of 3 cm × 3 cm and erosive surface.

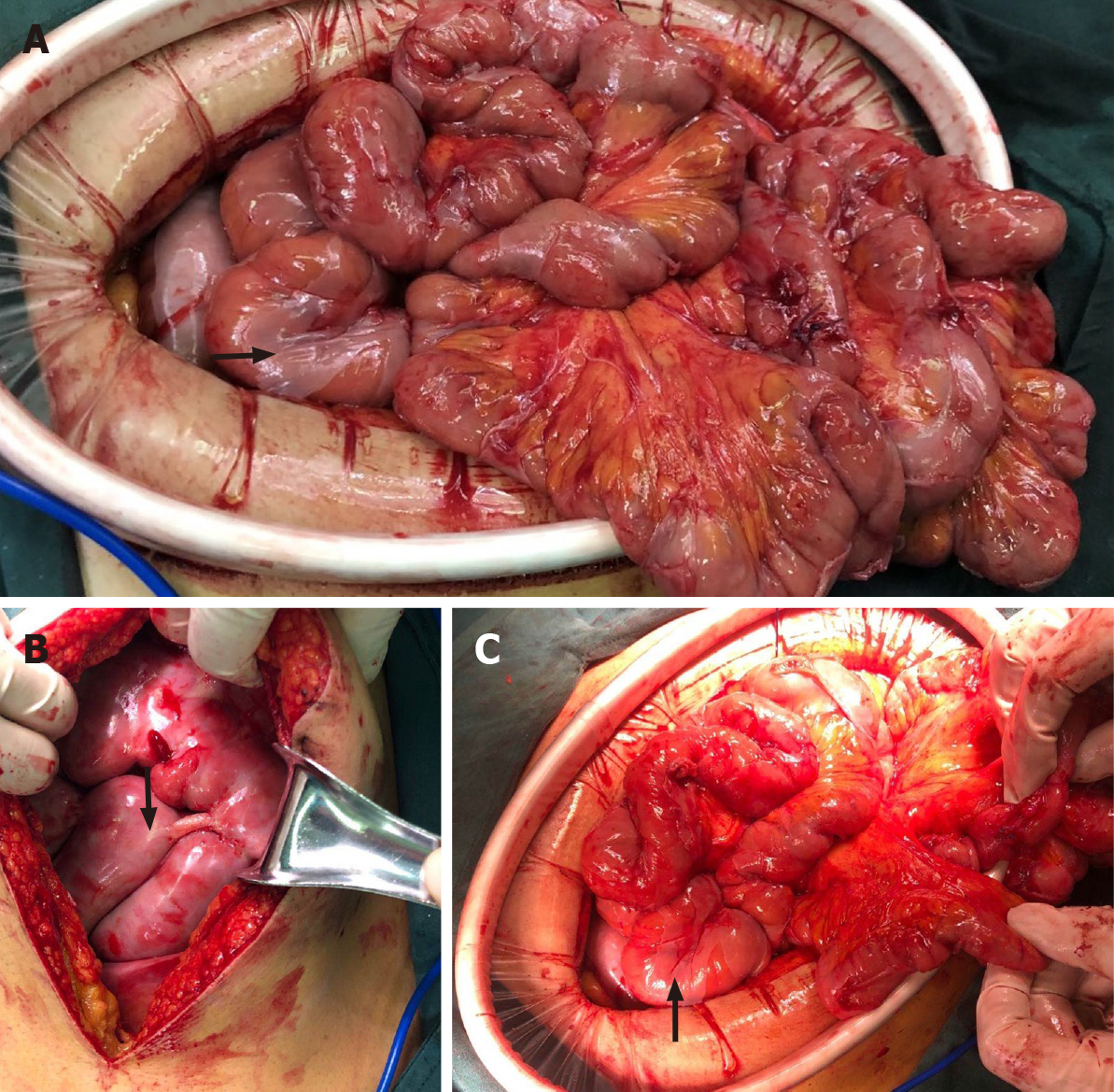

Based on the above findings, the patient was transferred to the general surgery department of our hospital to excise the mass for further diagnosis. Intraoperative findings showed a fibrous membrane encasing the stomach and small intestine (Figure 3). A 3 cm × 3 cm mass with a pedicel was found in the sigmoid colon. Thus, a diagnosis of EPS was made according to the discovery in the operation. Going back to the former MRI and CT images (Figure 1 and 2), we found that the bowel loops were aggregated in a cocoon-like shape encased by a thick membrane (as shown by the arrow).

To relieve symptoms, a gastric tube was inserted and the daily discharge was up to 1000 mL before the surgery. The membrane was dissected and adhesiolysis was done to release the trapped organs. The mass was removed and lateral anastomosis of the colon was performed. The pathological finding of the biopsy was tubular-villous adenoma with high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia. Before and after the surgery, a series of supportive treatments such as parenteral nutrition, gastrointestinal decompression, anti-infection, and hemostatic therapy were taken.

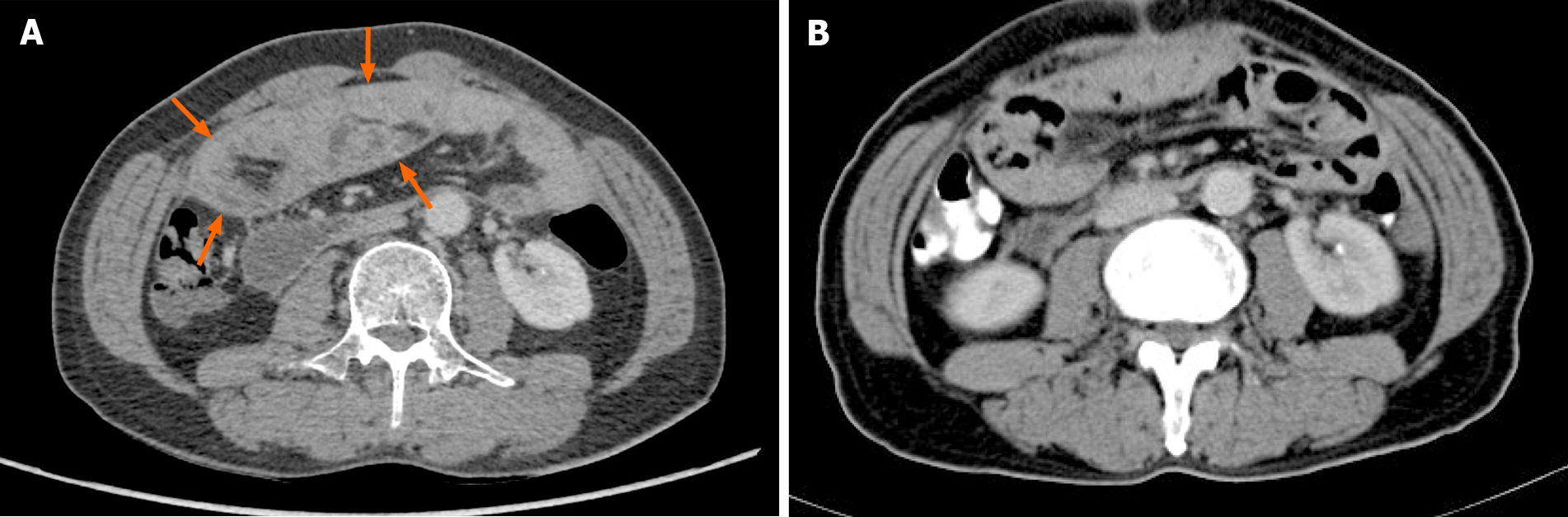

An abdominal CT scan showed no obvious abnormality (Figure 4). Forty-four days after the operation, the patient recovered and was discharged, and there was no recurrence of the disease during a follow-up period of 3 mo.

Although the specific etiology of EPS is still a mystery, there have been many hypotheses proposed in recent years[1-3,6]. It is a general consensus that EPS is classified as primary and secondary. The former mainly includes retrograde menstruation or poor perineal hygiene causing viral or bacterial infection and peritoneal inflammation, which is mostly seen in adolescent girls[7]. Moreover, congenital dysplasia of the greater omentum is also a common cause, which can cover or adhere to intra-abdominal organs such as the stomach and small intestine, leading to the poor peristalsis of the alimentary canal[2,8]. Secondary EPS is more commonly seen in patients with peritoneal irritation or inflammation. It may be triggered by peritoneal dialysis, surgical shunts, abdominal malignancies, alcoholic liver cirrhosis, autoimmune diseases, etc.[1,6,9,10]. The evolution of EPS is a prolonged and chronic course, in which various inciting factors stimulate the expression of proinflammatory and proangiogenic cytokines mediating an inflammatory cascade. As a result, peritoneal mesothelial cells transform into mesenchymal cells and then extracellular matrix and fibrous tissue produce, interweaving to a cocoon[1,3].

There have been several cases indicating that liver cirrhosis is a high-risk factor for EPS. Yamamoto et al[11] reported that two patients with liver cirrhosis, who experienced persistent intraabdominal infection, were diagnosed with EPS. Wakabayashi et al[10] reported a case with perforative peritonitis caused by alcoholic liver cirrhosis was diagnosed with EPS at laparotomy. According to consensus on the diagnosis and management of primary biliary cirrhosis (cholangitis)[12], someone with positive mitochondrial antibody and abnormal biochemical markers of liver cholestasis like ALP can be diagnosed with primary biliary sclerosis. In this case, an autoimmune liver disease test showed that AMA-M2 was positive and ALP exceeded the normal. Therefore, our patient might be diagnosed with cholestatic cirrhosis. In addition, intraabdominal surgery has been reported as one of the implicated triggers[1,13]. Kaman et al[13] reported that a patient with a history of LC was diagnosed with EPS a year later, which was similar to our case. To sum up, the patient was indeed at a higher risk of EPS.

The symptoms and signs of EPS are nonspecific. Generally, patients with EPS present with abdominal pain, abdominal distension, emesis, malnutrition, etc. These symptoms are usually intermittent and recrudescent[1,6]. However, it should be noticed that some patients show sudden acute ileus and even perforation[4]. As many studies reported, the abdomen is inconsistent at palpation, some parts are soft representing dilated bowel loops while some are fixed because of the dense fibrous membrane[5,6]. In this case, the patient developed vomiting and abdominal distension and the frequency of defecation events was drastically reduced or even ceased, which resembled the features of bowel obstruction.

At present, there is no golden standard of imaging to diagnose EPS, but the advances of radiographic technology allow clinicians to make a reliable diagnosis other than laparotomy[6]. “Cauliflower” is a very vivid metaphor for the kinking intestine loops[1]. It is commonly seen that much gas gathers in the small bowel, colon, or rectum. Sometimes, peritoneal calcification and dilation of the bowel with air-fluid levels can be depicted. Compared with ultrasonography or abdominal plain films, CT may be the best imaging technique in the diagnosis of EPS[1,14]. MRI has a similar appearance. In this case, neither obvious calcification nor air-fluid levels were depicted, but much gas gathered in the intestine according to ultrasonography, CT, and abdominal plain films. In fact, a thick membrane encasing the intestine should have been discovered earlier by CT and MRI, but no radiologist attached great importance to this phenomenon because of lack of experience.

With regard to the treatment of EPS, surgery is considered a golden-standard method[1,4,6]. However, whether surgery can be an option for the patient depends on his/her explicit condition. Conservative treatment such as adjusting inappropriate lifestyle is suitable for patients with mild symptoms. Sometimes, nutritional support and application of immuno-suppression are also beneficial to treating EPS[4,15]. In this case, symptomatic support treatment such as parenteral nutrition, antiemetics, and improving gastrointestinal motility did not work. However, laparotomy including enterolysis to free all the small intestine and resection of the lesion located in the sigmoid colon eased the patient’s symptoms. At last, he recovered and was discharged 44 d after the operation.

In conclusion, AMA-M2 is a marker of primary biliary sclerosis and may help to make a preoperative diagnosis of EPS, but it still needs more relevant cases or experiments for further verification.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Itabashi M, Primadhi RA S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Danford CJ, Lin SC, Smith MP, Wolf JL. Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:3101-3111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 2. | Li S, Wang JJ, Hu WX, Zhang MC, Liu XY, Li Y, Cai GF, Liu SL, Yao XQ. Diagnosis and Treatment of 26 Cases of Abdominal Cocoon. World J Surg. 2017;41:1287-1294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wilson RB. Hypoxia, cytokines and stromal recruitment: parallels between pathophysiology of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis, endometriosis and peritoneal metastasis. Pleura Peritoneum. 2018;3:20180103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Li N, Zhu W, Li Y, Gong J, Gu L, Li M, Cao L, Li J. Surgical treatment and perioperative management of idiopathic abdominal cocoon: single-center review of 65 cases. World J Surg. 2014;38:1860-1867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Al-Thani H, El Mabrok J, Al Shaibani N, El-Menyar A. Abdominal cocoon and adhesiolysis: a case report and a literature review. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2013;2013:381950. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Singhal M, Krishna S, Lal A, Narayanasamy S, Bal A, Yadav TD, Kochhar R, Sinha SK, Khandelwal N, Sheikh AM. Encapsulating Peritoneal Sclerosis: The Abdominal Cocoon. Radiographics. 2019;39:62-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Foo KT, Ng KC, Rauff A, Foong WC, Sinniah R. Unusual small intestinal obstruction in adolescent girls: the abdominal cocoon. Br J Surg. 1978;65:427-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Li BB, Yang XH, Wen YH, Tang ZX, Sun D, Qin L, Qian. HX Clinical characteristics and experience for the diagnosis and surgical treatment of abdominal cocoon. Zhonghua Putong Waike Zazhi. 2020;35:468-470. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Nakayama M, Maruyama Y, Numata M. Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis is a separate entity: Con. Perit Dial Int. 2005;25 Suppl 3:S107-S109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wakabayashi H, Okano K, Suzuki Y. Clinical challenges and images in GI. Image 2. Perforative peritonitis on sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis (abdominal cocoon) in a patient with alcoholic liver cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:854, 1210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yamamoto S, Sato Y, Takeishi T, Kobayashi T, Hatakeyama K. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis in two patients with liver cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:172-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chinese Medical Association Hepatology Branch. Consensus on the diagnosis and management of primary biliary cirrhosis (cholangitis). Zhonghua Ganzang Bing Zazhi. 2016;24:5-13. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Kaman L, Iqbal J, Thenozhi S. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis: complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2010;20:253-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Oran E, Seyit H, Besleyici C, Ünsal A, Alış H. Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis as a late complication of peritoneal dialysis. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2015;4:205-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Junor BJ, McMillan MA. Immunosuppression in sclerosing peritonitis. Adv Perit Dial. 1993;9:187-189. [PubMed] |