Published online Jul 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i21.5972

Peer-review started: January 5, 2021

First decision: April 29, 2021

Revised: May 11, 2021

Accepted: May 26, 2021

Article in press: May 26, 2021

Published online: July 26, 2021

Processing time: 197 Days and 17.7 Hours

Meigs syndrome is a rare neoplastic disease characterized by the triad of benign solid ovarian tumor, ascites, and pleural effusion. In postmenopausal women with pleural effusions, ascites, elevated CA-125 level, and pelvic masses, the probability of disseminated disease is high. Nevertheless, the final diagnosis is based on its histopathologic features following surgical removal of a mass lesion. Here we describe a case of Meigs syndrome with pleural effusion as the initial manifestation.

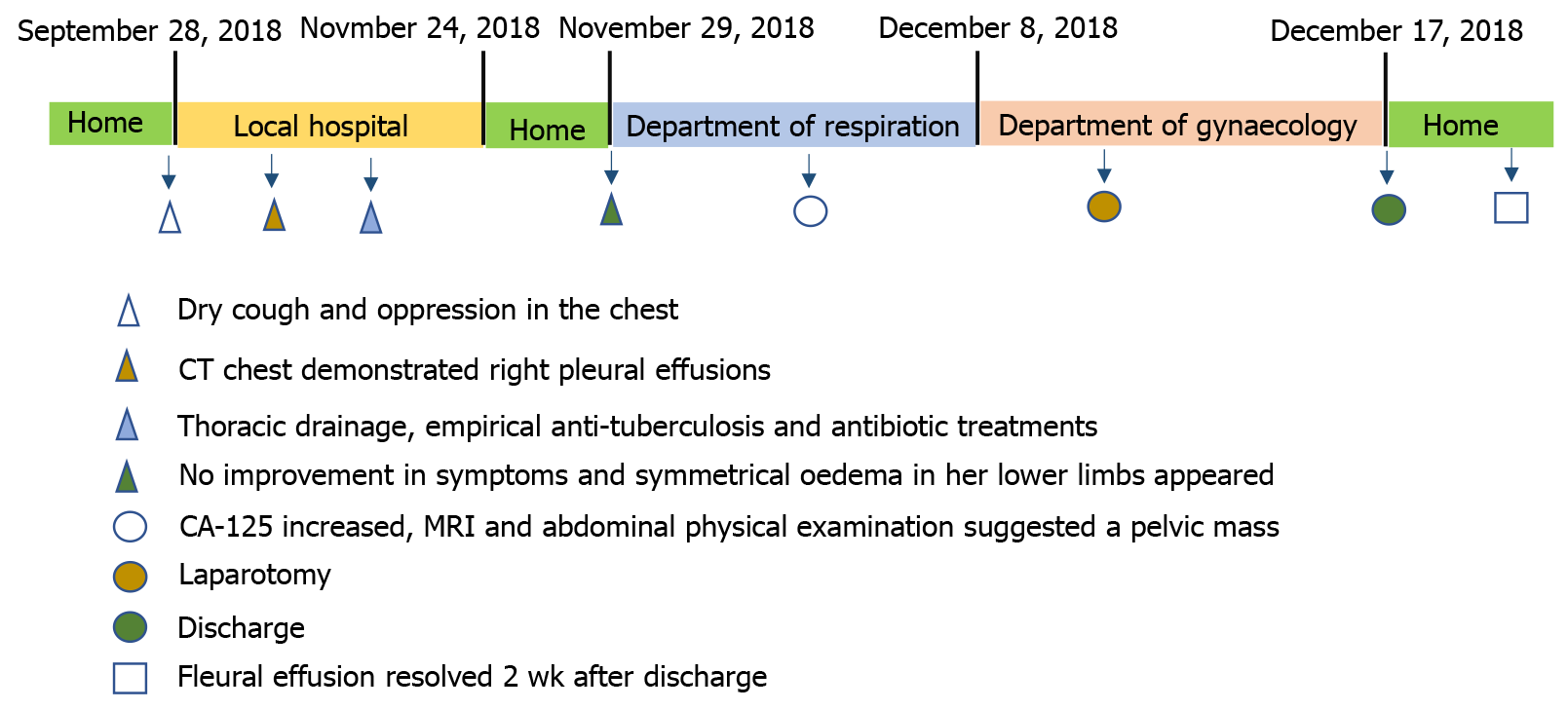

A 52-year-old woman presented with a 2-mo history of dry cough and oppression in the chest and was admitted to our hospital due to recurrent pleural effusion and gradual worsening of dyspnea that had occurred over the previous month. Two months before admission, the patient underwent repeated chest drainage and empirical anti-tuberculosis treatment. However, the pleural fluid accumulation persisted, and the patient began to experience dyspnea on exertion leading to admission. A computed tomography scan of the chest, abdominal ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging confirmed the presence of right-sided pleural effusion and ascites with a right ovarian mass. Serum tumor markers showed raised CA-125. With a suspicion of a malignant tumor, the patient underwent laparoscopic excision of the ovarian mass and the final pathology was consistent with an ovarian fibrothecoma. On the seventh day postoperation, the patient had resolution of the right-sided pleural effusion.

Despite the relatively high risk of malignancy when an ovarian mass associated with hydrothorax is found in a patient with elevated serum levels of CA-125, clinicians should be aware about rare benign syndromes, like Meigs, for which surgery remains the preferred treatment.

Core Tip: This case highlights the difficulties that may be encountered in the management of patients with Meigs syndrome, including potential misdiagnosis of tuberculosis or malignant diseases that may influence the medical and surgical approach. Although initial suspicions of malignancy in patients with undiagnosed pleural effusion and elevated CA-125 level, Meigs syndrome should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

- Citation: Hou YY, Peng L, Zhou M. Meigs syndrome with pleural effusion as initial manifestation: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(21): 5972-5979

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i21/5972.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i21.5972

Meigs syndrome is an extremely rare gynaecological disease, presenting as fibroma or a fibroma-like tumor (thecoma, granulosa cell tumor, or Brenner tumor) accompanied by ascites and hydrothorax that rapidly resolve after removal of the tumor[1]. For some patients, pleural effusion, which is relatively easy to detect clinically, is often the first manifestation of Meigs syndrome. However, these patients are often initially misdiagnosed with tuberculosis or malignant diseases, as a consequence a delay in necessary treatment occurs. Here, we present a case of classic Meigs syndrome with pleural effusion as the first manifestation, which had been misdiagnosed at an early stage.

On November 29, 2018, a 52-year-old woman was referred to our hospital with symptoms of dry cough and oppression in the chest. She had no other physical complaints.

The patient’s symptoms started 2 mo prior to the admission.

The patient’s past medical history included mellitus for 6 mo, hypertension, and laser ablation of vaginal polyps 12 years previously.

General examination of the patient revealed a body temperature of 36.4 °C, pulse rate of 112 bpm, blood pressure of 112/76 mmHg, respiratory rate of 20 per minute, and oxygen saturation of 94% in room air, which improved to 98% on 3 L/min supplemental oxygen administered intranasally. Auscultation of the chest revealed decreased breath sounds over the right lung field. During the abdominal physical examination, we found a palpable mass in the lower abdomen.

The patient’s hematology, biochemistry, and urinalysis results were all unremarkable. T-spots were negative. However, tests for tumor markers showed an increased cancer antigen-125 level (CA-125, serum 663.3 U/mL and pleural effusion > 1000 U/mL, normal value < 35 U/mL). The serum levels of α-fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen, and other tumor markers were all within normal limits.

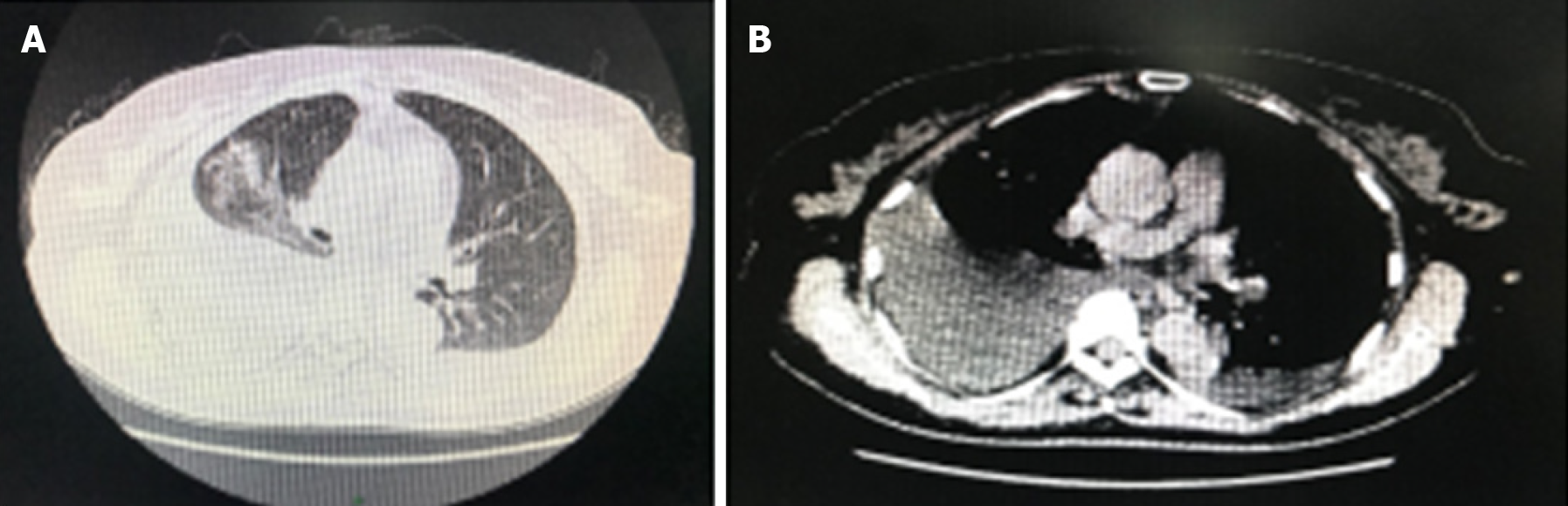

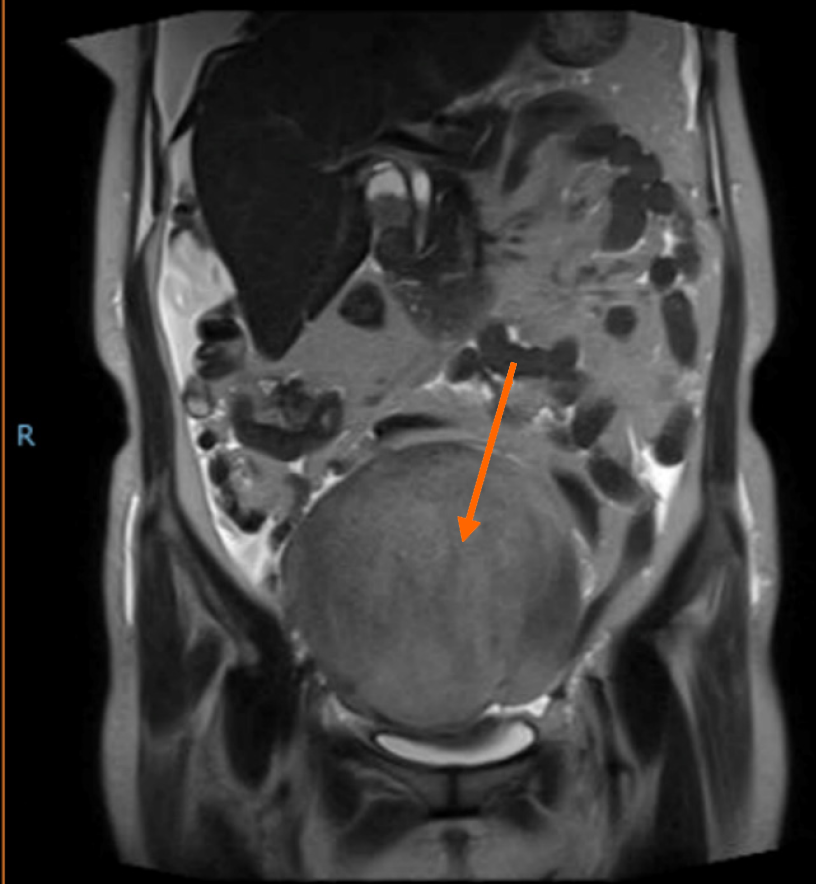

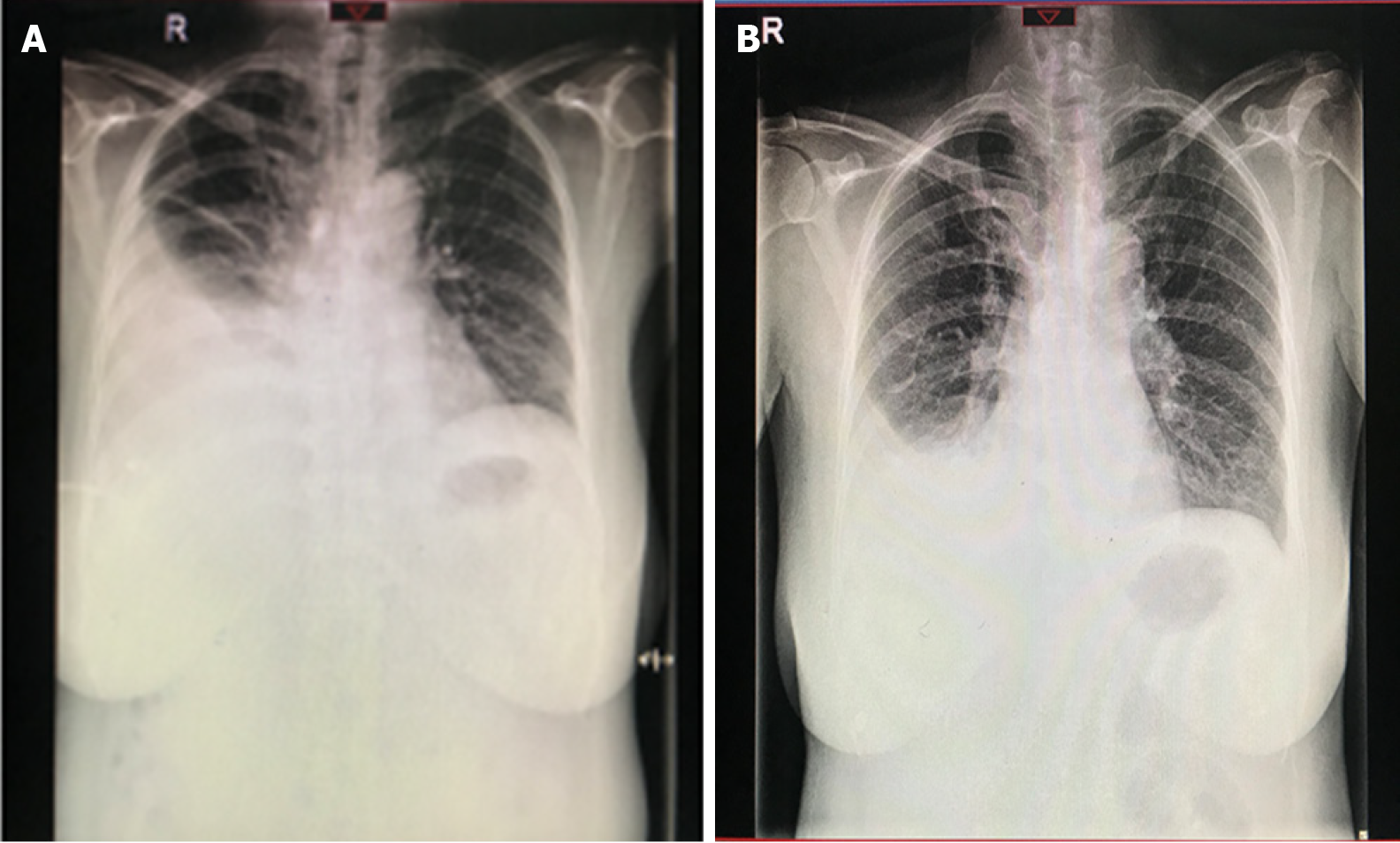

Imaging of the chest by computed tomography demonstrated right pleural effusions. The chest radiography results are shown in Figure 1. Ascites and a large irregular, cystsolidmixed mass (14 mm × 13 mm × 13 mm) in the right ovary were confirmed by abdominal ultrasound examination. Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging revealed a large pelvic mass with a low signal intensity on T1 sequences and a slightly high signal intensity on T2 sequences (Figure 2). Painless gastroscopy was also carried out, but no obvious abnormalities was observed.

Fluid cytology was negative, and histopathologic examination of a pleural biopsy indicated fibrous tissue, striated muscle tissue, adipose tissue, and a few mesenchymal cells at the edge. Thoracic drainage (up to 800 mL/d) was performed several times, and empirical antibiotic therapy and anti-tuberculosis treatment were also initiated at the local hospital (Wuhu 238300, Anhui Province, China). Despite these treatments, symptoms and chest radiographic findings were not improved, and the patient later exhibited symmetrical oedema in the lower limbs. To alleviate her symptoms, thoracic pleural drainage was performed under local anaesthesia on November 30, 2018. The patient’s pleural effusion test results and data of the serum parameters are shown in Table 1. Pleural fluid was consistent with transudative pleural effusion based on Light’s criteria[2]. Samples of pleural fluid were negative on mycobacterial culture, and cytological examination revealed abundant lymphocytes without evidence of malignant cells.

| Variable | Pleural fluid | Blood |

| Appearance | Clear and yellow colored | - |

| White blood cell count | 300 × 106/L | 10.05 × 109/L |

| Total cell count | 400 × 106/L | - |

| Monocytes | 90% | 86.10% |

| Total protein level | 25.50 g/L | 52.70 g/L |

| LDH | 81 U/L | 193 U/L |

| CEA | 1.30 μg/L | 1.50 μg/L |

| CA-125 | > 1000 U/mL | 663.30 U/mL |

| Rivalta test | Negative | - |

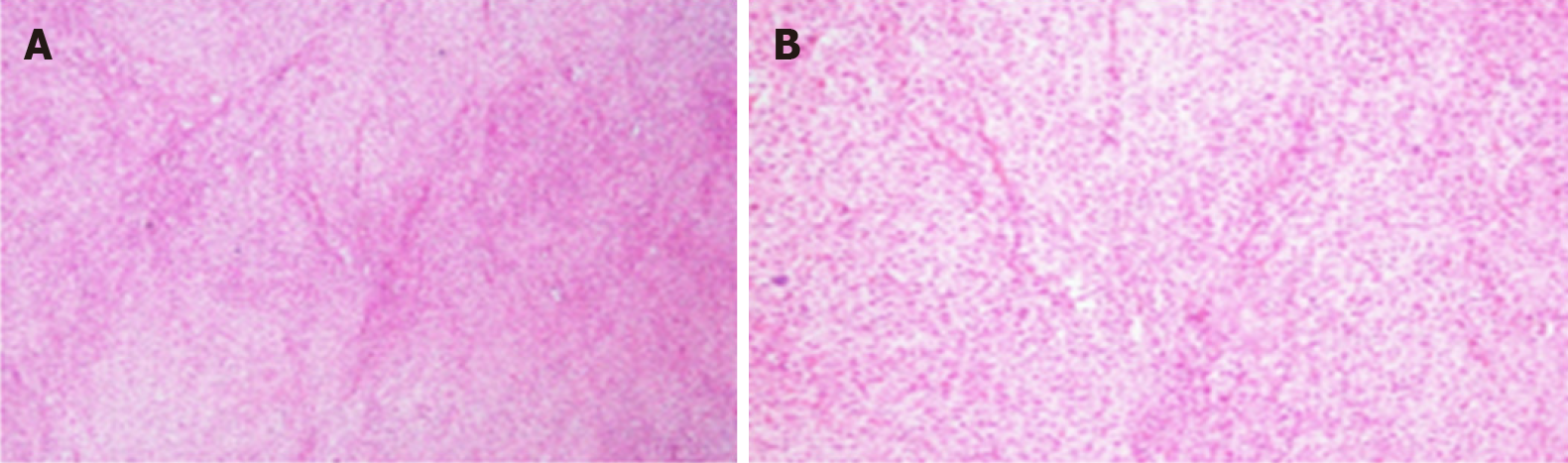

In this case involving a postmenopausal woman with massive pleural effusion and ascites, the possibility of a malignant tumor was initially suspected due to the detection of a pelvic mass and markedly increased CA-125 levels. Therefore, she was referred to the department of gynaecology of our hospital for laparotomy following the advice of gynecologists on December 8, 2018. Intraoperative examination revealed a 13.0 cm × 15.0 cm mixed (solid-cystic) tumor without papillary projection originating from the right ovary. Left ovary atrophy was observed, and no gross abnormalities were observed on the surface of the two fallopian tubes and on the uterus, liver, gallbladder, stomach, or diaphragm. There was no evidence of metastatic lesions. The right tube and ovary were removed for rapid frozen section and it was suggestive of a benign ovarian thecoma. Routine pathological examination after surgery confirmed the right ovarian thecoma (Figure 3). Sections of uterus, bilateral fallopian tube, and left ovary were histologically unremarkable.

The final diagnosis of the presented case was right ovarian thecoma presenting with Meigs syndrome.

The patient and her family members insisted on a hysterectomy and left salpingooophorectomy, which were performed.

The recovery was uneventful, and the patient was discharged from the hospital 7 d after the surgery with a small pleural effusion (Figure 4) which resolved approximately 2 wk after discharge (Figure 5). At the 12-wk followup, the patient recovered well and was asymptomatic, with no evidence of disease on physical examination and normal CA-125 levels (6.0 U/mL).

Meigs syndrome is diagnosed with the discovery of the triad of ascites, pleural effusion, and an ovarian tumor, which is usually benign, occurring together[3]. Historically, in 1866, Spiegelberg et al [4] initially reported the case of a patient with a pelvic mass, pleural effusion, and ascites for which histological examination confirmed the diagnosis of fibroma of the ovary. However, they did not know that removal of the tumor might have cured the patient. In 1887, Demons described a syndrome based on nine patients with benign ovarian cysts who were cured of their ascites and pleural effusion by removal of the cyst[4]. However, this syndrome was not named until 1937 when Joe Vincent Meigs along with Cass published a series of seven patients presenting with a triad of findings: Ascites, hydrothorax, and fibroma of the ovary characterized by the resolution of symptoms with ablation of the tumor[3]. In typical Meigs syndrome, three major criteria must be fulfilled: (1) The existence of benign fibroma or a fibroma-like (thecoma, granulosa cell tumor, or Brenner tumor) ovarian tumor; (2) The presence of ascites and pleural effusion; and (3) Resolution of the ascites and pleural effusion following removal of the ovarian tumors[1,5]. In contrast, pseudo-Meigs syndrome is used to describe similar clinical manifestations characterized by ascites and/or hydrothorax along with malignant or benign ovarian tumors—other than fibromas or fibroma-like tumors—or uterine or fallopian tumors[6].

Currently, surgical resection is still considered to be the only effective curative treatment, and the final diagnosis is dependent on histopathological examination. The prognosis following surgical excision of the tumor is excellent and similar to that of benign tumors[7].

At present, the etiology of ascites and pleural effusion in Meigs syndrome is subject to debate and largely remains to be elucidated. There are several hypotheses regarding the mechanism underlying the generation of peritoneal fluid. It probably occurs by means of a transudative mechanism through the surface of the tumor that exceeds the resorptive capacity of the peritoneum[8]. Other potential explanations include hormone stimulation, obstruction of lymphatic flow by the tumor, and release of inflammatory cytokines and growth factors by tumor cells. The direct cause of pleural fluid formation is thought to involve translocation of ascites to the thoracic cavity via diaphragmatic pores[9]. Pleural effusion is usually bilateral, but in patients with Meigs syndrome, it is usually unilateral with a predominance on the right side due to the larger diameter of transdiaphragmatic lymphatic channels on the right side[10]. Pleural effusion can result from a number of conditions in clinical practice and is mostly associated with malignancy and tuberculosis. Other common causes include congestive cardiac failure, pleural infection, liver cirrhosis, and kidney disease[11]. Due to the substantial variety of originating causes, the differential diagnosis of pleural effusion poses a difficult challenge for clinicians.

Carcinoma antigen-125 (also known as carbohydrate antigen-125 or CA-125), commonly used as a tumor marker, is a strong independent prognostic factor for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer[12-14]. Despite the sensitivity of CA-125 in the detection of ovarian cancer, its specificity is known to be suboptimal. Many other conditions (neoplastic or non-neoplastic) can also cause an elevation of CA-125 levels, including endometriosis, cirrhosis, uterine fibroids, pregnancy, ovarian cysts, and pelvic inflammatory disease[15]. Changes in CA-125 levels during the menstrual cycle have also been reported[16]. Notably, the exact mechanisms that lead to CA-125 elevation in patients with Meigs syndrome remain unclear. Some studies have shown that mesothelial cells from ascites in patients with Meigs syndrome are able to synthesize CA-125. Moreover, ascites volume is positively associated with the expression level of CA-125 but not linearly associated with tumor dimension[17].

As dyspnea (due to large-volume pleural effusion) is a common presenting symptom, a significant proportion of patients might be initially referred to chest physicians. Moreover, Meigs syndrome is rare in clinical practice, and patients with Meigs syndrome can present with pleural effusion as the initial manifestation. For that reason, the differential diagnosis of the cause of pleural effusion is often challenging, and it might be easily misdiagnosed as tuberculosis or malignancy. For respiratory physicians, in patients with pleural effusion of undetermined etiology, other diseases such as gynecological diseases should be considered in the differential diagnosis. As in our case report, pleural effusion generally suggests an underlying disease process that may even be of extrapulmonary origin. Therefore, experimental treatment such as antituberculosis treatment must not be performed blindly. In addition, the presence of a solid mass, ascites, and elevated CA-125 levels does not necessarily indicate advanced malignant disease considering the limited value of CA-125 in differentiating benign from malignant tumors. Benign diseases, such as Meigs syndrome, should also be included in the differential diagnosis. In clinical practice, misdiagnosis and underdiagnosis in patients with Meigs syndrome can pose a serious threat to patient safety and lead to delayed diagnosis and treatment, which are associated with higher mortality rates, so often there is no time to delay.

Meigs syndrome is a rare but important clinical entity to consider in the differential diagnosis in female patients with pleural effusion. The timely and accurate diagnosis and management allow patients to benefit from symptom-relieving treatment to maximize their quality of life. Despite the relatively high risk of malignancy when an ovarian mass associated with hydrothorax is found in a patient with elevated serum levels of CA-125, clinicians should be aware about rare benign syndromes, like Meigs, for which surgery remains the preferred treatment.

We greatly appreciate the patient and the medical staff involved in this study.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Li S, Nocito AL S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | MEIGS JV. Fibroma of the ovary with ascites and hydrothorax; Meigs' syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1954;67:962-985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Light RW, Macgregor MI, Luchsinger PC, Ball WC Jr. Pleural effusions: the diagnostic separation of transudates and exudates. Ann Intern Med. 1972;77:507-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1087] [Cited by in RCA: 1044] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lurie S. Meigs' syndrome: the history of the eponym. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2000;92:199-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Brun JL. Demons syndrome revisited: a review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;105:796-800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | MEIGS JV. Pelvic tumors other than fibromas of the ovary with ascites and hydrothorax. Obstet Gynecol. 1954;3:471-486. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Hardy E. Meigs' syndrome and pseudo-Meigs' syndrome. J R Soc Med. 1987;80:537. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Shen Y, Liang Y, Cheng X, Lu W, Xie X, Wan X. Ovarian fibroma/fibrothecoma with elevated serum CA125 level: A cohort of 66 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e11926. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Samanth KK, Black WC 3rd. Benign ovarian stromal tumors associated with free peritoneal fluid. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1970;107:538-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Amant F, Gabriel C, Timmerman D, Vergote I. Pseudo-Meigs' syndrome caused by a hydropic degenerating uterine leiomyoma with elevated CA 125. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;83:153-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Krenke R, Maskey-Warzechowska M, Korczynski P, Zielinska-Krawczyk M, Klimiuk J, Chazan R, Light RW. Pleural Effusion in Meigs' Syndrome-Transudate or Exudate? Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e2114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hung TH, Tseng CW, Tsai CC, Tseng KC, Hsieh YH. The long-term outcomes of cirrhotic patients with pleural effusion. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:46-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Moon JH, Lee HJ, Kang WD, Kim CH, Choi HS, Kim SM. Prognostic value of serum CA-125 in patients with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer followed by complete remission after adjuvant chemotherapy. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2013;56:29-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | van Altena AM, Kolwijck E, Spanjer MJ, Hendriks JC, Massuger LF, de Hullu JA. CA125 nadir concentration is an independent predictor of tumor recurrence in patients with ovarian cancer: a population-based study. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;119:265-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chen X, Zhang J, Cheng W, Chang DY, Huang J, Wang X, Jia L, Rosen DG, Zhang W, Yang D, Gershenson DM, Sood AK, Bast RC Jr, Liu J. CA-125 level as a prognostic indicator in type I and type II epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013;23:815-822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Moore RG, Miller MC, Steinhoff MM, Skates SJ, Lu KH, Lambert-Messerlian G, Bast RC Jr. Serum HE4 levels are less frequently elevated than CA125 in women with benign gynecologic disorders. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012; 206: 351.e1-351. e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kafali H, Artuc H, Demir N. Use of CA125 fluctuation during the menstrual cycle as a tool in the clinical diagnosis of endometriosis; a preliminary report. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004;116:85-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Liou JH, Su TC, Hsu JC. Meigs' syndrome with elevated serum cancer antigen 125 levels in a case of ovarian sclerosing stromal tumor. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;50:196-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |