Published online Jan 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i1.24

Peer-review started: June 27, 2020

First decision: September 30, 2020

Revised: October 9, 2020

Accepted: November 2, 2020

Article in press: November 2, 2020

Published online: January 6, 2021

Processing time: 188 Days and 9.3 Hours

Signet ring cell carcinoma is a rare type of oesophageal cancer, and we hypothesized that log odds of positive lymph nodes (LODDS) is a better prognostic factor for oesophageal signet ring cell carcinoma.

To explore a novel prognostic factor for oesophageal signet ring cell carcinoma by comparing two lymph node-related prognostic factors, log odds of positive LODDS and N stage.

A total of 259 cases of oesophageal signet ring cell carcinoma after oesopha-gectomy were obtained from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database between 2006 and 2016. The prognostic value of LODDS and N stage for oesophageal signet ring cell carcinoma was evaluated by univariate and multivariate analyses. The Akaike information criterion and Harrell’s C-index were used to assess the value of two prediction models based on lymph nodes. External validation was performed to further confirm the conclusion.

The 5-year cancer-specific survival (CSS) and 5-year overall survival (OS) rates of all the cases were 41.3% and 27.0%, respectively. The Kaplan-Meier method showed that LODDS had a higher score of log rank chi-squared (OS: 46.162, CSS: 41.178) than N stage (OS: 36.215, CSS: 31.583). Univariate analyses showed that insurance, race, T stage, M stage, TNM stage, radiation therapy, N stage, and LODDS were potential prognostic factors for OS (P < 0.1). The multivariate Cox regression model showed that LODDS was an significant independent prognostic factor for oesophageal signet ring carcinoma patients after surgical resection (P < 0.05), while N stage was not considered to be a significant prognostic factor (P = 0.122). Model 2 (LODDS) had a higher degree of discrimination and fit than Model 1 (N stage) (LODDS vs N stage, Harell’s C-index 0.673 vs 0.656, P < 0.001; Akaike information criterion 1688.824 vs 1697.519, P < 0.001). The results of external validation were consistent with those in the study cohort.

LODDS is a superior prognostic factor to N stage for patients with oesophageal signet ring cell carcinoma after oesophagectomy.

Core Tip: This study showed that log odds of positive lymph nodes (LODDS) was an independent prognostic factor for oesophageal signet ring carcinoma patients after surgical resection, while N stage was not considered to be a significant prognostic factor. Prognosis model based on LODDS had a higher degree of discrimination and fit than the model based on N stage. In conclusion, LODDS is a superior prognostic factor to N stage for patients with signet ring cell carcinoma after oesophagectomy.

- Citation: Wang F, Gao SG, Xue Q, Tan FW, Gao YS, Mao YS, Wang DL, Zhao J, Li Y, Yu XY, Cheng H, Zhao CG, Mu JW. Log odds of positive lymph nodes is a better prognostic factor for oesophageal signet ring cell carcinoma than N stage. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(1): 24-35

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i1/24.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i1.24

Signet ring cell (SRC) carcinoma is a rare subtype of adenocarcinomas. The first article describing SRC carcinoma in the oesophagus was published in 1978[1]. According to relevant literature reports, approximately 3.5%–5.0% of oesophageal carcinomas are SRC carcinoma[2-4]. SRC is characterized by the appearance of a large vacuole containing mucin, which squeezes the nucleus to the periphery of the cancer cell, making the shape of cell look like a signet ring[5,6]. Based on the World Health Organization classification system, the definition of SRC carcinoma is an adenocarcinoma in which isolated or groups of signet ring cells can be observed in more than 50% of the tumour stroma[7]. SRCs are currently found in colorectal cancer, prostate cancer, bladder cancer, breast cancer, gastric cancer, and other adenocarcinomas. Several studies have shown that as a highly malignant tumour, SRC carcinoma had a worse prognosis[2-8]. Because SRC carcinoma is more common in gastric cancer, more research on SRC carcinoma focuses on gastric cancer. Currently, there are few studies on SRC carcinoma of the oesophagus.

Currently, according to the 8th edition of American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging system, N stage based on the number of metastatic lymph nodes is still the most commonly used prognostic indicator for oesophageal cancer[9]. However, incomplete lymph node dissection may result in an inaccurate number of positive lymph nodes, which is less than the actual number. This phenomenon is known as stage migration[10,11].

Recently, positive lymph node ratio (LNR), defined as the ratio of metastatic lymph nodes to total dissected lymph nodes, has shown a better correlation with prognosis than N stage, especially when the lymph node dissection during surgery is inadequate. However, some different conclusions suggest that LNR is not superior in predicting prognosis[12,13]. In particular, when no metastatic lymph nodes were dissected, evaluation methods based on LNR could not accurately distinguish the heterogeneity.

Log odds of positive lymph nodes (LODDS) is a novel prognostic factor associated with lymph nodes. LODDS is calculated as the natural logarithm of the ratio of positive to negative lymph nodes[14]. In several studies, LODDS has already been confirmed to be a better prognostic factor for bladder cancer, pancreatic cancer, rectal cancer, lung cancer, and oesophageal cancer[15-20]. However, the predictive value of LODDS in oesophageal SRC carcinoma has not been studied.

In this study, by comparing the value of LODDS and traditional N stage as prognostic factors for oesophageal SRC carcinoma, we expected to propose a better lymph node staging indicator for oesophageal SRC carcinoma to improve the current lymph node staging scheme.

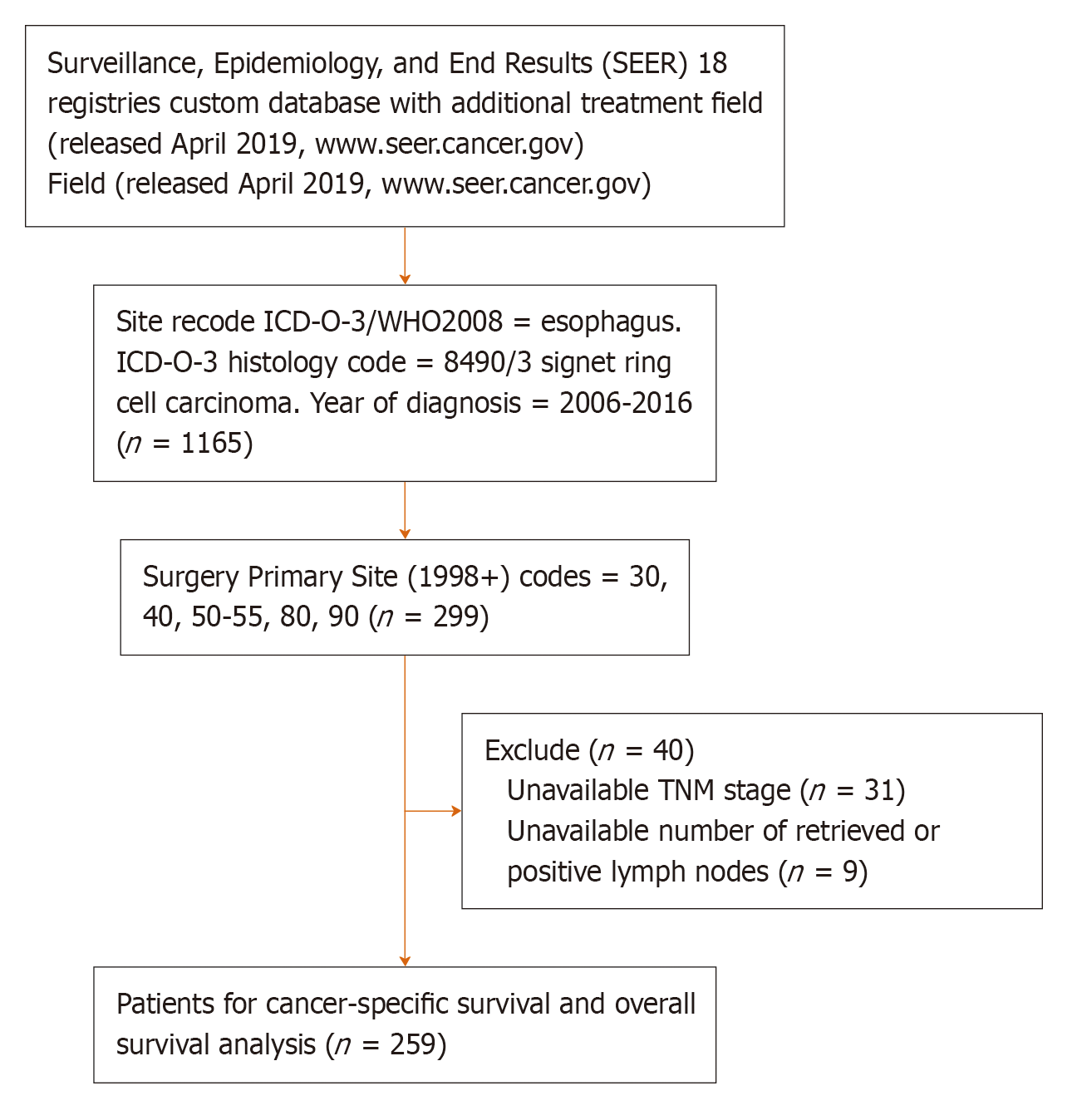

All the cases in the study cohort were from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database (SEER 18 registries database with the additional treatment field, released in April 2019, www.seer.cancer.gov), which includes approximately 30% of the United States population. SEER*Stat 8.3.6 software was installed to extract the information of patients with oesophageal SRC carcinoma diagnosed between 2006 and 2016 by surgical resection (Site recode is oesophagus, Histology code is 8490/3 signet ring cell carcinoma; Year of diagnosis is 2006-2016; Surgery Primary Site codes is 30, 40, 50-55, 80, 90). The exclusion criteria were: (1) Cases with unknown TNM stage; and (2) Cases without accurate lymph node dissection information. Ultimately, 259 cases were enrolled in our study cohort (Figure 1).

To validate the result of the study cohort, a total of 138 oesophageal SRC carcinoma patients were selected as a validation cohort from the Department of Thoracic Surgery of Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences from 2005 to 2019. All the included patients had definite TNM stage, accurate lymph node dissection information, and follow-up information.

A total of 17 variables were obtained from the SEER (18 registries custom database with additional treatment fields) database: Age, insurance, marital status, sex, race, pathology grade, T stage, N stage, M stage, AJCC TNM stage, radiation sequence with surgery, chemotherapy, the number of total lymph nodes dissected, the number of positive lymph nodes, cause of death, survival time, and vital status. Patient deaths from all causes were regarded as uncensored cases for the overall survival (OS) analysis, while the cancer-specific survival (CSS) analysis only involved deaths caused by oesophageal SRC cancer.

All cases were restaged to the latest TNM staging system according to the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual (8th edition)[9]. Age as a continuous variable was divided into three groups (≤ 60 years, 61-70 years, and > 70 years). The variable of marital status was classified into three category variables: Married, single (divorced, separated, unmarried or domestic partner, never married, widowed), and unknown. The variable insurance was divided into three groups: Insured (any Medicaid, insured, or insured/no specifics), uninsured, and unknown. LODDS was calculated as loge [(PLN + 0.5)/( NLN + 0.5)][21], where PLN is the number of positive lymph nodes, and NLN is the number of negative lymph nodes. The numerator and denominator were increased by 0.5 to avoid singularity.

X-Tile software version 3.6.1 (Yale University, United States) was used to establish the optimal cut-off values for OS analysis of LODDS in the study cohort. The LODDS was converted to three categorical variables: LODDS1 (4.55 ≤ LODDS ≤ 1.90), LODDS2 (1.89 ≤ LODDS ≤ 0.15), and LODDS3 (0.16 ≤ LODDS ≤ 4.27). OS and CSS were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed using a Cox proportional hazard regression model. Variables with statistical significance (P < 0.1) in univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis. The Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Harrell’s C-index were used to estimate the discriminative power of the Cox multivariate regression model (lower AIC indicates better model fit, and higher Harrell’s C-index indicates better degree of discrimination). All the statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 25.0 (IBM, United States) and R software version 4.0.0 (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria). The statistical significance level was set at a P value less than 0.05.

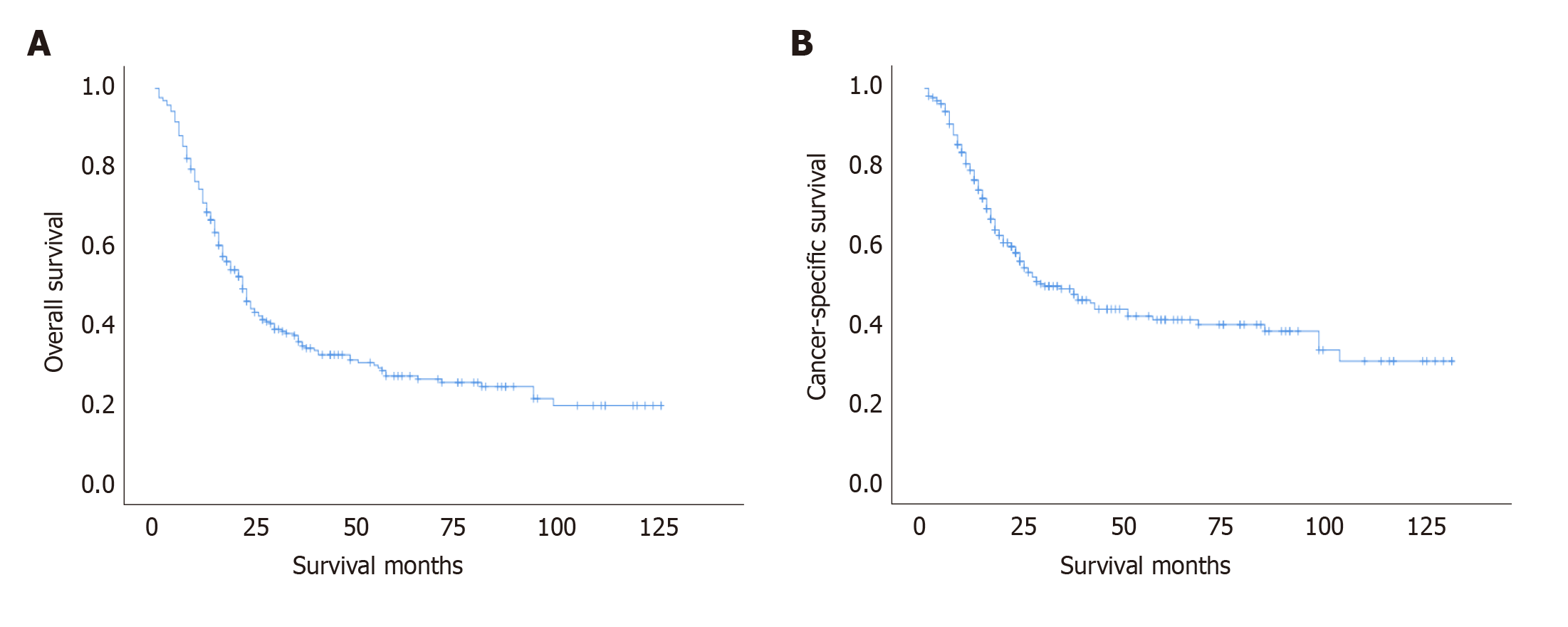

The baseline characteristics of the study cohort are shown in Table 1. A total of 259 oesophageal SRC patients with surgical resection were retained. Most of them were male (89.2%), married (77.2%), insured (83.8%), and non-Hispanic white (86.1%). The age of the majority of cases were 61-70 years (43.2%). Due to the high degree of malignancy and rapid progression of SRC, more patients were pathologically graded as grade III-IV (82.6%), and more patients had stage III disease (50.2%) according to the TNM stage system (as stage IV patients were rarely treated by surgery, without accurate lymph node information, they were excluded from the cohort). The mean follow-up time of this study cohort was 30 mo (range, 1-127 mo). Calculated by Kaplan-Meier method, the 5-year OS and 5-year CSS rates were 27.0% and 41.3%, as shown in Figure 2.

| Variable | No. of patients (%) | HR | 95%CI | P value |

| Sex | 0.488 | |||

| Female | 28 (10.8) | Reference | ||

| Male | 231 (89.2) | 1.199 | 0.717-2.006 | 0.488 |

| Age, yr | 0.776 | |||

| ≤ 60 | 88 (34.0) | Reference | ||

| 61-70 | 112 (43.2) | 0.942 | 0.671-1.322 | 0.728 |

| ≥ 71 | 59 (22.8) | 1.082 | 0.729-1.606 | 0.695 |

| Marital status | 0.152 | |||

| Married | 187 (72.2) | Reference | ||

| Single | 57 (22.0) | 1.400 | 0.996-1.968 | 0.053 |

| Unknown | 15 (5.8) | 1.151 | 0.584-2.266 | 0.685 |

| Insurance | 0.005 | |||

| Insured | 217 (83.8) | Reference | ||

| Uninsured | 4 (1.5) | 5.272 | 1.904-14.599 | 0.001 |

| Unknown | 38 (14.7) | 0.918 | 0.608-1.358 | 0.683 |

| Race | 0.087 | |||

| Hispanic (all races) | 19 (7.3) | Reference | ||

| Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native | 2 (0.8) | 0.358 | 0.046-2.762 | 0.324 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander | 5 (1.9) | 1.229 | 0.395-3.818 | 0.722 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 10 (3.9) | 2.293 | 0.987-5.326 | 0.054 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 223 (86.1) | 0.962 | 0.534-1.734 | 0.898 |

| Grade | 0.136 | |||

| I + II | 12 (4.6) | Reference | ||

| III + IV | 214 (82.6) | 0.978 | 0.499-1.918 | 0.949 |

| Unknown | 33 (12.7) | 0.595 | 0.267-1.326 | 0.204 |

| TNM stage | 0.000 | |||

| I | 34 (13.1) | Reference | ||

| II | 59 (22.8) | 1.919 | 1.031-3.573 | 0.040 |

| III | 130 (50.2) | 2.931 | 1.662-5.168 | 0.000 |

| IV | 36 (13.9) | 4.936 | 2.610-9.334 | 0.000 |

| T stage | 0.048 | |||

| T1 | 51 (19.7) | Reference | ||

| T2 | 30 (11.6) | 1.757 | 0.992-3.112 | 0.053 |

| T3 | 164 (63.3) | 1.705 | 1.120-2.596 | 0.013 |

| T4 | 14 (5.4) | 2.334 | 1.121-4.861 | 0.024 |

| N stage | 0.000 | |||

| N0 | 86 (33.2) | Reference | ||

| N1 | 100 (38.6) | 1.841 | 1.263-2.682 | 0.001 |

| N2 | 47 (18.1) | 2.666 | 1.697-4.189 | 0.000 |

| N3 | 26 (10) | 3.836 | 2.316-6.353 | 0.000 |

| M stage | 0.058 | |||

| M0 | 246 (95) | Reference | ||

| M1 | 13 (5.0) | 1.809 | 0.981-3.337 | 0.058 |

| LODDS | 0.000 | |||

| LODDS1 (4.55 ≤ LODDS ≤ 1.90) | 134 (51.7) | Reference | ||

| LODDS2 (1.89 ≤ LODDS ≤ 0.15) | 99 (38.2) | 1.864 | 1.353-2.569 | 0.000 |

| LODDS3 (0.16 ≤ LODDS ≤ 4.27) | 26 (10) | 4.204 | 2.656-6.655 | 0.000 |

| Radiation therapy | 0.085 | |||

| No radiation and/or cancer-directed surgery | 67 (25.9) | Reference | ||

| Radiation prior to surgery | 162 (62.5) | 1.010 | 0.710-1.435 | 0.958 |

| Radiation after surgery | 25 (9.7) | 1.779 | 1.061-2.983 | 0.029 |

| Radiation before and after surgery | 5 (1.9) | 1.672 | 0.516-5.421 | 0.392 |

| Chemotherapy | 0.719 | |||

| No or unknown | 49 (18.9) | Reference | ||

| Yes | 210 (81.1) | 1.073 | 0.730-1.578 | 0.719 |

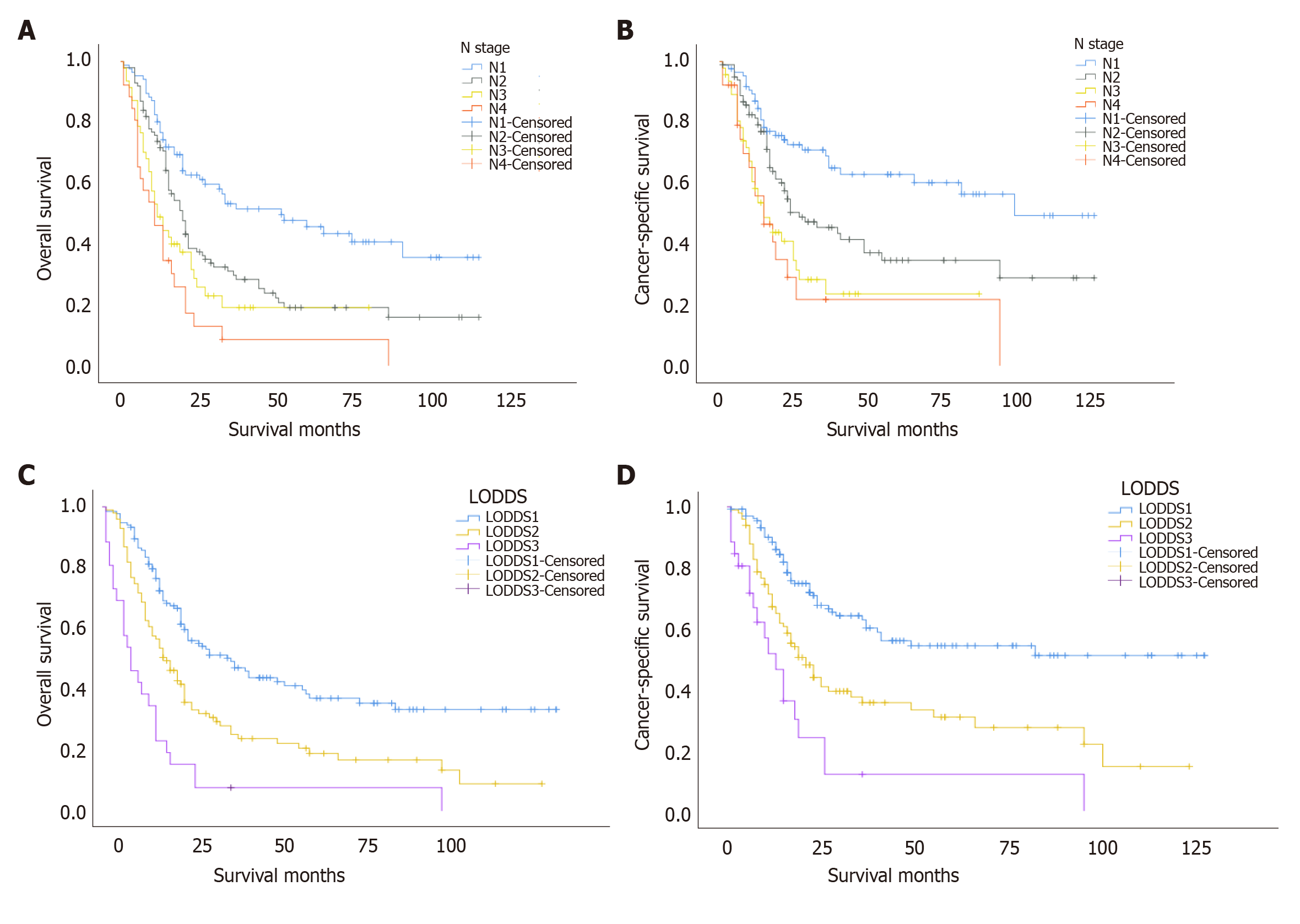

In the study cohort, the Kaplan-Meier survival curves drawn with the N stage and LODDS categories as univariates are shown in Figure 3. The analysis showed that OS and CSS decreased with the increasing N stage (log rank chi-squared score: OS: 36.215, P < 0.001, CSS: 31.583, P < 0.001; Figure 3 A and B). For LODDS, we observed that the LODDS category increased with decreasing OS and CSS (log rank chi-squared score: OS: 46.162, P < 0.001, CSS: 41.178, P < 0.001; Figure 3 C and D). The log rank chi-squared score of LODDS category was higher (OS: 46.162, CSS: 41.178) than that of N stage (OS: 36.215, CSS: 31.583).

The results of Cox regression univariate analysis for each variable in the study cohort are shown in Table 1. Univariate analyses showed that insurance, race, radiation therapy, T stage, N stage, M stage, TNM stage, and LODDS were potential prognostic factors for OS (P < 0.1). Afterwards, Cox multivariate analyses were conducted to estimate N stage (Model 1) and LODDS (Model 2). As shown in Table 2, LODDS in Model 2 was an independent prognostic factor for oesophageal SRC carcinoma patients after surgical resection (P < 0.05). Conversely, the P value of N stage in Model 1 was 0.122; thus, N stage was not a statistically significant prognostic factor in Model 1.

| Variable | Model 1 (N stage) | Model 2 (LODDS) | ||

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Insurance | 0.008 | 0.100 | ||

| Insured | Reference | Reference | ||

| Uninsured | 5.170 (1.817-14.711) | 0.002 | 3.045 (1.031-8.992) | 0.044 |

| Unknown | 0.921 (0.602-1.409) | 0.705 | 0.871 (0.570-1.331) | 0.525 |

| Race | 0.169 | 0.189 | ||

| Hispanic (all races) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.537 (0.067-4.315) | 0.559 | 0.441 (0.054-3.577) | 0.443 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander | 2.286 (0.699-7.476) | 0.171 | 2.972 (0.896-9.864) | 0.075 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 2.554 (1.062-6.144) | 0.036 | 2.255 (0.900-5.649) | 0.083 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1.334 (0.705-2.521) | 0.376 | 1.486 (0.786-2.811) | 0.223 |

| TNM stage | 0.486 | 0.030 | ||

| I | Reference | Reference | ||

| II | 1.776 (0.739-4.272) | 0.199 | 2.549 (1.141-5.695) | 0.023 |

| III | 1.527 (0.399-5.852) | 0.537 | 3.466 (1.518-7.917) | 0.003 |

| IV | 1.270 (0.173-9.334) | 0.814 | 3.479 (1.197-10.112) | 0.022 |

| T stage | 0.460 | 0.402 | ||

| T1 | Reference | Reference | ||

| T2 | 1.472 (0.644-3.362) | 0.359 | 1.013 (0.493-2.085) | 0.971 |

| T3 | 1.063 (0.494-2.291) | 0.875 | 0.699 (0.370-1.321) | 0.270 |

| T4 | 1.580 (0.521-4.797) | 0.419 | 0.900 (0.372-2.178) | 0.815 |

| N stage | 0.122 | |||

| N0 | Reference | |||

| N1 | 1.759 (0.810-3.817) | 0.153 | ||

| N2 | 2.415 (1.029-5.665) | 0.043 | ||

| N3 | 4.572 (1.044-20.021) | 0.044 | ||

| M stage | 0.304 | 0.523 | ||

| M0 | Reference | Reference | ||

| M1 | 2.027 (0.527-7.799) | 0.304 | 1.354 (0.534-3.433) | 0.523 |

| LODDS | 0.001 | |||

| 4.55 ≤ LODDS ≤ 1.90 | Reference | |||

| 1.89 ≤ LODDS ≤ 0.15 | 1.742 (1.223-2.483) | 0.002 | ||

| 0.16 ≤ LODDS ≤ 4.27 | 3.390 (1.620-7.093) | 0.001 | ||

| Radiation therapy | 0.305 | 0.389 | ||

| No radiation and/or cancer-directed surgery | Reference | Reference | ||

| Radiation prior to surgery | 0.756 (0.503-1.134) | 0.176 | 0.771 (0.515-1.153) | 0.205 |

| Radiation after surgery | 1.037 (0.571-1.883) | 0.906 | 0.998 (0.557-1.787) | 0.994 |

| Radiation before and after surgery | 1.540 (0.455-5.218) | 0.488 | 1.491 (0.444-5.008) | 0.518 |

As shown in the Table 3, Model 2 (LODDS) showed better goodness of fit and discriminatory power than Model 1 (N stage) for all patients (LODDS vs N stage, AIC 1688.824 vs 1697.519, P < 0.001, Harell’s C-index 0.673 vs 0.656, P < 0.001).

| Model | C-Index | P value | AIC | P value |

| Model 1 (N stage) | 0.656 | < 0.001 | 1697.519 | < 0.001 |

| Model 2 (LODDS) | 0.673 | < 0.001 | 1688.824 | < 0.001 |

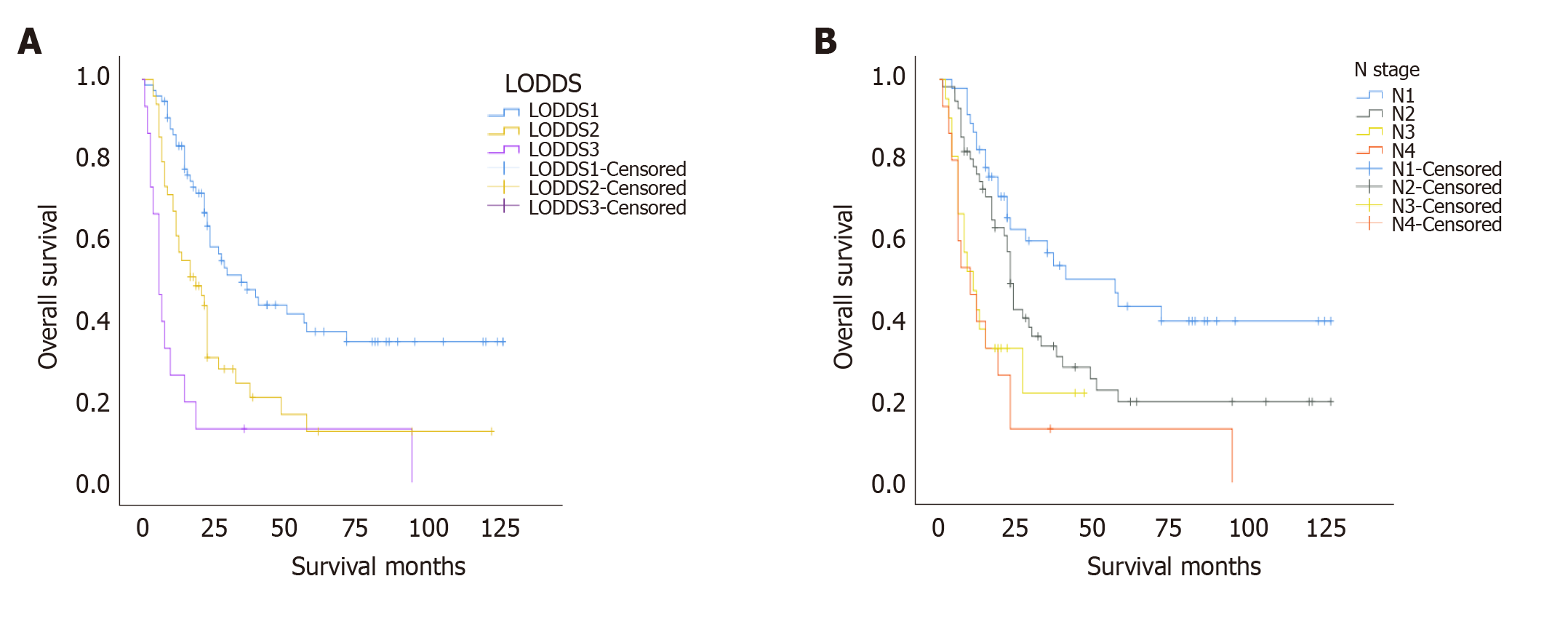

Variables in the validation cohort included sex, age, marital status, grade, T stage, N stage, M stage, total number of lymph nodes dissected, number of positive lymph nodes, chemotherapy, survival time, and survival status. LODDS, age, grade, and marital status grouping criteria were consistent with previous criteria. In the validation cohort, the Kaplan-Meier curves of overall survival with the N stage and LODDS categories are shown in Figure 4. It can be seen that OS decreased with the increasing N stage and LODDS. The log rank chi-squared score of LODDS category was higher (29.593 vs 22.830). Cox proportional hazards model was applied to perform univariate analysis of each variable. The result showed that only N and LODDS had P values less than 0.1. The AIC and Harell’s C-index of the two univariate models are shown in Table 4. LODDS showed better goodness of fit and discriminatory power than N stage in the validation cohort (LODDS vs N stage, AIC 766.830 vs 770.094 Harell's C-index 0.654 vs 0.648).

| Variable | C-Index | P value | AIC | P value |

| N stage | 0.648 | 0.030 | 770.094 | < 0.001 |

| LODDS | 0.654 | 0.029 | 766.830 | < 0.001 |

In this study, prognostic analyses of oesophageal SRC carcinoma patients after surgery in the SEER database were performed. We found that LODDS was a better predictor than the current N stage system for prognosis in patients with SRC carcinoma of the oesophagus. Validation in the external data yielded the same result.

Oesophageal SRC carcinoma has a poor prognosis. Many studies have shown that in adenocarcinomas, the presence of SRC indicates poorer clinical outcomes[22-27]. In this study, more patients with SRC carcinoma had pathological grade III-IV disease, and the TNM stage was III-IV. This finding suggests that, like other SRC cancers, oesophageal SRC carcinoma also has a high degree of malignancy, which is consistent with the conclusions of most previous SRC studies in the other types of cancer.

LODDS is a better lymph node-related prognostic indicator than N stage. As a traditional staging system related to lymph nodes, N stage is the most commonly used method to predict the prognosis of cancer patients based on the number of metastatic lymph nodes. However, it also has limitations, such as the stage migration phenomenon, which occurs when no enough lymph nodes are properly dissected[11]. As a novel assessment method based on lymph nodes, LODDS takes into account both the number of metastatic lymph nodes and the total number of harvested lymph node. At the same time, for patients without positive lymph nodes but with different total numbers of lymph nodes dissected, LODDS has a certain degree of differentiation for them, which is also theoretically better than N stage. In many studies, LODDS has been shown to be advantageous as a novel prognostic factor in many other types of cancer[14-16,18,28-30]. Few studies have found this to be controversial[31]. However, whether LODDS is also a better prognostic indicator for oesophageal SRC carcinoma has not been studied. In our research, after we performed Kaplan-Meier survival analyses of OS and CSS stratified by N stage and LODDS, the log rank chi-squared score of LODDS was higher (OS: 46.162 vs 36.215, CSS: 41.178 vs 31.583). After multivariate Cox regression analyses of LODDS and N stages, LODDS was still an independent prognostic factor, while N stage was not (Table 2). We also noted that the multivariate prediction model constructed based on LODDS has better goodness of fit and discriminatory power than the model constructed based on N stage, as shown in Table 3. In the subsequent external validation, we reached the same conclusion that LODDS is a better prognostic factor than N stage. Consequently, we conclude that LODDS may be a better prognostic factor than N stage in patients with oesophageal SRC carcinoma after surgical resection. Our study confirmed the predictive value of LODDS for the prognosis of oesophageal SRC carcinoma.

This study is designed to compare the predictive value of LODDS with N stage in the prediction of OS for patients with oesophageal SCR carcinoma after surgery. The study also has its limitations. First, as a retrospective study, selection bias is inevitable. Second, in the SEER database, the scheme of radiotherapy programs, chemotherapy regimens, detailed surgical approach, comorbidities, and other meaningful information on prognosis are not given. These will have a certain impact on the research conclusion. Third, due to the low incidence of the disease, the number of cases that can be included in the analysis is small and it is expected that in the future, prospective multi-centre, large-sample studies will further confirm the conclusion. In the future, there will be more studies on oesophageal SRC cancer, and the treatment and diagnosis of this cancer will be continuously improved.

For patients with oesophageal SRC carcinoma who underwent surgery, LODDS has superior prognostic efficacy over the N stage for estimating OS. Therefore, LODDS could be a superior prognostic factor for patients with SRC carcinoma after oesophagectomy compared with N stage.

Oesophageal signet ring cell carcinoma is a rare type of cancer, and log odds of positive lymph nodes (LODDS) may be a better prognostic factor for it.

To investigate the predictive value of LODDS for signet ring cell carcinoma of the oesophagus.

To explore whether LODDS is a better prognostic factor than N stage for oesophageal signet ring cell carcinoma.

The prognostic values of LODDS and N stage for oesophageal signet ring cell carcinoma were evaluated by univariate and multivariate analyses. The Akaike information criterion and Harrell’s C-index were used to compare the predictive value of the model. External validation was performed to further confirm the conclusion.

The multivariate Cox regression model showed that LODDS was a significant independent prognostic factor for oesophageal signet ring carcinoma patients. LODDS has better predictive value than N stage. The results of external validation were consistent with those in the study cohort.

LODDS is a superior prognostic factor for patients with oesophageal signet ring cell carcinoma after oesophagectomy than N stage.

In the future, it is expected that there will be more studies on oesophageal signet ring cell cancer, and the treatment and diagnosis of this cancer will be continuously improved.

The authors acknowledge the tremendous effort made by the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database program to create the SEER database.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Chinese Medical Doctor Association, No. 4674.

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Teramoto-Matsubara OT S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Wang LYT

| 1. | Berenson MM, Riddell RH, Skinner DB, Freston JW. Malignant transformation of esophageal columnar epithelium. Cancer. 1978;41:554-561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Enlow JM, Denlinger CE, Stroud MR, Ralston JS, Reed CE. Adenocarcinoma of the esophagus with signet ring cell features portends a poor prognosis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96:1927-1932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yendamuri S, Huang M, Malhotra U, Warren GW, Bogner PN, Nwogu CE, Groman A, Demmy TL. Prognostic implications of signet ring cell histology in esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2013;119:3156-3161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nafteux PR, Lerut TE, Villeneuve PJ, Dhaenens JM, De Hertogh G, Moons J, Coosemans WJ, Van Veer HG, De Leyn PR. Signet ring cells in esophageal and gastroesophageal junction carcinomas have a more aggressive biological behavior. Ann Surg. 2014;260:1023-1029. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sheibani K, Battifora H. Signet-ring cell melanoma. A rare morphologic variant of malignant melanoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988;12:28-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Guerrero-Medrano J, Delgado R, Albores-Saavedra J. Signet-ring sinus histiocytosis: a reactive disorder that mimics metastatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 1997;80:277-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jass JR, Sobin LH, Watanabe H. The World Health Organization's histologic classification of gastrointestinal tumors. A commentary on the second edition. Cancer. 1990;66:2162-2167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Humar B, Blair V, Charlton A, More H, Martin I, Guilford P. E-cadherin deficiency initiates gastric signet-ring cell carcinoma in mice and man. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2050-2056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rice TW, Ishwaran H, Ferguson MK, Blackstone EH, Goldstraw P. Cancer of the Esophagus and Esophagogastric Junction: An Eighth Edition Staging Primer. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12:36-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 488] [Article Influence: 54.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Twine CP, Lewis WG, Morgan MA, Chan D, Clark GW, Havard T, Crosby TD, Roberts SA, Williams GT. The assessment of prognosis of surgically resected oesophageal cancer is dependent on the number of lymph nodes examined pathologically. Histopathology. 2009;55:46-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kong SH, Lee HJ, Ahn HS, Kim JW, Kim WH, Lee KU, Yang HK. Stage migration effect on survival in gastric cancer surgery with extended lymphadenectomy: the reappraisal of positive lymph node ratio as a proper N-staging. Ann Surg. 2012;255:50-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mariette C, Piessen G, Briez N, Triboulet JP. The number of metastatic lymph nodes and the ratio between metastatic and examined lymph nodes are independent prognostic factors in esophageal cancer regardless of neoadjuvant chemoradiation or lymphadenectomy extent. Ann Surg. 2008;247:365-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 289] [Cited by in RCA: 330] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tan Z, Ma G, Yang H, Zhang L, Rong T, Lin P. Can lymph node ratio replace pn categories in the tumor-node-metastasis classification system for esophageal cancer? J Thorac Oncol. 2014; 9:1214-1221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chen LJ, Chung KP, Chang YJ, Chang YJ. Ratio and log odds of positive lymph nodes in breast cancer patients with mastectomy. Surg Oncol. 2015;24:239-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cao J, Yuan P, Ma H, Ye P, Wang Y, Yuan X, Bao F, Lv W, Hu J. Log Odds of Positive Lymph Nodes Predicts Survival in Patients After Resection for Esophageal Cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;102:424-432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Huang B, Ni M, Chen C, Cai G, Cai S. LODDS is superior to lymph node ratio for the prognosis of node-positive rectal cancer patients treated with preoperative radiotherapy. Tumori. 2017;103:87-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Xu J, Cao J, Wang L, Wang Z, Wang Y, Wu Y, Lv W, Hu J. Prognostic performance of three lymph node staging schemes for patients with Siewert type II adenocarcinoma of esophagogastric junction. Sci Rep. 2017;7:10123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Deng W, Xu T, Wang Y, Xu Y, Yang P, Gomez D, Liao Z. Log odds of positive lymph nodes may predict survival benefit in patients with node-positive non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2018;122:60-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Arrington AK, Price ET, Golisch K, Riall TS. Pancreatic Cancer Lymph Node Resection Revisited: A Novel Calculation of Number of Lymph Nodes Required. J Am Coll Surg. 2019;228:662-669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Jin S, Wang B, Zhu Y, Dai W, Xu P, Yang C, Shen Y, Ye D. Log Odds Could Better Predict Survival in Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer Patients Compared with pN and Lymph Node Ratio. J Cancer. 2019;10:249-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Vinh-Hung V, Verschraegen C, Promish DI, Cserni G, Van de Steene J, Tai P, Vlastos G, Voordeckers M, Storme G, Royce M. Ratios of involved nodes in early breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6:R680-R688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Mizushima T, Nomura M, Fujii M, Akamatsu H, Mizuno H, Tominaga H, Hasegawa J, Nakajima K, Yasumasa K, Yoshikawa M, Nishida T. Primary colorectal signet-ring cell carcinoma: clinicopathological features and postoperative survival. Surg Today. 2010;40:234-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Pernot S, Voron T, Perkins G, Lagorce-Pages C, Berger A, Taieb J. Signet-ring cell carcinoma of the stomach: Impact on prognosis and specific therapeutic challenge. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:11428-11438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 229] [Article Influence: 22.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 24. | Chrysanthos NV, Nezi V, Zafiropoulou R, Papatheodoridis G, Manesis E. Metastatic Signet-Ring Cell Carcinoma of the Skin. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:1427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wu SG, Chen XT, Zhang WW, Sun JY, Li FY, He ZY, Pei XQ, Lin Q. Survival in signet ring cell carcinoma varies based on primary tumor location: a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database analysis. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;12:209-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | El Hussein S, Khader SN. Primary signet ring cell carcinoma of the pancreas: Cytopathology review of a rare entity. Diagn Cytopathol. 2019;47:1314-1320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Shojamanesh H, Melgoza F, Pan D. Esophageal Pneumatosis and Signet Ring Cell Colon Carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:1415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Yang M, Zhang H, Ma Z, Gong L, Chen C, Ren P, Shang X, Tang P, Jiang H, Yu Z. Log odds of positive lymph nodes is a novel prognostic indicator for advanced ESCC after surgical resection. J Thorac Dis. 2017;9:1182-1189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Han L, Mo S, Xiang W, Li Q, Wang R, Xu Y, Dai W, Cai G. Prognostic accuracy of different lymph node staging system in predicting overall survival in stage IV colon cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2020;35:317-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Jin S, Wang J, Shen Y, Gan H, Xu P, Wei Y, Wei J, Wu J, Wang B, Wang J, Yang C, Zhu Y, Ye D. Comparison of different lymph node staging schemes in prostate cancer patients with lymph node metastasis. Int Urol Nephrol. 2020;52:87-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Bao X, Chen F, Qiu Y, Shi B, Lin L, He B. Log Odds of Positive Lymph Nodes is Not Superior to the Number of Positive Lymph Nodes in Predicting Overall Survival in Patients with Oral Squamous Cell Carcinomas. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;78:305-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |