Published online Apr 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i7.1257

Peer-review started: December 25, 2019

First decision: February 20, 2020

Revised: February 24, 2020

Accepted: March 22, 2020

Article in press: March 22, 2020

Published online: April 6, 2020

Processing time: 103 Days and 1.1 Hours

Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma (LELC) is a non-keratinizing carcinoma with rich lymphocytic infiltration, which primarily originates from the nasopharynx. Primary lung LELC is a type of lung cancer with a relatively low incidence. Herein, we report a rare case of lung LELC with expression of CD56. We also performed a literature review to summarize the epidemiological, clinical, and prognostic features of this disease.

A 51-year-old man was admitted to Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College due to cough and chest pain lasting > 2 mo and 1 wk, respectively. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging examinations revealed the presence of a mass in the right upper lobe with enlargement of lymph nodes and multiple bone metastases. According to the results of bronchoscopy and cervical lymph node biopsy, a diagnosis of lung LELC with CD56-positive staining (CD56+ lung LELC) was made. In the literature, 458 cases of lung LELC have been reported. However, only one other case of CD56+ lung LELC has been reported thus far.

The mechanism and potential role of CD56 expression in CD56+ lung LELC require further investigation.

Core tip: Primary lung lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma (LELC) is a rare type of lung carcinoma without established international diagnostic criteria. For this reason, misdiagnosis may occasionally occur and differential diagnosis with other lung primary carcinomas is required. Herein, we report a 51-year old man with CD56-positive lung LELC, which should be differentiated from large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. A total of 458 cases of lung LELC have been reported in the literature. This case is the second documented case of CD56-positive lung LELC. The mechanism and potential role of CD56 expression in lung LELC require further investigation.

- Citation: Yang L, Liang H, Liu L, Guo L, Ying JM, Shi SS, Hu XS. CD56+ lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the lung: A case report and literature review. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(7): 1257-1264

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i7/1257.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i7.1257

Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma (LELC) is a relatively rare type of non-keratinizing carcinoma characterized by prominent infiltration of lymphocytes. Although it primarily originates from the nasopharynx, rare cases occurring in other organs (e.g., the liver, breast, bladder, cervix, and lung) have also been previously reported[1-5]. Primary LELC of the lung was first described by Bégin et al[6] in 1987. This disease accounts for merely 0.92% of lung cancer cases and mostly affects the Asian population. According to the 4th edition of the World Health Organization classification of thymic tumors, LELC belongs to the category of “other and unclassified carcinoma”[7]. Owing to an insufficient number of cases, internationally recognized diagnostic criteria for LELC have not been established thus far. Misdiagnosis of LELC as adenocarcinoma or squamous carcinoma has been previously reported[8,9]. Following the introduction of the concept of precision medicine, clinicians and researchers have performed extensive investigations on the molecular profile of patients with lung LELC to facilitate differential diagnosis and personalized treatment. Herein, we report a rare case of lung LELC with CD56 expression. In addition, we systematically review the epidemiological, clinical, and prognostic features of lung LELC documented in the literature to better understand this rare disease.

A 51-year-old man presented to Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College in May 2017 with complaints of cough, expectoration, and chest pain.

The symptoms included cough and expectoration lasting > 2 mo and chest pain lasting 1 wk.

No past illnesses were documented.

The patient was a non-smoker without a family history of cancer.

Positive tenderness of the sternum, spine, and left femur was found during physical examination and the numerical rating scale score was 8.

The investigation of serum tumor markers showed that the cancer antigen 125, cytokeratin fragment antigen 21, and neuron-specific enolase were 37.7 U/mL, 13.68 ng/mL, and 76.71 ng/mL, with the corresponding upper limit of normal of 35 U/mL, 3.3 ng/mL, and 16.3 ng/mL, respectively.

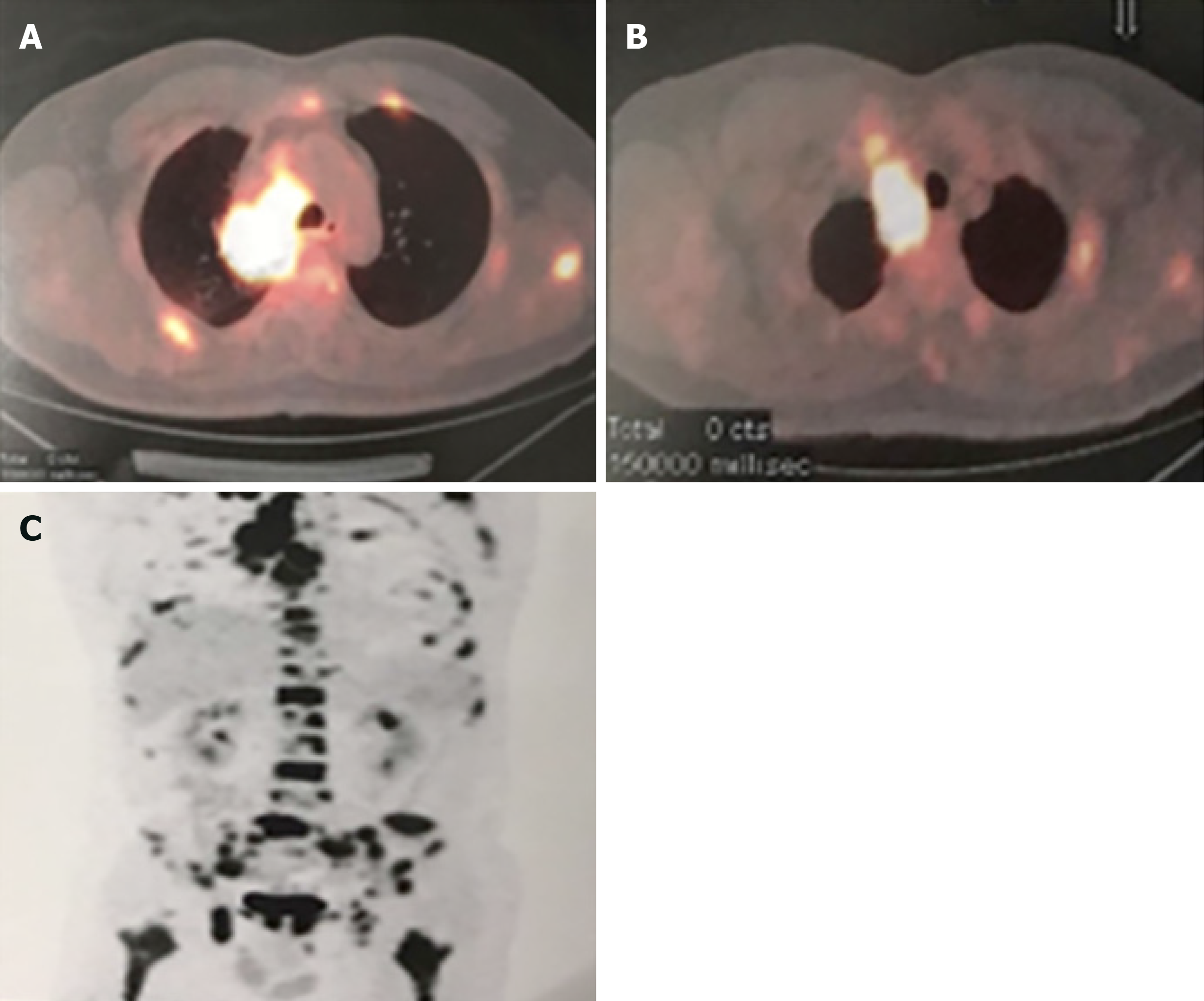

Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) revealed the presence of a mass (maximum diameter: 4.2 cm) in the right upper lobe, as well as enlarged lymph nodes and multiple metastases in the bilateral clavicles, mediastinum, and systemic skeleton (e.g., the head, chest, vertebra, and pelvis). The mass was adjacent to the mediastinal pleura and indistinct from the mediastinal enlarged lymph nodes, as well as the right lung hilum; the largest standardized uptake value was 18.4 (Figure 1A and B). Multiple bone metastases were illustrated through magnetic resonance imaging (Figure 1C). Pharyngorhinoscopy did not reveal abnormalities in the nasopharynx.

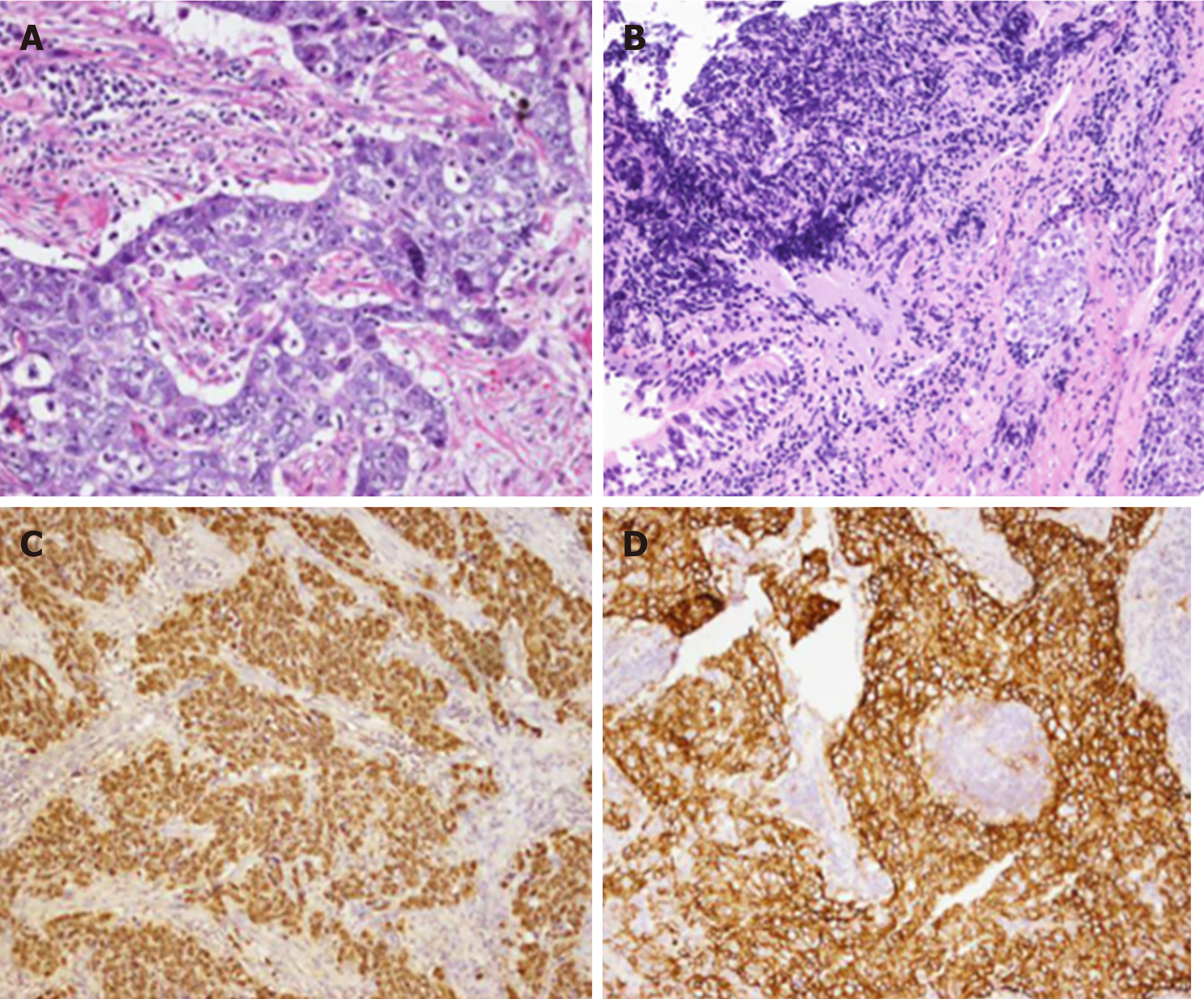

Bronchoscopic biopsy showed that a highly extruded heterotypic cell mass was present in the mucosal tissue that was overlain by ciliated columnar epithelia; this mass was considered a small-cell lung cancer. Bronchoscopic biopsy combined with immunohistochemistry (IHC) indicated poorly differentiated cancer with obviously extruded cells. Local extruded regions showed large cells with visible nucleoli. The IHC results were as follows: AE1/AE3 (1+), thyroid transcription factor 1 (−), CD56 (1+), chromaffin A (ChrA) (−), synaptophysin (Syn) (−), Ki-67 (+, > 75%), P63 (−), and P40 (−). Cervical lymph nodes were resected to reach a differential diagnosis. Microscopic examination showed that tumor cells were large with vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli, showing the typical morphological feature of LELC (Figure 2A and B). IHC staining demonstrated that the tumor cells were positive for AE1/AE3 (3+), cytokeratin 18 (2+), CK5/6 (focus+), P40 (focus+), P63 (focus+), CD56 (3+), ChrA (−), Syn (−), CK7 (−), Napsin A (−), ALK-VentanaD5F3 (−), ALK-Neg (−), and Ki-67 (+ > 75%) (Figure 2C). Encoded small nuclear RNA (EBER) was positive, suggesting infection with Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) (Figure 2D). There were no mutations detected in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and KRAS genes.

The final diagnosis was CD56-positive pulmonary LELC.

Prior to conducting the IHC staining, the EP regimen (cisplatin: 50 mg days 1 and 2, 40 mg day 3, intravenously guttae (ivgtt) /q21d + etoposide: 200 mg days 1–2, 100 mg day 3, ivgtt) was administered as first-line therapy since May 12, 2017 for the relief of whole body pain upon request by the patient.

After completion of two cycles of chemotherapy, CT showed that the size of the mass was reduced (largest diameter: 2.8 cm). Partial remission was achieved and whole body pain was obviously relieved with the reduction of the numerical rating scale to 2. After four cycles of chemotherapy, metastasis was observed in the level VI lymph nodes. Progression of disease was reported with a progression-free survival of 2.5 mo.

Primary LELC of the lung is a rare disease. A total of 138 articles were searched in PubMed using “lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma” and “pulmonary” as key words to comprehensively summarize the epidemiological, clinical, and prognostic characteristics of this condition. The available literature mainly included retrospective studies and individual reports, and no case-control studies. A total of 458 cases in ten high-quality publications with complete survival information were collected and analyzed as follows.

Epidemiologically, primary lung LELC is a rare malignant tumor. Since its first report in 1987[6], approximately 500 cases have been reported[9-11]. Approximately two-thirds of cases were documented in Southeast Asia, including southern China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and other regions. The incidence in males and females is similar and the average age at diagnosis is 54.4 years[12]. Approximately 75% of patients with primary lung LELC were non-smokers, suggesting that this disease is not associated with smoking[10]. It was reported that LELC is closely related to infection with EBV in the Asian population. The positive rate of EBV was 93.8% (30/32) in the Asian population compared with 0% (0/6) in the Western population[13,14]. In this case, the 51-year-old patient with positive EBV status was a non-smoker.

Compared with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), primary lung LELC is not characterized by special clinical manifestations. Of note, approximately 40% of the cases were asymptomatic. Dry cough, hemoptysis, chest pain, dyspnea, and other chest discomfort were the most commonly reported symptoms, while fever and weight loss were rare. Chest CT is the first choice for further examination. The mass of LELC was large in size and located near the mediastinum; some of the mass presented a tendency for vascular encasement[15,16]. PET-CT is another option for examination. The sensitivity of PET-CT in the diagnosis of lung LELC is 92.3% (12/13 cases), and its specificity is 66.7% (4/6 cases)[17]. In the present case, the patient presented to our hospital with cough and chest pain lasting > 2 mo and 1 wk, respectively. PET-CT revealed a mass adjacent to the mediastinal pleura in the right upper lobe, with a maximum diameter of 4.2 cm.

In terms of pathological characteristics and differential diagnosis, pulmonary LELC has a similar morphology to nasopharyngeal LELC. Microscopic observation revealed larger tumor cells with nest-like or syncytial distribution, slightly stained cytoplasm, and vesicular nuclei with eosinophilic prominent nucleoli. Pathological mitosis is common, and focal squamous and spindle cell differentiation can occur[18]. The IHC analysis showed that the tumor cells were primarily positive for CK5/6 and P63, with positive rates of 100% (11/11 cases) and 94% (15/16 cases), respectively[10]. The most important differential diagnosis of lung LELC is nasopharyngeal LELC with lung metastasis, owing to their almost identical morphologies. Clinical history and nasopharyngeal biopsy are helpful in differential diagnosis. In our case, pharyngorhinoscopy did not reveal abnormalities in the nasopharynx. The cell morphology and lymphocytic interstitial background were typical. IHC showed that CK5/6 and P63 were focally positive, supporting the diagnosis of LELC. However, CD56 showed strong positivity in this case. Therefore, the differentiation between LELC and large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) was the most challenging task in the present case.

LCNEC exhibits a neuroendocrine morphology, such as organoid nesting, trabecular growth, rosette-like structures, and peripheral palisading patterns. Solid nests with multiple rosette-like structures forming cribriform patterns are common. The tumor cells are generally large, with lightly-stained cytoplasm and prominent nucleoli. In addition, one or more indicators among ChrA, Syn, and CD56 are positive. CD56 showed lower specificity for neuroendocrine differentiation in lung cancer; however, it is the most sensitive marker in certain morphological context[19]. ChrA and Syn are the most reliable markers in distinguishing LCNEC from non-neuroendocrine tumors. Positive staining for either ChrA or Syn may be sufficient[20-23]. In our case, only CD56 was positive, whereas the other two endocrine markers were negative. The diagnosis of LCNEC was excluded considering the positivity for CD56 according to the 2015 definition of the World Health Organization[7] and the enhanced expression of EBER. In the literature, Jiang et al[24] previously reported a case of CD56-positive LELC. The present case was the second reported lung LELC with expression of CD56.

The genetic profile of lung LELC is very similar to that of EBV-associated tumors, such as nasopharyngeal carcinoma and natural killer/T-cell lymphoma. In contrast, it is markedly different from other primary lung tumors. The tumor protein p53 (TP53) mutation is the most frequent mutation in lung LELC (19.5%, 8/41 cases) and TNF receptor associated factor 3 (TRAF3) exhibits a high deletion rate (53.7%, 22/41 cases); these alterations are associated with a worse survival. The protein encoded by TRAF3 can inhibit the activation of nuclear factor-κB and the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. Moreover, it positively regulates the host innate immune response and T cell-dependent immune response, which may explain the specific infiltration of immunocytes observed in lung LELC. Of the cases, 19.5% (8/41 cases) showed amplification of the CD247 gene, which encodes the PD-L1 protein. This finding may be the dominant indicator for the use of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy in the treatment of lung LELC[25].

Owing to the low incidence of lung LELC, there is a lack of large-sample studies. Therefore, other therapeutic regimens against NSCLC and nasopharyngeal carcinoma were used as references. It is generally accepted that patients with early stage disease mainly undergo radical surgery, while those with locally advanced or advanced disease adopt the multi-disciplinary comprehensive treatment strategy (i.e., surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy). There are numerous chemotherapeutic regimens. Third-generation chemotherapeutic drugs, such as paclitaxel, gemcitabine, pemetrexed, and vinorelbine combined with platinum, fluorouracil, and capecitabine, are commonly used regimens. Han et al[26] reported five patients with LELC who underwent surgical resection of the lungs. Among them, the disease-free survival (DFS) in three patients was 5 years, and two patients had an overall survival of 45 months and 38 months. Fluorouracil combined with cisplatin was administered to seven patients with advanced lung LELC. The clinical partial remission rate was 71.4%[27]. After progression while receiving first-line therapy, monotherapy with capecitabine was effective as a rescue regimen[28]. In this case, although the initial EP regimen was effective, the remission time was short, suggesting that lung LELC may be more inclined to NSCLC rather than SCLC. This highlighted the need for additional experience to improve the treatment of similar cases.

The efficacy of tyrosine kinase inhibitors remains uncertain. It was reported that one case with an EGFR 21 exon L858R mutation progressed 1 mo after treatment with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor[29]. A study conducted in Taiwan found that the rate of EGFR mutation in primary lung LELC was only 12.1% (8/66 cases), and there were no abnormalities in the ALK and ROS1 genes[30]. In recent years, immunological checkpoint inhibitors have become a hot topic in the treatment of NSCLC. The positive rate of PD-L1 expression in patients with lung LELC is between 63.3% (50/79 cases) and 74.3% (84/113 cases)[31,32].

Comprehensive treatment in patients with high expression of PD-L1 was more effective than in those with low expression in terms of progression-free survival and overall survival (P = 0.019 and P = 0.042, respectively)[33]. However, postoperative DFS was worse in patients with high expression of PD-L1 than in those with low expression (5-year DFS: 48.3% vs 61.2%, respectively, P = 0.008)[32]. In 2016, the Cancer Research Center of the American Cancer Institute published its first report on the treatment of advanced lung LELC with nivolumab (3 mg/kg, every 2 wk)[34]. However, 10 days after the first administration of the drug, patients developed treatment-associated pneumonia, and liver and lung metastases progressed. The patients received medication for the second time to exclude pseudo-progression; however, the patients expired due to immune-associated enteritis and persistent progression of the lesions. This suggests extensive heterogeneity in the immune function of patients with primary lung LELC, which requires further investigation.

The prognosis of lung LELC is generally better than that of the other types of NSCLC. Early stage of disease, absence of lymph node metastasis, complete resection, and normal levels of lactate dehydrogenase and albumin are good prognostic factors. In contrast, age > 65 years is associated with a poor prognosis (hazard ratio: 2.685, 95% confidence interval: 1.052–6.853, P = 0.039)[10,35].

We report the diagnosis and therapy of a patient with CD56-positive lung LELC, and performed a literature review regarding this rare type of tumor. The diagnosis of primary lung LELC was reached through imaging examination, lymph node biopsy, and IHC analysis. Although the tumor exhibited positivity for CD56, LCNEC was excluded based on the expression of EBER and the diagnostic criteria of the disease. The molecular mechanism of diffuse positive expression of CD56 warrants further investigation.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Lin JA S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Liu MY

| 1. | Solinas A, Calvisi DF. Lessons from rare tumors: hepatic lymphoepithelioma-like carcinomas. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:3472-3479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Top ÖE, Vardar E, Yağcı A, Deniz S, Öztürk R, Zengel B. Lymphoepithelioma-like Carcinoma of the Breast: A Case Report. J Breast Health. 2014;10:177-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Laforga JB, Gasent JM. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the urinary bladder: A case report. Rev Esp Patol. 2017;50:54-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Philippe A, Rassy M, Craciun L, Naveaux C, Willard-Gallo K, Larsimont D, Veys I. Inflammatory Stroma of Lymphoepithelioma-like Carcinoma of the Cervix: Immunohistochemical Study of 3 Cases and Review of the Literature. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2018;37:482-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lin L, Lin T, Zeng B. Primary lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the lung: An unusual cancer and clinical outcomes of 14 patients. Oncol Lett. 2017;14:3110-3116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bégin LR, Eskandari J, Joncas J, Panasci L. Epstein-Barr virus related lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of lung. J Surg Oncol. 1987;36:280-283. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Travis WD, Brambilla E, Burke AP, Marx A, Nicholson AG. WHO classification of tumours of the lung, pleura, thymus and heart. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2015. |

| 8. | Jeong JS, Kim SR, Park SY, Chung MJ, Lee YC. A Case of Primary Pulmonary Lymphoepithelioma-like Carcinoma Misdiagnosed as Adenocarcinoma. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul). 2013;75:170-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Liang Y, Shen C, Che G, Luo F. Primary pulmonary lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma initially diagnosed as squamous metaplasia: A case report and literature review. Oncol Lett. 2015;9:1767-1771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Liang Y, Wang L, Zhu Y, Lin Y, Liu H, Rao H, Xu G, Rong T. Primary pulmonary lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma: fifty-two patients with long-term follow-up. Cancer. 2012;118:4748-4758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ho JC, Wong MP, Lam WK. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the lung. Respirology. 2006;11:539-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chen FF, Yan JJ, Lai WW, Jin YT, Su IJ. Epstein-Barr virus-associated nonsmall cell lung carcinoma: undifferentiated "lymphoepithelioma-like" carcinoma as a distinct entity with better prognosis. Cancer. 1998;82:2334-2342. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Han AJ, Xiong M, Zong YS. Association of Epstein-Barr virus with lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the lung in southern China. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;114:220-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Castro CY, Ostrowski ML, Barrios R, Green LK, Popper HH, Powell S, Cagle PT, Ro JY. Relationship between Epstein-Barr virus and lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the lung: a clinicopathologic study of 6 cases and review of the literature. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:863-872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ma H, Wu Y, Lin Y, Cai Q, Ma G, Liang Y. Computed tomography characteristics of primary pulmonary lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma in 41 patients. Eur J Radiol. 2013;82:1343-1346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wu J, Lu AD, Zhang LP, Zuo YX, Jia YP. [Study of clinical outcome and prognosis in pediatric core binding factor-acute myeloid leukemia]. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2019;40:52-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chan HY, Tsoi A, Wong MP, Ho JC, Lee EY. Utility of 18F-FDG PET/CT in the assessment of lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma. Nucl Med Commun. 2016;37:437-445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Butler AE, Colby TV, Weiss L, Lombard C. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the lung. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:632-639. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Lantuéjoul S, Laverrière MH, Sturm N, Moro D, Frey G, Brambilla C, Brambilla E. NCAM (neural cell adhesion molecules) expression in malignant mesotheliomas. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:415-421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Iyoda A, Travis WD, Sarkaria IS, Jiang SX, Amano H, Sato Y, Saegusa M, Rusch VW, Satoh Y. Expression profiling and identification of potential molecular targets for therapy in pulmonary large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. Exp Ther Med. 2011;2:1041-1045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Rossi G, Marchioni A, Milani M, Scotti R, Foroni M, Cesinaro A, Longo L, Migaldi M, Cavazza A. TTF-1, cytokeratin 7, 34betaE12, and CD56/NCAM immunostaining in the subclassification of large cell carcinomas of the lung. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122:884-893. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Rossi G, Mengoli MC, Cavazza A, Nicoli D, Barbareschi M, Cantaloni C, Papotti M, Tironi A, Graziano P, Paci M, Stefani A, Migaldi M, Sartori G, Pelosi G. Large cell carcinoma of the lung: clinically oriented classification integrating immunohistochemistry and molecular biology. Virchows Arch. 2014;464:61-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Travis WD, Rush W, Flieder DB, Falk R, Fleming MV, Gal AA, Koss MN. Survival analysis of 200 pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors with clarification of criteria for atypical carcinoid and its separation from typical carcinoid. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:934-944. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Jiang WY, Wang R, Pan XF, Shen YZ, Chen TX, Yang YH, Shao JC, Zhu L, Han BH, Yang J, Zhao H. Clinicopathological features and prognosis of primary pulmonary lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8:2610-2616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hong S, Wu K, Liu D, Fang W, Zhang L. Whole genome sequencing (WGS) to reveal the distinct genomic landscape of pulmonary lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma (LELC). J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1530 [DOI:. |

| 26. | Han AJ, Xiong M, Gu YY, Lin SX, Xiong M. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the lung with a better prognosis. A clinicopathologic study of 32 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2001;115:841-850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ho JC, Lam WK, Wong MP, Wong MK, Ooi GC, Ip MS, Chan-Yeung M, Tsang KW. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the lung: experience with ten cases. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004;8:890-895. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Ho JC, Lam DC, Wong MK, Lam B, Ip MS, Lam WK. Capecitabine as salvage treatment for lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of lung. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:1174-1177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Wang L, Lin Y, Cai Q, Long H, Zhang Y, Rong T, Ma G, Liang Y. Detection of rearrangement of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) and mutation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) in primary pulmonary lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7:1556-1562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Chang YL, Yang CY, Lin MW, Wu CT, Yang PC. PD-L1 is highly expressed in lung lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma: A potential rationale for immunotherapy. Lung Cancer. 2015;88:254-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Jiang L, Wang L, Li PF, Zhang XK, Chen JW, Qiu HJ, Wu XD, Zhang B. Positive expression of programmed death ligand-1 correlates with superior outcomes and might be a therapeutic target in primary pulmonary lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;8:1451-1457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Fang W, Hong S, Chen N, He X, Zhan J, Qin T, Zhou T, Hu Z, Ma Y, Zhao Y, Tian Y, Yang Y, Xue C, Tang Y, Huang Y, Zhao H, Zhang L. PD-L1 is remarkably over-expressed in EBV-associated pulmonary lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma and related to poor disease-free survival. Oncotarget. 2015;6:33019-33032. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Jiang L, Wang L, Li PF, Zhang XK, Chen JW, Qiu HJ, Wu XD, Zhang B. Positive Expression of Programmed Death ligand-1 Correlates With Superior Outcomes and Might Be a Therapeutic Target in Primary Pulmonary Lymphoepithelioma-Like Carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;8:1451-1457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Kim C, Rajan A, DeBrito PA, Giaccone G. Metastatic lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the lung treated with nivolumab: a case report and focused review of literature. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2016;5:720-726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | He J, Shen J, Pan H, Huang J, Liang W, He J. Pulmonary lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma: a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database analysis. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7:2330-2338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |