Published online Jul 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i19.5252

Peer-review started: January 30, 2021

First decision: February 25, 2021

Revised: February 28, 2021

Accepted: May 19, 2021

Article in press: May 19, 2021

Published online: July 6, 2021

Processing time: 144 Days and 23 Hours

Indwelling colon is characterized by an excluded segment of the colon after surgical diversion of the fecal stream with colostomy so that contents are unable to pass through this part of the colon. We report a rare case of purulent colonic necrosis that occurred 7 years after surgical colonic exclusion.

A 73-year-old male had undergone extended radical resection for rectosigmoid cancer. The invaded ileocecal area and sigmoid colon were removed during the procedure, and the ileum was anastomosed side-to-side with the rectum. The excluded ascending, transverse, and descending colon were sealed at both ends and left in the abdomen. After 7 years, the patient developed persistent abdominal pain and distension. Work-up indicated intestinal obstruction. The patient underwent ultrasound-guided catheter drainage of the descending colon and a large amount of viscous liquid was drained, but the symptoms persisted; therefore, surgery was planned. Intraoperatively, extensive adhesions were found in the abdominal cavity, and the small intestine and the indwelling colon were widely dilated. The dilated colon was 56 cm long, 5 cm wide (diameter), and contained about 1500 mL of viscous liquid. The indwelling colon was surgically removed and its histopathological examination revealed colonic congestion and necrosis with hyperplasia of granulation tissue. The bacterial culture of the secretions was negative. The patient recovered after the operation.

Although colonic exclusion is routinely performed, this report aimed to increase awareness regarding the possible long-term complications of indwelling colon.

Core Tip: We present a case of purulent colonic necrosis in an indwelling colon that occurred 7 years after colonic exclusion. Although colonic exclusion is routinely performed for a variety of colonic diseases, indwelling colon can present with long-term complications after several years. The mechanism due to which such complications develop remains unclear, but both disuse atrophy and diversion colitis seem to play a role in their pathology. Surgeons should avoid sealing both ends of the excluded colon. We recommend continuous surveillance for an earlier detection and treatment of such complications.

- Citation: Zhuang ZX, Wei MT, Yang XY, Zhang Y, Zhuang W, Wang ZQ. Long-term outcome of indwelling colon observed seven years after radical resection for rectosigmoid cancer: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(19): 5252-5258

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i19/5252.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i19.5252

Indwelling colon is characterized by an excluded segment of the colon after surgical diversion of the fecal stream with colostomy or ileostomy[1]. Evidence suggests that once there are no contents in the colon, prolonged colonic mucosal starvation may lead to functional and structural changes such as mucosal atrophy or mucosal inflammation, and these changes often aggravate with the passage of time[2]. So far, very few studies have investigated the long-term changes in the indwelling colon. Herein, we report a rare case of colonic purulent necrosis with poor prognosis, wherein the necrosis occurred 7 years after surgical colonic exclusion.

A 73-year-old man was admitted to West China Hospital of Sichuan University due to persistent abdominal pain and bloating for half a month.

The patient presented with persistent abdominal pain and distension approximately half a month before admission. Work-up indicated an intestinal obstruction. The patient underwent ultrasound-guided catheter drainage of a large amount of viscous liquid from the descending colon. The symptoms persisted and he was admitted to our hospital for surgery.

The patient was diagnosed with sigmoid colon neoplasms in June 2013. Emergency surgery was received by the patient. The invaded ileocecal area and sigmoid colon were removed during the procedure, and the ileum was anastomosed side-to-side with the rectum, achieving an R0 resection. The excluded ascending, transverse, and descending colon segments were sealed at both ends and left in the abdomen. Unfortunately, the patient was diagnosed with lung cancer 4 years later and underwent right lung cancer resection without neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in 2017.

The patient experienced no chronic or intermittent abdominal pain or other related symptoms during the follow-up period. He had no previous heart-related medical history, and no other significant medical or family history.

Physical examination revealed a bulging abdomen, tenderness near the original surgical incision, no obvious rebound pain and muscle tension.

The results of laboratory examinations are shown in Table 1.

| Result | Reference range | |

| WBC (× 109 L) | 14.58 | 3.5-9.5 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 13.5 | 13.0-17.5 |

| Plt (× 1000/UL) | 155 | 100-300 |

| PCT (ng/mL) | 1.39 | |

| CRP (mg/L) | 80.70 | |

| ALB (g/L) | 16.0 | |

| Na (mmol/L) | 132.3 | |

| K (mmol/L) | 3.94 | |

| GOT (IU/L) | 25 | |

| GPT (IU/L) | 27 | |

| INR | 1.33 | |

| PTT (s) | 39.0 | |

| CEA (ng/mL) | 2.19 | |

| CA199 (U/mL) | 1.91 |

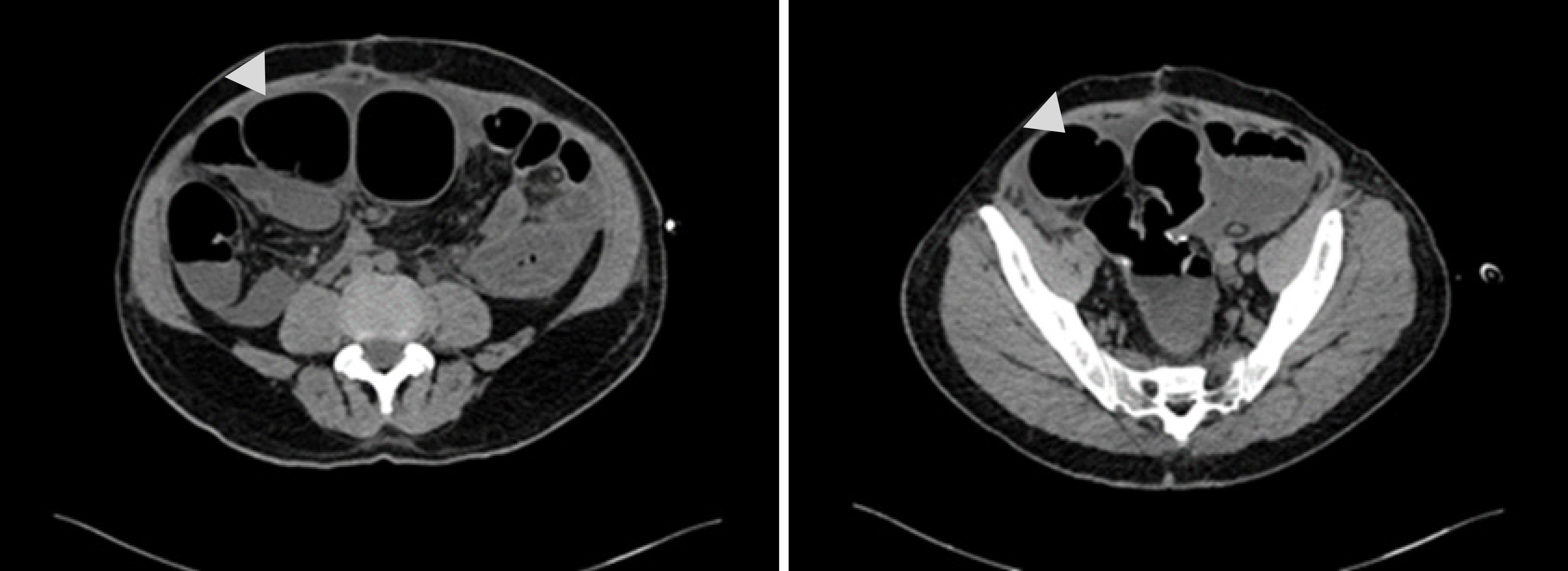

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan revealed severe intestinal distension with local short liquid gas level, multiple gas accumulation in the abdominal cavity and pelvis, part of the gastrointestinal wall swelling, signs of peritonitis, and incomplete intestinal obstruction (Figure 1). No clear signs of tumor metastasis and recurrence.

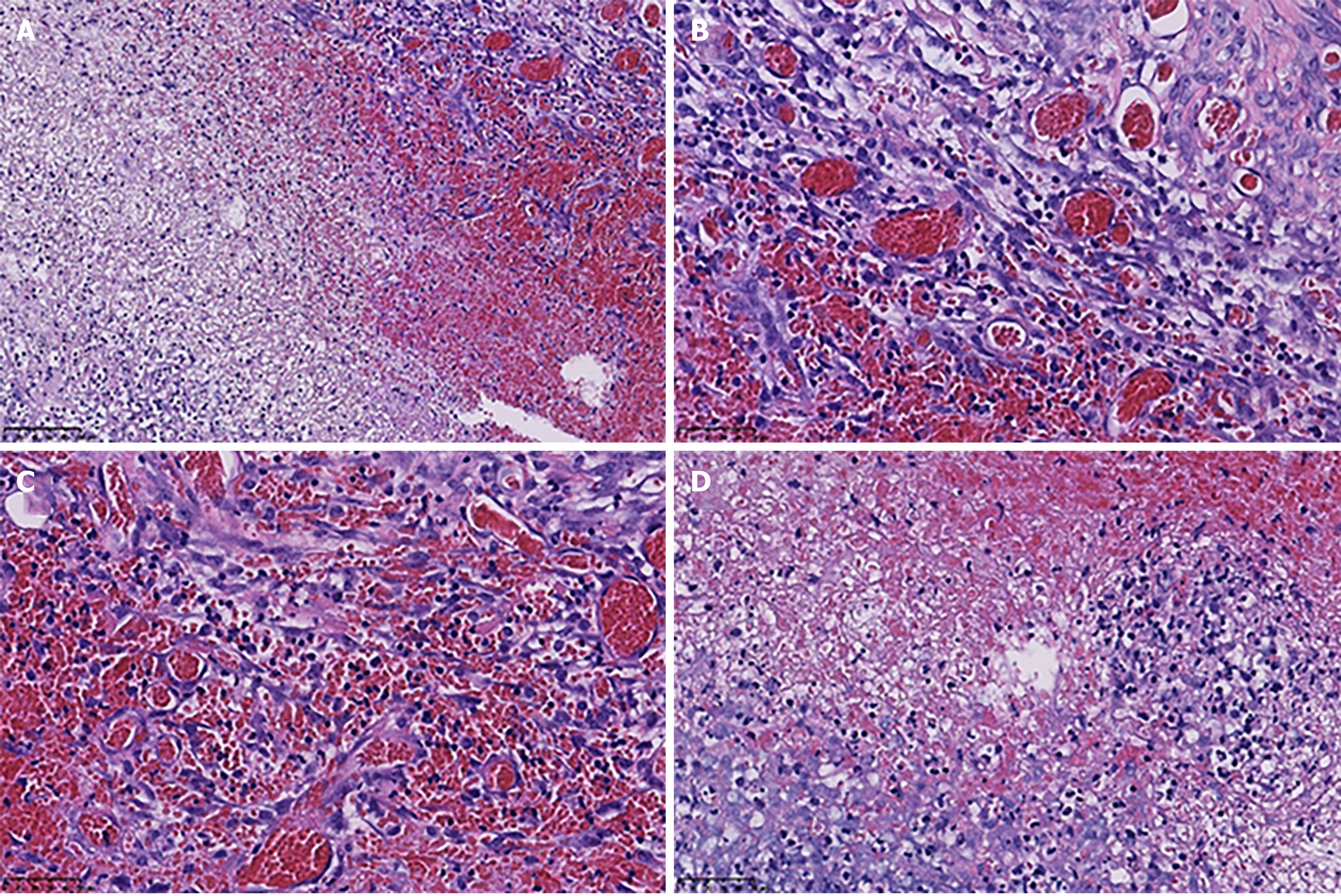

The indwelling colon histopathological examination revealed colonic congestion and necrosis with hyperplasia of granulation tissue.

After failure of conservative treatment, the patient underwent exploratory laparotomy. Intraoperatively, extensive adhesions were found in the abdominal cavity, and the small intestine and the indwelling colon were widely dilated (Figure 2). The dilated colon was 56 cm long, 5 cm wide (diameter), and contained about 1500 mL of viscous liquid (Figure 3). The indwelling colon was surgically removed.

A postoperative CT examination showed symptom relief. The indwelling colon histopathological examination revealed colonic congestion and necrosis with hyperplasia of granulation tissue. The bacterial culture of the secretions was negative (Figure 4). The patient recovered well after the operation.

Indwelling colon is characterized by an excluded segment of the colon after colostomy or ileostomy[1]. The intestinal contents are sufficiently diverted such that feces cannot reenter the distal colon temporarily, thereby minimizing the chances of infection. This is often employed as a surgical solution for a variety of colonic diseases[2].

The overall function of the colon is motility, secretion, nutrient absorption, and waste removal, and it handles approximately 9 L of fluid per day[3]. After diversion of the colonic contents, the intestine cannot secrete hormones and enzymes normally, and thus, proper intestinal function cannot be maintained[4,5]. Thus far studies have pointed out that the mechanism potentially responsible for causing change in the nonfunctional segment of the colon is "disuse" since disuse atrophy occurs when limbs and organs remain nonfunctional for a long period[6]. However, different degrees of disuse atrophy of the colon have been observed clinically, which are accompanied by colitis and other symptoms[7,8]. This condition, called diversion colitis, was first described by Glotzer et al[9] in 1981. Diversion colitis is characterized by nonspecific mucosal inflammation. Its main clinical manifestations include intestinal bleeding, tenesmus, mucous discharge, and abdominal pain. The pathogenesis of this condition is unclear. A majority of the researchers think it is related to the nutritional deficiency of certain factors occurring in the colon, especially that of the short-chain fatty acids[10,11].

Available evidence suggests that this atypical symptom condition usually occurs in the early stage of the colonic exclusion, because after restoring the intestinal continuity, this colitis was noted to have resolved[2,12]. However, in some cases, inflammatory lesions persist or even develop further as a continuation of the morphological and molecular changes in the colonic mucosa. The inflammation continues to worsen as the diversion is maintained for a longer duration. Repeated cycles of tissue damage and regeneration occur, leading to intestinal bleeding, necrosis, and granulation tissue proliferation[13].

Several factors that affect colonic metabolism and microflora, including defects in the intestinal barrier function, alterations in butyrate oxidation, or increased production of free oxygen radicals, seem to contribute to the inflammatory process[14]. However, there is a lack of knowledge regarding the exact mechanisms underlying the complex pathology of intestinal tract inflammation. Therefore, in our patient, the most likely explanation for this condition is that the inflammatory exudate and mucus in the colon were probably not absorbed and discharged in time after the colon was closed, and eventually they accumulated to form a large amount of pus.

Our case highlights the following: (1) We should be more cautious with the surveillance of the patients with indwelling intestines, and ensure long-term follow-up, regular review of colonoscopy, and timely symptomatic treatment; (2) The surgical approach of sealing both ends of the colon for long-term exclusion is uncommon in clinical practice. This should only be done in case of emergency surgery or in exceptional cases. When both ends of the colon are sealed, regular surveillance with colonoscopy is not possible, and oral drugs and enema/suppositories cannot be used. Therefore, caution should be exercised when selecting this surgical approach; and (3) Indwelling intestines will continue to cause problems for the patients and the surgeons. Colostomy is maintained in many patients for a long period, and in some patients, the reconstruction of intestinal continuity might not be possible[15]. Limited by a paucity of studies investigating the patients with long-term indwelling intestines, we cannot arrive at a reliable conclusion, but it is likely that a solution may soon emerge from current clinical observations and further research.

Even though, colonic exclusion is routinely performed, this report aimed to increase awareness regarding the long-term complications of indwelling colon after digestive tract reconstruction.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chien SC, Teragawa H S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Wu SW, Ma CC, Yang Y. Role of protective stoma in low anterior resection for rectal cancer: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:18031-18037. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Roediger WE. The starved colon--diminished mucosal nutrition, diminished absorption, and colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33:858-862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Greenwood-Van Meerveld B, Johnson AC, Grundy D. Gastrointestinal Physiology and Function. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2017;239:1-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kobayashi M, Khalil HA, Lei NY, Wang Q, Wang K, Wu BM, Dunn JCY. Bioengineering functional smooth muscle with spontaneous rhythmic contraction in vitro. Sci Rep. 2018;8:13544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ritchie JA. Colonic motor activity and bowel function. I. Normal movement of contents. Gut. 1968;9:442-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Williamson RC. Disuse atrophy of the intestinal tract. Clin Nutr. 1984;3:169-170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Landerholm K, Wood C, Bloemendaal A, Buchs N, George B, Guy R. The rectal remnant after total colectomy for colitis - intra-operative,post-operative and longer-term considerations. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:1443-1452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | de Oliveira-Neto JP, de Aguilar-Nascimento JE. Intraluminal irrigation with fibers improves mucosal inflammation and atrophy in diversion colitis. Nutrition. 2004;20:197-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Glotzer DJ, Glick ME, Goldman H. Proctitis and colitis following diversion of the fecal stream. Gastroenterology. 1981;80:438-441. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Kabir SI, Kabir SA, Richards R, Ahmed J, MacFie J. Pathophysiology, clinical presentation and management of diversion colitis: a review of current literature. Int J Surg. 2014;12:1088-1092. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Whelan RL, Abramson D, Kim DS, Hashmi HF. Diversion colitis. A prospective study. Surg Endosc. 1994;8:19-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Szczepkowski M, Kobus A, Borycka K. How to treat diversion colitis? Acta Chir Iugosl. 2008;55:77-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Szczepkowski M, Banasiewicz T, Kobus A. Diversion colitis 25 years later: the phenomenon of the disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2017;32:1191-1196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Son DN, Choi DJ, Woo SU, Kim J, Keom BR, Kim CH, Baek SJ, Kim SH. Relationship between diversion colitis and quality of life in rectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:542-549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Szczepkowski M, Banasiewicz T, Krokowicz P, Dziki A, Wallner G, Drews M, Herman R, Lorenc Z, Richter P, Bielecki K, Tarnowski W, Kruszewski J, Kładny J, Głuszek S, Zegarski W, Kielan W, Paśnik K, Jackowski M, Wyleżoł M, Stojcev Z, Przywózka A. Polish consensus statement on the protective stoma. Pol Przegl Chir. 2014;86:391-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |