Published online Jun 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i18.4866

Peer-review started: February 8, 2021

First decision: March 7, 2021

Revised: March 13, 2021

Accepted: May 7, 2021

Article in press: May 7, 2021

Published online: June 26, 2021

Processing time: 122 Days and 18.2 Hours

Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) is a rare malignant tumor of mesenchymal origin that mainly affects children. Spindle cell/sclerosing RMS (SSRMS) is even rarer. It is a new subtype that was added to the World Health Organization disease classification in 2013. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of adult SSRMS disease classification originating in the temporal muscle.

SSRMS originating in the temporal muscle of a male adult enlarged rapidly, destroyed the skull, and invaded the meninges. The tumor was completely removed, and the postoperative pathological diagnosis was SSRMS. Postoperative recovery was good and chemotherapy and radiotherapy were given after the operation. Followed up for 3 mo, no tumor recurred.

RMS is one of the differential diagnoses for head soft tissue tumors with short-term enlargement and skull infiltration. Preoperative computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging is necessary for early detection of tumor invasion of the skull and brain tissue.

Core Tip: Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) is a rare malignant tumor of mesenchymal origin that mainly affects children. Spindle cell/sclerosing RMS (SSRMS) is even rarer. We describe an adult case of SSRMS originating in the temporal muscle. The tumor rapidly enlarged, destroyed the skull, and invaded the meninges. The tumor was completely removed. The postoperative pathological diagnosis was SSRMS. This case report provides complete imaging data of tumor progression. To our knowledge, this case is the first reported adult SSRMS originating from the temporal muscle.

- Citation: Wang GH, Shen HP, Chu ZM, Shen J. Adult rhabdomyosarcoma originating in the temporal muscle, invading the skull and meninges: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(18): 4866-4872

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i18/4866.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i18.4866

Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) is a rare, highly aggressive, rapidly growing mesenchymal malignancy that is more common in children[1]. Spindle cell/sclerosing RMS (SSRMS) is even rarer. It is a new subtype that was added to the disease classification of the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2013. RMS mainly occurs in the head and neck area[2]. It is very rare that RMS originates from the temporal muscle. We report a case of adult SSRMS that originated from the temporal muscle, destroyed the skull, and invaded the dura mater. As far as we know, there have been no previous reports of a case like this one.

A 55-year-old male patient was admitted to our hospital with a lump in the left temporal region.

Two months prior to admission, the patient noticed a lump in his left temporal scalp. The patient had no headaches or nausea and vomiting. The patient came to the outpatient department. A computed tomography (CT) scan was done and surgery was recommended, but the patient refused. The tumor grew slowly.

The patient had a 2-year history of hypertension.

The patient had a 10-year history of smoking. He denied any family history.

Physical examination revealed a 6 cm × 7 cm hard, painless mass in the left temporal region. There was no redness or swelling on the surface of the mass.

Laboratory examination, including liver and renal functions, blood counts, electrolytes, and coagulation function were normal. Serum tumor markers, HIV antibody, tuberculosis, and syphilis were negative.

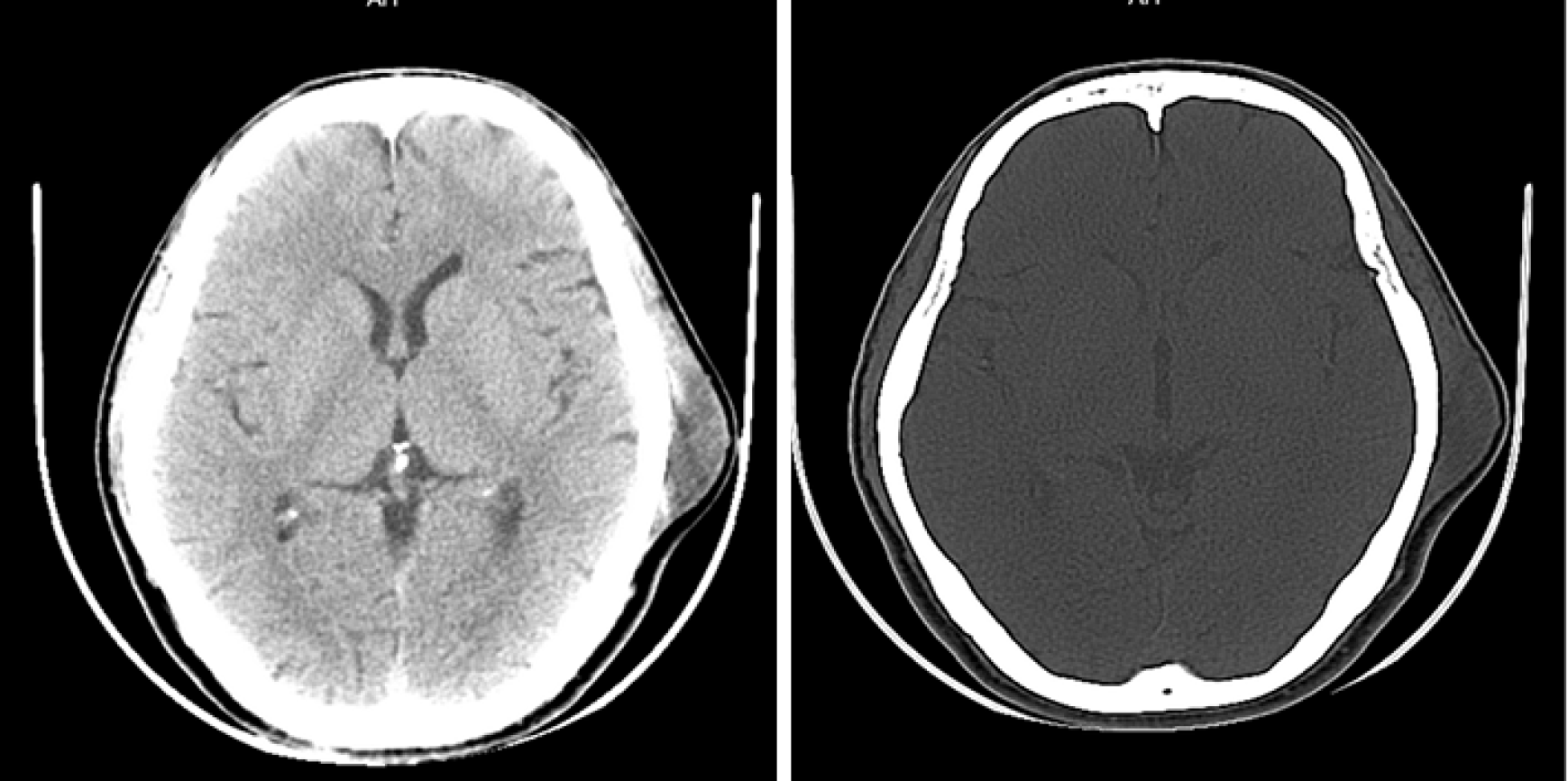

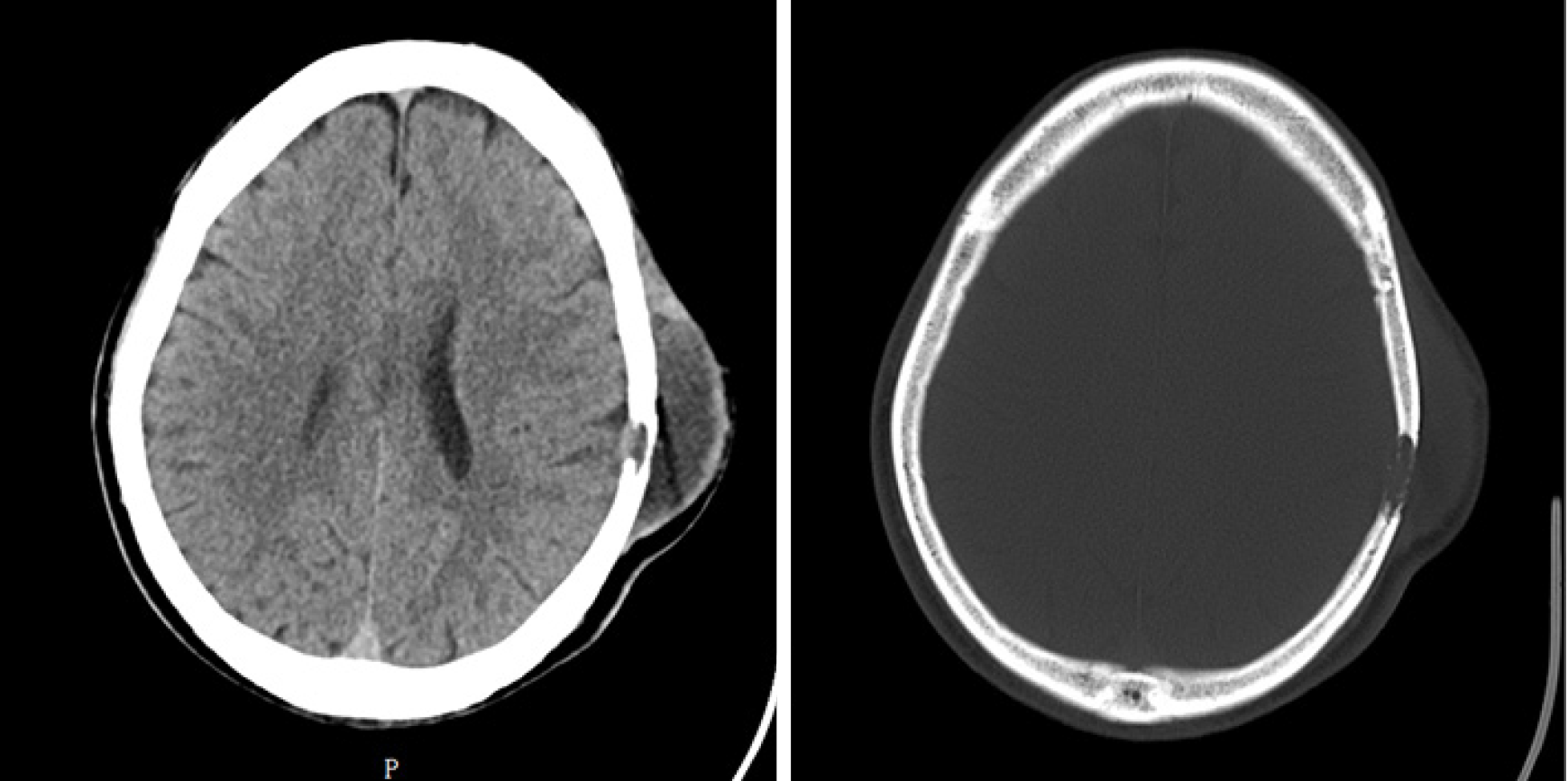

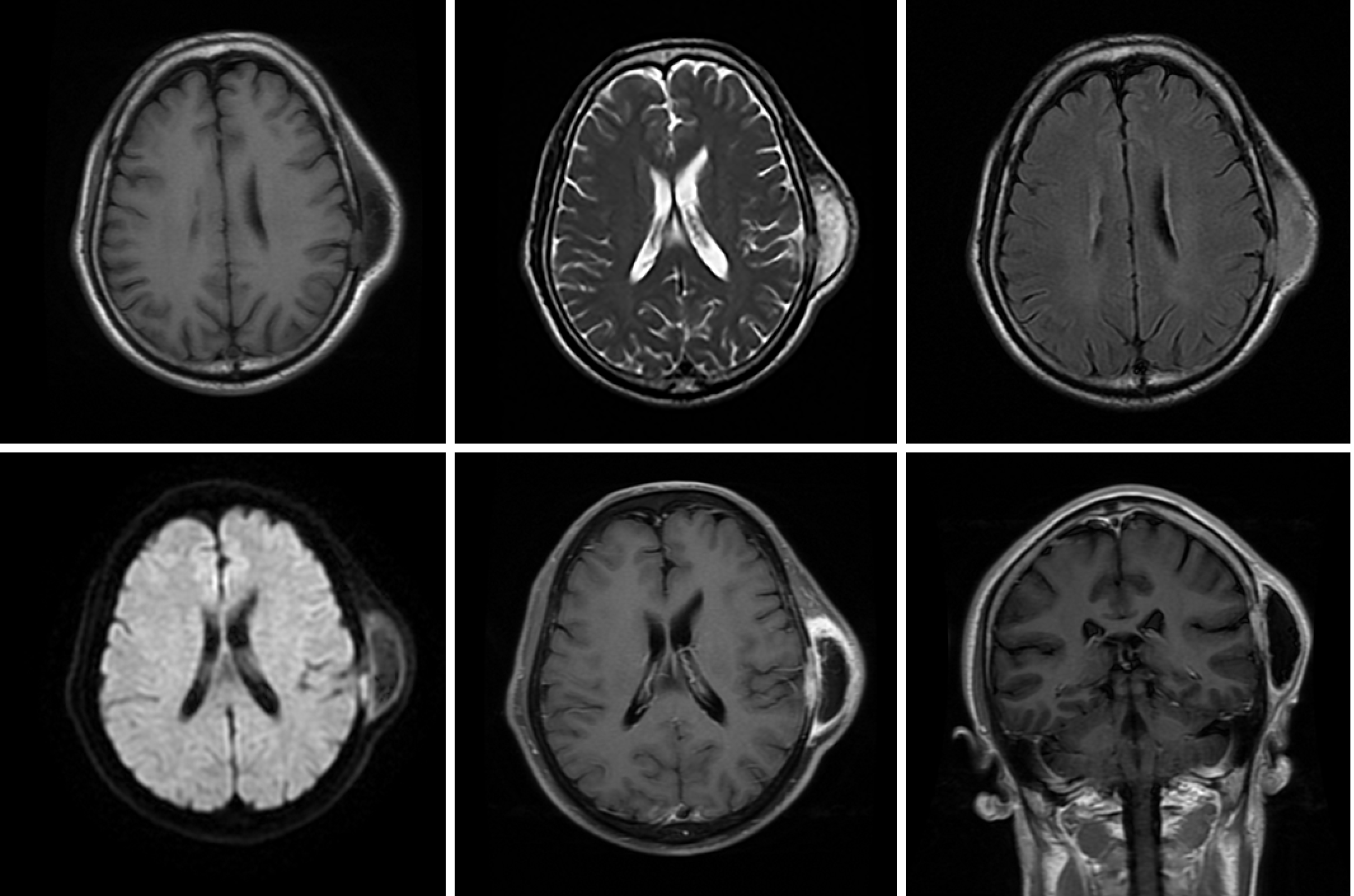

The first CT showed a subcutaneous mass in the left temporal region (Figure 1). The second CT revealed that the mass was enlarged and the adjacent skull was destroyed (Figure 2). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a mass in the left temporal muscle, with obvious enhancement around the tumor, but no enhancement in the center of the tumor (Figure 3).

The patient was admitted to our hospital with a diagnosis of left temporal soft tissue sarcoma, and metastatic tumor could not be ruled out. The pathology finding was SSRMS.

The tumor was resected. During the operation, it was found that the tumor originated from the temporal muscle and had destroyed the skull and invaded the meninges. The tumor was completely removed with negative margins, and part of the skull and meninges were removed. Pathological evaluation of intraoperative frozen sections revealed malignant tumors, so cranioplasty was not performed. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy were given after the operation. Eight cycles of vincristine, ifosfamide, and etoposide were planned. A total of 50.4 Gy of radiation was administered.

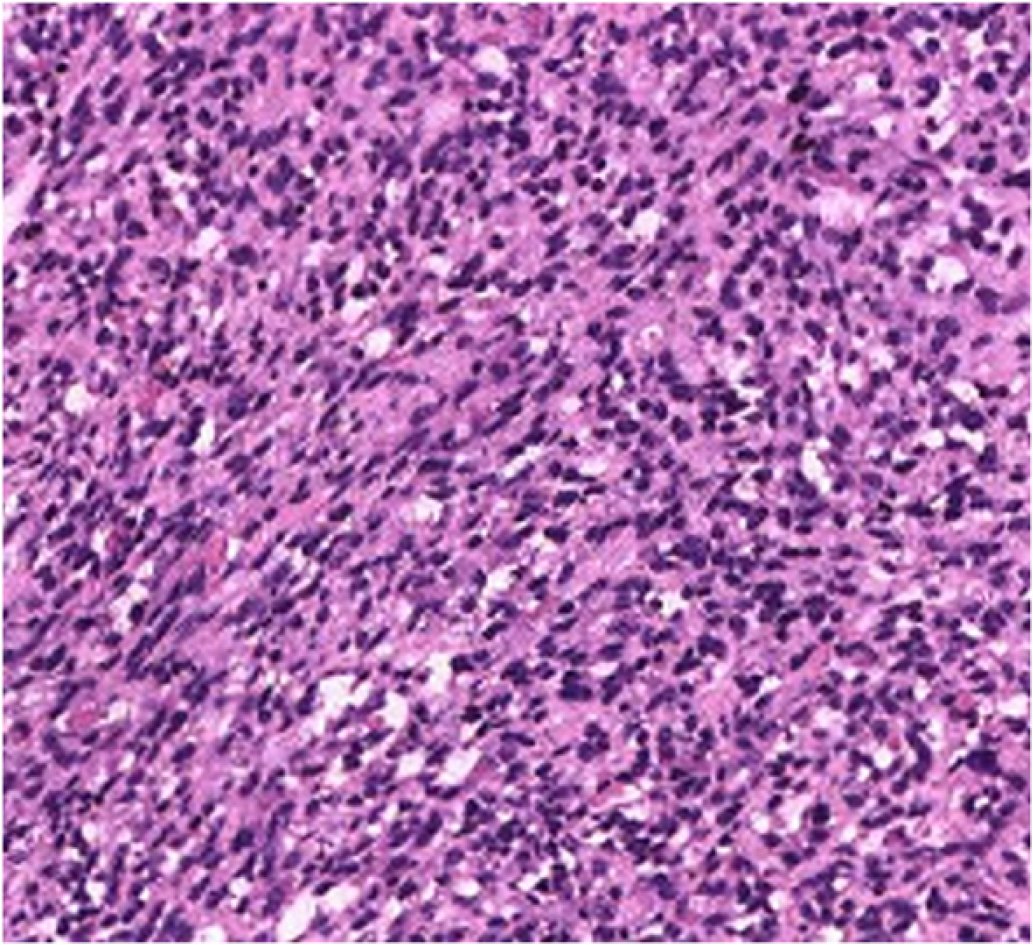

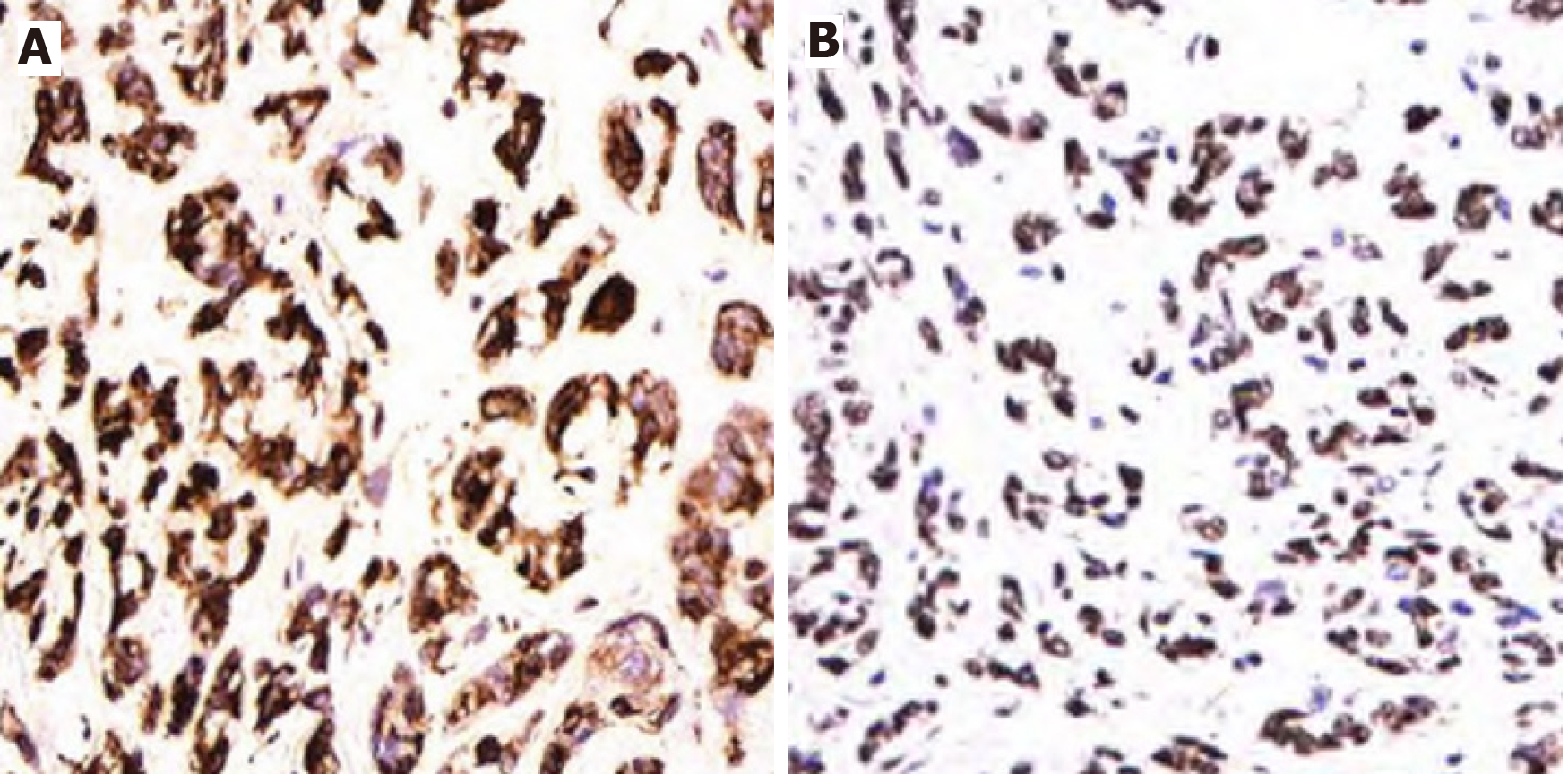

The postoperative recovery was good. Tumor recurrence was not seen at the 3 mo follow-up. Pathological examination revealed that the tumor was composed of mildly atypical spindle cells arranged in a crossed bundle or spiral. A few rhabdomyoblasts were scattered among the spindle cells (Figure 4). Immunohistochemistry showed desmin (+), MyoD1 (+), Ki-67 (+) 60%, CD10 (+), SMA (-), GFAP (-), myosin (-), S-100 (-), GFAP (-), TLE (-), and s (-) cells (Figure 5). The diagnosis was SSRMS.

Weber first reported RMS in 1854[3]. RMS is one of the most common tumors of children, about 250 new cases in children each year[1]. The age of onset has two peaks. The first is at 2 to 6 years of age and the second is at 14 to 18 years of age[2,4]. The median age is about 7 years[4]. Seventy percent of patients are younger than 10 years of age[5]. RMS has a very low incidence, and a high mortality rate, in adults[6].

RMS can originate from primitive mesenchymal cells anywhere in the body. Interestingly, most RMS tumors do not occur in muscles, but in areas where there is no muscle[2]. About 40% of RMSs occur in the head and neck region[2], followed by the urogenital tract, retroperitoneum, and limbs. The most common origins of head RMS are the orbits, nasopharynx, paranasal sinuses, middle ear, and external auditory canal[2,7]. The orbit is the most common single primary site[8]. This case originated from the temporal muscle, destroyed the skull, and invaded the meninges. Adult RMS is very rare in clinical practice. As far as we know, no similar case has been reported in the literature.

Traditionally, three main RMS subtypes, embryonic, alveolar, and polymorphic, are recognized. However, other variants have been described, including SSRMS[9]. SSRMS was added to the WHO disease classification in 2013. This case was diagnosed as SSRMS based on pathological findings and immunohistochemistry. RMS mostly manifests as a rapidly increasing mass that can invade nearby tissues and metastasize to distant sites. The main clinical features of this case of RMS were a fast-growing painless temporal muscle mass, destruction of the skull, invasion of meninges, and normal skin. The imaging findings of SSRMS have definitive characteristics. In this case, enhanced MRI showed obvious enhancement around the tumor, but the tumor center had an extremely low signal, and no enhancement, similar to the characteristics described by Freling et al[10].

RMS usually requires a variety of treatment modalities, depending on the tumor location, size, and metastasis[11]. It is usually recommended to completely remove the tumor if surgery will not cause significant loss of function[12]. Survival is better if a definite negative surgical margin is achieved[13], but in many cases, the tumor cannot be completely removed, and only biopsy is possible. The prognosis of RMS is related to age, site of origin, tumor size, and metastasis[14,15]. Chemotherapy can shrink tumors and reduce large tumors that cannot be completely resected to the extent that they are easier to remove[11]. RMS can easily metastasize to the bone marrow, and some small tumors that cannot be detected by imaging examinations may have spread to other parts of the body, which is why chemotherapy is needed[16]. Positive margins after MRS surgery will result in a higher local failure rate[17]. Radiotherapy can reduce the local failure rate after MRS surgery. Studies found that in patients receiving radiotherapy, there was no correlation between positive margins and local recurrence[17].

The prognosis of RMS is significantly improved by more aggressive comprehensive treatment. The 5-year disease-free survival rates of early and late localized tumors are 81%[18] and 41%[19] respectively. Maurer et al[20] reported that the 5-year survival rates were 92% for orbital tumors, 81% FOR non-parameningeal tumors, and 69% FOR parameningeal tumors. If RMS invades the meninges, brain, and cranial nerves, the prognosis is extremely poor, often with rapid recurrence after surgical resection[21] and a median survival of 5-9 mon[22]. Among the reported cases, there was no 5-year survival[23,24]. In this case, chemotherapy and radiotherapy were still given even though although the tumor was completely resected because the tumor had invaded the meninges. Some authors recommend radical resection supplemented with radiation and chemotherapy[25].

Adult SSRMS originating in the soft tissues of the scalp is very rare. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of SSRMS originating from the temporal muscle in an adult. It destroyed the skull and invaded the meninges. RMS is one of the differential diagnoses for head soft tissue tumors with short-term enlargement and skull infiltration. Preoperative CT or MRI is necessary for early detection of invasion of the skull and brain tissue.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gupta R S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Dasgupta R, Fuchs J, Rodeberg D. Rhabdomyosarcoma. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2016;25:276-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cunningham MJ, Myers EN, Bluestone CD. Malignant tumors of the head and neck in children: a twenty-year review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1987;13:279-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Weber CO. Anatomische Untersuchung einer hypertrophische Zunge nebst Besnerkungen uber die Neubildung quergestreifter Muskelfasern. Virchows Arch Pathol Anat. 1854;7:115-118. |

| 4. | Maurer HM, Beltangady M, Gehan EA, Crist W, Hammond D, Hays DM, Heyn R, Lawrence W, Newton W, Ortega J. The Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study-I. A final report. Cancer. 1988;61:209-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Maurer HM. Rhabdomyosarcoma in childhood and adolescence. Curr Probl Cancer. 1978;2:1-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Slemmons KK, Crose LE, Rudzinski E, Bentley RC, Linardic CM. Role of the YAP Oncoprotein in Priming Ras-Driven Rhabdomyosarcoma. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0140781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sohaib SA, Moseley I, Wright JE. Orbital rhabdomyosarcoma--the radiological characteristics. Clin Radiol. 1998;53:357-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wharam MD Jr, Foulkes MA, Lawrence W Jr, Lindberg RD, Maurer HM, Newton WA Jr, Ragab AH, Raney RB Jr, Tefft M. Soft tissue sarcoma of the head and neck in childhood: nonorbital and nonparameningeal sites. A report of the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study (IRS)-I. Cancer. 1984;53:1016-1019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mentzel T, Katenkamp D. Sclerosing, pseudovascular rhabdomyosarcoma in adults. Clinicopathological and immunohistochemical analysis of three cases. Virchows Arch. 2000;436:305-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Freling NJ, Merks JH, Saeed P, Balm AJ, Bras J, Pieters BR, Adam JA, van Rijn RR. Imaging findings in craniofacial childhood rhabdomyosarcoma. Pediatr Radiol. 2010;40:1723-38; quiz 1855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Green LB, Reese DA, Gidvani-Diaz V, Hivnor C. Scalp metastasis of paraspinal alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Cutis. 2011;87:186-188. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Puri PL, Sartorelli V, Yang XJ, Hamamori Y, Ogryzko VV, Howard BH, Kedes L, Wang JY, Graessmann A, Nakatani Y, Levrero M. Differential roles of p300 and PCAF acetyltransferases in muscle differentiation. Mol Cell. 1997;1:35-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 335] [Cited by in RCA: 344] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yeung P, Bridger A, Smee R, Baldwin M, Bridger GP. Malignancies of the external auditory canal and temporal bone: a review. ANZ J Surg. 2002;72:114-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Van Rijn RR, Wilde JC, Bras J, Oldenburger F, McHugh KM, Merks JH. Imaging findings in noncraniofacial childhood rhabdomyosarcoma. Pediatr Radiol. 2008;38:617-634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Skapek SX, Ferrari A, Gupta AA, Lupo PJ, Butler E, Shipley J, Barr FG, Hawkins DS. Rhabdomyosarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5:1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 475] [Cited by in RCA: 614] [Article Influence: 102.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Andrade CR, Trento GDS, Jeremias F, Giro EMA, Gabrielli MAC, Gabrielli MFR, Almeida OP, Pereira-Filho VA. Rabdomyosarcoma of the Mandible: An Uncommon Clinical Presentation. J Craniofac Surg. 2018;29:e221-e224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sharma N, George NA, Singh R, Iype EM, Varghese BT, Thomas S. Surgical Management of Head and Neck Soft Tissue Sarcoma: 11-Year Experience at a Tertiary Care Centre in South India. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2018;9:187-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Durve DV, Kanegaonkar RG, Albert D, Levitt G. Paediatric rhabdomyosarcoma of the ear and temporal bone. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2004;29:32-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Raney RB Jr, Lawrence W Jr, Maurer HM, Lindberg RD, Newton WA Jr, Ragab AH, Tefft M, Foulkes MA. Rhabdomyosarcoma of the ear in childhood. A report from the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study-I. Cancer. 1983;51:2356-2361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Maurer HM, Gehan EA, Beltangady M, Crist W, Dickman PS, Donaldson SS, Fryer C, Hammond D, Hays DM, Herrmann J. The Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study-II. Cancer. 1993;71:1904-1922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hayashi K, Ohtsuki Y, Ikehara I, Akagi T, Murakami M, Date I, Bukeo T, Yagyu Y. Primary rhabdomyosarcoma combined with chronic paragonimiasis in the cerebrum: a necropsy case and review of the literature. Acta Neuropathol. 1986;72:170-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Tefft M, Fernandez C, Donaldson M, Newton W, Moon TE. Incidence of meningeal involvement by rhabdomyosarcoma of the head and neck in children: a report of the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study (IRS). Cancer. 1978;42:253-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bradford R, Crockard HA, Isaacson PG. Primary rhabdomyosarcoma of the central nervous system: case report. Neurosurgery. 1985;17:101-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Taratuto AL, Molina HA, Diez B, Zúccaro G, Monges J. Primary rhabdomyosarcoma of brain and cerebellum. Report of four cases in infants: an immunohistochemical study. Acta Neuropathol. 1985;66:98-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Chen Q, Lu W, Li B. Primary sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma of the scalp and skull: report of a case and review of literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:2205-2207. [PubMed] |