Published online Jan 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i1.91

Peer-review started: June 15, 2020

First decision: September 13, 2020

Revised: October 10, 2020

Accepted: November 13, 2020

Article in press: November 13, 2020

Published online: January 6, 2021

Processing time: 200 Days and 5.5 Hours

Separation of the pubic symphysis can occur during the peripartum period. Relaxin (RLX) is a hormone primarily secreted by the corpus luteum that can mediate hemodynamic changes during pregnancy as well as loosen the pelvic ligaments. However, it is unknown whether RLX is associated with peripartum pubic symphysis separation and if the association is affected by other factors.

To study the association between RLX and peripartum pubic symphysis separation and evaluate other factors that might affect this association.

We performed a cross-sectional study of pregnant women between April 2019 and January 2020. Baseline demographic characteristics, including gestational age, weight, neonatal weight, delivery mode and duration of the first and second stages of labor, were recorded. The clinical symptoms were used as a screening index during pregnancy, and the patients with pubic symphysis and inguinal pain were examined by color Doppler ultrasonography to determine whether there was pubic symphysis separation. Serum RLX concentrations were evaluated 1 d after delivery using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and pubic symphysis separation was diagnosed based on postpartum X-ray examination. We used an independent-sample t test to analyze the association between serum RLX levels and peripartum pubic symphysis separation. Multivariate regression analysis was used to evaluate whether the association between RLX and peripartum pubic symphysis separation was confounded by other factors, and the association between RLX and the severity of pubic symphysis separation was also assessed. We used Pearson correlation analysis to determine the factors related to RLX levels as well as the correlation between the degree of pubic symphysis separation and activities of daily living (ADL) and pain.

A total of 54 women were enrolled in the study, with 15 exhibiting (observational group) and 39 not exhibiting (control group) peripartum pubic symphysis separation. There were no statistically significant differences in terms of maternal age, gestational age, pre-pregnancy weight, weight gain during pregnancy, delivery modes, or duration of the first or second stages of labor between the 2 groups. We did, however, note a statistically significant difference in serum RLX concentrations and neonatal weight between the observational and control groups (122.3 ± 0.7 µg/mL vs 170.4 ± 42.3 µg/mL, P < 0.05; 3676.000 ± 521.725 g vs 3379.487 ± 402.420 g, P < 0.05, respectively). Multivariate regression analyses showed that serum RLX level [odds ratio (OR): 1.022) and neonatal weight (OR: 1.002) were associated with pubic symphysis separation peripartum. The degree of separation of the pubic symphysis was negatively correlated with ADL and positively correlated with pain. There was no statistically significant association between serum RLX levels and the severity of pubic symphysis separation after adjusting for confounding factors.

Serum RLX levels and neonatal weight were associated with the occurrence, but not the severity, of peripartum pubic symphysis separation.

Core Tip: Peripartum separation of the pubic symphysis is not a frequent pregnancy complication, but it can cause chronic pelvic pain and difficult ambulation. Furthermore, it limits activities of daily living (ADL). We performed a cross-sectional study and identified an association between postpartum serum relaxin (RLX) levels and neonatal weight with peripartum separation of the pubic symphysis. The degree of separation of the pubic symphysis was positively correlated with the degree of pain and was negatively correlated with ADL. Serum RLX levels and neonatal weight may be used to identify women at a high risk of pubic symphysis separation peripartum.

- Citation: Wang Y, Li YQ, Tian MR, Wang N, Zheng ZC. Role of relaxin in diastasis of the pubic symphysis peripartum. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(1): 91-101

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i1/91.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i1.91

Separation of the pubic symphysis refers to dislocation of the pubic fibrocartilages on both sides of the pelvis due to pregnancy or external forces. Soft-tissue injuries, such as the widening of the pubic symphysis or dislocation of the pubic symphysis, with local pain and difficulty in lifting lower limbs, often occur in pregnant and postpartum women[1]. A pubic symphysis gap wider than 10 mm combined with clinical symptoms typically engenders a diagnosis of perinatal pubic symphysis diastasis (PSD)[2]. Since the first case published by Reis et al[3] in 1932, the incidence reported in China and elsewhere has been approximately 1/300 to 1/30000[4-8]. Kubitz et al[5] reported an incidence of 1/300 (the highest in the group of study reports we evaluated), and Kane et al[4] reported an incidence of 1/30000 (the lowest). Pregnancy and childbirth are different in each country and region of the world, as is the incidence of PSD. Since the changes to China’s fertility strategy in 2016 to a 2-child policy, excitement regarding reproductive family planning in China has shown a resurgence, although research on patients with pubic symphysis separation is still quite rare. The lack of understanding or misdiagnosis of the disease is also one of the reasons for the great disparity in the incidence of the disease depicted in various studies. Although perinatal separation of the pubic symphysis is not a common clinical complication, it seriously affects the physical and mental wellbeing and quality of life of parturients. In fact, some patients even revert to the previous level of pubic symphysis separation due to a lack of knowledge, diagnosis, or timely treatment, resulting in chronic injury.

The cause of postpartum pubic symphysis separation is unclear[9]. Bathgate et al[10] demonstrated that the level of relaxin (RLX) in early pregnancy was increased, but its role in promoting cervical maturation and delivery remains unclear. Yoo et al[11] proposed that RLX was not the primary cause of pubic symphysis separation, although multiple pregnancies result in a higher risk for its development. Other investigators have indicated that factors associated with PSD might include dystocia, urgent labor, violent midwifery, and fetal factors such as pelvic asymmetry, abnormal presentation and an excessively large fetus. However, all the aforementioned studies were retrospective in nature, without rigorous controls. In addition, most investigators only evaluated a single risk factor, whereas the causes of postpartum PSD may be multifactorial.

A review of the literature in China and elsewhere indicated that imaging methods related to postpartum pubic symphysis primarily included X-ray, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography, and ultrasonographic examination. Commonly used pelvic X-ray can accurately show the width of the pubic symphysis at different angles, but it is generally not applicable when there are symptoms related to pregnancy; thus, color ultrasound and MRI have become the modalities of choice. MRI requires a lengthy time for examination and is expensive, but it exhibits more advantages in elucidating soft-tissue injuries (especially the sacroiliac joint and peri-pubic symphysis ligament complex) and subchondral bone edema[12]. Compared with MRI examination, color ultrasonography provides a safe, simple, economical, and effective examination method[13]. Therefore, in the present study, we used color ultrasound during pregnancy, and X-ray was used after delivery.

In 1926, Hisaw et al[14] injected the serum from pregnant guinea pigs subcutaneously into non-pregnant guinea pigs for the first time, which demonstrated a relaxing effect on the pubic ligaments of non-pregnant animals. In 1930, Fevold et al[15] extracted the substance from the corpus luteum (CL) of sows and named it “relaxin”. We now know that RLX is not only expressed in the reproductive system, but is also found in different tissues and organs including the liver, kidney, heart, and brain. RLX participates in complex and diverse physiologic and pathologic processes and targets multiple organs; it is a multi-potential hormone with broad implications for both basic science and applied medicine[16]. RLX is encoded by the H2 gene and is synthesized by the CL and secreted into the blood circulation. Although RLX is primarily secreted by the CL in women, it is also secreted by endometrial stromal cells and glandular epithelial cells. Deciduomata, placenta, and fetal membranes secrete RLX as an autocrine or paracrine hormone. RLX is thus of critical importance in maintaining normal pregnancy and delivery. In addition, RLX participates in a variety of physiologic processes including promoting breast and vaginal growth, endometrial development and decidua formation, relaxing uterine smooth muscle, stimulating cervical growth and reconstruction, relaxing the pubic symphysis, and ensuring the smooth progress of delivery[17]. However, whether the level of RLX in pregnant women is one of the factors affecting separation of the pubic symphysis has not yet been determined.

We therefore designed the present study to evaluate the risk factors for pubic symphysis separation, and specifically investigated whether a high level of RLX was associated with pubic symphysis separation.

We performed a cross-sectional study and included pregnant women who delivered at our hospital between April 2019 and January 2020. Our inclusion criteria were pregnant women who agreed to a blood test for RLX levels and agreed to a postpartum pelvic X-ray to evaluate PSD. Clinical symptoms were used as the screening index during pregnancy. Patients with pubic symphysis and inguinal pain were examined by color Doppler ultrasonography to determine whether there was pubic symphysis separation, and by pelvic X-ray examination after delivery to assess the degree of separation. None of the patients had a history of separation of the pubic symphysis, and patients with severe liver, renal, or cardiac diseases or other underlying conditions were excluded.

We recorded general information regarding the puerpera, including maternal age, pre-pregnancy weight, weight gain, duration of the first and second stages of labor, and neonatal weight. We documented the distance of PSD by pelvic X-ray. Patients with pubic symphysis separation during pregnancy were initially screened by clinical manifestations such as pain at the pubic symphysis, and color Doppler ultrasonography was then performed to determine whether there was pubic symphysis separation.

RLX levels in blood samples collected 1 d after delivery were determined for each study participant. The concentration of serum RLX was determined by an ELISA method as follows: (1) 4 mL of each patient’s blood was taken from the antecubital vein and placed in a test tube without anticoagulant. The serum was separated by centrifugation at 1000 r/min for 15 min at 4°C, and the separated serum was immediately stored at -80°C for testing; and (2) The level of serum RLX was then measured with an ELISA kit using plate wells coated with human RLX antibody (Redd Biological Preparation Co., United States).

Fifteen parturients had PSD and 39 parturients did not have PSD. Of the 15 parturients with diastasis, 8 showed pubic symphysis separation as confirmed by color Doppler ultrasonography, 5 underwent cesarean sections, 3 had spontaneous deliveries, and 7 exhibited pubic symphysis separation after delivery. Of these 15 patients, 13 showed pubic symphysis separation with a gap > 1 cm, and 2 patients with a superior and inferior pubic symphysis dislocation > 1 cm with a separation distance < 1 cm, including 5 patients who received three-dimensional (3D) adjustment of the pelvis under suspension. Of the parturients without symphysis pubis separation, 19 underwent cesarean section and 20 delivered spontaneously.

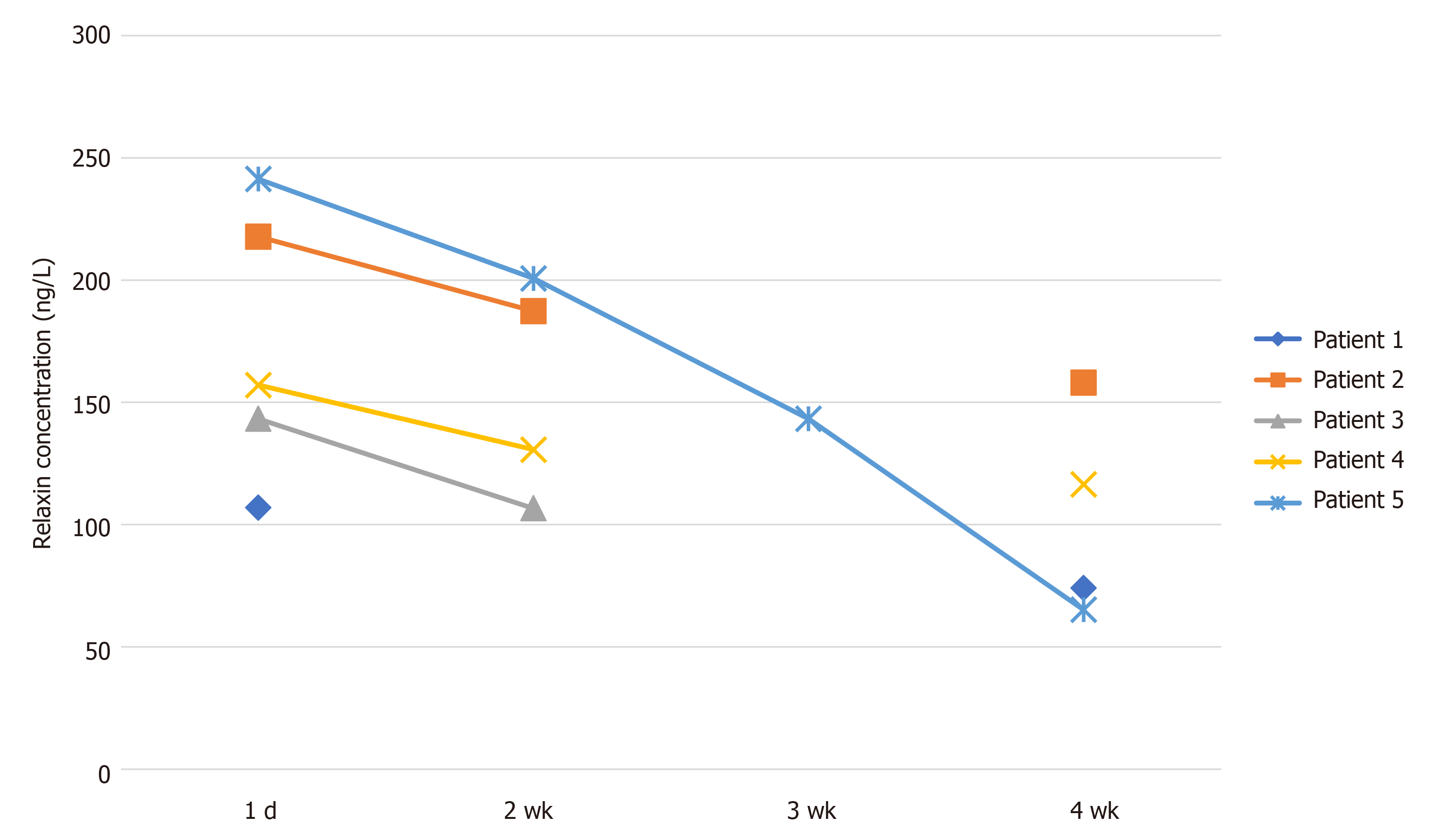

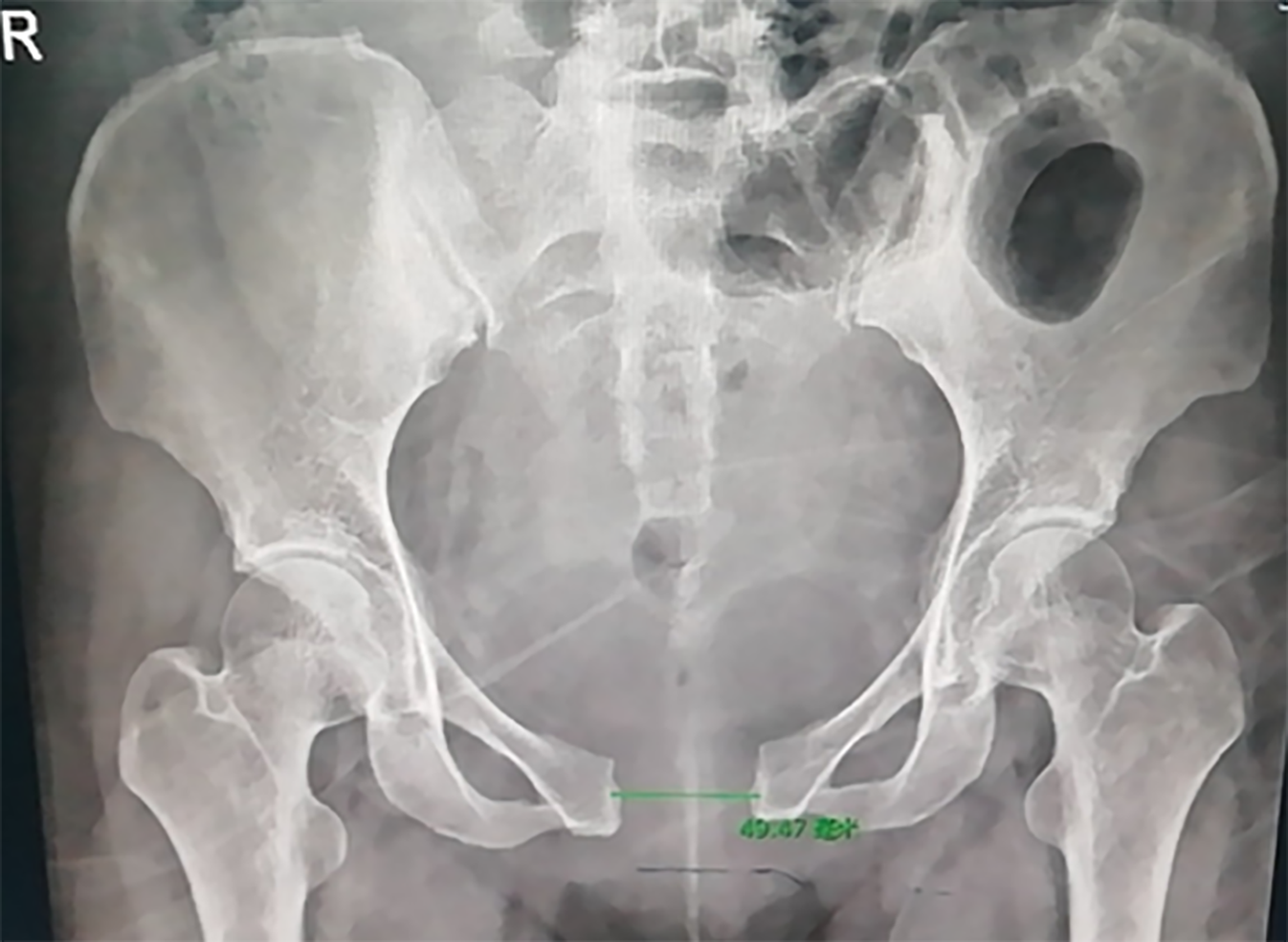

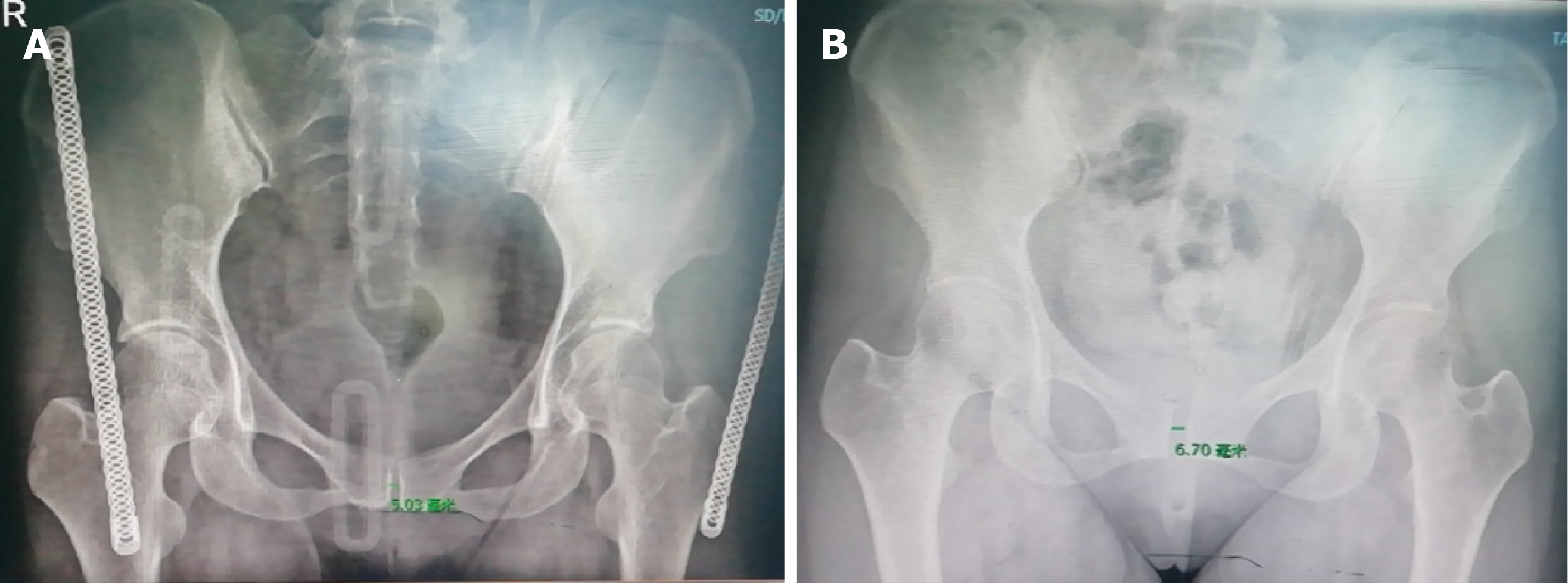

We collected postpartum blood samples from 5 patients to detect the levels of RLX relative to the voluntary condition of the patients (Figure 1). After 6 wk of fixation, the clinical symptoms in 4 patients disappeared and the pelvic band was removed. In one patient with a 4.185-cm separation, the clinical symptoms disappeared, and the pelvic band was removed after 8 wk of fixation. Figure 2 shows the X-ray film of the pelvis before separation and reduction of the pubic symphysis in a postpartum woman who had a 4.185-cm gap. Figure 3 shows a pelvic X-ray after reduction of the pubic symphysis and removal of the pelvic band after 2 wk.

We used SPSS (version 20.0; IBM, United States) for statistical analysis. Continuous data are presented as mean ± SD and categorical data are presented as percentages. An independent sample t test and Chi-squared test were used to compare the 2 groups. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05. Unconditional multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to analyze the potential multiple factors related to pubic symphysis separation. We used multiple linear regression analysis to explore the associations between serum RLX levels as well as other factors with the degrees of pubic symphysis separation. Pearson correlation analysis was used to study the factors related to RLX levels, and to assess any correlations between the degree of separation of the pubic symphysis, activities of daily living (ADL) and pain.

A total of 54 peripartum women were enrolled in our study; 15 had pubic symphysis separation (observational group), and 39 did not have separation (control group). Of the 15 women with separation, 5 underwent cesarean section, 3 delivered spontaneously, and 7 exhibited pubic symphysis separation after delivery. Of these 15 patients, 13 exhibited pubic symphysis separation with a gap > 1 cm, and 2 patients had a superior and inferior pubic symphysis dislocation of > 1 cm, with a separation distance of < 1 cm. Five patients also received 3D adjustment of the suspended pelvis. With regard to the controls without symphysis pubis separation, 19 cases underwent cesarean sections and 20 cases delivered spontaneously. Comparisons between the observational group and the control group are listed in Tables 1 and 2. Except for serum RLX levels and neonatal weight, there were no statistically significant differences in the variables measured between these 2 groups.

| Variables | Control group | Observational group | t | P value |

| Relaxin concentration (µg/mL) | 170.435 ± 42.299 | 122.380 ± 0.729 | 3.245 | 0.002 |

| Weight of baby (g) | 3676.000 ± 521.725 | 3379.487 ± 402.420 | 2.229 | 0.03 |

| Gestational age (wk) | 39.809 ± 0.839 | 39.105 ± 1.258 | 1.998 | 0.051 |

| Age at delivery (yr) | 29.667 ± 4.271 | 30.795 ± 4.964 | −0.776 | 0.441 |

| Pre-pregnancy weight | 75.467 ± 8.269 | 76.731 ± 10.807 | −0.408 | 0.685 |

| Weight gain during pregnancy | 18.643 ± 2.706 | 17.716 ± 4.759 | 0.685 | 0.497 |

| First stage of labor (min) | 359 ± 134.346 | 374.25 ± 122.553 | −0.311 | 0.758 |

| Second stage of labor (min) | 54.70 ± 43.16 | 45.80 ± 39.325 | 0.566 | 0.576 |

For our unconditional, multivariate logistic regression analysis (using the forward-step method), the following were entered into the equation: RLX level, neonatal weight, gestational age, maternal age, age at delivery, weight gain during pregnancy, duration of the first stage of labor, and duration of the second stage of labor. With separation = 1 and no separation = 0, the final variables left in the equation were infant weight and RLX level. The odds ratio (OR) values were 1.002 and 1.022, respectively, suggesting that infant weight and RLX levels were independent risk factors for pubic symphysis separation (Table 3).

| B | Standard error | Wald test quantity | Degrees of freedom | P value | OR | |

| Weight of baby (kg) | 0.002 | 0.001 | 4.107 | 1 | 0.043 | 1.002 |

| Relaxin concentration (µg/mL) | 0.022 | 0.008 | 8.075 | 1 | 0.004 | 1.022 |

| −10.508 | 3.673 | 8.183 | 1 | 0.004 | 0.000 |

There were no significant differences in RLX levels, diastatic gap, neonatal weight, gestational age, age at delivery, pre-pregnancy weight, weight gain during pregnancy, or duration of the first or second stage of labor with pubic symphysis separation during the pregnancy or postpartum periods (Table 4).

| Pregnancy diastasis | Postpartum diastasis | t | P value | |

| Relaxin content (µg/mL) | 162.049 ± 43.178 | 177.774 ± 42.994 | -0.705 | 0.493 |

| Diastatic gap (cm) | 1.285 ± 0.458 | 2.168 ± 1.151 | -1.896 | 0.08 |

| Weight of baby (g) | 3807.143 ± 440.519 | 3561.250 ± 588.058 | 0.905 | 0.382 |

| Gestational age (wk) | 39.754 ± 0.837 | 39.858 ± 0.896 | -0.229 | 0.822 |

| Age at delivery (yr) | 30 ± 3.559 | 29.375 ± 5.041 | 0.273 | 0.789 |

| Pre-pregnancy weight | 78.500 ± 8.646 | 72.813 ± 7.445 | 1.370 | 0.194 |

| Weight gain during pregnancy | 18.5 ± 2.345 | 18.75 ± 3.105 | -0.165 | 0.872 |

| First stage of labor (min) | 282.50 ± 173.241 | 378.13 ± 129.723 | -0.890 | 0.400 |

| Second stage of labor (min) | 83.50 ± 94.045 | 47.50 ± 28.909 | 1.063 | 0.319 |

Taking the degree of separation as the dependent variable, multivariate linear regression analysis was performed. The following independent variables were entered into the equation: Gestational age, age at delivery, pre-pregnancy weight, neonatal weight, durations of the first and second stages of labor, and weight gain during pregnancy. We observed no statistical significance following this analysis, even after variable transformation due to the non-normal distribution of most of the independent variables. Thus, there was no obvious correlation between the degree of separation and the factors tested (Table 5).

| Unstandardized coefficient | Standardization coefficient | t | P value | Collinear statistics | |||

| B | Standard error | Beta | Tolerance | Variance inflation factor | |||

| Variables | -8.200 | 29.024 | -0.283 | 0.825 | |||

| Gestational age (wk) | 0.653 | 0.695 | 0.477 | 0.939 | 0.520 | 0.361 | 2.772 |

| Age at delivery (yr) | -0.137 | 0.111 | -0.562 | -1.238 | 0.433 | 0.451 | 2.215 |

| Pre-pregnancy weight | -0.077 | 0.103 | -0.601 | -0.744 | 0.593 | 0.143 | 7.008 |

| Baby weight (kg) | 0.000 | 0.002 | -0.136 | -0.170 | 0.893 | 0.146 | 6.859 |

| First stage of labor (min) | -0.001 | 0.006 | -0.150 | -0.200 | 0.874 | 0.167 | 6.002 |

| Second stage of labor (min) | 0.000 | 0.010 | 0.008 | 0.020 | 0.987 | 0.560 | 1.786 |

| Relaxin content (µg/mL) | 0.013 | 0.014 | 0.494 | 0.928 | 0.524 | 0.327 | 3.056 |

| Weight gain during pregnancy | 0.366 | 0.175 | -0.938 | -2.098 | 0.283 | 0.465 | 2.151 |

Correlation analysis between RLX levels and other factors: We analyzed the correlations between the levels of RLX and other factors in this study, and found no correlations for gestational age, age at delivery, pre-pregnancy weight, neonatal weight, weight gain during pregnancy, or delivery duration (Table 6).

| Gestational age (wk) | Age at delivery (yr) | Pre-pregnancy weight (kg) | Weight gain during pregnancy (kg) | Neonatal weight (g) | Delivery duration | ||

| Relaxin level | Pearson’s correlation coefficient | 0.145 | 0.118 | −0.081 | 0.012 | 0.002 | 0.034 |

| P value | 0.301 | 0.339 | 0.563 | 0.931 | 0.986 | 0.808 |

Analysis of the correlations between the degree of separation and Barthel index and visual analog scale score: Analysis of the correlations between the degree of separation and ADL (Barthel index) and pain (visual analog scale) is shown in Table 7.

| Barthel index | Visual analog scale | ||

| Degree of separation | Pearson’s correlation coefficient | −0.828 | 0.960 |

| P value | 0.000 | 0.000 |

Natural anti-fibrotic substances are present in the body to maintain overall homeostasis; RLX is one of these substances. RLX can inhibit fibroblast proliferation and differentiation by inhibiting pro-fibrotic factors, such as transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) and angiotensin II, and stimulate matrix degradation induced by metalloproteinases. RLX also reduces the degree of scar formation[18]. Unemori et al[19] and Mookerjee et al[20] found that RLX inhibited the differentiation of renal fibroblasts and collagen deposition by inhibiting phosphorylation of Smad2, thus interfering with TGF-β1[21,22]. An increase in RLX levels also causes ligament and tendon injury. Therefore, the higher levels of RLX in pregnant women might exert a stronger anti-fibrotic effect, which would lead to ligament relaxation and damage. The level of RLX is highest in the first 3 mo of pregnancy and in the perinatal period[23], which leads to the relaxation of pelvic ligaments, especially in the latter period. Compression by fetal weight and other forces during labor can then quickly lead to separation of the pubic symphysis.

For the current study, we enrolled 15 parturients with pubic symphysis separation in the observational group and 39 parturients without separation in the control group. An independent-sample t test and unconditional multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that RLX levels and fetal weight were associated with separation of the pubic symphysis. The increased levels of RLX apparently caused relaxation of the peri-pelvic ligaments, with the peri-pubic symphysis ligament only damaged when the fetus was older. We concluded from this that the high level of RLX was the principal cause of the damage we observed, with reports of RLX levels dropping approximately 4 wk after delivery. We therefore cannot ignore the role(s) of RLX in the relaxation of ligaments during pregnancy and delivery as well as in the healing process, to overcome the late separation of the pubic symphysis. Only when the levels of RLX in the puerperal body return to normal can the typical healing process begin. Although RLX levels and newborn weight were associated with pubic symphysis separation, the OR values from the regression analysis were lower. Future studies that entail a larger sample size and longer follow-up period need to be performed in order to confirm our study results.

A diastasis greater than 14 mm usually indicates attendant damage to the sacroiliac joint[24]; this is consistent with our observation that when separation of the pubic symphysis exceeded 14 mm, there was a displacement of the ilium relative to the sacrum. The treatment methods reported in the literature[8,13,15], including bed rest, stents, pelvic belt support, and walking aids, were not adjusted according to the separations observed in patients. The pubic symphysis and the sacroiliac joint allow the sacrum and hip bone to form a complete bone ring, and dislocation of the pubic symphysis must be accompanied by movement of the sacroiliac joint. If we do not correct this in a timely fashion, the dislocated symphysis will heal in the wrong position after 8 wk of fibrous regeneration. The ilium is connected downward toward the lower limbs through the hip joint, and the change in the position of the ilium on both sides causes unequal length of the lower limbs on either side. In order to adjust for this, the body must be compensated through the spine; however, scoliosis will occur when the compensation time is overly long. Patients with separation of the pubic symphysis without systematic treatment at our outpatient clinic exhibited scoliosis 6 mo after delivery (the specific timing of the scoliosis was uncertain). When the diastatic-gap distance or position of the pubic symphysis is abnormal, changes in the abdominal muscles attached to the ilium and pubic symphysis (such as the rectus inferior), thigh adductors (such as the adductor magnus and adductor longus, along with pectoral lymph nodes, gluteus maximus, and gluteus medius), lumbar muscles (such as the psoas major and iliopsoas), and back muscles (such as the erector spinae and latissimus dorsi) can also cause chronic pain in patients with separation of the pubic symphysis. In some patients, we found that the pain was relieved or even disappeared completely after 8 wk; however, new pain symptoms appeared 3 mo later.

There is currently no unified standard for the diagnosis and treatment of perinatal pubic symphysis separation in China or elsewhere. In our study, we found that although the incidence of pubic symphysis separation was not high, the pain and the limitations on ADL greatly affected an individual’s quality of life. To improve the overall health of women, more attention must therefore be given to the possible separation of the pubic symphysis during the perinatal period.

Limitations of our study included a small sample size at a single study center. We also did not study the dynamic changes in serum RLX levels during the peripartum period or uncover a reason for the increase in RLX. Future studies should address these issues.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that serum RLX levels and neonatal weight were associated with peripartum separation of the pubic symphysis. Serum RLX levels, as well as neonatal weight, might therefore be used to identify peripartum women with a high risk for pubic symphysis separation. Pregnant women with low serum RLX levels also might consider prophylactic measures and screens for peripartum pubic symphysis separation. Serum RLX levels and neonatal weight were associated with the occurrence, but not the severity, of peripartum pubic symphysis separation.

Although the incidence of postpartum pubic symphysis separation is not high, the pain and mobility disorders caused by it seriously affect the quality of life of women. However, current research has not elucidated the etiology and treatment of this disease. The purpose of this study was to determine whether increased relaxin (RLX) levels were a risk factor for pubic symphysis separation, and whether other factors were involved.

To study the association between RLX and peripartum pubic symphysis separation, and to evaluate other factors that might affect this association. In the future, we hope to predict the risk of pubic symphysis diastasis by determining RLX levels and controlling the possible factors involved, in order to reduce the incidence of postpartum pubic symphysis separation.

We studied the relationships between RLX levels/other factors and the occurrence of pubic symphysis separation, and determined that maternal RLX levels and neonatal weight were risk factors for symphysis pubis separation. This information can be used to guide clinical judgment on the risk of pubic symphysis separation, and thereby reduce its incidence.

We performed a cross-sectional study on pregnant women between April 2019 and January 2020. Baseline demographic characteristics, including gestational age, weight, neonatal weight, delivery mode and duration of the first and second stages of labor, were recorded, as well as the pubic symphysis separation, maternal capability for daily life activities, and pain scores. Several statistical methods were used to analyze the data. Previous studies did not include as many factors as we have shown herein, and investigators did not conduct comparative studies.

In the present study, it was found that RLX levels and neonatal weight were risk factors for peripartum separation of the pubic symphysis. We wished to determine the possible pathogenic factors leading to symphysis pubis separation; however, the sample size of our study was not large, and further research is needed.

Serum RLX levels and neonatal weight were associated with the occurrence, but not the severity, of peripartum pubic symphysis separation.

In our future studies, we will expand the sample size to further explore the role of RLX levels in peripartum pubic symphysis separation. We will also continue to observe the significant changes in RLX levels in peripartum pubic symphysis separation and subsequent healing.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: De Carolis S S-Editor: Chen XF L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Herren C, Sobottke R, Dadgar A, Ringe MJ, Graf M, Keller K, Eysel P, Mallmann P, Siewe J. Peripartum pubic symphysis separation--Current strategies in diagnosis and therapy and presentation of two cases. Injury. 2015;46:1074-1080. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Shnaekel KL, Magann EF, Ahmadi S. Pubic Symphysis Rupture and Separation During Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2015;70:713-718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Reis RA, Baer JL, Arens RA, Stewart E. Traumatic separation of the symphysis pubis during spontaneous labor. Surg Gynec Obst. 1932;55:336-354. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kane R, Erez S, O'Leary JA. Symptomatic symphyseal separation in pregnancy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1967;124:1032-1036. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kubitz RL, Goodlin RC. Symptomatic separation of the pubic symphysis. South Med J. 1986;79:578-580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Saeed F, Trathen K, Want A, Kucheria R, Kalla S. Pubic symphysis diastasis after an uncomplicated vaginal delivery: A case report. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;35:746-747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ku SJ, Kim SB, Kim JH, Park HR, Kim HJ. Clinical analysis of the perinatal pubic bone separation. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;49:315-321. |

| 8. | Heath T, Gherman RB. Symphyseal separation, sacroiliac joint dislocation and transient lateral femoral cutaneous neuropathy associated with McRoberts' maneuver. A case report. J Reprod Med. 1999;44:902-904. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Snow RE, Neubert AG. Peripartum pubic symphysis separation: a case series and review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1997;52:438-443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bathgate RA, Halls ML, van der Westhuizen ET, Callander GE, Kocan M, Summers RJ. Relaxin family peptides and their receptors. Physiol Rev. 2013;93:405-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 354] [Cited by in RCA: 400] [Article Influence: 33.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yoo JJ, Ha YC, Lee YK, Hong JS, Kang BJ, Koo KH. Incidence and risk factors of symptomatic peripartum diastasis of pubic symphysis. J Korean Med Sci. 2014;29:281-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Valsky DV, Anteby EY, Hiller N, Amsalem H, Yagel S, Hochner-Celnikier D. Postpartum pubic separation associated with prolonged urinary retention following spontaneous delivery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85:1267-1269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Svelato A, Ragusa A, Perino A, Meroni MG. Is x-ray compulsory in pubic symphysis diastasis diagnosis? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2014;93:219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hisaw FL, Zarrow MX. The physiology of relaxin. Vitam Horm. 1950;8:151-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Fevold HL, Hisaw FL, Meyer RK. The relaxative hormone of the corpus luteum: its purification and concentration. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;52:3340-3348. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Cernaro V, Lacquaniti A, Lupica R, Buemi A, Trimboli D, Giorgianni G, Bolignano D, Buemi M. Relaxin: new pathophysiological aspects and pharmacological perspectives for an old protein. Med Res Rev. 2014;34:77-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Anand-Ivell R, Ivell R. Regulation of the reproductive cycle and early pregnancy by relaxin family peptides. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2014;382:472-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Samuel CS, Lekgabe ED, Mookerjee I. The effects of relaxin on extracellular matrix remodeling in health and fibrotic disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;612:88-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Unemori EN, Amento EP. Relaxin modulates synthesis and secretion of procollagenase and collagen by human dermal fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:10681-10685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Mookerjee I, Hewitson TD, Halls ML, Summers RJ, Mathai ML, Bathgate RA, Tregear GW, Samuel CS. Relaxin inhibits renal myofibroblast differentiation via RXFP1, the nitric oxide pathway, and Smad2. FASEB J. 2009;23:1219-1229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Konopka JA, Hsue LJ, Dragoo JL. Effect of Oral Contraceptives on Soft Tissue Injury Risk, Soft Tissue Laxity, and Muscle Strength: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Orthop J Sports Med. 2019;7:2325967119831061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Xu T, Bai J, Xu M, Yu B, Lin J, Guo X, Liu Y, Zhang D, Yan K, Hu D, Hao Y, Geng D. Relaxin inhibits patellar tendon healing in rats: a histological and biochemical evaluation. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20:349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chawla JJ, Arora D, Sandhu N, Jain M, Kumari A. Pubic Symphysis Diastasis: A Case Series and Literature Review. Oman Med J. 2017;32:510-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bahlmann F, Merz E, Macchiella D, Weber G. [Ultrasound imaging of the symphysis fissure for evaluating damage to the symphysis in pregnancy and postpartum]. Z Geburtshilfe Perinatol. 1993;197:27-30. [PubMed] |