Published online Jul 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i19.5217

Peer-review started: January 4, 2021

First decision: April 29, 2021

Revised: May 1, 2021

Accepted: May 17, 2021

Article in press: May 17, 2021

Published online: July 6, 2021

Processing time: 170 Days and 15.2 Hours

Leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata (LPD) is a rare condition characterized by multiple pelvic and abdominal nodules, which are composed of smooth-muscle cells. To date, no more than 200 cases have been reported. The diagnosis of LPD is difficult and there are no guidelines on the treatment of LPD. Currently, surgical excision is the mainstay. However, hormone blockade therapy can be an alternative choice.

A 33-year-old female patient with abdominal discomfort and palpable abdominal masses was admitted to our hospital. She had undergone four surgeries related to uterine leiomyoma in the past 8 years. Computed tomography revealed multiple nodules scattered within the abdominal wall and peritoneal cavity. Her symptoms and the result of the core-needle biopsy were consistent with LPD. The patient refused surgery and was then treated with tamoxifen, ulipristal acetate (a selective progesterone receptor modulator), and goserelin acetate (a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist). Both tamoxifen and ulipristal acetate were not effective in controlling the disease progression. However, the patient achieved an excellent response when goserelin acetate was attempted with relieved syndromes and obvious shrinkage of nodules. The largest nodule showed a 25% decrease in the sum of the longest diameters from pretreatment to posttreatment. Up to now, 2 years have elapsed and the patient remains asymptomatic and there is no development of further nodules.

Goserelin acetate is effective for the management of LPD. The long-term use of goserelin acetate is thought to be safe and effective. Hormone blockade therapy can replace repeated surgical excision in recurrent patients.

Core Tip: Goserelin acetate is effective for the long-term management of leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminate (LPD) and can be an alternative when leuprolide acetate is not available. Repeated surgical excision in LPD cases should be carefully considered. Tamoxifen and ulipristal acetate may not be effective in treating LPD.

- Citation: Yang JW, Hua Y, Xu H, He L, Huo HZ, Zhu CF. Treatment of leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata with goserelin acetate: A case report and review of the literature. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(19): 5217-5225

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i19/5217.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i19.5217

Leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminate (LPD), also referred to as disseminated peritoneal leiomyomatosis (DPL), is a rare disease characterized by multiple benign nodules scattered over the pelvis and peritoneal cavity, which was first described in 1952[1]. LPD comprises one of three kinds of uterine smooth-muscle tumors with unusual growth patterns whose histology is similar to uterine leiomyoma (UL). The other types are intravenous leiomyomatosis (IVL) and benign metastasizing leiomyoma (BML)[2]. To date, no more than 200 cases have been reported, the majority of which are women of reproductive age[3]. Due to the low prevalence rate, there is a lack of consensus on the standard treatment for LPD. The mainstay of treatment is surgery. In addition, hormone blockade treatment is an appropriate choice.

We report herein successful long-term management of LPD with goserelin acetate (Zoladex). The timeline of the patient is shown in Table 1. Goserelin acetate can be an alternative option for conservative long-term treatment of LPD. Related articles are also reviewed. We performed a search of MEDLINE and Google Scholar using the keywords LPD and DPL.

| Event | Date |

| Hospitalization | January 2018 |

| Laboratory results and Imaging examinations | January 2018 |

| Tamoxifen | January 2018 to July 2018 |

| Goserelin acetate | July 2018 to February 2019 |

| Ulipristal acetate | February 2019 to June 2019 |

| Goserelin acetate | June 2019 to Now |

A 33-year-old Chinese female patient (G1P1) was admitted to our hospital for abdominal discomfort, pelvic pain, and palpable abdominal masses in January 2018.

The patient felt intermittent abdominal discomfort 8 mo ago. At that time, there were no other discomforts including abdominal pain or bloating, so she did not pay much attention. However, in the past 4 mo, she felt pelvic pain and touched a lower abdominal mass. The size of the mass slowly increased, and the symptoms of abdominal discomfort and pelvic pain became more and more serious.

The past medical history was notable for four surgeries because of UL without morcellation from 2007 to 2015. The details are summarized in Table 2.

| Date | Surgery procedure | Disease | Number and volume of nodules | Location of fibroids | Pathological examination |

| December 2007 | Abdominal myomectomy | UL | One, diameter 5 cm | Uterine wall | UL |

| May 2010 | Abdominal myomectomy | UL | Two, diameter 8 cm | Uterine wall | UL |

| June 2012 | Abdominal myomectomy and cesarean section | UL, fetal distress | Multiple, the biggest one was 8 cm in diameter | Right uterine wall | UL |

| April 2015 | Total hysterectomy, myomectomy and slapingectomy | Multiple UL | Several nodules, the biggest one was 10 cm in diameter | Uterine wall and peritoneal cavity | Spindle-shaped smooth muscle cell tumor |

The patient denied any family history of UL or LPD and previous oral contraceptive (OC) use.

On abdominal examination, an 8 cm × 8 cm fist-sized palpable right lower-quadrant near midline anterior abdomen mass was observed. There was no tenderness or rebound tenderness.

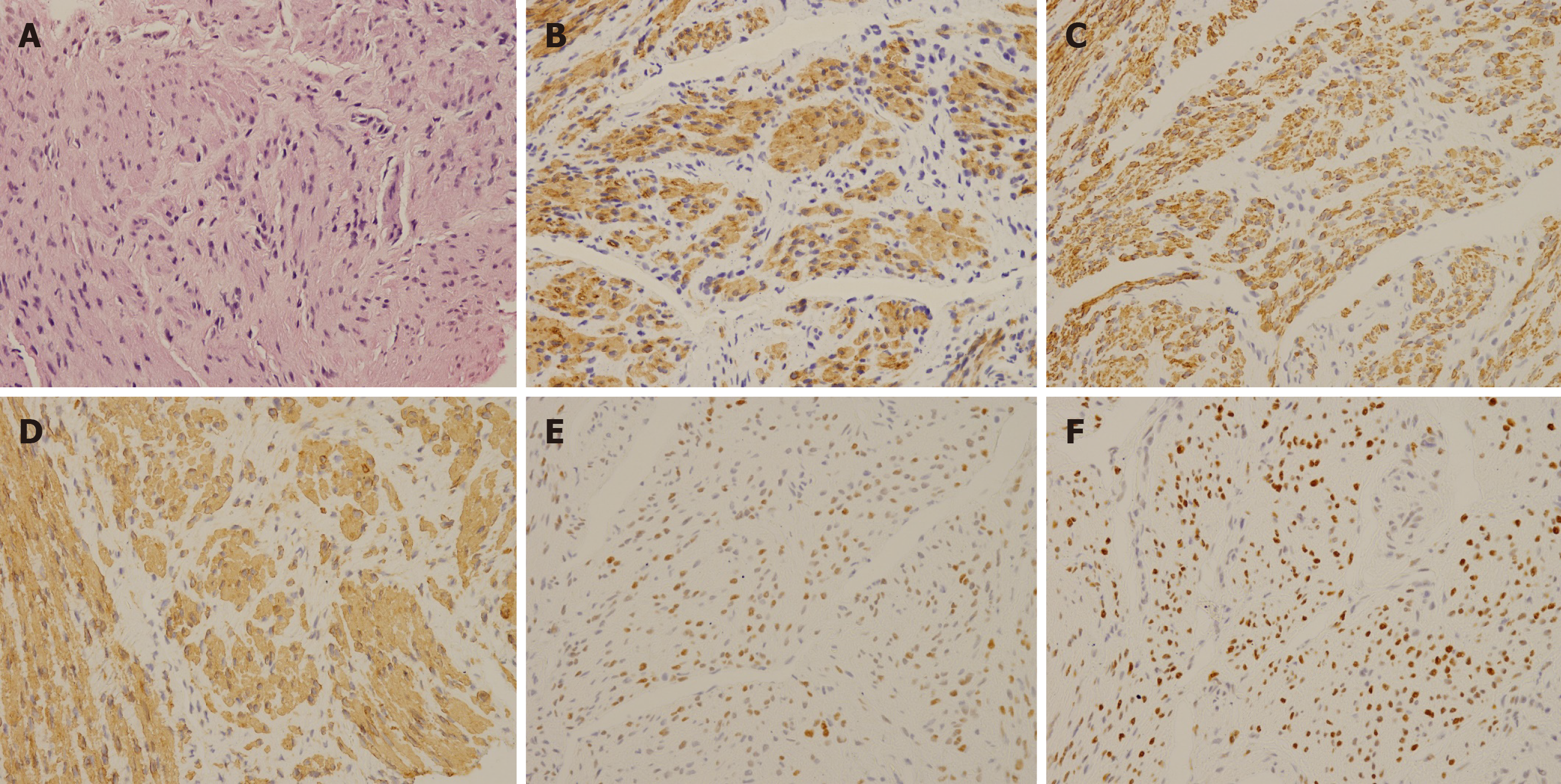

Laboratory testing including tumor markers, sex hormones, and other tests yielded normal results. The pathology of the core-needle biopsy showed a spindle-shaped smooth-muscle cell tumor with features of leiomyoma without necrosis and atypia. Immunohistochemistry staining was positive for Caldesmon, smooth-muscle actin (SMA), Desmin, estrogen receptors (ERs), and progesterone receptors (PRs) but negative for SOX-10, and CD117 (Figure 1), and the Ki-67 index was 5%.

Whole exon sequencing of 120 cancer-related genes by next-generation sequencing for determining the possibility of malignant transformation was also performed. However, no germline variants were found.

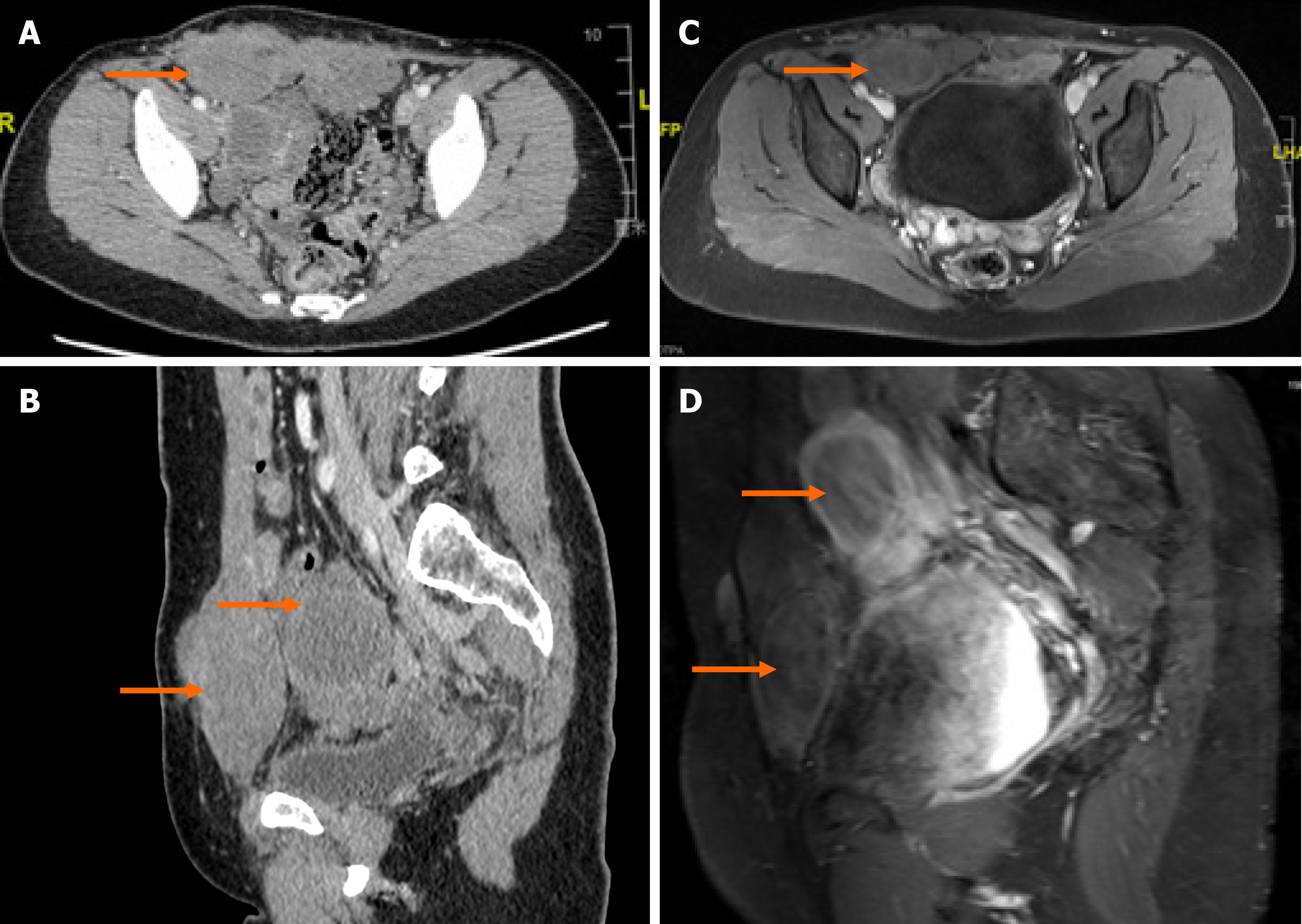

Computed tomography confirmed multiple nodules involving the abdominal wall and pelvic cavity ranging from 3-7 cm in diameter, in which the largest nodule was approximately 78 mm × 66 mm × 40 mm. No distant metastasis or intravenous proliferation was found (Figures 2A, 2B and 3A).

Caldesmon, SMA, and Desmin are three markers characteristically found in smooth muscle cells, which can distinguish UL or leiomyosarcoma. SOX-10 expression can be found in myoepithelial neoplasms. CD117 is typically positive in gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST). These markers helped eliminate potential differential diagnoses and determine the diagnosis of leiomyomatosis. No distant metastasis or intravenous proliferation excluded the diagnosis of BML and IVL.

The patient was diagnosed with LPD according to clinical symptoms and pathological characteristics.

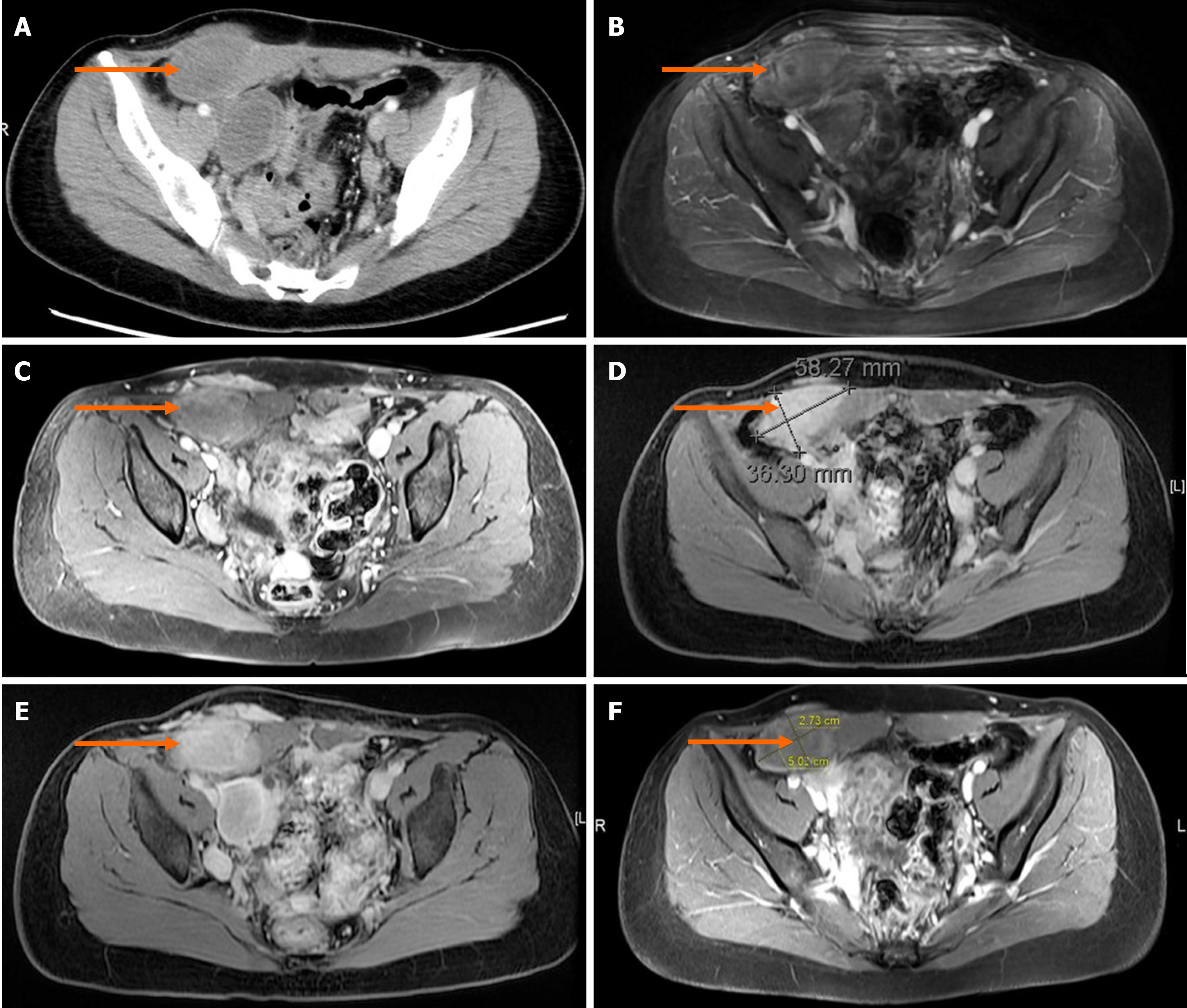

The patient refused to undergo surgery again. Individual conservative treatments were then tailored to her situation. A 6-mo trial of tamoxifen [a selective ER modulator, (SERM)] (20 mg/d) was attempted with the goal of estrogen blockade because of ER positivity. However, tamoxifen did not prevent nodule progression. In July 2018, the symptoms worsened and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) detected obvious enlargement of the nodules (Figure 3B). Immediately, her therapy was changed to goserelin acetate (Zoladex, 3.6 mg/28 d) with satisfactory results. The reason why we chose goserelin acetate instead of leuprolide acetate is that leuprolide acetate was not available in our department at that time. Obvious regression of nodule volume was noted on MRI and the patient's symptoms also decreased (Figure 3C). In February 2019, after considering the high cost of goserelin acetate and the risk of calcium deficiency, the patient accepted ulipristal acetate (Esyma) (5 mg/d) despite the paucity of successful evidence for this treatment. Ulipristal acetate was stopped after 3 mo as recommended by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) to minimize the risk of serious liver injury. However, neither an obvious decrease nor progression in tumor burden was detected on MRI in June 2019 (Figure 3D). Finally, the patient reaccepted goserelin acetate (Zoladex, 3.6 mg/28 d) and again had an excellent symptomatic and radiologic response to this treatment. MRI confirmed that both the numbers and volumes of the nodules were decreased, and the largest nodule shrunk to 65 mm × 50 mm × 26 mm by December 2019 (Figures 2C, 2D, and 3E).

In October 2020, in regular follow-up, the patient remained asymptomatic and MRI also confirmed a continuous shrinkage of the biggest nodule (Figure 3F). The largest nodule showed a 25% decrease in the sum of the longest diameters from pretreatment (January 2018) to posttreatment (October 2020) (Figure 3A and F).

Some LPD patients are asymptomatic, while others may have various symptoms, including abdominal pain and pelvic compression. The diagnosis is difficult because of these nonspecific symptoms. The final diagnosis of LPD must include histological and immunohistochemical examinations to distinguish it from IVL, BML, uterine leiomyosarcoma, or GIST[4,5].

The etiology of LPD remains controversial and includes two main theories: Iatrogenic theory and hormone theory. The iatrogenic theory hypothesizes that LPD is caused by the iatrogenic spread of UL because of morcellation during myomectomy. The morcellation of UL can leave small fragments of original myomas which result in LPD[6]. The results of cytogenetic analysis support this theory. Miyake et al[7] reported that current LPD was the monoclonal metastasis from the previously resected UL because of an identical nonrandom-X-chromosome inactivation pattern. Ordulu et al[8] reported characteristic chromosomal abnormalities found in both current LPD and previous UL samples, indicating that current LPD may result from the seeding of UL cells during the previous surgery. However, cases of LPD without morcellation or a history of UL have also been reported[6], which make this theory less convincing.

Another theory, the hormone theory, postulates that LPD nodules may derive from the metaplastic change of mesenchymal stem cells into myocytes due to the stimulation of high levels of female sex hormone[6]. Normally, most LPD cases are endogenous (e.g., pregnancy or steroid-hormone secreting ovarian tumors) or exogenous (e.g., hormone replacement therapy or OC) hormonal stimulus-related[9,10]. And, according to the result of immunohistochemistry staining, most excised LPD lesions are ER-, PR-, or luteinizing hormone receptor-positive, which indicates that sex hormones may play an important role in the progression of these nodules[11,12]. Fujii et al[13] successfully reproduced nodules similar to LPD after administering high doses of sex hormones in guinea pigs.

There are no guidelines for the treatment of LPD. Individualized treatments should be based on the patients’ age, reproductive desire, and the severity of symptoms[14]. Currently, surgical excision is the mainstay of treatment, which can provide immediate symptom palliation. Surgical procedures should be determined according to the location of the nodules and the patients’ age. For patients who have no desire for fertility or are postmenopausal, hysterectomy and oophorectomy may be added[15,16]. However, the excision of all disseminated nodules during surgery is challenging and patients are subject to long-term postoperative sequelae[17]. In addition, there is a high risk of recurrence after surgery. Most cases reported no recurrence, possibly because patients were followed for only 6 mo at the time when researchers reported the cases. However, 6 mo of follow-up seems to be too short to confirm recurrence, which may lead to an incorrect recurrence rate. Case reports of disease recurrence a few years after surgery are not rare. Of note, Lin et al[18] reported recurrence 5 years after surgery. The mechanisms of recurrence remain unknown. Quaranta et al[19] hypothesized that micro-metastasis is the basis of recurrent nodules. In studies of UL, Hanafi[20] and Nishiyama et al[21] reported that patients with a single leiomyoma had a lower probability of recurrence than patients with multiple leiomyomas. Radosa et al[22] reported that cumulative recurrence increased steadily after primary surgery. We may infer that the probability of LPD recurrence may be also related to the numbers of nodules and previous surgeries. Therefore, we suggest that repeated surgery should be avoided among LPD patients with multiple scattered nodules, especially in recurrent cases.

For patients who are not suitable for or refuse surgery, hormone blockade therapy is an alternative. Due to the positive expression of hormone receptors in LPD nodules, hormone blockade with simple or a combination of SERM/selective progesterone receptor modulator (SPRM), aromatase inhibitors (AI), and gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist (GnRH-a) has been attempted. Takeda et al[23] and Ando et al[24] reported the antiproliferative effect and long-term safety of anastrozole (an AI). GnRH-a has also been attempted owing to its ability to suppress ovarian steroidogenesis and inhibit the conversion of androgens to estrogens. Hales et al[25] reported notable regression of LPD nodules after administration of leuprolide acetate (a GnRH-a) for 6 mo. Moreover, Verguts et al[26] and Benlolo et al[27] suggested that ulipristal acetate (a SPRM) is a novel and more promising treatment option than GnRH-a with fewer side effects despite a lack of proven long-term safety. In addition, for patient with hormone-unresponsive status, Lin et al[18] reported that systemic chemotherapy can also be effective.

In this case, we inferred that hormone stimulation played a more important role in the pathogenesis of our patient after considering the fact that the patient had no history of morcellation, the positive expression of hormone receptors, and the negative result of genetic testing. Therefore, hormone blockade therapy was chosen. Tamoxifen was attempted due to ER positivity. However, it was insufficient to block the development of LPD, which may be explained by Bayya et al[28], who found that tamoxifen might promote the growth of extrauterine leiomyomas. In addition, Takeda et al[23] reported that raloxifene (a SERM) is insufficient to control LPD. Therefore, we speculate that SERMs may not be suitable for first-line therapy for LPD due to their paradoxical estrogenic agonist property. Ulipristal acetate treatment ended in stable disease, with no obvious decrease nor progression in tumor burden. Ulipristal acetate was stopped after 3 mo, as the EMA recommended this measure to prevent serious liver injury at the time[29]. Of note, only goserelin acetate, a GnRH-a used to treat breast cancer, prostate cancer, and endometriosis, led to satisfactory results with symptom relief and obvious continuous shrinkage of nodules in spite of the off-label use of this drug. The reason why we chose goserelin acetate is mentioned above. The standard dosage of goserelin acetate for breast cancer is 3.6 mg/28 d for 3 to 5 years. Therefore, goserelin acetate seems to be much safer than ulipristal acetate. Currently, the EMA recommends to stop taking 5 mg ulipristal acetate since March 13, 2020 because of recent cases of liver injury[30]. Informed consent was obtained from the patient for off-label medicine use, publication of this case report and any accompanying images, and use of her data in accordance with the ethical standards of our institutional ethics committee. We performed a search of MEDLINE and Google Scholar for the period from inception to October 2020 using the keywords ‘LPD’, ‘DPL’, and ‘goserelin acetate’. Four related case reports were found and are summarized in Table 3. Verguts et al[26] first reported successful control of LPD through goserelin acetate treatment in a 21-year-old woman, but this drug also caused side effects (menorrhagia and ovarian cysts). Nassif et al[31] reported the quasi-disappearance of all LPD nodules after a 6-mo goserelin acetate therapy with no side effects and the LPD had not recurred for 1 year. Quaranta et al[19] reported a case in which goserelin acetate was used in a 60-year-old woman, but the LPD recurred in one year. Ando et al[24] used goserelin acetate for preoperative preparation and found that the LPD nodules regressed but remained in the pelvic cavity. The information from these pieces of literature suggests that goserelin acetate might have a role in the treatment of LPD. To further determine a more precise treatment and the role of goserelin acetate, more studies and longer follow-up are necessary in the future.

| Case No. | Ref. | Age | Obstetric history | UL history; treatments | OC use/HRT | Symptoms | ER/PR status | Treatments | Response |

| 1 | Verguts et al[26], 2014 | 21 | Unknown | Yes; hysteroscopic resection | No/No | Abdominal discomfort | Negative/positive | Goserelin acetate and tibolone × 2 yr → ulipristal acetate × 1 yr | +, + |

| 2 | Nassif et al[31], 2016 | 45 | G1P1 | Yes; unknown | Yes/No | Dorsal pain | Positive/unknown | Goserelin acetate × 6 mo → Progestin × 6 mo | +, treatment for UL |

| 3 | Quaranta et al[19], 2018 | 60 | P3 | Yes; unknown | No/No | Abdominal discomfort and postmenopausal bleeding | Strongly positive/strongly positive | Goserelin acetate | LPD recurred within one year |

| 4 | Ando et al[24], 2017 | 40 | G0 | Yes; transcervical resection | No/No | Abdominal pain | Slightly positive/slightly positive | Goserelin acetate 1.8 mg monthly × 6 mo → TAH, BSO and tumor resection → letrozole | +, LPD recurred 6 mo after surgery, + |

In conclusion, LPD is a rare disease characterized by multiple benign nodules scattered over the surface of the pelvis and peritoneal cavity. There are no guidelines on the treatment of LPD. Individualized treatments should be based on the patient’s own situation. Currently, surgical excision is the mainstay of treatment. However, we found that goserelin acetate was effective for the management of LPD. So, long-term conservative treatment of LPD with GnRH-a may be a better choice in LPD patients who have experienced several previous surgeries, LPD recurrence, or multiple unresectable nodules. Repeated surgical resection in LPD cases should be carefully considered.

We would like to thank all members in our department and my friends Wang YQ and Chen YF for their helpful suggestions and language help. Great thanks to Hua Y and best wish to your love and PhD journey. Thanks to Yui A and Cui Y who gave me powerful spiritual support when I wrote this case report.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: García Cabrera AM S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Ferrario L, Zerbi P, Angiolini MR, Agarossi A, Riggio E, Bondurri A, Danelli P. Leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata: A case report of recurrent presentation and literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;49:25-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Vaquero ME, Magrina JF, Leslie KO. Uterine smooth-muscle tumors with unusual growth patterns. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009;16:263-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Xu S, Qian J. Leiomyomatosis Peritonealis Disseminata with Sarcomatous Transformation: A Rare Case Report and Literature Review. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2019;2019:3684282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Xiao J, Zhang R, Teng Y, Liu B. Disseminated peritoneal leiomyomatosis following laparoscopic myomectomy: a case report. J Int Med Res. 2019;47:5301-5306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Psathas G, Zarokosta M, Zoulamoglou M, Chrysikos D, Thivaios I, Kaklamanos I, Birbas K, Mariolis-Sapsakos T. Leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata: A case report and meticulous review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2017;40:105-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Li J, Dai S. Leiomyomatosis Peritonealis Disseminata: A Clinical Analysis of 13 Cases and Literature Review. Int J Surg Pathol. 2020;28:163-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Miyake T, Enomoto T, Ueda Y, Ikuma K, Morii E, Matsuzaki S, Murata Y. A case of disseminated peritoneal leiomyomatosis developing after laparoscope-assisted myomectomy. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2009;67:96-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ordulu Z, Dal Cin P, Chong WW, Choy KW, Lee C, Muto MG, Quade BJ, Morton CC. Disseminated peritoneal leiomyomatosis after laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy with characteristic molecular cytogenetic findings of uterine leiomyoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2010;49:1152-1160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yuri T, Kinoshita Y, Yuki M, Yoshizawa K, Emoto Y, Tsubura A. Leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata positive for progesterone receptor. Am J Case Rep. 2015;16:300-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Heinig J, Neff A, Cirkel U, Klockenbusch W. Recurrent leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata after hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy during combined hormone replacement therapy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2003;111:216-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Butnor KJ, Burchette JL, Robboy SJ. Progesterone receptor activity in leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1999;18:259-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Danikas D, Goudas VT, Rao CV, Brief DK. Luteinizing hormone receptor expression in leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:1009-1011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fujii S, Nakashima N, Okamura H, Takenaka A, Kanzaki H, Okuda Y, Morimoto K, Nishimura T. Progesterone-induced smooth muscle-like cells in the subperitoneal nodules produced by estrogen. Experimental approach to leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;139:164-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lee WY, Noh JH. Leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata associated with appendiceal endometriosis: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2015;9:167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wu C, Zhang X, Tao X, Ding J, Hua K. Leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata: A case report and review of the literature. Mol Clin Oncol. 2016;4:957-958. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yang R, Xu T, Fu Y, Cui S, Yang S, Cui M. Leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata associated with endometriosis: A case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2015;9:717-720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tan HL, Koh YX, Chew MH, Wang J, Lim JSK, Leow WQ, Lee SY. Disseminated peritoneal leiomyomatosis: a devastating sequelae of unconfined laparoscopic morcellation. Singapore Med J. 2019;60:652-654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lin YC, Wei LH, Shun CT, Cheng AL, Hsu CH. Disseminated peritoneal leiomyomatosis responds to systemic chemotherapy. Oncology. 2009;76:55-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Quaranta M, Mehra G, Nath R, Culora G, Sayasneh A. A rare case of refractory disseminated leiomyomatosisperitonealis complicated by cauda equina compression. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018;229:205-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hanafi M. Predictors of leiomyoma recurrence after myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:877-881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Nishiyama S, Saito M, Sato K, Kurishita M, Itasaka T, Shioda K. High recurrence rate of uterine fibroids on transvaginal ultrasound after abdominal myomectomy in Japanese women. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2006;61:155-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Radosa MP, Owsianowski Z, Mothes A, Weisheit A, Vorwergk J, Asskaryar FA, Camara O, Bernardi TS, Runnebaum IB. Long-term risk of fibroid recurrence after laparoscopic myomectomy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;180:35-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Takeda T, Masuhara K, Kamiura S. Successful management of a leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata with an aromatase inhibitor. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:491-493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ando H, Kusunoki S, Ota T, Sugimori Y, Matsuoka S, Ogishima D. Long-term efficacy and safety of aromatase inhibitor use for leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2017;43:1489-1492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hales HA, Peterson CM, Jones KP, Quinn JD. Leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata treated with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist. A case report. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167:515-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Verguts J, Orye G, Marquette S. Symptom relief of leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata with ulipristal acetate. Gynecol Surg. 2014;11:57-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Benlolo S, Papillon-Smith J, Murji A. Ulipristal Acetate for Disseminated Peritoneal Leiomyomatosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:434-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Bayya J, Minkoff H, Khulpateea N. Tamoxifen and growth of an extrauterine leiomyoma. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008;141:90-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | European Medicines Agency. Esmya: new measures to minimise risk of rare but serious liver injury. [cited 5 December 2020]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/referrals/esmya. |

| 30. | European Medicines Agency. PRAC recommends revoking marketing authorisation of ulipristal acetate for uterine fibroids. [cited 5 December 2020]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/referrals/ulipristal-acetate-5mg-medicinal-products. |

| 31. | Nassif GB, Galdon MG, Liberale G. Leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata: case report and review of the literature. Acta Chir Belg. 2016;116:193-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |