Published online Apr 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i8.1414

Peer-review started: December 15, 2019

First decision: January 7, 2020

Revised: March 3, 2020

Accepted: April 15, 2020

Article in press: April 15, 2020

Published online: April 26, 2020

Processing time: 128 Days and 18.2 Hours

Retained common bile duct (CBD) stone after an acute episode of biliary pancreatitis is of paramount importance since stone extraction is mandatory.

To generate a simple non-invasive score to predict the presence of CBD stone in patients with biliary pancreatitis.

We performed a retrospective study including patients with a diagnosis of biliary pancreatitis. One hundred and fifty-four patients were included. Thirty-three patients (21.5%) were diagnosed with CBD stone by endoscopic ultrasound (US).

In univariate analysis, age (OR: 1.048, P = 0.0004), aspartate transaminase (OR: 1.002, P = 0.0015), alkaline phosphatase (OR: 1.005, P = 0.0005), gamma-glutamyl transferase (OR: 1.003, P = 0.0002) and CBD width by US (OR: 1.187, P = 0.0445) were associated with CBD stone. In multivariate analysis, three parameters were identified to predict CBD stone; age (OR: 1.062, P = 0.0005), gamma-glutamyl transferase level (OR: 1.003, P = 0.0003) and dilated CBD (OR: 3.685, P = 0.027), with area under the curve of 0.8433. We developed a diagnostic score that included the three significant parameters on multivariate analysis, with assignment of weights for each variable according to the co-efficient estimate. A score that ranges from 51.28 to 73.7 has a very high specificity (90%-100%) for CBD stones, while a low score that ranges from 9.16 to 41.04 has a high sensitivity (82%-100%). By performing internal validation, the negative predictive value of the low score group was 93%.

We recommend incorporating this score as an aid for stratifying patients with acute biliary pancreatitis into low or high probability for the presence of CBD stone.

Core tip: Approximately 20%-30% of patients with acute biliary pancreatitis will retain their common bile duct (CBD) stone. Early identification of these patients is critical since stone extraction is mandatory. We performed a single center retrospective study including 154 patients who were followed for simple clinical, laboratory and radiological parameters. We generated a simple diagnostic score including 3 variables (age, gamma-glutamyl transferase level and CBD width by ultrasound) with excellent diagnostic performance and capability of stratifying patients into low or high risk for retained CBD stone.

- Citation: Khoury T, Kadah A, Mahamid M, Mari A, Sbeit W. Bedside score predicting retained common bile duct stone in acute biliary pancreatitis. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(8): 1414-1423

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i8/1414.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i8.1414

Gallstones are considered the most common cause of acute pancreatitis[1]. According to previous studies they represent about 40%-50% of all causes of acute pancreatitis[2-4]. Gallbladder stones are considered a major health problem in developed countries, with an overall prevalence among adult populations between 10%-20%[5,6].

Acute biliary pancreatitis (ABP) results from migration of gallbladder stone through the cystic duct into the common bile duct (CBD) which causes either transient or persistent obstruction of the pancreatic duct, resulting in subsequent development of pancreatitis. Most gallstones are smaller than 5 mm in diameter[7-9]. Only a small percentage, around 25% of patients presenting with ABP will have retained CBD stones, while the majority of CBD stones will pass spontaneously given their small size[10-12]. Therefore, CBD imaging is necessary to identify those patients with ABP who have persistent CBD stones[13]. Modalities available for investigation include endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), laparoscopic ultrasound, and intraoperative cholangiography[14]. In clinical practice, the decision to clarify suspicion of CBD stone by imaging or to proceed directly to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) due to strong suspicion, is based on a combination of clinical, laboratory and ultrasound or computed tomography findings, in addition to diagnostic methods and resources available in each medical center. However, before proceeding to ERCP with its complication rate of about 5%–10% including post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP), cholangitis, perforation, and hemorrhage[15-17], presence of CBD stone should be ascertained. The American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) has proposed a strategy to assign the risk of CBD stones in patients with symptomatic cholelithiasis based on clinical, laboratory and sonographic parameters. They were divided according to strength of the parameters into “very strong”, “strong” and “moderate” predictors. The proposed strategy advocate proceeding to ERCP in patients with one “very strong” or two “strong” predictors, or performing an investigative procedure in patients with parameters ranked otherwise[14]. A recent study reported that the specificity of the ASGE very strong predictors was 74% and the positive predictive value (PPV) was 64% with more than one-third of patients undergoing diagnostic ERCP[18]. Although no single parameter consistently and strongly predicts the existence of CBD stones, previous studies have shown that combining clinical, laboratory and imaging predictors together improve the diagnostic accuracy of CBD stones[19-21]. In these guidelines, clinical gallstone pancreatitis by itself received moderate strength in predicting CBD stones[14]. However, we believe that this group is not homogeneous and includes a diverse population with different probabilities of suffering from retained CBD stone. Therefore, this probability may be influenced by additional parameters that deserve clarifying in order to offer the appropriate treatment for each patient.

The aim of the present study was to develop a simple, practical, non-invasive score combining routinely-determined and easily available clinical, laboratory and radiological parameters to predict the presence of CBD stones in patient’s presenting with acute biliary pancreatitis

The study cohort consisted of all patients over 18 years old with acute pancreatitis based on clinical, laboratory and radiological criteria, and hospitalized in Galilee Medical Center, Israel, between 2012-2018. The diagnostic criteria for acute pancreatitis included typical abdominal pain, elevation of pancreatic enzymes at least three times the upper normal limit and the presence of typical findings of pancreatic inflammation at imaging.

All underwent EUS examination for investigation of suspected underlying biliary stones [abnormal bilirubin, elevated liver enzymes or dilated CBD on ultrasound (US)], and showed evidence of gallbladder stones by US. In our medical center, EUS is the procedure of choice for suspected CBD stones. A recent meta-analysis found EUS to have high sensitivity of 84%-100% and specificity of 94%-100% in detecting CBD stones[22] and EUS has recently been proposed as the new gold standard in the diagnosis of CBD stones[23]. Exclusion criteria included patients with established alternative cause for acute pancreatitis (such as hyperlipidemia, hypercalcemia, alcohol, congenital pancreatic anomalies and genetic predisposition).

All medical records of eligible patients were reviewed and the following parameters were collected: Demographic data (age, gender), laboratory tests [alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate transaminase, alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), total bilirubin, white blood cells], and radiologic findings (gallbladder and CBD stones by US and EUS, CBD width as assessed by imaging). The laboratory parameters and the ultrasonographic measurement were assessed up to 24 h prior to the EUS performance.

CBD width up to 6 mm was considered normal; while greater values were considered dilatation of the duct even in patients after cholecystectomy since a search of the professional literature did not yield firm values of the diameter in patients after cholecystectomy. All EUS examinations throughout the study were performed by an experienced endoscopist with a high volume of examinations over 15 years’ experience in the field of advanced endoscopy. The study protocol was approved by our medical center’s IRB. Written informed consent was waived by the IRB due to the retrospective, non-interventional nature of the study.

Before any statistical processing and analysis, data were visually inspected and checked for outliers. Descriptive statistics performed for the purpose of comparison between the two groups of patients, with and without common bile duct stones. Continuous variables were computed as arithmetic mean and standard deviation, whereas categorical variables were expressed as percentages. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were generated to calculate the odds ratios (OR) of several parameters with a backward selection type used. For the purpose of generation of a new multivariate regression model that encompassed parameters including (age, CBD width by US and GGT enzyme level), we credited a weight to each factor based on its coefficient estimates. Receiver operator characteristics (ROC) curve, odds ratio and positive likelihood ratio were used for diagnostic accuracy estimation. Results with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed by using the statistical analysis software [SAS Vs 9.4 Copyright (c) 2016 by SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States].

Overall, 1750 patients underwent EUS during the study period. Among them, a total of 154 patients fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for acute pancreatitis who underwent EUS for assessment of CBD stone were included in the study. Among them, 121 patients (78.5%) did not have CBD stones according to EUS (group A) compared to 33 patients (21.5%) who did (group B). The mean age in groups A and B were 54.8 ± 18.8 and 68.9 ± 14.3 years, respectively. Fifty-seven patients in group A and 11 in group B were males. The mean CBD width by US was higher in group B compared to group A (7.3 mm vs 6.4 mm). Table 1 demonstrates demographic and laboratory parameters.

| Parameters | Group A (without stones) | Group B (with stones) |

| Number of patients | 121 | 33 |

| Age (yr) (mean ± SD) | 54.8 ± 18.8 | 68.9 ± 14.3 |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Male | 57 (47) | 11 (33.3) |

| Female | 64 (53) | 22 (66.7) |

| Alanine aminotransferase, U/L | 171.9 ± 238.9 | 363.3 ± 347 |

| Aspartate transaminase, U/L | 170.7 ± 267.4 | 387.7 ± 290.5 |

| Alkaline phosphatase, U/L | 143.6 ± 122.1 | 246.7 ± 133.1 |

| Gamma-glutamyltransferase, U/L | 291.1 ± 284 | 594.4 ± 385.2 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 2.2 ± 5.2 | 3.4 ± 2.6 |

| White blood cells (× 103/cm) | 11.6 ± 4.5 | 12.7 ± 4.7 |

| Common bile duct width by US (mm) | 6.4 ± 1.6 | 7.3 ± 2.9 |

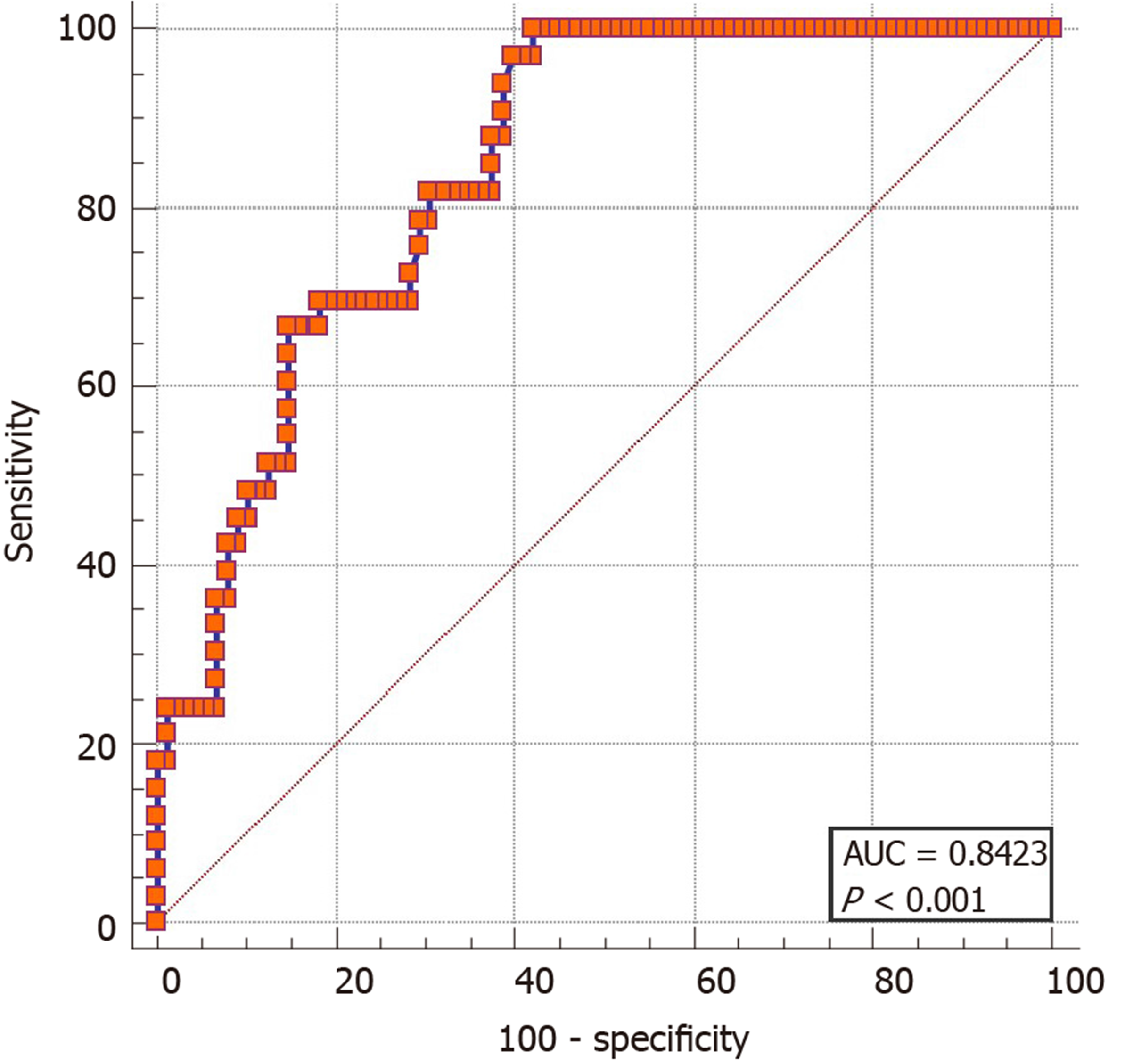

In univariate regression analysis, several predictors of CBD stones in acute biliary pancreatitis were statistically significant (Table 2), including: Age (OR: 1.048, 95%CI: 1.021-1.076, P = 0.0004), aspartate transaminase (OR: 1.002, 95%CI: 1.001-1.004, P = 0.0015), alkaline phosphatase (OR: 1.005, 95%CI: 1.002-1.008, P = 0.0005), GGT (OR: 1.003, 95%CI: 1.001-1.004, P = 0.0002) and CBD width by US (OR: 1.187, 95%CI: 1.004-1.402, P = 0.0445). On the other hand, total bilirubin shows non-statistically significant difference between the two groups (OR: 1.033, 95%CI: 0.964-1.108, P = 0.35) (Table 2). In multivariate regression analysis, three parameters were identified to significantly predict CBD stones: Age (OR: 1.062, 95%CI: 1.026-1.097, P = 0.0005), GGT level (OR: 1.003, 95%CI: 1.001-1.004, P = 0.0003) and dilated CBD (OR: 3.685, 95%CI: 1.160-11.711, P = 0.027), with area under the curve of 0.8433 determined by a ROC curve (Figure 1).

| Parameter | Odds ratio | Lower 95% confidence limit for odds ratio | Upper 95% confidence limit for odds ratio | P value |

| Age | 1.048 | 1.021 | 1.076 | 0.0004 |

| Gender, male vs female | 0.573 | 0.258 | 1.276 | 0.1728 |

| Aspartate transaminase | 1.002 | 1.001 | 1.004 | 0.0015 |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 1.005 | 1.002 | 1.008 | 0.0005 |

| Gamma-glutamyltransferase | 1.003 | 1.001 | 1.004 | 0.0002 |

| Total bilirubin | 1.033 | 0.964 | 1.108 | 0.3515 |

| White blood cells | 1.052 | 0.970 | 1.142 | 0.2190 |

| Common bile duct width by US (mm) | 1.187 | 1.004 | 1.402 | 0.0445 |

| Common bile duct dilation by US | 4.032 | 1.601 | 10.153 | 0.0031 |

For the purpose of structuring a diagnostic score, rounded co-efficient estimates were calculated and accordingly each significant parameter on multivariate regression analysis was assigned a weight according to the estimates (Table 3). Then we developed a diagnostic equation [0.5 × age (years) + 0.02 × GGT (U/L) + 10 × CBD width (mm) by US] that generates cut-off points of the parameters included into the equation (age in years, and GGT (U/L) and CBD width in millimeters by US) with their corresponding sensitivity, specificity, PPV and negative predictive value (NPV), with ROC curve for this diagnostic score of 0.8423 (OR: 1.136, 95%CI: 1.079-1.196, P < 0.0001, likelihood ratio 39.6) (Figure 2). Table 4 demonstrates the equation cut-off points with their corresponding statistic diagnostic values. As shown, score that ranged from 51 to 74 had a very high specificity (90%-100%) for CBD stones, suggesting that these patients might be referred directly to ERCP. By performing internal validation, we found that in this group of 23 patients, 15 were found to have CBD stone (65.2%). On the other hand, a score that ranges from 9 to 41 has a high sensitivity (82%-100%), suggesting that these patients might be managed without further endoscopic intervention. This group consisted of 97 patients, and only seven were found to have CBD stone (7.2%) with NPV of 93%. The third group, with a score of 41-51, needed further investigation by EUS or MRCP to rule out CBD stone. In this group of 34 patients, 11 patients were diagnosed with CBD stone (32.3%).

| Parameters | Coefficient estimate | Odds ratio (95%CI) | P value | Weights appointed for the score |

| Age | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 1.061 (1.026-1.097) | 0.0005 | × 0.5 |

| Dilated common bile duct by US | 1.3 ± 0.058 | 3.685 (1.160-11.711) | 0.0270 | × 10 |

| Gamma-glutamyltransferase (U/L) | 0.002 ± 0.0007 | 1.003 (1.001-1.004) | 0.0003 | × 0.02 |

| Score | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV |

| 51-74 | 20-46 | 90-100 | 65-100 | 77-83 |

| 41-51 | 52-79 | 70-88 | 50-61 | 83-90 |

| 9-41 | 82-100 | 58-69 | 47-50 | 91-100 |

Although the majority of CBD stones causing acute pancreatitis, pass spontaneously through the papilla, still about 20%-30% of these stones are retained in the bile ducts with the potential of causing recurrent acute pancreatitis or cholangitis that may lead to adverse outcome[10-12]. This subset of patients comprises the most problematic group among those hospitalized with ABP and all diagnostic efforts should be carried out in order to identify them and offer treatment to release the obstructing bile duct stone. Early ERCP in patients with persistent CBD stone decreases the rate of biliary complications such as cholangitis, and improves clinical outcomes[24,25]. Previous studies have attempted to assess various clinical, laboratory and radiological parameters including liver function tests and ultrasound findings to predict CBD stone[26,27]. However, individual components of liver function test and US findings (CBD width) have limited diagnostic yield[28]. The ASGE-proposed strategy assigns risk of CBD stone in patients with symptomatic cholelithiasis according to strength of parameters where clinical gallstone pancreatitis is considered a moderate predictor. However, those parameters have limited diagnostic accuracy[14]. Several imaging tools are available for the diagnosis of CBD stones, including MRCP, EUS and ERCP; however, these tools are either invasive or associated with certain morbidity and mortality (ERCP and EUS) or they are expensive, such as MRCP[29]. These modalities are usually used to confirm or treat suspected CBD stone based on clinical, laboratory and US or computed tomography findings. Although the ASGE-proposed strategy to assign risk of CBD stone considers clinical gallstone pancreatitis a moderate predictor of CBD stone, this is a non-homogeneous group of patients with diverse clinical presentations under the same diagnosis of acute pancreatitis, and thus have different probabilities of suffering from retained CBD stone. These probabilities may be influenced by additional parameters that deserve clarifying in order to offer the appropriate treatment for each patient.

In an attempt to isolate and identify this small, albeit high-risk group of patients with retained CBD stone, we retrospectively identified and integrated clinical, laboratory and radiological parameters that were most predictive of the presence of CBD stones in patients with acute pancreatitis into a simple bedside diagnostic score. Those patients would most benefit from direct referral to therapeutic ERCP, saving them the potential complications of invasive and costly diagnostic procedures such as EUS and MRCP. We could identify that advanced age, abnormal GGT level and dilated CBD by US were the most powerful factors predicting the presence of bile duct stone in biliary pancreatitis patients. Our results are in line with previous studies; it is well known that the prevalence of gallstone diseases including CBD stones increases with age[19]. A former study showed that among patients referred for EUS for evaluation of CBD stone, the prevalence has increased up to 32% in patients above 70 years of age as compared to 14% in patients less than 70 years of age[20]. Another study demonstrated that CBD width above 6 mm showed significant positive correlation with CBD stones[30]. However, the sole dilatation of CBD on abdominal imaging tends to support the diagnosis of gallstone pancreatitis with variable and limited sensitivity of 55%-91%. Moreover, GGT level was shown to be the most significant predictor for CBD stones as being demonstrated by previous two studies[31,32], with the highest NPV among other non-invasive parameters[31], but had limited PPV and sensitivity. Therefore, several investigators addressed the performance of multiple variables in predicting high probability of CBD stone[19-21].

By integrating patient age in years, GGT value in U/L and dilated CBD as defined by > 6 mm in width by US, we could generate a simple diagnostic score. This method can provide practitioners with a simple bedside tool to stratify patients into three different groups according to the above-mentioned equation and offer them the appropriate treatment while saving unnecessary investigations. According to this equation score that ranges from 51 to 74 has a very high specificity (90%-100%) for CBD stones, this subset of patients might be referred directly to ERCP. A score that ranges from 9 to 41 has a high sensitivity (82%-100%), suggesting that this group might not benefit from invasive costly investigative procedures and may be managed conservatively without further endoscopic intervention. The third group with a score of 41 to 51 merits additional investigation such as EUS or MRCP because of intermediate probability of CBD stone. These results clearly show that the probability of having a retained CBD stone in patients with acute biliary pancreatitis is influenced by additional parameters. Thus, they should not be regarded as a homogenous group, as this strategy may lead to unnecessary investigations where the probability of choledocholithiasis is high enough to warrant therapeutic ERCP or low enough to refrain from further investigation.

The limitations of our study are its retrospective nature of data collection and the fact that it was conducted in a single center. another limitation is that we didn’t validate our findings in an independent validation cohort. Thus, our findings should be validated by an external validation cohort.

In conclusion, we have developed a scoring system based on three parameters to predict the presence of CBD stone in patients admitted with ABP. Our study has clinical implications, as it might be used as an important aid for practitioners to guide them towards a more prudent decision regarding therapeutic plans for their patients. In this way, they may offer therapeutic ERCP when the probability of CBD stone is high, and avoid unnecessary investigations in patients with low probability of CBD stone.

Gallbladder stones are the commonest cause of acute biliary pancreatitis. Despite that most of the stones are expelled spontaneously through the papilla due to their small size; about 20% to 30% of patients with acute biliary pancreatitis will have persistent common bile duct (CBD) stones. Thus, it is important to identify this subset pf patients since they will need endoscopic stone removal. In real clinical practice, the decision to perform an imaging modality for clarifying a suspicion of CBD stone or to proceed directly to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) because of strong suspicion of CBD stone is mostly based on combinations of clinical, laboratory and ultrasound findings. Many investigators have noted that the probability of CBD stones is higher in the presence of multiple predictors. We characterized clinical, laboratory and radiological parameters which are easily available that can predict the presence of retained CBD stones among patients hospitalized with acute biliary pancreatitis.

The main driver for performing this study was to develop simple bedside score based on easily available parameters that predicts the presence of retained biliary stones, since identification of CBD stone is crucial to relieve biliary obstruction. This score might stratify patients into low or high-risk probability for retained CBD stone and subsequently assist clinicians in performing further confirmatory/therapeutic tests.

Given that retained biliary in the setting of acute biliary pancreatitis required performing certain imaging such as endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) which are either invasive or not widely available, we aimed to explore simple easily available clinical, laboratory and imaging parameters that predict CBD stone with good statistical performance.

We performed a single center retrospective case control study including 154 patients with presumed diagnosis of acute biliary pancreatitis who underwent EUS. The strength of our study is that we relied on EUS as a gold standard for the diagnosis of CBD stones, and second that we aimed to combine several parameters to generate scoring system that could predict CBD stone with high probability.

After assessment of several clinical, laboratory and radiological parameters, we were able to identify 3 parameters that were statistically significant on univariate and multivariate regression analysis including age, GGT level and CBD width by US. Using these variables, we generated a score predicting the presence of retained CBD stones. A score that ranges from 51.28 to 73.7 has a very high specificity (90%-100%) for CBD stones, while a low score that ranges from 9.16 to 41.04 has a high sensitivity (82%-100%), as the patients with the higher score might be referred immediately for ERCP without the need for further investigations, while the low score cut-off points might benefit from watch and see strategy or other confirmatory tests for CBD stones.

For the first time, we were able to generate a simple scoring system that predicts the presence of retained CBD stones among patients with acute biliary pancreatitis. Currently, the professional societies including the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and the ESGE are relying on individualized predictors of CBD stones. The ability to incorporate several variables into one scoring system further improve the diagnostic accuracy of this score, as is known that combining several predictors for CBD stone is superior to each predictor alone. Thus, our score might be already introduced into the daily clinical practice that guide therapeutic decisions.

The diagnosis of retained CBD stone in acute biliary pancreatitis is somehow challenging as it based on single abnormal laboratory or ultrasonographic tests. However, once a suspicion is raised, most clinicians proceed to other confirmatory tests, mainly EUS which is invasive test or MRCP which is costly and not easily available. However, as we shown that combining predictors for CBD stone into one scoring system had an excellent diagnostic performance. This will allow clinicians to avoid performing other unnecessary imaging studies. Large prospective cohort studies assessing combination of several CBD stone simple predictors are warranted.

Manuscript source: Invited Manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Israel

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Fujita K, Marickar F, Wan QQ, Wong YC S-Editor: Wang J L-Editor: A E-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Tenner S, Baillie J, DeWitt J, Vege SS; American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology guideline: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1400-1416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1232] [Cited by in RCA: 1383] [Article Influence: 115.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 2. | Krishna SG, Hinton A, Oza V, Hart PA, Swei E, El-Dika S, Stanich PP, Hussan H, Zhang C, Conwell DL. Morbid Obesity Is Associated With Adverse Clinical Outcomes in Acute Pancreatitis: A Propensity-Matched Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1608-1619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Frey CF, Zhou H, Harvey DJ, White RH. The incidence and case-fatality rates of acute biliary, alcoholic, and idiopathic pancreatitis in California, 1994-2001. Pancreas. 2006;33:336-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yadav D, Lowenfels AB. Trends in the epidemiology of the first attack of acute pancreatitis: a systematic review. Pancreas. 2006;33:323-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 452] [Cited by in RCA: 472] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kratzer W, Mason RA, Kächele V. Prevalence of gallstones in sonographic surveys worldwide. J Clin Ultrasound. 1999;27:1-7. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Shaffer EA. Gallstone disease: Epidemiology of gallbladder stone disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20:981-996. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 444] [Cited by in RCA: 488] [Article Influence: 25.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 7. | Anderloni A, Repici A. Role and timing of endoscopy in acute biliary pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:11205-11208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cavdar F, Yildar M, Tellioğlu G, Kara M, Tilki M, Titiz Mİ. Controversial issues in biliary pancreatitis: when should we perform MRCP and ERCP? Pancreatology. 2014;14:411-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gurusamy KS, Giljaca V, Takwoingi Y, Higgie D, Poropat G, Štimac D, Davidson BR. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography versus intraoperative cholangiography for diagnosis of common bile duct stones. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;CD010339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lefemine V, Morgan RJ. Spontaneous passage of common bile duct stones in jaundiced patients. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2011;10:209-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lee SL, Kim HK, Choi HH, Jeon BS, Kim TH, Choi JM, Ku YM, Kim SW, Kim SS, Chae HS. Diagnostic value of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography to detect bile duct stones in acute biliary pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2018;18:22-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tranter SE, Thompson MH. Spontaneous passage of bile duct stones: frequency of occurrence and relation to clinical presentation. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2003;85:174-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Navarro-Sanchez A, Ashrafian H, Laliotis A, Qurashi K, Martinez-Isla A. Single-stage laparoscopic management of acute gallstone pancreatitis: outcomes at different timings. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2016;15:297-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee. Maple JT, Ben-Menachem T, Anderson MA, Appalaneni V, Banerjee S, Cash BD, Fisher L, Harrison ME, Fanelli RD, Fukami N, Ikenberry SO, Jain R, Khan K, Krinsky ML, Strohmeyer L, Dominitz JA. The role of endoscopy in the evaluation of suspected choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 380] [Cited by in RCA: 335] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 15. | Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, Moore JP, Fennerty MB, Ryan ME, Shaw MJ, Lande JD, Pheley AM. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1716] [Cited by in RCA: 1689] [Article Influence: 58.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 16. | Masci E, Toti G, Mariani A, Curioni S, Lomazzi A, Dinelli M, Minoli G, Crosta C, Comin U, Fertitta A, Prada A, Passoni GR, Testoni PA. Complications of diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: a prospective multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:417-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 625] [Cited by in RCA: 613] [Article Influence: 25.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Christensen M, Matzen P, Schulze S, Rosenberg J. Complications of ERCP: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:721-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 305] [Cited by in RCA: 299] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | He H, Tan C, Wu J, Dai N, Hu W, Zhang Y, Laine L, Scheiman J, Kim JJ. Accuracy of ASGE high-risk criteria in evaluation of patients with suspected common bile duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;86:525-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Barkun AN, Barkun JS, Fried GM, Ghitulescu G, Steinmetz O, Pham C, Meakins JL, Goresky CA. Useful predictors of bile duct stones in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. McGill Gallstone Treatment Group. Ann Surg. 1994;220:32-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Prat F, Meduri B, Ducot B, Chiche R, Salimbeni-Bartolini R, Pelletier G. Prediction of common bile duct stones by noninvasive tests. Ann Surg. 1999;229:362-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bose SM, Mazumdar A, Prakash VS, Kocher R, Katariya S, Pathak CM. Evaluation of the predictors of choledocholithiasis: comparative analysis of clinical, biochemical, radiological, radionuclear, and intraoperative parameters. Surg Today. 2001;31:117-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Shah AP, Mourad MM, Bramhall SR. Acute pancreatitis: current perspectives on diagnosis and management. J Inflamm Res. 2018;11:77-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Gabbrielli A, Pezzilli R, Uomo G, Zerbi A, Frulloni L, Rai PD, Castoldi L, Costamagna G, Bassi C, Carlo VD. ERCP in acute pancreatitis: What takes place in routine clinical practice? World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;2:308-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Forsmark CE, Baillie J; AGA Institute Clinical Practice and Economics Committee; AGA Institute Governing Board. AGA Institute technical review on acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2022-2044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 494] [Cited by in RCA: 505] [Article Influence: 28.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Forsmark CE, Vege SS, Wilcox CM. Acute Pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1972-1981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 615] [Cited by in RCA: 558] [Article Influence: 62.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sherman JL, Shi EW, Ranasinghe NE, Sivasankaran MT, Prigoff JG, Divino CM. Validation and improvement of a proposed scoring system to detect retained common bile duct stones in gallstone pancreatitis. Surgery. 2015;157:1073-1079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Cohen ME, Slezak L, Wells CK, Andersen DK, Topazian M. Prediction of bile duct stones and complications in gallstone pancreatitis using early laboratory trends. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:3305-3311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Freitas ML, Bell RL, Duffy AJ. Choledocholithiasis: evolving standards for diagnosis and management. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:3162-3167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Menezes N, Marson LP, debeaux AC, Muir IM, Auld CD. Prospective analysis of a scoring system to predict choledocholithiasis. Br J Surg. 2000;87:1176-1181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Nárvaez Rivera RM, González González JA, Monreal Robles R, García Compean D, Paz Delgadillo J, Garza Galindo AA, Maldonado Garza HJ. Accuracy of ASGE criteria for the prediction of choledocholithiasis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2016;108:309-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Yang MH, Chen TH, Wang SE, Tsai YF, Su CH, Wu CW, Lui WY, Shyr YM. Biochemical predictors for absence of common bile duct stones in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1620-1624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Peng WK, Sheikh Z, Paterson-Brown S, Nixon SJ. Role of liver function tests in predicting common bile duct stones in acute calculous cholecystitis. Br J Surg. 2005;92:1241-1247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |