Published online Jun 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i16.4110

Peer-review started: January 31, 2021

First decision: March 15, 2021

Revised: March 16, 2021

Accepted: March 24, 2021

Article in press: March 24, 2021

Published online: June 6, 2021

Processing time: 102 Days and 21.5 Hours

Atezolizumab is a programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitor, and its combi

A 75-year-old man was diagnosed with HCC recurrence after hepatectomy. He was administered immunotherapy with atezolizumab plus bevacizumab after an allergy to a programmed death-1 (PD-1) inhibitor. The patient showed a sudden onset of dizziness, numbness, and lack of consciousness with severe hypotension during atezolizumab infusion. The treatment was stopped immediately. The patient’s symptoms resolved after 5 mg dexamethasone was administered. Because of repeated hypersensitivity reactions to ICIs, treatment was changed to oral targeted regorafenib therapy.

Further research is necessary for elucidating the hypersensitivity mechanisms and establishing standardized skin test and desensitization protocols associated with PD-1 and PD-L1 to ensure effective treatment with ICIs.

Core Tip: Treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) can lead to hypersensitivity reactions; however, anaphylactic shock is rare. We present a case of life-threatening anaphylactic shock during atezolizumab infusion and performed a relevant literature review. Patients may be allergic to drugs targeting both programmed death-1 (PD-1) and programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1). Adequate attention should be paid to the related complications in the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Nevertheless, further studies are needed to understand the underlying mechanisms of hypersensitivity reactions and establish standardized skin test and desensitization protocols associated with PD-1 and PD-L1 to ensure effective treatment with ICIs.

- Citation: Bian LF, Zheng C, Shi XL. Atezolizumab-induced anaphylactic shock in a patient with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing immunotherapy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(16): 4110-4115

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i16/4110.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i16.4110

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a common carcinoma worldwide and a leading cause of cancer-related death[1]. Although early-stage disease may be curable by resection, most patients present with an advanced and unresectable disease[2]. The multikinase inhibitors sorafenib and lenvatinib are the approved first-line systemic treatments for unresectable HCC. Both are associated with considerable side effects that impair patients’ quality of life. Programmed death-1 (PD-1) inhibitors and anti–programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) have shown promising clinical activity as second-line treatments for HCC. A 2020 global phase 3 trial showed that in patients with unresectable HCC, atezolizumab combined with bevacizumab resulted in better overall and progression-free survival outcomes than sorafenib[3].

Although immune checkpoint inhibitors induce immune activation with strong antitumor effects, they can lead to hypersensitivity reactions (HSRs) and infusion reactions (IRs). These reactions range from mild cutaneous manifestations to life-threatening anaphylaxis with hypotension, oxygen desaturation, cardiovascular collapse, and death[4]. Atezolizumab is a humanized immunoglobulin (Ig)G-1 class antibody that binds to PD-L1 approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of cancer[5]. The FDA reported severe IRs in 1.3%-1.7% and HSRs in ≤ 1% of cases in which atezolizumab was used[6]. However, cases of atezolizumab-associated anaphylactic shock are rare. Herein, we present the case of a patient who developed life-threatening anaphylactic shock during atezolizumab infusion.

Fatigue, back pain, and loss of appetite for 1 mo.

A 75-year-old man with liver cancer recurrence after right radical hepatectomy in April 2019 was diagnosed with HCC. After a multidisciplinary discussion, the patient received a combination treatment of lenvatinib and a PD-1 inhibitor (camrelizumab, 200 mg/bottle; Heng Rui Pharmaceuticals Inc., China). Because the patient developed hypotension and rash on the second use of camrelizumab, it was discontinued. Moreover, the patient showed significant side effects of oral administration of lenvatinib, including diarrhea, fatigue, and loss of appetite, the drug was discontinued. In November 2020, the patient was hospitalized for immunotherapy. The regimen was changed to a PD-L1 inhibitor (atezolizumab, 1200 mg/bottle; Genentech, Inc., United States) combined with bevacizumab therapy. The first 1200 mg infusion was administered on November 10, 2020. Ten minutes into the atezolizumab infusion, the patient reported dyspnea, sudden dizziness, and numbness in his feet and was soon unconscious, with hypotension (56/38 mmHg), a heart rate of 85 bpm, temporal temperature of 36.7 °C, respiration rate of 25 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation of 92%.

The patient has a medical history of hypertension, diabetes, and coronary heart disease for many years, cerebral infarction for more than 4 years without obvious sequelae, and hepatitis B for more than 50 years, for which he was taking “entecavir”. He had an allergy history of PD-1.

There was no family history of malignant tumors.

Abdominal distension, back pain, concave edema of lower limbs, and no jaundice or palpable masses were observed.

Blood analysis revealed high levels of alpha-fetoprotein (66 ng/mL; normal, < 25 ng/mL), carcinoembryonic antigen (4.8 ng/mL; normal, < 5 ng/mL), and ferritin (355.7 ng/mL; normal, female < 150 U/mL, male < 200 U/mL). Routine blood test showed leukopenia (1.9 × 109/L; normal, 4-10 × 109/L) with predominant neutrophils (62.9%) with normal hematocrit and platelet count. Prothrombin and partial thromboplastin times were normal.

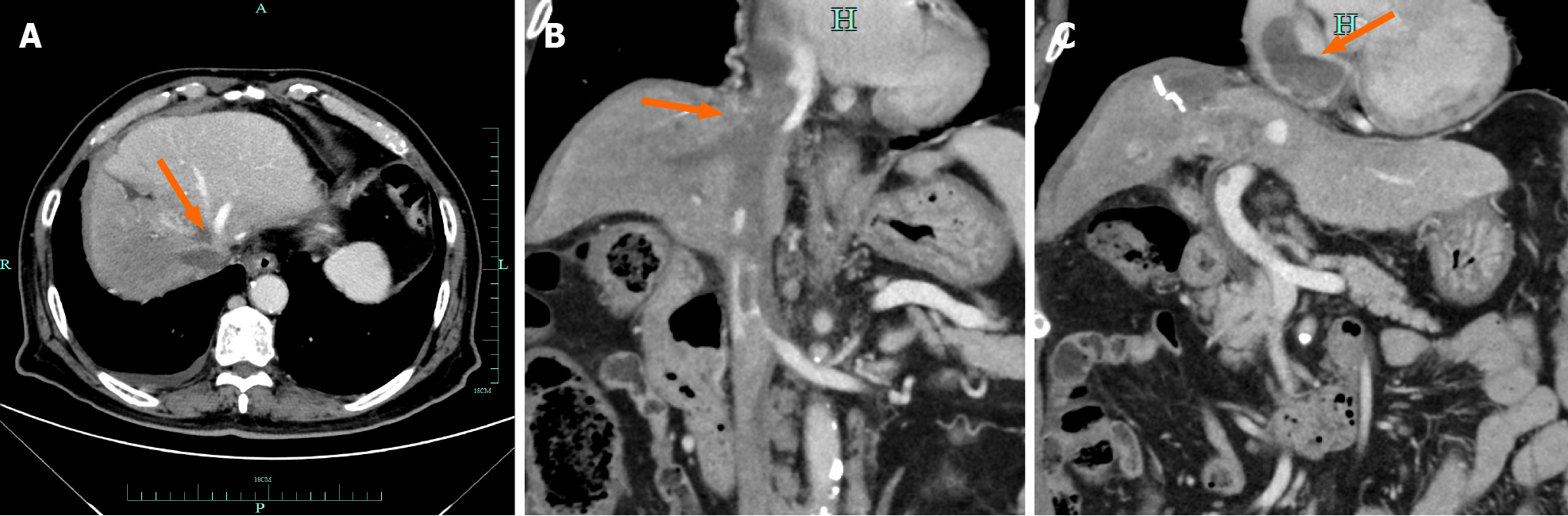

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of the chest and abdomen performed in September 2020 showed multiple intrahepatic tumors invading the inferior vena cava and right branch of the portal vein and tumor thrombus formation in the inferior vena cava and left atrium (Figure 1).

Hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence and atezolizumab-induced anaphylactic shock.

A nurse immediately stopped atezolizumab infusion, made the patient lie in the supine position, and reported to the physician. The patient was administered 5 mg dexamethasone intravenously, 500 mL of Ringers solution intravenous drip quickly, and oxygen at a flow rate of 3 L/min.

Ten minutes later, the patient regained consciousness. Thirty minutes later, the symptoms resolved: Blood pressure rose to 112/66 mmHg and heart rate to 75 bpm, the respiration rate was 20 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation was 95%. Because of repeated hypersensitivity reactions, the medical team decided that the patient would not be rechallenged with immunotherapy and administered oral targeted regorafenib therapy instead. After 1 d, the patient’s condition stabilized and he was discharged. The patient was in a stable condition 2 mo after discharge.

In recent years, immune checkpoint inhibitors have been widely used for patients with malignancies. Several cancer immunotherapies that target the PD-L1–PD-1 pathway is currently being evaluated in patients with HCC. The PD-1 drugs nivolumab, pembrolizumab, and camrelizumab are second-line drugs that have been approved by the FDA for the treatment of HCC. Atezolizumab selectively targets PD-L1 to prevent interaction with the receptors PD-1 and B7-1, thus reversing T-cell suppression[7]. Bevacizumab is a monoclonal antibody that targets vascular endothelial growth factor, inhibits angiogenesis and tumor growth, and showed response in patients with advanced liver cancer[8,9]. This patient, who had a recurrent tumor after liver cancer surgery, was advised to try immunotherapy with atezolizumab plus bevacizumab after an allergy to camrelizumab. Unfortunately, the patient had a severe allergic reaction at the first use of atezolizumab and immunotherapy was stopped after discussion between the medical group and the patient’s family. The patient then received lenvatinib targeted treatment instead.

According to the FDA 2016 label, severe IRs of atezolizumab were observed in 1.3%-1.7% of patients[10]. These reactions include the following symptoms: Back or neck pain, dizziness, chills, feeling like passing out, dyspnea or wheezing, fever, flushing, itching or rash, and swelling of face or lips. Moreover, immune-related adverse reactions (such as pneumonitis, colitis, hypophysitis, encephalitis, hepatitis, and pancreatitis) have been reported to affect various organs. In the European Medicines Agency 2019 assessment report, HSRs of atezolizumab were reported in in up to 10% of patients[11]. In addition, pruritis and rash were reported in more than 10% of patients[6]. According to the recent BC Cancer Agency Drug Manual, HSRs including anaphylaxis can be severe in < 1% of the patients, and immune-mediated rash may appear in 8%-18% (severe, 1%) of patients[10]. Prompt recognition and attention to immunotherapy infusion-related reactions could potentially prevent the fatal complications of anaphylaxis with immune checkpoint inhibitors.

HSRs are classified according to the time of onset as immediate (< 1 h of drug administration) or delayed (1 h to 1 wk after drug administration). Immediate-onset HSRs include IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reactions, acute infusion–related reactions, and cytokine release syndrome. However, these reactions may be clinically indistinguishable from each other, and patients may show mixed-type reaction

If the patient experiences suspected anaphylaxis to immune checkpoint inhibitors, a skin test with a nonirritating concentration of the culprit agent should be performed 4-6 wk after the reaction. A positive skin test strongly suggests an IgE-mediated mechanism. Timing is critical because mast cells are temporarily unresponsive to the allergen in skin tests for 4 wk. Although skin tests are the most specific and sensitive, there are no standardized protocols available for the definition of biological agents except omalizumab, adalimumab, infliximab, and etanercept[18]. Gonzalez-Diaz et al reported that they used concentrations of 60 mg/mL for atezolizumab and 25 mg/mL for bevacizumab in the skin prick test, and concentrations of 0.6 mg/mL and 0.25 mg/mL, respectively, in the intradermal skin tests[19]. Our patient did not undergo a skin test because of the severe allergic reaction.

If atezolizumab is the first-line treatment option or more effective than other drugs and the allergic reaction is not serious, desensitization can be performed under the supervision of an experienced allergist. A commonly used desensitization regimen for monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) is a 12-step/3 bag protocol previously for beta-lactam antibiotics[20]. Gonzalez-Diaz et al[19] reported that their 4-bag/16-step desensitization protocol for atezolizumab and bevacizumab was useful after severe anaphy

A case of anaphylactic shock associated with atezolizumab has been presented. With the evolution of cancer therapies, the likelihood of serious adverse events may increase. Patients may be allergic to drugs targeting both PD-1 and PD-L1. Adequate attention should be paid to the related complications in the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Nevertheless, further studies are needed to understand the underlying mechanisms of hypersensitivity reactions and establish standardized skin test and desensitization protocols to increase the safety and efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Giorgio A, Lee JJX S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Yuan YY

| 1. | Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53206] [Cited by in RCA: 55823] [Article Influence: 7974.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (132)] |

| 2. | Lau WY, Leung TW, Lai BS, Liew CT, Ho SK, Yu SC, Tang AM. Preoperative systemic chemoimmunotherapy and sequential resection for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2001;233:236-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, Kudo M, Breder V, Merle P, Kaseb AO, Li D, Verret W, Xu DZ, Hernandez S, Liu J, Huang C, Mulla S, Wang Y, Lim HY, Zhu AX, Cheng AL; IMbrave150 Investigators. Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1894-1905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2542] [Cited by in RCA: 4695] [Article Influence: 939.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 4. | Castells M. Drug Hypersensitivity and Anaphylaxis in Cancer and Chronic Inflammatory Diseases: The Role of Desensitizations. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Postow MA, Sidlow R, Hellmann MD. Immune-Related Adverse Events Associated with Immune Checkpoint Blockade. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:158-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2308] [Cited by in RCA: 3155] [Article Influence: 450.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gülsen A, Wedi B, Jappe U. Hypersensitivity reactions to biologics (part I): allergy as an important differential diagnosis in complex immune-derived adverse events. Allergo J Int. 2020;1-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Herbst RS, Soria JC, Kowanetz M, Fine GD, Hamid O, Gordon MS, Sosman JA, McDermott DF, Powderly JD, Gettinger SN, Kohrt HE, Horn L, Lawrence DP, Rost S, Leabman M, Xiao Y, Mokatrin A, Koeppen H, Hegde PS, Mellman I, Chen DS, Hodi FS. Predictive correlates of response to the anti-PD-L1 antibody MPDL3280A in cancer patients. Nature. 2014;515:563-567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3965] [Cited by in RCA: 4183] [Article Influence: 380.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chen DS, Hurwitz H. Combinations of Bevacizumab With Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancer J. 2018;24:193-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Finn RS, Zhu AX. Targeting angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma: focus on VEGF and bevacizumab. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2009;9:503-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | BC Cancer Agency. Cancer drug manual, drug name: atezolizumab. 2019. [cited 10 January 2021]. Available from: http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/drugdatabase-site/Drug%20Index/Atezolizumab_Monograph.pdf. |

| 11. | European Medicines Agency. Assessment report of atezolizumab (TECENTRIQ®). 2019. [cited 10 January 2021]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/tecentriq-epar-productinformation_en.pdf. |

| 12. | Bonamichi-Santos R, Castells M. Diagnoses and Management of Drug Hypersensitivity and Anaphylaxis in Cancer and Chronic Inflammatory Diseases: Reactions to Taxanes and Monoclonal Antibodies. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018;54:375-385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Akarsu A, Soyer O, Sekerel BE. Hypersensitivity Reactions to Biologicals: from Bench to Bedside. Curr Treat Options Allergy. 2020;7:71-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Soar J, Pumphrey R, Cant A, Clarke S, Corbett A, Dawson P, Ewan P, Foëx B, Gabbott D, Griffiths M, Hall J, Harper N, Jewkes F, Maconochie I, Mitchell S, Nasser S, Nolan J, Rylance G, Sheikh A, Unsworth DJ, Warrell D; Working Group of the Resuscitation Council (UK). Emergency treatment of anaphylactic reactions--guidelines for healthcare providers. Resuscitation. 2008;77:157-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Karmacharya P, Poudel DR, Pathak R, Donato AA, Ghimire S, Giri S, Aryal MR, Bingham CO 3rd. Rituximab-induced serum sickness: A systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015;45:334-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | O’Driscoll BR, Howard LS, Earis J, Mak V; British Thoracic Society Emergency Oxygen Guideline Group; BTS Emergency Oxygen Guideline Development Group. BTS guideline for oxygen use in adults in healthcare and emergency settings. Thorax. 2017;72:ii1-ii90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 306] [Cited by in RCA: 380] [Article Influence: 47.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chu DK, Kim LH, Young PJ, Zamiri N, Almenawer SA, Jaeschke R, Szczeklik W, Schünemann HJ, Neary JD, Alhazzani W. Mortality and morbidity in acutely ill adults treated with liberal vs conservative oxygen therapy (IOTA): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2018;391:1693-1705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 434] [Cited by in RCA: 519] [Article Influence: 74.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Brockow K, Garvey LH, Aberer W, Atanaskovic-Markovic M, Barbaud A, Bilo MB, Bircher A, Blanca M, Bonadonna B, Campi P, Castro E, Cernadas JR, Chiriac AM, Demoly P, Grosber M, Gooi J, Lombardo C, Mertes PM, Mosbech H, Nasser S, Pagani M, Ring J, Romano A, Scherer K, Schnyder B, Testi S, Torres M, Trautmann A, Terreehorst I; ENDA/EAACI Drug Allergy Interest Group. Skin test concentrations for systemically administered drugs -- an ENDA/EAACI Drug Allergy Interest Group position paper. Allergy. 2013;68:702-712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 548] [Cited by in RCA: 597] [Article Influence: 49.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Gonzalez-Diaz SN, Villarreal-Gonzalez RV, De Lira-Quezada CE, Rocha-Silva GK, Oyervides-Juarez VM, Vidal-Gutierrez O. Desensitization Protocol to Atezolizumab and Bevacizumab after Severe Anaphylaxis in the Treatment of Lung Adenocarcinoma. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2020;0. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Mirakian R, Leech SC, Krishna MT, Richter AG, Huber PA, Farooque S, Khan N, Pirmohamed M, Clark AT, Nasser SM; Standards of Care Committee of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology. Management of allergy to penicillins and other beta-lactams. Clin Exp Allergy. 2015;45:300-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |