Published online Jul 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i19.5266

Peer-review started: February 3, 2021

First decision: February 28, 2021

Revised: March 3, 2021

Accepted: May 15, 2021

Article in press: May 15, 2021

Published online: July 6, 2021

Processing time: 140 Days and 15.5 Hours

Since the initial recognition of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, this infectious disease has spread to most areas of the world. The pathogenesis of COVID-19 is yet unclear. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation occurring in COVID-19 patients has not yet been reported.

A 45-year-old hepatitis B man with long-term use of adefovir dipivoxil and entecavir for antiviral therapy had HBV reactivation after being treated with methylprednisolone for COVID-19 for 6 d.

COVID-19 or treatment associated immunosuppression may trigger HBV reactivation.

Core Tip: In this study, the authors found that coronavirus disease 2019 or treatment associated immunosuppression may trigger hepatitis B virus reactivation.

- Citation: Wu YF, Yu WJ, Jiang YH, Chen Y, Zhang B, Zhen RB, Zhang JT, Wang YP, Li Q, Xu F, Shi YJ, Li XP. COVID-19 or treatment associated immunosuppression may trigger hepatitis B virus reactivation: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(19): 5266-5269

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i19/5266.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i19.5266

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation occurs primarily when body immunity declines due to the use of chemotherapy, long-term glucocorticoids, or immunosuppressive therapy[1]. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an emerging global viral infectious disease. The pathogenesis of COVID-19 is still unclear[2]. Whether HBV reactivation occurs in COVID-19 patients has not yet been reported.

A 45-year-old man was admitted to the hospital for fever and fatigue after his way back from Wuhan, China 2 d ago.

The patient had a history of HBV infection for over 20 years. He was initially treated with adefovir dipivoxil and entecavir since then. Adfovir was discontinued 5 years ago.

The patient had no history of high blood pressure, diabetes, heart disease, or tumor.

The patient was married at the age of 25, with two sons. His wife was in good health and his family relations were harmonious. His parents were alive and healthy, and his two younger sisters were healthy.

Physical examination revealed no swelling of lymph nodes throughout the body, clear breath sounds in both lungs, and no rales.

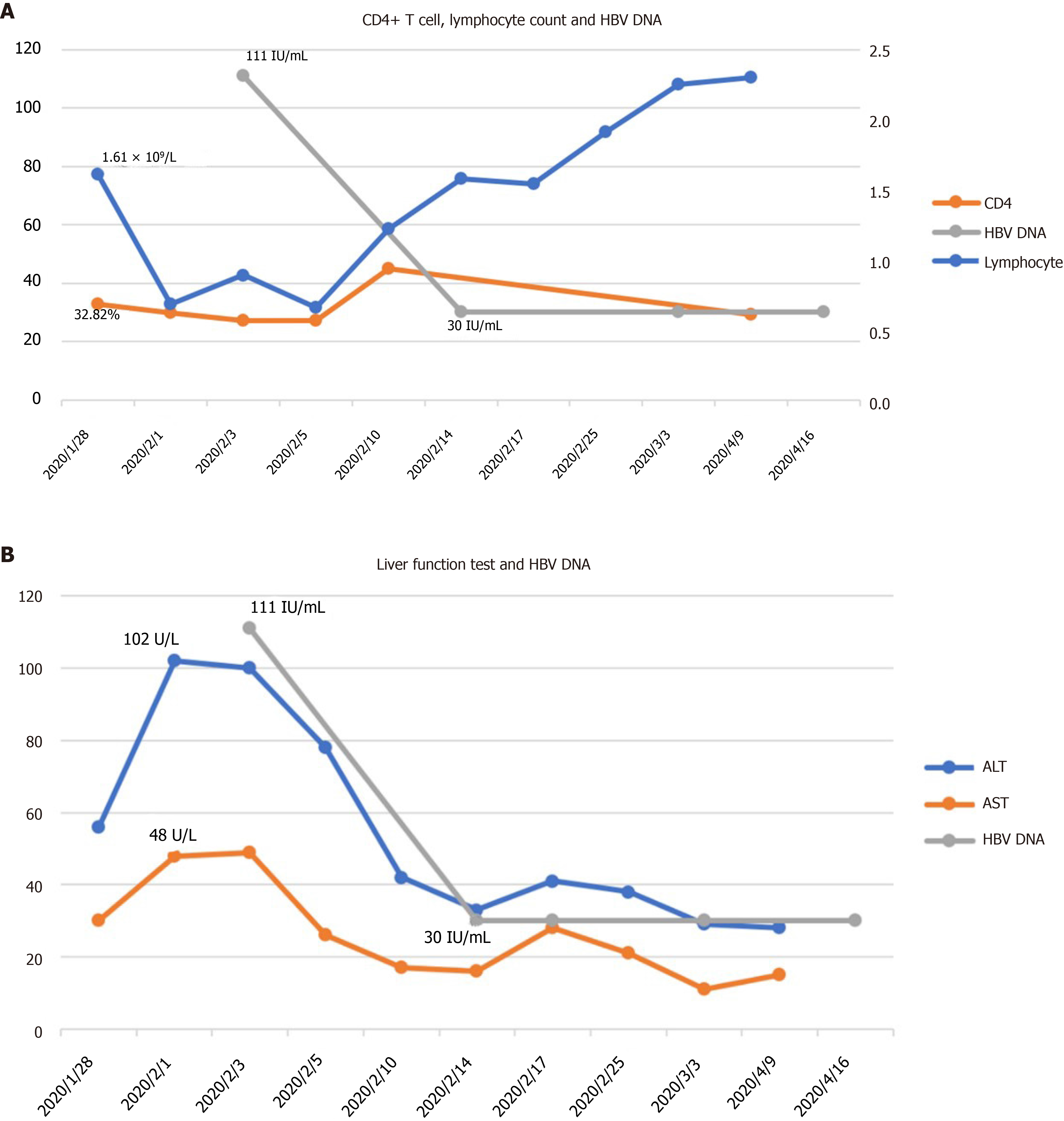

The patient was positive for nucleic acid test for COVID-19. The initial laboratory results included: His blood lymphocyte count was 1.61 × 109/L, the percentage of CD4+ T cells was 32.82%, and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) were 56 U/L and 30 U/L, respectively. After that, ALT was increased to 102 U/L, and AST was slightly increased to 48 U/L. HBV DNA was lower than the detection limit (30 IU/mL). Hepatitis B surface antigen was 1356 cutoff index (COI; < 1.000), hepatitis B surface antibody 2 iu/L (2-10 iu/L), hepatitis B e-antigen 0.34 COI (< 1.000), hepatitis B e-antibody 0.563COI (> 1.000), and hepatitis B c-antibody 0.416 COI (> 1.000).

On day 6, a chest computed tomography scan showed progressive pneumonia.

COVID-19 and hepatitis B virus infection.

After admission, the patient was treated with recombinant interferon-alpha-2b and lopinavir/ritonavir. Following this, he was treated with methylprednisolone (40 mg once daily). His lymphocyte count continued its downtrend to 0.89 × 109/L, CD4+ T cells further declined to 27.14%, and liver enzymes ALT and AST showed no significant changes. HBV DNA was increased to 1.11 × 102 IU/mL, although it was actually negative before this admission (Figure 1). Hence, tenofovir fumarate was added for possible HBV reactivation.

The patient started to be afebrile, and liver enzymes ALT and AST decreased to 42 U/L and 17 U/L, respectively. The nucleic acid test for COVID-19 became negative twice then. HBV DNA became lower than the detection limit (30 IU/mL). HBV drug resistance gene of the HBV P region was negative too. Then, the patient was discharged. Both liver enzymes and HBV DNA were within normal range after discharge from hospital.

As we know, unstandardized administration of nucleos(t)ide analog, glucocorticoids, chemotherapy drugs, and new biological agents such as monoclonal antibodies and antiviral drugs of hepatitis B virus can cause HBV reactivation[1]. This patient had used adefovir dipivoxil and entecavir for antiviral therapy for a long time. His HBV DNA was negative before the development of COVID-19. He had elevated liver enzymes and increased HBV DNA during the treatment of COVID-19. Thus, according to American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases guideline about the definition of HBV reactivation, he met the criteria for HBV reactivation. Besides, the long term usage of antiviral drugs that may cause HBV resistance to NAs is also possible[3]. However, his HBV resistance gene was tested and negative for entecavir and adefovir dipivoxil. Noncompliance is another reason that causes HBV reactivation[3], but our patient was followed in the clinic regularly, and he did not discontinue or reduce dose without physician’s advice. Therefore, it could be possible that HBV reactivation in this patient was caused by COVID-19 or related treatment. The mechanism of HBV reactivation is not yet fully understood. Once the immune homeostasis between the virus and the body is disturbed, HBV reactivation may occur[4]. Previous studies have shown that COVID-19 patients may have impaired immune function and lower lymphocyte count, especially CD4+ T lymphocytes[2]. And glucocorticoid usage may decrease cellular immune function sharply. As a novel infectious disease, the pathogenesis of COVID-19 is yet unclear. This is the first case report of COVID-19 complicated with HBV reactivation.

For COVID-19 patients complicated with hepatitis B, HBV reactivation may happen, and glucocorticoids need to be used cautiously.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Infectious Diseases

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D, D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Hammad M, Lashen SA, Pavides M S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Perrillo RP, Gish R, Falck-Ytter YT. American Gastroenterological Association Institute technical review on prevention and treatment of hepatitis B virus reactivation during immunosuppressive drug therapy. Gastroenterology 2015; 148: 221-244. e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 352] [Cited by in RCA: 390] [Article Influence: 39.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Winker B. [Remarks on the so-called feeling of hysteria]. Nervenarzt. 1988;59:752-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2495] [Cited by in RCA: 3331] [Article Influence: 666.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ganem D, Prince AM. Hepatitis B virus infection--natural history and clinical consequences. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1118-1129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1700] [Cited by in RCA: 1712] [Article Influence: 81.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Loomba R, Liang TJ. Hepatitis B Reactivation Associated With Immune Suppressive and Biological Modifier Therapies: Current Concepts, Management Strategies, and Future Directions. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1297-1309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 426] [Cited by in RCA: 439] [Article Influence: 54.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |