INTRODUCTION

Fear of missing out (FoMO) is a unique term introduced in 2004 and then extensively used since 2010[1] to describe a phenomenon observed on social networking sites. It eventually made it to the oxford dictionary in 2013[2]. In 2013[3] British psychologists elaborated and defined it as “pervasive apprehension that others might be having rewarding experiences from which one is absent”, FoMO is characterized by the desire to stay continually connected with what others are doing. FoMO was conceptualized using self-determination theory (SDT), which was developed by Ryan et al[4] and applied by Przybylski et al[3] to understanding what drives FOMO. In SDT[5], social relatedness can drive intrinsic motivation, which in turn can encourage positive mental health. Przybylski et al[3] applied SDT to FoMO, proposing that FoMO is a negative emotional state resulting from unmet social relatedness needs. The conceptualization that FoMO involves negative affect from unmet social needs is similar to theories about the negative emotional effects of social ostracism[6]. FoMO is a relatively new psychological phenomenon. It may exist as an episodic feeling that occurs in mid-conversation, as a long-term disposition, or a state of mind that leads the individual to feel a deeper sense of social inferiority, loneliness, or intense rage[7].Today, more than ever, people are exposed to a lot of details about what others are doing; and people are faced with the continuous uncertainty about whether they are doing enough or if they are where they should be in terms of their life[8]. FoMO includes two processes; firstly, perception of missing out, followed up with a compulsive behavior to maintain these social connections. The social aspect of FoMO could be postulated as relatedness which refers to the need to belong, and formation of strong and stable interpersonal relationships[9]. FoMO is considered as a type of problematic attachment to social media, and is associated with a range of negative life experiences and feelings, such as a lack of sleep, reduced life competency, emotional tension, negative effects on physical well-being, anxiety and a lack of emotional control; with intimate connections possibly being seen as a way to counter social rejection[10]. In the last seven years research is done to establish its links with various mental health outcomes. We are interested in understanding which population is more vulnerable to this phenomenon. It is also unclear which reward pathway seems to be involved in its reinforcing effects. It has been widely accepted that dopaminergic tracts, in particular, mesolimbic systems get activated with successful social connections[11]. The reward prediction error encoding and variable reward schedules are known to maintain these behaviors. FoMO is not a unitary phenomenon, but rather a more complex construct that could reflect a certain personal predisposition and maintained by rewarding experiences that results from people’s desire for interpersonal attachments.

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

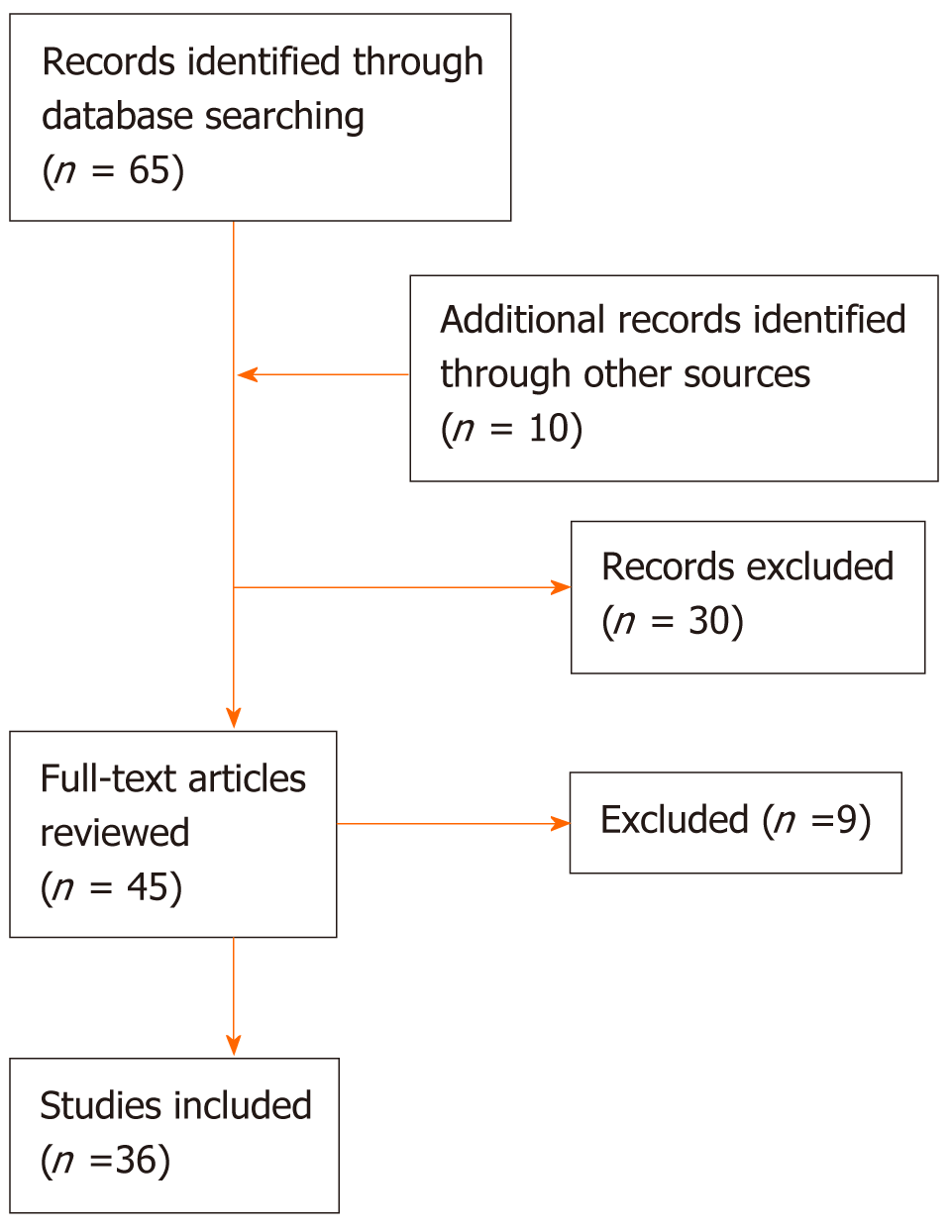

This paper provides a general review of the literature. A literature search was conducted in PubMed, Google Scholar databases with coverage from January 2002 to December 2020. The search terms included “FoMO,” “depression,” “anxiety,” “sleep,” “academic” and “physical well-being.” Results were restricted to peer-reviewed English-language articles. Conference and dissertation proceedings, case reports, protocol papers and opinion pieces were excluded. Reference lists were examined for additional articles of relevance. We identified n = 65 articles according to the above search methods. An additional 10 articles were identified through hand search and Google Scholar articles. Total n = 30 was excluded according to abstract screening. Full text review was performed for n = 45 articles according to study inclusion criteria. The n = 9 articles failed to meet stated inclusion criteria. Figure 1 shows the flowchart for study selection for inclusion.

Figure 1 The flowchart for study selection for inclusion.

FOMO AND MENTAL HEALTH

Social networking sites (SNS) provides a compensatory medium for adolescents with social anxiety[12] to address their unmet social needs in a manner other than face to face communication[13]. The use of SNS contributes to easier communication[14] for those with deficits by compensating for their unmet social needs with much less effort and instantaneously[15,16]. However, this “social compensation” can be problematic when it reinforces avoidance for face-to-face and consequentially increasing social anxiety[17]. These processes likely to worsen social fears and predisposes one for anxiety disorders. FoMO is also associated with problematic SNS use due to its easy access for adolescents to interact at will[18,19] and constant need for personal validation and rewarding appraisals of distorted sense of self[20]. FoMO cognitive aspect is manifested by negative ruminations like frequently checking and refreshing SNS for alerts and notifications. These subsequently heightens the levels of anxiety in order to keep up with the theme with anticipation of a reward[21]. The concept of FoMO explores the fear of social exclusion. Through social media, there is continuous awareness of what an individual may be missing in terms of a good time which researcher phrases as “it creates distorted perceptions of edited lives of others”. The ‘Round the clock’ nature of these communication may lead to feeling lonely and inadequate through highlighting others activities and popularity and comparison of oneself to others, leading to vicious cycle of compulsive checking and engagement. FoMO has a relationship with the amount time spent on SNS as a predictor of emotional distress[22]. The constant “upward social comparisons” and unreasonable expectations can adversely impact one’s self-esteem. These events are associated with emergence of depressive symptoms in some individuals[23]. These depressive symptoms may be further compounded by perceptions that one can avoid negative emotions when part of these online communities[24]. In a Belgian[25] study with 1000 subjects, 6.5% were found to be using SNSs excessively, they were found to have lower emotional stability and agreeableness, conscientiousness, perceived control and self-esteem which could be risk factor for affective disorders. The problematic use of internet and development of FoMO is associated with young adults ignoring peer relationships, potentially leading to depressive symptoms[26]. Additionally, the longer time spent using SNS (spending more than 2 h per day) demonstrated a significantly higher risk of having suicidality[27]. FOMO may have a mediational role between narcissism and problematic SNS use suggesting that unmet social relatedness needs cause high engagement in problematic SNS use[28,29]. A constant need for rewarding experiences reinforces one with FoMO to engage in risky activities[30] to maximize socialization opportunities[3]. FoMO has been associated with negative alcohol-related consequences either through higher alcohol use or greater willingness to engage in higher risk behaviors[31]. Adolescents with FoMO may likely to experiment with drugs and alcohol[32] to fit in with peers on SNS.

FOMO AND SOCIAL FUNCTIONING

Despite the instantaneous and desired interactions with peers via social media, young adults are feeling lonelier and more disconnected than ever[33]. FoMO may exacerbate pre-existing feelings of loneliness after engaging on SNSs extensively[34]. It is argued that communication channels with fewer nonverbal cues may result in less warmth and closeness among those who are interacting in verbal means, avoiding meaningful and pragmatic communication[35]. This may result in misinterpretations and misunderstanding leading to further emotional dissatisfaction and feelings of loneliness[36]. It is believed that time spent on social networking sites, activates the amygdala and the fear pathway, rendering young adults vulnerable to feelings of loneliness, and social disconnectedness[3]. This contributes to a cyclical nature[3] of FoMO where an individual engages with SNS to alleviate feelings of loneliness, but in fact exacerbates them. They have to again return to SNS and attempt to alleviate these feelings[37]. Conversely, young adults who experienced less satisfaction of the basic psychological needs for competence, autonomy, and connectedness to others, also reported higher levels of FoMO[3]. FoMO broadcasts more options than can be pursued, impacting an individual's decision making in personal and professional settings[38]. It may impair an individual’s ability to make commitments and agreements, as one feels inclined to keep options open and not risk losing out on an important, potentially life-changing experience which may offer greater meaning and personal gratification.

FOMO AND RELATIONSHIP WITH SLEEP

The FoMO and interpersonal stress are associated with insomnia and subsequently poor mental health outcomes[39]. In another Chinese study of university students, researchers found negative affect, which is “a general dimension of subjective distress and unpleasurable engagement that subsumes a variety of aversive mood states, including anger, contempt, disgust, guilt, fear, and nervousness”, was linked with poor sleep mediated by FoMO[40]. In an Israeli university study of 40 participants who measured smartphone use at night, were at risk of reduced sleep quality and overall psychological health[41]. A survey of 101 adolescents linked pre-sleep worry and FoMO to longer sleep onset latency and reduced sleep duration[42]. It is also well established in clinical research, the blue light emitting from the screen of the electronic devices (short-wave blue light with wavelength between 415 nm and 455 nm) affect sleep[43]. The postulated mechanism includes suppression of pineal hormone melatonin leading to a state of neuropsychological arousal. These alterations in circadian rhythm may lead to increased sleep latency, reduced sleep duration, and increased daytime sleep.

ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE AND PRODUCTIVITY

FoMO is closely related to SNS use and has negative effects on academic performance[44].The effects of problematic internet usage (PIU) and responding to frequent notifications entails repeated switching between tasks. This affects attention span; interrupts work and overall productivity[45]. The constant connection via smartphones can impair cognitive abilities and cause academic distractions. Furthermore, rapid switching between tasks is related to poor learning[46]. It is established multitaskers make more mistakes and take longer to complete tasks[47]. Additionally, overuse of SNS has been associated with decreased academic performance and activity[48].

FOMO AND NEURODEVELOPMENTAL DISORDERS

There were no current studies which link patients who have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) with FoMO. However, it will be of interest to study children and adolescents with hyperactivity and inattention who already have delayed myelination in prefrontal cortex[49]. It could be a reasonable hypothesis based on the recent evidence, that these patients would be more vulnerable to FoMO. And subsequently have further worsening in areas of self-evaluation, self-monitoring, and the interpretation of affect in social situations[50,51]. Further research is needed in this area to explore variables likely to be affected with emergence of FoMO.

FOMO AND PHYSICAL WELLBEING

The young adults with high levels of FoMO are less likely to report their own lifestyle as healthy. The feelings of envy and social exclusion are also linked with poor eating habits[52]. Additionally, FoMO promotes high SNS use which leads to a sedentary lifestyle influencing the epidemic of obesity in young adults[53]. The amount of time spent on SNS is associated with vision issues[54] and poor attention, which is linked with accidents while walking, crossing roads, driving or doing daily activities. PIU due to FoMO may lead to poor posture and subsequent musculoskeletal pain involving neck, back and hands and fingers[55]. This is further accentuated as pain prevents the initiation or the continuation of sleep, contributing to poor physical health.

TREATMENT OPTIONS FOR FOMO

The treatment choice is based on the principles of cognitive behavior therapy (CBT)[56]. CBT addresses distorted cognitions which is postulated to be underlying its development and maintenance of these conditions[57]. It also addresses underlying anxiety and focuses on the predisposing factors[56]. The main treatment goal should be control rather than abstinence. FoMO reduction (FoMO-R)[57] is a novel promising specifically designed model aimed at building resilience by focusing on self-help literacy guide about design and appropriate use of SNS[58]. It is an active, effective user-friendly, safe alternative to anxiolytic drugs and self-help technique relying on dealing with the vicious circle model of anxiety[59]. The method associates between the context of use, fears and technical countermeasures. The effectiveness of cognitive reappraisal of anxiety has been recognized in helping people recognize and manage their digital addiction. Compulsive behaviors can be regulated using techniques such as distraction and reappraisal. Distraction avoidance techniques are also a part of FoMO-R. Excessive involvement in the targeted behaviors leading to self-reported functional impairment tends to be fairly transient for most individuals hence the excessive behaviors such as FoMO are often context-dependent, and that spontaneous recovery is frequent[60]. Individuals are also offered alternative strategies and opportunities for connecting with other people without having the feeling of missing out on something. Some studies have reported use of anxiolytics and found it helpful.

DISCUSSION

As per CDC, child and teens ages 8-18 spend an average of 7.5 h[61] on screen including Television. PIU[62] has been on the rise and its association with child and adolescent psychopathology has been well established. Since the introduction of SNS in 2008, there has been a steady rise in increased social interactions online. In 2014, the term FoMO which was initially used in marketing was formally adapted in clinical psychiatry to describe a unique phenomenon. It’s evident based on recent research that it’s a complex psychological underpinning involving cognitive, behavioral and addiction processes. FoMO may start with distorted thinking related to sense of fear of being left out from a rewarding experience. However, it is reinforced with constant responsiveness to SNS. Some research also terms these behaviors as compulsive. We continue to doubt if these behaviors are of obsessive nature, but clearly constant rechecking and browsing of SNS is hallmark. These behaviors are impairing several domains as discussed in the earlier part of this paper. We also hypothesize that the complex nature FoMO could be due to rapid change in technology in last two decades. Social[63] anthropology studies have demonstrated how SNS may be impacting social norms. However, it would be a fair argument that human cognitive processes have been lagging behind a rapidly changing technology interface. These researches are an attempt to recognize and understand origins and psychological interplay with multiple brain process. FoMO has been linked with not only distractibility, but overall decline in productivity and worse mental health outcomes. The recent studies have established association with sleep disturbances, social anxiety, clinical depression and decline in academic performance. It’s not clear who all are vulnerable to FoMO, but its observed that certainly personality traits and one with underlying mental health problems could be more affected. The measurement scale validated for FoMO has established in empirical research that these sequelae could be extremely impairing and debilitating. We did not observe any research linking FoMO with ADHD. ADHD is a disorder characterized with deficits with delayed gratification and theoretically one suffering from ADHD would not only be vulnerable but also likely to have worse overall outcomes related to FoMO. ADHD is strongly associated with internet gaming disorder[64] and we postulate that these subtypes would be more prone to aggressive outbursts. An alternative explanation of these phenomenon could be attributed to the negative feelings of envy[65]. The most accepted reasons are lack of intimacy in these interactions and having a large group on social media where one constantly finds themselves to compare oneself with others[66]. In this pool, it is likely people will experience frustration and envy from comparing oneself to others but still tempted in striving to be closer to the person of comparison[67]. These behaviors could exacerbate negative emotions such as envy, jealousy, resentment, and anxiety as well as the desire to chase social media perfection[68]. It is likely the effects will be worsened for individuals with mental health issues[69]. The knowledge of these underlying psychological processes would be crucial for providing psychoeducation and also planning individualized psychotherapy-based interventions. It’s also interesting to note that FoMO is a global phenomenon, and research evidence is present from North America, Asia, Europe and Australia which further underscores the need to understand the address. With regards to treatment, the common theme of all the research was its origin lies in the amount of screen time. After the recommended screen time is exceeded, one is more vulnerable to access information and maintain social relationships via SNS or social gaming networks. The key preventive measure remains restricting to the recommended screen time. The minimum age for using SNS is set at 13 and more legislative measures are needed to raise the age to 16. However, it has been reported that many younger children also have accounts on SNS. Parental education also has been found to be a highly effective measure to curb this. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommended Family Media Use Plan[70] has been a useful tool. Beside prevention, promising research based on transtheoretical model has been an effective. It’s interesting to note that a key feature of this intervention is making one understand how social media works.

CONCLUSION

FoMO is a now an established entity in the research community. However, many practicing clinicians are not aware or educated about it affecting their population. It’s imperative these new findings are communicated to the clinical community. Given it has both diagnostic implications and also could be a confounding variable in ones who do not respond to the treatment as usual. There is need for further research which includes prevalence studies, psychological understanding and more evidence-based prevention and treatment interventions.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Seeman MV S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang YL