Published online Jun 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i16.3919

Peer-review started: November 15, 2020

First decision: January 24, 2021

Revised: February 4, 2021

Accepted: March 10, 2021

Article in press: March 10, 2021

Published online: June 6, 2021

Processing time: 179 Days and 10.6 Hours

Open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) is the traditional surgical treatment for patellar fractures, and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA), especially Oxford UKA, has been increasingly used in patients with medial knee osteoarthritis (OA). However, the process of choosing treatment for patients with both patellar fractures and anteromedial knee OA remains unclear. We present the case of a patient with a patellar fracture and anteromedial OA.

We present the case of a 72-year-old woman with a history of bilateral medial compartment OA of the knees and a right Oxford UKA. She also experienced a recent left patellar fracture. ORIF and Oxford UKA were performed in a single stage. The patient showed excellent postoperative clinical results.

ORIF and Oxford UKA can be performed simultaneously for patients with patellar fracture and anteromedial OA on the same knee.

Core Tip: The routine treatment method for patellar fractures with knee osteoarthritis (OA) is staged surgery in which the patellar fracture is fixed first, then total knee arthroplasty or unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) is performed after the patellar fracture heals. We report a case of patellar fracture with anteromedial OA, we performed open reduction and internal fixation combined with Oxford UKA for this patient in a single stage, and she showed excellent postoperative clinical results. For elderly patients, single stage surgery reduces the risk of anesthesia and surgery, followed by less postoperative pain and cost.

- Citation: Nan SK, Li HF, Zhang D, Lin JN, Hou LS. Internal fixation and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty for an elderly patient with patellar fracture and anteromedial osteoarthritis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(16): 3919-3926

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i16/3919.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i16.3919

The patella is the largest sesamoid bone in the skeleton. It increases the lever arm of the extensor mechanism of the knee and reduces the amount of force needed to extend the knee. Patellar fractures are common, accounting for 1% of all skeletal injuries[1]. Patellar fractures can be treated conservatively or surgically[2]. Dislocations of more than 2 mm and comminuted fractures may cause articular incongruity and the presence of a nonfunctioning extensor mechanism and are considered strong indications for operative treatment[3]. In the presence of significant fracture displacement and articular incongruity, open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) is the standard of care to restore quadriceps function and prevent osteoarthritis (OA)[2]. Anatomical reduction, firm internal fixation, and early range of motion (ROM) exercises are basic principles in the treatment of patellar fractures.

OA is a common degenerative joint disease. The knee is the principal joint affected, resulting in progressive loss of function, pain, and stiffness. It is estimated that approximately a tenth of the population aged over 50 years will be affected[4]. OA affects the three compartments of the knee joint (medial, lateral, and patellofemoral joint) and usually develops slowly over 10–15 years, interfering with activities of daily living; at least 25% of patients with knee OA have isolated medial compartment disease[5]. Two treatment options for end-stage knee OA are unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) and total knee arthroplasty (TKA). UKA is associated with significantly lower postoperative morbidity and mortality than TKA[6]. UKA is widely used for unicompartmental knee OA. It includes fixed-bearing UKA and mobile-bearing UKA. The Oxford UKA is a type of mobile-bearing UKA and a successful treatment for end-stage, symptomatic anteromedial OA of the knee[7].

Surendran et al[8] reported the case of an elderly diabetic patient with knee OA who sustained a patellar fracture; the patient was treated by single-stage primary TKA and fixation of the patellar fracture. To the best of our knowledge, there are no reports on the use of UKA and ORIF as a treatment option for a patient with patellar fracture and knee OA. Here, we report a case of patellar fracture with anteromedial OA of the same side of the knee joint; we performed ORIF combined with Oxford UKA for this patient.

A 72-year-old woman presented with pain, swelling, and limited movement of her left knee 4 h after injury.

The patient had a 14-year history of osteoporosis and 10-year history of bilateral medial knee joint pain with limited movement due to anteromedial OA. On January 10, 2019, the patient underwent medial Oxford UKA of the right knee at our department. About 1 year after the operation, her pain in the right knee completely resolved, but pain in the left knee persisted and gradually increased. She was supposed to undergo left medial Oxford UKA at our department after January 2020. Owing to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, she could not come to the hospital. On the morning of February 9, 2020, she fell down and injured her left knee; she had severe pain in her knee and had limited movement. She was brought to our hospital. After X-ray examination, she was diagnosed with a comminuted fracture of the left patella. After COVID-19-related pneumonia was excluded, she was admitted to our department.

The patient had a history of hypertension with regular medication and no heart disease or diabetes.

The patient neither smoked nor drank and she denied any family history.

The results of the right knee surgery were excellent. Clinical examination of her left knee revealed local swelling without skin abrasion. There was obvious tenderness over the medial joint line and the surface of the patella, and the fracture space could be palpated. Passive ROM testing exacerbated the pain. The patient’s Oxford Knee Score before patellar fracture was 29 and body mass index was 20.5 kg/m2.

The laboratory test results were normal.

Radiographs showed a comminuted fracture of the left patella and confirmed OA of the medial knee compartment with osteophytosis and diffuse grade 4 cartilage defects. The lateral compartment was intact. The varus stress film of the left knee showed a “bone on bone” sign in the medial knee compartment (Figure 1).

The final diagnosis of the presented case was patellar fracture with anteromedial OA of the left knee joint.

The patient asked if we could perform patella fracture surgery and Oxford UKA in a single stage, owing to fear of pain from two operations. To answer her question, we conducted a relevant literature review and held case discussions. We then decided on a single-stage procedure with patellar fracture ORIF and Oxford UKA.

The operation was performed within 5 d following injury, under spinal anesthesia. The patient was in the supine position, and a tourniquet was placed on the proximal thigh. A longitudinal skin incision on the knee was made. After the skin incision, we found that the patellar fracture was comminuted, and the retinaculum on both sides was intact. The soft tissue around the medial patella was incised, the joint cavity was exposed, and the hematoma in the articular cavity was completely removed. We began to probe after the field was clear. The full layer cartilage of the medial condyle of the femur and the anteromedial full-thickness cartilage of the medial tibial plateau were worn. The anterior cruciate ligament was intact. The spaces between the lateral tibiofemoral joints were normal, and the cartilage on both sides was intact (Figure 2A).

A temporary fixation was performed with a reduction clamp. The main fragments were initially fixed by inserting two 2 mm parallel Kirschner wires. A 0.8 mm stainless steel wire was placed in a figure-of-eight fashion through the quadriceps and patellar tendon to obtain a modified anterior tension band. The second wire was stitched and wrapped in the same way as the first one. A peripatellar circumferential cerclage was then performed close to the bone (Figure 2B and C). In this step, we paid close attention to the position of wires, so that they did not produce friction with the Oxford UKA prosthesis, which could accelerate wear of prosthesis when the knee joint moves.

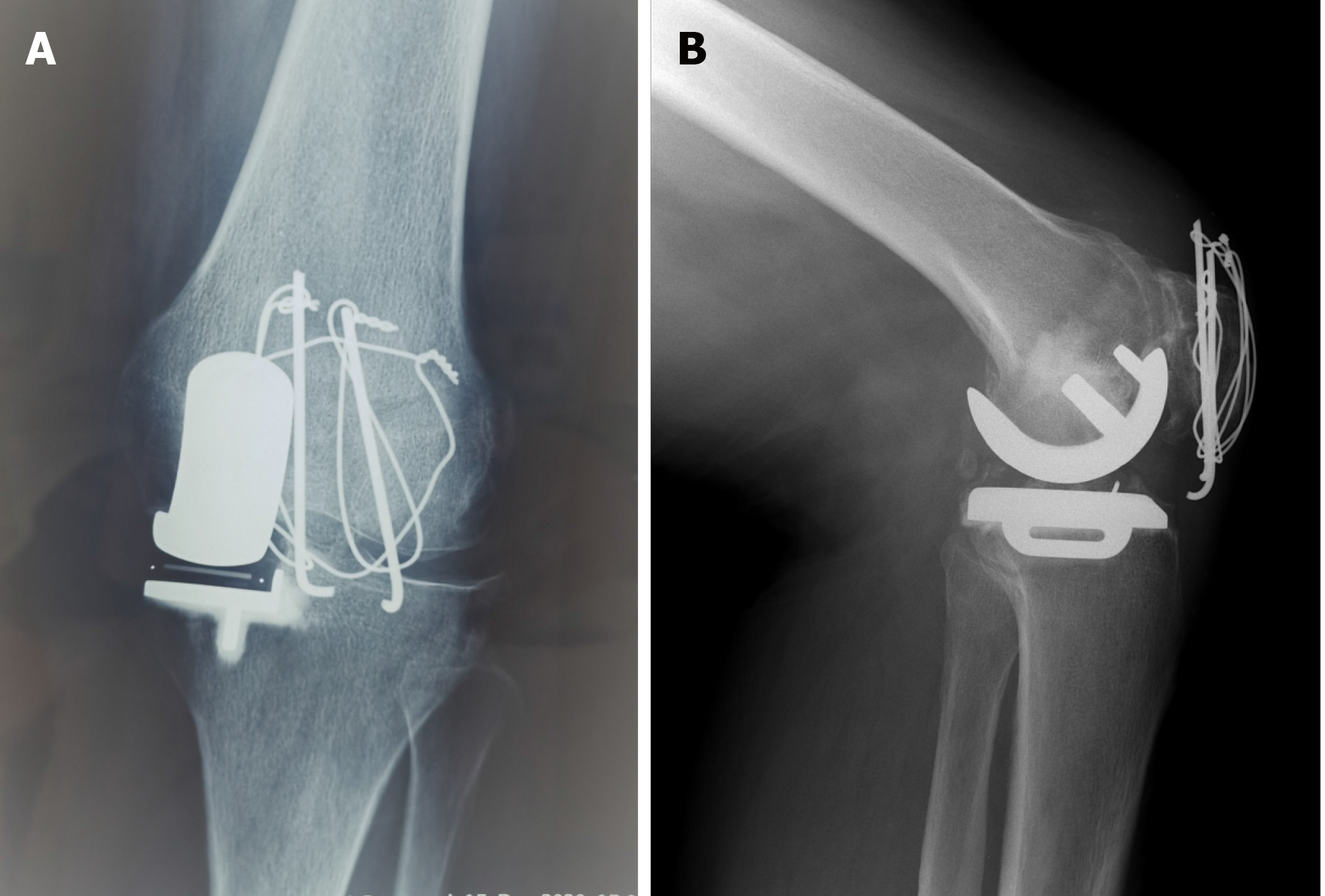

Next, we carefully checked the strength of the internal fixation and the stability of the knee joint in all directions. Then a classic medial Oxford UKA was performed (Figure 2B and C). Finally, the reduction and prosthesis were confirmed with a C-arm.

In the operating room, the left knee was immobilized with a hinged brace to keep it in a fully extended position to avoid excess stress on the patella.

The patient started continuous passive ROM training and was allowed to take full weight-bearing with crutches on the first day after surgery. Active ROM exercises were started on the second postoperative day. She had an ROM of 0–20° in the first week, following with 0–30° in the second week, and 0–45° in the third week. During which time she reported minor pain and was soon alleviated after physical therapy. At the 6th week of follow-up, her ROM was 0–90° without crutches. At the 12th week, the ROM was 0–110°. At 20 wk postoperatively, she showed good progress, with no pain during the examination and good mobility (ROM of 0–130°). The Oxford Knee Score was 11. Plain radiographs on the third day after surgery showed good reduction of the patellar fracture and an appropriate Oxford UKA (Figure 3). We could still see the fracture line on the follow-up X-ray film at the 8th week after operation, indicating that the fracture has not healed, but the fracture line had begun to blur (Figure 4). The X-ray film of 12th week follow-up showed that the fracture line had disappeared, indicating that the patella fracture has healed (Figure 5). At this time, the patient had basically returned to normal walking, although sometimes still needed a walker to walk. At the 20th week, her X-ray examination showed that the fracture has healed completely. Although the Kirschner wire was slightly displaced in the internal fixation, the internal fixation did not fail (Figure 6). The patient had regained the ability to walk normally, without the aid of a walker, and was completely satisfied with the effect of the operation.

To our knowledge, this is the first case of ORIF combined with Oxford UKA for the treatment of patellar fracture with anteromedial OA on the same side of the knee.

According to conventional knowledge, the routine treatment method for patellar fractures with medial knee OA is staged surgery in which the patellar fracture is fixed first and TKA or UKA is performed after the patellar fracture heals. Knee flexion and extension movements need to be restricted early after an operation for patellar fractures, especially for elderly osteoporotic patients, to avoid fracture displacement or the loosening of the internal fixation. However, continuous knee rehabilitation exercises are required early after TKA or UKA; these conditions are completely contradictory. Therefore, we only found one case of simultaneous patellar fracture fixation surgery and TKA[8].

As technology develops, UKAs, especially the Oxford UKA, have become successful treatment methods for symptomatic anteromedial OA. These prosthetics have been in use since the 1970s and yield excellent long-term survival and clinical outcomes[9]. UKA is less invasive and retains more of the patient’s knee joint structure than TKA. UKA procedures can obtain good knee ROM earlier and easier than TKA[10,11]. Therefore, patellar fractures should not be regarded as a contraindication to UKA. Further, UKA is associated with significantly lower postoperative morbidity and mortality[6].

Patellar fractures are contraindicated in TKA because these fractures reduce knee flexion and extension activities after surgery to avoid displacement of the fractured fragment and loosening of internal fixation. After UKA, performing functional exercises is easier; thus, patellar fractures are not deemed to be contraindicated in UKA. In addition, patients regain better ROM, return to activities quicker, have shorter hospital stays, gain superior function, and have a more natural feel of the knee after UKA[12]. The Oxford UKA is a type of mobile-bearing UKA and common for treating anteromedial OA of the knee[7].

We therefore believed that if anatomical reduction and firm internal fixation are achieved, the Oxford UKA might positively affect recovery and postoperative function due to reduced joint pain. Furthermore, the postoperative treatments in the prevention of thrombosis and pain control are consistent. For elderly patients, staged surgery involves a higher risk of anesthesia and surgery because of multiple separate surgical procedures, followed by more postoperative pain and greater cost. Therefore, we decided to perform patellar fracture internal fixation coupled with Oxford UKA in a single stage, and the patient agreed with our surgical plan.

To achieve firm fixation, various surgical methods have been introduced, such as stainless roll wire fixation, tension band wiring, percutaneous fixation, and arthroscopic fixation[13]. The modified tension band wiring, according to AO principles, is the most accepted and widely used technique for the treatment of displaced fractures of the patella. Lee et al[14] reported the use of modified tension band wiring using a FiberWire in 63 patients with comminuted patellar fractures. We believe that this method can be easier to handle and could reduce irritation or breakage of the wires compared to conventional methods. In addition, early rehabilitation can be allowed. Huang et al[15] reported the use of titanium cable cerclage in the management of patellar fractures in 24 patients. Functional exercises with active quadriceps exercises were started as early as the first day after surgery. The patients were followed for at least 12 mo. None of the patients presented with any postoperative complications. The management resulted in satisfactory outcomes. Titanium cable cerclage can offer a novel strategy in treating patellar fracture.

Our patient, an elderly woman with osteoporosis and a comminuted patellar fracture, accepted ORIF with a modified anterior tension band and peripatellar circumferential cerclage. This method can restore the joint surface and provide firm, stable fixation for early mobilization.

As for the surgical sequence, we chose to perform Oxford UKA after fracture reduction and internal fixation for several reasons. First, if the internal fixation of the patellar fracture is not rigid, we needed to abandon the Oxford UKA, because the patient would have then needed external fixation for the patella over a considerable time after surgery and the knee joint would not tolerate early functional exercise, which would have seriously affected the postoperative joint function of Oxford UKA. Second, if the Oxford UKA is performed without complete reconstruction of the knee extensor mechanism, the soft tissue tension of the knee joint could not be completely reconstructed, which may have affected meniscus bearing. In the internal fixation of the patellar fracture, we also paid attention to the position of the wires so that they did not produce friction with the prosthesis, which could have accelerated wear of the prosthesis when the knee joint moved.

The disadvantage of the single-stage patellar fixation with Oxford UKA is a contradiction between rehabilitation procedures, especially in the early postoperative period. For this patient, the ORIF operation resulted in anatomical reduction and firm internal fixation. Early joint movement was allowed, but she experienced more pain than normal for Oxford UKA patients during exercise; she took more time to obtain a good ROM.

Moreover, we presented only one case, and the follow-up period was rather short (20 wk). Long-term follow-up is needed to fully evaluate the impact of the operation. We aim at conducting further trials to compare 1-stage treatment with 2-stage treatment.

Patellar fracture may not be a contraindication for UKA in patients with isolated medial compartment OA. ORIF and UKA can be performed in single-stage operations for a patient with patellar fracture with anteromedial OA of the same side of the knee joint.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Feng M S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Heusinkveld MH, den Hamer A, Traa WA, Oomen PJ, Maffulli N. Treatment of transverse patellar fractures: a comparison between metallic and non-metallic implants. Br Med Bull. 2013;107:69-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kakazu R, Archdeacon MT. Surgical Management of Patellar Fractures. Orthop Clin North Am. 2016;47:77-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Carpenter JE, Kasman RA, Patel N, Lee ML, Goldstein SA. Biomechanical evaluation of current patella fracture fixation techniques. J Orthop Trauma. 1997;11:351-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lawrence RC, Helmick CG, Arnett FC, Deyo RA, Felson DT, Giannini EH, Heyse SP, Hirsch R, Hochberg MC, Hunder GG, Liang MH, Pillemer SR, Steen VD, Wolfe F. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected musculoskeletal disorders in the United States. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:778-799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Roos EM, Arden NK. Strategies for the prevention of knee osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12:92-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 337] [Article Influence: 33.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Liddle AD, Judge A, Pandit H, Murray DW. Adverse outcomes after total and unicompartmental knee replacement in 101,330 matched patients: a study of data from the National Joint Registry for England and Wales. Lancet. 2014;384:1437-1445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 408] [Cited by in RCA: 475] [Article Influence: 43.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Walker T, Hetto P, Bruckner T, Gotterbarm T, Merle C, Panzram B, Innmann MM, Moradi B. Minimally invasive Oxford unicompartmental knee arthroplasty ensures excellent functional outcome and high survivorship in the long term. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27:1658-1664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Surendran S, Pengatteeri YH, Park SE, Gopinathan P, Chang JD, Han CW. Osteoarthritis knee with patellar fracture in the elderly: single-stage fixation and total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22:1070-1073. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hooper N, Snell D, Hooper G, Maxwell R, Frampton C. The five-year radiological results of the uncemented Oxford medial compartment knee arthroplasty. Bone Joint J. 2015;97-B:1358-1363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hauer G, Sadoghi P, Bernhardt GA, Wolf M, Ruckenstuhl P, Fink A, Leithner A, Gruber G. Greater activity, better range of motion and higher quality of life following unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: a comparative case-control study. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2020;140:231-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Migliorini F, Tingart M, Niewiera M, Rath B, Eschweiler J. Unicompartmental vs total knee arthroplasty for knee osteoarthritis. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2019;29:947-955. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Brown NM, Sheth NP, Davis K, Berend ME, Lombardi AV, Berend KR, Della Valle CJ. Total knee arthroplasty has higher postoperative morbidity than unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: a multicenter analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27:86-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lefaivre KA, O'Brien PJ, Broekhuyse HM, Guy P, Blachut PA. Modified tension band technique for patella fractures. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2010;96:579-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lee BJ, Chon J, Yoon JY, Jung D. Modified Tension Band Wiring Using FiberWire for Patellar Fractures. Clin Orthop Surg. 2019;11:244-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Huang SL, Xue JL, Gao ZQ, Lan BS. Management of patellar fracture with titanium cable cerclage. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e8525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |