Published online May 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i9.1608

Peer-review started: February 22, 2020

First decision: March 18, 2020

Revised: March 26, 2020

Accepted: April 24, 2020

Article in press: April 24, 2020

Published online: May 6, 2020

Processing time: 67 Days and 23.4 Hours

Gastric cancer has a relatively high prevalence and is one of the most common causes of cancer-related death worldwide. However, the prognosis for gastric cancer remains poor, especially in the advanced stages, despite many improvements in diagnosis and treatment.

To evaluate the outcomes regarding advanced gastric cancer development according to sex and age.

We retrospectively reviewed 2005 patients who underwent curative gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer between 2002 and 2007 at a single Korean centre. Prognosis and risk factors for nodal involvement were evaluated according to sex and age.

In this retrospective cohort study, we examined the cases of 2005 patients [sex, 1384 men (69%), 621 women (31%)] with advanced gastric cancer. The patients’ age range was 22-87 years (mean age: 57.7 ± 12.3 years), with approximately 53.3% of the patients being ≤ 60 years old. Based on a Cox proportional hazards model, overall survival was independently predicted by older age, larger tumour size, lymphovascular invasion, lymph node metastasis, deeper tumour invasion, moderately-to-poorly differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma, and signet ring cell carcinoma. The same model revealed that relapse-free survival was independently predicted by advanced age, larger tumour size, lymphovascular invasion, deeper tumour invasion, poorly differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma, and signet ring cell carcinoma.

Among patients with advanced gastric cancer, older age independently predicted poor overall survival and relapse-free survival. However, there were no significant sex-based differences in relapse-free and overall survival.

Core tip: Understanding the association between age and the survival rate for gastric cancer might be helpful to clarify the prognostic value of age and potentially improve treatment efficacy. However, few studies have evaluated the effects of sex or age on gastric cancer outcomes, especially for advanced gastric cancer. Thus, we evaluated the relationships of age and sex with advanced gastric cancer outcomes in 2005 patients at our center.

- Citation: Alshehri A, Alanezi H, Kim BS. Prognosis factors of advanced gastric cancer according to sex and age. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(9): 1608-1619

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i9/1608.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i9.1608

Gastric cancer (GC; cardia or non-cardia types) is an important disease worldwide, with up to 1000000 new diagnosed cases in 2018 and potentially more than 783000 deaths annually. Global estimates have suggested that GC is the fifth and third most frequently diagnosed and deadly cancer, respectively, with rates being approximately two-fold higher in men than in women[1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Japanese Society of Gastroenterological Endoscopy define early gastric cancer as gastric tumours that are confined to the mucosal layer, regardless of lymph node metastasis, although the classification of advanced gastric cancer (AGC) remains a debatable issue[2]. Although most authors define AGC as tumours infiltrating beyond the submucosal layer, regardless of metastasis or N0 status, others consider T3-4 tumours to be AGC[3]. For example, AGC is considered any gastric tumour that is T2-4b/N0-3/M0-1 staged, according to the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM (AJCC TNM) system[4]. Thus, relative to early gastric cancer, AGC is defined as being locally advanced and metastatic. When curative treatment is not possible because of metastatic tumours, some patients may benefit from neoadjuvant therapy for locally advanced GC, which may allow a curative surgery performance in the future[5].

The incidence and mortality rates for resectable AGC vary among East Asian countries, which have fewer complications and deaths, and better survival rates than the Western countries. For example, the 5-year survival rate is almost 70% in Japan[6], higher to the corresponding rates of up to 25% in Europe and the United States[7]. Age is a prognostic factor for many cancers[8], and the prevalence of GC increases with age, peaking at an age of 60-70 years[9]. Thus, understanding the association between age and the survival rate for GC might be helpful to clarify the prognostic value of age and potentially improve treatment efficacy[10]. Histopathological type, depth of invasion, and tumour size are known predictors of lymph node metastasis[11] and prognosis in patients with GC[12]. Kim et al[11] also recently stated that sex was a predictor for lymph node metastasis and that the histological subtype varied according to sex and age. However, few studies have evaluated the effects of sex or age on GC outcomes, especially for AGC. Thus, we evaluated the relationships of age and sex with AGC outcomes at our centre.

We retrospectively evaluated 2005 patients who had undergone curative gastrectomy for AGC between 2002 and 2007 at the Asan Medical Center (Seoul, South Korea). The study’s retrospective protocol was approved by the institutional review board (protocol number S2019-1849-0001).

All patients had undergone extensive lymphadenectomy (D1 and greater) according to the 2018 Korean Gastric Cancer Association clinical management guidelines[12]. Macroscopic (endoscopic) findings were also analysed according to the Korean Gastric Cancer Association clinical management guidelines[13]. The WHO categorises gastric adenocarcinomas into four subtypes according to their histopathological pattern: Papillary, mucinous, tubular, and signet ring cell carcinoma (SRC)[14]. Tubular adenocarcinoma was classified as well-differentiated, moderately-differentiated, or poorly-differentiated according to the eighth edition of the AJCC TNM staging system[4]. According to the Japanese classification system, gastric adenocarcinoma was classified as differentiated (well-differentiated, moderately-differentiated, or papillary adenocarcinoma) or undifferentiated (poorly-differentiated adenocarcinoma or SRC)[15]. The patients’ characteristics, lymph node metastasis statuses, and outcomes were reviewed to identify their relationships with sex and age. Relapse-free survival (RFS) was defined as the time from tumour resection until the first instance of disease recurrence, death that was unrelated to gastric cancer, or the last follow-up without evidence of recurrence. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from tumour resection until death by any cause or the last follow-up.

Continuous data were presented as means ± SD and analysed using the Student’s t-test. Risk factors were analysed using the logistic regression model (multivariate analysis) or the Chi-squared test (univariate analysis). Survival outcomes were compared using the Kaplan-Meier method with the log-rank test (univariate analysis) or the Cox proportional hazards regression model (multivariate analysis). All analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS software (version 25.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States), and differences were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05.

The patients’ clinicopathological characteristics are summarised in Table 1. The patients’ age range was 22-87 years (mean: 57.7 ± 12.3 years), with approximately 53.3% of the patients being ≤ 60 years old. The participants were 1384 men (69%) and 621 women (31%) (total, 2005). The mean body mass index (BMI) was 23.3 ± 3.2 kg/m2 (range: 12.3-57.8 kg/m2). Approximately 30.7% of patients had comorbidities, including hypertension (22%), diabetes mellitus (10.6%), and other conditions (5.6%).

| Characteristic | |

| Age (yr) | |

| Range | 22-87 |

| mean ± SD | 57.7 ± 12.3 |

| Age grouping, n (%) | |

| ≤ 60 yr | 1069 (53.3) |

| > 60 yr | 936 (46.7) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 1384 (69) |

| Female | 621 (31) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | |

| Range | 12.3–57.8 |

| mean ± SD | 23.3 ± 3.2 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | 616 (30.7) |

| Hypertension | 441 (22) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 212 (10.6) |

| Others | 112 (5.6) |

| Tumour size (cm) | |

| Range | 1-48 |

| mean ± SD | 6.3 ± 3.5 |

| Location, n (%) | |

| Upper third | 345 (17.2) |

| Middle third | 463 (23.1) |

| Lower third | 1197 (59.7) |

| Depth of invasion, n (%) | |

| Muscularis propria | 504 (25.1) |

| Subserosal | 865 (43.1) |

| Serosa exposed or invaded | 608 (30.4) |

| Histology, n (%) | |

| Papillary adenocarcinoma | 7 (0.3) |

| Tubular adenocarcinoma (well differentiated) | 62 (3.1) |

| Tubular adenocarcinoma (moderately differentiated) | 624 (31.1) |

| Tubular adenocarcinoma (poorly differentiated) | 992 (49.5) |

| Signet ring cell carcinoma | 219 (10.9) |

| Others | 101 (5) |

| Gastrectomy, n (%) | |

| Subtotal | 1127 (56.2) |

| Total | 878 (43.8) |

| Retrieved lymph nodes, n | |

| Range | 12-106 |

| mean ± SD | 28.4 ± 12 |

| Lymph node metastasis, n (%) | |

| Yes | 1079 (53.8) |

| No | 926 (46.2) |

| Lymphovascular invasion, n (%) | |

| Yes | 1023 (51) |

| No | 982 (49) |

| Perineural invasion, n (%) | |

| Yes | 925 (46.1) |

| No | 1080 (53.9) |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy, n (%) | |

| Yes | 1340 (66.8) |

| No | 665 (33.2) |

| Recurrence, n (%) | |

| Yes | 671 (33.5) |

| No | 1334 (66.5) |

| Mortality, n (%) | |

| Yes | 874 (43.6) |

| No | 1131 (56.4) |

| Overall survival (mo) | |

| Range | 0.5-129.7 |

| mean ± SD | 55.3 ± 32.2 |

| Recurrence-free survival (mo) | |

| Range | 0.5-129.7 |

| mean ± SD | 51.1 ± 33.6 |

The mean tumour size was 6.3 ± 3.5 cm (range: 1-48 cm), with 55.3% and 44.7% of the tumours being > 5 cm and ≤ 5 cm, respectively. The tumour locations were the lower-third (59.7%), middle-third (23.1%), and upper-third (17.2%). The depths of invasion were the subserosal layer (43.1%), exposed or invading the serosa (30.4%), the muscularis propria (25.1%), and the submucosal layers (1.4%). The histopathological findings were tubular adenocarcinomas (poorly-differentiated: 49.5%, moderately-differentiated: 31.1%, and well-differentiated: 3.1%), SRC (10.9%), mucinous adenocarcinoma (3.5%), papillary adenocarcinoma (0.3%), neuroendocrine tumours (0.2%), and other histopathological abnormalities (1.3%). The surgical procedures were subtotal (55.2%) and total gastrectomy (44.8%), with a mean number of 28.4 ± 12 retrieved lymph nodes (LNs) (range: 12-106 lymph nodes) and 53.8% of these cases involving LN metastasis. Lymphovascular and perineural invasions was observed in 51% and 46.1% of cases, respectively. Adjuvant chemotherapy was provided to 66.8% of patients, with the recurrence and mortality rates being 33.5% and 43.6%, respectively. The mean OS duration was 55.3 ± 32.2 mo (range: 0.5-129.7 mo) and the mean RFS was 51.1 ± 33.6 mo (range: 0.5-129.7 mo).

Based on the Cox proportional hazards model, OS was independently predicted by advanced age, larger tumour size, lymphovascular invasion, LN metastasis, moderately-to-poorly differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma, and SRC (Table 2). The independent predictors of RFS in this model were advanced age, larger tumour size, lymphovascular invasion, poorly differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma, and SRC (Table 2).

| Characteristic | Overall survival | Recurrence-free survival | ||||

| P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Female | 0.434 | 0.943 | 0.813-1.093 | 0.292 | 0.925 | 0.801-1.069 |

| Age | ||||||

| ≤ 60 yr | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| > 60 yr | 0.001 | 1.723 | 1.502-1.978 | 0.001 | 1.658 | 1.451-1.895 |

| Tumour size | ||||||

| ≤ 5 cm | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| > 5 cm | 0.001 | 1.455 | 1.252-1.690 | 0.001 | 1.505 | 1.302-1.740 |

| Lymphovascular invasion | ||||||

| No | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Yes | 0.001 | 1.678 | 1.450-1.943 | 0.001 | 1.676 | 1.455-1.931 |

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||||

| No | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Yes | 0.047 | 0.866 | 0.752-0.998 | 0.111 | 0.894 | 0.780-1.026 |

| Depth of invasion | ||||||

| Muscularis propria | 0.102 | 0.654 | 0.394-1.088 | 0.160 | 0.696 | 0.419-1.155 |

| Sub-serosal | 0.125 | 0.676 | 0.410-1.115 | 0.200 | 0.721 | 0.437-1.189 |

| Serosal exposed | 0.080 | 0.636 | 0.383-1.055 | 0.142 | 0.685 | 0.413-1.135 |

| Serosal invasion | 0.287 | 0.705 | 0.370-1.342 | 0.272 | 0.697 | 0.366-1.189 |

| Histology | ||||||

| Tubular adenocarcinoma (well) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Tubular adenocarcinoma (moderate) | 0.036 | 1.783 | 1.038-3.061 | 0.069 | 1.562 | 0.967-2.523 |

| Tubular adenocarcinoma (poorly) | 0.008 | 2.070 | 1.211-3.538 | 0.026 | 1.716 | 1.067-2.759 |

| Signet ring cell carcinoma | 0.001 | 2.689 | 1.535-4.707 | 0.001 | 2.290 | 1.387-3.781 |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 0.156 | 1.601 | 0.836-3.066 | 0.236 | 1.431 | 0.791-2.588 |

We also found that the prognostic factors varied according to sex and age (Tables 3 and 4). For example, among men the prognostic factors were age, tumour size, lymphovascular invasion, depth of invasion, moderately-to-poorly differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma, and SRC (Table 3), while among women the prognostic factors were tumour size, and lymphovascular invasion. Among ≤ 60-year-old patients the prognostic factors were tumour size, and lymphovascular invasion (Table 4), while among > 60-year-old patients the prognostic factors were lymphovascular invasion, any tubular adenocarcinoma, SRC, and mucinous adenocarcinoma.

| Characteristic | Male | Female | ||||

| P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | |

| Age | ||||||

| ≤ 60 yr | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| > 60 yr | 0.001 | 1.882 | 1.601-2.213 | 0.136 | 1.204 | 0.943-1.536 |

| Tumour size | ||||||

| ≤ 5 cm | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| > 5 cm | 0.001 | 1.443 | 1.212-1.718 | 0.001 | 1.610 | 1.239-2.090 |

| Lymphovascular invasion | ||||||

| No | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Yes | 0.001 | 1.697 | 1.428-2.017 | 0.001 | 1.587 | 1.238-2.035 |

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||||

| No | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Yes | 0.166 | 0.890 | 0.754-1.050 | 0.437 | 0.907 | 0.709-1.161 |

| Depth of invasion | ||||||

| Muscularis propria | 0.025 | 0.521 | 0.295-0.920 | 0.736 | 1.220 | 0.385-3.866 |

| Sub-serosal | 0.044 | 0.565 | 0.324-0.986 | 0.824 | 1.139 | 0.362-3.587 |

| Serosal exposed | 0.039 | 0.551 | 0.314-0.970 | 0.986 | 0.990 | 0.311-3.147 |

| Serosal invasion | 0.264 | 0.669 | 0.330-1.354 | 0.653 | 0.693 | 0.140-3.434 |

| Histology | ||||||

| Tubular adenocarcinoma (well) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Tubular adenocarcinoma (moderate) | 0.043 | 1.754 | 1.017-3.026 | 0.886 | 0.929 | 0.337-2.559 |

| Tubular adenocarcinoma (poor) | 0.010 | 2.029 | 1.181-3.486 | 0.739 | 0.844 | 0.312-2.282 |

| Signet ring cell carcinoma | 0.001 | 3.153 | 1.769-5.619 | 0.812 | 0.883 | 0.317-2.459 |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 0.359 | 1.390 | 0.688-2.810 | 0.896 | 1.080 | 0.342-3.409 |

| Characteristic | ≤ 60 yr old | > 60 yr old | ||||

| P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Female | 0.300 | 1.116 | 0.907-1.373 | 0.017 | 0.780 | 0.636-0.957 |

| Tumour size | ||||||

| ≤ 5 cm | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| > 5 cm | 0.001 | 1.973 | 1.586-2.454 | 0.086 | 1.187 | 0.976-1.444 |

| Lymphovascular invasion | ||||||

| No | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Yes | 0.001 | 1.783 | 1.441-2.206 | 0.001 | 1.580 | 1.307-1.910 |

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||||

| No | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Yes | 0.485 | 0.929 | 0.756-1.142 | 0.147 | 0.872 | 0.725-1.049 |

| Depth of invasion | ||||||

| Muscularis propria | 0.185 | 0.570 | 0.249-1.308 | 0.371 | 0.746 | 0.392-1.418 |

| Sub-serosal | 0.280 | 0.638 | 0.283-1.441 | 0.472 | 0.792 | 0.420-1.495 |

| Serosal exposed | 0.214 | 0.594 | 0.262-1.350 | 0.465 | 0.786 | 0.412-1.500 |

| Serosal invasion | 0.518 | 0.724 | 0.272-1.929 | 0.549 | 0.765 | 0.318-1.839 |

| Histology | ||||||

| Tubular adenocarcinoma (well) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Tubular adenocarcinoma (moderate) | 0.731 | 0.891 | 0.463-1.718 | 0.010 | 2.547 | 1.246-5.205 |

| Tubular adenocarcinoma (poorly) | 0.929 | 0.972 | 0.514-1.837 | 0.004 | 2.812 | 1.380-5.730 |

| Signet ring cell carcinoma | 0.427 | 1.309 | 0.674-2.543 | 0.001 | 3.652 | 1.700-7.843 |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 0.134 | 0.525 | 0.226-1.220 | 0.002 | 3.847 | 1.648-8.979 |

Based on the logistic regression model, the independent risk factors for LN metastasis were larger tumour size and lymphovascular invasion (Table 5). Among men, the risk of LN metastasis was related to tumour size, lymphovascular invasion, tubular adenocarcinoma classification, and mucinous adenocarcinoma (Table 6), while among women the risk factors for LN metastasis were tumour size, and lymphovascular invasion. Among ≤ 60-year-old patients, the independent risk factors for LN metastasis were larger tumour size, and lymphovascular invasion (Table 7), while among > 60-year-old patients, the independent risk factors were larger tumour size, lymphovascular invasion, and poorly differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma.

| Characteristic | Lymph node metastasis | Univariate | Multivariate | |||

| Yes | No | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 766 (71) | 618 (66.7) | 0.040 | 1.000 | ||

| Female | 313 (29) | 308 (33.3) | 0.840 | 0.682-1.034 | 0.099 | |

| Age | ||||||

| ≤ 60 yr | 573 (53.1) | 496 (53.6) | 0.837 | 1.000 | ||

| > 60 yr | 506 (46.9) | 430 (46.4) | 1.035 | 0.854-1.255 | 0.726 | |

| Tumour size | ||||||

| ≤ 5 cm | 580 (53.8) | 316 (34.1) | 0.001 | 1.000 | ||

| > 5 cm | 499 (46.2) | 610 (65.9) | 0.552 | 0.453-0.674 | 0.001 | |

| Lymphovascular invasion | ||||||

| Yes | 415 (38.5) | 608 (65.7) | 0.001 | 0.356 | 0.294-0.431 | 0.001 |

| No | 664 (61.5) | 318 (34.3) | 1.000 | |||

| Depth of invasion | ||||||

| Muscularis propria | 252 (23.4) | 252 (27.2) | 0.647 | 0.297-1.409 | 0.273 | |

| Sub-serosal | 453 (42) | 412 (44.5) | 0.711 | 0.329-1.537 | 0.386 | |

| Serosal exposed | 327 (30.3) | 233 (25.2) | 0.908 | 0.418-1.975 | 0.808 | |

| Serosal invasion | 30 (2.8) | 18 (1.9) | 1.078 | 0.414-2.809 | 0.877 | |

| Histology | ||||||

| Tubular adenocarcinoma (well) | 46 (4.3) | 16 (1.8) | 0.011 | 1.000 | ||

| Tubular adenocarcinoma (moderate) | 342 (32.3) | 282 (31) | 0.560 | 0.301-1.043 | 0.068 | |

| Tubular adenocarcinoma (poorly) | 519 (49) | 473 (52) | 0.583 | 0.315-1.080 | 0.086 | |

| Signet ring cell carcinoma | 119 (11.2) | 100 (11) | 0.676 | 0.347-1.318 | 0.251 | |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 33 (3.1) | 38 (4.2) | 0.474 | 0.218-1.029 | 0.059 | |

| Characteristic | Male | Female | ||||

| P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | |

| Age | ||||||

| ≤ 60 yr | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| > 60 yr | 0.919 | 1.012 | 0.804-1.274 | 0.512 | 1.127 | 0.789-1.610 |

| Tumour size | ||||||

| ≤ 5 cm | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| > 5 cm | 0.001 | 0.532 | 0.418-0.677 | 0.006 | 0.605 | 0.425-0.863 |

| Lymphovascular invasion | ||||||

| No | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Yes | 0.001 | 0.359 | 0.284-0.453 | 0.001 | 0.357 | 0.254-0.501 |

| Depth of invasion | ||||||

| Muscularis propria | 0.684 | 0.823 | 0.323-2.098 | 0.190 | 0.387 | 0.094-1.601 |

| Sub-serosal | 0.735 | 0.852 | 0.338-2.149 | 0.298 | 0.474 | 0.116-1.035 |

| Serosal exposed | 0.934 | 1.040 | 0.409-2.645 | 0.585 | 0.673 | 0.163-2.779 |

| Serosal invasion | 0.817 | 1.143 | 0.369-3.540 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.160-6.255 |

| Histology | ||||||

| Tubular adenocarcinoma (well) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Tubular adenocarcinoma (moderate) | 0.044 | 0.489 | 0.244-0.980 | 0.853 | 1.157 | 0.247-5.405 |

| Tubular adenocarcinoma (poor) | 0.047 | 0.497 | 0.249-0.992 | 0.726 | 1.312 | 0.288-5.979 |

| Signet ring cell carcinoma | 0.122 | 0.543 | 0.251-1.177 | 0.520 | 1.673 | 0.349-8.015 |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 0.048 | 0.411 | 0.170-0.992 | 0.945 | 1.065 | 0.178-6.387 |

| Characteristic | ≤ 60 yr old | > 60 yr old | ||||

| P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Female | 0.066 | 0.762 | 0.571-1.018 | 0.543 | 0.910 | 0.670-1.235 |

| Tumour size | ||||||

| ≤ 5 cm | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| > 5 cm | 0.001 | 0.452 | 0.344-0.594 | 0.020 | 0.707 | 0.528-0.947 |

| Lymphovascular invasion | ||||||

| No | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Yes | 0.001 | 0.312 | 0.239-0.407 | 0.001 | 0.406 | 0.307-0.536 |

| Depth of invasion | ||||||

| Muscularis propria | 0.024 | 0.169 | 0.036-0.790 | 0.452 | 1.477 | 0.535-4.077 |

| Sub-serosal | 0.046 | 0.211 | 0.046-0.975 | 0.444 | 1.481 | 0.541-4.056 |

| Serosal exposed | 0.122 | 0.298 | 0.064-1.381 | 0.332 | 1.659 | 0.597-4.607 |

| Serosal invasion | 0.324 | 0.422 | 0.076-2.341 | 0.503 | 1.571 | 0.418-5.903 |

| Histology | ||||||

| Tubular adenocarcinoma (well) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Tubular adenocarcinoma (moderate) | 0.340 | 0.644 | 0.261-1.589 | 0.088 | 0.465 | 0.193-1.121 |

| Tubular adenocarcinoma (poor) | 0.788 | 0.885 | 0.364-2.151 | 0.031 | 0.381 | 0.158-0.918 |

| Signet ring cell carcinoma | 0.909 | 0.947 | 0.370-2.424 | 0.166 | 0.496 | 0.184-1.339 |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 0.483 | 0.677 | 0.228-2.014 | 0.068 | 0.346 | 0.111-1.080 |

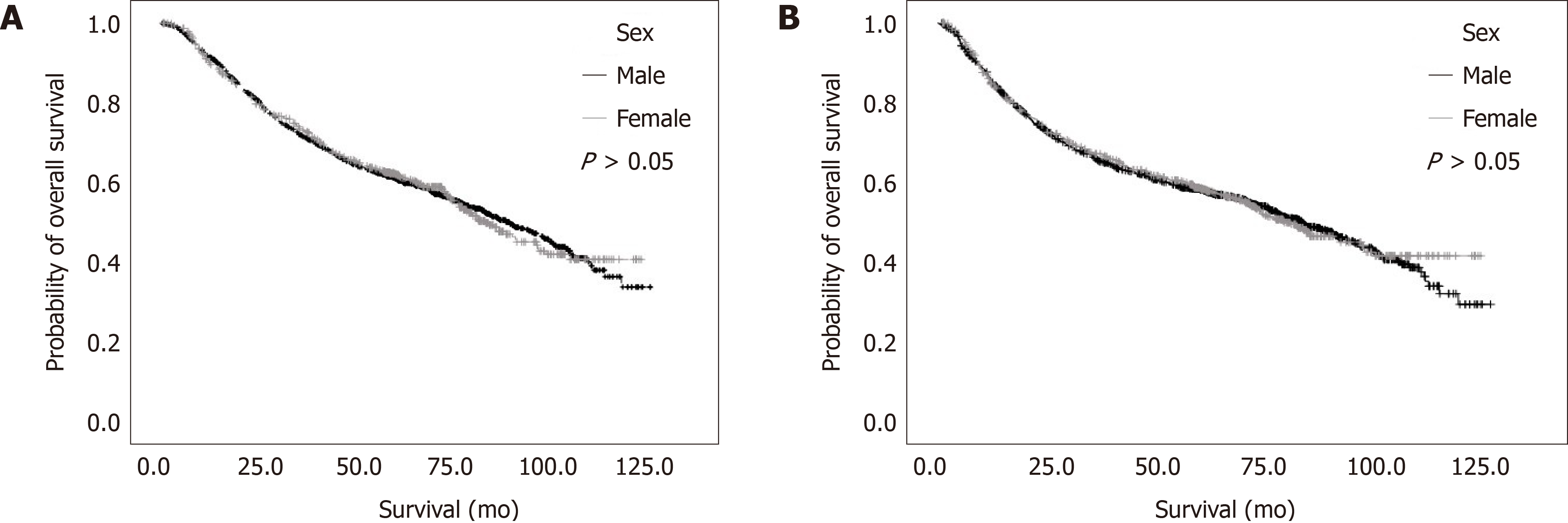

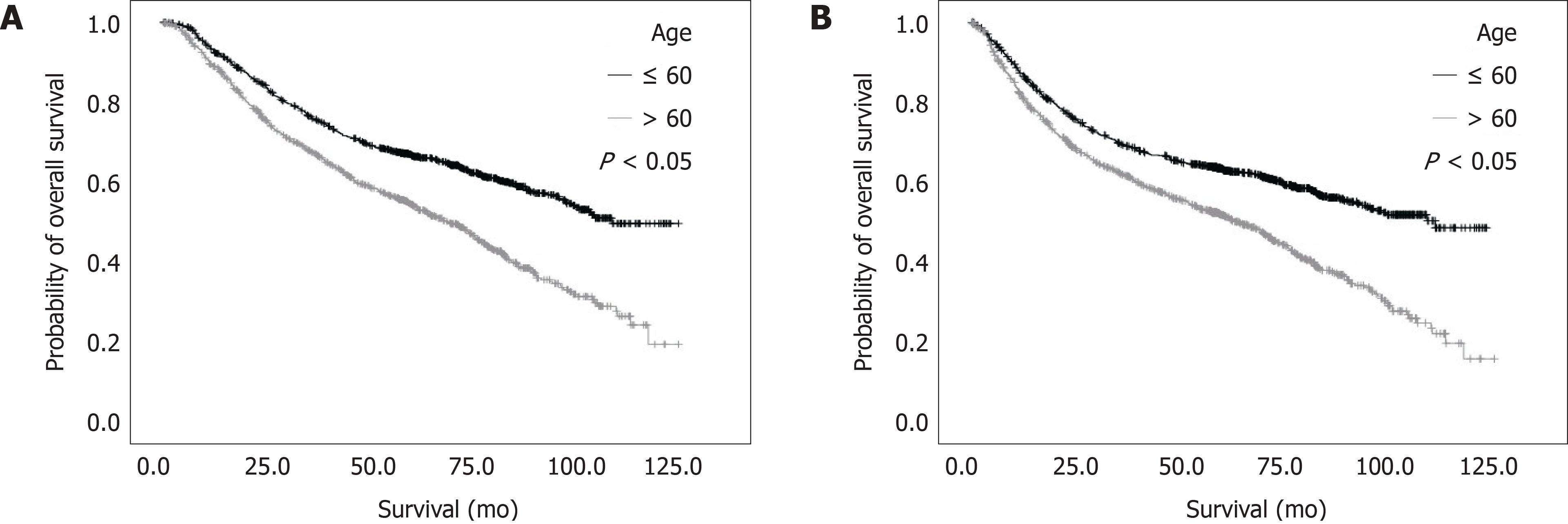

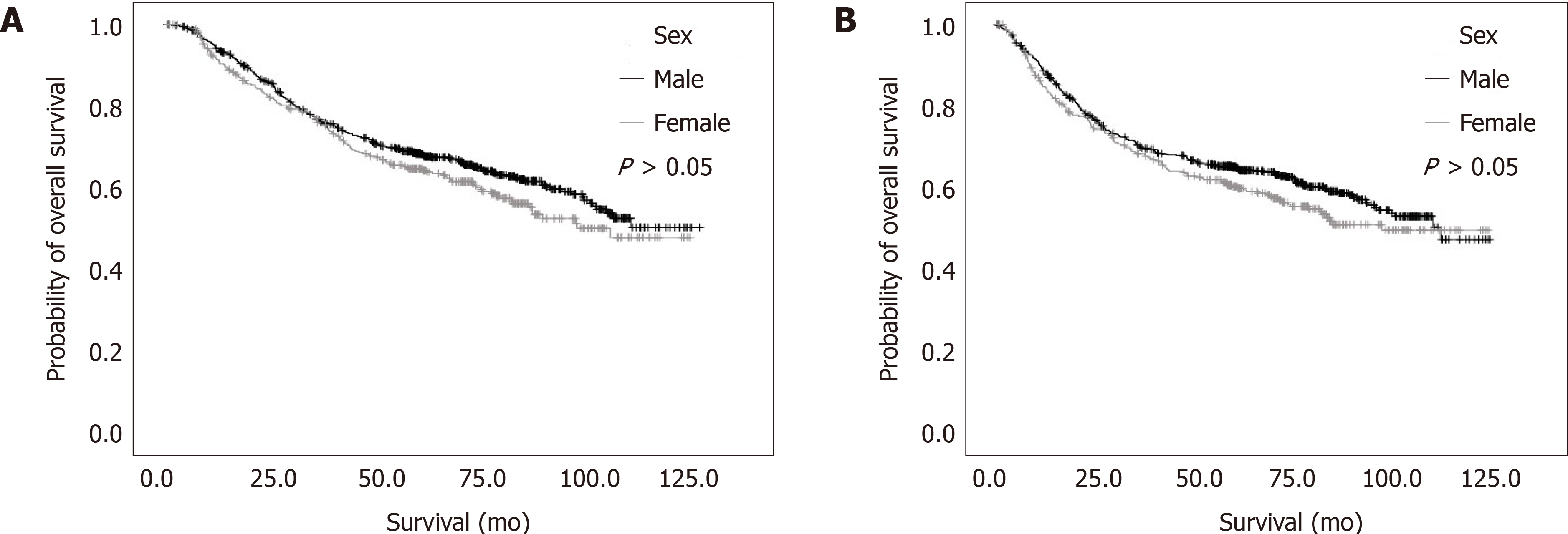

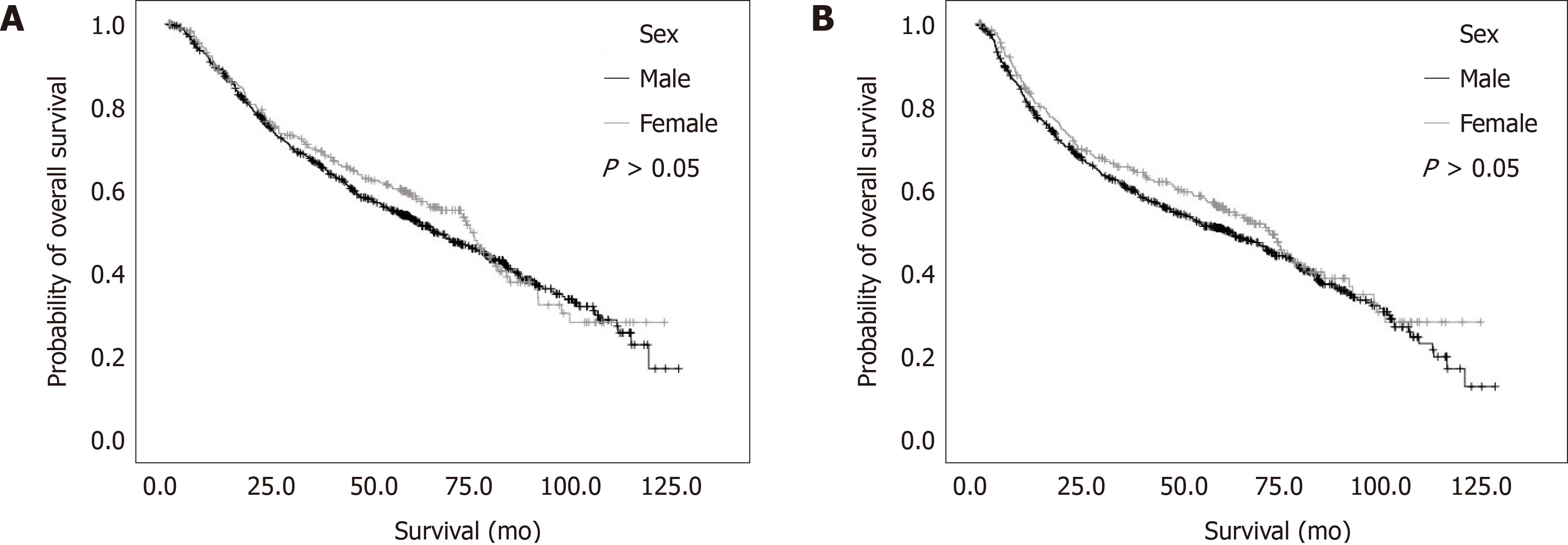

We did not detect significant differences according to sex in the OS (Figure 1A) and RFS (Figure 1B) outcomes of Korean patients with AGC (both P > 0.05). However, the different age groups exhibited significant differences in OS (Figure 2A) and RFS (Figure 2B). We also evaluated whether sex might be associated with different outcomes in each age group, although we did not detect significant differences in OS (Figure 3A) and RFS (Figure 3B) among ≤ 60-year-old or > 60-year-old patients (Figure 4).

Although East Asian countries (including Japan) have survival rates reaching up to 70% for GC[6], the outcomes remain poor in Western countries despite their advances in diagnosis and treatment, as depicted by the 5-year OS rates of < 30%[7]. Thus, a better understanding of the prognostic factors for GC might provide new insights and enhance the treatment of advanced-stage cases. We evaluated the outcomes of 2,005 patients who had been diagnosed with AGC during 2002 and 2007 according to age, which is an independent risk factor for several cancers, including AGC[8]. However, previous studies have used age cut-offs of 50, 30, or 45 years, respectively[8,9]. In our study, we used an age cut-off at 60 years based on recent studies and the new age subdivision suggested by the WHO[9]. Likewise, other studies have compared outcomes among elderly and younger patients with GC; however, they yielded inconclusive results[16,17].

Younger patients may experience poorer survival rates because of their characteristics and different tumour behaviours[18]. For example, Chen et al[19] reported that 56-65-year-old patients exhibited better clinicopathological features and gastric cancer-specific survival rates than other age groups of patients with operable GC. Similarly, Song et al[9] reported that age is related to the prognosis of GC, although younger patients had a higher survival rate after surgery, relative to elderly patients. Our study revealed that OS was independently predicted by advanced age, larger tumour size, lymphovascular invasion, LN metastasis, deeper tumour invasion, moderately-to-poorly differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma, and SRC. These findings may be related to younger patients typically presenting with more advanced disease[18,20]. The better outcomes among older patients may also be related to two factors: (1) The poor tolerance of extensive lymphadenectomy and standardised chemotherapy in older adults[21], which lead clinicians to provide only remedial options to younger patients, as they are generally in better condition and more able to tolerate chemotherapy[22]; and (2) Younger patients have better tolerance of surgery and recovery[23].

Moreover, our study revealed that approximately two-thirds of the patients with AGC were male, which suggests that they may have been more frequently exposed to GC risk factors that are associated with male sex, such as increased alcohol intake and smoking. These factors might contribute to an increased GC incidence later in life[24]. We also found that RFS and OS were independently predicted by advanced age, larger tumour size, lymphovascular invasion, deeper tumour invasion, poorly-differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma, and SRC. These findings conflict with those of Suh et al[25], who reported that age was an independent risk factor for RFS, but not for OS. Several studies have also revealed that a diffuse histological subtype is commonly detected in younger individuals[26,27]. Our study revealed that the histological subtype was significantly associated with GC outcomes among older patients with available histological information.

To the best of our knowledge, there are few studies that have evaluated the survival rates and prognostic factors among patients with AGC. Our study revealed that OS among patients with AGC was independently predicted by older age, larger tumour size, lymphovascular invasion, LN metastasis, deeper tumour invasion, moderately-to-poorly differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma, and SRC. However, LN metastasis and moderately differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma were not risk factors for poor RFS in these patients. Furthermore, there were no significant differences according to sex in the RFS and OS outcomes. Nevertheless, there were significant differences in RFS and OS according to patient age using a cut-off value of 60 years.

However, our study was limited by the small sample size and the lack of a control group. Nevertheless, we provided new data regarding a disease with an increasing incidence in younger patients and adults, which has considerable psychological and social effects. Increased awareness of AGC is needed to ensure that GC is diagnosed at a potentially curable stage.

Gastric cancer has a relatively high prevalence specially in east countries. However the prognosis still poor with those advanced cases. Despite the improvement in diagnostic and treatment.

Although outcomes of advanced gastric cancer is not satisfied. Searching for factors may improve the result and outcomes of treatment may help to improve the prognosis.

This study aimed to see the prognosis factors in advanced gastric cancer according to patient’s age and gender.

2005 patients with advanced gastric cancer who underwent surgical treatment at one Korean single centre between 2002-2007. Retrospectively, data collected and analyzed. Possible prognosis factors were evaluated.

A total of 2005 patients [sex, 1384 men (69%), 621 women (31%)] with advanced gastric cancer. Cox proportional hazards model, overall survival was independently predicted by older age, larger tumour size, lymphovascular invasion, lymph node metastasis, deeper tumour invasion, moderately-to-poorly differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma, and signet ring cell carcinoma. The same model revealed that relapse-free survival was independently predicted by advanced age, larger tumour size, lymphovascular invasion, deeper tumour invasion, poorly differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma, and signet ring cell carcinoma.

Older age was independently predicted factor for poor overall survival and relapse-free survival. However, there were no significant difference found according to gender in relapse-free and overall survival.

Study was limited by the small sample size and the lack of a control group. Nevertheless, we provided new data regarding a disease with an increasing incidence in younger patients and adults, which has considerable psychological and social effects. Increased awareness of advanced gastric cancer is needed to ensure that gastric cancer is diagnosed at a potentially curable stage.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Dumitrascu DL, Lu F, Zhu YM S-Editor: Wang J L-Editor: A E-Editor: Liu MY

| 1. | Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53206] [Cited by in RCA: 55765] [Article Influence: 7966.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (132)] |

| 2. | Jung KW, Won YJ, Kong HJ, Lee ES. Prediction of Cancer Incidence and Mortality in Korea, 2018. Cancer Res Treat. 2018;50:317-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kim C, Lee S, Yang D. What is the prognosis for early gastric cancer with pN stage 2 or 3 at the time of pre-operation and operation. J Korean Gastric Cancer Assoc. 2006;6:114–119. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lu J, Dai Y, Xie JW, Wang JB, Lin JX, Chen QY, Cao LL, Lin M, Tu RH, Zheng CH, Li P, Huang CM. Combination of lymphovascular invasion and the AJCC TNM staging system improves prediction of prognosis in N0 stage gastric cancer: results from a high-volume institution. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Okines A, Verheij M, Allum W, Cunningham D, Cervantes A; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Gastric cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21 Suppl 5:v50-v54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 241] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. GLOBOCAN 2012: Estimated Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide in 2012 v1.0. 16 Dec 2019. Available from: https://publications.iarc.fr/Databases/Iarc-Cancerbases/GLOBOCAN-2012-Estimated-Cancer-Incidence-Mortality-And-Prevalence-Worldwide-In-2012-V1.0-2012. |

| 7. | Karimi P, Islami F, Anandasabapathy S, Freedman ND, Kamangar F. Gastric cancer: descriptive epidemiology, risk factors, screening, and prevention. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:700-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1159] [Cited by in RCA: 1324] [Article Influence: 120.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Li Q, Cai G, Li D, Wang Y, Zhuo C, Cai S. Better long-term survival in young patients with non-metastatic colorectal cancer after surgery, an analysis of 69,835 patients in SEER database. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Song P, Wu L, Jiang B, Liu Z, Cao K, Guan W. Age-specific effects on the prognosis after surgery for gastric cancer: A SEER population-based analysis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:48614-48624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Anderson WF, Camargo MC, Fraumeni JF, Correa P, Rosenberg PS, Rabkin CS. Age-specific trends in incidence of noncardia gastric cancer in US adults. JAMA. 2010;303:1723-1728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 354] [Cited by in RCA: 356] [Article Influence: 23.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kim BS, Oh ST, Yook JH, Kim BS. Signet ring cell type and other histologic types: differing clinical course and prognosis in T1 gastric cancer. Surgery. 2014;155:1030-1035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Adachi Y, Yasuda K, Inomata M, Sato K, Shiraishi N, Kitano S. Pathology and prognosis of gastric carcinoma: well versus poorly differentiated type. Cancer. 2000;89:1418-1424. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Korean Gastric Cancer Association. Clinical management guideline, 2018. 16 Dec 2019. Available from: https://synapse.koreamed.org/DOIx.php?id=10.5230/jgc.2019.19.e8. |

| 14. | Hamilton SR, Aaltonen LA. Pathology and genetics of tumors of the digestive system. Lyon: IARC Press; 2000. |

| 15. | Lee HH, Song KY, Park CH, Jeon HM. Undifferentiated-type gastric adenocarcinoma: prognostic impact of three histological types. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Park JC, Lee YC, Kim JH, Kim YJ, Lee SK, Hyung WJ, Noh SH, Kim CB. Clinicopathological aspects and prognostic value with respect to age: an analysis of 3362 consecutive gastric cancer patients. J Surg Oncol. 2009;99:395-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Nakamura R, Saikawa Y, Takahashi T, Takeuchi H, Asanuma H, Yamada Y, Kitagawa Y. Retrospective analysis of prognostic outcome of gastric cancer in young patients. Int J Clin Oncol. 2011;16:328-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Smith BR, Stabile BE. Extreme aggressiveness and lethality of gastric adenocarcinoma in the very young. Arch Surg. 2009;144:506-510. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chen J, Chen J, Xu Y, Long Z, Zhou Y, Zhu H, Wang Y, Shi Y. Impact of Age on the Prognosis of Operable Gastric Cancer Patients: An Analysis Based on SEER Database. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e3944. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wang Z, Xu J, Shi Z, Shen X, Luo T, Bi J, Nie M. Clinicopathologic characteristics and prognostic of gastric cancer in young patients. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:1043-1049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lima IB, Pernambuco L. Morbidade hospitalar por acidente vascular encefálico e cobertura fonoaudiológica no Estado da Paraíba, Brasil. Audiology-Communication Research. 2017;22:e1822. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Liu S, Feng F, Xu G, Liu Z, Tian Y, Guo M, Lian X, Cai L, Fan D, Zhang H. Clinicopathological features and prognosis of gastric cancer in young patients. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kwon KJ, Shim KN, Song EM, Choi JY, Kim SE, Jung HK, Jung SA. Clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of signet ring cell carcinoma of the stomach. Gastric Cancer. 2014;17:43-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wang Z, Butler LM, Wu AH, Koh WP, Jin A, Wang R, Yuan JM. Reproductive factors, hormone use and gastric cancer risk: The Singapore Chinese Health Study. Int J Cancer. 2016;138:2837-2845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Suh DD, Oh ST, Yook JH, Kim BS, Kim BS. Differences in the prognosis of early gastric cancer according to sex and age. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2017;10:219-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Takatsu Y, Hiki N, Nunobe S, Ohashi M, Honda M, Yamaguchi T, Nakajima T, Sano T. Clinicopathological features of gastric cancer in young patients. Gastric Cancer. 2016;19:472-478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 27. | Amorim CA, Moreira JP, Rial L, Carneiro AJ, Fogaça HS, Elia C, Luiz RR, de Souza HS. Ecological study of gastric cancer in Brazil: geographic and time trend analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:5036-5044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |