Published online Apr 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i12.2830

Peer-review started: October 14, 2020

First decision: December 21, 2020

Revised: January 18, 2021

Accepted: March 4, 2021

Article in press: March 4, 2021

Published online: April 26, 2021

Processing time: 183 Days and 0.6 Hours

A prostatic stromal tumor is deemed to be a rare oncology condition. Based on the retrospective analysis of clinical data and scientific literature review, a case of prostatic stromal tumor was reported in this article to explore the diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of this rare disease.

The present case involved an older male patient who was admitted to our department for a medical consultation of dysuria. Serum prostate-specific antigen was 8.30 ng/mL, Ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging suggested evident enlargement of the prostate and multiple cystic developments internally. Considering that the patient was an elderly male with a poor health status, transurethral resection of the prostate was performed to improve the symptoms of urinary tract obstruction. Furthermore, based on histopathologic examination and immunohistochemical staining, the patient was pathologically diagnosed with prostatic stromal tumor. The patient did not receive any further adjuvant therapy following surgery leading to a clinical recommendation that the patient should be followed up on a long-term basis. However, during the recent follow-up assessment, the patient demonstrated recurrence of lower urinary tract symptoms and gross hematuria.

Referring to scientific literature review, we believe that the management of these lesions requires a thorough assessment of the patient. Furthermore, the treatment of prostate stromal tumors should be based on the imaging examination and pathological classification. Active surgical treatment is of great significance to the prognosis of patients, and subsequent surveillance after the treatment is warranted.

Core Tip: The pathological type of this case was very rare. Few medical reports exist, so there is still a lack of high-level evidence to diagnose and treat this type of tumor. We hope to provide evidence for the diagnosis and treatment of prostate stromal tumors in the future.

- Citation: Zhao LW, Sun J, Wang YY, Hua RM, Tai SC, Wang K, Fan Y. Prostate stromal tumor with prostatic cysts after transurethral resection of the prostate: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(12): 2830-2837

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i12/2830.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i12.2830

Prostate tumors are one of the most prevalent tumors in men, most of which are prostate cancer. However, interstitial prostate cancer accounts for only 1% of such cases[1]. Prostate stromal tumors (PST) encompass a spectrum of histologic patterns and have unique clinical behavior. In 1998, according to the degree of stromal cellularity and the presence of mitotic figures, necrosis and stromal overgrowth, Gaudin et al[2] first classified prostatic stromal tumors into two subtypes: Prostatic stromal tumors of uncertain malignant potential (STUMP) and prostatic stromal sarcoma (PSS). This classification was adopted by The World Health Organization in 2005[3] and has been clinically implemented until the present day. Most of the cases reported in the relevant literature were individual case reports lacking systematic and comprehensive research on the clinical characteristics, imaging diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of PST. In this article, the clinical data and imaging findings of a patient with PST were analyzed retrospectively in the context of the literature in an attempt to explore the diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of this rare disease.

An 87-year-old Chinese male was first admitted to our department with a 1-year history of progressive dysuria and urinary retention for 24 h.

One year ago, the patient presented with progressive dysuria, including urination hesitancy, decreased force of urination, straining, and dribbling. Although his urine flow was fine, he complained of frequent urination and nocturia. There were no odynuria and gross hematuria with no interruption of urinary stream. Even though the patient was on finasteride tablets (5 mg po qd × 1) and tamsulosin (0.2 mg po qd × 1) treatment, symptoms did not improve significantly. The patient developed acute urinary retention 24 h prior to admission.

The patient suffered from epilepsy 2 years prior to hospital admission and was currently on compound sodium valproate and valproic acid sustained release tablets (0.5 g po bid × 1) treatment. In addition, he was suffering from a poor health due to concomitant medical issues including hypertension, mild anemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and hypothyroidism, though no other medications were given to the patient for the noted additional medical conditions.

He smoked for more than 60 years but quit recently. His family history was ordinary, and there was no history of genetic heritability of cancer. The patient had no prior imaging examination of the urinary tract system.

No tenderness in the bilateral kidneys, ureters or bladder was discerned on examination. Furthermore, no evident abnormality was found in the external genitalia. Digital rectal examination (DRE) revealed normal anal sphincter tension, though with profound hyperplasia of the prostate gland at a level that the entire boundary could not be examined digitally. The prostate surface was smooth, while its internal bulk felt soft and cystic with an absent central fissure and no palpated nodule.

Serum prostate specific antigen (PSA) was 8.30 ng/mL (normal range: 0-4 ng/mL), free PSA was 3.30 ng/mL, with a total PSA/free PSA ratio of 0.398. Urine cell analysis results revealed white cell count of 2-4/high powered field (HPF) (normal range: 0-5/HPF) and red blood cell count of > 50/HPF (normal range: 0-10/HPF). Urine culture for bacteria was negative. There were no obvious abnormalities in routine blood tests, coagulation function, liver and kidney function, blood electrolytes and other blood biochemical tests.

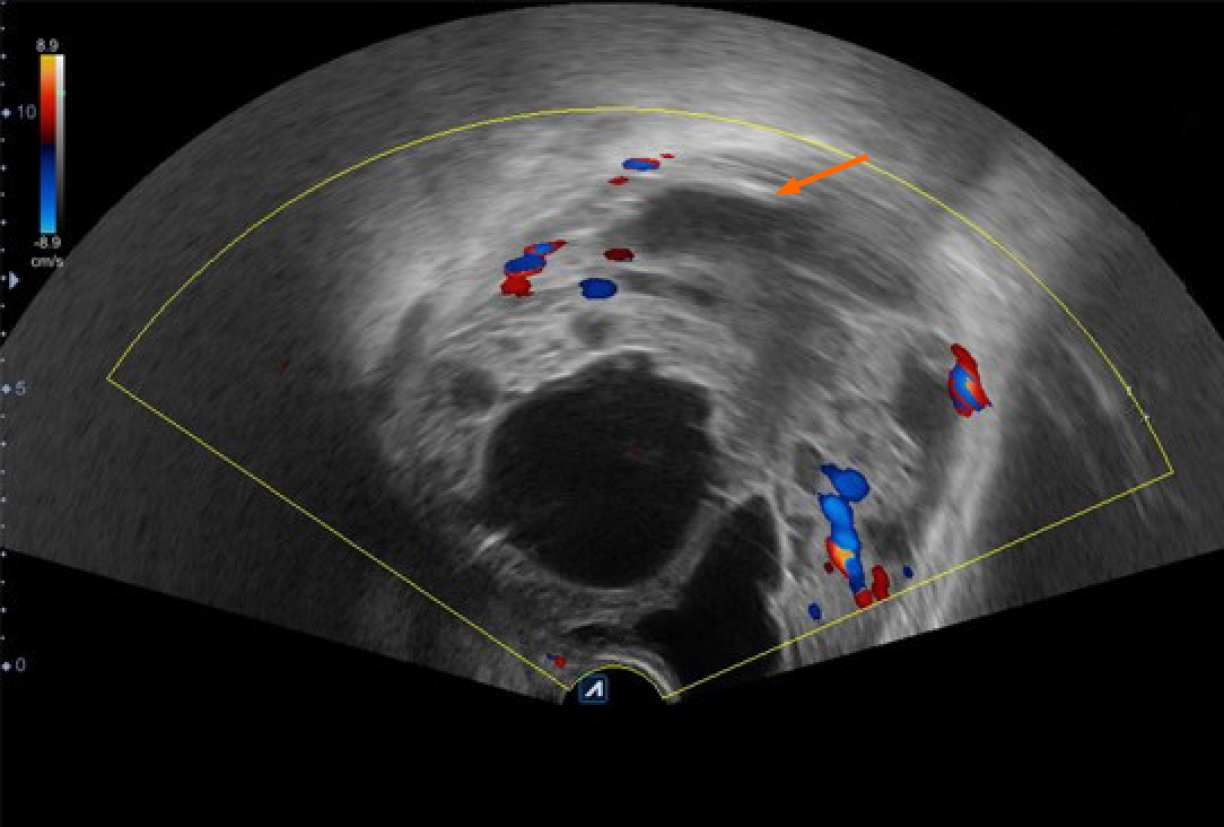

Initial chest computed tomography (CT) revealed no evident nodules in either lung field. Subsequent findings from urinary tract area color ultrasound suggested an evident, enlarged prostate sized at approximately 9.29 cm × 10.98 cm × 9.62 cm protruding into the urinary bladder. Multiple cystic, hypoechoic lesions were detected within the prostate gland. No obvious signs of blood flow were identified within the hypoechoic lesions. Prostate hyperplasia with cystic degeneration was considered (Figure 1). Magnetic resonance imaging revealed that the prostate was profoundly enlarged with resultant compression and right-sided deviation of the urinary bladder and rectum. Irregular density shadows could be seen in the prostate gland area. T2 weighted imaging revealed nonhomogeneous and height signals inside with nonhomogeneous enhancement visible (post enhancement). The prostate peripheral zone was unclear with bilateral seminal vesicles atrophied, though with no evidence of lymph node involvement in the pelvic cavity or tumor invasion to surrounding structures (Figure 2). A preliminary diagnosis of benign prostate hyperplasia with prostatic cysts was concluded.

The final diagnosis of the presented case was prostate stromal tumor with prostatic cysts.

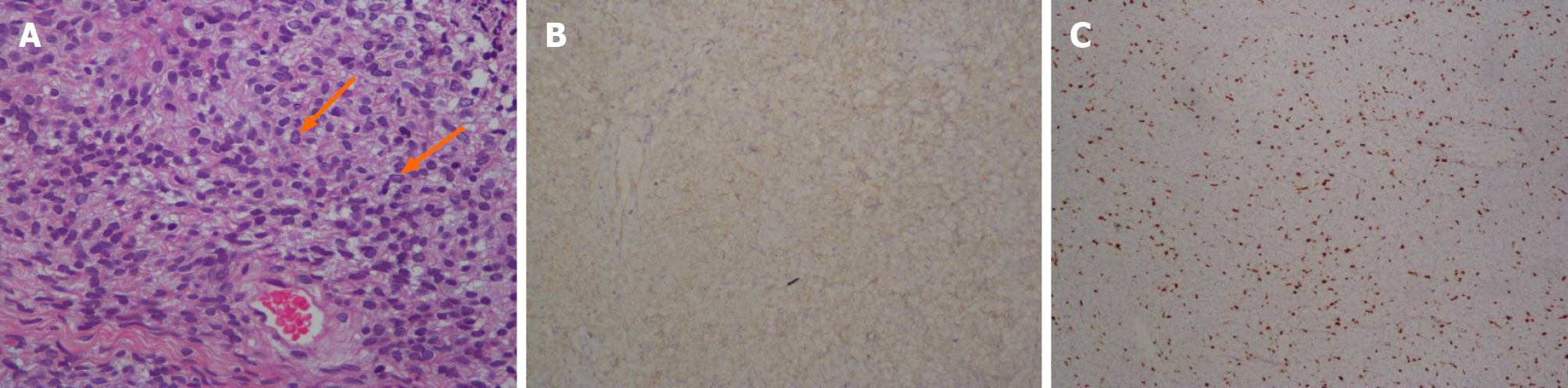

Because the patient was 87-years-old and had previous underlying diseases, including epilepsy, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and hypothyroidism together with such a profoundly enlarged prostate, the symptoms of the urinary tract obstruction were deemed as highly serious. Moreover, PSS could not be completely ruled out from diagnosis. Following consultation with family members and the patient, transurethral resection of the prostate was performed leading to the identification of multiple cystic areas filled with clear, serous fluid during surgery. Postoperative pathology revealed a large number of mesenchymal spindle cells within the cyst wall (Figure 3A), and immunohistochemistry highlighted the following: CD34 (++) (Figure 3B), CK34βE12 (+), Ki-67 (approximately 8% +) (Figure 3C), PSA (-), P504S (-) and actin (-). These analytical findings ascertained a diagnosis of prostatic stromal tumor.

Lower urinary tract symptoms of the patient were relieved after the surgery. The International Prostate Symptom Score was reduced, and the postoperative residual urine volume of the bladder was approximately 40 mL. No further adjuvant treatment was administered, and close follow-up was recommended when the patient was discharged from hospital.

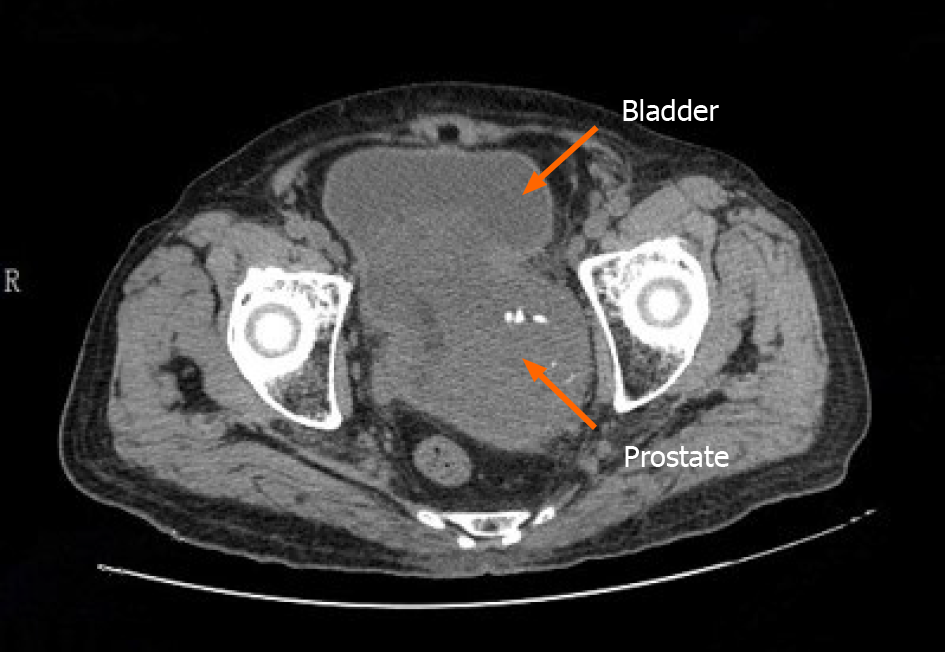

Presently, at the time of manuscript submission, the last re-examination of the patient revealed that the patient relapsed with symptoms of urinary frequency, urgency and appeared gross hematuria. A pelvic CT scan of the patient revealed that the prostate was enlarged in size and shaped irregularly. The prostate gland protruded locally into the urinary bladder area with uneven density. In addition, patchy, low-density shadows and punctate calcification could also be seen in the prostate gland, with the boundary between the prostate and bilateral seminal vesicles gland being unclear (Figure 4). We treated the patient with α-receptor blockers to improve the lower urinary tract symptoms. However, the pharmacological effect of these drugs was not satisfactory, and the patient (and his kin) was not willing to undergo the second operation. Consequently, long-term follow-up was still adopted.

Due to rare cases, the etiology and pathogenesis of PSS is still unknown, and no confirmed risk factors have been identified. The most common clinical manifestations of PST are lower urinary tract symptoms followed by DRE abnormalities, hematuria, changes in defecation habits and acute urinary retention. It is worth noting that PSA, as a specific marker of prostate cancer, lies mostly within normal range or at a slightly elevated level in patients with PST[4]. A possible reason for this could be that PSA is produced by prostatic epithelial cells, while PSTs have no obvious influence on epithelial cells. The slight increase of PSA levels may also be caused by tissue compression. The onset age of patients with PST is 17-86-years-old, with the median age being 58-years-old, and the peak age of onset being 60-70-years-old[5-9]. In this case, the patient suffered from lower urinary tract symptoms and acute urinary retention with an onset age being marginally elevated than what was reported in the literature. The PSA level was in the range of 4-10 ng/mL, total PSA/free PSA was normal, and DRE did not identify evident nodules.

Imaging examination plays an important role in early diagnosis, treatment options and relapse detection of the disease[10]. Transrectal ultrasonography can identify small masses that DRE cannot assert or masses that can easily be missed on diagnosis with a sensitivity of 90%. Pelvic CT can accurately display the size, morphology, extracapsular spread and metastasis of prostate masses, together with providing guidance for treatment recommendations of tumors based on imaging evidence. However, the CT detection rate of early pathological changes is lower than magnetic resonance imaging, where the latter is more accurate in distinguishing tumor boundaries and in identifying suspect masses as adenocarcinoma or otherwise[11]. Because our reported case was complicated with huge multiple prostatic cysts, patient manifestations present on ultrasound examination and magnetic resonance imaging were not typical.

PSS is a highly malignant PST with high local recurrence and distant metastasis rate, consequently leading to a poor long-term prognosis[12]. For patients with sarcoma characteristics at first visit, radical prostatectomy should be seriously considered[6,8]. Presently, it is believed that the presence of sarcoma in tissues is an important factor in the prognosis of PST[6,13,14]. Surgical resection is the preferred treatment method for PSS. Surgical treatment should focus on optimizing the control of lesions to minimize the risk of positive surgical margin. It is reported that robot-assisted surgery is likely to achieve better surgical results[15].

STUMP is a unique mesenchymal tumor associated with prostate sarcoma, which can occur simultaneously or subsequently, showing unpredictable biological properties. STUMP is usually difficult to distinguish from benign prostatic hyperplasia in clinical diagnosis. The two conditions overlap in patient age, symptom presentation profiles and epithelial-mesenchymal cross changes in pathology. Epithelial hyperplasia takes an absolute advantage in particular cases so that the diagnosis of STUMP will be concealed and misdiagnosed as benign prostatic hyperplasia[16]. STUMP tumors are typically recognized as neoplasms even if they do not behave aggressively because it is reported that despite aggressive local resection or radical surgery, 46% of patients with prostatic STUMP will still develop local recurrence with 5% of patients progressing to PSS or suffer from distant metastasis[6]. Matsuyama et al[17] hypothesized that the diagnosis of STUMP is questionable before radical prostatectomy is performed to obtain complete pathological tissues. Furthermore, because STUMP tumors tend to grow rapidly with a high recurrence rate, it is not suitable to perform resection by transurethral resection, and repeated transurethral resection procedures could possibly transform such tumors from STUMP to PSS. Consequently, the emerging school of thought is that radical prostatectomy is a more effective therapeutic option[16,18-20].

In essence, in the case of STUMP patient management, the latest concordance in clinical treatment options describes the need to conduct comprehensive evaluations and share decision making for these patients[21]. The comprehensive evaluation should include the patient’s age, palpability of the lesions during DRE with extension of the lesion following tissue sampling and imaging studies in combination with the classification and immunohistochemical results of pathological tissues obtained from prostate biopsy or other surgical procedures. Because published case series are few and far between, there is no corresponding protocol or guideline that can be easily implemented in the management of all STUMP tumors. Stemming from this, management options range from patient observation to radical and extensive surgical resection.

The treatment also requires a thorough evaluation of the body of evidence for malignancy potential, especially regarding undetected sarcomas with subsequent treatment options selected following shared decision-making with the patient. Bidikov et al[21] also suggested that when determining the treatment plan, the size and extent of the lesion, patient age, comorbidities and patient preferences should be considered. In addition, a multidisciplinary recommendation and determination of active surgical treatment for younger patients should be adopted with colleagues from medical oncology and radiation oncology to make joint decisions. However, if STUMP tumors without evidence of sarcoma are confirmed on final surgical pathology, then it is deemed safe to recommend close follow-up without adjuvant therapy, such as monitoring of the lesion with a cystoscope and transrectal ultrasonography following transurethral resection is also an option to attain local control of low-grade tumors[22].

Although local radiotherapy, chemotherapy and endocrine therapy for PST have been reported, the curative effect is still a matter of debate. The treatment effect is difficult to evaluate and lacks evidence-based medical basis due to the rarity of these tumors.

This case was confirmed as PST with prostatic cysts pathologically after the transurethral resection of the prostate. It was associated with tolerable functional outcomes a few months after surgery. Due to the limitations of the patient’s poor health status and selection of the patient in this case, transurethral resection of the prostate was the only palliative treatment to improve patient symptoms. The patient developed recurrence of lower urinary tract symptoms and gross hematuria soon after surgery, for which no further active treatment strategy was implemented. Active surgical treatment is of great significance to patient prognosis. Because only one case was described in this case study, additional PST cases and their close, multidisciplinary clinical management can shed further light onto this rare cancer condition.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ahmed M S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Chang YS, Chuang CK, Ng KF, Liao SK. Prostatic stromal sarcoma in a young adult: a case report. Arch Androl. 2005;51:419-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Gaudin PB, Rosai J, Epstein JI. Sarcomas and related proliferative lesions of specialized prostatic stroma: a clinicopathologic study of 22 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:148-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chan TY. World Health Organization classification of tumours: Pathology & genetics of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs. Urology. 2005;65:214-215. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | De Berardinis E, Busetto GM, Antonini G, Giovannone R, Di Placido M, Magliocca FM, Di Silverio A, Gentile V. Incidental prostatic stromal tumor of uncertain malignant potential (STUMP): histopathological and immunohistochemical findings. Urologia. 2012;79:65-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cavaliere E, Alaggio R, Castagnetti M, Scarzello G, Bisogno G. Prostatic stromal sarcoma in an adolescent: the role of chemotherapy. Rare Tumors. 2014;6:5607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Herawi M, Epstein JI. Specialized stromal tumors of the prostate: a clinicopathologic study of 50 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:694-704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bierhoff E, Vogel J, Benz M, Giefer T, Wernert N, Pfeifer U. Stromal nodules in benign prostatic hyperplasia. Eur Urol. 1996;29:345-354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hossain D, Meiers I, Qian J, MacLennan GT, Bostwick DG. Prostatic stromal hyperplasia with atypia: follow-up study of 18 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1729-1733. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Osaki M, Osaki M, Takahashi C, Miyagawa T, Adachi H, Ito H. Prostatic stromal sarcoma: case report and review of the literature. Pathol Int. 2003;53:407-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Probert JL, O'Rourke JS, Farrow R, Cox P. Stromal sarcoma of the prostate. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2000;26:100-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Muglia VF, Saber G, Maggioni G Jr, Monteiro AJ. MRI findings of prostate stromal tumour of uncertain malignant potential: a case report. Br J Radiol. 2011;84:e194-e196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sexton WJ, Lance RE, Reyes AO, Pisters PW, Tu SM, Pisters LL. Adult prostate sarcoma: the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center Experience. J Urol. 2001;166:521-525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mokhtari M, Homayoun M, Yazdan Panah S. The Prevalence of Prostatic Stromal Tumor of Uncertain Malignant Potential in Specimens Diagnosed as Prostatic Hyperplasia. Arch Iran Med. 2016;19:488-490. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Hansel DE, Herawi M, Montgomery E, Epstein JI. Spindle cell lesions of the adult prostate. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:148-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mao QQ, Wang S, Wang P, Qin J, Xia D, Xie LP. Treatment of prostatic stromal sarcoma with robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy in a young adult: A case report. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:2542-2544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Colombo P, Ceresoli GL, Boiocchi L, Taverna G, Grizzi F, Bertuzzi A, Santoro A, Roncalli M. Prostatic stromal tumor with fatal outcome in a young man: histopathological and immunohistochemical case presentation. Rare Tumors. 2010;2:e57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Matsuyama S, Nohara T, Kawaguchi S, Seto C, Nakanishi Y, Uchiyama A, Ishizawa S. Prostatic Stromal Tumor of Uncertain Malignant Potential Which Was Difficult to Diagnose. Case Rep Urol. 2015;2015:879584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bostwick DG, Hossain D, Qian J, Neumann RM, Yang P, Young RH, di Sant'agnese PA, Jones EC. Phyllodes tumor of the prostate: long-term followup study of 23 cases. J Urol. 2004;172:894-899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Morikawa T, Goto A, Tomita K, Tsurumaki Y, Ota S, Kitamura T, Fukayama M. Recurrent prostatic stromal sarcoma with massive high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:330-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Musser JE, Assel M, Mashni JW, Sjoberg DD, Russo P. Adult prostate sarcoma: the Memorial Sloan Kettering experience. Urology. 2014;84:624-628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bidikov L, Maroni P, Kim S, Crawford ED. 67-year-old Male with Prostatic Stromal Tumor of Uncertain Malignant Potential. Oncology (Williston Park). 2019;33. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Bannowsky A, Probst A, Dunker H, Loch T. Rare and challenging tumor entity: phyllodes tumor of the prostate. J Oncol. 2009;2009:241270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |