Published online Mar 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i6.1137

Peer-review started: November 14, 2019

First decision: December 23, 2019

Revised: December 31, 2019

Accepted: January 19, 2020

Article in press: January 19, 2020

Published online: March 26, 2020

Processing time: 132 Days and 23.3 Hours

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) causes significant morbidity and mortality in diverse childhood diseases. However, limited information has been reported to obtain a good understanding of pediatric PH. Gaps exist between genome sequencing and metabolic assessments and lead to misinterpretations of the complicated symptoms of PH. Here, we report a rare case of a patient who presented with severe PH as the first manifestation without significant cardiovascular malformation and was finally diagnosed with methylmalonic aciduria (MMA) after metabolic and genomic assessments.

An 11-year-old female presented with an aggressive reduction in activity capability and shortness of breath for only 4 mo and suffered from unexplained PH. A series of examinations was performed to evaluate any possible malformations or abnormalities of the cardiovascular system and lungs, but negative results were obtained. The blood tests were normal except for manifestations of microcytic anemia and elevated total homocysteine. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging failed to identify any pulmonary diseases. Cardiac catheterization examination identified a small right coronary artery to pulmonary artery shunt and severe PH. During the follow-up, PH progressed rapidly. Then, genome sequencing and metabolic disorder screening were performed, which confirmed a diagnosis of MMA with MMACHC c.80A > G/c and 609G > A mutations. Vitamin B12, betaine and bosentan were then administered as the main treatments. During the 6-mo follow-up, the pulmonary artery pressure dropped to 45 mmHg, while the right ventricle structure recovered. The patient’s heart function recovered to NYHA class II. Metabolic disorder analysis failed to identify significant abnormalities.

As emerging types of metabolic dysfunction have been shown to present as the first manifestation of PH, and taking advantage of next generation sequencing technology, genome sequencing and metabolic disorder screening are recommended to have a more superior role when attempting to understand unclear or aggressive PH.

Core tip: This report describes a case who suffered an aggressive pulmonary hypertension (PH) as her first onset manifestation. Following the routine diagnostic and therapeutic procedure, we failed to address any abnormalities which could explain the origins of PH. However, taking the advantage of metabolic screening and genome sequencing, we achieved the diagnosis of methylmalonic acidemia and revealed that the severe PH is secondary to methylmalonic acidemia, which was not mentioned among several guidelines of PH. Although metabolic and genome screenings have been recommended in guideline, this case brought our reconsideration to the timing for perform metabolic and genomic screenings. So that, we would like to mention that for some aggressive unexplained PH patients who meets the criteria, such screening procedure should be applied in an earlier stage to prevent putting the patients into irreversible conditions.

- Citation: Liao HY, Shi XQ, Li YF. Metabolic and genetic assessments interpret unexplained aggressive pulmonary hypertension induced by methylmalonic acidemia: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(6): 1137-1141

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i6/1137.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i6.1137

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a progressive disease that causes significant morbidity and mortality in various childhood diseases[1]. In childhood, abnormal heart structures, especially left-to-right shunt congenital heart diseases, are the main causes of PH[2]. Despite the availability of new medications, the long-term outcomes are still poor[3]. Recently, emerging studies have reported that genetic and metabolic assessments have been performed to demonstrate the molecular basis of unexplained PH. However, it is unknown which patients need to receive a genomic and metabolic assessment. Here, we report a rare case of severe PH as the first manifestation in a patient who underwent a delayed genomic and metabolic assessment to accurately understand the disorder. In addition, we reconsidered the criteria for unexplained PH that indicate the need for a combined genomic and metabolic assessments.

An 11-year-old girl complained of an aggressive reduction in activity capability and shortness of breath and presented to our cardiovascular department.

The patient started to demonstrate a reduction in activity capability 4 mo ago and progressed with accelerated worsening of her condition within the most recent 1 mo, presenting severe shortness of breath. However, the patient denied any history of past illness.

An enhanced P2 sound and a systolic murmur between sternal ribs 2 and 3 were observed. She suffered from NYHA class II heart function. Echocardiography revealed a large right ventricle and pulmonary artery trunk, with an estimated 60 mmHg pulmonary arterial pressure and normal left heart function. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging scans excluded lung disease and cardiomyopathy, which could lead to PH. In addition, the results of the autoimmune antibody analysis were negative and excluded any connective tissue or rheumatological diseases.

The right ventricular catheter examination showed an elevated right ventricular pressure of 50/2 (23) mmHg, main pulmonary artery pressure of 57/21 (55) mmHg, left pulmonary artery pressure of 50/29 (36) mmHg and right pulmonary artery pressure of 60/31 (45) mmHg with a total pulmonary resistance of 8.72 woods, Qp 6.3 L/min. Therefore, the catheter evaluation failed to identify a clear cause.

Because of the rapid progression of pulmonary artery pressure with microcytic anemia and elevated homocysteine, metabolic disorders were suspected. Therefore, metabolic screening and genome sequencing was performed for this patient. Metabolic screening showed an elevation of methylmalonic acid of 51.82 µg/L, and two mutations c.80A > G/c and 609G > A were recognized at the gene for methylmalonic aciduria and homocystinuria type C protein (MMACHC), and these mutations were reported to be associated with methylmalonic acidemia, cobalamin C type.

This patient was finally diagnosed with methylmalonic acidemia with aggressive PH as the first clinical manifestation.

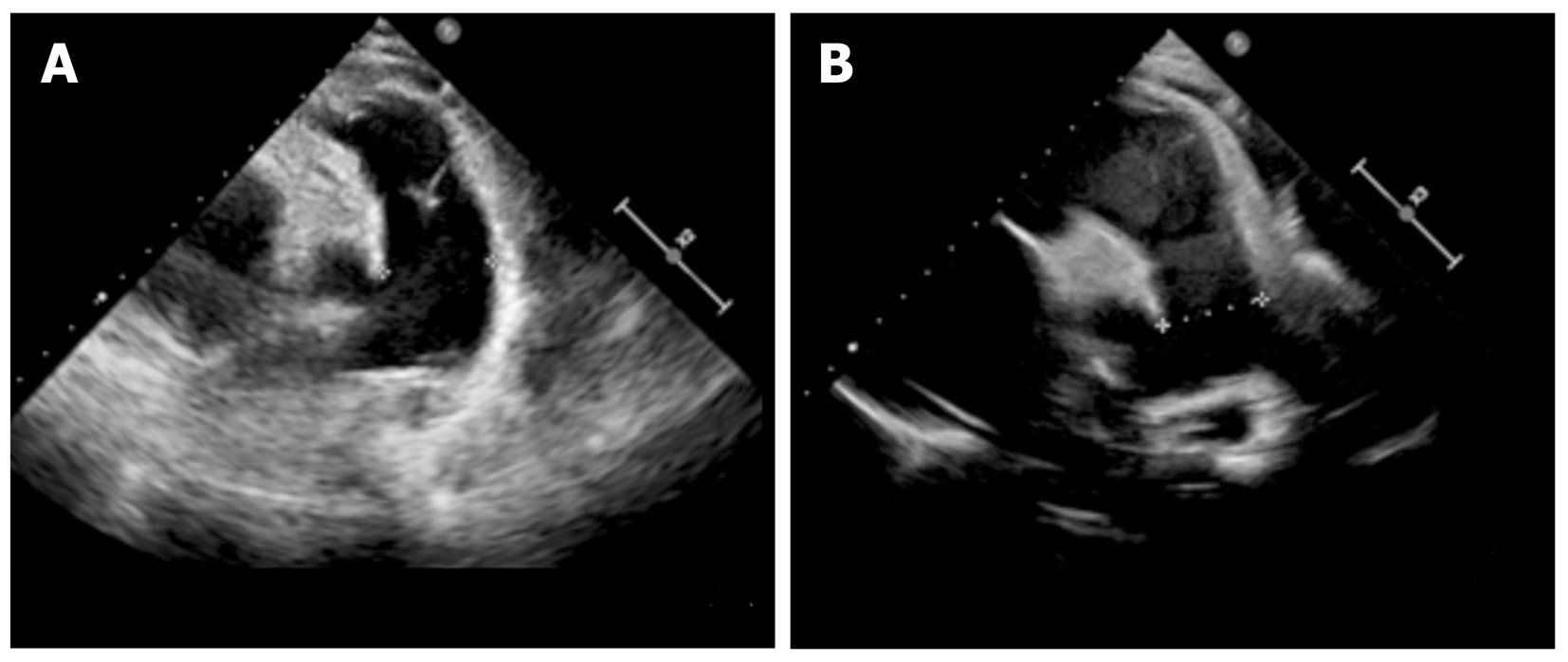

As metabolic and genome screening need almost 1 mo to be completed, we provided bosentan (endothelin-1 inhibitor) to this patient and performed frequent follow-up assessments while waiting for results. However, after 1 mo, the patient presented with aggressive worsening of the clinical manifestations. Her heart function worsened to NYHA class IV. The laboratory test demonstrated microcytic anemia with increasing brain natriuretic peptide as high as 3939.23 pg/mL (nv < 100) and total homocysteine as high as 119.99 µmol/L (nv < 15). Echocardiography revealed that the pulmonary artery pressure was elevated to 70 mmHg, with a right ventricular Tei index of 0.8, and her pulmonary artery size increased to 30 mm. According to the screening results, a diagnosis of methylmalonic acid was reached. Vitamin B12 (1 mg/d) and betaine (200 mg/kg/day) were immediately administered as supplemental therapy with bosentan. After 6 mo of treatment with vitamin B12 and betaine, her pulmonary artery hypertension decreased to 45 mmHg, right ventricular Tei-index dropped to 0.29, and pulmonary artery size decreased to 25 mm, according to the latest echocardiography (Figure 1). Her heart function reversed to NYHA class II. The metabolic disorder analysis failed to identify abnormalities, and a methylmalonic acid level of 6.53 µg/L was observed.

Methylmalonic acidemia is an autosomal recessive metabolic disorder that disrupts normal amino acid metabolism. However, this kind of disease rarely demonstrates severe PH as the first clinical manifestation. Defective synthesis of the coenzymes adenosylcobalamin and methylcobalamin has been reported to be the main mediator of PH as a result of mitochondrial dysfunction[4]. These disorders might lead to capillary thrombosis in the lung, which would induce PH. In addition, a series of genome sequencing studies that focused on methylmalonic acidemia confirmed that the cobalamin C type was the most common type that would cause aggressive PH[5,6].

According to the European Society of Cardiology and American Heart Association guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pediatric PH[1,7], metabolic disorders have been listed in the 5th division. However, both of the guidelines only report glycogen storage disease, Gaucher disease and thyroid disorders. Although methylmalonic acidemia was failed to be mentioned, several studies also reported limited cases of methylmalonic acidemia inducing PH, which was first described by Iodice et al[8]. Beck et al[9] reviewed a cohort of 36 methylmalonic acidemia patients with cobalamin C defects and found that 7 of them presented PH.

Electrocardiogram, X-ray, echocardiography, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, pulmonary function test, and catheterization should always be performed as routinely recommended by guidelines. In this case, during the patient’s first stay in the hospital, we followed the recommended process for obtaining PH diagnosis. However, we failed to confirm the diagnosis quickly, which aggravated the patient’s condition. Then, during the second hospital stay, the combination of genome sequencing and metabolic disorder screening identified methylmalonic acidemia, cobalamin C type. After receiving targeted therapies, this patient’s impaired pulmonary artery pressure and heart function were reversed.

In summary, as metabolic disorders have already been mentioned in the guidelines, emerging types of metabolic dysfunction have been proven to have a manifestation of PH. It is recommended that genome sequencing and metabolic disorder screening are initially performed to obtain a diagnosis for unexplained or aggressive PH. Based on the literature review and our experience, once the patients presented with the abovementioned symptoms, genome sequencing and metabolic disorder screening should be prioritized rather than performed last to explore possible reasons. We summarized the criteria that indicate a need for these tests, as follows: (1) Failed to detect a structural malformation of the cardiovascular and pulmonary system; (2) Negative results for autoimmune disease; and (3) Aggressive pulmonary artery pressure elevation for a limited time or very early-onset PH without other disorders affecting other systems.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cheng TH, Yamaguchi K S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: MedE-Ma JY E-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Abman SH, Hansmann G, Archer SL, Ivy DD, Adatia I, Chung WK, Hanna BD, Rosenzweig EB, Raj JU, Cornfield D, Stenmark KR, Steinhorn R, Thébaud B, Fineman JR, Kuehne T, Feinstein JA, Friedberg MK, Earing M, Barst RJ, Keller RL, Kinsella JP, Mullen M, Deterding R, Kulik T, Mallory G, Humpl T, Wessel DL; American Heart Association Council on Cardiopulmonary, Critical Care, Perioperative and Resuscitation; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; and the American Thoracic Society. Pediatric Pulmonary Hypertension: Guidelines From the American Heart Association and American Thoracic Society. Circulation. 2015;132:2037-2099. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 586] [Cited by in RCA: 765] [Article Influence: 76.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tonelli AR, Arelli V, Minai OA, Newman J, Bair N, Heresi GA, Dweik RA. Causes and circumstances of death in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:365-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Barst RJ, McGoon MD, Elliott CG, Foreman AJ, Miller DP, Ivy DD. Survival in childhood pulmonary arterial hypertension: insights from the registry to evaluate early and long-term pulmonary arterial hypertension disease management. Circulation. 2012;125:113-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 276] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gündüz M, Ekici F, Özaydın E, Ceylaner S, Perez B. Reversible pulmonary arterial hypertension in cobalamin-dependent cobalamin C disease due to a novel mutation in the MMACHC gene. Eur J Pediatr. 2014;173:1707-1710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | De Simone L, Capirchio L, Roperto RM, Romagnani P, Sacchini M, Donati MA, de Martino M. Favorable course of previously undiagnosed Methylmalonic Aciduria with Homocystinuria (cblC type) presenting with pulmonary hypertension and aHUS in a young child: a case report. Ital J Pediatr. 2018;44:90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kido J, Mitsubuchi H, Sakanashi M, Matsubara J, Matsumoto S, Sakamoto R, Endo F, Nakamura K. Pulmonary artery hypertension in methylmalonic acidemia. Hemodial Int. 2017;21:E25-E29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Galiè N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, Gibbs S, Lang I, Torbicki A, Simonneau G, Peacock A, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Beghetti M, Ghofrani A, Gomez Sanchez MA, Hansmann G, Klepetko W, Lancellotti P, Matucci M, McDonagh T, Pierard LA, Trindade PT, Zompatori M, Hoeper M. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Respir J. 2015;46:903-975. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1826] [Cited by in RCA: 2153] [Article Influence: 215.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Iodice FG, Di Chiara L, Boenzi S, Aiello C, Monti L, Cogo P, Dionisi-Vici C. Cobalamin C defect presenting with isolated pulmonary hypertension. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e248-e251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Beck BB, van Spronsen F, Diepstra A, Berger RM, Kömhoff M. Renal thrombotic microangiopathy in patients with cblC defect: review of an under-recognized entity. Pediatr Nephrol. 2017;32:733-741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |