Published online Mar 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i6.1172

Peer-review started: November 13, 2019

First decision: February 20, 2020

Revised: February 27, 2020

Accepted: March 5, 2020

Article in press: March 5, 2020

Published online: March 26, 2020

Processing time: 133 Days and 14.1 Hours

The incidence of short stature in KBG syndrome is relatively high. Data on the therapeutic effects of growth hormone (GH) on children with KBG syndrome accompanied by short stature in the previous literature has not been summarized.

Here we studied a girl with KBG syndrome and collected the data of children with KBG syndrome accompanied by short stature from previous studies before and after GH therapy. The girl was referred to our department because of short stature. Physical examination revealed mild dysmorphic features. The peak GH responses to arginine and clonidine were 6.22 and 5.40 ng/mL, respectively. The level of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) was 42.0 ng/mL. Genetic analysis showed a c.2635 dupG (p.Glu879fs) mutation in the ANKRD11 gene. She received GH therapy. During the first year of GH therapy, her height increased by 0.92 standard deviation score (SDS). Her height increased from -1.95 SDS to -0.70 SDS after two years of GH therapy. There were ten children with KBG syndrome accompanied by short stature who received GH therapy in reported cases. Height SDS was improved in nine (9/10) of them. The mean height SDS in five children with KBG syndrome accompanied by short stature increased from -2.72 ± 0.44 to -1.95 ± 0.57 after the first year of GH therapy (P = 0.001). There were no adverse reactions reported after GH treatment.

GH treatment is effective in our girl and most children with KBG syndrome accompanied by short stature during the first year of therapy.

Core tip: KBG syndrome is a rare autosomal dominant disorder. The percentage of height below 10th centile is relatively high at 66%. Children with KBG syndrome accompanied by short stature could benefit from growth hormone therapy.

- Citation: Ge XY, Ge L, Hu WW, Li XL, Hu YY. Growth hormone therapy for children with KBG syndrome: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(6): 1172-1179

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i6/1172.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i6.1172

KBG syndrome (OMIM 148050) is a rare autosomal dominant disorder first reported by Herrmann et al[1] in 1975. They described seven affected individuals from three unrelated families. The KBG syndrome was named after the surname initials K, B, and G of the three original families. It is characterized by developmental delay, intellectual disability, specific craniofacial features, macrodontia of the upper central incisors, short stature, and skeletal abnormalities[2]. KBG syndrome is caused by mutations in the ANKRD11 gene located on chromosome 16q24.3, which encodes an ankyrin repeat domain-containing cofactor[3]. Over 110 cases have been reported in the literature so far[4]. KBG syndrome should be distinguished from 16q24.3 microdeletion syndrome. Although the clinical manifestations of these two syndromes overlap, there are some differences in phenotypes. In 16q24.3 microdeletion syndrome, short stature and delayed bone age are often not observed[5].

Low et al[2] described 31 patients affected by KBG syndrome with ANKRD11 gene mutation in 2016. They proposed new diagnostic criteria for KBG syndrome. The major criteria included macrodontia (85%), height below the 10th centile (66%), recurrent otitis media and/or hearing loss (44%), and 1st-degree relatives with KBG syndrome (22%). The minor criteria included brachydactyly (50%), seizures (43%), cryptorchidism (31%), feeding problems (34%), palate abnormality (25%), autism (24%), and delayed closure of the anterior fontanelle (22%). KBG syndrome can be diagnosed in patients with developmental delay/learning difficulties, speech delay, or significant behavioural issues, with at least two major criteria or one major and two minor criteria.

There are no specific treatments for KBG syndrome. Based on their complex clinical symptoms, genetics, neurology, cardiology, endocrinology, surgery, rehabilitation medicine, and education need to be involved in the treatment in the form of multi-disciplinary team[2]. The incidence of short stature in KBG syndrome is relatively high. The effects of growth hormone (GH) therapy on children with KBG syndrome accompanied by short stature are not clear. It has been reported that two children with KBG syndrome showed a good response to GH therapy. They almost reached their parental target height after 3 and 5 years of GH therapy, respectively[6]. Further study was needed to determine whether GH may be successful in treating children with KBG syndrome accompanied by short stature. Data on the therapeutic effects of GH on children with KBG syndrome accompanied by short stature in previous studies have not been summarized. Therefore, we report our experience with one girl with KBG syndrome and collected the data of children with KBG syndrome accompanied by short stature from previous studies before and after GH therapy to provide evidence for the effect of GH treatment in children with KBG syndrome accompanied by short stature.

A Chinese girl aged 5 years and 6 mo presented to the Pediatric Department of our hospital complaining of short stature.

The girl was born at term as the only child of her parents. Her birth weight was 3400 g [0.58 standard deviation score (SDS)], and her length was 50 cm (0.1 SDS). Pregnancy, delivery, and the neonatal period were uncomplicated. At 2 mo of age, a developmental delay was found by regular physical examination. She received rehabilitation therapy for 4 mo intermittently. She started walking at 17 mo of age and spoke her first words at 12 mo. Her height was below the mean for age (less than the 3rd percentile). Ordinarily, she was quiet, short-tempered, and irritable.

Her past medical history was unremarkable except for developmental delay.

No specific personal history of disease was recorded. Her parents were healthy, with no significant family history. Her mother’s height was 160 cm, and his father’s height was 171 cm. The target height for the proband was 159.0 cm (-0.30 SDS).

Her height was 104.7 cm (-1.95 SDS). Her weight was 15.5 kg. Her head circumference was 57.9 cm (+0.3 SDS). Physical examination revealed mild dysmorphic features, including a long triangular face, frontal bossing, large and protruding ears, broad eyebrows, a high nasal bridge, a long philtrum, macrodontia of the central incisors, and brachydactyly. No significant hearing loss or palate abnormalities were found.

After two stimulation tests (arginine test and levodopa test), the peak GH responses to arginine and levodopa were 6.22 ng/mL and 5.40 ng/mL, respectively. The cut-off peak GH value for GH deficiency was ≤ 10 ng/mL. GH deficiency was confirmed. Serum GH level was measured using chemiluminescence assay (Cobas E170, Roche Diagnostics, Germany). The level of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) was 42.0 ng/mL. Serum IGF-1 were measured using chemiluminescence assay (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, USA). Other biochemical examinations, such as of thyroid function, sex hormones, adrenal function, and blood glucose, were normal.

Written informed consent for clinical whole-exome detection was obtained from her parents. Clinical whole-exome detection was offered by Sino-Science in Beijing, China.

Her bone age was 4.5 years. Bone age was estimated using the atlas of Greulinch-pyle. Pituitary magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and echocardiography were normal.

She had a borderline intellectual disability with a total IQ of 79 (WISC-R).

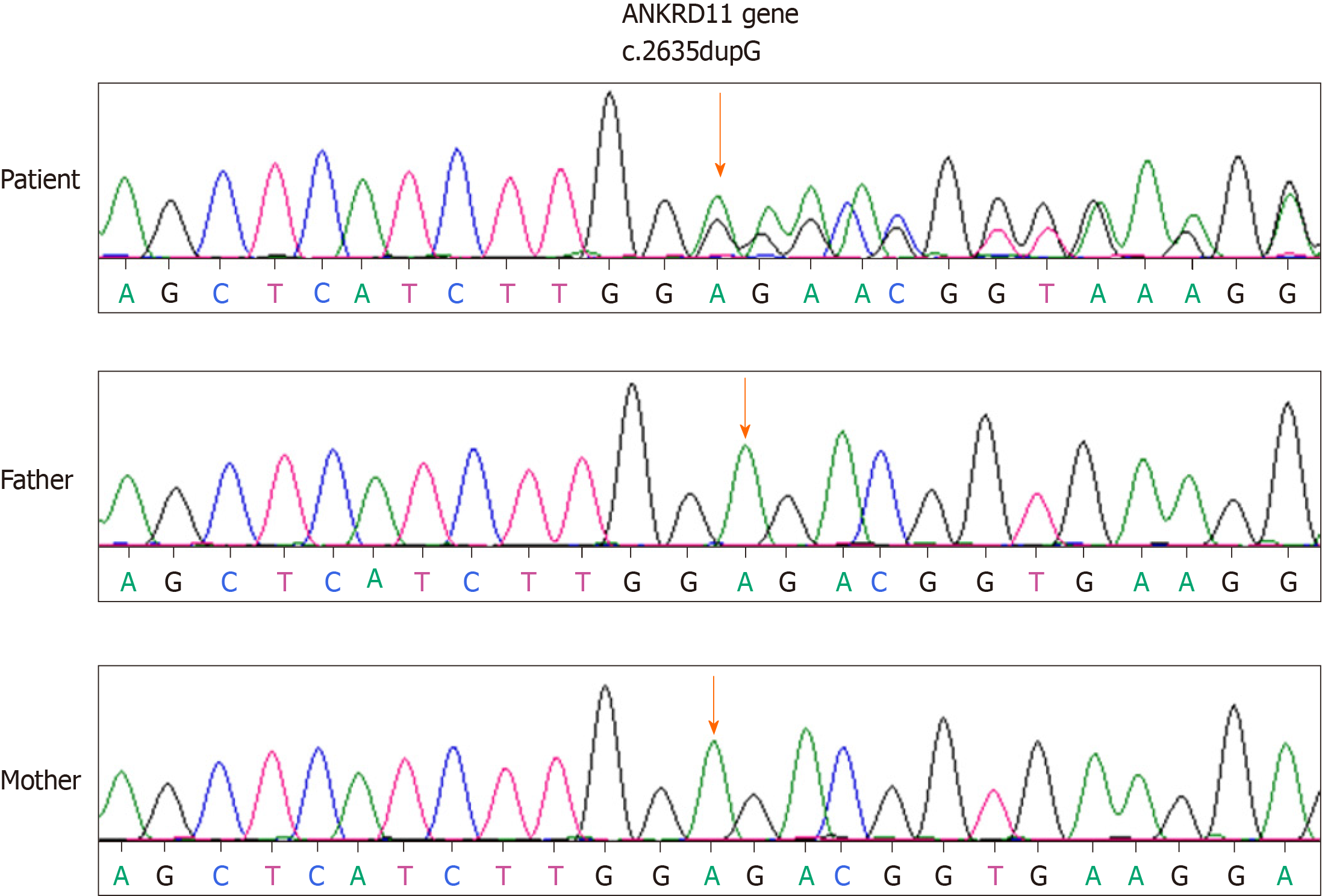

A novel de novo mutation (c.2635 dupG, p.Glu879fs) was identified in the ANKRD11 gene. The variant was interpreted as pathogenic based upon the de novo variant in a family without a disease history (PS2) according to the guidelines of ACMG. KBG syndrome was confirmed. Sanger sequencing was employed for our girl and her parents (Figure 1). No mutation of the ANKRD11 gene was present in her parents.

The patient was treated with recombinant human GH injections (50 μg/kg/d, GenSci, Changchun, Jilin Province) starting at age 5 years and 6 mo.

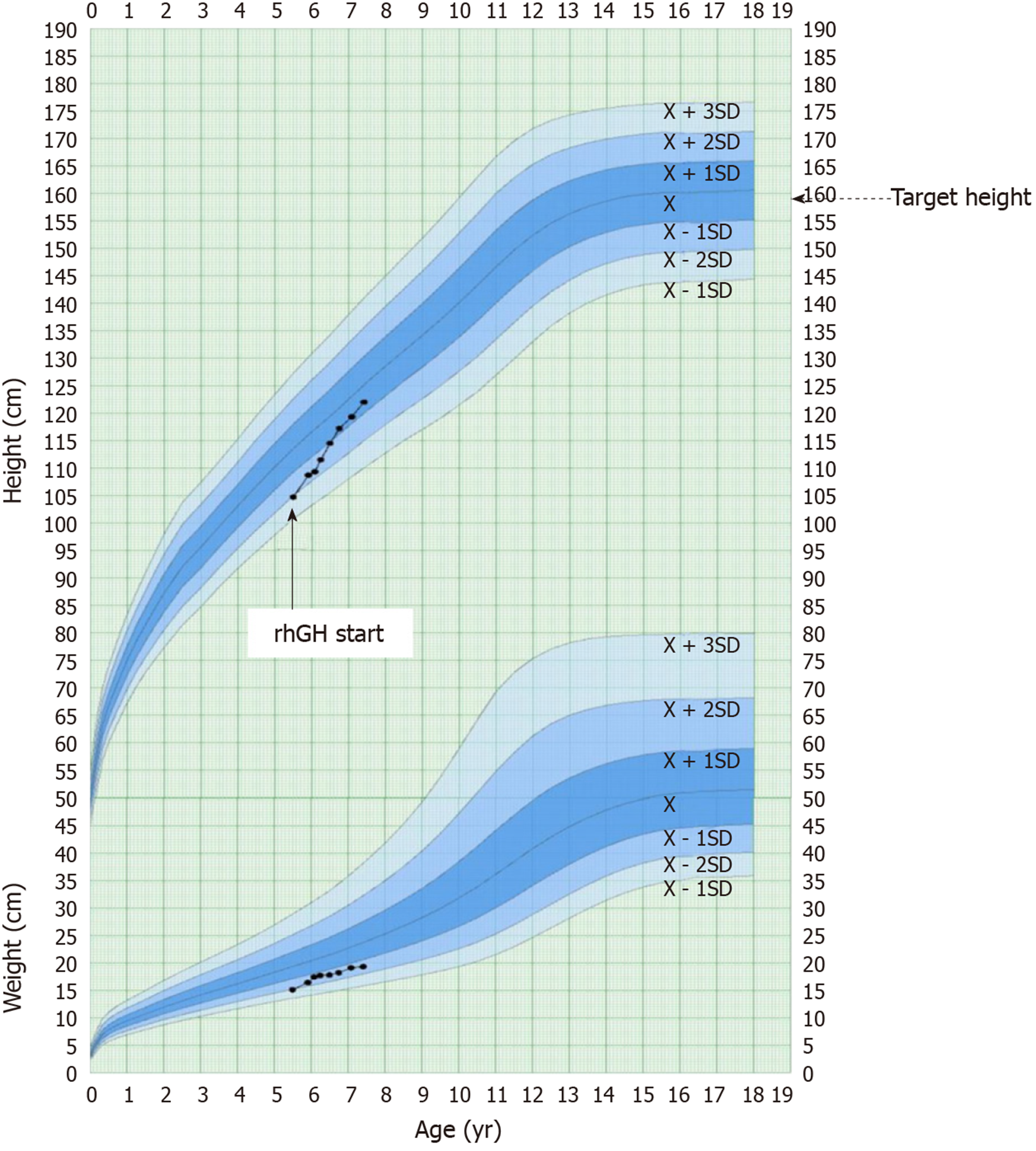

Follow-up was performed every 3 mo for two years. During the first year of GH therapy, her height increased by 0.92 SDS. Over the two years of GH, her height increased from -1.95 SDS to -0.70 SDS (Figure 2). Thyroid function and blood glucose were normal during the two-year follow-up.

In this study, we collected the data of children with KBG syndrome accompanied by short stature. To observe the effects of GH therapy on the height of children with KBG syndrome accompanied by short stature, we mainly analyzed growth velocity during the first year by comparing those with and those without GH therapy.

Children with KBG syndrome accompanied by short stature without description of changes in height were excluded from our research. A total of ten children with KBG syndrome accompanied by short stature who received GH therapy (P1-P10) were included[4,6-10]. Three children with KBG syndrome accompanied by short stature who did not receive GH therapy (P11, P12, and P13) were also included[5,11].

Clinical features of children with KBG syndrome accompanied by short stature who received GH therapy are shown in Table 1 (P1-P8). P8 is our patient. Two children (P9 and P10) without detailed clinical information are not shown in Table 1. The birth length in three (3/5) children was below the 50th percentile. Height SDS was below the 3rd percentile in all children (10/10). GH deficiency was suggested in four (4/6) children. Levels of IGF-1 were low in three (3/4) children. Delayed bone age was found in six (6/8) children.

| Case | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | P8 |

| Gender | Male | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Female |

| Country | Sweden | Sweden | China | Australia | Australia | Italy | Italy | China |

| Pregnancy complication | Normal | Polyhydramnios | Normal | Advanced maternal age | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| Gestational age | 38.5 wk | 40 wk and 6 d | Full term | 40 wk | 32 wk | Full term | Full term | Full term |

| Delivery | Breech presentation | Normal | Vaginal delivery | Vaginal delivery; Fetal distress and meconium liquor | Cesarean section | Cesarean section | Cesarean section | Vaginal delivery |

| Birth length, cm | 47 (–1.5 SDS) | 50 (–0.5 SDS) | 48 (-0.90 SDS) | 50th | NA | NA | NA | 50 (0.1 SDS) |

| Birth weight, g | 2940 (–0.6 SDS) | 3945 (1 SDS) | 2400 (-2.19 SDS) | NA (< 10th) | NA (90th) | NA | NA | 3400 (0.58 SDS) |

| Referred age, yr | 5.5 | 7 | 7.6 | 15 | 4 | 9 | 4 | 5.5 |

| Chief complain | Short stature | Short stature | Short stature | NA | NA | NA | NA | Short stature |

| Height SDS | -2.4 SDS | –2.8 SDS | -2.82 SDS | < -1.88 SDS | < -1.88 SDS | -2.58 SDS | -3.25 SDS | -1.95 SDS |

| Midparental height | -1.2 SDS | –0.3 SDS | -1.6 SDS | NA | NA | NA | NA | -1.6 SDS |

| Peak GH | 40.3 mU/L | 10 mU/L (GH deficit) | 5.7 ng/mL | NA | NA | No GH deficit | 5.1 ng/mL | 6.22 ng/mL |

| IGF-1 | 88 ng/mL | 51, 76, and 56 ng/mL | 271 ng/mL | NA | NA | NA | NA | 42 ng/mL |

| Thyroid function | Normal | Normal | Normal | NA | NA | Subclinical hypothyroidism | Small thyroid | Normal |

| Delayed bone age, yr | Delayed 3.0 | Delayed 1.5 | Delayed 3.6 | Yes | No | Yes | No | Delayed 1.0 |

| Pituitary MRI /Brain imaging | NA | Normal | Normal | NA | Neonatal seizures; Multiple calcific foci in brain; Arachnoid cyst; Germinolytic cysts | Unspecific structural abnormalities | Enlarged cisterna magna; Leptomeningeal cyst | Normal |

| GH therapy started age | 10.5 yr | 7.4 yr | 7.9 yr | 15 yr | Not known | 11 yr | 5.2 yr | 5.5 yr |

| Height SDS | -3.1 SDS | –2.8 SDS | -2.87 SDS | < -1.88 SDS | Not known | -2.86 SDS | -2.87 SDS | -1.95 SDS |

| GH dose | 35 μg/kg/d | 30 μg/kg/d | 52 μg/kg/d | NA | NA | NA | NA | 50 μg/kg/d |

| Others | Triptorelin was added at 12.5 yr | No | Intermittent treatment | No | No response to rhGH therapy | No | No | No |

| ANKRD11 aberrations | c.3836del (p.Ser1279fs) | c.1903_1907del(p.Lys635Glnfs * 26) | c.6972dupc (p.p2271pfs*8) | No genetic testing | c.6472G > T (p.Glu2158) | c.7534C > T (p.Arg2512Trp) | c.3339G > A (p.Trp1113Ter) | c.2635 dupG (p.Glu879fs) |

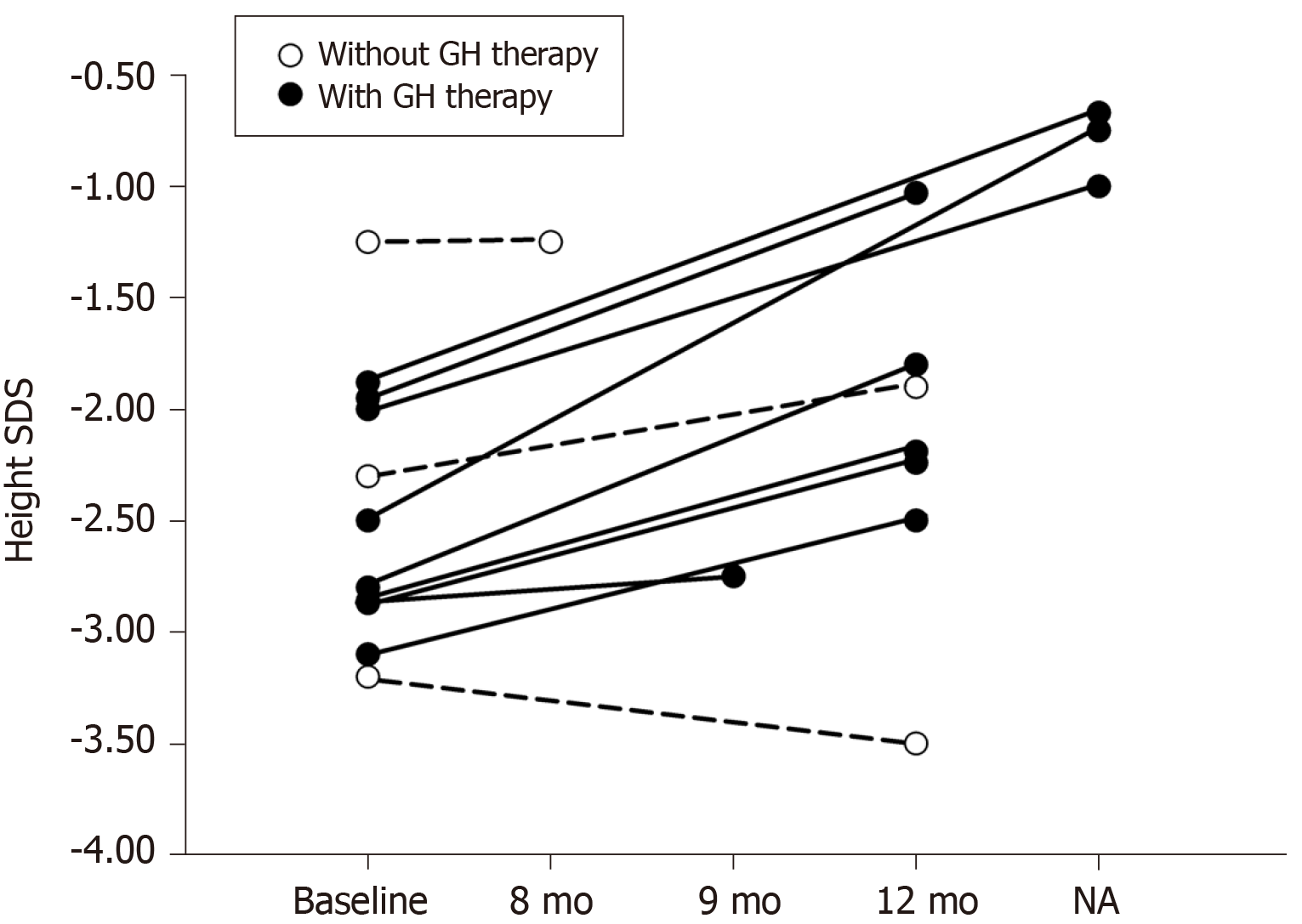

In children with KBG syndrome accompanied by short stature who received GH therapy (P1-P10), Patient 5 showed no response to GH therapy, though specific height velocity data were missing. The authors did not explain why the child showed no response. The height velocities of children with KBG syndrome accompanied by short stature who received GH therapy (P1-P4 and P6-10) were compared with those who did not receive GH therapy (P11, P12, and P13). Among them, Patient 3 was followed for 9 mo, Patient 13 was followed for 8 mo, and three patients (P4, P9, and P10) were followed for an unspecified time. Their height changes are shown in Figure 3. Height SDS was improved in nine (9/10) children with KBG syndrome accompanied by short stature after GH therapy. The mean height SDS in five children with KBG syndrome accompanied by short stature (P1, P2, and P6-8) increased from -2.72 ± 0.44 to -1.95 ± 0.57 after the first year of GH therapy (P = 0.001). In children with KBG syndrome accompanied by short stature who did not receive GH therapy, height SDS did not change in 8 mo (from -1.25 to -1.25) in P13, increased mildly (from -2.3 to -1.9) in the first year in P12, and decreased (from -3.2 to -3.5) in approximately one year in P11. The dosages of GH were not given in the literature. There were no adverse reactions (such as hypothyroidism, hyperglycemia, intracranial hypertension, and scoliosis) reported after GH treatment.

The use of GH therapy obviously promoted growth in the girl with KBG syndrome accompanied by short stature. There were no abnormalities in thyroid function or glycemic status during the two years of follow-up. In the previous literature, most children with KBG syndrome showed a good response to the first year of GH therapy compared with untreated children affected by KBG syndrome. Our results are consistent with other reported cases[6]. Based on the review of previously reported cases and the experience obtained from our KBG case, we conclude that GH treatment is effective in our girl and most children with KBG syndrome accompanied by short stature during the first year of therapy.

It was reported[9] that only one child with KBG syndrome was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia. Down-regulation of the ANKRD11 gene might be associated with breast cancer[12]. The ANKRD11 gene was found to enhance the transcription of p53, as ANKRD11 was thought to be a p53 coactivator[13]. However, the role of the ANKRD11 gene in cancer was not confirmed[8]. Therefore, we need further evidence from long-term follow-up and close monitoring for tumors during GH therapy in patients with KBG syndrome. There is a pressing need to establish guidelines for GH therapy in patients with KBG syndrome.

This study had several limitations, such as incomplete data and short-term follow-up. The long-term effects of GH therapy on children with KBG syndrome and its benefits to adult height are not clear. A large-scale case-control and long-term follow-up study is necessary to better understand the effects of GH therapy on children with KBG syndrome accompanied by short stature.

In conclusion, our girl with KBG syndrome showed a good growth response to the first year of GH therapy. We reviewed and analyzed the changes in the height of children with KBG syndrome accompanied by short stature during the first year of therapy in the reported cases. We conclude that GH treatment is effective in our girl and most children with KBG syndrome accompanied by short stature during the first year of therapy. Our results provide evidence for GH treatment in children with KBG syndrome accompanied by short stature.

The authors are grateful to the patient and her parents for participating in the study.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Lee AC, Al-Biltagi M S-Editor: Wang YQ L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Qi LL

| 1. | Herrmann J, Pallister PD, Tiddy W, Opitz JM. The KBG syndrome-a syndrome of short stature, characteristic facies, mental retardation, macrodontia and skeletal anomalies. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1975;11:7-18. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Low K, Ashraf T, Canham N, Clayton-Smith J, Deshpande C, Donaldson A, Fisher R, Flinter F, Foulds N, Fryer A, Gibson K, Hayes I, Hills A, Holder S, Irving M, Joss S, Kivuva E, Lachlan K, Magee A, McConnell V, McEntagart M, Metcalfe K, Montgomery T, Newbury-Ecob R, Stewart F, Turnpenny P, Vogt J, Fitzpatrick D, Williams M; DDD Study, Smithson S. Clinical and genetic aspects of KBG syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2016;170:2835-2846. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sirmaci A, Spiliopoulos M, Brancati F, Powell E, Duman D, Abrams A, Bademci G, Agolini E, Guo S, Konuk B, Kavaz A, Blanton S, Digilio MC, Dallapiccola B, Young J, Zuchner S, Tekin M. Mutations in ANKRD11 cause KBG syndrome, characterized by intellectual disability, skeletal malformations, and macrodontia. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89:289-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Li QY, Yang L, Wu J, Lu W, Zhang MY, Luo FH. A case of KBG syndrome caused by mutation of ANKRD11 gene and literature review. Clin J Evid Based Pediatr. 2018;13:452-458. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Khalifa M, Stein J, Grau L, Nelson V, Meck J, Aradhya S, Duby J. Partial deletion of ANKRD11 results in the KBG phenotype distinct from the 16q24.3 microdeletion syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161A:835-840. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Reynaert N, Ockeloen CW, Sävendahl L, Beckers D, Devriendt K, Kleefstra T, Carels CE, Grigelioniene G, Nordgren A, Francois I, de Zegher F, Casteels K. Short Stature in KBG Syndrome: First Responses to Growth Hormone Treatment. Horm Res Paediatr. 2015;83:361-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Murray N, Burgess B, Hay R, Colley A, Rajagopalan S, McGaughran J, Patel C, Enriquez A, Goodwin L, Stark Z, Tan T, Wilson M, Roscioli T, Tekin M, Goel H. KBG syndrome: An Australian experience. Am J Med Genet A. 2017;173:1866-1877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Scarano E, Tassone M, Graziano C, Gibertoni D, Tamburrino F, Perri A, Gnazzo M, Severi G, Lepri F, Mazzanti L. Novel Mutations and Unreported Clinical Features in KBG Syndrome. Mol Syndromol. 2019;10:130-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Goldenberg A, Riccardi F, Tessier A, Pfundt R, Busa T, Cacciagli P, Capri Y, Coutton C, Delahaye-Duriez A, Frebourg T, Gatinois V, Guerrot AM, Genevieve D, Lecoquierre F, Jacquette A, Khau Van Kien P, Leheup B, Marlin S, Verloes A, Michaud V, Nadeau G, Mignot C, Parent P, Rossi M, Toutain A, Schaefer E, Thauvin-Robinet C, Van Maldergem L, Thevenon J, Satre V, Perrin L, Vincent-Delorme C, Sorlin A, Missirian C, Villard L, Mancini J, Saugier-Veber P, Philip N. Clinical and molecular findings in 39 patients with KBG syndrome caused by deletion or mutation of ANKRD11. Am J Med Genet A. 2016;170:2847-2859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ockeloen CW, Willemsen MH, de Munnik S, van Bon BW, de Leeuw N, Verrips A, Kant SG, Jones EA, Brunner HG, van Loon RL, Smeets EE, van Haelst MM, van Haaften G, Nordgren A, Malmgren H, Grigelioniene G, Vermeer S, Louro P, Ramos L, Maal TJ, van Heumen CC, Yntema HG, Carels CE, Kleefstra T. Further delineation of the KBG syndrome phenotype caused by ANKRD11 aberrations. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23:1176-1185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tekin M, Kavaz A, Berberoğlu M, Fitoz S, Ekim M, Ocal G, Akar N. The KBG syndrome: confirmation of autosomal dominant inheritance and further delineation of the phenotype. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;130A:284-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lim SP, Wong NC, Suetani RJ, Ho K, Ng JL, Neilsen PM, Gill PG, Kumar R, Callen DF. Specific-site methylation of tumour suppressor ANKRD11 in breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:3300-3309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Neilsen PM, Cheney KM, Li CW, Chen JD, Cawrse JE, Schulz RB, Powell JA, Kumar R, Callen DF. Identification of ANKRD11 as a p53 coactivator. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:3541-3552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |