Published online May 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i15.3711

Peer-review started: December 28, 2020

First decision: January 24, 2021

Revised: February 1, 2021

Accepted: March 18, 2021

Article in press: March 18, 2021

Published online: May 26, 2021

Processing time: 135 Days and 4.6 Hours

Von Hippel-Lindau disease (also known as VHL syndrome), is an autosomal dominant inherited disease. We describe a sporadic case of VHL syndrome where bilateral pheochromocytomas were unexpectedly identified. The patient under

A 22-year-old man presented to our hospital to seek medical advice for infertility without any other complaints. The results of computed tomography and cate

This case summaries specific clinical traits and considerations in perioperative anesthesia management for VHL syndrome patients undergoing bilateral pheo

Core Tip: Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) syndrome is a rare autosomal dominant inherited disease, and anesthesia for patients with VHL syndrome undergoing bilateral pheo

- Citation: Wang L, Feng Y, Jiang LY. Anesthetic management of bilateral pheochromocytoma resection in Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(15): 3711-3715

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i15/3711.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i15.3711

Von Hippel-Lindau disease (also known as VHL syndrome), is an autosomal dominant inherited disease characterized by carcinomas in multiple organs with an incidence of approximately 1/36000. Its development is related to mutations in the VHL gene (a tumor suppressor gene, 3p25-26)[1]. Accompanying pheochromocytoma can be found in type 2 VHL but not in type 1, which is further classified into three subtypes (2A, 2B and 2C) depending on the risk of renal cell carcinoma or pheo

A 22-year-old male complained of infertility without any other discomfort.

The couple had been trying to conceive for 2 years.

The patient had an unremarkable medical history.

Personal and family history showed no specific illnesses.

The patients’s physical examination showed no abnormalities. His blood pressure (BP) and heart rate (HR) were 17.3/9.3 mmHg and 80 bpm, respectively.

The levels of catecholamines in blood (norepinephrine 283.1 pg/mL, epinephrine 47.5 pg/mL, dopamine /) and urine (norepinephrine 93 μg/24 h, epinephrine 3 μg/24 h, dopamine 137 μg/24 h) confirmed that the adrenal gland masses were pheochro

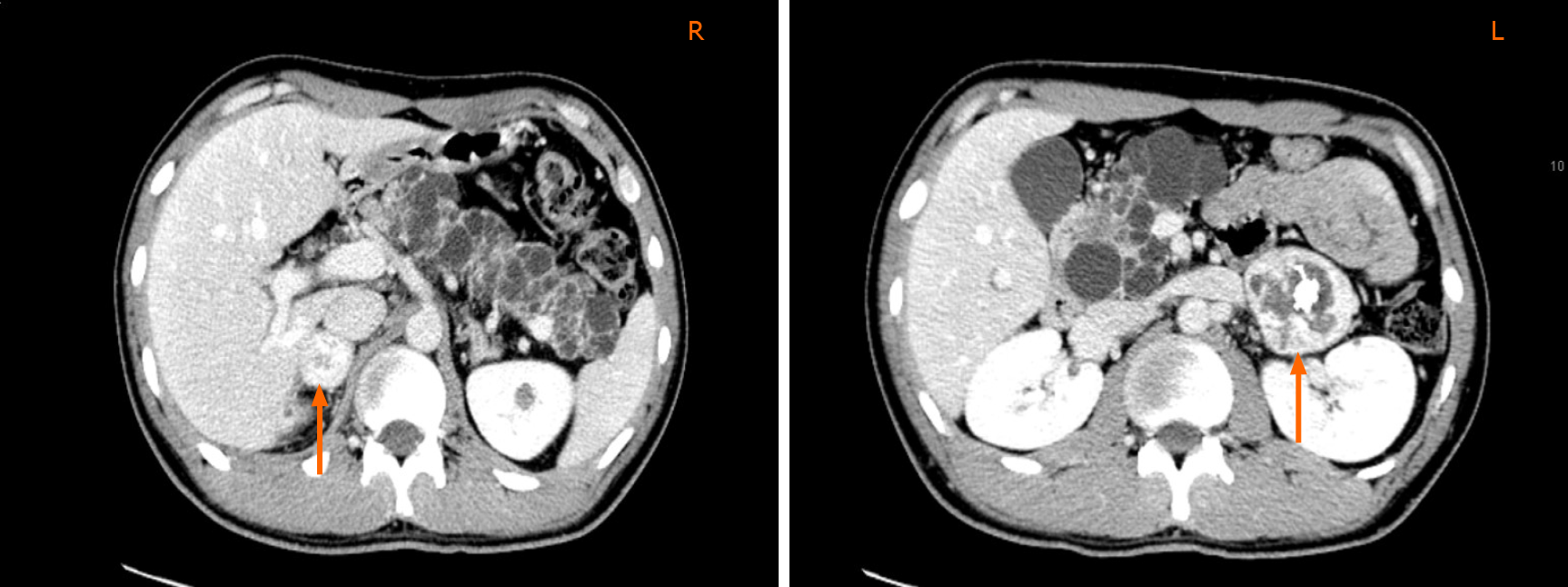

Computed tomography (CT) results indicated the association of multiple lesions: (1) Bilateral adrenal gland mass (Figure 1): The size of the left mass was 4.5 cm × 4.3 cm × 4.5 cm, and the right mass was 2.6 cm × 2.2 m × 3 cm; (2) Cysts in the upper region and a low-density occupying lesion on the left kidney; (3) Cystadenomas of the pancreas; and (4) Space occupying lesion with supply blood on the epididymis.

The patient was advised to undergo extensive imaging examinations. Multiple cystic nodules were detected in the thyroid by ultrasound. A single hemangioblastoma in the brainstem was characterized by magnetic resonance imaging, the diameter of which was approximately 5.6 mm along the medulla oblongata, which correlated with the clinical manifestations of Type 2B genotype-phenotype classification in families with VHL syndrome.

The patient was diagnosed with VHL syndrome.

It was decided that bilateral pheochromocytoma resections would be a reasonable treatment option. The pre-operative levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (431 U/L and 189 U/L, respectively) were significantly higher than normal due to massive replication of Hepatitis B Virus (HBV), which suggested poor liver function and did not meet the standards for surgery. Thus, the patient was transferred to the liver disease clinic. Two months later, he was transferred back to the urology ward for surgery following a reduction in ALT and AST (53 U/L and 27 U/L, respectively).

The patient was treated with terazosin 4 mg orally, together with hydroxyethyl starch 500 mL and crystal fluid 1000 mL intravenous infusion each day in preparation for the operation. A week later, he underwent right laparoscopic adrenalectomy. On arrival at the operating room the patient was monitored with electrocardiography, oxygen saturation (SpO2) by pulse oximetry, BP and a radial artery line for invasive arterial blood pressure (IBP). The initial IBP was 17.3/10. 7 kPa, HR was 90 bpm and SpO2 was 98%. Induction of anesthesia began after preparation of the peripheral vein, with midazolam 2 mg, propofol 160 mg, fentanyl 0.25 mg, cisatracurium 12 mg, and esmolol 80 mg intravenous, a tracheal cannula and right internal jugular vein catheter were placed sequentially. The central venous pressure was 0.5 kPa in the left lateral position before pneumoperitoneum was performed. Anesthesia was maintained by 1% sevoflurane, and intravenous infusion of propofol and remifentanil. Initial arterial blood gas analysis before surgery was normal. Following preparation and monitoring, we proceeded with the operation. During this process, when the surgeons peeled the tumor and managed its blood supply, as predicted the IBP fluctuated, with a peak of 25.7/12.3 kPa, and then dropped to 12.3/6.7 kPa as ligation of the veins started to drain the tumor. The BP was maintained by dopamine briefly for 20 min. Blood glucose varied from 111 mg/dL to 113 mg/dL during surgery, and fluid infusion of approximately 3600 mL was administered with an equal ratio of crystal and colloid. Hydrocortisone 100 mg was given to prevent an adrenalectomy-related cortisol crisis. After 3 h of surgery, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) and his BP was 17.2/10.1 kPa and HR was 93 bpm. Pathological diagnosis of the mass was a pheochromocytoma 3.5 cm × 2.5 cm × 2.0 cm in size.

His BP was maintained at 14.7/8.0 kPa after the first operation, routine blood cortisol test was 0.71 μg/dL at 8 AM, 0.65 μg/dL at 4 PM, and 0.47 μg/dL at midnight, Hydrocortisone was suggested at 100 mg during induction of anesthesia and 50 mg at the end of surgery to prevent a cortisol crisis during the second operation. Two weeks later, laparoscopic adrenalectomy on the left side was performed, using the same pro-operative preparation and monitoring methods. IBP did not increase but dropped dramatically from 16.0/10.0 kPa to 10.4/6.5 kPa, while HR rose markedly from 80 to 103 bpm during left adrenalectomy. His BP was maintained with vasopressors (dopamine 6 μg/kg/min, norepinephrine 0.06 μg/kg/min) until he was transferred to the ICU. Postoperative laboratory tests showed that blood norepinephrine concentration dropped from 283.1 pg/mL to 124.9 pg/mL, urine 24-h norepinephrine concentration dropped from 93 μg to 24 μg, and dopamine decreased from 137 μg to 77 μg. Pathological diagnosis of the mass confirmed a pheochromocytoma 6 cm × 4 cm × 3.5 cm in size.

The patient was discharged 10 d after surgery with BP at 16.0/10.7 kPa and hydrocortisone 50 mg as replacement therapy. Five years later, he returned with a growing epididymis mass. Pulmonary shadows on his X-ray findings accompanied by the history of hydrocortisone use after surgery suggested tuberculosis, which could not be excluded by CT. As a result, he was advised to undergo systematic treatment for tuberculosis and periodic review to evaluate the progression of VHL syndrome.

This patient initially only complained of infertility, but multiple tumors were found on routine examination. On reviewing his family history, it was discovered that his grandfather died from renal cell carcinoma in his 50’s, but his parents were alive and had not undergone medical examinations. Central nervous system and visceral lesions were detected including medullary hemangioblastoma, bilateral pheochromocytomas, left renal cyst, cystadenomas of the pancreas, space occupying lesion in the left kidney and in the epididymis, which proved the diagnosis of VHL syndrome.

For patients with VHL syndrome, anesthetic management during pheochro

There is a potential risk of medulla oblongata hemangioblastoma rupture in patients with VHL syndrome. Dramatic changes in BP during the operation can change intracranial and intraocular pressure with the risk of vitreous hemorrhage, retinal detachment and cerebral hernia; thus, early detection of intracranial hemorrhage is important[5]. The maintenance of blood and intracranial pressure is critical and requires careful consideration[6].

Thirdly, as morbidity and mortality of patients with VHL syndrome are linked to the progression of hemangioblastoma or renal cell carcinoma[7], if the patient’s liver function has been damaged due to HBV, the selection of drugs which do not damage renal and liver function is essential. For those with a family history of VHL syndrome, periodic surveillance to detect tumors early is essential[8]. Research has shown that pheochromocytoma can act as an indication of VHL syndrome, and bilateral pheochro

In summary, VHL syndrome is an autosomal dominant inherited disease, and due to its specific clinical traits perioperative management is more complex. We present a patient accidently diagnosed with VHL syndrome and the anesthesia management for bilateral pheochromocytoma resection is discussed. Learning about specific diseases and optimizing each treatment step is crucial for clinicians.

We would like to thank the patient for allowing us to share details of his diagnosis and treatment.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Anesthesiology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Zavras N S-Editor: Liu M L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Yuan YY

| 1. | Chou A, Toon C, Pickett J, Gill AJ. von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. Front Horm Res. 2013;41:30-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Shanbhogue KP, Hoch M, Fatterpaker G, Chandarana H. von Hippel-Lindau Disease: Review of Genetics and Imaging. Radiol Clin North Am. 2016;54:409-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lonser RR, Glenn GM, Walther M, Chew EY, Libutti SK, Linehan WM, Oldfield EH. von Hippel-Lindau disease. Lancet. 2003;361:2059-2067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1083] [Cited by in RCA: 1013] [Article Influence: 46.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lefebvre M, Foulkes WD. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma syndromes: genetics and management update. Curr Oncol. 2014;21:e8-e17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ercan M, Kahraman S, Başgül E, Aypar U. Anaesthetic management of a patient with von Hippel-Lindau disease: a combination of bilateral phaeochromocytoma and spinal cord haemangioblastoma. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 1996;13:81-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mugawar M, Rajender Y, Purohit AK, Sastry RA, Sundaram C, Rammurti S. Anesthetic management of von Hippel-Lindau Syndrome for excision of cerebellar hemangioblastoma and pheochromocytoma surgery. Anesth Analg. 1998;86:673-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Pilié PG, Jonasch E, McCutcheon IE. Key considerations in the treatment of von Hippel-Lindau disease. Future Oncol. 2016;12:1755-1758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rasmussen A, Alonso E, Ochoa A, De Biase I, Familiar I, Yescas P, Sosa AL, Rodríguez Y, Chávez M, López-López M, Bidichandani SI. Uptake of genetic testing and long-term tumor surveillance in von Hippel-Lindau disease. BMC Med Genet. 2010;11:4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Neumann HP, Berger DP, Sigmund G, Blum U, Schmidt D, Parmer RJ, Volk B, Kirste G. Pheochromocytomas, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2, and von Hippel-Lindau disease. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1531-1538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 306] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kittah NE, Gruber LM, Bancos I, Hamidi O, Tamhane S, Iñiguez-Ariza N, Babovic-Vuksanovic D, Thompson GB, Lteif A, Young WF, Erickson D. Bilateral pheochromocytoma: Clinical characteristics, treatment and longitudinal follow-up. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2020;93:288-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |