Published online May 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i15.3704

Peer-review started: January 7, 2021

First decision: January 24, 2021

Revised: January 25, 2021

Accepted: March 12, 2021

Article in press: March 12, 2021

Published online: May 26, 2021

Processing time: 123 Days and 21 Hours

Giant cell tumor of soft tissue (GCT-ST) is an extremely rare low-grade soft tissue tumor that is originates in superficial tissue and rarely spreads deeper. GCT-ST has unpredictable behavior. It is mainly benign, but may sometimes become aggressive and potentially increase in size within a short period of time.

A 17-year-old man was suspected of having a fracture, based on radiography following left shoulder trauma. One month later, the swelling of the left shoulder continued to increase and the pain was obvious. Computed tomography (CT) revealed a soft tissue mass with strip-like calcifications in the left shoulder. The mass invaded the adjacent humerus and showed an insect-like area of destruction at the edge of the cortical bone of the upper humerus. The marrow cavity of the upper humerus was enlarged, and a soft tissue density was seen in the medullary cavity. Thoracic CT revealed multiple small nodules beneath the pleura of both lungs. A bone scan demonstrated increased activity in the left shoulder joint and proximal humerus. The mass showed mixed moderate hypointensity and hyperintensity on T1-weighted images, and mixed hyperintensity on T2-weighted fat-saturated images. The final diagnosis of GCT-ST was confirmed by pathology.

GCT-STs should be considered in the differential diagnosis of soft tissue tumors and monitored for large increases in size.

Core Tip: Giant cell tumor of soft tissue (GCT-ST) is a rare primary soft tissue tumor that sometimes leads to local recurrence, but rarely to distant metastasis. In this case, the tumor exhibited strip-like calcifications, and the mass destroyed the cortical bone and invaded the bone marrow cavity. Magnetic resonance imaging was performed to establish the extent of the mass. We found multiple small nodules beneath the pleura of both lungs, which we considered as metastases. Development of an aggressive GCT-ST after adolescent trauma is rare. GCT-ST should be considered when interpreting limb masses that involve calcification and bone destruction.

- Citation: Huang WP, Zhu LN, Li R, Li LM, Gao JB. Malignant giant cell tumor in the left upper arm soft tissue of an adolescent: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(15): 3704-3710

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i15/3704.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i15.3704

Giant cell tumor of soft tissue (GCT-ST) is a rare primary soft tissue tumor; most originate from the subcutaneous superficial soft tissue of the extremities. The clinical manifestations are not specific, most are asymptomatic masses, and they rarely invade the deeper tissue[1,2]. Histologically and immunohistochemically, GCT-STs are similar to giant cell tumors (GCTs) of bone, and GCT-STs are thought to be their counter

A 17-year-old man with a 1-mo history of left shoulder trauma was admitted to our hospital.

One month prior to admission, the patient’s left shoulder accidentally touched a staircase handrail and he experienced mild pain. Abduction of the left upper limb was slightly limited and there was no swelling. Radiographic examination of the left shoulder joint at the local hospital, showed no obvious bone and joint lesions and no treatment was carried out. Persistent swelling and pain in the left shoulder continued after 15 d of treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; the pain was not relieved and gradually worsened.

The patient was in good health prior to the present illness.

The patient had no previous or family history of similar illnesses.

Physical examination revealed a left shoulder joint in forced adduction. The lateral and anterior sides of the left shoulder were obviously swollen, tender, with no pulsation, and the local skin temperature was increased. The patient was conscious of spon

A complete blood count revealed that the patient’s serum C-reactive protein level (70.92 mg/L, normal range 0-5 mg/L), lactate dehydrogenase (751 U/L, normal range 313-618 U/L), fibrinogen (6.29 g/L, normal range 2-4 g/L), D-dimer (5.997 mg/L, normal range 0-0.3 mg/L), alkaline phosphatase (453 U/L, normal range 35-105 U/L), and ferritin (790.80 μg/L, normal range 15-200 μg/L) were increased. Tumor-marker assays revealed that neuron-specific enolase was increased to 41.43 ng/L (normal range 0-25 ng/L).

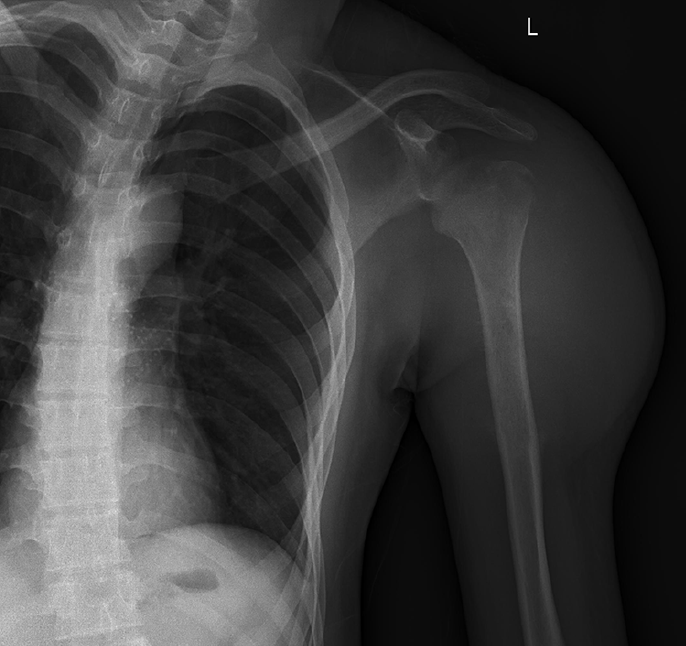

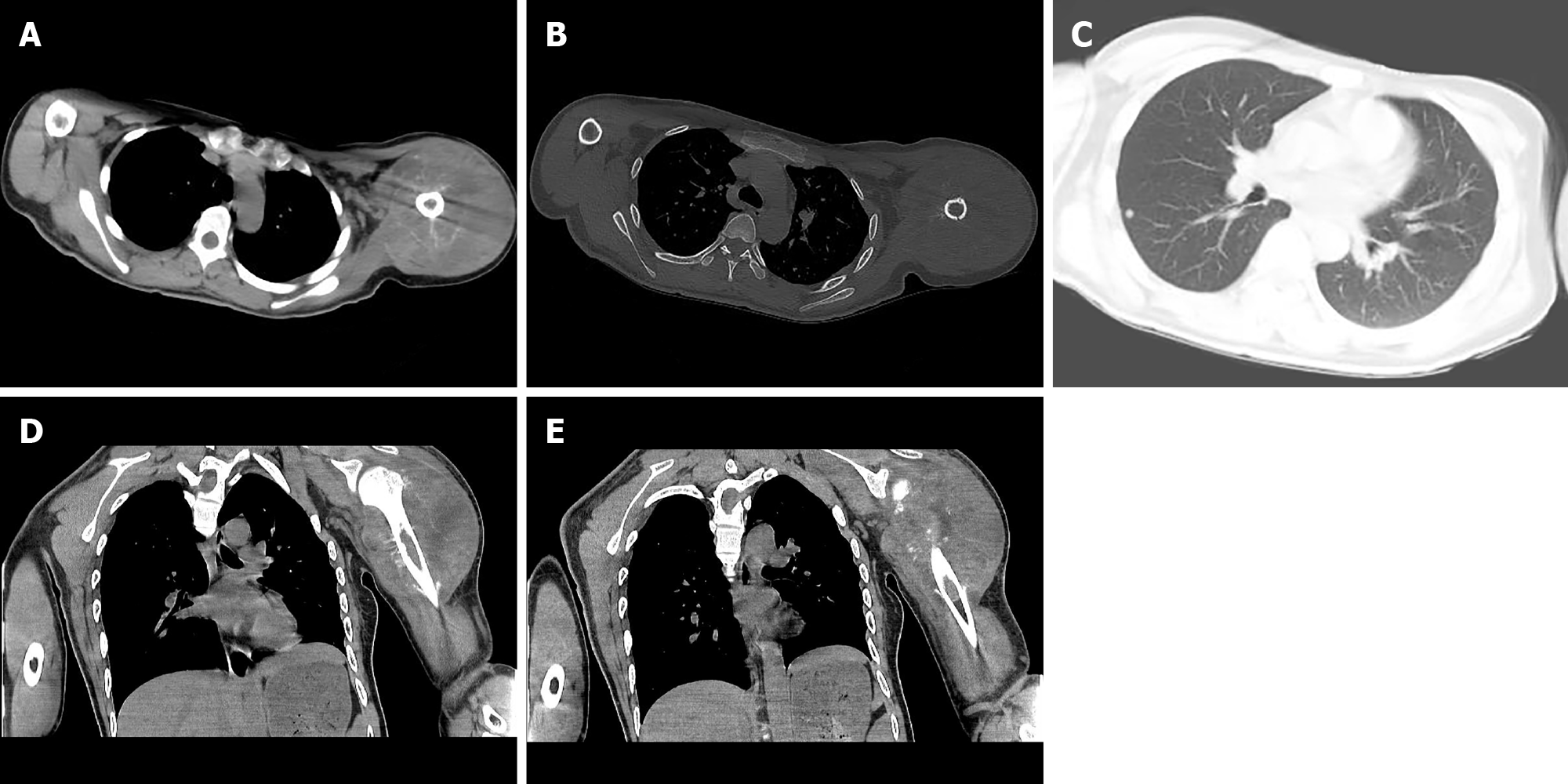

Posteroanterior shoulder joint radiography showed a linear low-density shadow at the greater tuberosity of the left humerus and small low-density flakes in the upper medullary cavity of the left humerus (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) of the left shoulder joint revealed a soft tissue mass in the left shoulder (Figure 2). Strip-like calcifications in the mass (Figure 2A), the cortical edge, and marrow cavity were seen to be invaded on axial and coronal CT images (Figure 2B, D and E), and the adjacent bone showed an insect-like zone of destruction and needle-like periosteal reaction. Thoracic CT revealed multiple small, solid, rounded nodules with clear boundaries beneath the pleura of both lungs. These were more common in the lower lobe of the right lung, and the larger nodules were approximately 6 mm in size (Figure 2C).

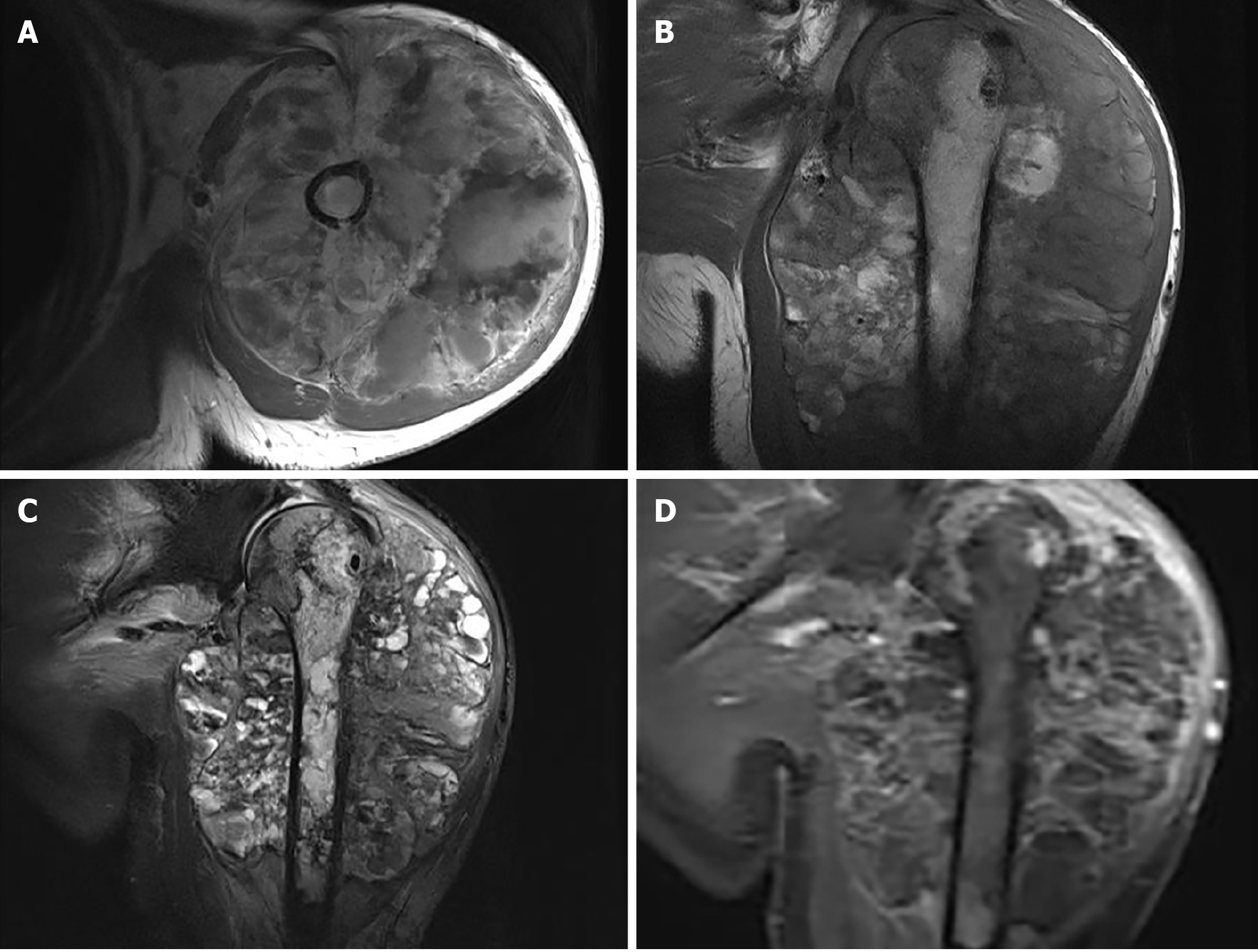

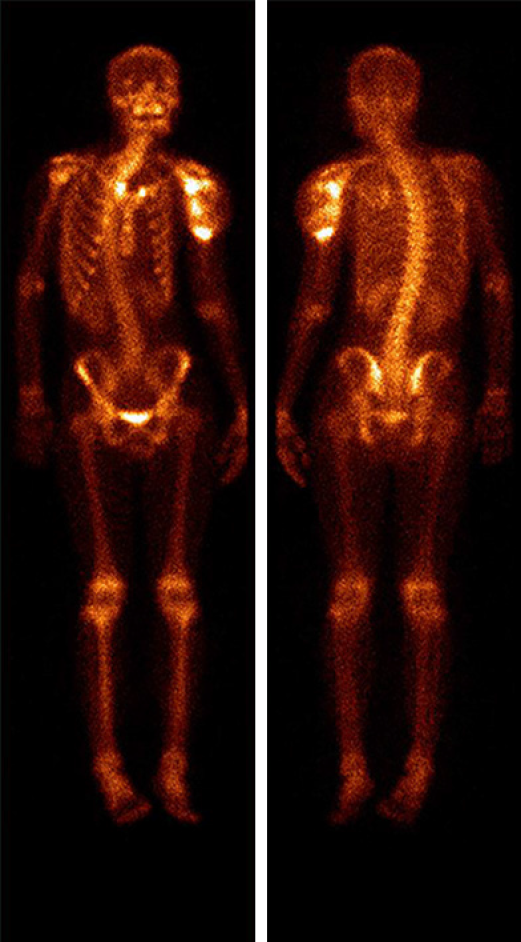

Upper arm magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was conducted to further assess the extent of the mass (Figure 3). A huge mass was observed surrounding the left humeral head and the proximal shaft of humerus. It had a clear outer boundary and a size of 10.3 cm × 10.5 cm × 13.6 cm (anterior-posterior × left-right × superior-inferior). The mass showed mixed moderate hypointensity and hyperintensity on T1-weighted images (Figure 3A and B) and mixed hyperintensity on coronal fat-saturated T2-weighted images (Figure 3C). T1-weighted images with contrast demonstrated heterogeneous enhancement of the lesion (Figure 3D). The humeral cortex was discontinuous, with worm-eaten-like bone destruction seen on the axial T1-weighted images. The inside of the cancellous bone showed irregular patches of hypointensity on coronal T1-weighted images and mixed hyperintensity on fat-saturated T2-weighted images. Based on the findings of multimodality imaging, a primary locally invasive soft tissue tumor with a pathological fracture was suspected. The patient underwent a whole-body 99mTc-methylene diphosphonate bone scan to check the condition of the other bones (Figure 4). The bone scan demonstrated clearly visible scoliosis, an abnormal distribution of radioactive label concentrations, and increased activity in the left shoulder joint and proximal humerus, corresponding to the mass seen on MRI.

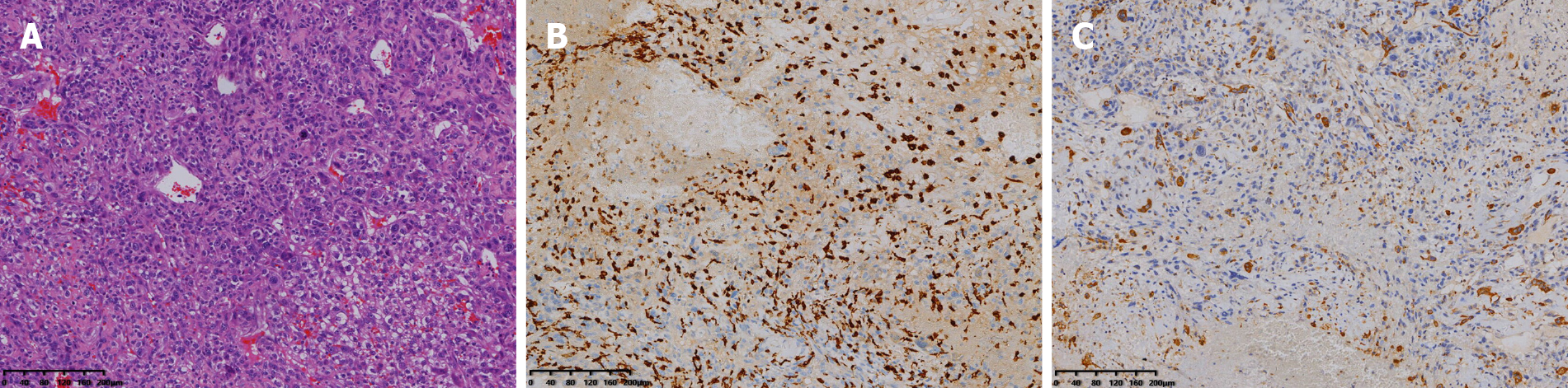

Finally, histopathology after surgery showed that the tumor was composed of polygonal mononuclear cells and multinucleated osteoclast-like giant cells (Figure 5A). Immunohistochemical staining was positive for CD163 and CD68 (Figure 5B and C), and negative for cytokeratin and S-100, corresponding to the phenotypic profile of a giant cell tumor.

Primary GCT-ST of the left proximal humerus.

After hospitalization, the left shoulder joint was punctured and approximately 10 mL of bloody fluid was withdrawn. The pain gradually increased and was not relieved after blood stasis treatment. To confirm the diagnosis, the patient was prepared to undergo a biopsy of the left shoulder lesion. During the operation, the skin, subcu

The family members refused to transfer the patient to the oncology department to continue treatment and asked to discharge the patient to a local hospital for treatment. Telephone follow-up conducted 3 mo later found that the patient’s lung nodules had increased. After 6 mo, the patient was lost to follow-up by telephone.

GCT-ST is an extremely rare primary soft tissue tumor that sometimes leads to local recurrence and rarely to distant metastasis. The World Health Organization classifies these types of tumors as GCT-STs with low malignant potential or as malignant GCT-STs. Until now, etiological factors for GCT-STs have not been identified. In clinical practice, GCT-ST is known to be extremely rare and to have unpredictable beha

Given its appearance on a bone scan and other imaging modalities, the differential diagnosis should include epithelioid sarcoma and extraskeletal osteosarcoma. Epi

As this case demonstrates, the possibility of GCT-ST should be considered when interpreting masses in limbs that exhibit calcification and bone destruction. Here, we present a rare case of a malignant GCT-ST in the upper left arm of an adolescent. The lesion was suspected on CT and was well characterized by MRI.

The authors acknowledge the contribution of all investigators at all participating study sites.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: D'Orazi V S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Yuan YY

| 1. | Mensah D, Chhantyal K, Lu YX, Li ZY. Malignant Giant Cell Tumor of Soft Tissue: A Case Report of Intramuscular Malignant Giant Cell Carcinoma of the Tensor Fasciae Latae. J Orthop Case Rep. 2019;9:70-73. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Mavrogenis AF, Tsukamoto S, Antoniadou T, Righi A, Errani C. Giant Cell Tumor of Soft Tissue: A Rare Entity. Orthopedics. 2019;42:e364-e369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lee JC, Liang CW, Fletcher CD. Giant cell tumor of soft tissue is genetically distinct from its bone counterpart. Mod Pathol. 2017;30:728-733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | O'Connell JX, Wehrli BM, Nielsen GP, Rosenberg AE. Giant cell tumors of soft tissue: a clinicopathologic study of 18 benign and malignant tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:386-395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chen H, Fan Q, Su M. Mediastinal 99mTc-Methylene Diphosphonate Accumulation in a Patient With Primary Mediastinal Soft Tissue Giant Cell Tumor. Clin Nucl Med. 2020;45:477-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hu Q, Peng J, Xia L. Recurrent primary mediastinal giant cell tumor of soft tissue with radiological findings: a rare case report and literature review. World J Surg Oncol. 2017;15:137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hafiz SM, Bablghaith ES, Alsaedi AJ, Shaheen MH. Giant-cell tumors of soft tissue in the head and neck: A review article. Int J Health Sci (Qassim). 2018;12:88-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kishi S, Monma H, Hori H, Kinugasa S, Fujimoto M, Nakamura T. First Case Report of a Huge Giant Cell Tumor of Soft Tissue Originating from the Retroperitoneum. Am J Case Rep. 2018;19:642-650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |