Published online Jul 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i21.6041

Peer-review started: February 19, 2021

First decision: April 4, 2021

Revised: April 17, 2021

Accepted: May 24, 2021

Article in press: May 24, 2021

Published online: July 26, 2021

Processing time: 129 Days and 15.7 Hours

Academic studies have proved that anti-programmed death-1 (PD-1) monoclonal antibodies demonstrated remarkable activity in relapsed/refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL). However, most patients ultimately experienced failure or resistance. It is urgent and necessary to develop a novel strategy for relapsed/refractory cHL. The aim of this case report is to evaluate the combi

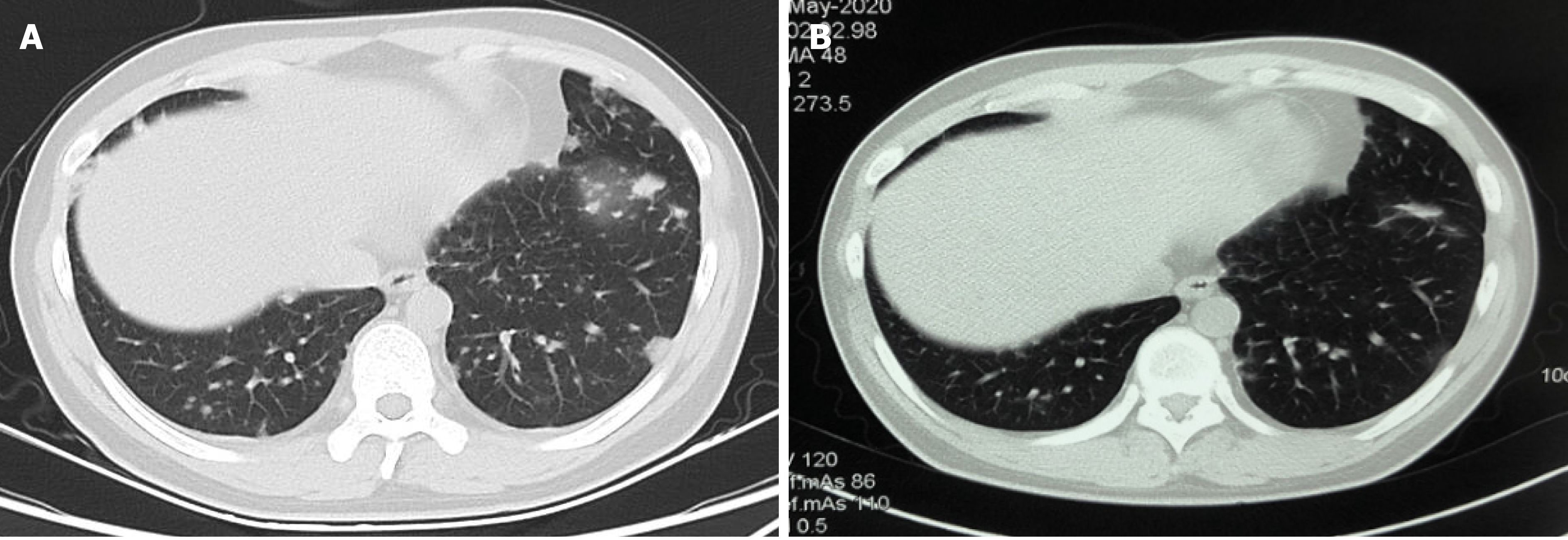

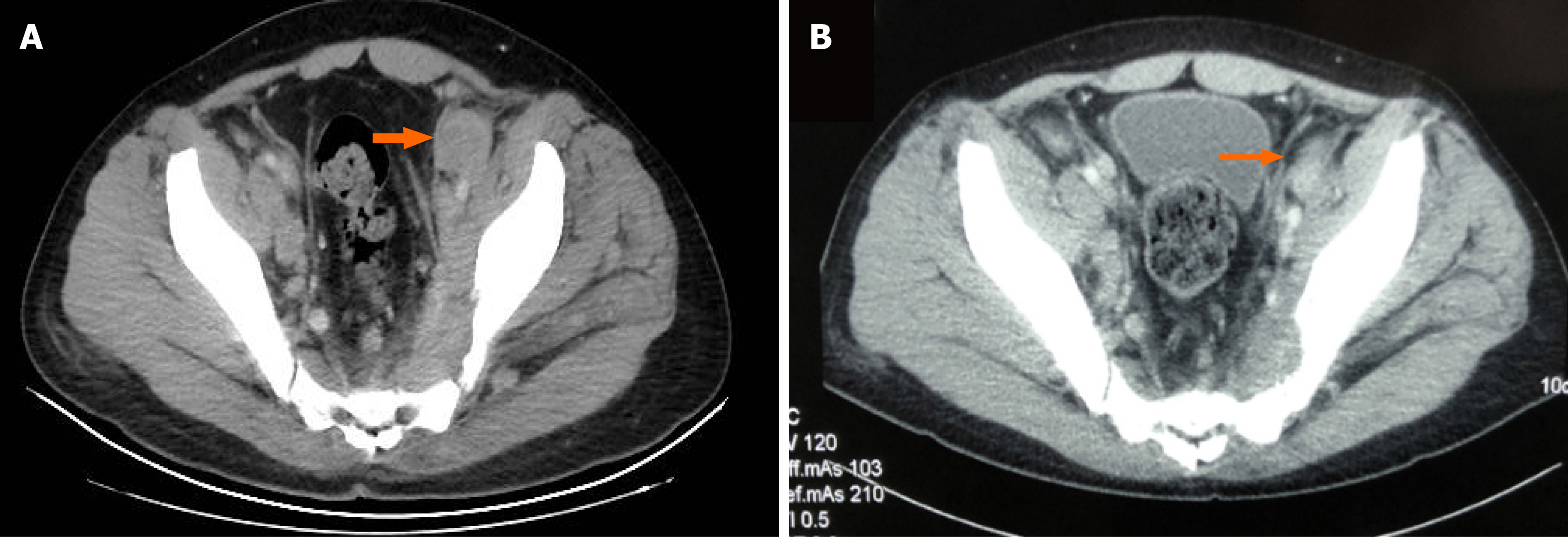

The patient was a 27-year-old man who complained of enlarged right-sided cervical lymph nodes and progressive pain aggravation of the right shoulder over the past 3 mo before admission. Histological analysis of lymph node biopsy was suggestive of cHL. The patient experienced failure of eight lines of therapy, including multiple cycles of chemotherapy, PD-1 blockade, and anti-CD47 antibody therapy. Contrast-enhanced CT showed that the tumors of the chest and abdomen significantly shrunk or disappeared after three cycles of treatment with decitabine plus tislelizumab. The patient had been followed for 11.5 mo until March 2, 2021, and no progressive enlargement of the tumor was observed.

The strategy of combining low-dose decitabine with tislelizumab could reverse the resistance to PD-1 inhibitors in patients with heavily pretreated relapsed/ refractory cHL. The therapeutic effect of this strategy needs to be further assessed.

Core Tip: We report a 27-year-old man who complained of enlarged right-sided cervical lymph nodes and progressive pain aggravation of the right shoulder over the past 3 mo before admission. Histological analysis of lymph node biopsy was suggestive of classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The patient experienced failure of eight lines of therapy. Computed tomography showed that the tumors of the chest and abdomen significantly shrunk or disappeared after three cycles of treatment with low-dose decitabine plus tislelizumab. The patient had been followed for 11.5 mo until March 2, 2021, and no progressive enlargement of the tumor was observed.

- Citation: Ding XS, Mi L, Song YQ, Liu WP, Yu H, Lin NJ, Zhu J. Relapsed/refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma effectively treated with low-dose decitabine plus tislelizumab: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(21): 6041-6048

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i21/6041.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i21.6041

Classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma (cHL) is a largely curable malignancy of the lymphatic system. Patients with newly diagnosed cHL are often treated with empirical combination chemotherapy regimens, such as ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine). Approximately 20% to 30% of patients will experience progression after treatment or fail to respond to induction therapy[1,2]. For these patients, < 20% were exposed to autologous stem-cell transplantation stem-cell transplantation (ASCT) and even fewer to brentuximab vedotin (BV) in China. In recent years, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have provided very impressive results with prolonged remission or disease stabilization in many patients. Unfortunately, the majority of these patients will experience resistance or failure, and subsequent therapy is challenging[3,4]. Recently, clinical data found that resistance to ICIs may be reversed by hypomethylating agents, such as decitabine, in heavily pretreated cHL patients[5,6]. The aim of this case report is to evaluate the combination approach of low-dose decitabine plus a programmed death-1 (PD-1) inhibitor in relapsed/refractory cHL patients with prior PD-1 inhibitor exposure.

The patient was a 27-year-old man who complained of enlarged right-sided cervical lymph nodes and progressive pain aggravation of the right shoulder in 2014.

The patient’s right-sided cervical lymph nodes appeared significantly enlarged approximately 3 mo before admittance, and lymph node biopsy was suggestive of cHL. The patient experienced failure of eight lines of therapy. The treatment procedure is provided in Table 1.

| Time of therapy | Treatment | Best efficacy | PFS (mo) |

| November 2014 | ABVD × 6 cycles | CR | 16 |

| March 2016 | AVD × 1 cycle | Unknown | - |

| September 2016 | AVD × 1 cycle | Unknown | - |

| October 2016 | GVD × 4 cycles | PD | 4.8 |

| October 2017 | GVD × 6 cycles | SD | 8.8 |

| July 2018 | ESHAP × 1 cycle | PD | 0.9 |

| October 2018 | AK105 × 9 cycles | PR | 3.5 |

| July 2019 | IBI188 × 16 wk | SD | 3.6 |

| November 2019 | DICE × 2 cycles | PD | 1.3 |

| February 2020 | F0002-ADC × 1 cycle | PD | 0.6 |

| March 2020 | Decitabine plus tislelizumab | PR | 11.5 |

The patient was diagnosed with subclinical hypothyroidism in September 2018, and levothyroxine (25 µg/d) was prescribed at the Chinese People's Liberation Army General Hospital. The patient’s family history was negative.

Other symptoms were not present and the patient did not drink alcohol, smoke, or have a history of surgery.

On admission, the patient’s blood pressure was 120/74 mmHg, pulse rate was 80 beats/min, and temperature was 36.1 °C. His body weight was 77.5 kg, and his height was 172 cm (BMI 26.2 kg/m2, body surface area). His performance status was 2 according to the criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, and his pain was 6 out of 10 according to the numeric rating scale (NRS). No superficial lymphadenopathy was noted. The left buttock was fuller than the right buttock, and no soft tissue tumor was palpated in the left buttock. Left hip tenderness was noted.

On admission, routine blood tests revealed significant leukocytosis, moderate anemia, decreased albumin, and slightly elevated blood urea nitrogen. The patient’s blood biochemical tests were indicative of impaired liver function with a slight elevation of alkaline phosphatase and glutamyl transferase levels. The coagulation function test showed a marked elevation in plasma fibrinogen and activated partial thromboplastin time levels. The results are presented in Table 2.

| Result | Normal range | |

| Hematology | ||

| White blood cell count | 20.81 × 109/L | 4.0-10.0 |

| Red blood cell count | 3.17 × 1012/L | 3.5-5.5 |

| Hemoglobin | 87 g/L | 120.0-160.0 |

| Hematocrit | 28.8% | 37.0-49.0 |

| MCV | 91 fl | 82.0-92.0 |

| MCH | 27.3 pg | 27.0-31.0 |

| MCHC | 300 g/L | 320.0-360.0 |

| Platelets | 384 × 109/L | 100.0-350.0 |

| Lymphocytes | 0.96 × 109/L | 1.0-5.0 |

| Monocytes | 0.24 × 109/L | 0.2-0.8 |

| Neutrophils | 19.59 × 109/L | 2.0-8.0 |

| Eosinophils | 0 × 109/L | 0.1-0.5 |

| Basophils | 0.02 × 109/L | 0.0-0.1 |

| ESR | ||

| Coagulation | ||

| APTT | 59.3 s | 24.0-39.0 |

| Thrombin time | 16.6 s | 14.0-21.0 |

| Prothrombin time | 12.6 s | 11.0-14.0 |

| INR | 1.11 | 0.8-1.5 |

| Prothrombin activity | 81.9% | 70.0-130.0 |

| Fibrinogen | 942.1 mg/dL | 200.0-400.0 |

| Biochemistry | ||

| C-reactive protein | 106.3 mg/L | < 8.0 |

| Procalcitonin | 0.47 ng/mL | < 0.5 |

| Glucose | 7.24 mmol/L | 3.6-6.1 |

| Creatinine | 57 µmol/L | 50.0-130.0 |

| MDRD GFR | > 60 mL/min | > 60 |

| Uric acid | 318 µmol/L | 90.0-420.0 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | 260 IU/L | 110.0-240.0 |

| ALB | 40.1 g/L | 35.0-55.0 |

| TP | 69.4 g/L | 60.0-80.0 |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 178 IU/L | 40.0-160.0 |

| Serum iron | 9.9 µmol/L | 10.6-28.3 |

| Serum ferritin | 7585 µg/L | 30.0-400.0 |

| UIBC | 20 µmol/L | 19.7-66.2 |

| TIBC | 29.9 µmol/L | 40.8-76.6 |

| Total cholesterol | 4.66 mmol/L | 2.84-5.68 |

| Triglycerides | 0.97 mmol/L | 0.56-1.7 |

| Hormones | ||

| TSH | 3.47 mIU/L | 0.27-4.2 |

| FT3 | 3.59 pmol/L | 3.1-6.8 |

| FT4 | 17.34 pmol/L | 12.0-22.0 |

| Electrolytes | ||

| Sodium | 137 mmol/L | 135.0-145.0 |

| Potassium | 4.47 mmol/L | 3.5-5.3 |

| Calcium-total | 2.35 mmol/L | 2.12-2.75 |

| Phosphates inorganic | 0.83 mmol/L | 0.69-1.6 |

| Liver enzymes | ||

| ALT | 25 IU/L | 0.0-40.0 |

| AST | 23 IU/L | 0.0-45.0 |

| GGT | 151 IU/L | 10.0-50.0 |

| DBIL | 3.0 µmol/L | 0.0-6.0 |

| Total bilirubin | 9.4 µmol/L | 1.7-20.0 |

| Virology tests | ||

| Anti-HCV | Negative | |

| HbsAg | Negative | |

| Anti-HIV | Negative | |

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest revealed that multiple lung nodules significantly decreased or disappeared after treatment with three cycles of combination therapy of decitabine and tislelizumab (Figure 1). Similarly, a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed that abdominal lymph nodes decreased in size (Figure 2).

The patient was finally diagnosed with cHL by biopsy of the right cervical lymph node. The subtype was nodular sclerosis, Ann Arbor stage IVB, involving the left iliac muscle, left piriformis muscle, sacrum, bilateral ilium, bone marrow, left supraclavicular lymph nodes, mediastinal lymph nodes, right hilar lymph nodes, retroperitoneal lymph nodes, and bilateral lymph nodes near iliac blood vessels. Immunohistochemistry revealed the following: CD15 (+), CD163 (-), CD3 (-), CD30 (+), EBER (-), EBV (-), EMA (-), Ki67 (+), LCA (-), PAX-5 (weakly +), CD20 (+), CD57 (-), ALK (-), and CD68 (-).

The patient was treated with decitabine (10 mg/d, days 1 to 5) plus tislelizumab (200 mg, day 6) every 3 wk. A total of 12 courses of combination therapy were delivered.

To date, the patient has completed 12 cycles of decitabine in combination with the PD-1 inhibitor tislelizumab, and the date of the last cycle was November 17, 2020. Abdominal pain was significantly alleviated, and the NRS score decreased to 1 to date. Partial remission was achieved after treatment until March 2, 2021, and progression-free survival was 11.5 mo. The treatment was safe and well tolerated.

It is difficult to treat relapsed/refractory cHL patients with a heavy pretreatment history due to the lack of standard treatment options. PD-1 inhibitor is considered as a promising option. Programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1)/PD-L2 protein is often upregulated in Hodgkin lymphoma cells due to frequent copy-number gains of CD274 (PD-L1) and PDC1LG2 (PD-L2) on chromosome 9p24.1 and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection, which binds the PD-1 receptor on T cells, inducing T-cell exhaustion through the inhibition of T-cell activation and proliferation[4]. In patients with relapsed/ refractory cHL who experienced failure with both ASCT and BV, PD-1 blockade has an objective response rate of 65% to 87%[7,8]. However, most patients will ultimately experience progression with a median progression-free survival (PFS) of approximately 12 mo. Thus, an unmet medical need for effective therapies in patients who experienced failure with PD-1 blockade therapy remains.

Recently, a close association between epigenetic aberrations and immune escape has been explored in cHL. Ghoneim et al[9] reported that de novo DNA methylation programming is causal in reinforcing the development of T-cell exhaustion and establishes a stable cell-intrinsic barrier to PD-1 blockade, causing a decrease in the efficacy of anti-PD-1 antibodies, whereas methylation inhibition could enhance the antitumor activity of PD-1 blockade-mediated T-cell rejuvenation. Falchi et al[5] published their experience on a few patients with relapsed/refractory cHL, suggesting that treatment with a PD-1 inhibitor might result in higher complete remission rates as observed in 5/5 patients who were previously exposed to 5-azacitidine. A similar clinical conclusion was obtained by a single-center, two-arm, open-label phase II trial, which included 86 patients with relapsed/refractory cHL after failure of a median of four lines of therapy. In total, 25/86 had been previously exposed to PD-1 inhibitors, and nivolumab was the most commonly used drug, accounting for 72% of cases[6]. The PD-1 inhibitor used in this trial was camrelizumab, and the hypomethylating agent was decitabine, which has been approved to treat myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemia in the United States. The 25 patients with prior PD-1 inhibitor exposure were treated with a combination of 10 mg/d decitabine on days 1-5 and 200 mg camrelizumab on day 8 every 3 wk, and the objective response rate (ORR) and complete remission rate were 52% and 28%, respectively. The ORR was higher in patients with acquired resistance to PD-1 blockade compared to patients with primary resistance (62% vs 42%). At one year, the PFS and duration of response rates were 59% and 81%, respectively. Combination therapy could potentially reverse PD-1 resistance due to low-dose decitabine changing the epigenetic status of both tumors and immunocytes, increasing the infiltration of both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, boosting T-cell function, enhancing tumor immunogenicity, and synergizing with anti-PD-1 antibodies to restore immunosurveillance[10-12]. Thus, hypomethylating agents might have a suppressive effect on tumoral immune escape in relapsed/refractory cHL. Another explanation for the reversal of PD-1 resistance may be attributed to the difference in the structure of different anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibodies. Anti-PD-1 Abs, including pembrolizumab, nivolumab, and other anti-PD-1s, all harbor wild-type Fc regions in the antibody structure. Binding to FcγR on macrophages compromises the antitumor activity of PD-1 monoclonal antibodies with the wild-type Fc region through activation of antibody-dependent macrophage-mediated killing of T effector cells[13,14]. Tislelizumab is a humanized IgG4 anti–PD-1 antibody specifically engineered to minimize binding to FcγR on macrophages. Preclinical data showed that in macrophage- and T cell-enriched conditions, tislelizumab did not induce antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis; thus, its antitumor activity was not compromised[15].

Here, we report the case of a relapsed/refractory cHL patient who experienced failure with eight lines of therapy and was treated with a combination of low-dose decitabine plus tislelizumab and demonstrate that this combination approach is effective and safe. Further studies are needed to assess the therapeutic effect of this combination therapy in a larger cohort of patients with relapsed/refractory cHL.

The strategy of combining low-dose decitabine with tislelizumab could reverse the resistance to PD-1 inhibitors in patients with heavily pretreated relapsed/refractory cHL.

The authors thank the patient who participated in this study and his family.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Yikilmaz AS S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Armitage JO. Early-stage Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:653-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kuruvilla J, Keating A, Crump M. How I treat relapsed and refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2011;117:4208-4217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Younes A, Santoro A, Shipp M, Zinzani PL, Timmerman JM, Ansell S, Armand P, Fanale M, Ratanatharathorn V, Kuruvilla J, Cohen JB, Collins G, Savage KJ, Trneny M, Kato K, Farsaci B, Parker SM, Rodig S, Roemer MG, Ligon AH, Engert A. Nivolumab for classical Hodgkin's lymphoma after failure of both autologous stem-cell transplantation and brentuximab vedotin: a multicentre, multicohort, single-arm phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1283-1294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 664] [Cited by in RCA: 734] [Article Influence: 81.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Roemer MG, Advani RH, Ligon AH, Natkunam Y, Redd RA, Homer H, Connelly CF, Sun HH, Daadi SE, Freeman GJ, Armand P, Chapuy B, de Jong D, Hoppe RT, Neuberg DS, Rodig SJ, Shipp MA. PD-L1 and PD-L2 Genetic Alterations Define Classical Hodgkin Lymphoma and Predict Outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2690-2697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 500] [Cited by in RCA: 608] [Article Influence: 67.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Falchi L, Sawas A, Deng C, Amengual JE, Colbourn DS, Lichtenstein EA, Khan KA, Schwartz LH, O'Connor OA. High rate of complete responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma previously exposed to epigenetic therapy. J Hematol Oncol. 2016;9:132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nie J, Wang C, Liu Y, Yang Q, Mei Q, Dong L, Li X, Liu J, Ku W, Zhang Y, Chen M, An X, Shi L, Brock MV, Bai J, Han W. Addition of Low-Dose Decitabine to Anti-PD-1 Antibody Camrelizumab in Relapsed/Refractory Classical Hodgkin Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:1479-1489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 25.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ansell SM, Lesokhin AM, Borrello I, Halwani A, Scott EC, Gutierrez M, Schuster SJ, Millenson MM, Cattry D, Freeman GJ, Rodig SJ, Chapuy B, Ligon AH, Zhu L, Grosso JF, Kim SY, Timmerman JM, Shipp MA, Armand P. PD-1 blockade with nivolumab in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:311-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2598] [Cited by in RCA: 2798] [Article Influence: 279.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chen R, Zinzani PL, Fanale MA, Armand P, Johnson NA, Brice P, Radford J, Ribrag V, Molin D, Vassilakopoulos TP, Tomita A, von Tresckow B, Shipp MA, Zhang Y, Ricart AD, Balakumaran A, Moskowitz CH; KEYNOTE-087. Phase II Study of the Efficacy and Safety of Pembrolizumab for Relapsed/Refractory Classic Hodgkin Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2125-2132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 659] [Cited by in RCA: 754] [Article Influence: 94.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ghoneim HE, Fan Y, Moustaki A, Abdelsamed HA, Dash P, Dogra P, Carter R, Awad W, Neale G, Thomas PG, Youngblood B. De Novo Epigenetic Programs Inhibit PD-1 Blockade-Mediated T Cell Rejuvenation. Cell 2017; 170: 142-157. e19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 386] [Cited by in RCA: 575] [Article Influence: 71.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nie J, Zhang Y, Li X, Chen M, Liu C, Han W. DNA demethylating agent decitabine broadens the peripheral T cell receptor repertoire. Oncotarget. 2016;7:37882-37892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Li X, Zhang Y, Chen M, Mei Q, Liu Y, Feng K, Jia H, Dong L, Shi L, Liu L, Nie J, Han W. Increased IFNγ+ T Cells Are Responsible for the Clinical Responses of Low-Dose DNA-Demethylating Agent Decitabine Antitumor Therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:6031-6043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mei Q, Chen M, Lu X, Li X, Duan F, Wang M, Luo G, Han W. An open-label, single-arm, phase I/II study of lower-dose decitabine based therapy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6:16698-16711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Dahan R, Sega E, Engelhardt J, Selby M, Korman AJ, Ravetch JV. FcγRs Modulate the Anti-tumor Activity of Antibodies Targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 Axis. Cancer Cell. 2015;28:285-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in RCA: 290] [Article Influence: 29.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Arlauckas SP, Garris CS, Kohler RH, Kitaoka M, Cuccarese MF, Yang KS, Miller MA, Carlson JC, Freeman GJ, Anthony RM, Weissleder R, Pittet MJ. In vivo imaging reveals a tumor-associated macrophage-mediated resistance pathway in anti-PD-1 therapy. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 340] [Cited by in RCA: 495] [Article Influence: 70.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zhang T, Song X, Xu L, Ma J, Zhang Y, Gong W, Zhou X, Wang Z, Wang Y, Shi Y, Bai H, Liu N, Yang X, Cui X, Cao Y, Liu Q, Song J, Li Y, Tang Z, Guo M, Wang L, Li K. The binding of an anti-PD-1 antibody to FcγRΙ has a profound impact on its biological functions. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2018;67:1079-1090. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 29.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |