Published online May 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i9.1735

Peer-review started: January 13, 2020

First decision: February 26, 2020

Revised: March 27, 2020

Accepted: April 18, 2020

Article in press: April 18, 2020

Published online: May 6, 2020

Processing time: 108 Days and 6.6 Hours

Mesonephric adenocarcinoma (MNA) of the female reproductive system is a rare tumor arising from remnants of the mesonephric duct, which is mainly located in the cervix. MNA often occurs in adult women. Due to the rarity of the disease and few reports, the specific clinical features have not been established.

We present a case of a cervical MNA in a 48-year-old woman with an incidental intra-operative diagnosis who received postoperative chemotherapy. Rare lung metastases were detected during follow-up. The existing literature is reviewed.

The clinical manifestations, pathological characteristics, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of MNA have been summarized through the review of the existing literature and the case in this paper. Due to the rarity of this disease, it is very important for the research of MNA in the future.

Core tip: We evaluated a case of cervical mesonephric adenocarcinoma in a 48-year-old female who was accidentally found by surgery and received postoperative chemotherapy. Rare lung metastases appeared during follow-up. The disease is very rare and there have been only 48 cases reported in the literature since 1962. We performed a literature review to summarize the clinical manifestation, pathological characteristics, immunohistochemistry, treatment, and prognosis of the disease, in order to increase the experience of diagnosis and treatment and benefit patients.

- Citation: Jiang LL, Tong DM, Feng ZY, Liu KR. Mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix with rare lung metastases: A case report and review of the literature. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(9): 1735-1744

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i9/1735.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i9.1735

In early embryologic development, the mesonephric ducts play a pivotal role in the sexual differentiation. The mesonephric ducts give rise to the internal genitalia, including the epididymis, the vasa deferentia, the seminal vesicles, and the ejaculatory ducts in males. In females, in the absence of testis, the mesonephric ducts regress with some remnants persisting in the broad ligament, mesosalpinx, hilus ovarii, cervix, and vagina, but have no known function[1,2]. Mesonephric adenocarcinoma (MNA) is considered to be the malignant transformation of mesonephric remnants and occurs in the distribution of mesonephric remnants (most common in the cervix)[3]. Studies have shown that MNA occurs most often in adult women. The most frequent presenting symptom is abnormal vaginal bleeding, often with a visible cervical lesion[4]. Only 48 MNAs have been reported in the literature, including the present case (Table 1); however, cases with pulmonary metastases are rare. We report a 48-year-old woman in whom an MNA was incidentally detected intra-operatively and she received postoperative chemotherapy. Rare lung metastases arose during follow-up. In addition, we performed a review of the existing literature.

| Ref. | Age | Clinical presentation | Surgery | Stage | Adjuvant therapy | Site, recurrence time, and treatment | Outcome |

| McGee et al[27], 1962 | 38 | Postcoital vaginal bleeding | Uter | IB | No | Pelvis, 6 yr, NFT | DOD: 7 yr |

| Buntine[28], 1979 | 48 | “Fibroids” | Uter + BAR | ? | No | Vagina, 7 yr, RT | DOD: 9 yr |

| Valente et al[29], 1987 | 58 | Postmenopausal vaginal bleeding | RAU + BAR + LE | IB | No | Pelvis and sacrum, 2 yr, RT | DOD: 2 yr 10 mo |

| Lang et al[30], 1990 | 46 | Cervical polyp | Uter | ? | RT | NA | DFS: 10 mo |

| 55 | None | Uter | IB | ? | ? | ? | |

| Ferry et al[2], 1990 | 55 | Pelvic relaxation | Uter + BAR | / | RT | / | DFS: 5 yr |

| Stewart et al[31], 1993 | 37 | Menometro-rrhagia | RAU + BAR + LE | IB1 | No | NA | DFS: 10 yr |

| Clement et al[3], 1995 | 46 | Menorrhagia, “fibroid uterus” | Uter + BAR + LE | IB | ? | NA | DFS: 2 yr |

| 34 | Menometro-rrhagia | Uter + BAR + LE | IB | ? | Abdomen, 1 yr, CT | DFS: 2 yr | |

| 71 | AC on Pap smear, pelvic mass | Uter + BAR + LE | IB | RT | Abdomen, 4.5 mo, CT | DOD: 8.5 mo | |

| 67 | Vaginal bleeding, cervical mass, enlarged uterus | Uter + BAR + LE | IB | ? | ? | ? | |

| 37 | Postcoital bleeding | Uter + BAR + LE | IB | CT | Abdomen, 9 and 11 yr, chemotherapy | LWD: 13 yr | |

| 73 | Vaginal bleeding | Uter + BAR | IB | RT | NA | DFS: 3 yr | |

| 40 | Menorrhagia, cervical polyp | Uter + BAR | IB | RT | NA | DFS: 2.3 yr | |

| 39 | Menorrhagia, cervical “fibroid” | Uter + BAR | IB | No | ? | ? | |

| Silver et al[24], 2001 | 62 | Postmenopausal bleeding | Uter + UAR | IB | No | NA | DFS: 1.5 yr |

| 47 | Uterine prolapse | Uter + BAR | IB | No | NA | DFS: 2.1 yr | |

| 40 | SIL (squamous intraepithelial lesion) on Pap smear | Uter + BAR | IB | No | NA | DFS: 3.2 yr | |

| 54 | Postmenopausal bleeding | Uter + BAR + LE | IB | No | NA | DFS: 6.1 yr | |

| 67 | Postmenopausal bleeding | Uter + BAR | IB | No | NA | DFS: 8.3 yr | |

| 72 | Atypical glandular cells on Pap smear | Uter + BAR + LE | IB | RT | Rectovaginal septum, 1.7 yr, CT | DFS: 2.5 yr | |

| 39 | Menorrhagia, cervical “fibroid” | Uter + BAR | IB | RT | Mediastinal metastasis and malignant pleural effusion, 5.6 yr, CT | DOD: 6.2 yr | |

| 62 | Postmenopausal bleeding | Uter + BAR + LE | IB | No | ? | ? | |

| 56 | Right ovarian cystadenoma | Uter + BAR | ? | No | NA | DFS: 7.4 yr | |

| 35 | Vaginal bleeding, pelvic pain | Biopsy of cervicovaginal mass | IIB | RT | Pelvis, 2.2 yr, CT | DOD: 3.2 yr | |

| 43 | Metrorrhagia, anemia | Uter + BAR + LE + OE | IVB | CT | Bladder and pelvis, 8 mo, RT | DOD: 10 mo | |

| Angeles et al[32], 2004 | 47 | Menometro-rrhagia, pelvic pain | Uter + BAR | IIA | RT | NA | DFS: 1 yr |

| Bagué et al[25], 2004 | 41 | Abnormal vaginal bleeding | Uter + BAR + LE + AE | IB | RT | NA | DFS: 11.4 yr |

| 24 | ? | ? | IIA | ? | ? | ? | |

| 45 | Postcoitum methrorragia | Uter + UAR | IB | NO | NA | DFS: 3.1 yr | |

| 54 | Vaginal bleeding | Uter + BAR + LE + OE | IIA | No | Bowel obstruction | DOD: 7 mo | |

| 62 | ? | Uter + BAR | IVB | CRT | Bone | LWD: 3.3 yr | |

| 54 | ? | Uter + BAR + LE + OE | IB1 | No | NA | DFS: 13 mo | |

| Yap et al[16], 2006 | 54 | Postmenopausal vaginal bleeding | Uter + BAR + LE + AE | IB1 | RT | NA | DFS: 3.1 yr |

| Fukunaga et al[33], 2008 | 46 | Abnormal vaginal bleeding | Uter + BAR + LE + OE | IB | NO | NA | DFS: 4 mo |

| Anagno-stopoulos et al[5], 2012 | 64 | Asymptomatic | RAU + BAR + LE | IB1 | NO | NA | DFS: 6 mo |

| Nomoto et al[34], 2012 | 64 | Postmenopausal vaginal bleeding | Uter + BAR + LE | IB2 | No | Multifocal lung metastases, 1 yr, CT | ? |

| 64 | Postmenopausal vaginal bleeding | Uter + BAR + LE | IB1 | No | NA | ? | |

| Abdul-Ghafar et al[35], 2013 | 48 | Uterine mass | Vaginal uter | IB1 | CRT | NA | DFS: 2 yr |

| Meguro et al[36], 2013 | 63 | Postmenopausal vaginal bleeding | RAU + BAR + LE | IIA | No | Local R (7 mo), CRT | DFS: 7 mo |

| Menon et al[13], 2013 | 65 | Postmenopausal bleeding | Uter + BAR + LE | IB1 | RT | NA | DFS: 6 mo |

| Roma[37], 2014 | 65 | Postmenopausal bleeding | Uter + BAR | IB1 | CT | Recent case | Recent case |

| Dierickx et al[4], 2016 | 66 | Postmenopausal vaginal bleeding | CRT + Uter + BAR + LE | IIB | No | NA | DFS: 2 yr |

| Kır et al[38], 2016 | 53 | ? | RAU + BAR + LE + AE | IB | ? | ? | ? |

| Yeo et al[39], 2016 | 55 | Metastatic pulmonary nodules | ? | IV | ? | ? | ? |

| Cavalcanti et al[18], 2017 | 59 | Postmenopausal bleeding | RAU + BAR + LE | IB1 | ? | Pelvic, 3 mo, CRT | DOD: 14 mo |

| Papoutsis et al[40], 2019 | 67 | Postmenopausal bleeding | RAU + BAR + LE | IIB | CRT | NA | DFS: 12 mo |

| Present case | 48 | Asymptomatic | Uter + BAR + LE + OE + AE | IV | CT | Lung, 2.8 yr, CT + targeted therapy | DFS: 2.8 yr; LWD: 2 yr |

A 48-year-old gravida 2 para 1 woman was admitted to our hospital for evaluation of an enlarged right inguinal mass and right adnexal cyst on physical examination.

The patient was admitted to our hospital for evaluation of an enlarged right inguinal mass and right adnexal cyst on physical examination. The right inguinal mass was first discovered two years ago and increased gradually. The right adnexal cyst was found by physical examination at another hospital half a month ago. There was no irregular vaginal bleeding, menstrual changes, or lower abdominal pain. The cervical ThinPrep cytological test (TCT) and human papillomavirus (HPV) testing were completed in the clinic, and the results were normal.

The patient underwent hemorrhoids surgery more than 10 years ago. She denied the history of diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease.

The patient’s personal and family history was unremarkable.

Body temperature, blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, and chest examination were all normal.

The vulva developed normally, and the vaginal unobstructed. The cervical size was normal, the surface was smooth, and there was no contact bleeding. A cystic mass of 5 cm × 3 cm was palpable in the right groin and could not return when recumbent. The uterus was anterograde with an irregular shape and poor activity. A cystic mass about 4 cm in diameter, irregular in shape and not tender, was palpable in the right adnexa.

On routine laboratory testing, the serum levels of CA-125, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), CA19-9, CA724, and alpha fetoprotein were within the normal ranges.

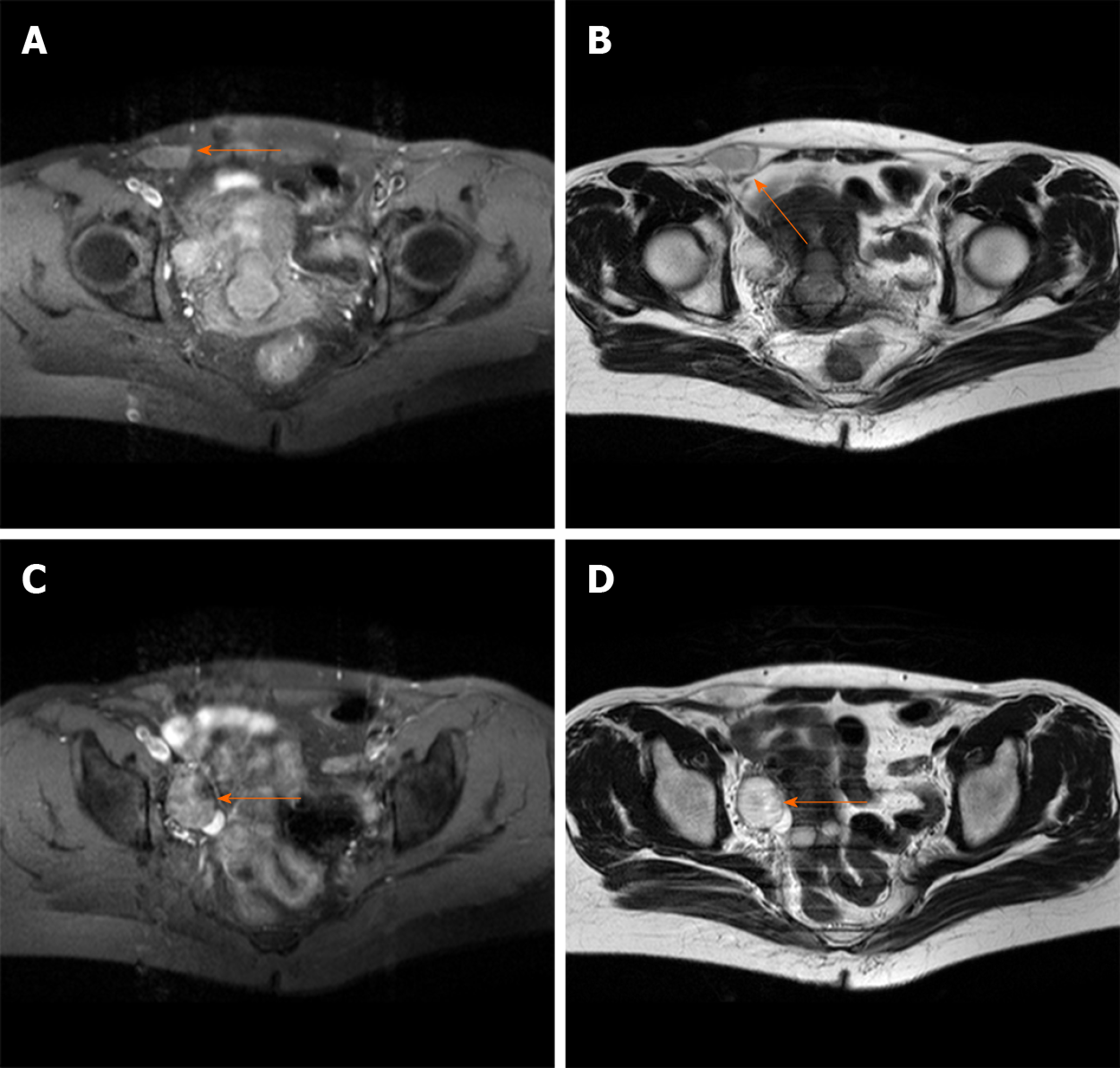

Transvaginal ultrasound revealed a cystic mass (4.3 cm × 2.3 cm) in the right adnexa and a few moderate echo clusters attached to the wall of the cystic mass, the largest of which was 0.8 cm × 0.7 cm in size. For further clarifying the diagnosis, the pelvic cavity magnetic resonance imaging examination was completed. It revealed a liquid area in the right iliac fossa (2.7 cm × 1.3 cm × 2.6 cm) (Figure 1A and B). Oval mixed signal shadows with a slightly longer T1 and T2 signal were observed in the right adnexal area, with a size of 2.6 cm × 3.0 cm and no enhancement after intensification (Figure 1C and D).

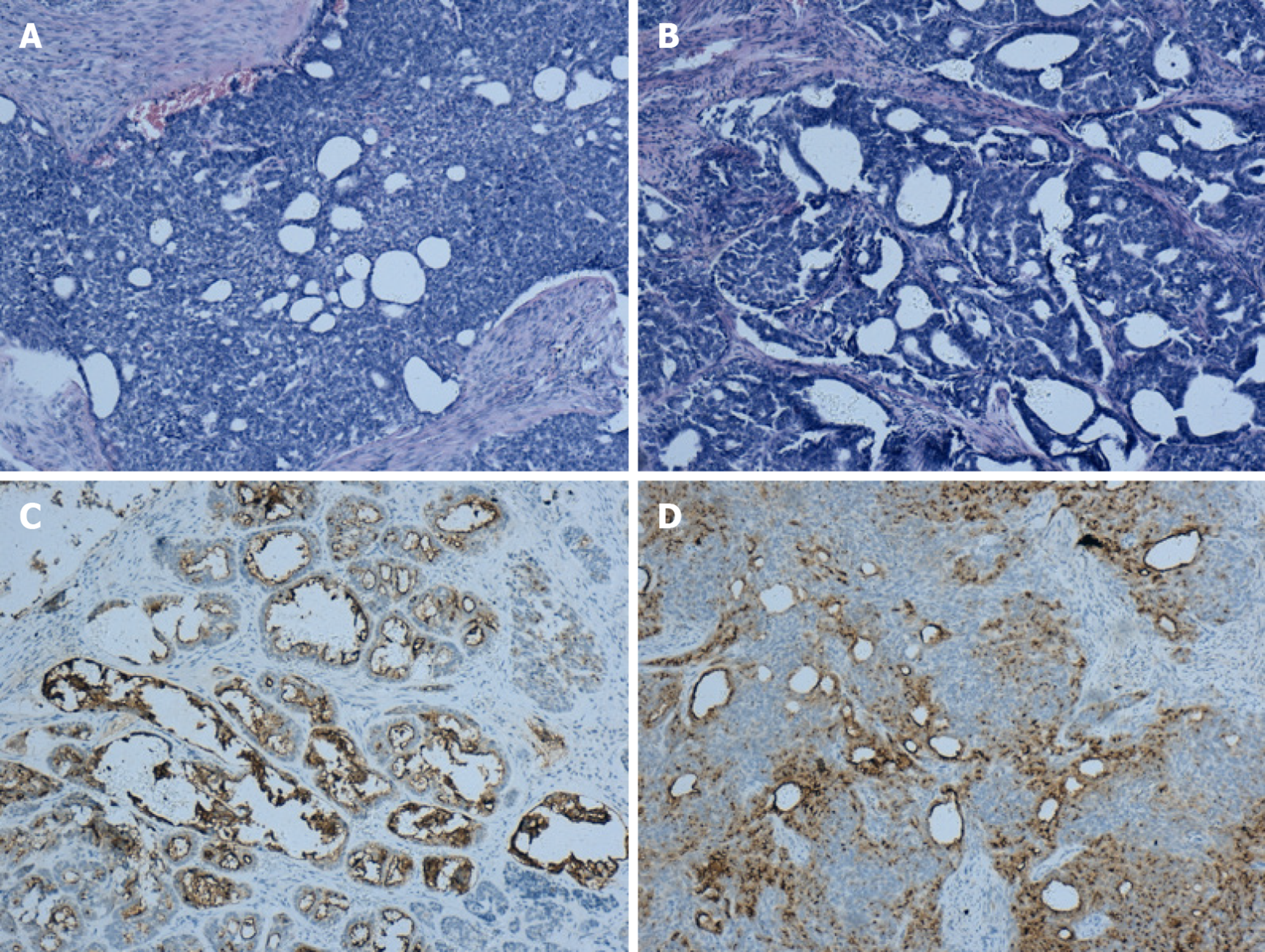

Grossly, a 4 cm × 3 cm tumor occupied the cervical canal and infiltrated the full thickness of the myometrium of the lower uterine body. The papilla in the inner wall of the right ovary was approximately 1 cm in size. Microscopically, atypical cells were seen, and the lesion infiltrated tubular and papillary structures in the cervix (Figure 2A). The tumor cells in the right ovary exhibited the same pattern of the cervix, suggesting that they may have metastasized from the cervix (Figure 2B). The immunohistochemical findings showed positive reactions in the tumor cells for CD10 (Figure 2C and D), and focal positivity for pancytokeratin (CK) and calretinin. The Ki-67 proliferation index was slightly increased. The pathological examination revealed a malignant tumor in the lower uterine segment and cervical canal (middle renal duct adenocarcinoma was considered), and right ovarian metastasis, with no lesions and metastases found in the remaining resected tissues and lymph nodes.

The final diagnosis was an MNA of the lower uterine body and cervix with right ovarian metastatic cancer.

The patient underwent an exploratory laparotomy. We noted that a 5 cm × 3 cm protuberant cyst of the right lower abdomen femoral sulcus extending to the round ligament and a cyst with an intact capsule had formed on the right ovary, approximately 4.5 cm × 3 cm in size. Thus, resection of the cyst in the right round ligament and a right adnexectomy were performed. Frozen section pathology reported a serous cystadenoma of the ovary with malignant transformation. Therefore, a hysterectomy, left salpingo-oophorectomy, pelvic lymphadenectomy, omentectomy, and appendectomy were performed. The patient received six cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy after surgery.

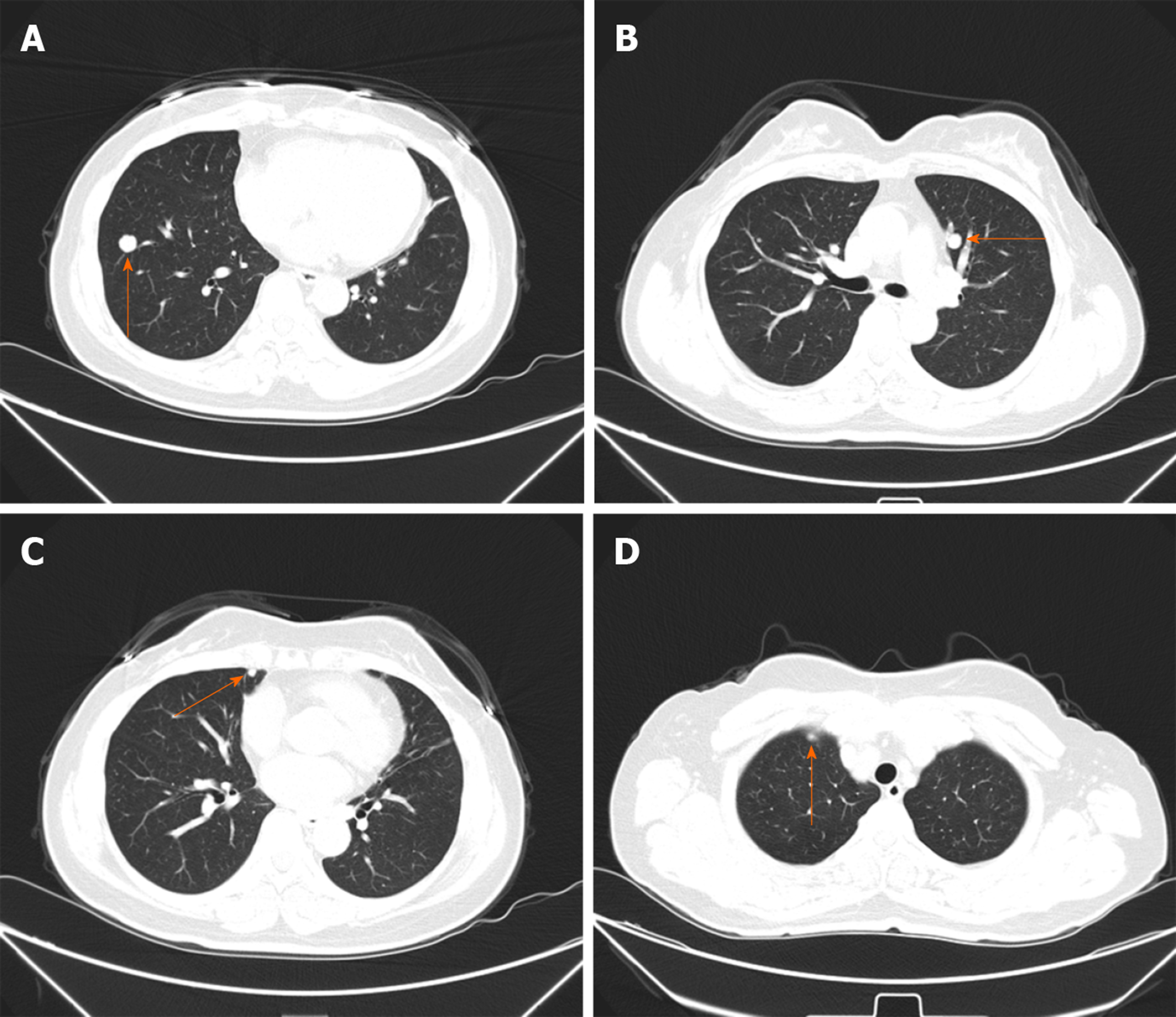

Thirty-two months later, multifocal lung nodules were found and confirmed to be metastatic lesions by puncture biopsy (Figure 3A-D). The patient underwent chemotherapy. She is currently alive and well undergoing targeted drug treatment.

In early embryologic development, the mesonephric duct (also known as the Wolffian duct) plays a key role during the sexual differentiation stage. In males, the mesonephric duct gives rise to the internal genitalia, including the epididymis, vasa deferentia, seminal vesicles, and ejaculatory ducts. In females, the mesonephric ducts regress in the absence of testosterone. The remnants persist along the following trajectory, with the most common site being the cervix: The broad ligament; mesosalpinx; hilus ovarii; cervix; and vagina[1,2]. The remnants of the mesonephric duct are often located in the lateral wall of the cervix but may also involve the entire cervix. MNA of the cervix is a rare tumor considered to be the malignant transformation of mesonephric remnants[4]. To the best of our knowledge, 48 cases of cervical MNA have been reported in the literature, including our case (Table 1).

Studies have shown that MNA most often occurs in adult females. Of the 48 cases reviewed herein, the age ranged from 24-73 years, with an average age of 52.7 years. The most common symptom of MNA is abnormal vaginal bleeding from cervical lesions[4]. Among the 48 cases (including this case), 17 had postmenopausal vaginal bleeding, 8 had menorrhagia, and 3 had postcoital vaginal bleeding initially. Other clinical manifestations include cervical masses and abnormal smears. There is a rare case of MNA which originally presented as pulmonary nodules. In addition, three cases in asymptomatic patients were detected incidentally. The patient reported herein was asymptomatic and MNA was noted intra-operatively and confirmed postoperatively. Unlike common squamous epithelial carcinoma, this type of cervical cancer is rarely discovered by cytologic testing. The age of onset is late and the incidence does not decrease with aging[5]. Cervical cancer screening is the most important method in cancer prevention. Screening tests such as the Papanicolaou test (Pap smear) and TCT reduced the incidence and increased the 5-year survival rate of cervical cancer significantly[6]. However, the accuracy of the current cervical cancer screening tests still needs to improve. In recent years, more biomarkers have shown their potentials in the screening, diagnosis, and monitoring of cervical cancer. Zheng et al[7] reported that plasma exosomal miR-30d-5p and let-7d-3p are valuable diagnostic biomarkers for non-invasive screening of cervical cancer and its precursors. Blood extraction is more convenient than TCT or Pap smear tests. They are expected to be applicated in clinical diagnosis with larger samples further[7]. The differentially expressed miRNAs and related target genes analyzed by Gao et al[8] prompted that they may be used as promising biomarker for the early screening of high-risk populations and early diagnosis of cervical cancer. In this way, we can offer better screening, diagnosis, and prognosis to the patients.

The mesonephric remnants of the cervix were first identified incidentally in total hysterectomy and cervical conization specimens; 22% of mesonephric remnants reported were in the adult cervix[2,9]. The remnants occasionally become hyperplastic, but rarely develop into MNA. Now, five categories of cervical mesonephric lesions have been described, as follows: Mesonephric remnants; lobular mesonephric hyperplasia; diffuse mesonephric hyperplasia; mesonephric ductal hyperplasia; and mesonephric carcinoma[10]. Mesonephric remnants usually present with a lobular structure. The glandular duct has no cilia and is covered by a single layer of cuboidal epithelium. Eosinophilic secretions can be noted in the lumen. In the case of mesonephric hyperplasia, the number of glandular ducts increases, which can be divided into three categories according to the microscopic morphology: Lobular hyperplasia; diffuse hyperplasia; and ductal hyperplasia. Lobular hyperplasia (lobular growth) is characterized by multiple elongated tubules embraced by lobules. In 90% of cases, hyaline material that is pink in color and periodic acid Schiff reaction-positive can be seen in the lumen. The type of diffuse hyperplasia is rare. The number of mesonephric tubes is large and scattered, which can be easily misdiagnosed as adenocarcinoma, but the epithelial cells have no atypia or mitoses. Ductal hyperplasia is a feature of large ducts (single or multiple layers of pseudo epithelium), and there are often microscopic papillary changes in the epithelium[11,12].

MNAs usually present with florid mesonephric hyperplasia and a densely eosinophilic luminal secretion[13]. Various morphologic patterns may be present, such as tubular, glandular, papillary, and reticular. MNAs show carcinomatous cell manifestations, with back-to-back arranged glands, blood vessels, and peripheral nerve infiltration. Residual mesonephric ducts around the tumor and most macroscopic mass can be seen[14]. MNA should be distinguished from florid mesonephric hyperplasia[15]. The former is rarer and MNA must be diagnosed after ruling out florid mesonephric hyperplasia. Sometimes, heteromorphic cells can be seen under the microscope, but the nuclear division does not exceed 1/10 high power fields[3,11].

In recent years, our gradual understanding and the increased number of MNA cases reflect the value of immunohistochemistry. If the morphologic diagnosis cannot be confirmed, immunohistochemistry can help further diagnose the disease. The immunochemical features of MNA include positivity for CAM5.2, CK7, and EMA, and reactivity for calretinine and CD10. CEA, CK20, estrogen receptor (ER), and progesterone receptor (PR) are usually negative[16]. The primary value of CD10 immunostaining is to support a mesonephric origin when positive in a benign cervical lesion[17]. Specifically, Cavalcanti et al[18] reported a previously unreported case of mixed MNA and high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix in which calretinin was negatively expressed. It is well-known that HPV infection is closely related to the occurrence of cervical cancer; however, p16 is negative in MNA, thus p16 is not associated with high-risk HPV infections[19]. PAX8 expression is strongly positive in both benign and malignant mesonephric lesions, while in common pathologic types of cervical adenocarcinoma, PAX8 is expressed in a variety of ways. Because PAX8 is expressed in a variety of lesion types, it is not reliable in the identification of benign and malignant cervical lesions[17]. The immunoreactivity of PAX2 appears to be absent in MNA and cervical adenocarcinoma with the least variation, but PAX2 is diffusely positive in mesonephric hyperplasia, which can be used to distinguish mesonephric hyperplasia and MNA[12]. As a transcription factor that plays an important role in the process of embryogenesis, development, and differentiation, GATA3 has been reported to be highly sensitive and specific to mesonephric lesions in the lower reproductive tract of females. GATA3 expression may be a marker of mesonephric lesions because it has been shown to be positive in all mesonephric remnants and hyperplasia and nearly all mesonephric carcinomas tested, and infrequent or absent in endocervical adenocarcinomas (usual and gastric types)[20-22].

The mixture of morphologic patterns is one of the most characteristic features of MNA. Therefore, its differential diagnoses include clear cell adenocarcinoma, endometrioid adenocarcinoma, serous adenocarcinoma, minimal deviation adenocarcinoma (malignant adenoma), and mesonephric hyperplasia[23]. The biggest challenge of diagnosis proposed in the literature is to distinguish MNA from clear cell carcinoma[10]; however, clear cell carcinomas usually present as cystic, papillary, or solid structures of varying degrees, which were previously classified as mesonephric carcinoma. Clear and nail cells are not present in mesonephric carcinoma, and there were no mesonephric remnants or hyperplasia around the tumor. Immuno-histochemical staining for ER and PR can be positive, but CD10 is negative[23]. When the MNA has an apparent ductal type, the MNA must be distinguished from endometrioid carcinoma of the cervix. If there are mesonephric remnants around the tumor and a lack of squamous cells, an MNA is likely to be diagnosed and immunohistochemical staining for ER, PR, and CEA are negative in MNA[24]. The epithelium of MNA is sometimes similar to serous carcinoma, but the nuclear atypia of serous carcinoma is more evident and there are no eosinophilic substances in the lumen. Minimal deviation adenocarcinoma (adenoma malignum) includes abnormally-shaped endocervical glands embraced by characteristic benign mucin-secreting cells, whereas in mesonephric cells the intracellular mucin is almost absent[25]. In contrast to mesonephric hyperplasia, MNA has no lobule structures and the nuclei present as a cytologic malignancy. The Ki-67 proliferation index is < 1% in hyperplasia and 15%-20% in MNA[24].

There is no explicit treatment for this rare disease. Based on the current cases described in the literature, treatment of MNA depends on its stage. The methods of operation include uterectomy with or without bilateral adnexal resection, pelvic lymphadenectomy, and adjuvant chemo- or radio-therapy[4]. Among the 48 cases retrieved in this paper (including the present case), 33 were diagnosed as stage I (69%). All stage I patients underwent total hysterectomies, and postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy was administered to 8 patients, chemotherapy administered to 2, and combined radiotherapy and chemotherapy to 1. There was no significant difference in disease-free survival time between stage I patients receiving adjuvant therapy and those without adjuvant therapy.

Due to the rarity of cervical MNA, the biological behavior and prognosis of these tumors are unclear. It has been reported that the prognosis of MNA is worse than that of other histologic types. Previous studies have shown that the recurrence rate of stage I MNA patients is 32%, while the recurrence rates of early cervical adenocarcinoma and cervical squamous cell carcinoma are 16% and 11%, respectively[4,26]. In the 48 cases reported in the literature, 15 (31.25%) had recurrences, with an average recurrence time of 2.8 years. The recurrence sites were diverse, most of which were the pelvis and abdominal cavity, and there were only two cases of lung metastasis, including the present case. Combined with previous studies, we can reasonably manage and closely follow patients with MNA of the cervix according to the current guiding principles of similar stages and pathologic results of cervical adenocarcinoma.

Combined with the cases retrieved in this paper, cervical smear examination of patients with MNA is often negative, most of which are confirmed by cervical biopsy or cone resection. The case reported herein had no cervical abnormalities, and the TCT and HPV tests were both negative. During surgery, the accessory masses were removed as planned and malignant changes were demonstrated, but the source could not be determined. Therefore, MNA with ovarian metastasis was diagnosed based on paraffin-embedded specimens postoperatively. After adjuvant treatment, rare lung metastases were detected after 2.8 years. We will continue to follow the patient. Therefore, the diagnosis is difficult. In future clinical studies, attention should be paid to the occurrence of rare cervical disease without symptoms. Continuous research should be conducted to increase the experience of diagnosis and treatment of this disease for the benefit of patients.

We thank the China Medical University for its support and the patient for permitting us to use her data to complete this article.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Laganà AS S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Shaw G, Renfree MB. Wolffian duct development. Sex Dev. 2014;8:273-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ferry JA, Scully RE. Mesonephric remnants, hyperplasia, and neoplasia in the uterine cervix. A study of 49 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990;14:1100-1111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Clement PB, Young RH, Keh P, Ostör AG, Scully RE. Malignant mesonephric neoplasms of the uterine cervix. A report of eight cases, including four with a malignant spindle cell component. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:1158-1171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Dierickx A, Göker M, Braems G, Tummers P, Van den Broecke R. Mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the cervix: Case report and literature review. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2016;17:7-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Anagnostopoulos A, Ruthven S, Kingston R. Mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix and literature review. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Smith RA, Manassaram-Baptiste D, Brooks D, Doroshenk M, Fedewa S, Saslow D, Brawley OW, Wender R. Cancer screening in the United States, 2015: a review of current American cancer society guidelines and current issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:30-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 251] [Cited by in RCA: 254] [Article Influence: 25.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zheng M, Hou L, Ma Y, Zhou L, Wang F, Cheng B, Wang W, Lu B, Liu P, Lu W, Lu Y. Exosomal let-7d-3p and miR-30d-5p as diagnostic biomarkers for non-invasive screening of cervical cancer and its precursors. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gao C, Zhou C, Zhuang J, Liu L, Liu C, Li H, Liu G, Wei J, Sun C. MicroRNA expression in cervical cancer: Novel diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119:7080-7090. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hart WR. Symposium part II: special types of adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2002;21:327-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bifulco G, Mandato VD, Mignogna C, Giampaolino P, Di Spiezio Sardo A, De Cecio R, De Rosa G, Piccoli R, Radice L, Nappi C. A case of mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the vagina with a 1-year follow-up. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18:1127-1131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Seidman JD, Tavassoli FA. Mesonephric hyperplasia of the uterine cervix: a clinicopathologic study of 51 cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1995;14:293-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Rabban JT, McAlhany S, Lerwill MF, Grenert JP, Zaloudek CJ. PAX2 distinguishes benign mesonephric and mullerian glandular lesions of the cervix from endocervical adenocarcinoma, including minimal deviation adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:137-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Menon S, Kathuria K, Deodhar K, Kerkar R. Mesonephric adenocarcinoma (endometrioid type) of endocervix with diffuse mesonephric hyperplasia involving cervical wall and myometrium: an unusual case report. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2013;56:51-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kim SS, Nam JH, Kim GE, Choi YD, Choi C, Park CS. Mesonephric Adenocarcinoma of the Uterine Corpus: A Case Report and Diagnostic Pitfall. Int J Surg Pathol. 2016;24:153-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kawauchi S, Kusuda T, Liu XP, Suehiro Y, Kaku T, Mikami Y, Takeshita M, Nakao M, Chochi Y, Sasaki K. Is lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia a cancerous precursor of minimal deviation adenocarcinoma?: a comparative molecular-genetic and immunohistochemical study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:1807-1815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yap OW, Hendrickson MR, Teng NN, Kapp DS. Mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the cervix: a case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103:1155-1158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Goyal A, Yang B. Differential patterns of PAX8, p16, and ER immunostains in mesonephric lesions and adenocarcinomas of the cervix. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2014;33:613-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cavalcanti MS, Schultheis AM, Ho C, Wang L, DeLair DF, Weigelt B, Gardner G, Lichtman SM, Hameed M, Park KJ. Mixed Mesonephric Adenocarcinoma and High-grade Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of the Uterine Cervix: Case Description of a Previously Unreported Entity With Insights Into Its Molecular Pathogenesis. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2017;36:76-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Houghton O, Jamison J, Wilson R, Carson J, McCluggage WG. p16 Immunoreactivity in unusual types of cervical adenocarcinoma does not reflect human papillomavirus infection. Histopathology. 2010;57:342-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Howitt BE, Emori MM, Drapkin R, Gaspar C, Barletta JA, Nucci MR, McCluggage WG, Oliva E, Hirsch MS. GATA3 Is a Sensitive and Specific Marker of Benign and Malignant Mesonephric Lesions in the Lower Female Genital Tract. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39:1411-1419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Roma AA, Goyal A, Yang B. Differential Expression Patterns of GATA3 in Uterine Mesonephric and Nonmesonephric Lesions. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2015;34:480-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Schwartz LE, Khani F, Bishop JA, Vang R, Epstein JI. Carcinoma of the Uterine Cervix Involving the Genitourinary Tract: A Potential Diagnostic Dilemma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:27-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Erşahin C, Huang M, Potkul RK, Hammadeh R, Salhadar A. Mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the vagina with a 3-year follow-up. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;99:757-760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Silver SA, Devouassoux-Shisheboran M, Mezzetti TP, Tavassoli FA. Mesonephric adenocarcinomas of the uterine cervix: a study of 11 cases with immunohistochemical findings. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:379-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bagué S, Rodríguez IM, Prat J. Malignant mesonephric tumors of the female genital tract: a clinicopathologic study of 9 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:601-607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Fregnani JH, Soares FA, Novik PR, Lopes A, Latorre MR. Comparison of biological behavior between early-stage adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008;136:215-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | McGee CT, Cromer DW, Greene RR. Mesonephric carcinoma of the cervix-differentiation from endocervical adenocarcinoma. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1962;84:358-366. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Buntine DW. Adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix of probable Wolffian origin. Pathology. 1979;11:713-718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Valente PT, Susin M. Cervical adenocarcinoma arising in florid mesonephric hyperplasia: report of a case with immunocytochemical studies. Gynecol Oncol. 1987;27:58-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Lang G, Dallenbach-Hellweg G. The histogenetic origin of cervical mesonephric hyperplasia and mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix studied with immunohistochemical methods. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1990;9:145-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Stewart CJ, Taggart CR, Brett F, Mutch AF. Mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix with focal endocrine cell differentiation. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1993;12:264-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Angeles RM, August CZ, Weisenberg E. Pathologic quiz case: an incidentally detected mass of the uterine cervix. Mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the cervix. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:1179-1180. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Fukunaga M, Takahashi H, Yasuda M. Mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix: a case report with immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies. Pathol Res Pract. 2008;204:671-676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Nomoto K, Hayashi S, Tsuneyama K, Hori T, Ishizawa S. Cytopathology of cervical mesonephric adenocarcinoma: a report of two cases. Cytopathology. 2013;24:129-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Abdul-Ghafar J, Chong Y, Han HD, Cha DS, Eom M. Mesonephric Adenocarcinoma of the Uterine Cervix Associated with Florid Mesonephric Hyperplasia: A Case Report. J Lifestyle Med. 2013;3:117-120. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Meguro S, Yasuda M, Shimizu M, Kurosaki A, Fujiwara K. Mesonephric adenocarcinoma with a sarcomatous component, a notable subtype of cervical carcinosarcoma: a case report and review of the literature. Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Roma AA. Mesonephric carcinosarcoma involving uterine cervix and vagina: report of 2 cases with immunohistochemical positivity For PAX2, PAX8, and GATA-3. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2014;33:624-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Kır G, Seneldir H, Kıran G. A case of mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix mimicking an endometrial clear cell carcinoma in the curettage specimen. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;36:827-829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Yeo MK, Choi SY, Kim M, Kim KH, Suh KS. Malignant mesonephric tumor of the cervix with an initial manifestation as pulmonary metastasis: case report and review of the literature. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2016;37:270-277. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Papoutsis D, Sahu B, Kelly J, Antonakou A. Perivascular epithelioid cell tumour and mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix: an unknown co-existence. Oxf Med Case Reports. 2019;2019:omy115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |