Published online May 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i14.3442

Peer-review started: December 12, 2020

First decision: January 27, 2021

Revised: February 8, 2021

Accepted: March 3, 2021

Article in press: March 3, 2021

Published online: May 16, 2021

Processing time: 138 Days and 0.1 Hours

How to treat infantile hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection remains a controversial issue. The nucleoside analogue lamivudine (LAM) has been approved to treat children (2 to 17 years old) with chronic hepatitis B. Here, we aimed to investigate the benefit of LAM treatment in infantile hepatitis B.

A 4-mo-old infant born to a hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)-positive woman was found to be infected by HBV during a health checkup. Liver chemistry and HBV seromarker tests showed alanine aminotransferase of 106 U/L, HBsAg of 685.2 cut-off index, hepatitis B “e” antigen of 1454.0 cut-off index, and HBV DNA of > 1.0 × 109 IU/mL. LAM treatment (20 mg/d) was initiated, and after 19 mo, serum HBsAg was entirely cleared and hepatitis B surface antibody was present. The patient received LAM treatment for 2 years in total and has been followed for 3 years. During this period, serum hepatitis B surface antibody has been persistently positive, and serum HBV DNA was undetectable.

Early treatment of infantile hepatitis B with LAM could be safe and effective.

Core Tip: We report a case of infantile hepatitis B that was successfully treated with lamivudine. In addition, we review the clinical characteristics and laboratory tests and compare them with previously reported cases. Lamivudine is safe and effective in the treatment of infantile hepatitis B, and this case report may contribute to the development of relevant clinical guidelines.

- Citation: Zhang YT, Liu J, Pan XB, Gao YD, Hu YF, Lin L, Cheng HJ, Chen GY. Successful treatment of infantile hepatitis B with lamivudine: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(14): 3442-3448

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i14/3442.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i14.3442

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a hepatotropic DNA virus that chronically infects approximately 240 million people worldwide[1]. The majority of people with chronic hepatitis B are infected at birth or in early childhood. Nearly 2 million children under the age of 5 years are newly infected with HBV every year, mainly through mother-to-infant transmission (MTIT)[2]. Reportedly, 80%-90% of infants (< 1 year old) infected by HBV will subsequently develop chronic hepatitis B; in comparison, 20%-30% of children infected between 1 and 5 years old and < 5% of adults will progress to chronic hepatitis B[3]. The main characteristics of infantile HBV infection are high replication and low inflammation during the perinatal period and childhood. Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), hepatitis B “e” antigen (HBeAg), and high HBV DNA load can be detected in the serum, and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) is normal or slightly elevated[4]. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases has already recommended antiviral treatment for children (2 to 18 years old) with chronic hepatitis B[5]. However, because of uncertainty of the natural history of chronic hepatitis B in infants, there is no consensus treatment guidelines available for children under the age of 1 year, which puts doctors in a difficult position when trying to determine the most appropriate clinical practice.

The antiviral compound lamivudine (LAM) is a dideoxynucleoside analog that is a reverse transcriptase inhibitor with great antiviral activity against both human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and HBV. It is utilized in combination with other drugs to treat human immunodeficiency virus infected patients under 3 years old, and it can also be used as a single drug to treat HBV infections, inhibiting the replication of HBV[6]. In 2019, a meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of LAM in preventing MTIT of HBV led to the authors’ strongly recommending use of LAM to prevent vertical transmission of HBV in pregnant women with HBV DNA > 1.0 × 106 IU/mL. LAM was safe for both mothers and fetuses[7].

Here, we report a case of infantile hepatitis B treated with LAM. In this case, a baby infected with HBV through MTIT received LAM at 4 mo of age. Serum HBsAg was entirely cleared, and seroconversion was achieved after 19 mo of antiviral therapy. There were no side effects found during the follow-up, which indicated that LAM could be safe and effective in the early treatment of hepatitis B in infants under 1 year old.

A 4-mo-old baby boy was hospitalized for HBsAg positivity and abnormal serological indicators of liver function found in a health checkup.

The patient had no obvious symptoms of discomfort at the time of admission.

The patient had no history of drug exposure. Furthermore, human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis A, C, and E, autoimmune hepatitis, Wilson’s disease, and other liver-related diseases were excluded.

HBV seromarker tests in the patient’s mother showed HBsAg > 300 ng/mL, HBeAg 82.79 PEIU/mL, and HBV DNA 6.47 × 107 IU/mL. The mother did not take any antiviral drug in the third trimester of pregnancy to block HBV. The infant was injected with hepatitis B immunoglobulin at birth and was vaccinated against hepatitis B at 0 and 1 mo after birth. He was breastfed for 3 mo after birth.

The patient’s physical examination was unremarkable.

Laboratory examination data are shown in Table 1. Notably, the ALT level was 106 U/L and aspartate aminotransferase level was 107 U/L. HBsAg, HBeAg, and hepatitis B core antibody (HBcAb) were positive, and HBV DNA load was > 109 IU/mL. The patient's serum HBV markers were examined with the Roche Cobas E601 electrochemical luminescence analyzer and associated kit (Roche diagnostic, Basel, Switzerland). HBsAg > 1 cut-off index (COI) is positive. Hepatitis B surface antibody (HBsAb) > 10 IU/L is positive. HBeAg > 1 COI is positive. Hepatitis B "e" antibody (HBeAb) < 1 COI is positive. HBcAb < 1 COI is positive. HBV DNA was quantified by real-time Taqman PCR using the Roche LightCycler480 (Roche diagnostic, Basel, Switzerland) and matched kit with detection limit of 1.0 × 102 IU/mL.

| Serum marker (unit) | Actual value | Reference range |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 106 | 1-52 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 107 | 1-40 |

| HBsAg (COI) | 685.2 | < 1 |

| HBsAb (mIU/mL) | < 2 | < 10 |

| HBeAg (COI) | 1454.0 | < 1 |

| HBeAb (COI) | 11.89 | > 1 |

| HBcAb (COI) | 0.009 | > 1 |

| HBcAb-IgM (COI) | 2.07 | < 1 |

| HBV DNA (IU/mL) | > 1.0 × 109 | < 1.0 × 102 |

According to the laboratory examinations and family history, the infant was diagnosed with HBV infection acquired through MTIT.

Our patient was treated with 20 mg/d LAM for HBV infection after informed consent was obtained from his mother.

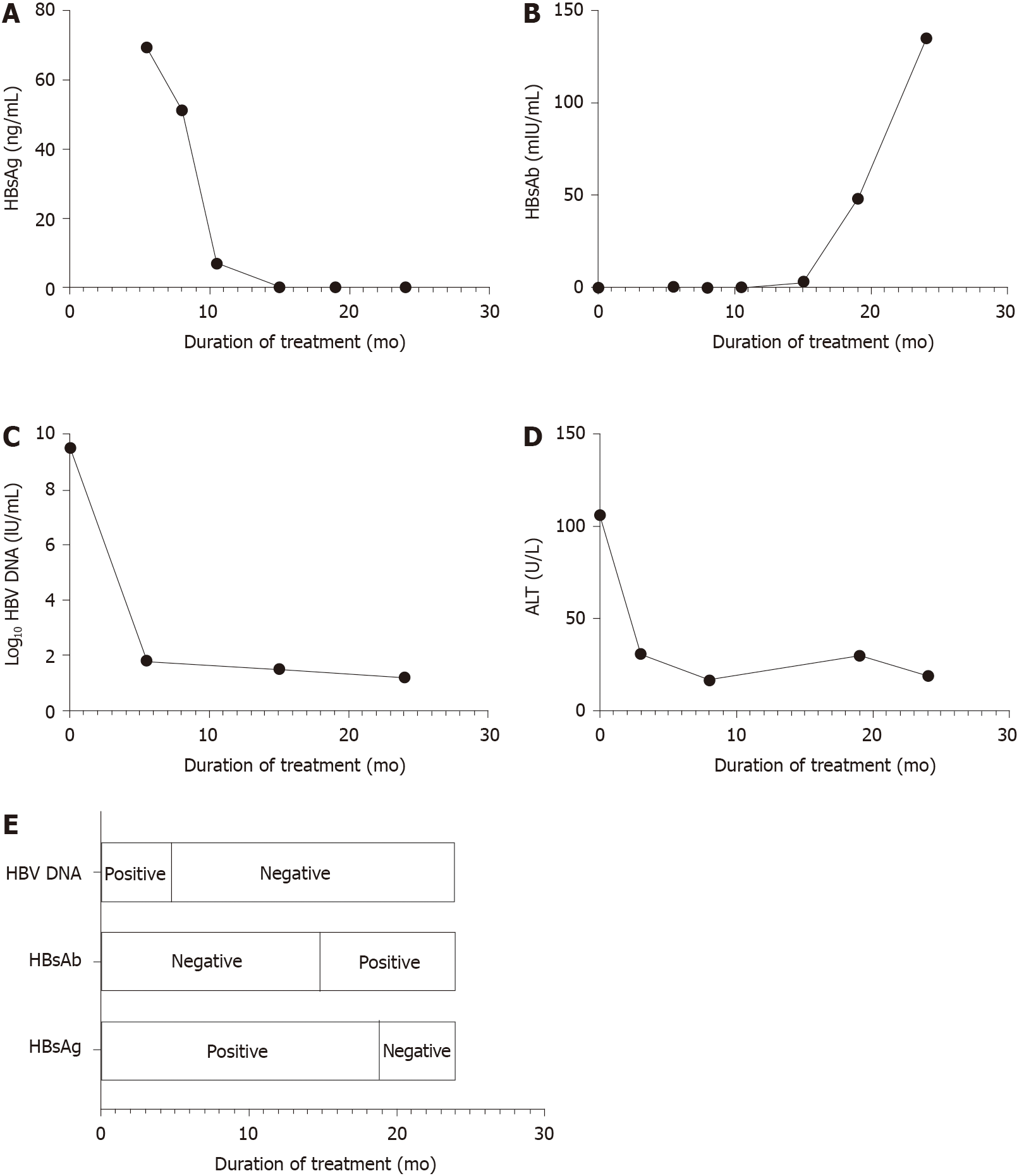

After 3 mo of antiviral treatment, the patient's serum ALT (38 U/L) dropped into the normal range. HBV DNA load (< 1.0 × 102 IU/mL) was undetectable after 5 mo of treatment. After 19 mo of treatment, HBsAg was completely cleared, and HBsAb level increased to 48.625 mIU/mL. HBeAg was entirely cleared, and seroconversion was achieved after 5 mo of antiviral therapy.

The patient stopped using LAM 2 years after initiation of antiviral therapy and has been followed for 3 years. In February 2020, he received another booster injection of hepatitis B vaccine. There were no side effects and no evidence of HBV reinfection during the antiviral treatment. The boy’s last serological indicators are shown in Table 2, and HBV DNA, HBsAg, and HBeAg are all undetectable. Figure 1 depicts the dynamic changes of serum HBsAg, HBsAb, log10 HBV DNA, and ALT during the treatment. Blood sampling schedule of the patient is shown in Table 3. It should be noted that due to the different detection methods, the serum HBsAg level of the patient on admission and during treatment were not comparable. In the follow-up tests, Immunalysis ELISA assay was used to test serum HBV markers on a Tecan Freedom EVOlyzer platform (Swiss Tecan Company RSP150/8 pretreatment system and Germany Dade Behring company produces the BEIII post-processing system) according to the manufacturer’s specifications. The kit was purchased from Ink New Technology (Xiamen) Co., Ltd. HBsAg > 0.5 ng/mL, HBsAb > 10 mIU/mL, HBeAg > 0.5 PEIU/mL, HBeAb > 0.2 PEIU/mL, and HBcAb > 0.9 IU/mL were considered positive. HBV DNA was quantified by PCR-fluorescent probe method using the Thermo Fisher ABI7500, United States, and the kit was purchased from Da An Gene Co., Ltd. of Sun Yat-Sen University with detection limit of 1.0 × 102 IU/mL. In the last test, serum HBV markers were quantified with Cobas E411 (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). HBsAg > 0.05 IU/mL, HBsAb > 10 mIU/mL, HBeAg > 0.11 PEIU/mL, HBeAb < 1.1 PEIU/m, and HBcAb < 1.1 IU/mL were considered positive. HBV DNA was detected by real-time Taqman PCR on the ABI Prism 7000 system (Applied Biosystems, Forster City, CA, United States) and assayed with the matched kit with detection limit of 30 IU/mL.

| Serum marker (unit) | Actual value | Reference range |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 18 | 1-52 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 33 | 1-40 |

| HBsAg (IU/mL) | < 0.03 | < 0.05 |

| HBsAb (mIU/mL) | > 1000 | 0.0-10.00 |

| HBeAg (PEIU/mL) | < 0.01 | 0.00-0.11 |

| HBeAb (PEIU/mL) | < 0.1 | > 1.10 |

| HBcAb (IU/mL) | < 0.1 | > 1.10 |

| HBV DNA (IU/mL) | < 30 | < 30 |

| White blood cell (109/L) | 5.95 | 4.0-10.0 |

| Neutrophil (109/L) | 2.66 | 2.00-7.00 |

| Red blood cell (1012/L) | 4.16 | 3.50-5.50 |

| Platelet (109/L) | 306.0 | 100.0-300.0 |

| Date | Item |

| December 14, 2015 | ALT, HBsAg, HBsAb, HBeAg, HBeAb, HBV DNA |

| April 1, 2016 | ALT |

| May 3, 2016 | HBsAg, HBsAb, HBeAg, HBeAb, HBV DNA |

| August 11, 2016 | ALT, HBsAg, HBsAb, HBeAg, HBeAb, HBV DNA |

| November 2, 2016 | HBsAg, HBsAb, HBeAg, HBeAb |

| March 22, 2017 | HBsAg, HBsAb, HBeAg, HBeAb, HBV DNA |

| July 20, 2017 | ALT, HBsAg, HBsAb, HBeAg, HBeAb |

| December 11, 2017 | ALT, HBsAg, HBsAb, HBeAg, HBeAb, HBV DNA |

| April 8, 2018 | HBsAg, HBsAb, HBeAg, HBeAb |

| July 31, 2018 | HBsAg, HBsAb, HBeAg, HBeAb |

| January 6, 2019 | HBsAg, HBsAb, HBeAg, HBeAb |

| November 27, 2019 | ALT, HBsAg, HBsAb, HBeAg, HBeAb, HBV DNA |

| July 2, 2020 | ALT, HBsAg, HBsAb, HBeAg, HBeAb, HBV DNA |

A previous study has shown that the rate of spontaneous loss of HBsAg in Asian infants less than 1 year old is extremely low (between 0.5% and 1.4%)[8]. Our case showed a 4-mo-old infant born to an HBsAg-positive mother who was infected by HBV; serum ALT level on admission was more than twice the normal upper limit, and HBV DNA was > 109 IU/mL. Nineteen months after initiating antiviral therapy (LAM), serum HBsAg and HBV DNA were entirely cleared and seroconversion was achieved.

The concept of early treatment for infantile hepatitis B has been reported in recent years and has proven efficacy[9-11]. For infantile hepatitis B, published studies mainly involve LAM therapy. Previously, three cases of infants younger than 1 year old with acute severe hepatitis B, whose serum was HBsAg-positive and HBeAg-negative, were reported. Their serum HBsAg successfully turned to negative within 9 mo after early application of LAM (at initial doses of 8 mg/kg and 3-4 mg/kg, daily) and adjuvant support therapy[12-14]. In 2019, a study by Zhu et al[15] showed early antiviral therapy with LAM (4 mg/kg, daily) contributed to the rapid negative conversion of serum HBsAg in infants under 1 year old with HBV DNA > 105 IU/mL and ALT more than two times the upper limit of normal. Bertoletti et al[9], however, offered a different perspective. They suggested that early antiviral therapy had no role in patients' ALT levels and that the clinical endpoints of the study should not be limited to “obtaining a higher serum HBsAg conversion rate”. Emphasis should be placed on early treatment and the adoption of new treatment strategies to reduce hepatocyte infection and HBV DNA integration in order to avoid the long-term effects of HBV infection.

In this case, HBsAg was completely cleared and HBsAb levels were quantifiably increased after 19 mo of LAM treatment. The immune response to HBV infection in infants has been a controversial topic in recent years. Traditionally, the infant’s immune system is considered to be physically immature, and infants are more vulnerable to severe infections than adults. HBV induces an “immune tolerance state” in the host through transplacental HBeAg to produce persistent infections[5]. Recently, however, there is growing evidence showing that infants are neither “immature” nor “immunodeficient”. The innate immune system could display memory features immediately following birth, and specific T cells in infants have the ability to resist viral infection. In other words, the immune system of a newborn is trained or matured and can actually produce a broad-cross protective response to viral antigens[16]. On the other hand, the infant’s liver volume is small, and the duration of HBV infection is short. Thus, the absolute amount of HBsAg and HBV DNA load are low, and infection of new hepatocytes by HBV is avoided. The plasticity of the early life immune system makes it amenable to therapeutic interventions to combat infection[17]. Therefore, infants with hepatitis B may have better therapeutic outcomes than adults with antiviral therapy.

Nucleoside/nucleotide analogues are the main drugs for the treatment of HBV infection in children. In the treatment of infantile hepatitis B, safety is an important issue that cannot be ignored. Like adults, nucleoside/nucleotide analogues can also cause different degrees of adverse reactions, such as myopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, and lactic acidosis. Some of these adverse events can be attributed to their effects on mitochondrial dysfunction, and most of the cases have involved LAM and telbivudine treatment. There has been no increase in reported fetal adverse events with LAM treatment[18]. Fortunately, in this case, no adverse reactions occurred throughout the treatment and follow-up period, which is consistent with the findings of Zhu et al[15].

Physical examination during pregnancy and timely antiviral therapy are still the main measures to prevent MTIT of HBV. According to several previous reports, HBsAg conversion in infants infected with HBV is higher than that in adults. This was true in the case presented here, and there was no recurrence during the follow-up. In other words, the infant achieved clinical recovery, which indicates that the early application of LAM in the treatment of infants under 1 year old with MTIT of HBV is safe and effective. This case may provide insight into possible adjustment of the current treatment guidelines. More cases are still needed to assess the efficacy of LAM treatment for infantile hepatitis B.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Yang SS S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Schweitzer A, Horn J, Mikolajczyk RT, Krause G, Ott JJ. Estimations of worldwide prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a systematic review of data published between 1965 and 2013. Lancet. 2015;386:1546-1555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1806] [Cited by in RCA: 1997] [Article Influence: 199.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 2. | Polaris Observatory Collaborators. Global prevalence, treatment, and prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in 2016: a modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3:383-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1260] [Cited by in RCA: 1214] [Article Influence: 173.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | El-Raziky ME, Fouad HM, Abd Elkhalak NS, Ghobrial CM, El-Karaksy HM. Paediatric chronic hepatitis B virus infection: are children too tolerant to treat? Acta Paediatr. 2019;108:1144-1150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hsu HY, Chang MH, Hsieh KH, Lee CY, Lin HH, Hwang LH, Chen PJ, Chen DS. Cellular immune response to HBcAg in mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis B virus. Hepatology. 1992;15:770-776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Terrault NA, Lok ASF, McMahon BJ, Chang KM, Hwang JP, Jonas MM, Brown RS Jr, Bzowej NH, Wong JB. Update on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidance. Hepatology. 2018;67:1560-1599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2290] [Cited by in RCA: 2840] [Article Influence: 405.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Johnson MA, Moore KH, Yuen GJ, Bye A, Pakes GE. Clinical pharmacokinetics of lamivudine. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1999;36:41-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Khalighinejad P, Alavian SM, Fesharaki MG, Jalilianhasanpour R. Lamivudine's efficacy and safety in preventing mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B: A meta-analysis. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2019;30:66-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Della Corte C, Nobili V, Comparcola D, Cainelli F, Vento S. Management of chronic hepatitis B in children: an unresolved issue. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:912-919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bertoletti A, Gill US, Kennedy PTF. Early treatment of chronic hepatitis B in children: Everything to play for? J Hepatol. 2020;72:802-803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | D'Antiga L, Aw M, Atkins M, Moorat A, Vergani D, Mieli-Vergani G. Combined lamivudine/interferon-alpha treatment in "immunotolerant" children perinatally infected with hepatitis B: a pilot study. J Pediatr. 2006;148:228-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zoulim F, Mason WS. Reasons to consider earlier treatment of chronic HBV infections. Gut. 2012;61:333-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chen CY, Ni YH, Chen HL, Lu FL, Chang MH. Lamivudine treatment in infantile fulminant hepatitis B. Pediatr Int. 2010;52:672-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Laubscher B, Gehri M, Roulet M, Wirth S, Gerner P. Survival of infantile fulminant hepatitis B and treatment with Lamivudine. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;40:518-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chotun N, Strobele S, Maponga TG, Andersson MI, Nel ER. Successful Treatment of a South African Pediatric Case of Acute Liver Failure Caused by Perinatal Transmission of Hepatitis B. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2019;38:e51-e53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zhu S, Dong Y, Wang L, Liu W, Zhao P. Early initiation of antiviral therapy contributes to a rapid and significant loss of serum HBsAg in infantile-onset hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2019;71:871-875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hong M, Bertoletti A. Tolerance and immunity to pathogens in early life: insights from HBV infection. Semin Immunopathol. 2017;39:643-652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kollmann TR, Kampmann B, Mazmanian SK, Marchant A, Levy O. Protecting the Newborn and Young Infant from Infectious Diseases: Lessons from Immune Ontogeny. Immunity. 2017;46:350-363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 222] [Cited by in RCA: 311] [Article Influence: 38.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kayaaslan B, Guner R. Adverse effects of oral antiviral therapy in chronic hepatitis B. World J Hepatol. 2017;9:227-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |