Published online Jun 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i16.3988

Peer-review started: January 2, 2021

First decision: January 27, 2021

Revised: January 31, 2021

Accepted: March 9, 2021

Article in press: March 9, 2021

Published online: June 6, 2021

Processing time: 131 Days and 18.9 Hours

Colorectal mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma is a rare disease, and only a few cases have been reported to date. It has no specific clinical presentations and shows various endoscopic appearances. There is no uniform consensus on its treatment. With the advancement of endoscopic technology, endoscopic treatment has achieved better results in individual case reports of early-stage patients.

We report a case of rectal MALT in a 57-year-old Chinese man with no symptoms who received endoscopy as part of a routine physical examination, which incidentally found a 25 mm × 20 mm, laterally spreading tumor (LST)-like elevated lesion in the rectum. Therefore, he was referred to our hospital for further endoscopic treatment. Complete and curable removal of the tumor was performed by endoscopic submucosal dissection. We observed enlarged and dilated branch-like vessels similar to those of gastric MALT lymphoma on magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging. And immunopathological staining showed hyperplastic capillaries in the mucosa. Histopathological findings revealed diffusely hyperplastic lymphoid tissue in the lamina propria, with a visible lymphoid follicle structure surrounded by a large number of diffusely infiltrated lymphoid cells that had a relatively simple morphology and clear cytoplasm. In addition, immunohistochemical analysis suggested strongly positive expression for CD20 and Bcl-2. Gene rearrangement results showed positivity for IGH-A, IGH-C, IGK-B, and IGL. Taking all the above findings together, we arrived at a diagnosis of extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of MALT lymphoma. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography examination showed no other lesions involved. The patient will be followed by periodic endoscopic observation.

In conclusion, we report a case of rectal MALT with an LST-like appearance treated by endoscopic submucosal dissection. Further studies will be needed to explore the clinical behavior, endoscopic appearance, and treatment of rectal MALT.

Core Tip: Compared to mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) in the stomach, primary rectal MALT lymphoma remains a rare disease. There are no representative clinical symptoms or endoscopic features reported in the literature. We report a case of rectal MALT lymphoma with a laterally spreading tumor-like appearance. The lesion presented enlarged and dilated vessels on the surface. Endoscopic submucosal dissection was performed. The histopathological and immunohistochemical findings led to a diagnosis of rectal MALT lymphoma.

- Citation: Wei YL, Min CC, Ren LL, Xu S, Chen YQ, Zhang Q, Zhao WJ, Zhang CP, Yin XY. Laterally spreading tumor-like primary rectal mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(16): 3988-3995

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i16/3988.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i16.3988

Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma is a subtype of B cell lymphoma occurring in the extranodal lymphoid tissue marginal zone. It can involve various organs, including the gastrointestinal tract, salivary glands, thyroid, lung, and breast[1]. The stomach is one of the organs where MALT lymphoma most commonly occurs. Its development is thought to be closely associated with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection[2,3]. Unlike gastric MALT, the occurrence of colorectal MALT is extremely rare, and only a few cases have been reported to date. Its clinical presenta

Here, we present a case of rectal MALT treated by endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) and discuss the clinical behaviors, endoscopic features, and treatment outcomes of rectal MALT through a brief review of the literature.

A 57-year-old Chinese man presented to our hospital for further management of a laterally spreading tumor (LST)-like lesion in the proximal rectum accidently discovered on colonoscopy over 1 mo prior.

The biopsy results indicated an inflammatory hyperplastic polyp. The patient had no obvious symptoms and received screening endoscopy as part of a routine health examination. Gastroscopy showed chronic atrophic gastritis and inflammation of the cardia.

The patient had a history of diabetes mellitus for more than 6 mo and was administered metformin and other drugs to control his blood sugar. He also had a history of hypertension for more than 1 mo without medication.

He had a long smoking history of over 30 years, with an average of 20 cigarettes per day. He also had a drinking history for more than 30 years, with half a catty of liquor per day.

Physical examination upon admission showed that the patient was 1.82 m in height and 94 kg in weight. He had a blood pressure of 139/84 mmHg with a heart rate of 68 beat/min. He had clear lungs and normal heart sounds with no murmurs or gallops on auscultation. There were no obvious pathognomonic signs during physical examination of the abdomen.

No significant abnormal laboratory results were recorded in this patient.

Colonoscopy in our hospital also revealed a 25 mm × 20 mm, LST-like slightly elevated lesion in the proximal rectum with a red color (Figure 1A). To observe the microstructure and capillaries of the lesion, magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging (NBI) was carried out. It showed enlarged and dilated branch-like vessels on the surface of the tumor similar to those of gastric MALT lymphoma (Figure 1B). The margin of the lesion became clearer, and a type II pit pattern was observed on magnifying endoscopy after indigo carmine staining (Figure 1C and D). Gastroscopy revealed atrophic gastritis and cardia mucosa erosion with irregular microstructure and capillaries on magnifying endoscopy. The biopsy pathology indicated cardia inflammation with mild glandular atypia in the absence of H. pylori. Therefore, there were no endoscopic and pathological findings indicating gastric MALT lymphoma. Abdominal computed tomography showed no obvious abnormalities.

Based on endoscopic performance, histopathologic characteristics, and gene arrangement results, the patient was finally diagnosed with extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of MALT lymphoma.

To obtain the specimen for pathology and treat the lesion, the patient underwent curative ESD. On assessment of the ESD specimen, a slightly elevated, LST-like lesion measuring 25 mm × 20 mm was identified in the mucosal layer (Figure 1E).

Histopathological findings of the ESD specimen showed diffusely hyperplastic lymphoid tissue in the lamina propria with a lymphoid follicle structure surrounded by an abundance of diffusely infiltrated lymphoid cells. These lymphoid cells exhibited clear cytoplasm and similar sizes (Figure 2). The margins were negative.

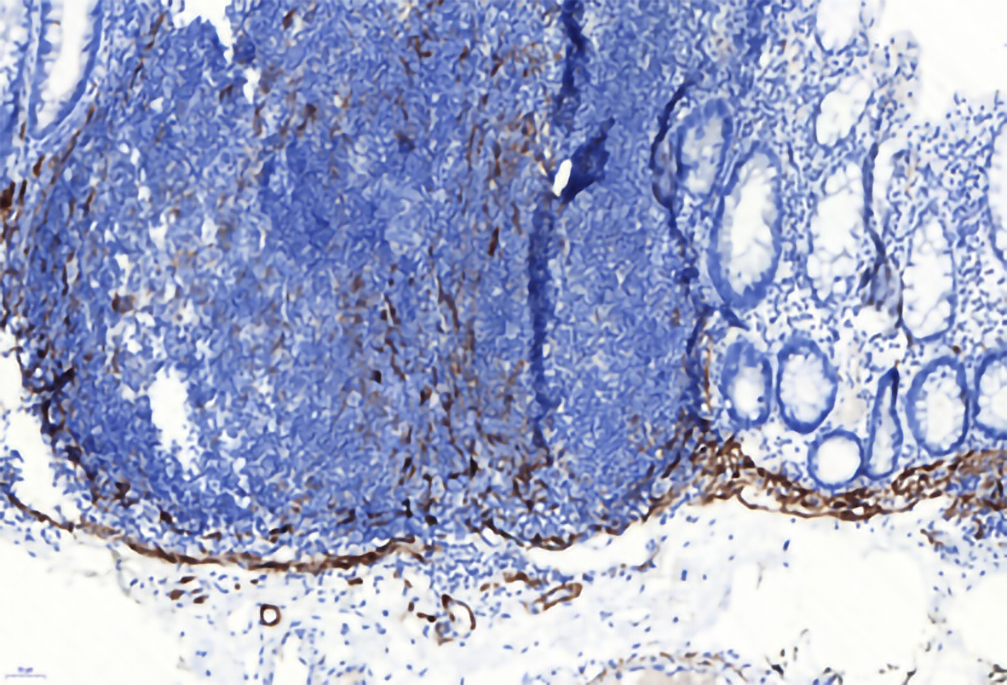

On immunohistochemical examination, BCL-2 and CD20 were strongly expressed in the tumor (Figure 3A and B), CD3 and CD21 were positive (Figure 3C and D), and CD10 and BCL-6 showed scattered positivity in the lesion (Figure 3E and F). CKpan was expressed in the residual epithelium, and CyclinD1 was negative in the tumor (Figure 3G and H). The Ki-67 labeling index was 20% (Figure 3I).

CD31 was used to mark the vascular endothelium in the mucosa, which showed hyperplastic capillaries but not obvious branch-like (Figure 4). Desmin labeling the muscularis mucosa indicated that the tumor was located in the mucosal layer and did not break through the muscularis mucosa. The tumor showed expansive growth, which made the muscularis mucosa obviously thinner (Figure 5).

Gene arrangement analysis showed that the specific IG genes in the original B lymphocytes were rearranged and displayed positive reactions for IGH-A, IGH-C, IGK-B, and IGL. IGH-B formed a typical monoclonal peak, but not in the positive range.

Complete and curable removal by ESD was performed. According to the suggestion of the hematology department, positron emission tomography-computed tomography was also performed, and no obvious tumor was found throughout the body. The patient required regular clinical and colonoscopic follow-up. The first endoscopy will be performed approximately 6 mo later, followed by a period of 6 mo to 1 year.

Primary gastrointestinal mucosa-associated non-Hodgkin lymphoma is most often located in the stomach, and the large intestine is rarely involved[4,5]. Primary colorectal lymphoma accounts for approximately 10% of all gastrointestinal lymphomas and 0.2% of colorectal malignancies[6,7]. Li et al[8] reported that abdominal pain was the most common symptom of primary colorectal lymphoma, and other symptoms, including diarrhea, blood stool, nausea, and changes in defecation habits, could also occur in primary colorectal lymphoma, according to their retrospective analysis of the clinical features of 40 cases of primary colorectal MALT lymphoma. Later, Jeon et al[9] reported that half of 51 cases were asymptomatic, and their lesions were discovered through screening colonoscopies in asymptomatic adults. Our patient also had no obvious symptoms, and the lesion was found only by routine endoscopy examination. Therefore, it is difficult to make a diagnosis through the clinical symptoms alone.

By reviewing the colonoscopy images of 51 patients, Jeon et al[9] divided the gross morphology of MALT lymphoma into polyposis, subepithelial tumor, epithelial mass, and ileitis type under white light endoscopy. However, there has been no further observation or study of the vessel and structure under image-enhanced colonoscopy. Tree-like-appearance blood vessels observed on magnified NBI have become the key to the diagnosis of gastric MALT lymphoma[10,11]. Unlike in the stomach, there are no qualitative endoscopic features to assist in the diagnosis of intestinal lymphoma. Hasegawa et al[12] reported a case of colon MALT lymphoma with magnified NBI in 2013 and found that the surface blood vessels showed dilated dendritic changes. In our case, LST was diagnosed under white light endoscopy. Magnifying endoscopy with narrowband imaging showed dilated branch-like vessels on the surface of the tumor, and a type II pit pattern was observed by indigo carmine staining. To further analyze the pathological characteristics of vessels, CD31 staining showed hyperplastic capillaries in the mucosa, but no obvious branch-like structures. Therefore, we suggest that dilated branch-like vessels may be a typical endoscopic feature of colorectal MALT, similar to gastric MALT. But it still needs more endoscopic and pathological studies to verify the meaning of the vessels.

The association of H. pylori and gastric MALT lymphoma is unquestioned, but the correlation with colorectal MALT lymphoma is uncertain. Matsuo et al[13] reported a case of H. pylori-positive colon MALT lymphoma but did not report H. pylori eradication treatment. Kelley[14] retrospectively analyzed 51 primary rectal lymphoma patients, only 12 of whom were H. pylori-positive, and did not confirm a relationship between this bacterium and the disease because there was no direct pathological evidence on rectal biopsy. Kikuchi et al[15] summarized the literature on antibiotic treatment in patients with H. pylori-negative primary colorectal lymphoma and found that it may be associated with other luminal microorganisms. Therefore, the relationship between primary colorectal MALT lymphoma and H. pylori or other microbes needs further investigation.

There is no uniform standard for the treatment of colorectal MALT lymphoma. According to the Lugano staging system, lymphoma confined to the gastrointestinal tract is stage I[16], which can have better outcomes from advanced endoscopic therapy[17]. Kajihara[18] reported that endoscopic mucosal resection was performed for primary rectal MALT lymphoma, with no sign of recurrence at the 5-year follow-up. Akasaka et al[19] reported on two colorectal lymphoma patients who underwent ESD treatment, and no clinical evidence of recurrence was found after regular examination. Besides, radiotherapy is also effective. Okamura et al[20] reported that three stage I cases achieved complete remission by radiotherapy. This clinical effect was also confirmed in case reports of Amouri et al[21], Foo et al[22], and Hayakawa et al[23]. The lesion in our case, limited to the rectum with no other tumor, was classified as stage I and was completely removed by ESD. The patient will be regularly monitored by clinical and colonoscopic follow-up.

In summary, primary rectal MALT lymphoma is a rare clinical entity. The clinical symptoms and endoscopic appearances are not specific, so more studies need to investigate them. With the continuous advancements in endoscopy, endoscopic treatment may become the priority for early-stage lesions.

We thank all the authors who contributed to this article.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A, A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Naem A, Strainiene S, Trifan A, Uesato M S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Zucca E, Conconi A, Pedrinis E, Cortelazzo S, Motta T, Gospodarowicz MK, Patterson BJ, Ferreri AJ, Ponzoni M, Devizzi L, Giardini R, Pinotti G, Capella C, Zinzani PL, Pileri S, López-Guillermo A, Campo E, Ambrosetti A, Baldini L, Cavalli F; International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group. Nongastric marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. Blood. 2003;101:2489-2495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 365] [Cited by in RCA: 355] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Parsonnet J, Hansen S, Rodriguez L, Gelb AB, Warnke RA, Jellum E, Orentreich N, Vogelman JH, Friedman GD. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1267-1271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1287] [Cited by in RCA: 1229] [Article Influence: 39.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wotherspoon AC, Ortiz-Hidalgo C, Falzon MR, Isaacson PG. Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis and primary B-cell gastric lymphoma. Lancet. 1991;338:1175-1176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1293] [Cited by in RCA: 1201] [Article Influence: 35.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zucca E, Roggero E, Bertoni F, Cavalli F. Primary extranodal non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Part 1: Gastrointestinal, cutaneous and genitourinary lymphomas. Ann Oncol. 1997;8:727-737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zinzani PL, Magagnoli M, Pagliani G, Bendandi M, Gherlinzoni F, Merla E, Salvucci M, Tura S. Primary intestinal lymphoma: clinical and therapeutic features of 32 patients. Haematologica. 1997;82:305-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kim YH, Lee JH, Yang SK, Kim TI, Kim JS, Kim HJ, Kim JI, Kim SW, Kim JO, Jung IK, Jung SA, Jung MK, Kim HS, Myung SJ, Kim WH, Rhee JC, Choi KY, Song IS, Hyun JH, Min YI. Primary colon lymphoma in Korea: a KASID (Korean Association for the Study of Intestinal Diseases) Study. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:2243-2247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Dionigi G, Annoni M, Rovera F, Boni L, Villa F, Castano P, Bianchi V, Dionigi R. Primary colorectal lymphomas: review of the literature. Surg Oncol. 2007;16 Suppl 1:S169-S171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Li B, Shi YK, He XH, Zou SM, Zhou SY, Dong M, Yang JL, Liu P, Xue LY. Primary non-Hodgkin lymphomas in the small and large intestine: clinicopathological characteristics and management of 40 patients. Int J Hematol. 2008;87:375-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Jeon MK, So H, Huh J, Hwang HS, Hwang SW, Park SH, Yang DH, Choi KD, Ye BD, Myung SJ, Yang SK, Byeon JS. Endoscopic features and clinical outcomes of colorectal mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87:529-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nonaka K, Nishimura M, Kita H. Role of narrow band imaging in endoscopic submucosal dissection. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;4:387-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nonaka K, Ohata K, Matsuhashi N, Shimizu M, Arai S, Hiejima Y, Kita H. Is narrow-band imaging useful for histological evaluation of gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma after treatment? Dig Endosc. 2014;26:358-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hasegawa D, Yoshida N, Ishii M, Takamasu M, Kishimoto M, Yagi N, Naitou Y, Yanagisawa A. [A case of colonic mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma observed under endoscopy with narrow-band imaging]. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2013;110:2100-2106. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Matsuo S, Mizuta Y, Hayashi T, Susumu S, Tsutsumi R, Azuma T, Yamaguchi S. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma of the transverse colon: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:5573-5576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kelley SR. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) variant of primary rectal lymphoma: a review of the English literature. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2017;32:295-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kikuchi Y, Matsui T, Hisabe T, Wada Y, Hoashi T, Tsuda S, Yao T, Iwashita A, Imamura K. Deep infiltrative low-grade MALT (mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue) colonic lymphomas that regressed as a result of antibiotic administration: endoscopic ultrasound evaluation. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:843-847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rohatiner A, d'Amore F, Coiffier B, Crowther D, Gospodarowicz M, Isaacson P, Lister TA, Norton A, Salem P, Shipp M. Report on a workshop convened to discuss the pathological and staging classifications of gastrointestinal tract lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 1994;5:397-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 363] [Cited by in RCA: 350] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Schwartz BL, Lowe RC. Successful Endoscopic Resection of Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue Lymphoma of the Colon. ACG Case Rep J. 2019;6:e00228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kajihara Y. Mucosa-associated lymphoid-tissue (MALT) lymphoma of the rectum. QJM. 2018;111:573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Akasaka R, Chiba T, Dutta AK, Toya Y, Mizutani T, Shozushima T, Abe K, Kamei M, Kasugai S, Shibata S, Abiko Y, Yokoyama N, Oana S, Hirota S, Endo M, Uesugi N, Sugai T, Suzuki K. Colonic mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2012;6:569-575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Okamura T, Suga T, Iwaya Y, Ito T, Yokosawa S, Arakura N, Ota H, Tanaka E. Helicobacter pylori-Negative Primary Rectal MALT Lymphoma: Complete Remission after Radiotherapy. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2012;6:319-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Amouri A, Chtourou L, Mnif L, Mdhaffar M, Abid M, Ayedi L, Daoud J, Elloumi M, Boudawara T, Tahri N. [MALT lymphoma of the rectum: a case report treated by radiotherapy]. Cancer Radiother. 2009;13:61-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Foo M, Chao MW, Gibbs P, Guiney M, Jacobs R. Successful treatment of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma of the rectum with radiation therapy: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1719-1723. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hayakawa T, Nonaka T, Mizoguchi N, Hagiwara Y, Shibata S, Sakai R, Nakayama N, Yokose T, Nakayama Y. Radiotherapy for mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma of the rectum: a case report. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2017;10:431-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |