Published online Jul 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i20.5717

Peer-review started: March 11, 2021

First decision: March 25, 2021

Revised: April 19, 2021

Accepted: May 24, 2021

Article in press: May 24, 2021

Published online: July 16, 2021

Processing time: 118 Days and 6.3 Hours

Primary hepatic actinomycosis is a rare infection that can be clinically confused with hepatic pyogenic abscesses or neoproliferative processes. Only a few cases of primary hepatic actinomycosis in children have been reported in the English literature.

We describe a pediatric patient with primary hepatic actinomycosis that involved the base of the right lung and anterior abdominal wall and skin. The patient was diagnosed via histological examination of spontaneously drained material. The patient was successfully treated with an exploratory laparotomy and right posterior segmentectomy of the liver, combined with antibiotic treatment. Following surgery, the patient remains in excellent condition, without evidence of recurrence at the time of drafting this report. To summarize the clinical manifestations, diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes of primary hepatic actinomycosis, 18 case reports in English were reviewed.

We conclude that actinomycosis clinically features a chronic onset, nonspecific symptoms, and a primarily histologic diagnosis. Prolonged antibiotic treatment combined with invasive intervention provides a good prognosis.

Core Tip: Actinomyces are considered natural commensals in the gastrointestinal tract and seldom involved in abdominal infection. We present herein a rare pediatric case of primary hepatic actinomycosis that involved a pulmonary abscess and the anterior abdominal wall and skin. In our case, after diagnosis is made histologically, we chose cefoperazone sulbactam as the main antibiotic treatment which eventually led to a good prognosis when combined with invasive intervention. This case highlights the ultimate importance of early suspect on special infection when normal antibiotic treatment failed and proper antibiotic treatment with surgery are essential in successful treatment for actinomycosis.

- Citation: Liang ZJ, Liang JK, Chen YP, Chen Z, Wang Y. Primary liver actinomycosis in a pediatric patient: A case report and literature review. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(20): 5717-5723

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i20/5717.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i20.5717

Most liver abscesses in children are pyogenic in nature, and amoebic liver abscesses account for 80% of liver abscess cases[1]. Staphylococcus is the leading cause of pyogenic liver abscesses in most cases[1]. Actinomyces are natural commensals in the oral cavity and upper gastrointestinal tract[2]. Primary hepatic actinomycosis is a very rare condition that can clinically be confused with hepatic abscesses or neoproliferative processes[3-5]. Only a few pediatric cases of primary hepatic actinomycosis have been previously reported in the English literature. We describe a pediatric case of primary hepatic actinomycosis that involved a pulmonary abscess and the anterior abdominal wall and skin. We also reviewed previously reported cases of hepatic actinomycosis to emphasize the importance of surgery in its diagnosis and treatment.

A 9-year-old Chinese girl presented to our hospital in April 2017. She complained of cough and recurrent fever of 38 °C-39 °C during the previous month.

The patient's symptoms started 1 mo previous with recurrent fever.

She was diagnosed with an upper respiratory tract infection and treated with antipyretic drugs. However, she showed no improvement after 4 wk of treatment. We discovered a mass in the right upper abdomen and right chest during the last 4 d of the treatment. We recorded her detailed history, but no significant medical history or predisposing factors were noted.

The parents deny any family history of infectious diseases.

Physical examination revealed a large mass involving both the lower part of the right chest and right upper abdomen, with obvious tenderness in the liver; the respiratory sounds in the right side were weaker than those in the contralateral side.

Laboratory investigation revealed a white blood cell count (WBC) of 24.5/nL (normal range: 4-10/nL), neutrophil 82%, hemoglobin 70 g/L (normal range: 120-160 g/L), hematocrit 24.6%, C-reactive protein (CRP) 177 mg/L (normal range: < 10 mg/L). Alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, gamma-glutamyl-transpe

Computed tomography (CT) of her chest revealed a patchy shadow with blurred edges, uneven density in the lower region of the right lung, and thickening of the pleura and chest wall with indistinct intercostal muscles. CT of the abdomen with intravenous contrast revealed a hypodense nonhomogeneous solid lesion (5.2 cm × 7.2 cm × 5.5 cm) in the right lobe of the liver, with obvious enhancement (Figure 1).

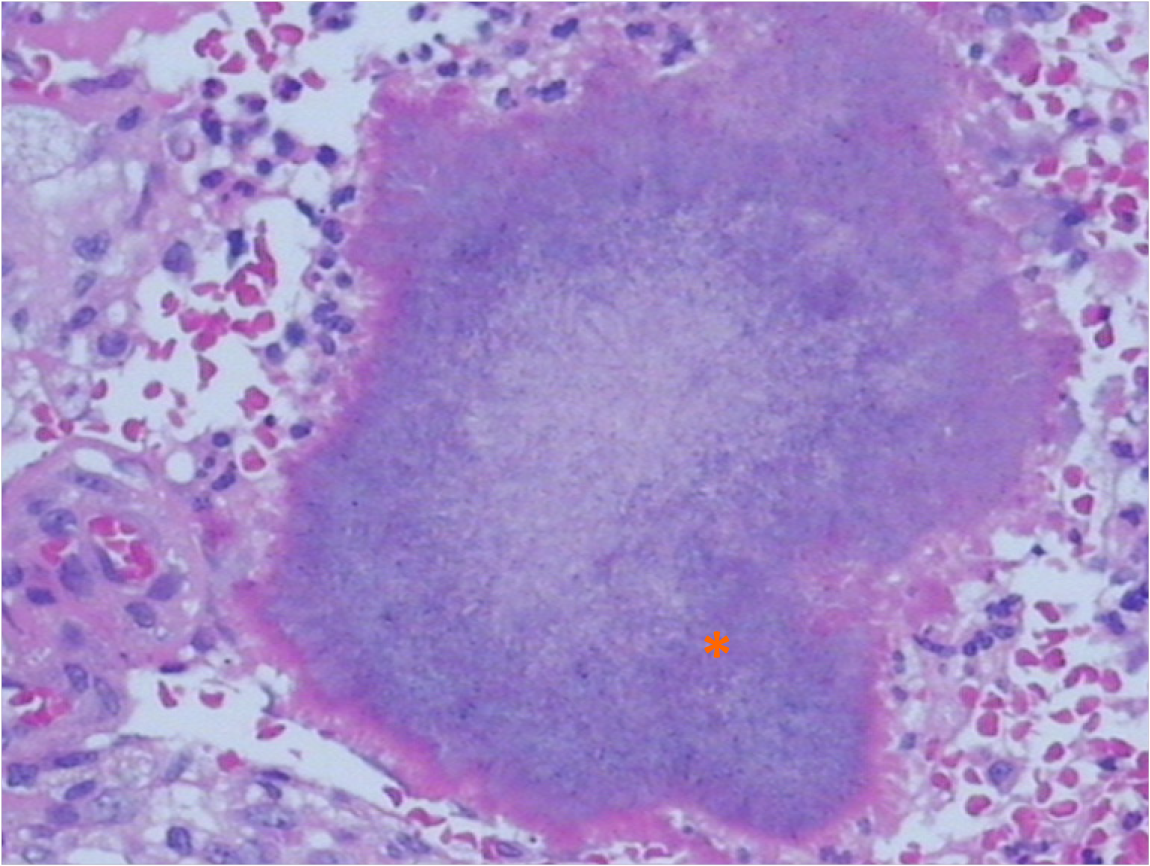

Although the patient's medical history and imaging results indicated an infection, we could not exclude the possibility of malignancy due to the tendency toward invasion and elevated level of CA-125. Therefore, we performed a bone marrow aspiration to exclude any pediatric malignancy, but the results were negative. An ultrasound-guided fine-needle biopsy of the lesion was performed to confirm the diagnosis and causative pathogen. While awaiting the pathological results, the patient was prescribed cefoperazone sodium and sulbactam sodium (intravenous drip; q12h; 50 mg/kg) for 2 wk. During the treatment, the symptoms gradually relieved, and laboratory examinations such as WBC and CRP showed declined levels, supporting the diagnosis of an infectious disease. One week later, pathological histology demonstrated a necrotic lesion in the liver tissue with an infiltration of macrophages and granulocytes, sulfur granules, and gram-positive filamentous bacteria forming radiating aggregates (Figure 2).

The final diagnosis of the presented case is spontaneous liver abscess due to Actinomyces.

Typical histological features confirmed the infection of Actinomyces. However, both biopsy and blood culture were negative, even after culturing the pathogen for 2 wk. The patient continued treatment with cefoperazone sodium and sulbactam sodium because her condition was improving, despite the fact that cefoperazone sodium and sulbactam sodium are not typically the first-line of anti-Actinomyces treatment. After 4 wk of intravenous antibiotic therapy, her CRP level reduced to 14.7 mg/L, and the WBC count was 12.6/nL. The patient was discharged with a prescription of oral antibiotics. During follow-ups over the next 3 mo, the patient's symptoms were relieved and both CRP level and WBC were within the normal ranges. However, CT scan showed no reduction in the size of the liver abscess, although pleural effusion was totally reabsorbed. To evaluate the chest condition, we consulted a respiratory specialist, who performed a bronchofibroscopy and found no focus in the chest. Subsequently, we performed a partial hepatectomy to fully eliminate the infected lesion.

The patient was discharged at 7 d following the successful surgery and was prescribed oral antibiotics for 1 year. At the time of drafting this report, she had no discomfort, and no signs of recurrence were noted during the recent follow-up.

Liver involvement in actinomycosis is relatively rare, accounting for 5% of all actinomycosis and 15% of all abdominal actinomycosis cases[6,7]. Development of hepatic actinomycosis is usually secondary because the liver plays a significant role in abdominal organ drainage. Primary hepatic actinomycosis is believed to occur directly or hematogenically (portal vein or hepatic artery) from an intraabdominal focus, although the source of the infection cannot be located[3,8]. In this article, we have reported a pediatric case of primary liver actinomycosis and reviewed 18 case reports of primary hepatic actinomycosis. The previously reported cases included patients aged 20-86 years, indicating that this is the first report of primary hepatic actinomycosis in a pediatric patient (Tables 1 and 2). The majority of patients (84%, 16/19) were males; all female patients[4,5,8] were aged > 40 years.

| Ref. | Age (yr) | Sex | Manifestation | Involved segment | Diagnostic methods | Antibiotics and total duration |

| Yang et al[12] | 55 | M | UAP, LW | S2, S3 and S4 | Left lobe resection/histology | PG, 4 wk |

| Eve[19] | 60 | M | UAP | UN | Autopsy/histology | UN |

| Zeng et al[11] | 38 | M | UAP, fever | Left lobe | Hepatectomy/histology | Cefoperazone, 7 d |

| Vargas et al[20] | 64 | M | UAP, anorexia, LW | S2, S3 | Hepatectomy/histology | ACA, 6 mo |

| Miyamoto and Fang[23] | 30 | M | Fever, Chills, headache | Right lobe | Percutaneous drainage/pathogen | PG, Clindamycin, Doxycycline, 3 mo |

| Felekouras et al[2] | 53 | M | Fever, Chills | Right lobe | Right posterior segmentectomy/histology | Ciprofloxacin, 6 wk |

| Lange et al[5] | 73 | F | Fever, UAP, LW | S7, S8 | Biopsy guided by US/histology | Amoxicillin, 9 mo |

| Kanellopoulou et al[16] | 70 | M | Fever, LW, anorexia | Multifocal | Biopsy guided by US/histology | AS + oral Amoxicillin, 2 wk |

| Yamada et al[13] | 20 | M | Fever, UAP | Right lobe | Hepatectomy/histology | Erythromycin, chlortetracycline, sulfonamide and streptomycin, duration not mentioned |

| Ref. | Age (yr) | Sex | Manifestation | Involved segment | Diagnostic methods | Antibiotics and total duration |

| Culafić et al[4] | 50 | F | Fever, UAP, LW | Right lobe | Hepatectomy/histology | Benzylpenicillin + oral Amoxicillin, 7.5 mo |

| Sugano et al[18] | 86 | M | Fever, anorexia | Right lobe | Biopsy guided by US/histology + pathogen | Minocycline, Piperacillin, Ampicillin, 4 mo |

| Sharma et al[14] | 34 | M | Fever, UAP | Right lobe | Biopsy guided by CT/histology | Clindamycin, Ceftriaxone, 5 mo |

| Wayne et al[17] | 65 | M | Fever | S5, S6 | Hepatectomy/histology | Doxycycline, 6 mo |

| Cetinkaya et al[3] | 40 | M | UAP, LW | Multifocal (right + left lobe) | Drainage/histology | PG, 3 mo |

| Kasano et al[6] | 41 | M | UAP | Right lobe | Surgery/histology | UN |

| Ha et al[15] | 57 | M | No symptom | Multifocal | Laparotomy biopsy/histology | PG, Ceftriaxone + oral Amoxicillin, 17 wk |

| Wong et al[21] | Case 1 46/Case 2 59 | M/M | Fever/UAP | Multifocal/right lobe | Drainage/pathogen | PG, duration not mentioned |

| Kocabay et al[8] | 40 | F | Fever, LW, fatigue | S7, S8 | Hepatectomy/histology | PG + oral Amoxicillin, 7.5 mo |

| Our case | 9 | F | Fever, LW, abdominal mass | Right lobe | Histology | Cefoperazone sodium and sulbactam sodium, 4 wk, + oral Amoxicillin, 1 yr |

Actinomycosis clinically features a chronic onset with nonspecific symptoms, contributing to a difficulty in diagnosis. It typically takes 1-3 mo before patients present to a clinic for further investigation. Fever, weight loss, and anemia, which are nonspecific symptoms and provide little information for a differential diagnosis, are the most common complaints[9]. The immune condition of the host in human actinomycosis has been controversial in international literature. Because most reported cases did not have any immunosuppressive or possibly predisposing factors, the attention has been focused on trying to determine the nature of the initial pathological factor leading to the transformation of normal flora into an invasive pathogen.

One explanation may be attributed to multipathogen infections. It has been reported that approximately 60%-90% of actinomycosis infections are caused by multiple bacterial flora, of which the most commonly isolated were Bacteroides, Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Enterococcus, or Pseudomonas[10]. In our literature review, 43% (3/7) of patients with a positive etiology were infected by multiple pathogens, such as Streptococcus milleri, Fusobacterium nucleatum, and Proteus mirabilis. Multipathogen infections may be important in the invasion process; for instance, in the liver, which is an oxygen-rich organ, anaerobic actinomycosis may initiate the invasion process, based on the anoxic microenvironment and lead by aerobic bacteria[11]. Our patient presented with fever and weight loss without immunosuppression factors; thus, it was confusing whether the patient had an infection or showed signs of malignancy. Therefore, we performed a biopsy and made a histologic diagnosis. This is a common challenge in actinomycosis cases because 13/19 cases were suspected to be malignant, and biopsy or surgery were performed to obtain the final diagnosis, leading to a prolonged admission period and higher costs.

An appropriate diagnosis can be confirmed as soon as the histological or cytological evidence is confirmed. However, histological diagnosis is more frequent than cytological diagnosis because 89% (17/19) of cases in this review were histologically diagnosed[2-6,8,11-20], whereas none of the cases successfully isolated Actinomyces. Furthermore, none of the blood cultures were positive with Actinomyces. This may be attributed to the fact that Actinomyces species require a prolonged period of strict anaerobic conditions to grow, whereas typical microscopic findings are more accessible in laboratory settings. Moreover, previous antibiotic therapy may be responsible for a negative result.

Appropriate antibiotic therapy is fundamental in the treatment of actinomycosis; however, the traditional treatment duration has been facing a number of challenges recently. Traditional opinions insisted that prolonged administration (6-12 mo) and high doses (to facilitate drug penetration in the abscess and in infected tissues) of penicillin G or amoxicillin should be the first choice of treatment, providing a good prognosis[5,11,21]. However, Lange et al[5] also reported a case exhibiting drug resistance after prolonged therapy reminding surgeons to attempt to shorten the duration of antibiotic treatment as much as possible to avoid drug resistance. In addition, two cases also demonstrated that a relatively short treatment course can still result in a successful outcome. Valour et al[22] demonstrated that the duration of antimicrobial therapy could likely be shortened to 3 mo in patients who have undergone optimal surgical resection of infected tissues was performed. In a case with a small focus in the left lobe of the liver, even 7 d of intravenous cefoperazone with surgical resection led to a good result[11]. In a polymicrobial case, antibiotic therapy should include agents with efficient antibiotic activity against the associated pathogens[14]. In our case, through successful partial hepatectomy and a 3-mo antibiotic regimen, the patient recovered fully and showed no recurrence on ultrasound scanning during follow-up.

In conclusion, primary hepatic actinomycosis is rare and has been reported sporadically. Actinomycosis clinically features a chronic onset and nonspecific symptoms; its diagnosis is primarily histologic. Prolonged antibiotic treatment combined with invasive intervention are the first treatment options that provide a good prognosis.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gonoi W S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Waghmare M, Shah H, Tiwari C, Khedkar K, Gandhi S. Management of Liver Abscess in Children: Our Experience. Euroasian J Hepatogastroenterol. 2017;7:23-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Felekouras E, Menenakos C, Griniatsos J, Deladetsima I, Kalaxanisi N, Nikiteas N, Papalambros E, Kordossis T, Bastounis E. Liver resection in cases of isolated hepatic actinomycosis: case report and review of the literature. Scand J Infect Dis. 2004;36:535-538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cetinkaya Z, Kocakoc E, Coskun S, Ozercan IH. Primary hepatic actinomycosis. Med Princ Pract. 2010;19:196-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Culafić DM, Lekić NS, Kerkez MD, Mijac DD. Liver actinomycosis mimicking liver tumour. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2009;66:924-927. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lange CM, Hofmann WP, Kriener S, Jacobi V, Welsch C, Just-Nuebling G, Zeuzem S. Primary actinomycosis of the liver mimicking malignancy. Z Gastroenterol. 2009;47:1062-1064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kasano Y, Tanimura H, Yamaue H, Hayashido M, Umano Y. Hepatic actinomycosis infiltrating the diaphragm and right lung. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:2418-2420. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Roesler PJ Jr, Wills JS. Hepatic actinomycosis: CT features. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1986;10:335-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kocabay G, Cagatay A, Eraksoy H, Tiryaki B, Alper A, Calangu S. A case of isolated hepatic actinomycosis causing right pulmonary empyema. Chin Med J (Engl). 2006;119:1133-1135. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Lin K, Lin S, Lin AN, Lin T, Htun ZM, Reddy M. A Rare Thermophilic Bug in Complicated Diverticular Abscess. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2017;11:569-575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Smego RA Jr, Foglia G. Actinomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1255-61; quiz 1262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 359] [Cited by in RCA: 323] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zeng QQ, Zheng XW, Wang QJ, Yu ZP, Zhang QY. Primary hepatic actinomycosis mimicking liver tumour. ANZ J Surg. 2018;88:E629-E630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yang XX, Lin JM, Xu KJ, Wang SQ, Luo TT, Geng XX, Huang RG, Jiang N. Hepatic actinomycosis: report of one case and analysis of 32 previously reported cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16372-16376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yamada T, Sakai A, Tonouchi S, Kawashima K. Actinomycosis of the liver. Report of a case with special reference to liver function tests. Am J Surg. 1971;121:341-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sharma M, Briski LE, Khatib R. Hepatic actinomycosis: an overview of salient features and outcome of therapy. Scand J Infect Dis. 2002;34:386-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ha YJ, An JH, Shim JH, Yu ES, Kim JJ, Ha TY, Lee HC. A case of primary hepatic actinomycosis: an enigmatic inflammatory lesion of the liver. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2015;21:80-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kanellopoulou T, Alexopoulou A, Tiniakos D, Koskinas J, Archimandritis AJ. Primary hepatic actinomycosis mimicking metastatic liver tumor. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:458-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wayne MG, Narang R, Chauhdry A, Steele J. Hepatic actinomycosis mimicking an isolated tumor recurrence. World J Surg Oncol. 2011;9:70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sugano S, Matuda T, Suzuki T, Makino H, Iinuma M, Ishii K, Ohe K, Mogami K. Hepatic actinomycosis: case report and review of the literature in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:672-676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Eve FS. Case of Actinomycosis of the Liver. Br Med J. 1889;1:584-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Vargas C, González C, Pagani W, Torres E, Fas N. Hepatic actinomycosis presenting as liver mass: case report and review of the literature. P R Health Sci J. 1992;11:19-21. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Wong JJ, Kinney TB, Miller FJ, Rivera-Sanfeliz G. Hepatic actinomycotic abscesses: diagnosis and management. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:174-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Valour F, Sénéchal A, Dupieux C, Karsenty J, Lustig S, Breton P, Gleizal A, Boussel L, Laurent F, Braun E, Chidiac C, Ader F, Ferry T. Actinomycosis: etiology, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and management. Infect Drug Resist. 2014;7:183-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 285] [Article Influence: 25.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Miyamoto MI, Fang FC. Pyogenic liver abscess involving Actinomyces: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:303-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |