Published online Jul 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i21.5769

Peer-review started: January 29, 2021

First decision: March 29, 2021

Revised: April 12, 2021

Accepted: June 2, 2021

Article in press: June 2, 2021

Published online: July 26, 2021

Processing time: 172 Days and 15.1 Hours

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation can lead to severe acute hepatic failure and death in patients with HBV infection. HBV reactivation (HBVr) most commonly develops in patients undergoing cancer chemotherapy, especially B cell-depleting agent therapy such as rituximab and ofatumumab for hematological or solid organ malignancies and that receiving hematopoietic stem cell transplantation without antiviral prophylaxis. In addition, the potential consequences of HBVr is particularly a concern when patients are exposed to either immunosuppressive or biologic therapies for the management of rheumatologic diseases, inflammatory bowel disease and dermatologic diseases. Thus, screening with HBV serological markers and prophylactic or pre-emptive antiviral treatment with nucleos(t)ide analogues should be considered in these patients to diminish the risk of HBVr. This review discusses the clinical manifestation, prognosis and management of HBVr, risk stratifications of cancer chemotherapy and immunosuppressive therapy and international guideline recommendations for the prevention of HBVr in patients with HBV infection and resolved hepatitis B.

Core Tip: Reactivation of hepatitis B virus (HBV) could be fatal in the patients with hepatitis B infection and chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy. We review the risk of HBV reactivation, screening of HBV infection and the strategies of prophylaxis of HBV reactivation in patients requiring chemotherapy and immunosuppressive therapy.

- Citation: Shih CA, Chen WC. Prevention of hepatitis B reactivation in patients requiring chemotherapy and immunosuppressive therapy. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(21): 5769-5781

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i21/5769.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i21.5769

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a virus containing a DNA genome of 3226 base pairs that can cause a potentially life-threatening liver infection[1,2]. About 2 billion people have been infected with HBV worldwide; of which, 350 million are in chronic infection status[3,4]. HBV is one of the most frequently identified pathogens that lead to acute and chronic hepatitis, acute liver failure and death in East Asia. Three quarters of the HBV carries reside in the Asia-Pacific region[5]. Nevertheless, northern, western and central Europe, North America and Australia are among the lowest prevalence area of chronic HBV infection [hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)-positive, 0.2% to 0.5%] and HBV exposure [HBsAg-negative but hepatitis B core antibodies (anti-HBc)-positive, 4% to 6%], while Eastern Europe, the Mediterranean, Russia, Southwest Asia and Central and South America have higher prevalence rates (2% to 7% chronically infected and 20% to 55% exposed). Southeast Asia, China and tropical Africa have the highest prevalence rates (8% to 20% chronically infected and 70% to 95% exposed)[3].

Patients infected with HBV, either chronic or resolved HBV infection cases, are at risk of HBV reactivation (HBVr) when they undergo chemotherapy. HBVr could occur in patients receiving chemotherapy for hematological malignancies or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) recipients as well as patients receiving treatment for solid tumors such as breast cancer[6]. In HBsAg-positive lymphoma patients under

The recent American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) reco

The clinical manifestations of HBVr vary from absence of symptoms to liver decom

The occurrence of HBVr largely depends on the primary disease requiring chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy, host immunity, underlying disease and the immunosuppressive agents used. HBVr may occur as early as within the first 2 wk or up to a year after the cessation of chemotherapy and immunosuppressive therapy. Identifying the risk factors and mechanisms associated with HBVr could help quantify the risk of HBVr and manage the clinical consequences[13].

The clinical course of HBVr could be divided into three stages[14,15]. During the first stage, there is a gradual or abrupt increase in serum levels of HBV DNA in HBsAg-positive patients, reappearance of serum HBsAg in patients previously seronegative for HBsAg or reappearance of serum HBV DNA in patients with undetectable HBV DNA before chemotherapy and immunosuppressive therapy. Symptoms of hepatitis are usually absent and the levels of aminotransferases are not elevated at this stage[6]. During the second stage, serum HBV DNA levels increase persistently with elevated aminotransferases levels. The symptoms associated with hepatitis could be present or absent. In cases with severe hepatitis flare up, hepatic injury could further progress and cause liver failure and even death. These changes could occur during treatment duration of chemotherapy and immunosuppressive therapy or after discontinuation of the treatments and may occur with restoration of the host immunity[6,16]. During the third stage, liver injury could resolve after withholding chemotherapy and immunosuppression agents or administration of antivirals[6].

HBVr could develop during or after discontinuation of chemotherapy and immuno

Occurrence of HBVr may delay or hamper scheduled chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy and result in progression of underlying diseases. A study of patients receiving chemotherapy for breast cancer revealed that early discontinuation of chemotherapy or a delay in the scheduled therapy occurred in about 70% of cases with HBVr, corresponding to the figure of only 33% in cases without HBVr[18].

The main risk factors associated with HBVr could be divided into three categories: (1) host factors; (2) virological factors; and (3) type of immunosuppressive regimen. The host factors include male sex, older age, presence of liver cirrhosis and type of diseases requiring immunosuppression[19,20].

Younger age and male gender are among the risk factors for HBVr[20]. On the contrary, another study reported old age as a risk factor[12,21]. It has also been found that patients with older age tend to have more virologic conditions (HBsAg positivity, persistently detectable serum HBV DNA and presence of covalently closed circular DNA in the liver), which increase the risk of HBVr[22,23].

The extent of HBV replication before the start of chemotherapy and immunosuppressive therapy is an important risk factor for HBVr. Patients seropositive for HBsAg are at a higher risk of HBVr than those seronegative for HBsAg and seropositive for anti-HBc. Patients seropositive for HBsAg are at a 5- to 8-fold risk for HBVr[6,24]. In the patients receiving chemotherapy for lymphoma, the prevalence rate of HBVr could be 48% in HBsAg-positive patients, 4% in HBsAg-negative/anti-HBc-positive patients and 0% in HBsAg-negative/anti-HBc-negative patients[12,25]. The liver failure could occur in 7% of HBsAg-positive patients, 2% of HBsAg-negative/anti-HBc-positive patients and 0% of HBsAg-negative/anti-HBc-negative patients[12,25].

Patients with resolved HBV infection (HBsAg-negative, anti-HBc-positive) could have occult HBV infection with persistent detectable HBV DNA[26-28]. The HBVr rate ranges from 8.9% to 41.5% in occult HBV infection patients receiving rituximab-containing chemotherapy in different studies using the definitions of HBsAg seroreversion or detectable HBV DNA[29-31]. In a multicenter, randomized, phase 3 study of 326 diffuse large B-cell lymphoma or follicular lymphoma patients with resolved HBV infection, 27 (8.2%) had HBVr that occurred at a median of 125 d after the first dose of obinutuzumab or rituximab immunochemotherapy. Twenty-five of 232 patients (10.8%) without prophylactic nucleos(t)ides had HBVr while only 2 of 94 patients (2.1%) with prophylactic nucleos(t)ides had HBVr[32]. Thus, prophylactic nucleos(t)ides should be used in resolved HBV infection patients receiving rituximab-containing regimens for hematological or rheumatological disease[33].

The risk of HBVr could be graded according to the potency of immunosuppression agents used as followed: (1) High risk: HBVr rate of more than 10% (anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies including rituximab; systemic cancer chemotherapy agents such as doxorubicin); (2) Moderate risk: HBVr rate of 1% to 10% (imatinib, ibrutinib and other tyrosine kinase inhibitors; corticosteroids dosage equivalent to more than prednisone 20 mg daily use for more than 4 wk); and (3) Low risk: HBVr rate of less than 1% (traditional immunosuppressive agents such as azathioprine and metho

| Risk group | Seropositive for HBsAg and anti-HBc | Seronegative for HBsAg, seropositive for anti-HBc |

| High risk (> 10%) | Anti-CD20 antibodies | Anti-CD20 antibodies |

| Anti-CD52 antibodies | ||

| Anthracycline derivatives | ||

| Costimulation inhibitors | ||

| JAK inhibitors | ||

| Moderate-high dose corticosteroid therapy1 for ≥ 4 wk | ||

| Moderate risk (1%-10%) | TNF-α inhibitors | Anthracycline derivatives |

| Integrin inhibitors | TNF-α inhibitors | |

| IL-12 and IL-23 antibodies | Integrin inhibitors | |

| Tyrosine kinase inhibitors | IL-12 and IL-23 antibodies | |

| Low dose corticosteroid therapy1 for ≥ 4 wk | Tyrosine kinase inhibitors | |

| Moderate-high dose corticosteroid therapy1 for ≥ 4 wk | ||

| Low risk (< 1%) | General immunosuppressive agents (azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine and methotrexate) | General immunosuppressive agents (azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine and methotrexate) |

| Corticosteroid therapy1 for ≤ 1 wk | Low dose corticosteroid therapy1 for ≥ 4 wk | |

| Intra-articular corticosteroids | Corticosteroid therapy1 for ≤ 1 wk | |

| Intra-articular corticosteroids |

The studies of chemotherapy-associated HBVr were most often investigated in hematologic malignancies such as non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma[7,25,34]. B-cell proliferation and lymphocytes infected by HBV also could be observed in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients seronegative for HBsAg[22]. HBVr has been investigated in multiple myeloma patients seropositive for HBsAg or seronegative for HBsAg but seropositive for anti-HBc[35-37]. Multiple myeloma patients with immune dysfunction are prone to develop HBVr[38]. We recommend antiviral prophylaxis in HBsAg-positive patients from 1 wk before starting immunosuppressive agents and until 12 mo after discontinuation of the agents. We also recommend that patients seronegative for HBsAg but seropositive for anti-HBc on drugs targeting B lymphocytes should be provided with antiviral prophylaxis.

The incidence of HBVr associated with systemic cytotoxic chemotherapy ranged from 20% to 36% in solid tumor patients including breast cancer, lung cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and nasopharyngeal cancer who were seropositive for HBsAg[39]. Severe HBVr may occur in 4.3% of HBsAg-positive patients with solid tumors who received chemotherapy without antiviral prophylaxis[7]. Breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy are associated with 25% to 40% incidence of HBVr[18,40]. The HBVr rate associated with breast cancer is higher than that associated with other solid cancers (7% to 29%) because anthracycline and corticosteroids are frequently used[41]. We recommend antiviral prophylaxis in HBsAg-positive patients from 1 wk before starting immunosuppressive agents until 12 mo after discontinuation of the agents. At present there are insufficient data to recommend antiviral prophylaxis in HBsAg-negative/anti-HBc-positive patients.

The incidence of HBVr in patients with HCC ranges between 4% and 67%[12,42]. In fact, HBVr can occur during curative or palliative therapies for HCC such as hepatectomy, local ablation, transarterial chemoembolization, systemic chemotherapy and radiation therapy[43]. In HBsAg-positive patients with HCC who were treated with transarterial chemoembolization, 33.7% had HBVr[43]. Of the patients sero

Patients undergoing allogeneic HSCT are at the highest risk of HBVr because of high-dose chemotherapy and potent immunosuppressive agents to prevent the rejection of the graft[6]. In HBsAg-positive patients receiving HSCT, 57.6% developed HBVr[45]. HBVr is also not uncommon in patients seronegative for HBsAg but seropositive for anti-HBc undergoing HSCT, with a rate of HBsAg seroreversion of 20% in a retro

The incidences of HBVr in patients with rheumatologic disease such as rheumatoid arthritis could be up to 12.3% in patients seropositive for HBsAg[47] and 3% to 5% in patients seronegative for HBsAg but seropositive for anti-HBc-positive[12,48]. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors (e.g., etanercept, infliximab and adalimumab) when administered in rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis patients seropositive for HBsAg are associated with an HBVr rate of 1% to 10%. On the contrary, the reactivation risk is only around 1% in patients seronegative for HBsAg but seropositive for anti-HBc[49]. Therefore, we recommend that HBV prophylaxis may not be indicated in patients seronegative for HBsAg but seropositive for anti-HBc-positive while they could be monitored for hepatic biochemical flare during immunosuppression.

The HBVr rates in patients with inflammatory bowel disease range between 0.6% and 36.0% for patients seropositive for HBsAg[50]. The rate ranges between 1.6% and 42.0% for patients seronegative for HBsAg but seropositive for anti-HBc[50]. With the use of tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors and other biologic agents, HBVr including hepatic failure has been reported[51,52]. We recommend that HBsAg-negative, anti-HBc-positive patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, biologicals or conventional immunosuppressive therapies could be monitored without anti-HBV prophylaxis.

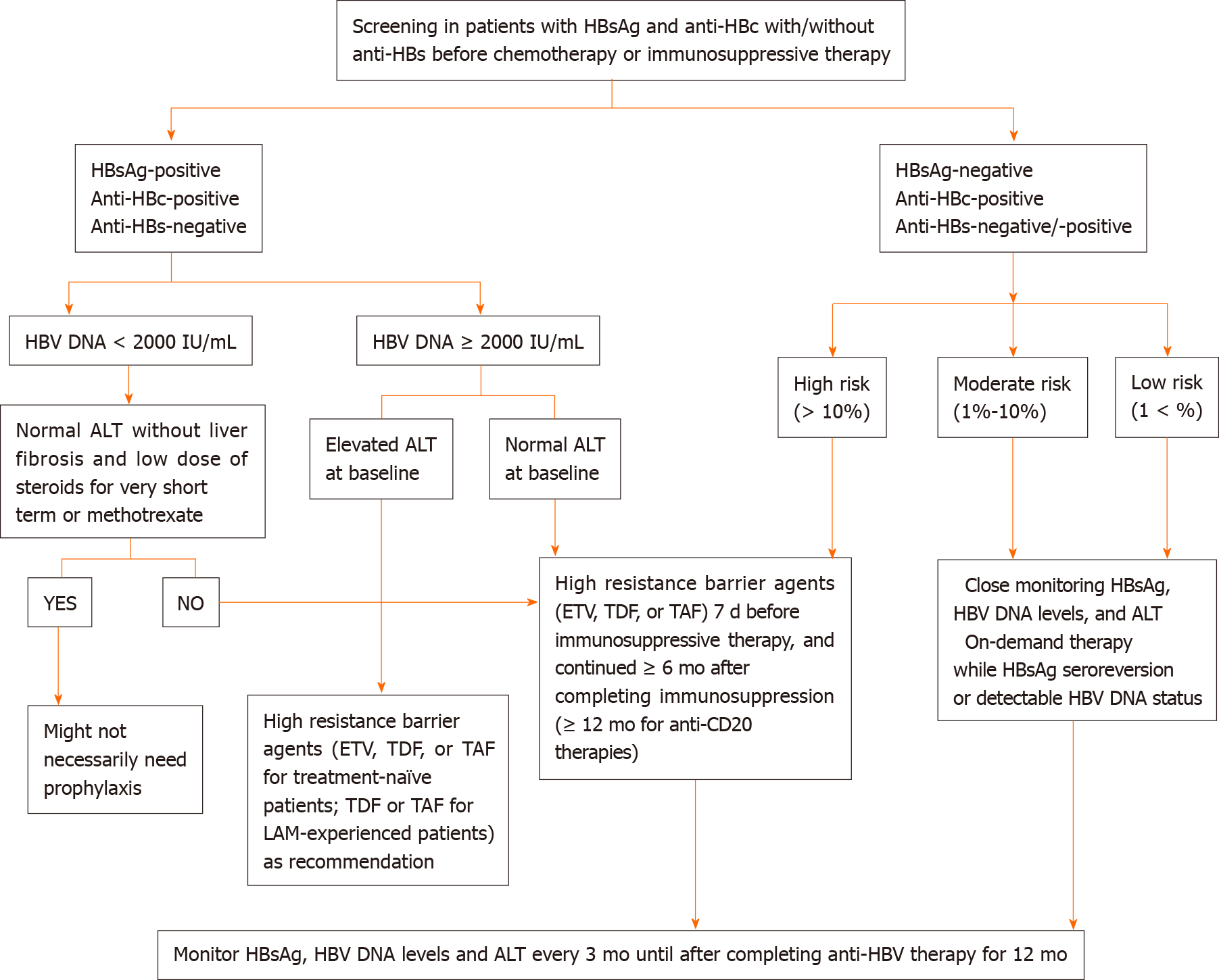

The strategies of screening for HBV before starting chemotherapy and immunosuppressive therapies vary between the recommendations[53-57]. The patients undergoing these therapies that carry a high or moderate risk of HBVr should be screened for HBsAg and anti-HBc with or without checking anti-HBs. The patients seronegative for HBsAg, anti-HBc and anti-HBs could be vaccinated against HBV[13].

The risk of HBVr could be categorized into high risk (> 10%), moderate risk (1%-10%) and low risk (< 1%) according to the risk of reactivation (Table 1)[49,54,58].

B-cell depleting agents such as rituximab are associated with a high risk for HBVr and thus antiviral prophylaxis should be administered in the patients exposed to HBV regardless of the HBsAg status[59]. These patients should be given prophylactic antivirals (entecavir or tenofovir preferred) before the start of chemotherapy and immunosuppressive treatments[12]. Monitoring for HBVr should continue for another 6 to 12 mo after the cessation of prophylactic antivirals[60].

Pre-emptive therapy is defined as antivirals initiated at the rise of serum HBV DNA or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels but before the onset of hepatitis symptoms or liver failure. Primary prophylaxis therapy is defined as antivirals started before or at the initiation of immunosuppressive agents and before rise in HBV DNA or ALT levels. In HBsAg-negative and anti-HBc positive subjects with moderate (< 10%) or low (< 1%) risk of HBVr, pre-emptive therapy, instead of prophylactic therapy, is generally recommended[60]. Pre-emptive therapy is based on monitoring HBsAg and/or HBV DNA at 1 to 3 mo intervals during and after immunosuppression and starting antiviral therapy in case of detectable HBV DNA or HBsAg seroreversion[60].

Close monitoring of HBsAg, HBV DNA and ALT levels with on-demand antiviral therapy could be offered for the patients who carry a low risk for HBVr.

Screening of HBV using tests including HBsAg, anti-HBc and anti-HBs should be performed before the initiation of chemotherapy or immunosuppressive agents. Patients seropositive for HBsAg with serum HBV DNA level of equal to or greater than 2000 IU/mL and an increased ALT level should start nucleos(t)ide analogues as recommended by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases guidelines[11]. A proposed algorithm of HBVr prophylaxis and treatment for patients receiving chemotherapy and immunosuppressive therapy are described in Figure 1[11,58,60,61].

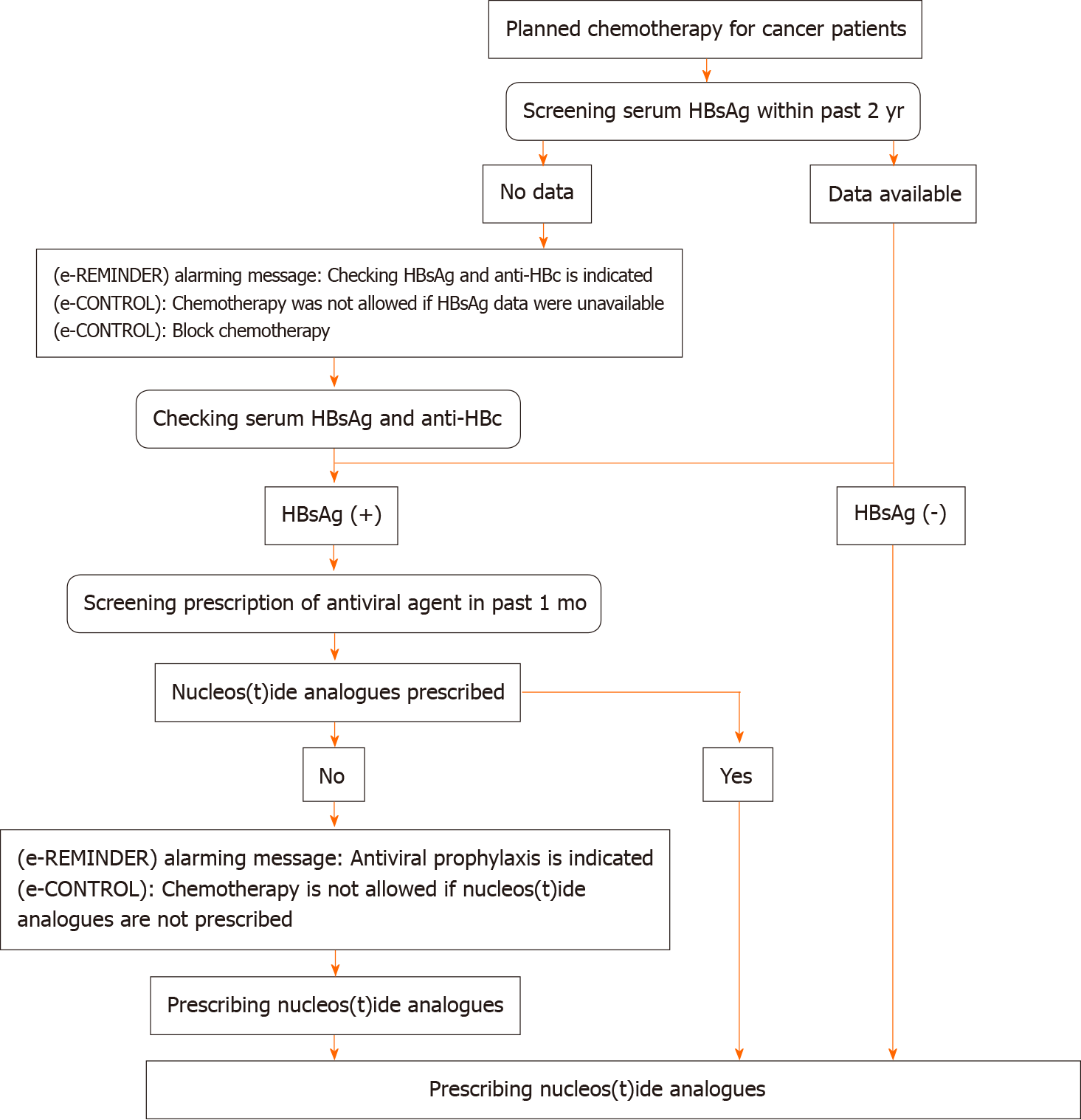

Given the fact that screening for HBV before chemotherapy and immunosuppressive therapy with prophylactic antiviral agents could significantly decrease the occurrence of HBVr, the screening rates remain relatively low in non-HBV endemic countries such as the United States (17%) and Canada (14% to 31%)[62-64]. A retro

Prophylactic lamivudine significantly decreases the risk of HBVr, hepatitis and mortality in patients undergoing chemotherapy[19,66]. Pre-emptive therapy with lamivudine before the initiation of chemotherapy also decreases the risk of interruption of cancer chemotherapy.

The main concern about lamivudine is that the genetic barrier is relatively low, although it is effective for the prophylaxis of HBVr[19,55]. The resistance rates of lamivudine are 20% and 30% at 1 and 2 years, respectively, and increase exponentially thereafter[55]. In some countries, the use of lamivudine, adefovir and telbivudine (agents with low genetic barriers) may be considered because of the low cost. This is particularly true for patients seropositive for HBsAg with undetectable or very low levels of serum HBV DNA[13]. Entecavir or tenofovir is the agent of choice for the prophylaxis of HBVr because these antivirals have a high genetic barrier[54,55,67]. In a randomized, controlled trial comparing entecavir 0.5 mg daily and lamivudine 100 mg daily in prophylaxis of HBVr in lymphoma patients seropositive for HBsAg receiving rituximab-containing chemotherapy, entecavir was superior to lamivudine in terms of decreasing the risk of developing hepatitis (0% vs 13.3%), HBVr (6.6% vs 30.0%) and disruption of chemotherapy (1.6% vs 18.3%)[67]. As for the patients undergoing systemic cytotoxic chemotherapy for solid tumors, antiviral prophylaxis reduced the risk for HBVr, HBV-related hepatitis and chemotherapy interruption[68]. Entecavir was superior to lamivudine with less incidence of HBVr in the patients with a baseline HBV DNA level ≥ 2000 IU/mL[39]. A recent meta-analysis revealed that both tenofovir and entecavir could be the most efficacious therapies in the prophylaxis of HBVr[69]. Table 2 summarizes the recommendations for treatment and follow-up in different clinical scenarios and choice of antiviral agents. Most experts recommend routine screening before cancer chemotherapy[70,71].

| AASLD 2018 | EASL 2017 | APASL 2016 | AGA 2015 | |

| Screening before chemotherapy/immunosuppressive therapy | HBsAg and anti-HBc | HBsAg, anti-HBc, and anti-HBs | HBsAg and anti-HBc | HBsAg and anti-HBc |

| HBV DNA if serology positive | ||||

| Start antiviral prophylaxis before chemotherapy/immunosuppressive therapy | For HBsAg (+) patients | For HBsAg (+) patients | For HBsAg (+) patients | For HBsAg (+) patients |

| For HBsAg (-)/anti-HBc (+) patients: if at high risk of HBV reactivation | For HBsAg (-)/anti-HBc (+) patients: if detectable serum HBV DNA | For HBsAg (-)/anti-HBc (+) patients: If the chemotherapy is associated with high or moderate risk of HBV reactivation | ||

| Treatment duration of antiviral treatment after completing chemotherapy/immunosuppressive therapy | At least 6 mo | 12 mo | 12 mo | At least 6 mo |

| At least 12 mo for patients receiving anti-CD20 antibodies therapy | At least 12 mo for patient receiving anti-CD20 antibodies therapy | |||

| Antivirals of choice | TDF, TAF or ETV | TDF, TAF or ETV | TDF and ETV | TDF and ETV |

No standard strategy has hitherto been established to prevent HBVr in patients with resolved HBV infection. A recent meta-analysis with 13 studies showed no association between antiviral prophylaxis and risk of HBVr in patients with resolved hepatitis B[72]. Nevertheless, providing antiviral prophylaxis to the patients receiving rituximab-containing therapy could be considered[72]. Huang et al[27] recently revealed that HBVr and HBsAg seroreversion were not uncommon in patients with lymphoma and resolved hepatitis B, and entecavir prophylaxis could significantly prevent rituximab-associated HBVr[27]. In patients with hematological malignancy and resolved hepatitis B receiving rituximab-containing regimens, tenofovir effectively prevents the occurrence of HBVr[73]. Prophylactic lamivudine may be considered only in the patients without HBV viremia[74].

HBVr is increasingly recognized as a clinical challenge with a risk of significant morbidity and mortality. Development of HBVr with an increase in serum HBV DNA and aminotransferases could occur in 20% to 50% of HBV carriers undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy for cancer treatment or immunosuppressive therapy with a mortality rate of approximately 5%[75].

Screening for HBV before immunosuppression and chemotherapy is required to prevent the occurrence of HBVr. Screening tests including HBsAg and anti-HBc with or without anti-HBs in the patients about to start anticancer and immunosuppressive therapy is recommended. An integrated strategy involving screening the patients at risk, stratifying the patients for risk according to the status of HBV and the type of immunosuppressive agents administered and careful evaluation of the prophylactic therapy could significantly lower the risk of HBVr.

Entecavir or tenofovir are preferred over lamivudine as antiviral therapy for the prophylaxis of HBVr. The optimal duration of prophylactic antiviral therapy remains to be defined. Current international guidelines suggest administration of prophylactic antiviral therapy for at least 6 to 12 mo after the completion of chemotherapy and even longer for rituximab users or patients with high serum HBV DNA levels before the start of chemotherapy. However, patients with chronic hepatitis B or cirrhosis should continue antiviral therapy regardless of the duration of chemotherapy. Aggressive screening of HBV with adequate antiviral prophylaxis is the optimal strategy for preventing HBVr during chemotherapy and immunosuppressive therapy.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Taiwan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Hussaini T, Ko HH S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Kawsar HI, Shahnewaz J, Gopalakrishna KV, Spiro TP, Daw HA. Hepatitis B reactivation in cancer patients: role of prechemotherapy screening and antiviral prophylaxis. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2012;10:370-378. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Liaw YF, Chu CM. Hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet. 2009;373:582-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 929] [Cited by in RCA: 980] [Article Influence: 61.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Pattullo V. Hepatitis B reactivation in the setting of chemotherapy and immunosuppression - prevention is better than cure. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:954-967. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lee WM. Hepatitis B virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1733-1745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1728] [Cited by in RCA: 1712] [Article Influence: 61.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mohamed R, Desmond P, Suh DJ, Amarapurkar D, Gane E, Guangbi Y, Hou JL, Jafri W, Lai CL, Lee CH, Lee SD, Lim SG, Guan R, Phiet PH, Piratvisuth T, Sollano J, Wu JC. Practical difficulties in the management of hepatitis B in the Asia-Pacific region. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:958-969. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Law MF, Ho R, Cheung CK, Tam LH, Ma K, So KC, Ip B, So J, Lai J, Ng J, Tam TH. Prevention and management of hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients with hematological malignancies treated with anticancer therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:6484-6500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shih CA, Chen WC, Yu HC, Cheng JS, Lai KH, Hsu JT, Chen HC, Hsu PI. Risk of Severe Acute Exacerbation of Chronic HBV Infection Cancer Patients Who Underwent Chemotherapy and Did Not Receive Anti-Viral Prophylaxis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ling WH, Soe PP, Pang AS, Lee SC. Hepatitis B virus reactivation risk varies with different chemotherapy regimens commonly used in solid tumours. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:1931-1935. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lau GK, Liang R, Chiu EK, Lee CK, Lam SK. Hepatic events after bone marrow transplantation in patients with hepatitis B infection: a case controlled study. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997;19:795-799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Dai MS, Wu PF, Shyu RY, Lu JJ, Chao TY. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in breast cancer patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy and the role of preemptive lamivudine administration. Liver Int. 2004;24:540-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Terrault NA, Lok ASF, McMahon BJ, Chang KM, Hwang JP, Jonas MM, Brown RS Jr, Bzowej NH, Wong JB. Update on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidance. Hepatology. 2018;67:1560-1599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2290] [Cited by in RCA: 2823] [Article Influence: 403.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Choi J, Lim YS. Characteristics, Prevention, and Management of Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) Reactivation in HBV-Infected Patients Who Require Immunosuppressive Therapy. J Infect Dis. 2017;216:S778-S784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Loomba R, Liang TJ. Hepatitis B Reactivation Associated With Immune Suppressive and Biological Modifier Therapies: Current Concepts, Management Strategies, and Future Directions. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1297-1309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 426] [Cited by in RCA: 439] [Article Influence: 54.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hwang JP, Lok AS. Management of patients with hepatitis B who require immunosuppressive therapy. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11:209-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hoofnagle JH. Reactivation of hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2009;49:S156-S165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 412] [Cited by in RCA: 430] [Article Influence: 26.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lalazar G, Rund D, Shouval D. Screening, prevention and treatment of viral hepatitis B reactivation in patients with haematological malignancies. Br J Haematol. 2007;136:699-712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Evens AM, Jovanovic BD, Su YC, Raisch DW, Ganger D, Belknap SM, Dai MS, Chiu BC, Fintel B, Cheng Y, Chuang SS, Lee MY, Chen TY, Lin SF, Kuo CY. Rituximab-associated hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation in lymphoproliferative diseases: meta-analysis and examination of FDA safety reports. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1170-1180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 241] [Cited by in RCA: 271] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yeo W, Chan PK, Hui P, Ho WM, Lam KC, Kwan WH, Zhong S, Johnson PJ. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in breast cancer patients receiving cytotoxic chemotherapy: a prospective study. J Med Virol. 2003;70:553-561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Loomba R, Rowley A, Wesley R, Liang TJ, Hoofnagle JH, Pucino F, Csako G. Systematic review: the effect of preventive lamivudine on hepatitis B reactivation during chemotherapy. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:519-528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 370] [Cited by in RCA: 354] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Yeo W, Chan PK, Zhong S, Ho WM, Steinberg JL, Tam JS, Hui P, Leung NW, Zee B, Johnson PJ. Frequency of hepatitis B virus reactivation in cancer patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy: a prospective study of 626 patients with identification of risk factors. J Med Virol. 2000;62:299-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | An J, Shim JH, Kim SO, Choi J, Kim SW, Lee D, Kim KM, Lim YS, Lee HC, Chung YH, Lee YS, Suh DJ. Comprehensive outcomes of on- and off-antiviral prophylaxis in hepatitis B patients undergoing cancer chemotherapy: A competing risks analysis. J Med Virol. 2016;88:1576-1586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sagnelli C, Pisaturo M, Calò F, Martini S, Sagnelli E, Coppola N. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus infection in patients with hemo-lymphoproliferative diseases, and its prevention. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:3299-3312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yuen MF, Wong DK, Fung J, Ip P, But D, Hung I, Lau K, Yuen JC, Lai CL. HBsAg Seroclearance in chronic hepatitis B in Asian patients: replicative level and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1192-1199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 306] [Cited by in RCA: 321] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Shouval D, Shibolet O. Immunosuppression and HBV reactivation. Semin Liver Dis. 2013;33:167-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lok AS, Liang RH, Chiu EK, Wong KL, Chan TK, Todd D. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus replication in patients receiving cytotoxic therapy. Report of a prospective study. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:182-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 631] [Cited by in RCA: 616] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Fopa D, Candotti D, Tagny CT, Doux C, Mbanya D, Murphy EL, Kenawy HI, El Chenawi F, Laperche S. Occult hepatitis B infection among blood donors from Yaoundé, Cameroon. Blood Transfus. 2019;17:403-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Huang YH, Hsiao LT, Hong YC, Chiou TJ, Yu YB, Gau JP, Liu CY, Yang MH, Tzeng CH, Lee PC, Lin HC, Lee SD. Randomized controlled trial of entecavir prophylaxis for rituximab-associated hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients with lymphoma and resolved hepatitis B. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2765-2772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 22.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Di Bisceglie AM, Lok AS, Martin P, Terrault N, Perrillo RP, Hoofnagle JH. Recent US Food and Drug Administration warnings on hepatitis B reactivation with immune-suppressing and anticancer drugs: just the tip of the iceberg? Hepatology. 2015;61:703-711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Hsu C, Tsou HH, Lin SJ, Wang MC, Yao M, Hwang WL, Kao WY, Chiu CF, Lin SF, Lin J, Chang CS, Tien HF, Liu TW, Chen PJ, Cheng AL; Taiwan Cooperative Oncology Group. Chemotherapy-induced hepatitis B reactivation in lymphoma patients with resolved HBV infection: a prospective study. Hepatology. 2014;59:2092-2100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Matsue K, Kimura S, Takanashi Y, Iwama K, Fujiwara H, Yamakura M, Takeuchi M. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus after rituximab-containing treatment in patients with CD20-positive B-cell lymphoma. Cancer. 2010;116:4769-4776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Seto WK, Chan TS, Hwang YY, Wong DK, Fung J, Liu KS, Gill H, Lam YF, Lie AK, Lai CL, Kwong YL, Yuen MF. Hepatitis B reactivation in patients with previous hepatitis B virus exposure undergoing rituximab-containing chemotherapy for lymphoma: a prospective study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3736-3743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 22.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kusumoto S, Arcaini L, Hong X, Jin J, Kim WS, Kwong YL, Peters MG, Tanaka Y, Zelenetz AD, Kuriki H, Fingerle-Rowson G, Nielsen T, Ueda E, Piper-Lepoutre H, Sellam G, Tobinai K. Risk of HBV reactivation in patients with B-cell lymphomas receiving obinutuzumab or rituximab immunochemotherapy. Blood. 2019;133:137-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Cholongitas E, Haidich AB, Apostolidou-Kiouti F, Chalevas P, Papatheodoridis GV. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in HBsAg-negative, anti-HBc-positive patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy: a systematic review. Ann Gastroenterol. 2018;31:480-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Hsu C, Hsiung CA, Su IJ, Hwang WS, Wang MC, Lin SF, Lin TH, Hsiao HH, Young JH, Chang MC, Liao YM, Li CC, Wu HB, Tien HF, Chao TY, Liu TW, Cheng AL, Chen PJ. A revisit of prophylactic lamivudine for chemotherapy-associated hepatitis B reactivation in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a randomized trial. Hepatology. 2008;47:844-853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 243] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Mya DH, Han ST, Linn YC, Hwang WY, Goh YT, Tan DC. Risk of hepatitis B reactivation and the role of novel agents and stem-cell transplantation in multiple myeloma patients with hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:421-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Lee JY, Lim SH, Lee MY, Kim H, Sinn DH, Gwak GY, Choi MS, Lee JH, Jung CW, Jang JH, Kim WS, Kim SJ, Kim K. Hepatitis B reactivation in multiple myeloma patients with resolved hepatitis B undergoing chemotherapy. Liver Int. 2015;35:2363-2369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Li J, Huang B, Li Y, Zheng D, Zhou Z, Liu J. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients with multiple myeloma receiving bortezomib-containing regimens followed by autologous stem cell transplant. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56:1710-1717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Feyler S, Selby PJ, Cook G. Regulating the regulators in cancer-immunosuppression in multiple myeloma (MM). Blood Rev. 2013;27:155-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Chen WC, Cheng JS, Chiang PH, Tsay FW, Chan HH, Chang HW, Yu HC, Tsai WL, Lai KH, Hsu PI. A Comparison of Entecavir and Lamivudine for the Prophylaxis of Hepatitis B Virus Reactivation in Solid Tumor Patients Undergoing Systemic Cytotoxic Chemotherapy. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0131545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Yun J, Kim KH, Kang ES, Gwak GY, Choi MS, Lee JE, Nam SJ, Yang JH, Park YH, Ahn JS, Im YH. Prophylactic use of lamivudine for hepatitis B exacerbation in post-operative breast cancer patients receiving anthracycline-based adjuvant chemotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2011;104:559-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Yeo W, Zee B, Zhong S, Chan PK, Wong WL, Ho WM, Lam KC, Johnson PJ. Comprehensive analysis of risk factors associating with Hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation in cancer patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:1306-1311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Jang JW. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing anti-cancer therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:7675-7685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Jang JW, Choi JY, Bae SH, Kim CW, Yoon SK, Cho SH, Yang JM, Ahn BM, Lee CD, Lee YS, Chung KW, Sun HS. Transarterial chemo-lipiodolization can reactivate hepatitis B virus replication in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2004;41:427-435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Jang JW, Kim YW, Lee SW, Kwon JH, Nam SW, Bae SH, Choi JY, Yoon SK, Chung KW. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus in HBsAg-negative patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0122041. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Locasciulli A, Bruno B, Alessandrino EP, Meloni G, Arcese W, Bandini G, Cassibba V, Rotoli B, Morra E, Majolino I, Alberti A, Bacigalupo A; Italian Cooperative Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Hepatitis reactivation and liver failure in haemopoietic stem cell transplants for hepatitis B virus (HBV)/hepatitis C virus (HCV) positive recipients: a retrospective study by the Italian group for blood and marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003;31:295-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Hammond SP, Borchelt AM, Ukomadu C, Ho VT, Baden LR, Marty FM. Hepatitis B virus reactivation following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:1049-1059. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Lee YH, Bae SC, Song GG. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in HBsAg-positive patients with rheumatic diseases undergoing anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy or DMARDs. Int J Rheum Dis. 2013;16:527-531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Urata Y, Uesato R, Tanaka D, Kowatari K, Nitobe T, Nakamura Y, Motomura S. Prevalence of reactivation of hepatitis B virus replication in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Mod Rheumatol. 2011;21:16-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Perrillo RP, Gish R, Falck-Ytter YT. American Gastroenterological Association Institute technical review on prevention and treatment of hepatitis B virus reactivation during immunosuppressive drug therapy. Gastroenterology 2015; 148: 221-244. e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 352] [Cited by in RCA: 390] [Article Influence: 39.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 50. | Loras C, Gisbert JP, Mínguez M, Merino O, Bujanda L, Saro C, Domenech E, Barrio J, Andreu M, Ordás I, Vida L, Bastida G, González-Huix F, Piqueras M, Ginard D, Calvet X, Gutiérrez A, Abad A, Torres M, Panés J, Chaparro M, Pascual I, Rodriguez-Carballeira M, Fernández-Bañares F, Viver JM, Esteve M; REPENTINA study; GETECCU (Grupo Español de Enfermedades de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa) Group. Liver dysfunction related to hepatitis B and C in patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with immunosuppressive therapy. Gut. 2010;59:1340-1346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Esteve M, Saro C, González-Huix F, Suarez F, Forné M, Viver JM. Chronic hepatitis B reactivation following infliximab therapy in Crohn's disease patients: need for primary prophylaxis. Gut. 2004;53:1363-1365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 331] [Cited by in RCA: 363] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Loras C, Gisbert JP, Saro MC, Piqueras M, Sánchez-Montes C, Barrio J, Ordás I, Montserrat A, Ferreiro R, Zabana Y, Chaparro M, Fernández-Bañares F, Esteve M; REPENTINA study; GETECCU group (Grupo Español de trabajo de Enfermedades de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa). Impact of surveillance of hepatitis b and hepatitis c in patients with inflammatory bowel disease under anti-TNF therapies: multicenter prospective observational study (REPENTINA 3). J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1529-1538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Doo EC, Hoofnagle JH, Rodgers GP. NIH consensus development conference: management of Hepatitis B. Introduction. Hepatology. 2009;49:S1-S3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Reddy KR, Beavers KL, Hammond SP, Lim JK, Falck-Ytter YT; American Gastroenterological Association Institute. American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on the prevention and treatment of hepatitis B virus reactivation during immunosuppressive drug therapy. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:215-9; quiz e16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 508] [Cited by in RCA: 450] [Article Influence: 45.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology. 2009;50:661-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2125] [Cited by in RCA: 2169] [Article Influence: 135.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Khokhar OS, Farhadi A, McGrail L, Lewis JH. Oncologists and hepatitis B: a survey to determine current level of awareness and practice of antiviral prophylaxis to prevent reactivation. Chemotherapy. 2009;55:69-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Sarin SK, Kumar M, Lau GK, Abbas Z, Chan HL, Chen CJ, Chen DS, Chen HL, Chen PJ, Chien RN, Dokmeci AK, Gane E, Hou JL, Jafri W, Jia J, Kim JH, Lai CL, Lee HC, Lim SG, Liu CJ, Locarnini S, Al Mahtab M, Mohamed R, Omata M, Park J, Piratvisuth T, Sharma BC, Sollano J, Wang FS, Wei L, Yuen MF, Zheng SS, Kao JH. Asian-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatitis B: a 2015 update. Hepatol Int. 2016;10:1-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1985] [Cited by in RCA: 1950] [Article Influence: 216.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Ekpanyapong S, Reddy KR. Hepatitis B Virus Reactivation: What Is the Issue, and How Should It Be Managed? Clin Liver Dis. 2020;24:317-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Koffas A, Dolman GE, Kennedy PT. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients treated with immunosuppressive drugs: a practical guide for clinicians. Clin Med (Lond). 2018;18:212-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2017;67:370-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3745] [Cited by in RCA: 3775] [Article Influence: 471.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 61. | Arora A, Anand AC, Kumar A, Singh SP, Aggarwal R, Dhiman RK, Aggarwal S, Alam S, Bhaumik P, Dixit VK, Goel A, Goswami B, Kumar M, Madan K, Murugan N, Nagral A, Puri AS, Rao PN, Saraf N, Saraswat VA, Sehgal S, Sharma P, Shenoy KT, Wadhawan M; Members of the INASL taskforce on Hepatitis B. INASL Guidelines on Management of Hepatitis B Virus Infection in Patients receiving Chemotherapy, Biologicals, Immunosupressants, or Corticosteroids. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2018;8:403-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Lee R, Vu K, Bell CM, Hicks LK. Screening for hepatitis B surface antigen before chemotherapy: current practice and opportunities for improvement. Curr Oncol. 2010;17:32-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Hwang JP, Fisch MJ, Zhang H, Kallen MA, Routbort MJ, Lal LS, Vierling JM, Suarez-Almazor ME. Low rates of hepatitis B virus screening at the onset of chemotherapy. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8:e32-e39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Wang Y, Luo XM, Yang D, Zhang J, Zhuo HY, Jiang Y. Testing for hepatitis B infection in prospective chemotherapy patients: a retrospective study. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:923-930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Hsu PI, Lai KH, Cheng JS, Kao SS, Li YR, Sun WC, Chen WC, Lin KH, Shin CA, Chiang PH, Li YD, Ou WT, Chen HC, Yu HC. Prevention of acute exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B infection in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy in a hepatitis B virus endemic area. Hepatology. 2015;62:387-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Kohrt HE, Ouyang DL, Keeffe EB. Systematic review: lamivudine prophylaxis for chemotherapy-induced reactivation of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:1003-1016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Huang H, Li X, Zhu J, Ye S, Zhang H, Wang W, Wu X, Peng J, Xu B, Lin Y, Cao Y, Li H, Lin S, Liu Q, Lin T. Entecavir vs lamivudine for prevention of hepatitis B virus reactivation among patients with untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma receiving R-CHOP chemotherapy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:2521-2530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Paul S, Saxena A, Terrin N, Viveiros K, Balk EM, Wong JB. Hepatitis B Virus Reactivation and Prophylaxis During Solid Tumor Chemotherapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:30-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Zhang MY, Zhu GQ, Shi KQ, Zheng JN, Cheng Z, Zou ZL, Huang HH, Chen FY, Zheng MH. Systematic review with network meta-analysis: Comparative efficacy of oral nucleos(t)ide analogues for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced hepatitis B virus reactivation. Oncotarget. 2016;7:30642-30658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Visram A, Chan KK, McGee P, Boro J, Hicks LK, Feld JJ. Poor recognition of risk factors for hepatitis B by physicians prescribing immunosuppressive therapy: a call for universal rather than risk-based screening. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0120749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Hwang JP, Vierling JM, Zelenetz AD, Lackey SC, Loomba R. Hepatitis B virus management to prevent reactivation after chemotherapy: a review. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:2999-3008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Su YC, Lin PC, Yu HC, Wu CC. Antiviral prophylaxis during chemotherapy or immunosuppressive drug therapy to prevent HBV reactivation in patients with resolved HBV infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;74:1111-1119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Buti M, Manzano ML, Morillas RM, García-Retortillo M, Martín L, Prieto M, Gutiérrez ML, Suárez E, Gómez Rubio M, López J, Castillo P, Rodríguez M, Zozaya JM, Simón MA, Morano LE, Calleja JL, Yébenes M, Esteban R. Randomized prospective study evaluating tenofovir disoproxil fumarate prophylaxis against hepatitis B virus reactivation in anti-HBc-positive patients with rituximab-based regimens to treat hematologic malignancies: The Preblin study. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0184550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Hwang JP, Somerfield MR, Alston-Johnson DE, Cryer DR, Feld JJ, Kramer BS, Sabichi AL, Wong SL, Artz AS. Hepatitis B Virus Screening for Patients With Cancer Before Therapy: American Society of Clinical Oncology Provisional Clinical Opinion Update. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2212-2220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Liang R, Lau GK, Kwong YL. Chemotherapy and bone marrow transplantation for cancer patients who are also chronic hepatitis B carriers: a review of the problem. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:394-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |