Published online Apr 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i12.2791

Peer-review started: November 29, 2020

First decision: December 21, 2020

Revised: December 31, 2020

Accepted: February 19, 2021

Article in press: February 19, 2021

Published online: April 26, 2021

Processing time: 136 Days and 15.6 Hours

Malignant pheochromocytoma with cerebral and skull metastasis is a very rare disease. Combining our case with 16 previously reported cases identified from a PubMed search, an analysis of 17 cases of malignant cerebral pheochromocytoma was conducted. This literature review aimed to provide information on clinical manifestations, radiographic and histopathological features, and treatment strategies of this condition.

A 60-year-old man was admitted with a progressive headache and enlarging scalp mass lasting for 3 mo. Radiographic images revealed a left temporal biconvex-shaped epidural mass and multiple lytic lesions. The patient underwent a left temporal craniotomy for resection of the temporal tumor. Histopathological analysis led to identification of the mass as malignant pheochromocytoma. The patient’s symptoms were alleviated at the postoperative 3-mo clinical follow-up. However, metastatic pheochromocytoma lesions were found on the right 6th rib and the 6th to 9th thoracic vertebrae on a 1-year clinical follow-up computed tomography scan.

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy and histopathological examination are necessary to make an accurate differential diagnosis between malignant cerebral pheochromocytoma and meningioma. Surgery is regarded as the first choice of treatment.

Core Tip: Malignant pheochromocytoma with cerebral and skull metastasis is a very rare disease. We present the case of a 60-year-old male patient with malignant cerebral and skull pheochromocytoma who underwent surgical resection. A literature review was performed to provide information on clinical manifestations, radiographic and histopathological features, and treatment strategies of this condition. Clinical features may be similar between malignant cerebral pheochromocytoma and meningioma because they have a strong relationship in terms of genetic origin. Magnetic resonance imaging spectroscopy and histopathological examination are necessary to make an accurate differential diagnosis between malignant cerebral pheochromocytoma and meningioma. Different treatment strategies are discussed, including surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy.

- Citation: Chen JC, Zhuang DZ, Luo C, Chen WQ. Malignant pheochromocytoma with cerebral and skull metastasis: A case report and literature review. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(12): 2791-2800

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i12/2791.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i12.2791

Pheochromocytomas are rare catecholamine-secreting neuroendocrine tumors that originate from the chromaffin cells of the sympathoadrenal system[1-5]. The incidence of pheochromocytoma in the general population ranges from 0.0002% to 0.0008%[3]. Most pheochromocytomas are located in the adrenal gland due to this location having the largest collection of chromaffin cells[2,3]. Similar to pheochromocytomas, paragangliomas are catecholamine-secreting tumors that arise from extra-adrenal sites along with tumors of the sympathetic nervous system and/or pheochromocytomas (such as the neck, mediastinum, abdomen, and pelvis)[3,6]. Accumulating evidence suggests that the possible mechanism of pheochromocytomas is related with germline mutations in known susceptibility genes, such as NF1 and VHL[7]. In the case of malignant pheochromocytomas, metastases are present in aberrant endocrine tissue without chromaffin cells[3,8]. In general, approximately 2%-26% of pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas are malignant[9]. These metastases are usually located in the bones, liver, lungs, kidneys, and lymph nodes[3,8].

However, malignant pheochromocytomas with cerebral and skull metastasis are even more uncommon. This report describes a case of malignant pheochromocytoma with cerebral and skull metastasis and reviews 16 previously documented cases to gain a better understanding of malignant pheochromocytomas with cerebral and skull metastasis, including the mechanisms of pathogenesis, histopathological and immunohistochemical characteristics, clinical manifestations, radiographic features, and treatments. Furthermore, we also compared malignant pheochromocytoma and meningioma. This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College (B-2020-222).

A 60-year-old man was admitted with a progressive headache and enlarging scalp mass.

The patient’s symptoms started 3 mo ago with a progressive headache and enlarging scalp mass.

The patient’s family reported that he had a history of left adrenal pheochromocytoma, which presented as paroxysmal hypertension and was finally surgically removed at another hospital 5 years prior. The patient also had a 15-year history of gout.

No pertinent family history was identified, including von Hippel-Lindau syndrome, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2, and neurofibromatosis type 1.

The blood pressure was 138/86 mmHg, and the heart rate was 83 beats per minute. The neurological and physical examinations revealed a left temporal scalp mass (6.0 cm × 4.0 cm × 2.0 cm), which was hard and fixed. Other physical findings were unremarkable.

Routine laboratory tests and preoperative hemodynamic and cardiovascular assessments were ordered. The 24-h urinary vanillylmandelic acid (VMA) and metanephrine levels were within normal limits.

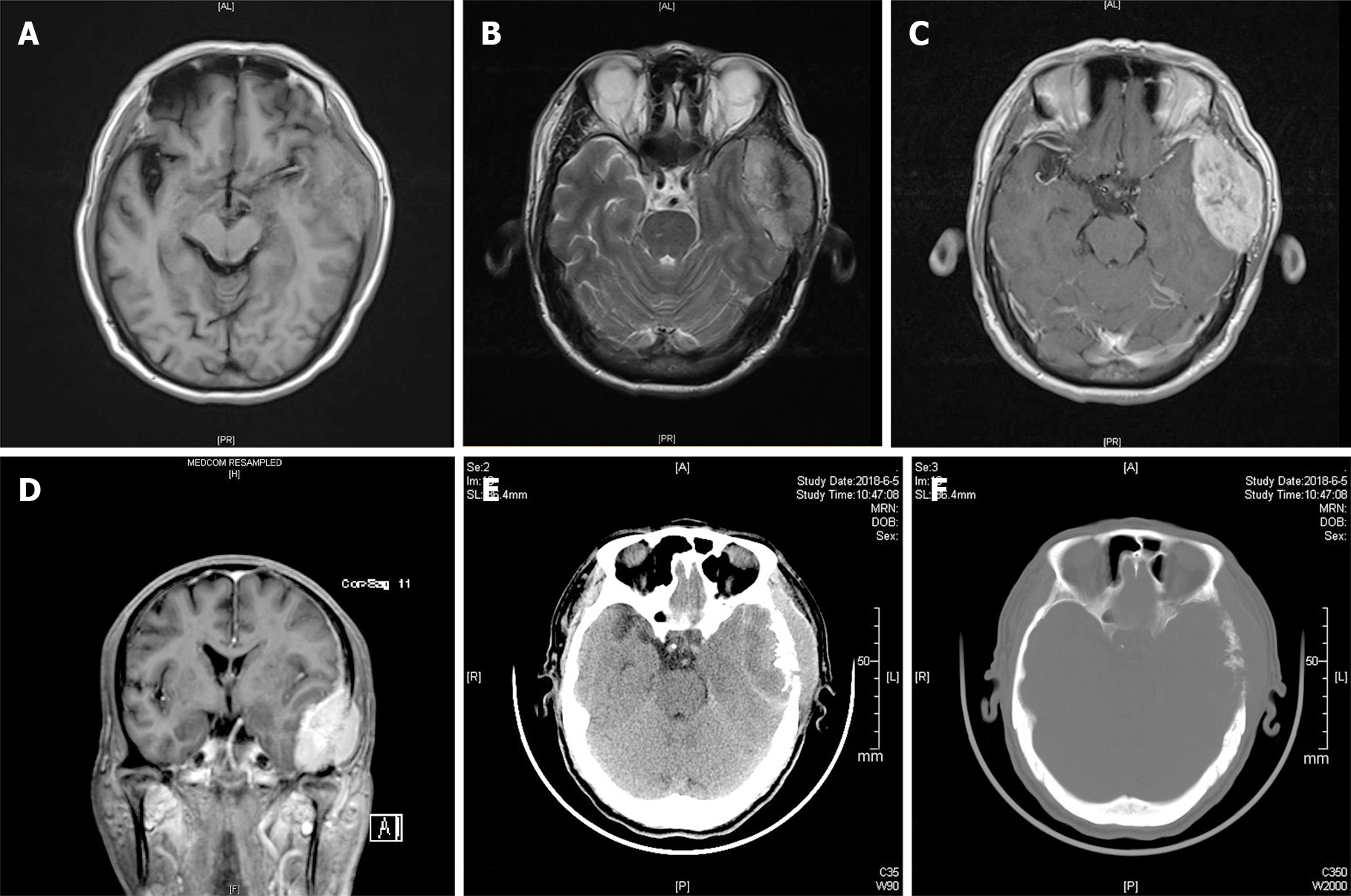

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a biconvex-shaped epidural mass (6.0 cm × 4.0 cm × 3.4 cm) that compressed the left temporal lobe with extracranial and intracranial extension (Figure 1A-D). The mass showed mixed hypo- and hyperintensity on T1-weighted imaging (T1WI) and T2-weighted imaging (T2WI). After gadolinium injection, the homogeneous enhancement of a well-defined lesion with a dural tail sign was observed. Cranial computed tomography (CT) demonstrated multiple lytic lesions in the left temporal bone (Figure 1E and F). The abdominal CT findings were unremarkable, with adrenal lesions. Based on the above findings, our differential diagnosis of this mass lesion included malignant meningioma, skull neoplasm, and even rare malignant pheochromocytoma.

Malignant pheochromocytoma with cerebral and skull metastasis.

The risk of surgical intervention and general anesthesia was high because of the size and abundant blood supply of the tumor. In consultation with the anesthesiologist, adequate preoperative preparations were proposed: Standard blood pressure control (below 160/90 mmHg) and no S-T segment changes or T-wave inversions on electrocardiography. Adequate red blood cells and frozen plasma preparations were also recommended.

The patient underwent a left temporal craniotomy for resection of the temporal tumor. After making an incision in the skin, we found that the tumor had invaded the musculi temporalis. The mass was tightly attached to and infiltrating the underlying bone. Bony decompression (approximately 7 cm × 7 cm) was achieved to completely resect the lesion. After decompression, tumor tissue was found in the epidural space with a blood supply from the underlying dura. Direct tumor manipulation and coagulation and debulking of the supplying blood vessels resulted in significant alterations in blood pressure (70-230/40-110 mmHg). Four units of red blood cells and 400 mL of fresh-frozen plasma were transfused to counteract the blood loss during the operation. The tumor and surrounding dura were completely resected, and no remaining mass was seen in the subdural space. Then, dural grafting was performed with artificial dura. Finally, the outer layers were sutured step-by-step to achieve anatomical reduction. After surgery, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit and placed under close surveillance.

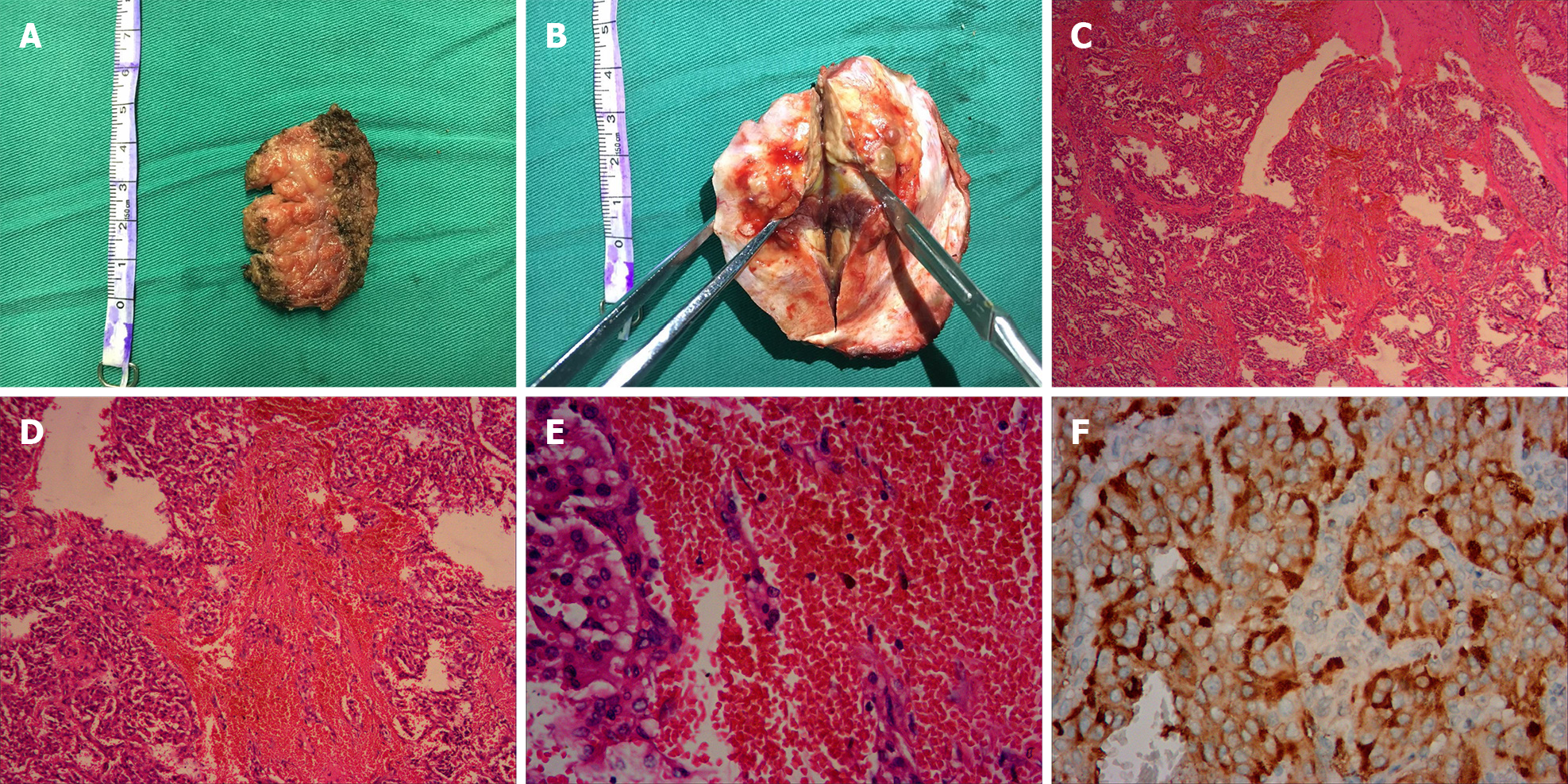

Histopathological analysis led to identification of the mass as malignant pheochromocytoma. Grossly, the surgical specimen was separated into the extracranial part (the musculi temporalis) and the intracranial part (the epidural mass with adhered temporal bone) (Figure 2A and B). Both of these parts were grayish-yellow in color on the cut section. Microscopically, the specimens revealed nested and trabecular arrangements of neoplastic cells surrounded by a labyrinth of capillaries. Granular cytoplasm and round-to-oval nuclei with prominent nucleoli were noted in the neoplastic cells. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed strong, diffuse immunoreactivity for vimentin, Syn, and CgA but negative nuclear and cytoplasmic immunoreactivity for S-100, EMA, and CD10. The P53 labeling index was approximately 1%, while the Ki-67 labeling index was 20% (Figure 2C-F).

Neither fluctuating blood pressure nor cardiac dysfunction parameters were noted in the postoperative course. One week after the operation, the patient’s headache was alleviated. He did not receive chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or targeted therapy.

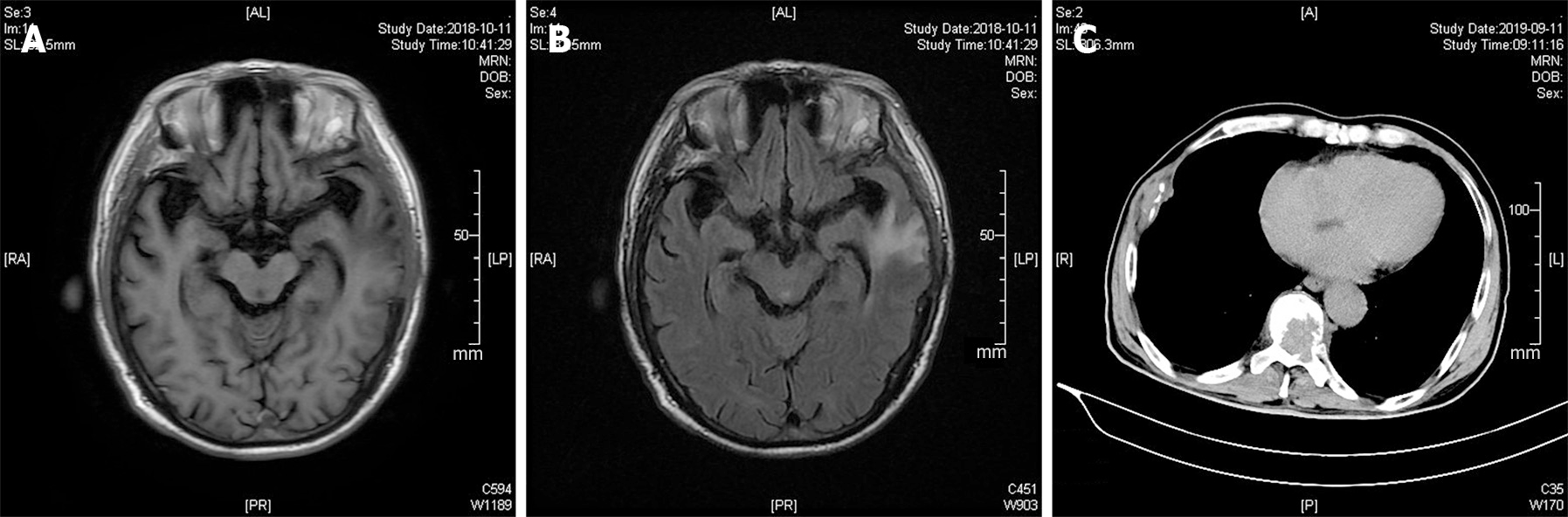

Based on the postoperative 3-mo clinical follow-up, the patient had a favorable outcome, reporting that symptoms were diminished, with normalized blood pressure and catecholamine values and no relapse of the mass on follow-up cranial MRI examinations (Figure 3A and B). However, metastatic pheochromocytoma lesions were found on the right 6th rib and the 6th to 9th thoracic vertebrae on a 1-year clinical follow-up CT scan (Figure 3C).

Malignant pheochromocytomas with cerebral and skull metastasis have preoperative clinical manifestations that vary among patients. According to previous studies, headache, vomiting, and cognitive deterioration are the most frequent symptoms in these patients and are related to the mass effect on the brain parenchyma. Another important symptom is hypertension (including paroxysmal hypertension), which does coincide well with the features of typical pheochromocytomas because of the excess catecholamine secretion. In contrast to the above symptoms of functioning tumors, nonfunctioning malignant pheochromocytomas with cerebral and skull metastasis are usually clinically silent or just painless scalp masses. Some cases were found due to regular radiographic surveillance[16,23]. Silent clinical manifestations may delay the accurate diagnosis, and some patients may develop symptoms because of the metastatic growth of the tumor, which may make subsequent therapy a challenge[3]. Typically, the diagnosis of pheochromocytomas should be based on the findings of different examinations, including clinical, laboratory, and imaging examinations[3]. Preoperative symptoms might be significant signs of deterioration in those with a previous history of pheochromocytoma. We recommend regular radiographic surveillance for pheochromocytoma patients so that malignant metastatic growth can be detected early.

We considered meningioma as a differential diagnosis of malignant pheochromocytoma because they share comparable complaints, clinical manifestations, and imaging features, as observed in our case. Previous studies have indicated that malignant pheochromocytoma has a strong relationship with meningioma in terms of genetic origin. Pheochromocytoma and meningioma originate from a common embryological tissue — the neural crest[16,17]. The cells of the meninges, the adrenal medulla, and paraganglionic tissue are derived from the neural crest. This feature can be strengthened by evidence of "neurocristopathies" (disorders of the neural crest). For example, pheochromocytoma may exist in von Hippel-Lindau disease, and meningioma may exist in neurofibromatosis type 2. Both of these diseases are “neurocristopathies”. In addition, some previous cases have reported the coexistence of pheochromocytoma and meningioma in the brain[26,27]. Furthermore, Gabriel et al[28] reported a rare case in which a patient with supratentorial meningioma and episodic hypertension associated with excess urinary VMA excretion underwent excision of the tumor. The level of VMA became normal after the operation, and they concluded that meningioma may mimic features of pheochromocytoma. These results reinforce the fact that there are many similarities between pheochromocytoma and meningioma.

Some previous studies have pointed out that pheochromocytoma is very similar to meningioma on chromosomal analysis. Mutations in the long arm of chromosome 22 can be found in some pheochromocytoma and neurofibromatosis type 2 (with meningioma and acoustic neurinoma) patients[16,29,30]. It seems that the loss of heterozygosity on the long arm of chromosome 22 is the most likely candidate locus for the combination of pheochromocytoma and meningioma. However, compared to the comparative genomic hybridization of other types of malignant pheochromocytoma, malignant pheochromocytoma with cerebral metastasis has a special loss at 18q, which is believed to be the key genomic alteration[19].

To our knowledge, two previous cases of malignant pheochromocytoma with skull metastasis have been reported[15,16]. After a review of cases of malignant pheochromocytoma with cerebral metastasis in the literature, we found tumor infiltration of the skull in most of these cases, which also occurred in our case. It is difficult to identify whether the malignant pheochromocytoma metastasizes to the brain or the skull because both are involved in these cases (Table 1). Accordingly, we hypothesized that pheochromocytoma metastasis is restricted to tissues with a common embryological origin. In the study by Jiang et al[31], they illustrated that in the mammalian skull vault, the frontal bones are neural crest-derived and the parietal bones are mesodermal in origin. They also suggested that a layer of neural crest cells forms the meningeal covering of the cerebral hemisphere. This fact can explain why osseous cranial metastasis is also associated with intracranial extension. We believe that the metastasis in our case was restricted to cerebral metastasis because the lesions share a common embryological tissue: The parietal bone and meninges are derived from the neural crest. Pure skull metastasis is rare because the meninges cover almost all of the cerebral hemispheres and are next to the inner layer of the skull bones. Schulte et al[21] reported the first case of cystic central nervous system (CNS) metastasis in the right parietal lobe of a patient with malignant pheochromocytoma, which might be a case of metastasis to the meninges.

| Ref. | Year | Age (yr)/sex | Symptoms and signs | Location | Surgery | Immunohistochemical presentation | Adjuvant treatment | Clinical outcome | Others |

| Spatt et al[10] | 1948 | 51/F | Headaches, falls, poor memory, drowsiness and convulsions | Multiple lesions in peduncles, cerebellum, pons, and cerebrum | Right subtemporal decompression | NR | None | Died 8th day postadmission | NR |

| Melicow et al[11] | 1977 | 61/M | Headaches, convulsions, sweating, palpitation and hypertension | NR | None | NR | None | Died 6th week postadmission | Metastases to liver and carcinoid of ileum |

| Ferrari et al[12] | 1979 | 47/M | Progressive cognitive deterioration | Multiple lesions in frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes and cerebellum | None | NR | None | Died 22th day postadmission | NR |

| Grabel et al[13] | 1990 | 43/F | Painless scalp mass | Left parietal lesion | Surgical resection | Chromogranin and neuro-specific enolase and negative for prekeratin | Preoperative chemotherapy | Relieved | NR |

| Mornex et al[14] | 1992 | 49/M | NR | NR | NR | NR | None | Died after 8 yr | Lung, lymph node metastases |

| Gentile et al[15] | 2001 | 31/F | Partial motor crisis | Right frontal lesion | Surgical resection | Neuron-specific enolase, S100 protein and chromogranin; negative for anti-calcitonin | None | No relapse of disease in 4-yr follow-up | MEN type 2a |

| Liel et al[16] | 2002 | 47/M | Radiographic surveillance | Right frontotemporal | Surgical resection | Chromogranin, negative for progesterone receptors and epithelial membrane antigen | Postoperative MIBG therapy | Relieved | Coexistence of recurrent meningioma in the left hemisphere |

| Mercuri et al[17] | 2005 | 46/F | Headaches, vomiting, hypertension | Right temporoparietal extra-axial lesion with inner table skull infiltration. Epidural and subdural | Surgical resection | Neuron-specific enolase, chromogranin A, synaptophysin | None | No relapse of disease in 6-yr follow-up | First primary meningeal pheochromocytoma |

| Kowalska et al[18] | 2009 | 60/F | Hypertension | Left frontal and parietal | Surgical resection | NR | Brain radiotherapy | Relapse in the left front cerebral lobe and right cerebellar hemisphere | Coexistence of left temporal meningioma |

| Schaefer et al[19] | 2010 | 53/M | Headaches, cognitive impairment, visual loss and shortness of breath | Left occipital | Surgical resection | Neuron specific enlase and chromogranin A, negative for keratin, somatostatin, and S-100 | Preoperative chemotherapy and postoperative radiotherapy | Relieved | Differing from the primary PCC only by loss at 18q on CGH analysis |

| Kharlip et al[20] | 2010 | 23/F | Altered mental status | Left occipital, left parietal, and right frontal lobes | None | NR | Chemotherapy and radiotherapy | Relieved from neurologic symptoms but died 8 months later | NR |

| Schulte et al[21] | 2012 | 73/M | Loss of cognitive function, a homonymous hemianopsia and left sided dysmetria | Right parietal lobe | Surgical resection | NR | Adjuvant whole brain radiotherapy | Relieved | First description of a cystic CNS metastasis |

| Miyahara et al[22] | 2017 | 58/M | Headache, right hemiparesis, aphasia, and dysarthria | Left parietal lobe | Surgical resection | positive for chromagranin A, synaptophysin, and S100 | Preoperative Stereotactic radiosurgery | No recurrence for 1 yr | NR |

| Boettcher et al[23] | 2018 | 24/M | Radiographic surveillance | Right posterior parietal, epidural lesion | Surgical resection | Chromogranin, synaptophysin | None | Died several weeks later | SDHB mutation |

| Cho et al[24] | 2018 | 52/M | Headache, dizziness and motor aphasia | Multiple (more than 10) masses in the bilateral cerebral hemisphere and right pons | Surgical resection | Synaptophysin, S100 | Radiotherapy | Died due to progressed intraabdominal cancer | First report in South Korea |

| Kammoun et al[25] | 2019 | 29/F | Headache, vomiting, hypertension | Extradural lesion attached to the tentorium | Surgical resection | Chromogranin, synaptophysin, NSE | Postoperative whole brain radiotherapy | Death 1month after second surgery. No other metastases found | NR |

| Presenting case | 2020 | 60/M | headache and enlarging scalp mass | Left temporal | Surgical resection | Vimentin, Syn and CgA, negative for S-100, EMA and CD10 | None | No relapse of cranial mass | First report in China |

Malignant cerebral pheochromocytoma and meningioma have similar clinical manifestations. As the course and treatment of these diseases can vary, it is important to make an accurate diagnosis as soon as possible. It might be difficult to make an accurate diagnosis on CT or even T1WI and T2WI. However, MRI spectroscopy (MRS) may provide some important clues for making a differential diagnosis of malignant cerebral pheochromocytoma and meningioma. Meningioma often shows a high alanine and methionine signal on MRS, while a high lipid signal suggests meningeal metastasis[25]. Despite the diagnostic utility of MRS, we place special emphasis on the importance of histopathological examination to make an accurate diagnosis.

Surgery: According to the literature review, 12 of 17 patients underwent surgical resection for the treatment of malignant pheochromocytoma with cerebral and skull metastasis. Decompressive surgery was performed in only one patient for relief of the increased intracranial pressure (Table 1). Good clinical outcomes were found in 9 of 12 patients who underwent surgical resection on follow-up. It seems that surgical resection is the primary curative treatment for those patients[3,32-34]. Most metastatic cerebral and skull lesions of malignant pheochromocytoma are superficial to the cerebral hemispheres and easier to remove than tumors in deep parts of the central nervous system. First, complete surgical resection can reduce anatomical complications, such as headaches due to mass effects and cerebral edema[3,32,34]. Second, removal of the tumor can reduce or even abolish excess catecholamine secretion such that the normalization of blood pressure and relief of hormonal manifestations can be achieved[3,32,34]. Third, the opportunity for distant metastasis can be reduced[34]. Last but not least, surgical resection reduces the tumor burden and is beneficial for subsequent radiotherapy because fewer doses of irradiation are needed, which thus reduced the potential for complications of radiation (i.e., bone marrow suppression).

Adequate preoperative management is key to successful surgical resection. Consistent with benign pheochromocytoma, in malignant pheochromocytoma, patients need to achieve good control of hypertension using alpha- and beta-adrenergic blockers. In addition, an appropriate fluid and electrolyte balance is needed[3,32]. The introduction of opioids, antiemetics, neuromuscular blockage, or sympathomimetics and tumor manipulation could lead to a massive intraoperative outpouring of catecholamine, accompanied by fluctuating blood pressure and arrhythmia[34]. Endovascular embolization treatment may be beneficial for surgical resection[22]. It might reduce the blood loss and excess release of catecholamine during the operation. These adequate preoperative managements have a good impact on the process of anesthesia and surgery.

Radiotherapy: Based on our review of case reports on PubMed, 7 of 17 patients underwent radiotherapy or stereotactic radiosurgery[14,18-22,24,25]. The question of whether radiotherapy is beneficial to patients is still open. Kharlip et al[20] reported success in a case in which the cerebral metastasis was nearly eliminated by radiotherapy, and the patient remained free of neurological symptoms without surgery. They suggested that radiotherapy at a dose of 3500 cGy to 4000 cGy should be a treatment option recommended for patients with cerebral metastatic lesions of pheochromocytoma. In the case presented by Cho et al[24], postoperative radiotherapy partially decreased the size of multiple metastatic cerebral lesions on follow-up MRI[24]. Contrary to these two cases, radiotherapy and stereotactic radiosurgery showed poor effects in some other cases[22,25]. 131I-MIBG therapy has been mentioned in two cases as a palliative treatment for metastatic cerebral pheochromocytoma[21,26]. Further studies are needed to determine the efficacy of external irradiation in cerebral metastatic patients.

Chemotherapy: Chemotherapy is considered a choice for malignant pheochromocytoma patients who are not suitable for surgery. The cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and dacarbazine regimen is usually used for neuroblastoma patients but is also used in malignant pheochromocytoma patients because neuroblastoma and pheo-chromocytoma share a common embryological tissue—the neural crest[3,34]. Only 3 of 17 patients had received adjuvant chemotherapy[13,19,20]. There is still a lack of systematic studies evaluating the value of chemotherapy because of the rarity of this pathology.

Malignant pheochromocytoma with cerebral and skull metastasis is extremely rare. It is noteworthy that malignant cerebral pheochromocytoma shares similar clinical manifestations with meningioma because both originate from a common embryological tissue—the neural crest. The different features on MRS and histopathological examination might help to make an accurate diagnosis. Although radiotherapy was effective in two cases, the summary of 17 cases indicates that surgery is the first treatment choice for malignant cerebral pheochromocytoma. Further studies are needed to gain better knowledge on the origin and treatment of malignant cerebral pheochromocytoma.

We thank the participant of this study and all the staff who participated the clinical management of the patient.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Neurosciences

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Lu JW S-Editor: Liu M L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Li X

| 1. | Ayala-Ramirez M, Palmer JL, Hofmann MC, de la Cruz M, Moon BS, Waguespack SG, Habra MA, Jimenez C. Bone metastases and skeletal-related events in patients with malignant pheochromocytoma and sympathetic paraganglioma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:1492-1497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Roman-Gonzalez A, Jimenez C. Malignant pheochromocytoma-paraganglioma: pathogenesis, TNM staging, and current clinical trials. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2017;24:174-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Harari A, Inabnet WB 3rd. Malignant pheochromocytoma: a review. Am J Surg. 2011;201:700-708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Eisenhofer G, Bornstein SR, Brouwers FM, Cheung NK, Dahia PL, de Krijger RR, Giordano TJ, Greene LA, Goldstein DS, Lehnert H, Manger WM, Maris JM, Neumann HP, Pacak K, Shulkin BL, Smith DI, Tischler AS, Young WF Jr. Malignant pheochromocytoma: current status and initiatives for future progress. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2004;11:423-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lenders JW, Duh QY, Eisenhofer G, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP, Grebe SK, Murad MH, Naruse M, Pacak K, Young WF Jr; Endocrine Society. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:1915-1942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1592] [Cited by in RCA: 1724] [Article Influence: 156.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zhang L, Li F, Zhang Y, Zhu S. A rare paraganglioma with skull and brain metastasis. J Clin Neurosci. 2010;17:644-646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fishbein L. Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma: Genetics, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2016;30:135-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tan M, Camargo CA, Mojtahed A, Mihm F. Malignant pheochromocytoma presenting as incapacitating bony pain. Pain Pract. 2012;12:286-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dhir M, Li W, Hogg ME, Bartlett DL, Carty SE, McCoy KL, Challinor SM, Yip L. Clinical Predictors of Malignancy in Patients with Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:3624-3630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | SPATT SD, GRAYZEL DM. Pneochromocytoma of the adrenal medulla; a clinicopathological study of five cases. Am J Med Sci. 1948;216:39-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Melicow MM. One hundred cases of pheochromocytoma (107 tumors) at the Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center, 1926-1976: a clinicopathological analysis. Cancer. 1977;40:1987-2004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ferrari G, Togni R, Pizzedaz C, Aldovini D. Cerebral metastases in pheochromocytoma. Pathologica. 1979;71:703-710. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Grabel JC, Gottesman RI, Moore F, Averbuch S, Zappulla R. Pheochromocytoma presenting as a skull metastasis with massive extracranial and intracranial extension. Neurosurgery. 1990;27:134-6; discussion 136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mornex R, Badet C, Peyrin L. Malignant pheochromocytoma: a series of 14 cases observed between 1966 and 1990. J Endocrinol Invest. 1992;15:643-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gentile S, Rainero I, Savi L, Rivoiro C, Pinessi L. Brain metastasis from pheochromocytoma in a patient with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A. Panminerva Med. 2001;43:305-306. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Liel Y, Zucker G, Lantsberg S, Argov S, Zirkin HJ. Malignant pheochromocytoma simulating meningioma: coexistence of recurrent meningioma and metastatic pheochromocytoma in the base of the skull. Isr Med Assoc J. 2002;4:829-831. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Mercuri S, Gazzeri R, Galarza M, Esposito S, Giordano M. Primary meningeal pheochromocytoma: case report. J Neurooncol. 2005;73:169-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kowalska A, Liziskolus K. Malignant pheochromocytoma with brain metastases and coexisting meningioma: case report. Endocrine. 2009;20:316. |

| 19. | Schaefer IM, Martinez R, Enders C, Loertzer H, Brück W, Rohde V, Füzesi L, Gutenberg A. Molecular cytogenetics of malignant pheochromocytoma with cerebral metastasis. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2010;200:194-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kharlip J, Teytelboym O, Kleinberg L, Purtell M, Basaria S. Successful radiation therapy for cerebral metastatic lesions from a pheochromocytoma. Endocr Pract. 2010;16:334-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Schulte DM, Faust M, Schmidt M, Ruge MI, Grau S, Blau T, Kocher M, Krone W, Laudes M. Novel therapeutic approaches to CNS metastases in malignant phaeochromocytomas - case report of the first patient with a large cystic CNS lesion. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2012;77:332-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Miyahara M, Okamoto K, Noda R, Inoue M, Tanabe A, Hara T. Cerebral metastasis of malignant pheochromocytoma 28 years after of disease onset. Interdiscipl Neurosurg. 2017;10:130-134. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Boettcher LB, Abou-Al-Shaar H, Ravindra VM, Horn J, Palmer CA, Menacho ST. Intracranial Epidural Metastases of Adrenal Pheochromocytoma: A Rare Entity. World Neurosurg. 2018;114:235-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Cho YS, Ryu HJ, Kim SH, Kang SG. Pheochromocytoma with Brain Metastasis: A Extremely Rare Case in Worldwide. Brain Tumor Res Treat. 2018;6:101-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kammoun B, Belmabrouk H, Kolsi F, Kammoun O, Kallel R, Ammar M, Kallel M, Mseddi MA, Boudawara MZ. Brain Metastasis of Pheochromocytoma: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Challenge. World Neurosurg. 2019;130:391-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Tisherman SE, Tisherman BG, Tisherman SA, Dunmire S, Levey GS, Mulvihill JJ. Three-decade investigation of familial pheochromocytoma. An allele of von Hippel-Lindau disease? Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:2550-2556. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Tanaka S, Okazaki M, Egusa G, Takai S, Mochizuki H, Yamane K, Hara H, Yamakido M. A case of pheochromocytoma associated with meningioma. J Intern Med. 1991;229:371-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Gabriel R, Harrison BD. Meningioma mimicking features of a phaeochromocytoma. Br Med J. 1974;2:312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Mérel P, Hoang-Xuan K, Sanson M, Moreau-Aubry A, Bijlsma EK, Lazaro C, Moisan JP, Resche F, Nishisho I, Estivill X. Predominant occurrence of somatic mutations of the NF2 gene in meningiomas and schwannomas. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1995;13:211-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Tanaka N, Nishisho I, Yamamoto M, Miya A, Shin E, Karakawa K, Fujita S, Kobayashi T, Rouleau GA, Mori T. Loss of heterozygosity on the long arm of chromosome 22 in pheochromocytoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1992;5:399-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Jiang X, Iseki S, Maxson RE, Sucov HM, Morriss-Kay GM. Tissue origins and interactions in the mammalian skull vault. Dev Biol. 2002;241:106-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 549] [Cited by in RCA: 566] [Article Influence: 24.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Jimenez C, Rohren E, Habra MA, Rich T, Jimenez P, Ayala-Ramirez M, Baudin E. Current and future treatments for malignant pheochromocytoma and sympathetic paraganglioma. Curr Oncol Rep. 2013;15:356-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Lenders JW, Eisenhofer G, Mannelli M, Pacak K. Phaeochromocytoma. Lancet. 2005;366:665-675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1154] [Cited by in RCA: 1136] [Article Influence: 56.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Jimenez P, Tatsui C, Jessop A, Thosani S, Jimenez C. Treatment for Malignant Pheochromocytomas and Paragangliomas: 5 Years of Progress. Curr Oncol Rep. 2017;19:83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |