Published online Jan 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i1.36

Peer-review started: July 29, 2020

First decision: September 30, 2020

Revised: October 27, 2020

Accepted: November 9, 2020

Article in press: November 9, 2020

Published online: January 6, 2021

Processing time: 156 Days and 1.9 Hours

Hemorrhoidal prolapse is a common benign disease with a high incidence. The treatment procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids (PPH) remains an operative method used for internal hemorrhoid prolapse. Although it is related to less pos-operative pain, faster recovery and shorter hospital stays, the postoperative recurrence rate is higher than that of the Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy (MMH). We have considered that recurrence could be due to shortage of the pulling-up effect. This issue may be overcome by using lower purse-string sutures [modified-PPH (M-PPH)].

To compare the therapeutic effects and the patients’ satisfaction after M-PPH, PPH and MMH.

This retrospective cohort study included 1163 patients (M-PPH, 461; original PPH, 321; MMH, 381) with severe hemorrhoids (stage III/IV) who were admitted to The 2nd Affiliated Hospital and Yuying Children’s Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University from 2012 to 2014. Early postoperative complications, efficacy, postoperative anal dysfunction and patient satisfaction were compared among the three groups. Established criteria were used to assess short- and long-term postoperative complications. A visual analog scale was used to evaluate postoperative pain. Follow-up was conducted 5 years postoperatively.

Length of hospital stay and operating time were significantly longer in the MMH group (8.05 ± 2.50 d, 19.98 ± 4.21 min; P < 0.0001) than in other groups. The incidence of postoperative anastomotic bleeding was significantly lower after M-PPH than after PPH or MMH (1.9%, 5.1% and 3.7%; n = 9, 16 and 14; respectively). There was a significantly higher rate of sensation of rectal tenesmus after M-PPH than after MMH or PPH (15%, 8% and 10%; n = 69, 30 and 32; respectively). There was a significantly lower rate of recurrence after M-PPH than after PPH (8.7% and 18.8%, n = 40 and 61; P < 0.0001). The incidence of postoperative anal incontinence differed significantly only between the MMH and M-PPH groups (1.3% and 4.3%, n = 5 and 20; P = 0.04). Patient satisfaction was significantly greater after M-PPH than after other surgeries.

M-PPH has many advantages for severe hemorrhoids (Goligher stage III/IV), with a low rate of anastomotic bleeding and recurrence and a very high rate of patient satisfaction.

Core Tip: In total, 1163 patients were treated for severe prolapsed hemorrhoids using modified procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids (M-PPH), conventional hemorrhoidectomy, or Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy. The short-term postoperative complications, postoperative anal dysfunction and therapeutic effects of the three treatment methods were compared. M-PPH has many advantages compared to traditional surgical treatments, including a higher degree of effectiveness, a significantly lower recurrence rate than the original PPH, and a higher rate of patient satisfaction.

- Citation: Chen YY, Cheng YF, Wang QP, Ye B, Huang CJ, Zhou CJ, Cai M, Ye YK, Liu CB. Modified procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids: Lower recurrence, higher satisfaction. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(1): 36-46

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i1/36.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i1.36

Hemorrhoidal prolapse is a common benign condition with a high prevalence. The prevalence of hemorrhoids is reported to be about 40%, as high as 80% in asymptomatic hemorrhoids[1,2]. The incidence rate of anorectal diseases in adults is about 50.1%. Approximately 520 million people were found to suffer from anorectal disease to different degrees in China’s 2015 anorectal disease epidemiology survey; 98.08% of these individuals had hemorrhoid symptoms[3].

On the basis of the severity of the clinical features, the Goligher classification divides hemorrhoids into four grades[4]. Treatment of hemorrhoids requires selective treatment based on individual symptoms and complications, and most patients with hemorrhoid (grade I/II) can be treated conservatively, including dietary changes with sufficient fluids and fiber while limiting prolonged toilet use. Surgery is still the treatment of choice for patients who fail conservative treatment and those who have grade III or IV hemorrhoids with active bleeding or persistent prolapse. There are currently many types of surgical treatments for hemorrhoids, with traditional hemorrhoid operations consisting of Milligan–Morgan[5] or Ferguson procedures and diathermy hemorrhoidectomy[6,7]. However, severe postoperative pain and a high rate of postoperative recurrence are the main reasons for low patient satisfaction and why the traditional surgical techniques are not highly recommended.

In an effort to reduce postoperative pain, Longo[8] introduced the procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids (PPH) in 1998. It is a new procedure that has become widely accepted and recommended as a treatment for hemorrhoids. Over the past two decades, numerous systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials have reported that PPH results in a shorter length of inpatient stay, less postoperative pain and greater patient satisfaction rate than the conventional hemorrhoidectomy[9-12]. However, in terms of the long-term outcomes, there is a higher incidence of recurrence or serious complications after PPH, such as anal incontinence, anal stenosis and even rectovaginal fistulae[13-17]. Hence, a growing number of surgeons and patients are rejecting PPH.

We consider that one of the reasons for the persistent recurrence of hemorrhoid prolapse may be that purse-string sutures are placed too high to provide the pull-up effect. Consequently, we have designed a modified PPH (M-PPH) with lower purse-string sutures. In this study, we retrospectively studied different surgical techniques for the treatment of severe hemorrhoids, including MMH, conventional PPH and M-PPH with a 5-year follow-up period.

We retrospectively studied 1163 inpatients who underwent surgery for grade III/IV hemorrhoid prolapse at The 2nd Affiliated Hospital and Yuying Children’s Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University from January 2012 to December 2014. We compared groups of patients treated with MMH, traditional PPH or M-PPH. None of the patients had a history of previous perianal surgery. Patients who had grade I/II hemorrhoids and those who had previous surgery for perianal disease, affected by other anal pathologies (e.g., anal fissure), inflammatory bowel disease, anal stenosis and/or coexistent bleeding disorders were not included in this study. Patients who died during the follow-up or who refused the 5-year follow-up examination were excluded from the analysis.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the 2nd Affiliated Hospital and of Wenzhou Medical University.

Preoperative assessment included clinical data collection and rectal examination. During the examination, the following variables were assessed: Sex, age, previous treatment (e.g., drugs), local symptoms (e.g., pain, bleeding, prolapse or anal stenosis) and defecation habits. Specialist examination was also performed, including digital anal examination and anoscopy. Colonoscopy was recommended for patients over 50-years-old or who were at risk for colorectal disease. The anatomical grade of hemorrhoids was recorded according to the Goligher classification[3].

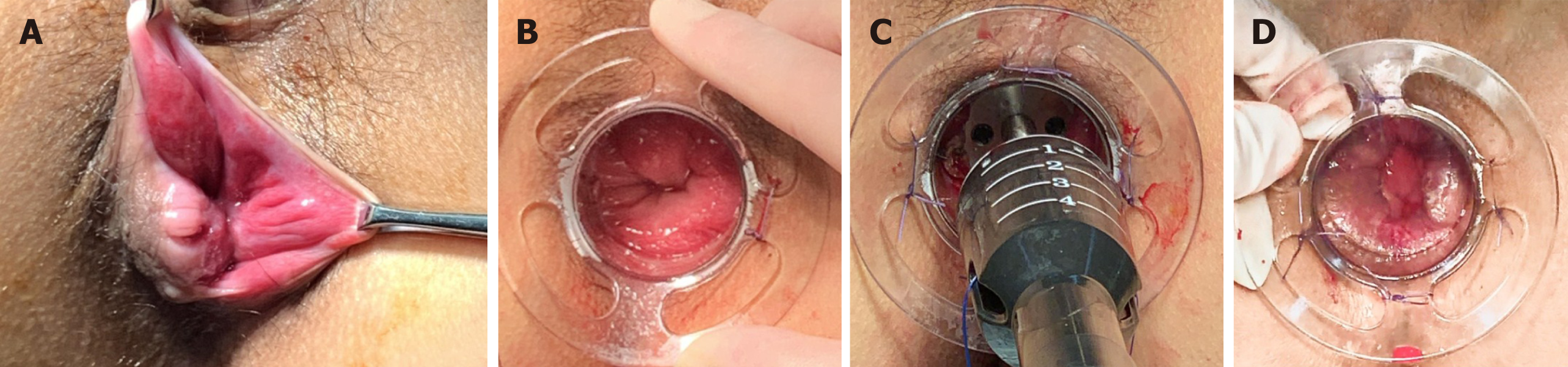

For M-PPH (Figure 1), double purse-string sutures were inserted: One was 0.5-1.0 cm above the dentate line, and the other was 0.5 cm from the distal of the first purse-string suture. For original PPH, purse-string sutures were applied 4 cm from the dentate line[8]. A PPH03 hemorrhoidal circular stapler (Ethicon hemorrhoidal circular stapler, Cincinnati, OH, United States) was used for both the original PPH and M-PPH procedures. Furthermore, conventional Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy was performed as described by Goligher[4]. MMH was performed under Yaoshu point anesthesia, while the other procedures were performed mainly under spinal anesthesia. Perioperatively, all patients received two doses of a second-generation cephalosporin. Postoperative analgesia consisted of ketorolac tromethamine (60 mg, twice a day) and celecoxib (200 mg, twice a day). Patients were advised to wash their perianal wound with water after defecation and use mupirocin ointment for external application.

Short-term postoperative complications were recorded during hospitalization: (1) Patients’ postoperative pain was recorded at four timepoints after the operation (first defection, day 1, day 3, day 5), as assessed by the visual analogue scale[18] (VAS; 0 indicating no pain and 10 indicating the worst pain); (2) Operative time (min); (3) Postoperative hospital stay (days); (4) Anastomotic bleeding (anastomotic hemorrhage found by anoscopy); and (5) Sensation of rectal tenesmus (a feeling of defecating even when the rectum is empty). Postoperative review was conducted at our outpatient department at 1, 2 and 4 wk after surgery. Thereafter, regular examinations were performed according to the patient’s wishes. All of the patients were contacted by telephone during the 5-year follow-up. The mean follow-up period was 5 ± 0.5 (range: 4–6) years. Patients were invited to the clinic for the final evaluation if the following symptoms appeared during follow-up: (1) Postoperative anal discharge (wet anus or anal discharge caused by the scar left by the surgery)[19]; (2) Postoperative sensory anal incontinence (lack of control over defecation resulting in unconscious discharge of gas or stool); (3) Postoperative anal stenosis (a condition involving narrowed stool and/or only liquid stools); and (4) Postoperative recurrence of hemorrhoids (continuous prolapse of perianal mass or hematochezia recurred after hemorrhoidectomy).

Five years after the operation, telephonic follow-up was used to investigate patient satisfaction. A scale of 1–4 (1 = dissatisfied, 2 = poorly satisfied, 3 = satisfied, 4 = very satisfied) was provided to the patient.

SPSS for Windows (version 22.0) was used for all statistical analyses. Continuous variables are presented as means ± standard deviation or medians (range). Statistical analyses were performed using the chi-square test and ANOVA. Kruskal-Wallis H tests were used for variables with non-normal distributions to assess differences in the VAS between the MMH, PPH and M-PPH groups (all pairwise for multiple comparisons). The data processing and graphics produced were carried out using R statistics software (The R Foundation, Vienna, Austria). P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Bo Ye from the Department of Biostatistics, School of Public Health, State University of New York at Albany.

Patients’ characteristics are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences among the patient groups in terms of sex, age or grade of hemorrhoids.

| Variable | MMH, n = 381 | PPH, n = 321 | M-PPH, n = 461 | P value |

| Male/Female | 190/191 | 153/168 | 261/200 | 0.770 |

| Age in yr | 46 (17-84) | 46 (18-87) | 46 (17-86) | 0.357 |

| Grade of hemorrhoids | ||||

| III | 321 (81.9) | 263 (81.9) | 394 (85.5) | 0.219 |

| IV | 69 (18.1) | 58 (18.1) | 67 (14.5) | 0.152 |

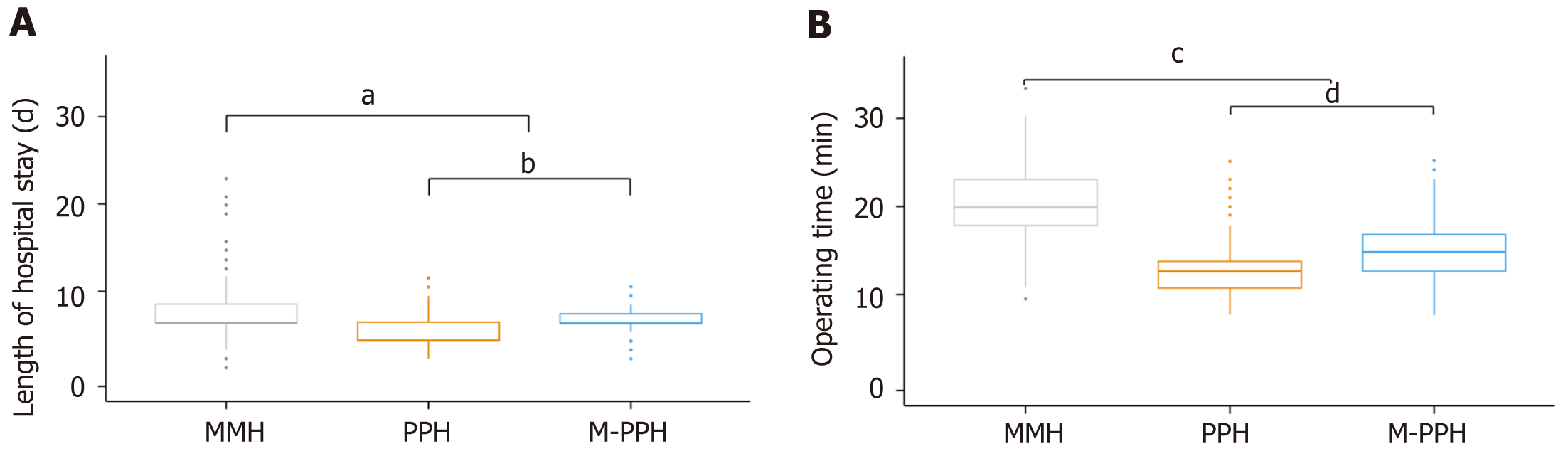

The mean length of hospital stay and operating time were markedly greater after MMH (8.05 ± 2.50 d, 19.98 ± 4.21 min; respectively) than after the other surgeries (P < 0.0001; Figure 2). On the other hand, there was a significant difference between M-PPH (7.24 ± 1.30 d, 15.55 ± 3.27 min; respectively) and PPH (6.13 ± 1.93 d, 13.30 ± 2.74 min; respectively) in terms of the mean length of hospital stay and the mean operating time (P < 0.0001; Figure 2).

Postoperative pain VAS scores for the three groups are presented in Table 2. On Kruskal-Wallis H analysis at all timepoints, the postoperative VAS scores in the MMH group were significantly higher than in the other two groups (all P < 0.0001). Among the two PPH procedures, the postoperative pain scores in the PPH was significantly lower than in the M-PPH group (P < 0.0001).

| Variable | MMH, n = 381 | PPH, n = 321 | M-PPH, n = 461 | P value1 |

| First defecation | 5 (4-6) | 3 (2-6) | 4 (3-7) | < 0.001 |

| Day 1 | 3 (2-6) | 2 (1-5) | 3 (2-7) | < 0.001 |

| Day 3 | 3 (2-5) | 2 (1-4) | 2 (2-5) | < 0.001 |

| Day 5 | 2 (2-5) | 1 (1-3) | 2 (2-5) | < 0.001 |

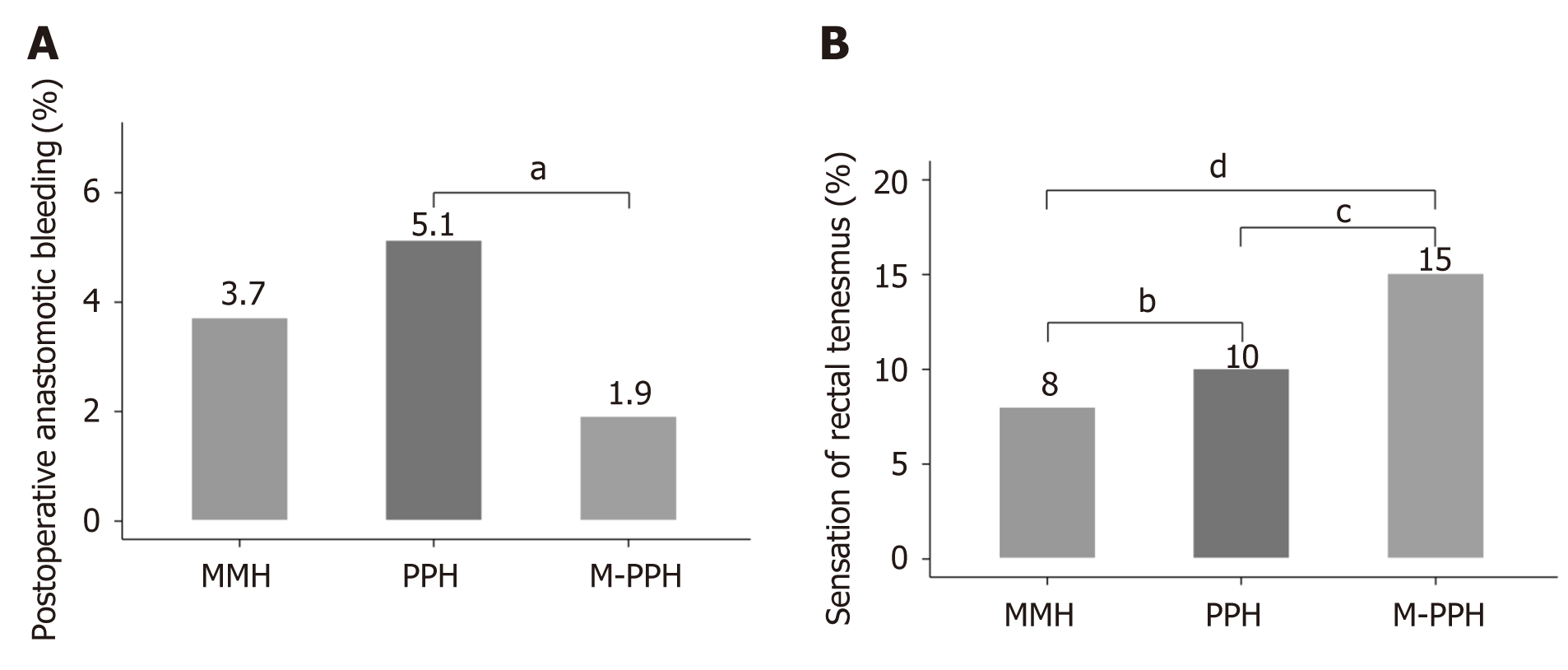

The rate of postoperative anastomotic bleeding was low in all procedures (M-PPH: 1.9%, PPH: 5.1%, MMH: 3.7%), and the incidence in the M-PPH group was significantly lower than in the PPH group (P < 0.0001; Figure 3A). Five patients who failed to respond to conservative treatment who repeatedly experienced anastomotic bleeding after M-PPH were treated with an 8-shape suture in an outpatient operation, after which bleeding ceased.

Among the various procedures, the rate of sensation of rectal tenesmus after M-PPH was significantly higher than after MMH (15% and 8%, respectively; P < 0.0001) or PPH (10%, P = 0.008; Figure 3B).

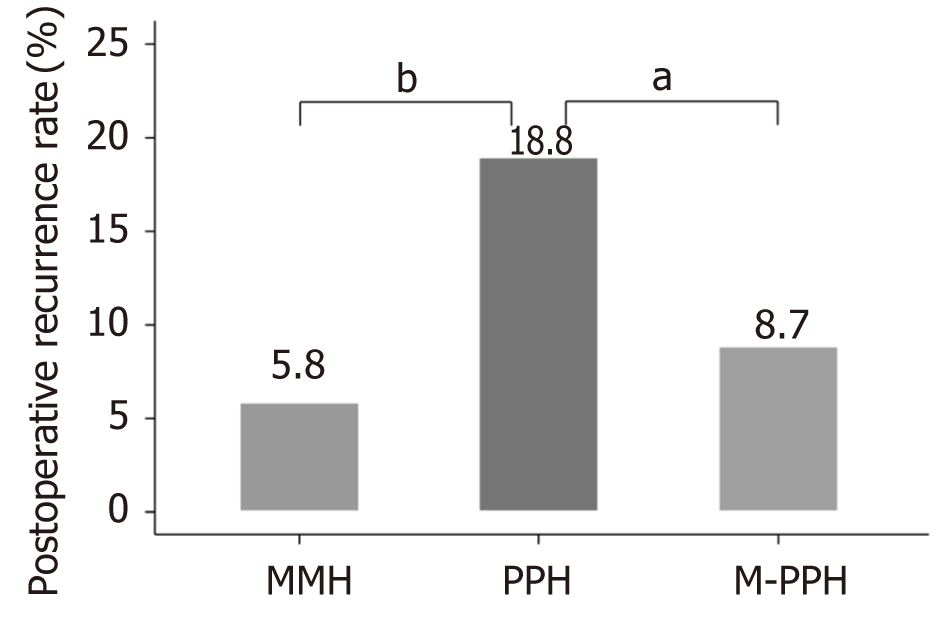

The postoperative recurrence rates of the MMH, PPH and M-PPH groups are summarized in Figure 4. It is noteworthy that the postoperative recurrence rate was significantly lower in the M-PPH group than that in the PPH group (8.7% and 18.8%, respectively; P < 0.0001). The postoperative recurrence rate in the MMH group was significantly lower than in the PPH group (5.8%, P < 0.0001). However, no significant difference was found between the M-PPH and MMH groups.

Recurrent prolapse was successfully treated using MM surgery in 5 of 22 patients (22.7%) of the MMH group. The remaining 17 patients (77.3%) with recurrent symptomatic second-degree hemorrhoids were treated with sclerotherapy. In the PPH group, 15 of the 60 patients (25.0%) had a recurrent symptomatic third-degree hemorrhoids and underwent MM surgery. Forty-five patients (75.0%) with recurrent second-degree hemorrhoids were treated with sclerotherapy. Thirteen patients (67.5%) in the M-PPH group had recurrent symptomatic third-degree hemorrhoids and underwent MM surgery. The remaining 27 of 40 patients (32.5%) with recurrent second-degree hemorrhoids were treated with sclerotherapy.

Overall, the reoperation rates were 1.3%, 4.7% and 2.8% in the MMH, PPH and MMH groups, respectively (P < 0.001). None of these patients experienced any further recurrences during the follow-up period.

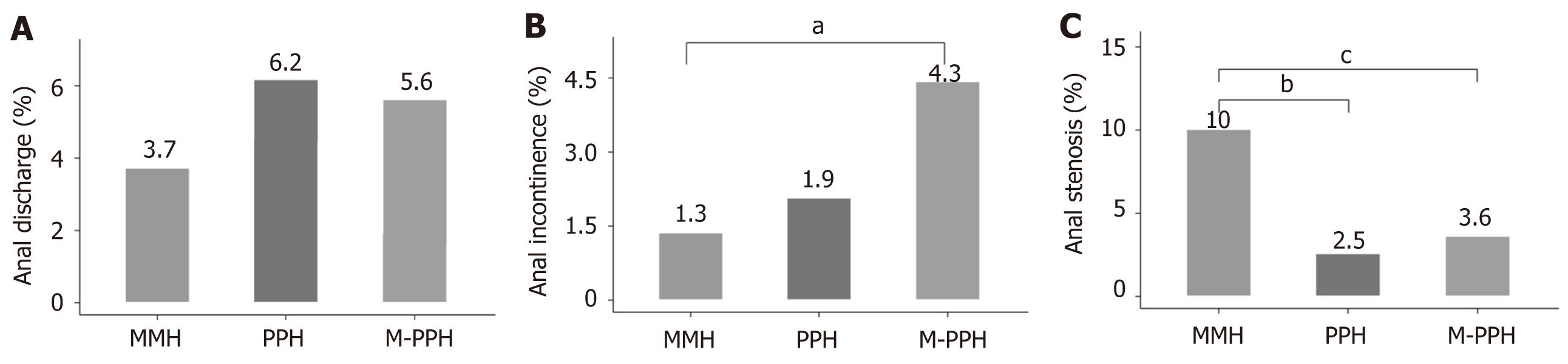

The incidence of postoperative anal discharge was higher in the PPH group (6.2%) than in the other groups, but the differences were not statistically significant (Figure 5A). The rate of postoperative anal incontinence differed significantly only between the MMH and M-PPH groups (1.3% and 4.3%, respectively; P = 0.04; Figure 5B). During the follow-up period, anal discharge or incontinence improved after 6 mo in all of these patients. The incidence of anal stenosis after MMH was significantly higher than after the other two types of surgeries (10%, P < 0.0001; Figure 5C).

The majority of patients in all groups were satisfied with their surgery. Overall, 83% (383) of the patients in the M-PPH group, 65% (200) of those in the PPH group, and 76% (290) of those in the MMH group reported being very satisfied or satisfied (score ≥ 3) with their procedures. Patient satisfaction for the three groups is presented in Table 3.

| Group | Very satisfied | Satisfied | Poorly satisfied | Dissatisfied |

| MMH, n = 381 | 236 (61.9) | 54 (14.2) | 38 (10.0) | 53 (13.9) |

| PPH, n = 321 | 105 (32.7) | 95 (29.6) | 89 (27.7) | 32 (10.0) |

| M-PPH, n = 461 | 266 (57.7) | 117 (25.4) | 46 (10.0) | 32 (6.9) |

PPH offers unique advantages over traditional hemorrhoidectomy, such as shorter length of hospital stay, less postoperative pain and fewer lost workdays[9-12]. However, high postoperative recurrence and serious long-term postsurgical complications have been reported[2,13-17]. To address these complications, we have devised a new M-PPH procedure characterized by lower placement of the double purse-string sutures. Here, we compared the effects and postoperative complications of the M-PPH, PPH and MMH. We showed that the M-PPH is superior to traditional surgery for severe hemorrhoids (stage III/IV) in the rate of anastomotic bleeding, recurrence and patient satisfaction.

The time of hospitalization was mainly related to the duration of postoperative pain, with the length of hospitalization in the M-PPH group being significantly longer than that in the PPH group. One probable reason for this is that the lower level of resection and lower placement of double purse-string sutures might have reduced the blood flow from the internal iliac artery to the anal anastomosis[18]. Another possible reason is that postoperative inflammatory stimulation affected the anal spinal nerve because the anastomotic site of the M-PPH procedure is closer to the dentate line. On the other hand, as reported in other previous research papers, there was a significant increase in the length of hospitalization and lost work days following MMH[9-12]. Prolonged pain after MMH appears to be due to mechanical irritation of the open anal wound from fecal transport and inevitable thermal damage from the electric knife.

The postoperative pain of the MMH group was significantly higher at each timepoint than in the other groups. Similar results have previously been reported in the literature[10,20,21]. There was also a difference in the types of pain experienced by patients after the MMH or PPH. After open hemorrhoidectomy, the pain felt by patients tended to be cutting and sharp, while that after PPH involved a distended discomfort or more vague pain. This was not surprising because the PPH technique does not involve excision of the perianal skin. However, for M-PPH, placement of the purse-string suture closer to the dentate line resulted in more severe postoperative pain[9,22].

The lower stapling height used for M-PPH resulted in full exposure of the operative field; thus, it was easy to find the bleeding point and stop bleeding during the operation. Another possible reason for the significant reduction in anastomotic bleeding after M-PPH compared to PPH is that the height of the load suture caused the removal of the hemorrhoidal vascular plexus, resulting in low blood flow to the anus through the collateral circulation of the inferior rectal artery[16].

The rate of the postoperative sensation of rectal tenesmus was significantly higher after M-PPH than after PPH. One possible reason is that the area in the rectum ampulla that controls defecation was affected by the purse-string sutures, thereby causing the anal cushions to more easily create a sense of defecation[23]. To address the high rate of sensation of rectal tenesmus after M-PPH, we teach and encourage patients to perform levator ani muscle training early after surgery, and the symptoms gradually disappear 1-2 mo after surgery.

Recurrence of hemorrhoids is a major concern for patients and indicates failure of surgery; thus, it is a matter of great concern among both patients and surgeons. M-PPH had a significantly lower recurrence rate than PPH. This recurrence rate is comparable to that reported in previous research on the M-PPH[20]. The most plausible reasons are the lower level placement of the purse-string sutures and the use of double purse-string sutures. The closer the anastomosis is to the dentate line, the better the result with the lower anastomosis pulling up the hemorrhoids more effectively. With the anastomosis scarring, the anal cushions near the dentate line are turned inward and are better fixed, while the double purse-string sutures also allow for more tissue traction towards the rectum for more effective lifting by the anal cushions[24]. On the other hand, because of patients’ misperceptions regarding recurrence, we think that the relapse rate may be overestimated. It is hard for patients to distinguish between skin tags and prolapse recurrence. Among the 50 patients examined by Ganio et al[25], only 6 of the 9 patients who reported recurrent hemorrhoidal prolapse in telephone interviews were found to have recurrence on proctologic examination. A recent meta-analysis on the identification of residual skin tags and recurrence concluded that the high recurrence rates in the literature are often attributed to the misrecognition of residual skin tags[26]. We confirmed this at the post-operative outpatient follow-up. The incidence of skin tags and hemorrhoid prolapse is significantly higher after PPH than after conventional techniques[11]. It is unclear whether skin tag removal reduces the incidence of symptomatic recurrent prolapse. Larger, well-designed clinical studies are needed to validate the usefulness of respecting the M-PPH postoperative skin tags.

Anal incontinence is a potential complication of hemorrhoidectomies. The progression of anal incontinence after hemorrhoidectomy seems to be multifactorial[27,28]. In this study, the rate of anal incontinence in M-PPH was higher than in the other procedures. Damage to the dentate line and anal cushions may play a role in anal incontinence likely due to lower anastomosis[24,29]. However, normal sphincter systolic pressure and rectoanal inhibitory reflexes are actually necessary to ensure anal homeostasis[30]. After hemorrhoidectomy, the integrity and sensitivity of the anal cushions are not sufficient to ensure bowel control[31]. Hence, complete retention of the anal cushions during surgery is not crucial; it is possible to remove some of the tissue if necessary. No serious loss of anal control was observed in our study. Patients only exhibited perianal moist discomfort or decreased control of gas and fluids, and the frequency and severity of the symptoms gradually disappeared 6 mo after surgery. Because we did not have any data assessing anorectal function by anorectal manometry, anal action potentials or intra-anal ultrasound, we could not define the underlying mechanism of anorectal incontinence after hemorrhoid surgery. On the other hand, the rate of anal incontinence is also high after MMH, which may be due to the need to remove part of the perianal skin intraoperatively. After MMH, the skin of the anal canal forms a poorly elastic scar and results in poor anal closure.

The rate of postoperative anal stenosis in the MMH group was significantly higher than in the other two groups. It is understandable, considering that the skin of the anal canal formed a scar with poor elasticity after MMH due to excision of the anal cushions and perianal skin.

We have found that “success” is not the only criterion for determining patient satisfaction after surgery. Patients’ satisfaction is affected by numerous elements, including their subjective perceptions. Most patients were satisfied with the postoperative efficacy, although there were some postoperative complications in all three groups. The M-PPH group had a high rate of patient satisfaction, but they had an obvious sensation of rectal tenesmus and a high incidence of anal incontinence.

A potential limitation of this study is its retrospective nature; hence, a prospective randomized controlled study is needed to confirm these findings. Another limitation is that, although a phone interview is a convenient and easy method of data collection, a direct clinical examination of all patients and a full clinical evaluation during the follow-up is lacking. Patients are often not able to distinguish skin tags from real hemorrhoids, and thus, the recurrence rate may be overestimated.

In summary, this study found that, within the follow-up period of 5 years, M-PPH has many advantages, including a lower recurrence rate and a higher patient satisfaction rate than conventional PPH. Nevertheless, M-PPH is associated with higher rates of sensation of rectal tenesmus and of anal incontinence.

Hemorrhoidal prolapse is a common benign disease with a high incidence. The procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids (PPH) remains the first-line therapy for hemorrhoids. Although it is related to less post-operative pain, faster recovery and shorter hospital stays, the postoperative recurrence rate is higher than that of the Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy (MMH).

This retrospective cohort study included 1163 patients [modified-PPH (M-PPH), 461; original PPH, 321; MMH, 381] with severe hemorrhoids (stage III/IV) who were admitted to The 2nd Affiliated Hospital and Yuying Children’s Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University from 2012 to 2014. We wanted to compare the early postoperative complications, efficacy, postoperative anal dysfunction and patient satisfaction after M-PPH, PPH and MMH.

To assess the clinic efficacy and patient satisfaction towards treating severe hemorrhoids through M-PPH, PPH and MMH.

This retrospective cohort study included 1163 patients with severe hemorrhoids who were admitted to The 2nd Affiliated Hospital and Yuying Children’s Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University from 2012 to 2014. Early postoperative complications, efficacy, postoperative anal dysfunction and patient satisfaction were compared among the three groups. Established criteria were used to assess short- and long-term postoperative complications. A visual analog scale was used to evaluate postoperative pain. Follow-up was conducted 5 years postoperatively.

M-PPH has many advantages for patients with severe hemorrhoids (Goligher stage III/IV) with a low rate of anastomotic bleeding and recurrence while gaining a very high rate of patient satisfaction.

The lower anastomosis can pull up the rectal mucosa more effectively resulting in a lower the recurrence rate.

The prospective randomized controlled trial is a more scientific and rigorous research method and is the best method for the future research.

We gratefully thank the patients and their families for participating in this study.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Quesada BM, Rosen SA S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Haas PA, Haas GP, Schmaltz S, Fox TA Jr. The prevalence of hemorrhoids. Dis Colon Rectum. 1983;26:435-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zhang G, Liang R, Wang J, Ke M, Chen Z, Huang J, Shi R. Network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing the procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids, Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy and tissue-selecting therapy stapler in the treatment of grade III and IV internal hemorrhoids(Meta-analysis). Int J Surg. 2020;74:53-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Anorectal Branch of China Association of Chinese Medicine. The latest results of the national epidemic survey of anorectal diseases have been released. Shijie Zhongxiyi Jiehe Zazhi. 2015;10:1489. |

| 4. | Goligher JC. Surgery of the anus rectum and colon. 4th edition. London: Bailliere, Tindall 1980: 93-149. |

| 5. | Milligan ET, Morgan CN, Jones LE, Officer R. Surgical anatomy of the anal canal and operative treatment of haemorrhoids. Lancet. 1937;2:1119-1124. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 368] [Cited by in RCA: 263] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sharif HI, Lee L, Alexander-Williams J. Diathermy haemorrhoidectomy. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1991;6:217-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gallo G, Realis Luc A, Clerico G, Trompetto M. Diathermy excisional haemorrhoidectomy - still the gold standard - a video vignette. Colorectal Dis. 2018;20:1154-1156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Longo A. Treatment of hemorrhoidal disease by reduction of mucosa and hemorrhoidal prolapse with a circular suturing device: a new procedure. In: Proceedings of the 6th World Congress of Endoscopic Surgery; 1998 Jun 3-6; Rome, Italy. Bologna: Monduzzi Editore, 1998: 777–784. |

| 9. | Mehigan BJ, Monson JR, Hartley JE. Stapling procedure for haemorrhoids versus Milligan-Morgan haemorrhoidectomy: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;355:782-785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rowsell M, Bello M, Hemingway DM. Circumferential mucosectomy (stapled haemorrhoidectomy) versus conventional haemorrhoidectomy: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;355:779-781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 274] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Nisar PJ, Acheson AG, Neal KR, Scholefield JH. Stapled hemorrhoidopexy compared with conventional hemorrhoidectomy: systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1837-1845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lu M, Yang B, Liu Y, Liu Q, Wen H. Procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids vs traditional surgery for outlet obstructive constipation. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:8178-8183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | McDonald PJ, Bona R, Cohen CR. Rectovaginal fistula after stapled haemorrhoidopexy. Colorectal Dis. 2004;6:64-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Angelone G, Giardiello C, Prota C. Stapled hemorrhoidopexy. Complications and 2-year follow-up. Chir Ital. 2006;58:753-760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mlakar B, Kosorok P. Complications and results after stapled haemorrhoidopexy as a day surgical procedure. Tech Coloproctol. 2003;7:164-7; discussion 167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Pescatori M, Gagliardi G. Postoperative complications after procedure for prolapsed hemorrhoids (PPH) and stapled transanal rectal resection (STARR) procedures. Tech Coloproctol. 2008;12:7-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tjandra JJ, Chan MK. Systematic review on the procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids (stapled hemorrhoidopexy). Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:878-892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 226] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Raahave D, Jepsen LV, Pedersen IK. Primary and repeated stapled hemorrhoidopexy for prolapsing hemorrhoids: follow-up to five years. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:334-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wang ZG, Zhang Y, Zeng XD, Zhang TH, Zhu QD, Liu DL, Qiao YY, Mu N, Yin ZT. Clinical observations on the treatment of prolapsing hemorrhoids with tissue selecting therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:2490-2496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Iida Y, Saito H, Takashima Y, Saitou K, Munemoto Y. Procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids (PPH) with low rectal anastomosis using a PPH 03 stapler: low rate of recurrence and postoperative complications. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2017;32:1687-1692. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Mattana C, Coco C, Manno A, Verbo A, Rizzo G, Petito L, Sermoneta D. Stapled hemorrhoidopexy and Milligan Morgan hemorrhoidectomy in the cure of fourth-degree hemorrhoids: long-term evaluation and clinical results. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1770-1775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Seow-Choen F. Stapled haemorrhoidectomy: pain or gain. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1-3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Read MG, Read NW, Haynes WG, Donnelly TC, Johnson AG. A prospective study of the effect of haemorrhoidectomy on sphincter function and faecal continence. Br J Surg. 1982;69:396-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Situ GW, Du HS. [Analysis of the relationship between stoma position and postoperative effects of procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids in the treatment of hemorrhoids]. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2005;43:1506-1507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ganio E, Altomare DF, Gabrielli F, Milito G, Canuti S. Prospective randomized multicentre trial comparing stapled with open haemorrhoidectomy. Br J Surg. 2001;88:669-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gao XH, Fu CG, Nabieu PF. Residual skin tags following procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids: differentiation from recurrence. World J Surg. 2010;34:344-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Fenger C, Lyon H. Endocrine cells and melanin-containing cells in the anal canal epithelium. Histochem J. 1982;14:631-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Speakman CT, Burnett SJ, Kamm MA, Bartram CI. Sphincter injury after anal dilatation demonstrated by anal endosonography. Br J Surg. 1991;78:1429-1430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Thekkinkattil DK, Dunham RJ, O'Herlihy S, Finan PJ, Sagar PM, Burke DA. Measurement of anal cushions in idiopathic faecal incontinence. Br J Surg. 2009;96:680-684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Read NW, Harford WV, Schmulen AC, Read MG, Santa Ana C, Fordtran JS. A clinical study of patients with fecal incontinence and diarrhea. Gastroenterology. 1979;76:747-756. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Gibbons CP, Trowbridge EA, Bannister JJ, Read NW. Role of anal cushions in maintaining continence. Lancet. 1986;1:886-888. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |