Published online Jul 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i19.5294

Peer-review started: February 13, 2021

First decision: March 14, 2021

Revised: March 16, 2021

Accepted: April 23, 2021

Article in press: April 23, 2021

Published online: July 6, 2021

Processing time: 130 Days and 18.2 Hours

Congenital transmesenteric hernia in children is a rare and potentially fatal form of internal abdominal hernia, and no specific clinical symptoms can be observed preoperatively. Therefore, this condition is not widely known among clinicians, and it is easily misdiagnosed, resulting in disastrous effects.

This report presents the case of a 13-year-old boy with a chief complaint of abdominal pain and vomiting and a history of duodenal ulcer. The patient was misdiagnosed with gastrointestinal bleeding and treated conservatively at first. Then, the patient’s symptoms were aggravated and he presented in a shock-like state. Computed tomography revealed a suspected internal hernia, extensive small intestinal obstruction, and massive effusion in the abdominal and pelvic cavity. Intraoperative exploration found a small mesenteric defect approximately 3.5 cm in diameter near the ileocecal valve, and there was about 1.8 m of herniated small intestine that was treated by resection and anastomosis. The patient recovered well and was followed for more than 5 years without developing short bowel syndrome.

In this report, we review the pathogenesis, presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of congenital transmesenteric hernia in children.

Core Tip: Congenital transmesenteric hernia in children is a rare and challenging disease that usually lacks specific clinical symptoms, hindering a correct preoperative diagnosis. Here, we first report an interesting case of intestinal gangrene secondary to congenital transmesenteric hernia in a child misdiagnosed with gastrointestinal bleeding, with the purpose of generalizing and reviewing the pathogenesis, presen

- Citation: Zheng XX, Wang KP, Xiang CM, Jin C, Zhu PF, Jiang T, Li SH, Lin YZ. Intestinal gangrene secondary to congenital transmesenteric hernia in a child misdiagnosed with gastrointestinal bleeding: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(19): 5294-5301

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i19/5294.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i19.5294

Congenital transmesenteric hernia is a rare and potentially fatal form of internal abdominal hernia, and it is one of the leading causes of abdominal internal hernias in children[1-3]. The early symptoms of congenital transmesenteric hernia are atypical, and 30% of cases remain without symptoms for a lifetime[4]. The symptoms of congenital transmesenteric hernia are dependent on the diameter of the mesenteric defect. When the defect is too large or too small, the patient is usually asymptomatic. When the small intestine repeatedly passes through the mesenteric defect, the patient shows symptoms such as intermittent abdominal pain and abdominal distension. If the herniated intestine cannot relieve, it gradually develops into intestinal obstruction and leads to intestinal necrosis. If the herniated intestine relieves, it shows long-term intermittent abdominal pain with unknown causes or recurrent intestinal obstruction. Therefore, the relatively typical symptoms of congenital transmesenteric hernia range from chronic mild abdominal discomfort to nausea, vomiting, and abdominal disten

Congenital mesenteric defects or abnormal embryologic development may be the cause of congenital transmesenteric hernia[5], but the exact pathogenesis is still unclear. Due to the lack of a hernial sac, the preoperative diagnosis of congenital transmesenteric hernia is much more challenging than that of other acute abdominal presentations[3]. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) seems to be the recommen

Motivated by the challenge of diagnosing congenital transmesenteric hernia, here, we first report an interesting case of intestinal gangrene secondary to congenital transmesenteric hernia in a child misdiagnosed with gastrointestinal bleeding, with the purpose of generalizing and reviewing the pathogenesis, presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of congenital transmesenteric hernia in children.

A 13-year-old boy complained of abdominal pain for 1 d and vomiting with fatigue for 12 h.

The child developed severe paroxysmal pain around the navel 1 d prior, but there was no haematemesis or haematochezia. After admission, the patient’s abdominal pain and abdominal distension were obviously aggravated, and he vomited once, producing coffee-like substance, and the vomiting was non-bilious and non-projectile. He also produced black stool once, and felt weak. Re-examination of CT revealed a suspected internal hernia, extensive small intestinal obstruction, and massive effusion in the abdominal and pelvic cavity.

The patient had a history of "Henoch-Schonlein purpura and duodenal ulcer" for 1 year.

The patient’s temperature was 36.6 °C, his heart rate fluctuated between 142 beats/min and 156 beats/ min, his respiratory rate was 39 breaths/min, his ambulatory blood pressure was between 86-96 pm and 52-63 mmHg, and his blood oxygen saturation was maintained above 92%. His complexion was pale, his conjunctiva was pale, his abdominal muscles were slightly tense, the whole abdomen was tender, there was no rebound pain, and the bowel sounds were weak. There was no rash anywhere on his body.

The blood routine tests on the day before admission were as follows: White blood cell count 13.1 × 109/L, neutrophils 33%, and hemoglobin 152 g/L. His platelets and coagulation function were normal.

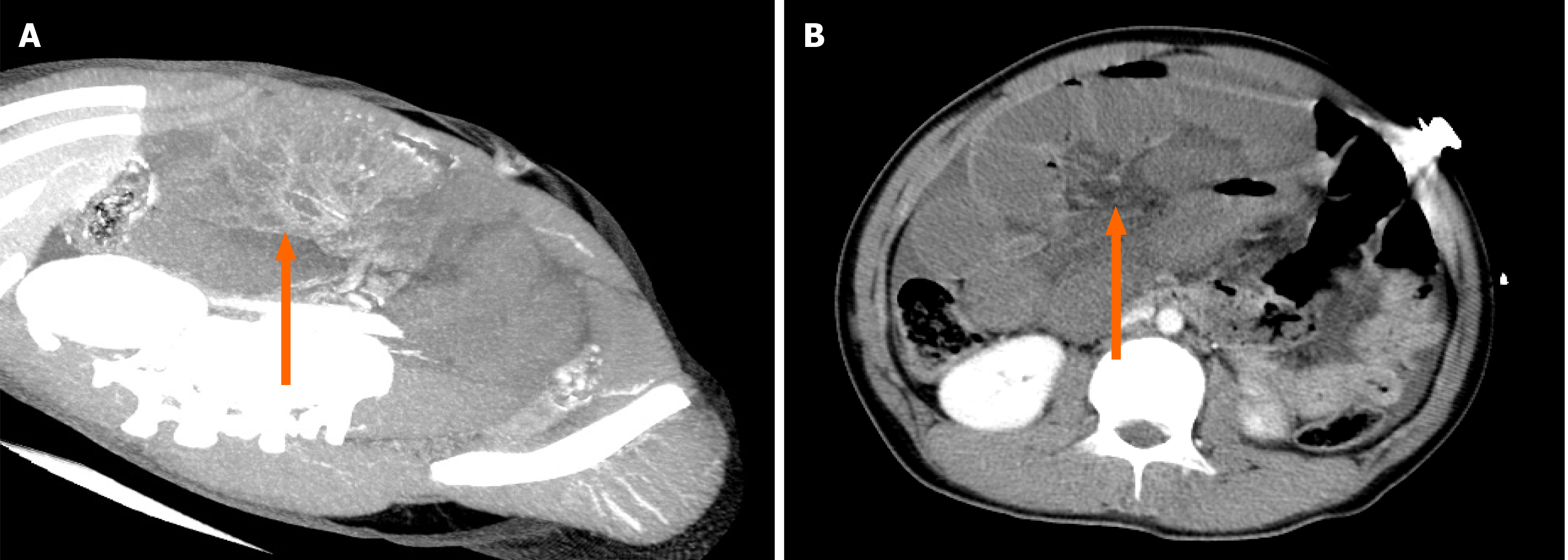

A CT scan of the entire abdomen before admission revealed no abnormality. After admission, re-examination of the CT revealed a suspected internal hernia, extensive small intestinal obstruction, and massive effusion in the abdominal and pelvic cavity (Figure 1). Abdominal puncture was performed to draw out the noncoagulable blood.

The final diagnosis was as follows: (1) Intra-abdominal bleeding, (2) Haemorrhagic shock, (3) Congenital transmesenteric hernia, and (4) Intestinal necrosis.

The patient was admitted to the Pediatric Internal Medicine Department at first, and there was no obvious abnormality on the first CT examination, but the patient’s hemoglobin showed a downward trend. Combined with the patient's previous history of a duodenal ulcer, the primary diagnosis was gastrointestinal bleeding caused by a duodenal ulcer, so he was given conservative treatment, such as fasting, protecting stomach, rehydration, and gastrointestinal decompression. However, the patient's symptoms were obviously aggravated, the patients developed marked abdominal distension and marked pallor. Re-physical examination revealed the following: Heart rate 150 bpm, blood pressure of 88/32 mmHg, abdominal tension, total abdominal tenderness, and reduced bowel sounds. There was no bloody fluid in the nasogastric tube. Therefore, we no longer considered the suspicious diagnosis of gastrointestinal bleeding, but considered intra-abdominal bleeding, so we did not take esophagogastroduodenoscopy, but CT re-examination (5 h after the first) while preparing for emergency laparotomy. Re-examination of abdominal CT suggested a suspected internal hernia, extensive small intestinal obstruction, and massive effusion in the abdominal and pelvic cavity (Figure 1). Then, abdominal puncture was performed to draw out noncoagulable blood.

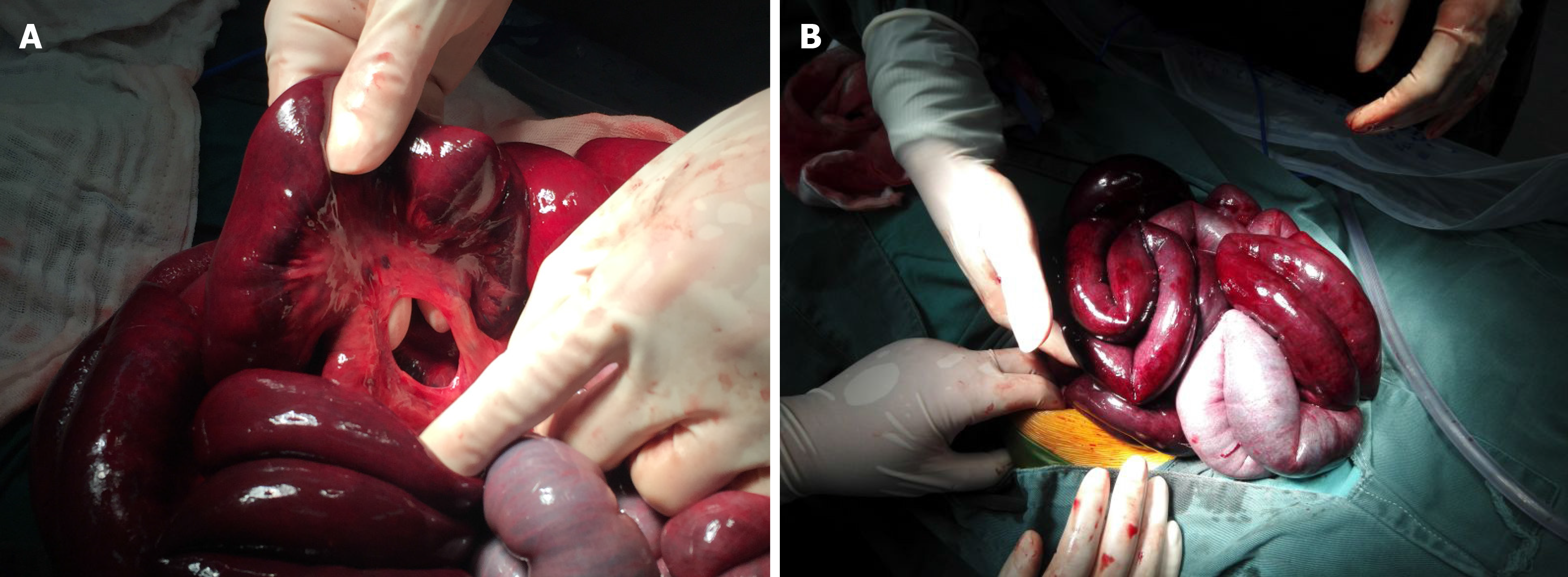

Next, emergency laparotomy was performed at the same time as antishock treatment. Intraoperative exploration found that there was approximately 1000 mL of bloody fluid in the abdominal cavity, a small mesenteric defect approximately 3.5 cm in diameter near the ileocecal valve (Figure 2A), and 1.8 m of herniated small intestine (Figure 2B). The distal end of the necrotic small intestine was approximately 1.8 m from the suspensory ligament of the duodenum and approximately 50 cm from the ileocecal part. During the operation, after freeing the intestine, it was observed for 30 min before deciding that the section of the intestine was completely necrotic, so the patient was treated by resection and anastomosis.

The patient was discharged safely 1 wk after the operation and followed for more than 5 years without developing short bowel syndrome.

The first case of congenital transmesenteric hernia was found at autopsy by Rokitansky in 1836[7]. Previously, it was generally believed that Treves' field located near the end of the ileum was the most common site of congenital transmesenteric hernia because of its lack of fat and visible blood vessels[4]. However, there are some reports showing congenital transmesenteric hernias that do not occur in Treves' field[2,3,8-10]. There is no consensus on the pathogenesis of congenital transmesenteric hernia, although there are several common theories, including degeneration of the dorsal mesentery, abnormal development of a hypovascular area, rapid extension of the mesentery, and compression of the mesentery by abnormal embryonic develo

In general, no specific clinical symptom of congenital transmesenteric hernia can be observed preoperatively, and the symptoms range from mild gastrointestinal discomfort to an acute abdomen, which depends on the severity of the incarceration and obstruction of the intestine[11]. The early symptoms of most patients are not obvious, but the disease usually progresses rapidly. Once incarcerated, it easily progresses to intestinal gangrene, which is a serious threat to the patient's life. The time from symptom onset to admission and then to an accurate diagnosis usually takes longer than 1 d[4]. In this case, the patient had symptoms such as abdominal pain, vomiting (he vomited once, producing coffee-like substance, and the vomiting was non-bilious and non-projectile) and bloody stool before the operation and had a previous history of duodenal ulcer; hence, he was easily misdiagnosed with gastro

The diagnosis of congenital transmesenteric hernia is difficult, and the risk of obstruction and incarceration is much more critical than that of other internal abdominal hernias, such as paraduodenal hernias[12]. There are no objective laboratory examinations to confirm the diagnosis. Laboratory tests might show leukocytosis and metabolic acidosis at an early time but are usually within normal limits[7]. The location of abdominal pain is not specific for a diagnosis. When there is a decline in hemoglobin, this often indicates that the disease has progressed to a more dangerous stage, and it is necessary to make an accurate diagnosis and take treatment measures as soon as possible.

However, an accurate diagnosis of congenital transmesenteric hernia is usually only confirmed after abdominal exploration. To clarify the diagnosis of congenital transmesenteric hernia, many researchers have analyzed the risk factors for congenital transmesenteric hernia, such as old age (> 70 years), high white blood cell count (> 18000/mm3), shock, hypothermia, rectal bleeding, and abdominal rigidity[11]. Moreover, Fan et al reviewed the medical records, imaging studies, and operative findings of 20 patients in their medical centre and found that patients have a very high risk of intestinal ischaemia if they present with abdominal rebound tenderness or advanced leukocytosis[11]. These findings provide a meaningful reference basis for clinical diagnosis.

CT is the most recommended imaging examination with a sensitivity of 63%, specificity of 76%, and accuracy of 77%, and it is usually necessary to recheck the CT to make a definite diagnosis[6]. In some special cases, abdominal puncture can also be used to assist in the diagnosis. In our case, the diagnosis was not confirmed until the second CT examination.

Surgery is the only treatment for intestinal necrosis caused by congenital transmesenteric hernia. The choice of operation method depends on the intraoperative exploration and the patient’s condition. There are two main surgical options: Resection and anastomosis and resection and descending colostomy. Malnutrition caused by short bowel syndrome is the most serious postoperative complication. If the residual small intestine with an intact colon is less than 75 cm, or after ileocecal valve resection, the residual small intestine is less than 100 cm, this can lead to short bowel syndrome [13].

Most mesenteric defects that lead to congenital transmesenteric hernia occur in the small intestine mesentery and are round to oval shaped with a diameter of 2-3 cm[2]. In this case, we found a small mesenteric hiatal hernia approximately 3.5 cm in diameter 50 cm from the ileocecum. A congenital transmesenteric hernia with a mesenteric defect diameter > 30 cm has also been reported[7]. Although the mouth of mesenteric defects with a relatively small diameter does not easily cause incarcerated hernias, once incarceration occurs, the condition is more dangerous. We emphasize the importance of CT in the correct preoperative diagnosis of congenital transmesenteric hernia. However, only if time permits, CT examination should be carried out, which does not mean that all patients must have CT examination. If the patient's condition progresses rapidly, emergency laparotomy can be performed directly to avoid delay in rescue due to CT examination.

Compared with infants and adults, congenital transmesenteric hernia in children has its own particularity. This is mainly reflected in the fact that the incidence of congenital mesenteric hiatus hernia in children is lower, there is no history of operations, and the clinical symptoms lack specificity. Therefore, it is extremely easy to misdiagnosis it. We summarize some characteristics of 14 cases of congenital transmesenteric hernia in children (1-18 years old) reported in the literature since 2002 (Table 1).

| No. | Ref. | Age/gender | Symptoms and signs | Time from symptom onset to surgery | Location of mesenteric defect | Diameter of mesenteric defect (cm) | Treatment | Length of resected bowel (cm) | Postoperative complications | Outcome |

| 1 | Garignon et al[8], 2002 | 3/M | Abdominal pain, bilious vomiting, non-projectile | 2 d | Near the jejuno-ileal junction | Very large | Resection and anastomosis | / | None | Recovered well |

| 2 | Ming et al[9], 2007 | 2.5/M | Abdominal pain, abdominal distention, shock-like state, bilious vomiting, non-projectile | / | 40 cm proximal to ileocecal valve | 2 | Resection and anastomosis | / | None | Recovered well |

| 3 | Ming et al[9], 2007 | 3.2/M | Abdominal pain, abdominal distention, bilious vomiting, non-projectile | / | 35 cm proximal to ileocecal valve | 3 | Resection and anastomosis | / | None | Recovered well |

| 4 | Ming et al[9], 2007 | 2.2/M | Abdominal pain, palpable mass, shock-like state, bilious vomiting, non-projectile | / | 20 cm proximal to ileocecal valve | 7 | Resection and ileostomy | / | Wound infection | / |

| 5 | Ming et al[9], 2007 | 5.4/F | Abdominal pain, abdominal distention, bilious vomiting, non-projectile | / | 100 cm proximal to ileocecal valve | 4 | Resection and anastomosis | / | None | Recovered well |

| 6 | Page et al[7], 2008 | 1.8/F | Abdominal pain, nonbilious vomiting, non-projectile | More than 2 d | Terminal ileum | 30 | Resection and descending colostomy | / | None | Recovered well |

| 7 | Park et al[14], 2009 | 7/F | Diffuse abdominal pain, chocolate-colored vomiting, non-projectile | More than 20 h | Near the ileum | 15 | Resection and anastomosis | 180 | None | Recovered well |

| 8 | Lee et al[12], 2013 | 6/M | Abdominal pain, vomiting of clear fluid twice, non-projectile | More than 15 h | Near the ileocecal valve | 2 finger breadth | Resection and anastomosis | More than 200 | None | Recovered well |

| 9 | Saka et al[4], 2015 | 5/F | Abdominal pain, non-bilious vomiting, non-projectile | 2 d | Near the ileocecal valve | 5 | Resection and anastomosis | 106 | Loose stool | Recovered well |

| 10 | Saka et al[4], 2015 | 11/F | Abdominal pain, non-bilious vomiting, non-projectile | 2 d | Near the ileocecal valve | 3 | Resection and anastomosis | 100 | Loose stool | Recovered well |

| 11 | Saka et al[4], 2015 | 8/F | Abdominal pain, non-bilious vomiting, non-projectile | 1 d | Near the ileocecal valve | 10 | Resection and anastomosis | 150 | Loose stool | Recovered well |

| 12 | Saka et al[4], 2015 | 5/F | Abdominal pain, non-bilious vomiting, non-projectile | 1 d | Near the ileocecal valve | 10 | Resection and anastomosis | 60 | None | Recovered well |

| 13 | Willems et al[2], 2018 | 11/F | Abdominal pain, non-bilious vomiting, non-projectile | 1 d | Near the ileocecal valve | 2 | Resection and anastomosis | / | None | Recovered well |

| 14 | Our case | 13/M | Abdominal pain, coffee-like vomiting, non-projectile | 1 d | Near the ileocecal valve | 3.5 | Resection and anastomosis | 180 | None | Recovered well |

After reviewing the 13 cases reported in the English literature and synthesizing them with our case, the incidence of congenital transmesenteric hernia was found to be similar in boys and girls (6:8, P > 0.05), with a median age of symptom onset of 5.2 years old (range: 1.8-13 years old). All cases had the same symptoms of abdominal pain and vomiting (14/14). All patients had non-projectile vomiting, five had bilious vomiting, and nine had non-bilious vomiting (one was chocolate-like, one was water-like, and our case was coffee-like). The symptoms of vomiting did not indicate congenital transmesenteric hernia, although the coffee-like symptom was relatively rare in our case. There is no significant difference in the clinical manifestations of congenital transmesenteric hernia between adults and children. Only two patients had a shock-like state. The median time from symptom onset to surgery was 1 d (range: 0.625-2 d). The most common location of the mesenteric defect that led to a congenital transmesenteric hernia was in Treves’ field (9/14). The median diameter of the mesenteric defects was 4.5 cm (range: 2-30 cm). All of the patients underwent surgical treatment; one patient underwent resection and descending colostomy, one underwent resection and ileostomy, and the rest were treated by resection and anastomosis. The median length of the resected bowel was 150 cm (range: 60-200 cm). Regarding postoperative complications, only three patients had complications of loose stool, and one had a wound infection. All of the patients recovered well and one patient was lost to follow-up.

In conclusion, congenital transmesenteric hernia in children is a rare and challenging disease that usually lacks specific clinical symptoms to guide a correct preoperative diagnosis, and it should be differentiated from gastrointestinal bleeding. Examination by CT is helpful in improving the accurate preoperative diagnosis of congenital transmesenteric hernia. Surgery is a safe and effective choice for the treatment of congenital transmesenteric hernia.

We are very grateful to our colleagues from the Department of Imaging for providing the computed tomography pictures.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Sintusek P, Teragawa H S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Ai W, Liang Z, Li F, Yu H. Internal hernia beneath superior vesical artery after pelvic lymphadenectomy for cervical cancer: a case report and literature review. BMC Surg. 2020;20:312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Willems E, Willaert B, Van Slycke S. Transmesenteric hernia: a rare case of acute abdominal pain in children: a case report and review of the literature. Acta Chir Belg. 2018;118:388-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tang V, Daneman A, Navarro OM, Miller SF, Gerstle JT. Internal hernias in children: spectrum of clinical and imaging findings. Pediatr Radiol. 2011;41:1559-1568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Saka R, Sasaki T, Nara K, Hasegawa T, Nose S, Okuyama H, Oue T. Congenital Treves' field transmesenteric hernia in children: A case series and literature review. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep. 3:351-355. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mathieu D, Luciani A; GERMAD Group. Internal abdominal herniations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:397-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Blachar A, Federle MP, Dodson SF. Internal hernia: clinical and imaging findings in 17 patients with emphasis on CT criteria. Radiology. 2001;218:68-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 245] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Page MP, Ricca RL, Resnick AS, Puder M, Fishman SJ. Newborn and toddler intestinal obstruction owing to congenital mesenteric defects. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:755-758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Garignon C, Paparel P, Liloku R, Lansiaux S, Basset T. Mesenteric hernia: a rare cause of intestinal obstruction in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:1493-1494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ming YC, Chao HC, Luo CC. Congenital mesenteric hernia causing intestinal obstruction in children. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166:1045-1047. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Shiozaki H, Sakurai S, Sudo K, Shimada G, Inoue H, Ohigashi S, Deshpande GA, Takahashi O, Onodera H. Pre-operative diagnosis and successful surgery of a strangulated internal hernia through a defect in the falciform ligament: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Fan HP, Yang AD, Chang YJ, Juan CW, Wu HP. Clinical spectrum of internal hernia: a surgical emergency. Surg Today. 2008;38:899-904. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lee N, Kim SG, Lee YJ, Park JH, Son SK, Kim SH, Hwang JY. Congenital internal hernia presented with life threatening extensive small bowel strangulation. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2013;16:190-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Geng L, Zhou L, Ding GJ, Xu XL, Wu YM, Liu JJ, Fu TL. Alternative technique to save ischemic bowel segment in management of neonatal short bowel syndrome: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7:3353-3357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Park CY, Kim JC, Choi SJ, Kim SK. A transmesenteric hernia in a child: gangrene of a long segment of small bowel through a large mesenteric defect. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2009;53:320-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |