Published online Jul 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i19.5325

Peer-review started: February 26, 2021

First decision: March 27, 2021

Revised: April 2, 2021

Accepted: May 20, 2021

Article in press: May 20, 2021

Published online: July 6, 2021

Processing time: 117 Days and 8.1 Hours

Anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) antibody is known to cause several autoimmune-related situations. The most known relationship is that it may cause type I diabetes. In addition, it was also reported to result in several neurologic syndromes including stiff person syndrome, cerebellar ataxia, and autoimmune encephalitis. Decades ago, isolated epilepsy associated with anti-GAD antibody was first reported. Recently, the association between temporal lobe epilepsy and anti-GAD antibody has been discussed. Currently, with improvements in exami

A 44-year-old female Asian with a history of end-stage renal disease (without diabetes mellitus) under hemodialysis presented with diffuse abdominal pain. The initial diagnosis was peritonitis complicated with sepsis and paralytic ileus. Her peritonitis was treated and she recovered well, but seizure attack was noticed during hospitalization. The clinical impression was gelastic seizure with the presentation of frequent smiling, head turned to the right side, and eyes staring without focus; the duration was about 5–10 s. Temporal lobe epilepsy was recorded through electroencephalogram, and she was later diagnosed with anti-GAD65 antibody positive autoimmune encephalitis. Her seizure was treated initially with several anticonvulsants but with poor response. However, she showed excellent response to intravenous methylprednisolone pulse therapy. Her consciousness returned to normal, and no more seizures were recorded after 5 d of intravenous methylprednisolone treatment.

In any case presenting with new-onset epilepsy, in addition to performing routine brain imaging to exclude structural lesion and cerebrospinal fluid studies to exclude common etiologies of infection and inflammation, checking the auto

Core Tip: This case reminds us that autoimmune encephalitis is a diagnosis that should not be missed when we encountering a patient presenting with new-onset seizure. Gelastic seizure could be a rare presentation of glutamic acid decarboxylase 65-positive autoimmune encephalitis.

- Citation: Yang CY, Tsai ST. Glutamic acid decarboxylase 65-positive autoimmune encephalitis presenting with gelastic seizure, responsive to steroid: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(19): 5325-5331

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i19/5325.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i19.5325

Anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 (GAD65) antibody-related neurologic disorders have been frequently reported worldwide and are clinically heterogeneous and difficult to diagnose. The main neurologic syndromes reported to be related to anti-GAD65 antibody include stiff-person syndrome, cerebellar ataxia, and limbic encephalitis. Besides these syndromes, progressive encephalomyelitis with rigidity and myoclonus[1], myelitis[2], palatal myoclonus[3], opsoclonus-myoclonus[4], and auto

A 44-year-old woman presented to the Emergency Department with diffuse abdominal pain for 2 d and had a seizure attack during her stay at our hospital.

The patient received peritoneal dialysis for years as a treatment for end-stage renal disease and recently shifted to hemodialysis due to frequent peritonitis. This time, she initially came to the Emergency Department due to diffuse abdominal pain for 2 d, and she was initially treated as peritonitis. She recovered well from the peritonitis with relatively stable condition. Later during her stay at the intensive care unit, an acute onset of consciousness disturbance was observed by the nurse practitioner. A neurologist was therefore consulted for further evaluation. Frequent smiling, head turned to the right side, and eyes staring without focus were observed and recorded by video (Video 1).

The patient had been diagnosed with end-stage renal disease and received peritoneal dialysis possibly due to malignant hypertension; recently, she was shifted to hemodialysis. She did not have type I diabetes mellitus; the most recent hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) was 4.9% (normal upper limit is 6.0%).

The patient does not drink alcohol or take any illicit drugs, and her family history is unremarkable in her situation. None of her family members have epilepsy, diabetes mellitus, autoimmune disease, or cancer.

Upon consultation, her Glasgow Coma Scale score was 13 (eyes open 4, verbal 4, movement 5), with no obvious weakness over the limbs nor gaze deviation or limitation. She was not able to cooperate with neurologic examination well due to impaired consciousness, and high cortical dysfunction due to underlying disease was highly suspected. Few episodes of clinical seizure attack were observed during examination, with sudden loss of awareness, head turning toward the right side, and eyes rightward gazing with smiling expression, with a duration of about 5–10 s.

Cerebrospinal fluid studies showed normal white blood cell and micro-protein levels (white blood cell count: 0/μL; micro-protein: 50.0 mg/dL; glucose: 57 mg/dL)

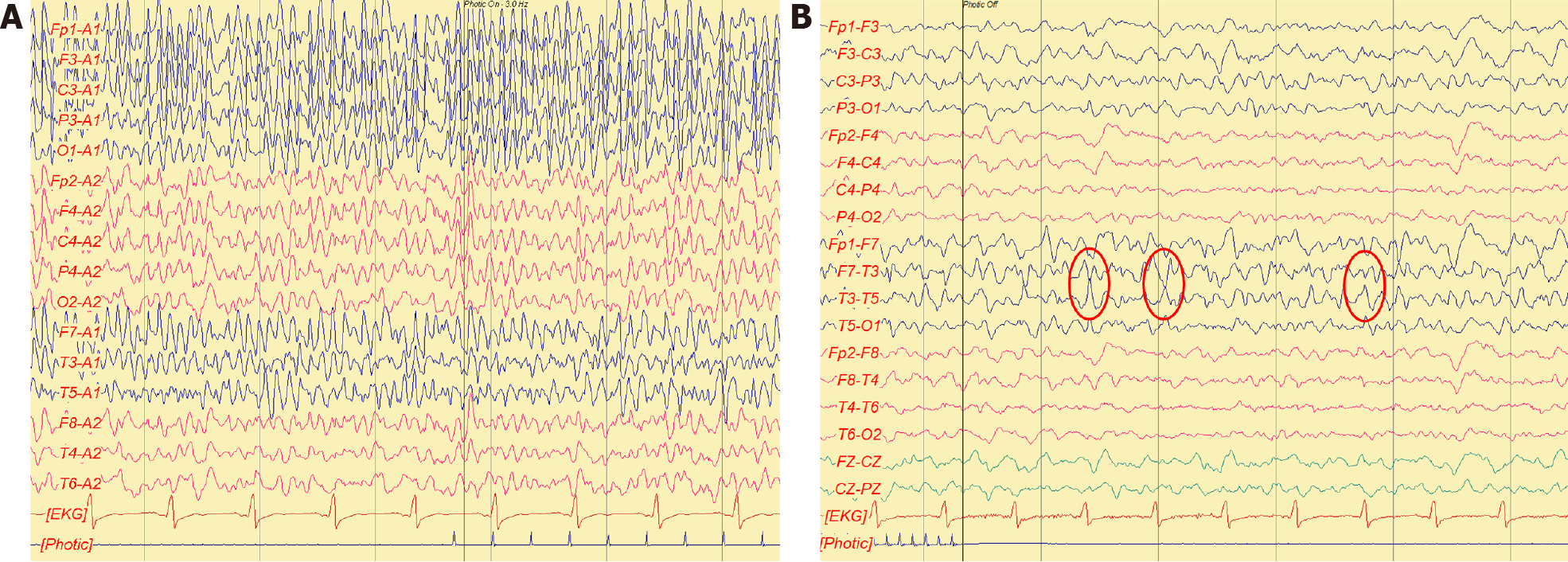

Awake electroencephalogram (EEG) showed evidence of seizure attack with possible temporal lobe origin (Figure 1).

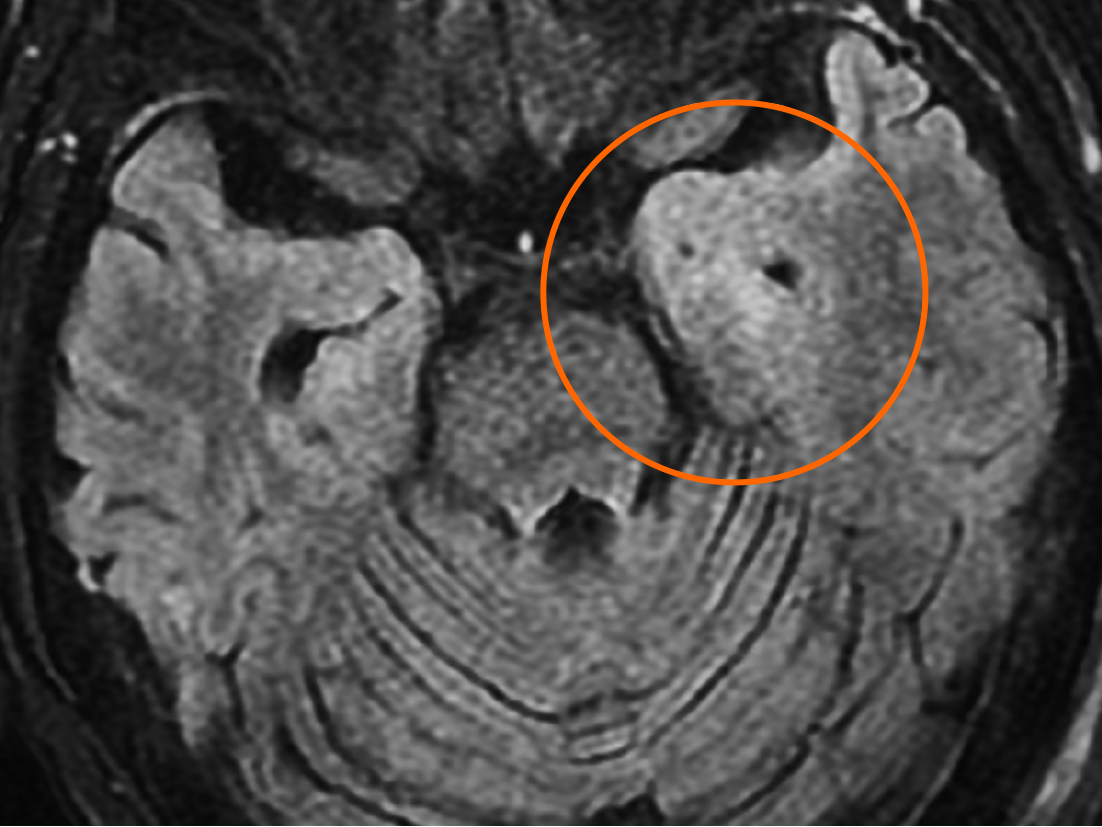

Brain magnetic resonance imaging revealed hyperintensity in the bilateral mesial temporal cortex in T2 weighted image and T2 fluid-attenuated inversion recovery series, more prominent in the left side, without contrast enhancement (Figure 2).

She was first admitted to the general ward, treated with ertapenem, and stabilized on hospital day 4. However, generalized tonic-clonic seizures associated with respiratory failure occurred several times; the patient was then intubated and transferred to the intensive care unit. Drug-induced seizure was highly suspected, so the antibiotic was shifted to ceftriaxone. Levetiracetam was administrated for seizure prevention initially, and later valproic acid was also used. The patient regained consciousness 1 d later, and under relatively stable condition, she was extubated. There were no more generalized tonic-clonic seizure attacks, but occasional speech disturbance and frequent loss of consciousness with the duration of a few seconds were observed by the nurse practitioner. A neurologist was consulted for evaluation about the bizarre presentation. Upon visiting, she could partially obey simple orders, and her intermittent smiling, neck turned to the right side, and eyes gazing rightward were noticeable. The impression was gelastic seizure with frequent attacks. Awake EEG was performed and showed evidence of epilepsy, with focal onset seizure from the left temporal area, with a total of 34 events in the first recording day. Subsequent brain magnetic resonance imaging revealed hyperintensity in the bilateral mesial temporal cortex, more prominent in the left side. Lumbar puncture showed no pleocytosis (white blood cell: 0/μL) and mild elevated micro-protein (50 mg/dL). The impression was autoimmune or viral encephalitis.

A neurologist was consulted for consciousness disturbance. Clinical seizure was observed and was proven by EEG.

Anti-GAD65-positive autoimmune encephalitis presented with gelastic epilepsy.

Acyclovir was prescribed as the antiviral agent, and intravenous methylprednisolone (IVMP) 1000 mg/d was started as pulse therapy. Seizure was still observed by both clinical observation and 24-h long-term EEG. Frequent seizure attacks were recorded with a maximum attack number of up to 34 times per day, each time with a similar clinical presentation that lasted for 2–3 min. Epileptiform discharges were still noticed, even after oxcarbazepine was added (with previous levetiracetam and valproic acid) but dramatically reduced and later disappeared after the second dose of methylprednisolone and the first dose of intravenous lacosamide. After 5 d of pulse therapy, steroid was shifted to oral form. No more seizure attacks were observed, and our patient’s consciousness was back to normal. During hospitalization, several laboratory examinations were reviewed to assess for the etiology, including autoimmune profile and limbic encephalitis kit [N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor, α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid receptor (commonly known as NMDA), contactin-associated protein-like 2 (commonly known as CASPR2), leucine-rich glioma inacti

The patient became alert and oriented 1 d after the steroid pulse therapy. Seizure attack was no longer observed during admission. On the day 20 of hospitalization, the patient was discharged and was able to go back to her workplace without difficulty. Low-dosage steroid of prednisolone 10 mg/d was prescribed for 2 mo, titrating down the dosage to 5 mg/d for 2 mo and then discontinued. Lacosamide 200 mg daily was used for 1 mo and then 100 mg daily for 4 mo. No further recurrence and no cognitive impairment was experienced, and she was able to do all her activities of daily living and even her job without any difficulty. No evidence of cancer was observed during follow-up (14 mo till now).

Seizure is an easily encountered situation during daily practice in the hospital. Recognizing a seizure attack is easy if the patient presents with generalized tonic-clonic seizure. But when the presentation is of atypical form, noticing it in the first instance might become difficult even in a tertiary medical center. Anti-GAD65 antibody-related neurologic disorders have been reported to have a broad clinical spectrum. It can present as an autoimmune encephalitis with seizure attack. The seizure types reported previously included simple partial seizure, complex partial seizure, or generalized tonic-clonic seizure, but in previous studies, descriptions about the detail of semiology were scarce. No previously cases have been reported that presented with gelastic seizure[8,9]. Besides, autoimmune encephalitis-related epilepsy has some features, including an unusually high seizure frequency, short duration of each seizure, and intra-individual seizure variability or multifocality[10,11], that were compatible with our patient’s clinical course.

The strong point of our case report was the detailed seizure semiology description with EEG correlation. The most unique character of our patient was the gelastic seizure. Gelastic seizure is a rare type of seizure where the patients act like they are smiling during the seizure attack. The etiologies are various, and the most famous one is hypothalamic hamartoma in children, which was confirmed to have intrinsic epileptogenicity. The typical presentation of gelastic seizure includes laughter-like sound often combined with facial contraction to form a smiling appearance. Consciousness status may be impaired. It might also have some concurrent autonomic features[12]. One study reported 30 patients with the diagnosis of gelastic seizure but without hypothalamic hamartoma; most of their EEG monitoring showed focal or multifocal abnormalities involving mainly the frontal and/or temporal regions. Besides, 19 of them had unremarkable neuroimaging findings[13]. In our case, many examinations were performed to evaluate the possible etiologies of her gelastic seizure including the survey for autoimmune disorders and malignancy. The only positive finding was anti-GAD65 antibody, which confirmed the diagnosis of autoimmune encephalitis. The seizure attack ceased soon after steroid was prescribed, and did not recur thereafter. Hence, we believe GAD65-positive autoimmune encephalitis resulted in our case’s epilepsy.

In treating autoimmune encephalitis-related epilepsy, Feyissa and his colleagues[14] reported 252 patients diagnosed with autoimmune encephalitis with different autoantibodies. Of these patients, 20% initially presented with seizure; some of them were treated with immunotherapy in combination with anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs); but some of them were treated with AEDs alone. The majority of patients who responded to AEDs alone were voltage gated potassium channel-complex antibody positive, while those who had anti-GAD65 antibody were less likely to be controlled with AEDs alone[14].

As the treatment of autoimmune encephalitis caused by anti-GAD65 antibody, previous case reports showed inconsistent results of different kinds of management. Some patients responded to steroid, but some others responded to immunoglobulin[15]. The excellent treatment response of our patient to pulse therapy of steroid might give us more confidence to encourage the use of steroid as the first-line treatment in anti-GAD65 antibody-related autoimmune encephalitis, which is easier to get and more affordable than immunoglobulin therapy in most countries.

GAD65 autoantibody is well known for its relationship with autoimmune diabetes, mostly type I diabetes and even in a subset of type II diabetes[16]. In our patient, the most recent measured HbA1c was 4.9% (normal upper limit 6% in our hospital); she was receiving peritoneal dialysis for a long time, possibly due to malignant hyper

The underlying mechanisms of why anti-GAD antibody causes neurologic mani

As the patient has chronic kidney disease and was receiving peritoneal dialysis, it raises a question of whether the presence of anti-GAD65 antibody is related to chronic kidney disease. Some reports demonstrate the strong relationships between type 1 diabetes and end stage renal diseases[19,20], and anti-GAD65 antibody is frequently found in type 1 diabetes, but currently there are no studies directly discussing the connection between anti-GAD65 antibody and chronic kidney disease. We still lack evidence to declare that anti-GAD65 antibody could result from chronic kidney disease or not. We need further investigation to clarify this issue.

This report has a main limitation. The data of our patient’s anti-GAD65 antibody was qualitative rather than quantitative (Supplementary Figure 1), although a previous published study[1] believed that disease severity and GAD-antibody concentration had no correlation.

During evaluation of patients with new-onset epilepsy, considering the possibility of autoimmune encephalitis is important, particularly in patients who have no obvious etiology and are refractory to standard treatment. This rare case was presented in detail as a reminder that anti-GAD65 antibody autoimmune encephalitis is a possible cause of temporal lobe epilepsy, although it is more known to cause stiff person syndrome, and it could present as gelastic seizure. Also, pulse therapy with steroid should be considered as the first-line treatment of autoimmune encephalitis due to its easy accessibility.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Clinical Neurology

Country/Territory of origin: Taiwan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ferreira GSA, Teragawa H, Velikova T S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Yuan YY

| 1. | Jazebi N, Rodrigo S, Gogia B, Shawagfeh A. Anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) positive cerebellar Ataxia with transitioning to progressive encephalomyelitis with rigidity and myoclonus (PERM), responsive to immunotherapy: A case report and review of literature. J Neuroimmunol. 2019;332:135-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Liu Z, Huang Q, Li H, Qiu W, Chen B, Luo J, Yang H, Liu T, Liu S, Xu H, Long Y, Gao C. Glutamic Acid Decarboxylase Antibody in a Patient with Myelitis: A Retrospective Study. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2018;25:68-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Nemni R, Braghi S, Natali-Sora MG, Lampasona V, Bonifacio E, Comi G, Canal N. Autoantibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase in palatal myoclonus and epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 1994;36:665-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Joubert B, Rostásy K, Honnorat J. Immune-mediated ataxias. Handb Clin Neurol. 2018;155:313-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fileccia E, Rinaldi R, Liguori R, Incensi A, D'Angelo R, Giannoccaro MP, Donadio V. Post-ganglionic autonomic neuropathy associated with anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase antibodies. Clin Auton Res. 2017;27:51-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Manto M, Honnorat J, Hampe CS, Guerra-Narbona R, López-Ramos JC, Delgado-García JM, Saitow F, Suzuki H, Yanagawa Y, Mizusawa H, Mitoma H. Disease-specific monoclonal antibodies targeting glutamate decarboxylase impair GABAergic neurotransmission and affect motor learning and behavioral functions. Front Behav Neurosci. 2015;9:78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kuo YC, Lin CH. Clinical spectrum of glutamic acid decarboxylase antibodies in a Taiwanese population. Eur J Neurol. 2019;26:1384-1390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Daif A, Lukas RV, Issa NP, Javed A, VanHaerents S, Reder AT, Tao JX, Warnke P, Rose S, Towle VL, Wu S. Antiglutamic acid decarboxylase 65 (GAD65) antibody-associated epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;80:331-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chengyu L, Weixiong S, Chao C, Songyan L, Lin S, Zhong Z, Hua P, Fan J, Na C, Tao C, Jianwei W, Haitao R, Hongzhi G, Xiaoqiu S. Clinical features and immunotherapy outcomes of anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 antibody-associated neurological disorders. J Neuroimmunol. 2020;345:577289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lv RJ, Ren HT, Guan HZ, Cui T, Shao XQ. Seizure semiology: an important clinical clue to the diagnosis of autoimmune epilepsy. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2018;5:208-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Quek AM, Britton JW, McKeon A, So E, Lennon VA, Shin C, Klein C, Watson RE Jr, Kotsenas AL, Lagerlund TD, Cascino GD, Worrell GA, Wirrell EC, Nickels KC, Aksamit AJ, Noe KH, Pittock SJ. Autoimmune epilepsy: clinical characteristics and response to immunotherapy. Arch Neurol. 2012;69:582-593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 245] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Téllez-Zenteno JF, Serrano-Almeida C, Moien-Afshari F. Gelastic seizures associated with hypothalamic hamartomas. An update in the clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2008;4:1021-1031. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Iapadre G, Zagaroli L, Cimini N, Belcastro V, Concolino D, Coppola G, Del Giudice E, Farello G, Iezzi ML, Margari L, Matricardi S, Orsini A, Parisi P, Piccioli M, Di Donato G, Savasta S, Siliquini S, Spalice A, Striano S, Striano P, Verrotti A. Gelastic seizures not associated with hypothalamic hamartoma: A long-term follow-up study. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;103:106578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Feyissa AM, López Chiriboga AS, Britton JW. Antiepileptic drug therapy in patients with autoimmune epilepsy. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2017;4:e353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Li TR, Zhang YD, Wang Q, Shao XQ, Li ZM, Lv RJ. Intravenous methylprednisolone or immunoglobulin for anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 antibody autoimmune encephalitis: which is better? BMC Neurosci. 2020;21:13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Towns R, Pietropaolo M. GAD65 autoantibodies and its role as biomarker of Type 1 diabetes and Latent Autoimmune Diabetes in Adults (LADA). Drugs Future. 2011;36:847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Koerner C, Wieland B, Richter W, Meinck HM. Stiff-person syndromes: motor cortex hyperexcitability correlates with anti-GAD autoimmunity. Neurology. 2004;62:1357-1362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mitoma H, Adhikari K, Aeschlimann D, Chattopadhyay P, Hadjivassiliou M, Hampe CS, Honnorat J, Joubert B, Kakei S, Lee J, Manto M, Matsunaga A, Mizusawa H, Nanri K, Shanmugarajah P, Yoneda M, Yuki N. Consensus Paper: Neuroimmune Mechanisms of Cerebellar Ataxias. Cerebellum. 2016;15:213-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lin WH, Li CY, Wang WM, Yang DC, Kuo TH, Wang MC. Incidence of end stage renal disease among type 1 diabetes: a nationwide cohort study in Taiwan. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014;93:e274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Otani T, Yokoyama H, Hanai K, Miura J, Uchigata Y, Babazono T. Rapid increase in the incidence of end-stage renal disease in patients with type 1 diabetes having HbA1c 10% or higher for 15 years. Clin Pediatr Endocrinol. 2019;28:113-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |