Published online Jun 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i18.4734

Peer-review started: September 30, 2020

First decision: March 27, 2021

Revised: April 5, 2021

Accepted: April 20, 2021

Article in press: April 20, 2021

Published online: June 26, 2021

Processing time: 240 Days and 18 Hours

Meigs’ syndrome is regarded as a benign ovarian tumor accompanied by pleural effusion and ascites, both of which resolve after removal of the tumor. Patients often seek treatment in the Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine or other internal medicine departments due to symptoms caused by ascites or hydrothorax. Here, we report a rare case of Meigs' syndrome caused by granulosa cell tumor accompanied with intrathoracic lesions.

A 52-year-old women was admitted to the Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine due to coughing and expectoration accompanied with shortness of breath. Chest X-ray and chest computed tomography showed a modest volume of pleural fluid with pleural thickening in the right lung. The carbohydrate antigen 125 (CA125) concentration was 150.8 U/mL (normal, 0-35 U/mL) and no tumor cells were observed in pleural fluid. Nodules and a neoplasm with a fish meat-like appearance in the parietal pleura and nodules with a ‘string of beads’-like appearance in the diaphragm were found by thoracoscopic examination. Furthermore, pelvic magnetic resonance revealed a pelvic mass measuring about 11.6 cm × 10.0 cm × 12.4 cm with heterogeneous signal intensity and multiple hypointense separations. Total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral adnexectomy, and separation of pelvic adhesion were performed under general anesthesia. The pathology results showed granulosa cell tumor. At the 2-mo follow-up after the surgery, the hydrothorax subsided, and the CA125 level returned to normal.

For postmenopausal women with unexplained hydrothorax and elevated CA125, in addition to being suspected of having gynecological malignancy, Meigs’ syndrome should be considered.

Core Tip: A 52-year-old women was admitted to the Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine due to coughing and expectoration accompanied with shortness of breath. Chest X-ray and chest computed tomography showed pleural fluid in the right lung. The carbohydrate antigen 125 (CA125) concentration was elevated. This is the first case in which nodules and a neoplasm with a fish meat-like appearance in the parietal pleura and nodules with a ‘string of beads’-like appearance in the diaphragm were revealed by thoracoscopic examination. Pelvic magnetic resonance revealed a pelvic mass measuring about 11.6 cm × 10.0 cm × 12.4 cm and the pathology results showed granulosa cell tumor. After the surgery, the hydrothorax subsided, and the CA125 level returned to normal.

- Citation: Wu XJ, Xia HB, Jia BL, Yan GW, Luo W, Zhao Y, Luo XB. Meigs’ syndrome caused by granulosa cell tumor accompanied with intrathoracic lesions: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(18): 4734-4740

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i18/4734.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i18.4734

Meigs’ syndrome is a rare gynecological disease. Meigs[1] first reported this disease in 1939, and it initially referred to benign solid ovarian tumors accompanied by ascites and hydrothorax that gradually disappeared after surgical resection of ovarian lesion. It mainly occurs in patients with fibroids, fibroepithelial neoplasms, thecomas, granulosa cell tumors (GCTs), and sclerosing stromal tumors[2,3]. Subsequently, similar symptoms of ascites and hydrothorax were found to be associated with other benign pelvic lesions, such as benign teratoma, uterine leiomyomas, fallopian tube papilloma, and pelvic hemangioma, and these conditions are called pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome[4]. GCTs are sex cord stromal tumors with an incidence rate of (0.58-1.60)/1000000; they account for approximately 5% of all ovarian tumors[5]. GCT is a low-grade malignancy that can secrete estrogen. Ovarian masses in postmenopausal women with increased carbohydrate antigen 125 (CA125) are most often malignant, while Meigs’ syndrome is a benign disease.

GCT rarely causes Meigs’ syndrome. This article reports a case of Meigs’ syndrome with hydrothorax caused by GCT accompanied with intrathoracic lesions and combined with an increase in CA125, along with the diagnosis and treatment process.

A 52-year-old woman was admitted to the Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine due to "coughing and expectoration for 1 year and aggravation of these symptoms accompanied with shortness of breath for 1 mo".

One year before admission, the patient had little cough and sputum with no obvious cause, and occasionally dull pain under the xiphoid process, lasting about 10 s and relieving itself. She occasionally felt hot flashes and night sweats. One month before hospitalization, the patient was still coughing with white foamy sputum. The amount of sputum was small and it was not easy to cough up.

The patient had no specific past medical history.

There was no family history of the disease.

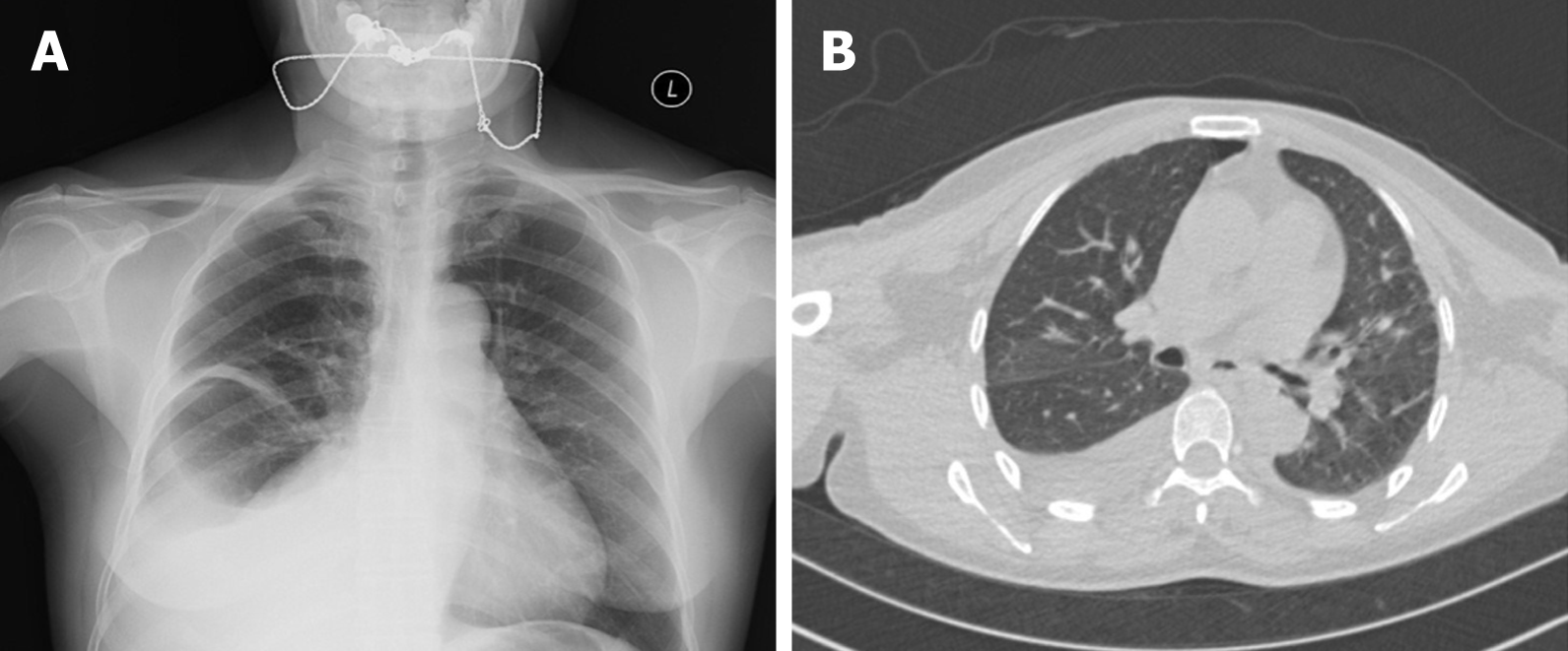

Percussion with auscultation was performed, with normal sounds in the left lung and dull sounds and decreased breath sounds in the right lower lung. The vaginal anterior wall had slight prolapse, the cervix was hypertrophic, and the mucous membrane was smooth. The uterine morphology and appendages were impalpable. There was a palpable pelvic mass with a size of approximately 10 cm × 12 cm, a hard texture, and an unclear border, but no tenderness. Chest X-ray and chest computed tomography showed a modest volume of pleural fluid with pleural thickening in the right lung (Figure 1).

The blood gas analysis indicated hypoxemia. The CA125 concentration was 150.8 U/mL (normal, 0-35 U/mL); the results of carcinoembryonic antigen, CA153, CA199, autoimmune antibody tests, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody tests were unremarkable. A drainage tube was placed in the right pleural cavity, and a total of 3760 mL of pleural fluid was withdrawn. Routine analysis of pleural fluid showed no clots in the bloody, slightly turbid pleural fluid, a white blood cell count of 630 × 106/L, a red blood cell (RBC) count of 66000 × 106/L, a percentage of monocytes of 90%, a percentage of multinucleate cells of 10%, and mucin (++). The biochemical analysis of the pleural fluid showed total proteins of 42.9 g/L, albumin of 31.6 g/L, lactate dehydrogenase of 97 U/L, and adenosine deaminase of 4.0 U/L.

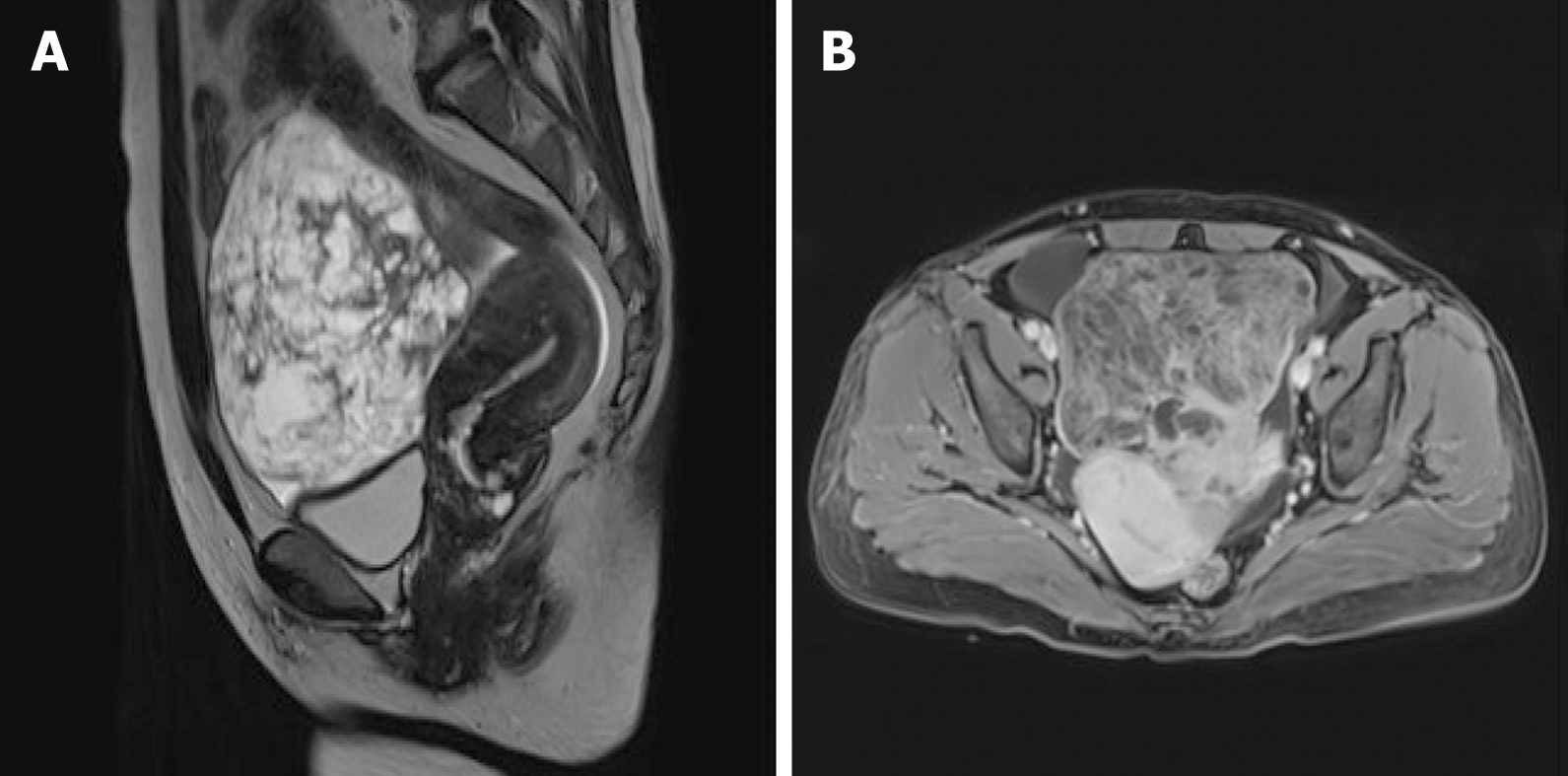

The thoracoscopic examination revealed nodules and a neoplasm with a fish meat-like appearance in the parietal pleura and nodules with a ‘string of beads’-like appearance in the diaphragm, accompanied by hyperemia and a brittle texture. The biopsy of the parietal pleura suggested chronic inflammation associated with hyperplasia of the mesothelial cells. Exfoliative cytology of tumor cells in pleural fluid showed that RBCs, lymphocytes, and mesothelial cells were observed in the pleural fluid, and no tumor cells were observed. Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a pelvic mass with heterogeneous signal intensity and multiple hypointense separations, a small amount of fat, characteristic signals of hemorrhage, and vessel signs (Figure 2). Therefore, mass effect, malignant tumor of ovarian origin, and pelvic effusion were considered.

The final diagnosis of the presented case was Meigs’ syndrome caused by GCT.

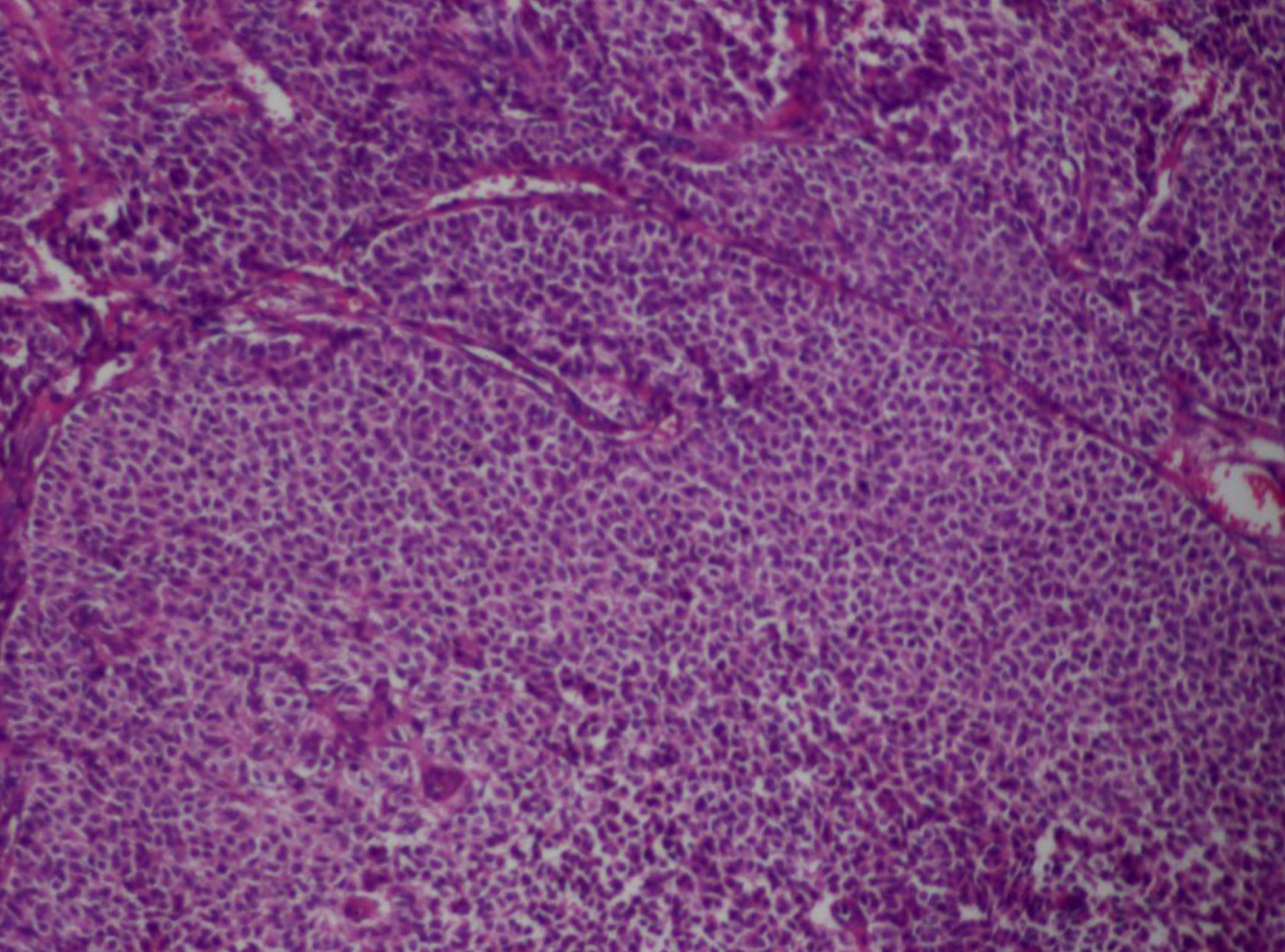

Total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral adnexectomy, separation of pelvic adhesion, and pelvic and abdominal drainage were performed under general anesthesia. Intraoperative findings included: The volume of bloody ascites was approximately 500 mL; the left ovary was enlarged to approximately 12 cm × 11 cm × 10 cm and had an irregular-shaped surface, an intact capsule, a brittle texture, proneness to bleeding, and adhesion to the left pelvic sidewall, and the appearances of the right uterine appendage and the left fallopian tube did not show obvious abnormalities; no palpable mass was found in the exploration of the intestine in the pelvic and peritoneal cavities, the greater omentum, and the liver. The left uterine appendage was removed, and pathology findings of frozen tissue sections suggested a suspected GCT (Figure 3). Postoperative immunohistochemistry assay showed that cluster of differentiation (CD), vimentin, and CD56 were all positive; calretinin and α-inhibin were focally positive; cytokeratin (CK), CK7, epithelial membrane antigen, chromogranin A, and synaptophysin were all negative; and the positive rate of Ki-67 was approximately 10%. Therefore, the patient was diagnosed with GCT (left uterine appendage).

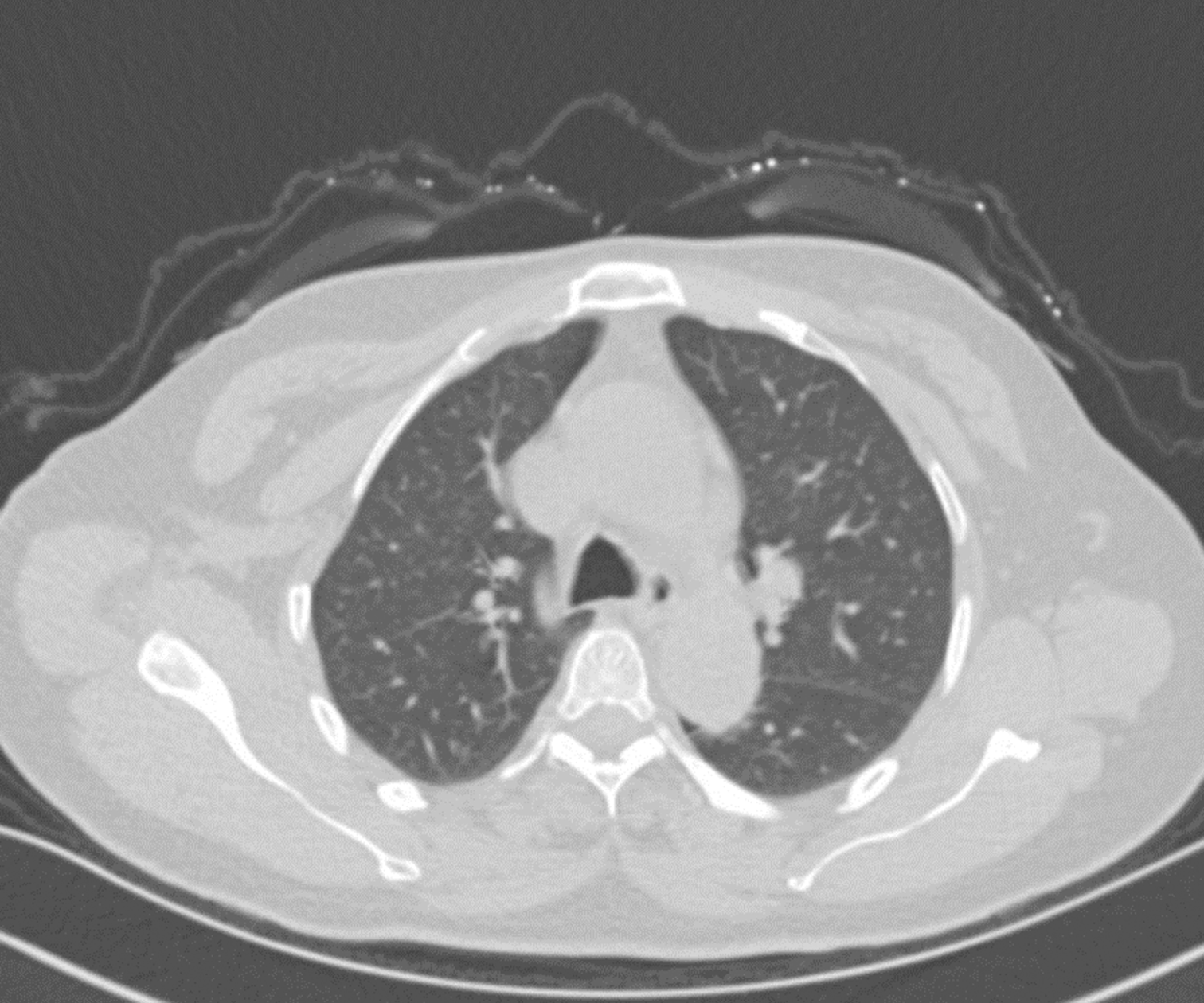

At the 2-mo follow-up after the surgery, the hydrothorax subsided (Figure 4), and the CA125 level returned to normal.

Meigs’ syndrome usually occurs in women aged 50 to 60 years. It rarely occurs in young women. Women under 30 years old diagnosed with Meigs’ syndrome account for less than 10% of all women diagnosed with this disease[6]. The diagnostic criteria for Meigs’ syndrome are as follows: The presence of ascites or hydrothorax associated with benign ovarian solid tumor(s) such as fibroids, thecomas, and GCTs and the disappearance of ascites and hydrothorax after removal of the tumor(s)[2]. Fibroids are the most common cause of Meigs’ syndrome. It has been reported that fibroids account for 2%-5% of surgically resected ovarian masses, and 1%-2% of fibroids meet the clinical diagnostic criteria for Meigs’ syndrome[7]. Meigs’ syndrome caused by GCTs is less common, and there were no reports that describe intrathoracic lesions. This is the first case in which nodules and a neoplasm with a fish meat-like appearance in the parietal pleura and nodules with a string of beads-like appearance in the diaphragm were revealed by thoracoscopic examination.

GCTs are classified as adult GCTs or juvenile GCTs, and 62% of adult GCT cases occur in postmenopausal women. Due to its endocrine characteristics, GCT mainly manifests as precocious puberty, irregular menstruation, vaginal bleeding, abdominal pain, and abdominal distension. However, the patient in this study did not have such symptoms.

The pleural fluid in patients with Meigs’ syndrome can be bloody or serous, with no tumor cells or microorganisms. The pleural fluid of the patient in this study had a bloody appearance. Pleural fluid and ascitic fluid are mostly exudates and in some cases, transudates, and their properties are generally consistent[8]. However, the mechanism underlying the occurrence of ascites and hydrothorax remains unclear. Meigs believed that ascites results from exudates from an edematous fibroid or from elevated pressure in pelvic and peritoneal lymphatic vessels caused by the tumor itself[9]. Second, in addition to the tumor surface, the peritoneum is the main factor that causes ascites[10]. It has recently been suggested that the pressure in lymphatic vessels in the tumor itself may cause fluid to escape through the superficial lymphatic vessels underneath the monolayer of epithelial cells covering the tumor into the peritoneal cavity to produce ascites[11]. The formation of hydrothorax may be also related to the ascitic fluid entering into the pleural cavity due to congenital absence of diaphragmatic lymphatic vessels or diaphragms[9]. Another study has shown that the formation of ascites and hydrothorax is associated with the increase in vascular permeability and capillary leakage caused by the release of inflammatory factors and growth factors[12]. Abramov et al[13] found high concentrations of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) in plasma, pleural fluid, and ascitic fluid samples from patients with Meigs’ syndrome and reported that after the removal of pelvic masses, the ascites and hydrothorax disappeared, and the plasma levels of VEGF, IL-6, and FGF also decreased. The VEGF level in ascitic fluid is higher than that in pleural fluid, indicating that the tumor(s) could lead to fluid exudation through the local release of growth factors. The disappearance of hydrothorax at the 2-mo follow-up after surgery was related to this tumor in our case.

Meigs’ syndrome with increased plasma CA125 is rare, and the mechanism of the increase in plasma CA125 is still unclear. A study has shown that CA125 in plasma originates from the interstitium rather than from fibrous tissue; therefore, it is speculated that elevated serum CA125 levels may be related to the secretion of CA125 by mesothelial cells[14,15]. Other reports have shown that elevated CA125 may be due to peritoneal irritation caused by increased intraperitoneal pressure and increased volumes of ascitic fluid[16,17]. The increase in CA125 was mostly related to ovarian malignancies, but pregnancy and some benign lesions, such as pelvic inflammation and endometriosis, could also lead to elevated CA125. In this case, the patient had significantly elevated CA125 accompanied by hydrothorax. Therefore, patients could be easily misdiagnosed with an ovarian malignancy with metastasis. However, the decreased CA125 after surgical resection of the tumor confirmed that the increase in CA125 was caused by GCT and it was a benign ovarian lesion.

Due to the low incidence of Meigs’ syndrome, it is often subject to misdiagnosis or delayed treatment. Patients often seek treatment in the emergency department or other internal medicine departments due to symptoms caused by ascites or hydrothorax. The patient in this case was first diagnosed in the Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. Although Meigs’ syndrome exhibits the clinical manifestations of malignant tumors, it is a benign disease, and surgery is the main treatment method. For young women, tumor removal or ipsilateral adnexectomy is recommended and for women who have given birth, hysterectomy plus bilateral adnexectomy is the main surgical procedure. The prognosis of this disease is usually good. After the resection of the tumor(s), the symptoms will gradually subside, and some patients even have no symptoms.

In conclusion, for postmenopausal women who have hydrothorax, if the characteristics of pleural fluid cannot be explained by common diseases such as tuberculous pleuritis, liver disease, kidney disease, or heart failure, it is necessary to complete tumor marker assays and gynecological color Doppler ultrasound and MRI examinations. If CA125 elevation also presents, in addition to being suspected of having gynecological malignancy, Meigs’ syndrome should be considered and the prognosis is usually satisfactory after resection of the ovarian lesions.

The authors would like to express gratitude to the doctors in Pathology Department and Imaging Department of the Suining Central Hospital for their assistance.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Soriano-Ursúa MA, Zheng KW S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Meigs JV. Fibroma of the ovary with ascites and hydrothorax: a further report. Ann Surg. 1939;110:731-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Meigs JV. Fibroma of the ovary with ascites and hydrothorax; Meigs' syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1954;67:962-985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Meigs JV. Pelvic tumors other than fibromas of the ovary with ascites and hydrothorax. Obstet Gynecol. 1954;3:471-486. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Nagakura S, Shirai Y, Hatakeyama K. Pseudo-Meigs' syndrome caused by secondary ovarian tumors from gastrointestinal cancer. A case report and review of the literature. Dig Surg. 2000;17:418-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ranganath R, Sridevi V, Shirley SS, Shantha V. Clinical and pathologic prognostic factors in adult granulosa cell tumors of the ovary. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18:929-933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Riker D, Goba D. Ovarian mass, pleural effusion, and ascites: revisiting Meigs syndrome. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2013;20:48-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nemeth AJ, Patel SK. Meigs syndrome revisited. J Thorac Imaging. 2003;18:100-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Krenke R, Maskey-Warzechowska M, Korczynski P, Zielinska-Krawczyk M, Klimiuk J, Chazan R, Light RW. Pleural Effusion in Meigs' Syndrome-Transudate or Exudate? Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e2114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | pages in obstetrics and gynecology. Joe Vincent Meigs and John W. Cass. Fibroma of the ovary with ascites and hydrothorax. With a report of seven cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1971;111:993. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Lin JY, Angel C, Sickel JZ. Meigs syndrome with elevated serum CA 125. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80:563-566. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Kortekaas KE, Pelikan HM. Hydrothorax, ascites and an abdominal mass: not always signs of a malignancy - Three cases of Meigs' syndrome. J Radiol Case Rep. 2018;12:17-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Saito F, Tashiro H, Honda R, Ohtake H, Katabuchi H. Twisted ovarian tumor causing progressive hemothorax: a case report of porous diaphragm syndrome. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2008;66:134-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Abramov Y, Anteby SO, Fasouliotis SJ, Barak V. Markedly elevated levels of vascular endothelial growth factor, fibroblast growth factor, and interleukin 6 in Meigs syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:354-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Liou JH, Su TC, Hsu JC. Meigs' syndrome with elevated serum cancer antigen 125 levels in a case of ovarian sclerosing stromal tumor. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;50:196-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Timmerman D, Moerman P, Vergote I. Meigs' syndrome with elevated serum CA 125 levels: two case reports and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 1995;59:405-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Macciò A, Madeddu C, Kotsonis P, Pietrangeli M, Paoletti AM. Large twisted ovarian fibroma associated with Meigs' syndrome, abdominal pain and severe anemia treated by laparoscopic surgery. BMC Surg. 2014;14:38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gerstenmaier JF, Gibson RN. Ultrasound in chronic liver disease. Insights Imaging. 2014;5:441-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |