Published online Jul 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i20.5661

Peer-review started: March 1, 2021

First decision: April 18, 2021

Revised: April 21, 2021

Accepted: April 28, 2021

Article in press: April 28, 2021

Published online: July 16, 2021

Processing time: 128 Days and 7.1 Hours

Extra-hepatic bile duct injury (EHBDI) is very rare among all blunt abdominal injuries. According to literature statistics, it only accounts for 3%-5% of abdominal injuries, most of which are combined injuries. Isolated EHBDI is more rare, with a special injury mechanism, clinical presentation and treatment strategy, so missed diagnosis easily occurs.

We report a case of unexplained abdominal effusion and jaundice following blunt abdominal trauma in our department. Of which, surgical exploration of the case was performed and a large amount of bile leakage in the abdominal cavity was found. No obvious abdominal organ damage or bile duct rupture was found. Surgery was terminated after the common bile duct indwelled with a T tube. After 2 wk, a T-tube angiography revealed the lesion in the common bile duct pancreatic segment, confirming isolated EHBDI. And 2 mo later, the T tube was pulled out with re-examined magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, indicating narrowing of the common bile duct injury, with no special treatment due to no clinical symptoms and no abnormality in the current follow-up.

This case was featured by intraoperative bile leakage and no EHBDI. This type of rare isolated EHBDI is prone to missed and delayed diagnosis due to its atypical clinical manifestations and imaging features. Surgery is still the main treatment, and the indications and principles of bile duct injury repair must be followed.

Core Tip: We report the diagnosis and treatment of a rare case of isolated extra-hepatic bile duct injury (EHBDI). This was a case of unexplained peritoneal bile leakage following abdominal trauma in a patient without severe peritoneal irritation, which led to diagnostic difficulties. In particular, no obvious lesion was found after exploratory examination, so only a T-shaped tube was indwelling in the common bile duct. Isolated EHBDI was confirmed by postoperative T-tube angiography and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, and mild common bile duct stenosis was found at follow-up. We believe this is a rare case that deserves to be summarized. Combined with a literature review, we summarize the injury mechanism, clinical manifestations and treatment strategies of solitary EHBDIs.

- Citation: Zhao J, Dang YL, Lin JM, Hu CH, Yu ZY. Rare isolated extra-hepatic bile duct injury: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(20): 5661-5667

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i20/5661.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i20.5661

Extra-hepatic bile duct injury (EHBDI) is rare among all blunt abdominal injuries. Fizeau[1] first reported the case of common bile duct rupture in 1806. According to current literature statistics, it only accounts for 3%-5% of abdominal injuries[2,3], of which most are combined injuries and 85% are gallbladder injuries. Isolated EHBDI is very rare, with specific injury mechanism, clinical manifestations and treatment strategies, so missed diagnosis easily occurs. We summarize the clinical data and clinical features of a rare case of isolated EHBDI diagnosed and treated in our department in April 2020, combined with a literature review.

A 53-year-old male complained of blunt trauma to the chest and abdomen due to a fall 6 mo prior.

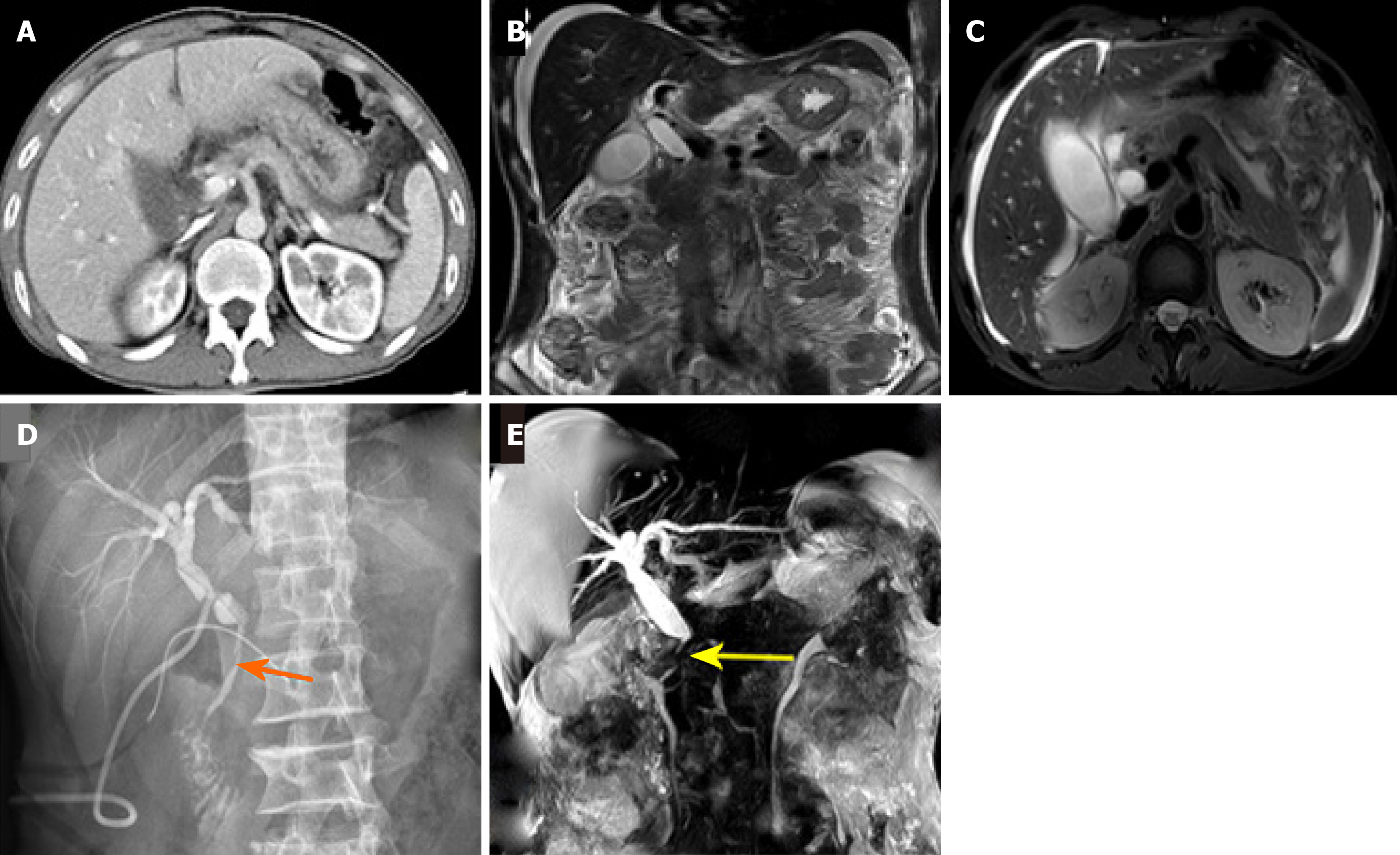

The patient suffered severe chest and abdominal pain immediately after the injury and was immediately sent to the local hospital. The diagnosis was "closed chest and abdomen trauma, lumbar spine fracture, rib fracture," without evidence of abdominal organ injury. After conservative treatment, the pain gradually subsided. Abdominal computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging reexamination were conducted 6 mo after the injury (Figure 1A-C), revealing a large amount of fluid in the abdomen, pelvic cavity and around the liver, which was indicative of liver contusion, so he was transferred to our hospital for further treatment.

He was in good health, without history of trauma or surgery.

No familial genetic diseases.

At the time of admission, the patient’s mental, sleep, diet, and physical strength were normal, as well as urine and feces, without weight loss. Physical examination: Stable vital signs, slightly yellow skin and sclera, and rough breathing sounds in both lungs; abdominal distension, no gastrointestinal pattern and peristaltic wave, obvious abdominal tenderness accompanied by slight rebound pain, no muscle tension, no abdominal mass touch; negative murphy sign, no percussion pain in the liver area, and no shifting dullness; and weak intestinal sounds of 2-3 times/min, and light yellow bile fluid extracted by diagnostic abdominal puncture.

Blood routine examination reported that white blood cell and n (%) were normal. Liver function test showed that total bilirubin 66.4 μmol/L, albumin 32.3 g/L, alanine aminotransferase 46 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase 28 U/L, r-GT 420 U/L, and amylase 63 U/L. Infection indicator indicated that procalcitonin 0.20 ng/mL and C-reactive protein 76 mg/L. Coagulation function suggested that prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, and international normalized ratio were normal.

Zhi-Yong Yu, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery, The Affiliated Hospital of Yunnan University, and Shi-Zhe Yu, Department of Organ Transplant Surgery, The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, participated in the consultation together. For suspected bile duct injury, diagnosis and treatment were recommended to confirm through exploratory laparotomy.

At 2 wk after surgery, the T-tube angiography (Figure 1D) showed that the common bile duct was intact, without leakage of contrast agent, with the injury located in the pancreatic segment of the common bile duct, which was dilated above the injury plane. Therefore, it was confirmed to be a solitary EHBDI.

During surgery, large accumulation of bile accumulation was observed in the abdominal cavity (approximately 1000 mL), with no damage in the liver. Careful examination of the gallbladder and extra-hepatic bile ducts (left and right hepatic ducts, hepatic duct, and common bile duct) found no obvious damage but common bile duct dilatation about 1.2 cm. After abdominal cavity cleaning, an 18F T tube in the common bile duct was indwelling for external bile drainage, and surgery was completed.

The patient recovered smoothly without complications after surgery. T tube was clamped and discharged from the hospital 2 wk after surgery, and then the T tube was removed and the magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography was reviewed (Figure 1E), indicating the narrow injury site of the lower part of the common bile duct. Considering that the patient had no obvious discomfort symptoms and no obstructive jaundice, no treatment was given. At present, no abnormalities were found in the follow-up.

Isolated EHBDI is rare in clinical practice, and has rarely been reported in the literature. The author retrieved 204 studies involving EHBDI in the last 10 years from PubMed, of which only 23 were about isolated EHBDI, most of which were case reports that were mostly combined with injuries, only 1 systematic review[4] and 2 summaries of complications[5,6]. A study involving 1873 patients with blunt abdominal injuries reported only 7 cases of EHBDI[6]. Few cases have been reported in domestic literature, among which, Xijing Hospital summarized 280 cases of abdominal trauma, including 6 cases of EHBDI, combined with other organ injuries[7]. Thus, isolated EHBDI is a small probability event that is easily overridden by other combined damage and ignored.

The damage mechanism of isolated EHBDI is unique, which mainly results from a sudden increase in abdominal pressure or sudden deceleration caused by liver injury or compression displacement injury, and generates a “shear force” at relatively fixed locations of bile duct, such as the entrance to the choledochospancreas (about 23%), the beginning of the left hepatic duct(about 26%), and the suprapancreatic common bile duct (about 32%), leading to bile duct avulsion[4,8].

The clinical manifestations of isolated EHBDI are not specific and vary greatly with the types of injury, including the following. (1) Non-full-thickness bile duct contusion. The bile duct of this type has complete continuity, which only presents as abdominal pain without bile leakage. No bile can be seen during abdominal puncture or lavage. (2) Simple bile duct laceration, whose wound length is less than tangential wound 1/2 the circumferential diameter of the duct wall. The patients of this type may have bile leakage in the early stage, but missed diagnosis easily occurs due to small trauma and easy self-limiting, small chemical stimulation of unconcentrated bile, early limited encapsulation and other factors, resulting in short duration, delay or atypical symptoms. And (3) Complex bile duct laceration. This type includes tangential injury with a length greater than 1/2 the circumferential diameter of the duct wall, segmental defect of the bile duct wall, and complete penetration of the bile duct. It is often manifested as prolonged and extensive biliary leakage, but is easily confused with biliary leakage and peritoneal effusion caused by liver and duodenal injury.

Preoperative diagnosis of isolated EHBDI is very difficult, without typical imaging signs, and abdominal effusion, intestinal dilatation, organ injury and vascular combined injuries interfere with the imaging evaluation and determination of the injury site. New diagnostic methods, such as technetium-99 radionuclide scanning, have certain diagnostic value[7], and preoperative or intraoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) can help clarify the diagnosis[9,10]. Bile leakage is a common clinical manifestation, lacking specificity. Abdominal pain is present in most but not all cases, and large biliary leakage without obvious biliary peritonitis is rare. Limitations of imaging diagnosis and atypical clinical manifestations often lead to delayed diagnosis. According to the literature, the mean time to diagnosis is 11 d after injury[4], and most diagnoses can still be confirmed by surgical exploration and intraoperative cholangiography[11]. Surgeons need to pay attention to the possibility of EHBDI during surgery, and careful and comprehensive intraoperative exploration of extra-hepatic bile duct, especially intrapancreatic common bile duct injury (accounting for about 1/4 of isolated EHBDIs)[4] is very likely to be omitted, which should be paid enough attention. However, even so, the probability of EHBDI being diagnosed by initial surgical exploration is still less than 60%[4].

Surgical treatment remains the primary treatment for isolated EHBDI, while conservative treatment is associated with higher risk[11]; both of them can be divided into early treatment, delayed treatment, and late treatment. Early treatment is mainly damage controlled surgery[12] including exploration, immediate repair, and patency drainage. The whole extra-hepatic bile duct tree should be included in the exploration, especially the intrapancreatic common bile duct. At this time, the descending part of the head of pancreas and duodenum should be turned over by the Kocher incision, and sometimes the posterior superior pancreaticoduodenal vein/posterior superior pancreaticoduodenal artery should be dissected and completely exposed. Second, consideration should be given to the possibility of vascular injury, which may lead to necrosis and stenosis of the bile ducts. In the repair of bile duct, the degree of injury should be considered. When the diameter of the injury is less than 1/2 the injury, and the surrounding inflammation and edema are not serious, immediate repair can be considered; in the case of severe injury and inflammation or poor general condition, appropriate debridement and adequate drainage after the plastic bile duct can be considered for secondary repair. T tube is very important as the endoluminal support tube, not only to keep the bile duct drainage patency, but more importantly, to preserve the channel for postoperative cholangiography to evaluate bile duct stenosis, which is also important to place abdominal drainage tube and moderate negative pressure suction. Delayed treatment mainly refers to definite bile duct repair surgery. The timing of repair is controversial, with ranges ranging from 3 d to 6 wk in the literature[12], but there is a consensus that early completion of a definite procedure results in a better prognosis. According to the summary of the experience of General Hospital of Chengdu Military Region[13], the corresponding surgeries were performed according to the size of the circumferential diameter of bile duct injury, such as direct plastic repair, pedicled gallbladder flap or pedicled stomach or jejunal flap for bile duct repair, portal bile duct plastic repair and Roux-Y bilio enterostomy. The author suggests that maintaining a good blood supply, no tension and reducing bile leakage are necessary conditions for good prognosis after repair, and the length of injury is also one of the indicators that must be paid attention to. The ones less than 2 cm can be directly repaired; biliary duct resection and end-to-end anastomosis (without affecting blood supply) or choledoenterostomy may be chosen according to the surgeon's experience in patients with injuries greater than 2 cm and with wider ring diameter or complete fracture. Minimizing biliary and intestinal anastomosis is beneficial to prevent postoperative reflux and improve the quality of life. However, the long-term effects of end-to-end anastomosis still need to be observed, so this surgery is controversial[14]. Late treatment is mainly for bile duct stenosis, which has a reported incidence of about 10%[15], as a late complication of bile duct injury that is mostly caused by improper early treatment. In this treatment, the stenosis length, location, blood supply, local inflammation and other conditions should be adequately evaluated and eventually repaired. Balloon dilation and biliary stent implantation under ERCP have advantages as a new minimally invasive method for the treatment of bile duct stenosis[10,16], but they need to be performed in collaboration with standardized multidisciplinary therapy.

Summing up the treatment experience of this case, there are still places worth reflecting on. In terms of etiology, it accords with the pathogenic features of isolated EHBDI. The clinical manifestations were consistent with simple bile duct laceration, showing early abdominal pain and abdominal and pelvic bile accumulation only, without obvious signs of biliary peritonitis and abdominal infection. Imaging examination failed to indicate the injury and site, leading to a delay in diagnosis. However preoperative diagnosis did not consider the possibility of EHBDI. Although the entire extra-hepatic bile duct was explored, no lesion site was found, with no intraoperative cholangiography, which was a deficiency. It has been noted that nonoperative treatment is possible when the only relative indication of surgery is bile leakage[11]. Can this patient be cured by abdominal puncture and drainage in combination with conservative treatment? The author believes that the premise of conservative treatment is able to make a clear diagnosis in advance, otherwise misdiagnosis and missed diagnosis will cost painfully. Can ERCP be diagnosed early preoperatively? Can EHBDI with minor injury be cured by ERCP+ biliary stent drainage? To date, such successful treatments are rare[10,16], but worth a try. In such cases of negative intraoperative exploration and dilatation of common bile duct, it is advisable to conduct external drainage of common bile duct by T tube placement only based on the symptoms of common bile leakage. Postoperative angiography further clarified the site of injury and also left room for subsequent treatment.

Isolated EHBDI is extremely rare in clinical practice and is easily overlooked and missed, with special and complicated clinical features. Therefore, when blunt abdominal trauma, especially residual bile, is found in the abdominal cavity, high vigilance should be given to the presence of EHBDI, and intraoperative cholangiography should be performed when such suspicion is doubt to avoid adverse consequences caused by diagnostic errors. Surgical treatment should follow the repair evidence and strategy of BDI, maintain the physiological structure and function of bile duct, and reduce the probability of postoperative bile duct stenosis.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: International Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Society China Branch; Liver Cancer Professional Committee of Yunnan Medical Doctor Association; and Biliary Carcinoma Professional Committee of Yunnan Anticancer Association.

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Zyoud SH S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Ishida T, Hayashi E, Tojima Y, Sakakibara M. Rupture of the common bile duct due to blunt trauma, presenting difficulty in diagnosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Huang ZQ. Huang zhiqiang biliary surgery, 1st Ed. Jinan: Shandong Science and Technology Press, 2000: 478-479. |

| 3. | Posner MC, Moore EE. Extrahepatic biliary tract injury: operative management plan. J Trauma. 1985;25:833-837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Pereira R, Vo T, Slater K. Extrahepatic bile duct injury in blunt trauma: A systematic review. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019;86:896-901. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kitagawa S, Hirayama A. Bile Duct Stricture After Blunt Abdominal Trauma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rodriguez-Montes JA, Rojo E, Martín LG. Complications following repair of extrahepatic bile duct injuries after blunt abdominal trauma. World J Surg. 2001;25:1313-1316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gao ZQ, You N, Liu WH. Diagnosis and treatment of traumatic bile duct injury. Gandanyi Waike Zazhi. 2011;23:267-268. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Balzarotti R, Cimbanassi S, Chiara O, Zabbialini G, Smadja C. Isolated extrahepatic bile duct rupture: a rare consequence of blunt abdominal trauma. Case report and review of the literature. World J Emerg Surg. 2012;7:16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mandal N, Mandal R, Ranjan R. Complete transection of common bile duct after blunt trauma abdomen--a case report. J Indian Med Assoc. 2013;111:560-561. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Arun S, Santhosh S, Sood A, Bhattacharya A, Mittal BR. Added value of SPECT/CT over planar Tc-99m mebrofenin hepatobiliary scintigraphy in the evaluation of bile leaks. Nucl Med Commun. 2013;34:459-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Poli ML, Lefebvre F, Ludot H, Bouche-Pillon MA, Daoud S, Tiefin G. Nonoperative management of biliary tract fistulas after blunt abdominal trauma in a child. J Pediatr Surg. 1995;30:1719-1721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Liang LJ. The main points of repair and restenosis after repair of iatrogenic bile duct injury. Zhongguo Shiyong Waike Zazhi. 2018;38:1014-1017. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Jiang ZX, Dai RW, Tian FZ, Yang SJ, Liu YL. Injury control surgery for extrahepatic bile duct trauma (report of 15 cases). Zhongguo Puwaijichuyulinchuang Zazhi. 2008;15:508-510. |

| 14. | Strasberg SM, Helton WS. An analytical review of vasculobiliary injury in laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy. HPB (Oxford). 2011;13:1-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Parks RW, Diamond T. Non-surgical trauma to the extrahepatic biliary tract. Br J Surg. 1995;82:1303-1310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kibria R, Barde CJ, Ali SA. Successful primary endoscopic treatment of suprapancreatic biliary stricture after blunt abdominal trauma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:186-187; discussion 187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |