Published online Mar 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i6.1033

Peer-review started: December 19, 2019

First decision: January 12, 2020

Revised: March 11, 2020

Accepted: March 19, 2020

Article in press: March 19, 2020

Published online: March 26, 2020

Processing time: 97 Days and 18.1 Hours

Although cholecystectomy is the standard treatment modality, it has been shown that perioperative mortality is approaching 19% in critical and elderly patients. Percutaneous cholecystostomy (PC) can be considered as a safer option with a significantly lower complication rate in these patients.

To assess the clinical course of acute cholecystitis (AC) in patients we treated with PC.

The study included 82 patients with Grade I, II or III AC according to the Tokyo Guidelines 2018 (TG18) and treated with PC. The patients’ demographic and clinical features, laboratory parameters, and radiological findings were retrospectively obtained from their medical records.

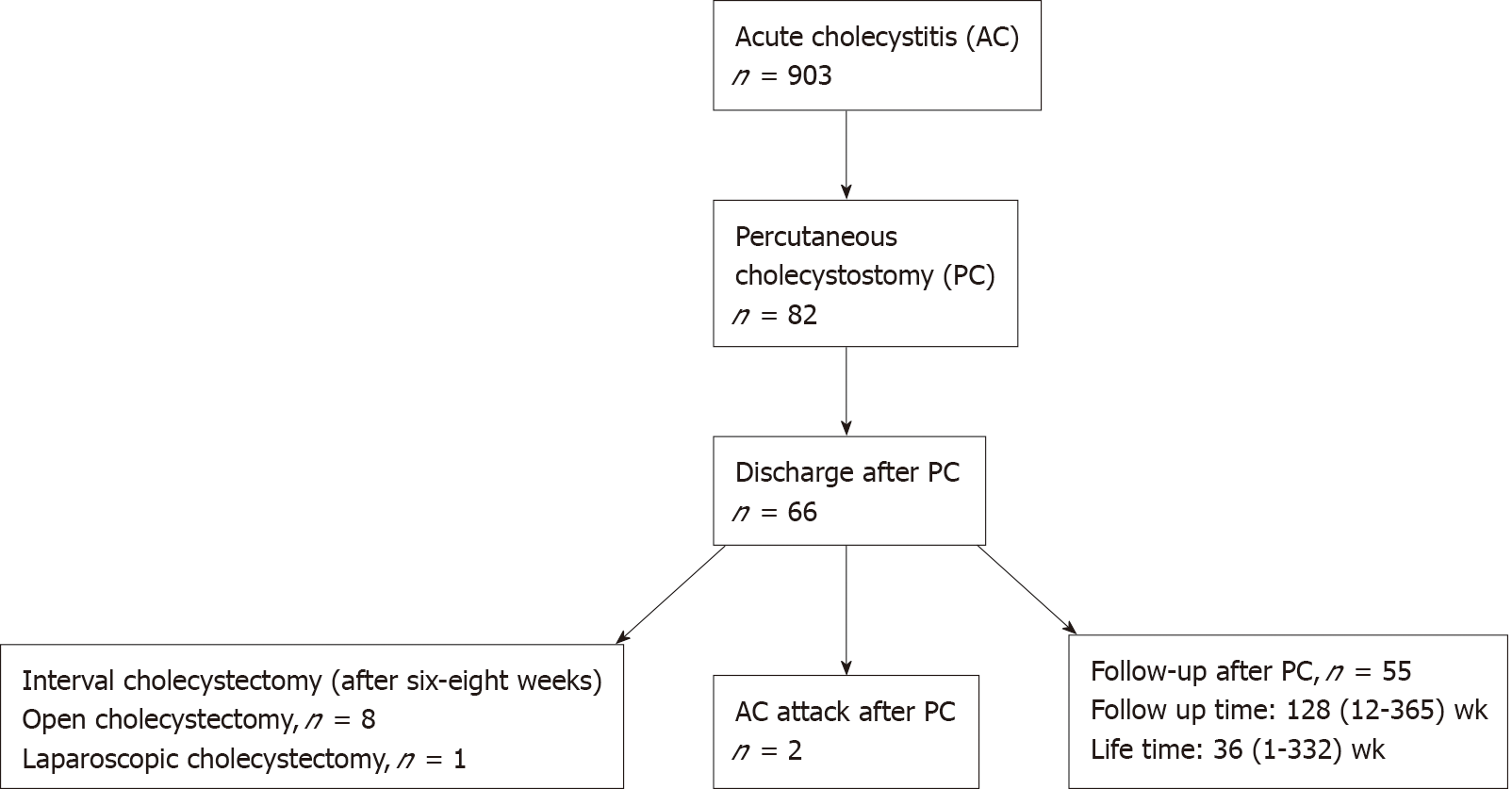

Eighty-two patients, 45 (54.9%) were male, and the median age was 76 (35-98) years. According to TG18, 25 patients (30.5%) had Grade I, 34 (41.5%) Grade II, and 23 (28%) Grade III AC. The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status score was III or more in 78 patients (95.1%). The patients, who had been treated with PC, were divided into two groups: discharged patients and those who died in hospital. The groups statistically significantly differed only concerning the ASA score (P = 0.0001) and WBCC (P = 0.025). Two months after discharge, two patients (3%) were readmitted with AC, and the intervention was repeated. Nine of the discharged patients (13.6%) underwent interval open cholecystectomy or laparoscopic cholecystectomy (8/1) within six to eight weeks after PC. The median follow-up time of these patients was 128 (12-365) wk, and their median lifetime was 36 (1-332) wk.

For high clinical success in AC treatment, PC is recommended for high-risk patients with moderate-severe AC according to TG18, elderly patients, and especially those with ASA scores of ≥ III. According to our results, PC, a safe, effective and minimally invasive treatment, should be preferred in cases suffering from AC with high risk of mortality associated with cholecystectomy.

Core tip: Percutaneous cholecystostomy is a safer treatment option especially for patients who have high risk of mortality after surgery. This option can be chosen after determining the severity of cholecystitis, the patient’s general status, and underlying disease. Tokyo Guidelines 2018 can be used to determine the severity of acute cholecystitis. In this study, we aimed to assess the clinical course of acute cholecystitis in patients treated with percutaneous cholecystostomy.

- Citation: Er S, Berkem H, Özden S, Birben B, Çetinkaya E, Tez M, Yüksel BC. Clinical course of percutaneous cholecystostomies: A cross-sectional study. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(6): 1033-1041

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i6/1033.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i6.1033

The treatment option for acute cholecystitis (AC) is open or laparoscopic cholecystectomy. However, percutaneous cholecystostomy (PC) is an alternative treatment in patients who have a high risk of mortality after surgery. PC is a technique that consists of percutaneous catheter placement in the gallbladder lumen under imaging guidance and has become an alternative to surgical cholecystectomy. PC is generally performed under local anesthesia by an interventional radiologist using the trans-hepatic or trans-peritoneal route[1]. This option can be chosen after determining the severity of cholecystitis, the patient’s general status, and underlying disease. Tokyo Guidelines 2018 (TG18) can be used to determine the severity of AC. According to TG18, particular care should be taken with patients who have Grade II and III AC in order to avoid biliary injury and reduce complications. Depending on the findings, the potential benefits of open cholecystectomy, subtotal cholecystectomy, and PC should be considered to decide on the best treatment[2]. In their 2017 guidelines, the World Society of Emergency Surgery recommended PC as a safe and effective treatment for AC in patients who are critically ill and/or have multiple comorbidities classified as grade 1B[3].

In 2010, the Society of Interventional Radiology recommended PC procedures for direct gallbladder access to either manage cholecystitis or remove gallstones, as well as a second-line means of biliary tract access to decompress the biliary tract, dilate biliary strictures, and place stents in malignant lesions[4]. In recent studies, PC has proven to be an effective treatment for 90% of patients with AC and the definitive treatment varies between 0%-54%[5-7]. Although laparoscopic cholecystectomy or open cholecystectomy is the standard treatment modality, it has been shown that perioperative mortality is approaching 19% in critical cases and elderly patients[8]. Therefore, PC can be considered as a safer option with a significantly lower complication rate[9]. The goal of this study was to assess the clinical course of patients with AC who had been treated with PC.

Between January 2010 and April 2017, 903 patients were hospitalized in our clinic with a diagnosis of AC This study included 82 of these patients who had been treated with PC. The patients’ medical records were retrospectively screened for the following data: Demographic characteristics, comorbidities, criteria for grading AC according to the TG18, mortality after PC or discharge, readmission, laboratory parameters, radiological findings, and the physical status scores of the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA). The cause of mortality was obtained from the national mortality notification system. The patients with coagulopathy or perforated gallbladder, and those without gallbladder stones were excluded from the study. The diagnosis of AC was confirmed with TG18, using clinical, laboratory and radiological findings. All grade I, II, and III patients were included. Oral feeding was stopped, and medical treatment with intravenous hydration and antibiotics (second-generation cephalosporin) was started for all patients.

PC was performed by a radiologist, who used a modified Seldinger technique on ultrasound and placed an 8-12F catheter in the gallbladder transhepatically. During the intervention, aspiration was performed initially, and then the gallbladder and bile ducts were visualized. After catheter placement, the position of the catheter was confirmed using a contrast agent. Ultrasound was performed by an interventional radiologist for the evaluation of catheter dislocation three to four days after the procedure. Cystic duct and distal common bile duct patency were evaluated by cholecystogram. If the cystic duct and the distal common bile duct had contrast passage and clinical improvement, the catheter was removed.

Oral feeding was stopped, and medical treatment with intravenous hydration and antibiotics (second-generation cephalosporin) was started for all patients. After PC, the following criteria were accepted as a satisfactory clinical response: Good general condition, no fever, and the white blood cell count decreased to the normal range. For these patients, the antibiotic treatment was terminated, and liquid feeding was started for those who did not have complaints of vomiting, lack of appetite, or distension.

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States) version 16.0 for Windows was used for the statistical analyses of the data. In addition to descriptive statistical methods (mean, standard deviation), the intergroup comparison of normally distributed parameters of the quantitative data was undertaken using Student’s t-test whereas the Mann-Whitney U-test was used for the parameters that were not normally distributed. Qualitative data was compared using the χ2 test, and a P level less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

There were 45 (54.9%) male and 37 (45.1%) female patients, with a median age of 76 (35-98) years. According to the TG18, there were 25 (30.5%), 34 (41.5%) and 23 (28%) patients with Grade I, II, and III AC, respectively. At admission, the patients’ mean C-reactive protein was 152.48 mg/L (SD ± 116.11) and white blood cell count was 15.306 μL (SD ± 7.97). The ASA score was ≥ III in 78 patients (95.1%) and < 3 in four (4.9%). After PC, mortality occurred in 16 patients (19.5%). The median scores of these patients according to the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) and ASA score were 3 and III, respectively (Table 1). After PC, the catheter removal time varied between four and thirteen (median: Seven) days. Only four patients complained about abdominal pain. However, physical examination, ultrasound, or laboratory parameters did not show any abnormality. There were no major complications due to PC. One patient had bleeding into the gallbladder during the procedure, but there was no problem during the follow-up.

| Patient | Feature |

| Age-median (minimum-maximum) | 76 (35-98) |

| Sex-Male/Female | 45 (54.9%)/37 (45.1%) |

| CRP/WBCC, mean ± SD | 152.48 ± 116.11 mg/L/15.306 ± 7.970 μL |

| Acute Cholecystitis Grades1 | |

| Grade I | 25 (30.5%) |

| Grade II | 34 (41.5%) |

| Grade III | 23 (28%) |

| ASA Score | |

| ≥ III | 78 (95.1%) |

| < III | 4 (4.9%) |

| Operation type | |

| Open cholecystectomy | 8 (9.75%) |

| Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | 1 (1.2%) |

| No operation | 73 (89.1%) |

| Catheter removal time (d)-median (minimum-maximum) | 7 (4-13) |

| Mortality at hospital after PC, n (%) | 16 (19.5%) |

| Acute Cholecystitis attack after PC, n (%) | 2 (3%) |

| After PC | |

| Follow-up time (wk)- median (minimum-maximum) | 128 (12-365) |

| Lifetime (wk) - median (minimum-maximum) | 36 (1-332) |

Sixty-six (80.5%) patients were well enough to be discharged after PC. Of these patients, 62 (94%) had CCI and ASA scores of 2 and ≥ III, respectively, and four (6%) patients had an ASA score of < III. Two months after discharge, two patients (3%) were readmitted with AC and the intervention was repeated. Nine of the discharged patients (13.6%) underwent interval open cholecystectomy or laparoscopic cholecystectomy (8/1) within six to eight weeks after PC. The reason for performing interval cholecystectomy in these patients was because they had a good overall condition and less comorbidities.

Sixty-six patients (80.4%) were followed up without operation. The median follow-up time of these patients was 128 (12-365) wk and their median lifetime was 36 (1-332) wk. Thirty-seven (56%) patients died of non-biliary causes during the follow-up period, and these patients’ median CCI score was 3 (Table 1). The patients that survived had a median CCI of 2, but there was no statistical difference between the two groups.

The patients who had been treated with PC were divided into two groups: Those who died in hospital and those who were discharged. The two groups were compared in terms of CCI and ASA scores, age, and white blood cell count at a cut-off value of 18000 μL. There were statistically significant differences in ASA score (P = 0.0001) and white blood cell count (P = 0.025) between the groups. In this study, all the 66 patients (100%) with an ASA score of < III were discharged from the hospital and all the 16 patients (100%) with an ASA score of ≥ III died in hospital. The mean white blood cell count was 14400 μL in deceased patients and 10.500 μL in discharged patients. The remaining parameters did not show any statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) (Table 2). The flowchart of the patients who had been treated with PC are schematized in Figure 1.

| Died in hospital, n (%) | Discharged, n (%) | P value | |||

| CCI | ≥ 2 | 9 (26.4%) | 25 (73.5%) | 0.2583 | |

| < 2 | 7 (14.5%) | 41 (85.4%) | |||

| ASA | ≥ III | 16 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0.0001 | |

| < III | 0 (0%) | 66 (100%) | |||

| WBCC | Median (IQR) | 14400 (10000-19800) | 10500 (7900-15300) | 0.025 | |

| Age | Median (minimum-maximum) | 76 (67-82) | 80 (65-85.5) | 0.695 | |

Gallstone disease is a common condition with estimated prevalence of 10%-20%, increasing to 15%-24% in patients aged over 70 years[10]. In another study, it was reported that female gender was a risk factor for cholesterol gallstones[11]. Therefore, the incidence of AC also increases with age. Despite the availability of many studies in the literature concerning the treatment of AC, there is no consensus about the treatment of older patients and those at a higher risk[12]. Although the gold standard treatment for AC is laparoscopic cholecystectomy, PC presents as a good option for the elderly patients and those with comorbidities and grade II or III AC (TG18).

In this study, the median catheter removal time was seven days after the procedure. The catheter removal time was determined based on the consensus of a radiologist and a clinician who took into consideration the patients’ clinical condition and response to the treatment. In the literature, some authors suggested four to six weeks before the removal of catheter to prevent recurrence, but many recent studies recommend deciding on the removal time with a control ultrasound or cholangiography after eight to twelve days of intervention[6,13].

In the literature, there are varying and conflicting views and approaches concerning the time of removal of the catheter[14]. For example, in their review, Macchini et al[14] reported that they left the catheter in place for a median of nine (2-28) d. In the current study, since the PC procedure was performed with a transhepatic approach, the general condition of the patients was better and the laboratory results were improved, and the ultrasound performed by the interventional radiologist ruled out complications related to the catheter. In this study, the catheter was removed after a median of seven (4-13) d.

Many studies describe that PC successfully relieves the acute phase symptoms of AC in up to 85% of patients[8,12,15]. Alvino et al[16] concluded that the symptoms of AC had been relieved in 91% of patients after PC. Their research was based on the largest group of patients ever studied. In the same study, the authors reported the rate of interval cholecystectomy as 38% but also pointed out that their sample was younger and had low ASA and CCI scores. The rate of interval cholecystectomy after PC was reported as 23%-57% in different studies[13,17-19]. Yeo et al[7] reported a 41% eventual cholecystectomy rate in a cohort with a median age similar to our study. However, in the current study, there were only nine patients (13.6%) who were fit for interval cholecystectomy. This may due to our patients’ higher comorbidity rate, older age, and unwillingness for surgery. Additionally, compared to the literature (15%-42%)[13,18-20] we had a higher mortality rate (56%) in the follow-up period due to non-biliary causes, which may also explain the low cholecystectomy rate. In patients with grade II or III AC, a CCI of ≥ 4 and an ASA score of ≥ III, TG18 recommends conservative treatment with PC when necessary[2]. This is consistent with our treatment approach that indicates PC for only patients who have high risk of mortality after surgery. Except this, in our study, 25 (30.5%) patients had mild AC but underwent PC due to comorbidities. This may show the significance of comorbidities in selecting the treatment options. In their study cited in TG18, Amirthalingam et al[21] stated that not only severity grading but also patient comorbidity affect the clinical decision for these patients.

PC is also considered as an alternative treatment method for patients who are not suitable for laparoscopic cholecystectomy at hospital admission. However, in our study, only one patient underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy[7]. This may be due to the worse comorbidity profiles of our patients or technical issues that could not be eliminated due to the retrospective nature of the study, such as the surgeon’s experience or patient history of laparotomy.

In the literature, many authors consider PC as a definitive treatment option due to low rates of AC attacks or readmissions with AC[6,13,22,23]. In their study, Winbladh et al[8] indicated that PC provided 85.6% successful treatment in AC. However, in another study, the role of PC in the definitive treatment of high-risk patients with AC was considered controversial[24]. Some studies claim that in 25% of AC cases presenting with a stone, recurrent cholecystitis attacks occur two to three months after PC[8,20,25-29]. In our study, only two patients (3%) who had undergone PC were readmitted with an AC attack. Therefore, our results support the hypothesis that PC is the most accurate treatment option for patients with high risk of mortality after urgent surgery. High-risk patients can be described as having at least one of the following criteria: Grade II or III AC, ASA score ≥ III, and /or CCI score > 2. Similar to our study, Solaini et al[13] suggested PC as the definitive treatment in highly-selected cases for which the risk of death for non-biliary causes might be higher than that of recurrence.

TG18 uses the white blood cell count cut-off value of 18000 μL for defining moderate and severe AC[2]. In our study, the group of patients who died in hospital had a statistically higher white blood cell count, but when the groups were compared based on this cut-off value, there was no statistically significant difference between the patients that were discharged and those that died. This indicates that this cut-off value may need to be lowered for more accurate grading.

In the presented study, there were statistically significant differences between the groups when the ASA score was considered. All patients with an ASA of ≥ III died in hospital and those with an ASA of < III were fit for discharge. This suggests that in the selected patient group, ASA scores were associated with mortality even if the patients did not have surgery and only underwent PC. Similarly, Yeo et al[7] and Cha et al[30] showed a positive correlation between ASA score and mortality after PC.

In a multicenter study comparing laparoscopic cholecystectomy and PC in high-risk patients with AC, the latter was found to be more effective in reducing morbidity, necessity of intensive care and hospital stay[31]. In their study conducted with 8818 elderly patients with grade III AC, Dimou et al[32] showed that the probability of requiring cholecystectomy was low at any time during a two-year follow-up after PC.

Various mortality rates after PC have been reported in the literature. Small retrospective studies have reported these rates to be 4%-17% in hospital and as high as 7%-26% within the first 30 d after surgery[33,34]. In our study, the mortality rate at hospital was 16% and mortality was mostly seen in patients with CCI and ASA scores of 3 and III, respectively. This rate is compatible with the reports in the literature. Concerning CCI and ASA score, we can say that both evaluate the general condition of the patients.

Studies in the literature have different median follow-up durations, ranging from 38 mo to 14 years[35-37]. Cooper et al[35] reported the mean mortality rate as 43% on the 387th d (27-1260) of follow-up after PC. Noh et al[36] showed that 86 patients (97.7%) had been successfully followed up for 1227 d after PC without an AC attack. Similarly, Schmidt et al[37] reported that if patients remained asymptomatic after a successful PC, there would be no need for elective surgery after five years of follow-up. In the current study, 66 patients discharged after PC were followed up for a median of 128 wk, and their median lifetime was only 36 wk. Of these patients, 37 (56%) died of non-biliary causes and only two (3%) had AC attacks. This high rate of mortality can be explained by older age, poor general condition, worse comorbidity profiles, and high ASA scores of the patients. Furthermore, these results show the effectiveness, importance and sufficiency of PC in high-risk patients with low life expectancy.

The most important limitation of this study was the bias concerning standardized patient selection.

Further randomized trials are needed to confirm our results prospectively.

In the light of our results, for high clinical success, we recommend PC for high-risk patients with moderate-severe AC according to TG18, elderly patients, and especially those with an ASA score of ≥ III. However, this recommendation should be supported with prospective randomized trials. PC, a safe, effective and minimally invasive treatment, should be preferred in patients suffering from AC with high risk of mortality associated with cholecystectomy.

In this retrospective study, the clinical course of percutaneous cholecystostomy (PC) was evaluated in 82 patients who had comorbidities and had high mortality risk after surgery. The benefits and success rate of PC were revealed in the selected patient population.

In the literature, the significance of PC was not identified in patients who had Grade 2 and 3 acute cholecystitis (AC) (Tokyo Guidelines 2018) and comorbidities. This study confirms that PC is a safe and adequate treatment option.

In this study, we emphasized that PC alone is an adequate treatment in patients with AC based on our finding that only nine of the 66 patients discharged from the hospital required cholecystectomy. In patients that died, mortality usually occurred for non-biliary reasons during the follow-up without recurrent episodes. PC without general anesthesia may be an adequate treatment option in these patients.

The study was planned retrospectively. In the follow-up of patients undergoing PC, the causes of death and duration of survival after the procedure were obtained from the electronic medical records.

Our findings support that PC is an effective alternative method that can be safely applied to patients with a high comorbidity load, and it can regress clinical symptoms in this patient group. During the retrospective acquisition of the study data by screening the electronic medical records, the number of patients was reduced due to the exclusion of those with incomplete records. Therefore, a future prospective study can be planned to obtain the records of all patients in detail to further emphasize the individual adequacy of PC.

Except for nine cases, PC alone was an adequate and safe treatment alternative in all the remaining evaluated patients with AC. PC is an alternative effective treatment option in AC cases with a high comorbidity load. This study revealed that in the long-term follow-up of patients who had undergone PC and had been discharged, mortality occurred mostly due to non-biliary causes, except for a limited number of cases with a history of episodes, confirming that the procedure was successful, which is a finding that contributes to the literature. PC can be safely used as an alternative treatment in patients with high risk of surgery and provides adequate clinical improvement. We consider that PC presents as a good alternative with a high success rate in patients with AC who have a comorbidity load, those at high risk of anesthesia-related complications, and those that do not agree to undergo surgery after clinical recovery is achieved.

Despite performing PC in the patient population with AC and high comorbidity, approximately 20% of the patients developed mortality. However, the considerable success rate of the procedure presents it as a good treatment option.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: Turkey

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Aoki T, Boukerrouche A, Kumar A S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: A E-Editor: Li X

| 1. | Little MW, Briggs JH, Tapping CR, Bratby MJ, Anthony S, Phillips-Hughes J, Uberoi R. Percutaneous cholecystostomy: the radiologist's role in treating acute cholecystitis. Clin Radiol. 2013;68:654-660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Okamoto K, Suzuki K, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Asbun HJ, Endo I, Iwashita Y, Hibi T, Pitt HA, Umezawa A, Asai K, Han HS, Hwang TL, Mori Y, Yoon YS, Huang WS, Belli G, Dervenis C, Yokoe M, Kiriyama S, Itoi T, Jagannath P, Garden OJ, Miura F, Nakamura M, Horiguchi A, Wakabayashi G, Cherqui D, de Santibañes E, Shikata S, Noguchi Y, Ukai T, Higuchi R, Wada K, Honda G, Supe AN, Yoshida M, Mayumi T, Gouma DJ, Deziel DJ, Liau KH, Chen MF, Shibao K, Liu KH, Su CH, Chan ACW, Yoon DS, Choi IS, Jonas E, Chen XP, Fan ST, Ker CG, Giménez ME, Kitano S, Inomata M, Hirata K, Inui K, Sumiyama Y, Yamamoto M. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: flowchart for the management of acute cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018;25:55-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 556] [Cited by in RCA: 498] [Article Influence: 71.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sartelli M, Chichom-Mefire A, Labricciosa FM, Hardcastle T, Abu-Zidan FM, Adesunkanmi AK, Ansaloni L, Bala M, Balogh ZJ, Beltrán MA, Ben-Ishay O, Biffl WL, Birindelli A, Cainzos MA, Catalini G, Ceresoli M, Che Jusoh A, Chiara O, Coccolini F, Coimbra R, Cortese F, Demetrashvili Z, Di Saverio S, Diaz JJ, Egiev VN, Ferrada P, Fraga GP, Ghnnam WM, Lee JG, Gomes CA, Hecker A, Herzog T, Kim JI, Inaba K, Isik A, Karamarkovic A, Kashuk J, Khokha V, Kirkpatrick AW, Kluger Y, Koike K, Kong VY, Leppaniemi A, Machain GM, Maier RV, Marwah S, McFarlane ME, Montori G, Moore EE, Negoi I, Olaoye I, Omari AH, Ordonez CA, Pereira BM, Pereira Júnior GA, Pupelis G, Reis T, Sakakhushev B, Sato N, Segovia Lohse HA, Shelat VG, Søreide K, Uhl W, Ulrych J, Van Goor H, Velmahos GC, Yuan KC, Wani I, Weber DG, Zachariah SK, Catena F. The management of intra-abdominal infections from a global perspective: 2017 WSES guidelines for management of intra-abdominal infections. World J Emerg Surg. 2017;12:29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 282] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 31.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Saad WE, Wallace MJ, Wojak JC, Kundu S, Cardella JF. Quality improvement guidelines for percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography, biliary drainage, and percutaneous cholecystostomy. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010;21:789-795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Baron TH, Grimm IS, Swanstrom LL. Interventional Approaches to Gallbladder Disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:357-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kirkegård J, Horn T, Christensen SD, Larsen LP, Knudsen AR, Mortensen FV. Percutaneous cholecystostomy is an effective definitive treatment option for acute acalculous cholecystitis. Scand J Surg. 2015;104:238-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yeo CS, Tay VW, Low JK, Woon WW, Punamiya SJ, Shelat VG. Outcomes of percutaneous cholecystostomy and predictors of eventual cholecystectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2016;23:65-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Winbladh A, Gullstrand P, Svanvik J, Sandström P. Systematic review of cholecystostomy as a treatment option in acute cholecystitis. HPB (Oxford). 2009;11:183-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 222] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Li M, Li N, Ji W, Quan Z, Wan X, Wu X, Li J. Percutaneous cholecystostomy is a definitive treatment for acute cholecystitis in elderly high-risk patients. Am Surg. 2013;79:524-527. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Duncan CB, Riall TS. Evidence-based current surgical practice: calculous gallbladder disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:2011-2025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kim JW, Oh HC, Do JH, Choi YS, Lee SE. Has the prevalence of cholesterol gallstones increased in Korea? A preliminary single-center experience. J Dig Dis. 2013;14:559-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Melloul E, Denys A, Demartines N, Calmes JM, Schäfer M. Percutaneous drainage versus emergency cholecystectomy for the treatment of acute cholecystitis in critically ill patients: does it matter? World J Surg. 2011;35:826-833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Solaini L, Paro B, Marcianò P, Pennacchio GV, Farfaglia R. Can percutaneous cholecystostomy be a definitive treatment in the elderly? Surg Pract. 2016;20:144-148. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Macchini D, Degrate L, Oldani M, Leni D, Padalino P, Romano F, Gianotti L. Timing of percutaneous cholecystostomy tube removal: systematic review. Minerva Chir. 2016;71:415-426. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Macrì A, Scuderi G, Saladino E, Trimarchi G, Terranova M, Versaci A, Famulari C. Acute gallstone cholecystitis in the elderly: treatment with emergency ultrasonographic percutaneous cholecystostomy and interval laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:88-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Alvino DML, Fong ZV, McCarthy CJ, Velmahos G, Lillemoe KD, Mueller PR, Fagenholz PJ. Long-Term Outcomes Following Percutaneous Cholecystostomy Tube Placement for Treatment of Acute Calculous Cholecystitis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;21:761-769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Anderson JE, Chang DC, Talamini MA. A nationwide examination of outcomes of percutaneous cholecystostomy compared with cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis, 1998-2010. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:3406-3411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Khasawneh MA, Shamp A, Heller S, Zielinski MD, Jenkins DH, Osborn JB, Morris DS. Successful laparoscopic cholecystectomy after percutaneous cholecystostomy tube placement. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78:100-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | de Mestral C, Gomez D, Haas B, Zagorski B, Rotstein OD, Nathens AB. Cholecystostomy: a bridge to hospital discharge but not delayed cholecystectomy. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74:175-179; discussion 179-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | McKay A, Abulfaraj M, Lipschitz J. Short- and long-term outcomes following percutaneous cholecystostomy for acute cholecystitis in high-risk patients. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:1343-1351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Amirthalingam V, Low JK, Woon W, Shelat V. Tokyo Guidelines 2013 may be too restrictive and patients with moderate and severe acute cholecystitis can be managed by early cholecystectomy too. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:2892-2900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Eggermont AM, Laméris JS, Jeekel J. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous transhepatic cholecystostomy for acute acalculous cholecystitis. Arch Surg. 1985;120:1354-1356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Shirai Y, Tsukada K, Kawaguchi H, Ohtani T, Muto T, Hatakeyama K. Percutaneous transhepatic cholecystostomy for acute acalculous cholecystitis. Br J Surg. 1993;80:1440-1442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | La Greca A, Di Grezia M, Magalini S, Di Giorgio A, Lodoli C, Di Flumeri G, Cozza V, Pepe G, Foco M, Bossola M, Gui D. Comparison of cholecystectomy and percutaneous cholecystostomy in acute cholecystitis: results of a retrospective study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2017;21:4668-4674. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Chang YR, Ahn YJ, Jang JY, Kang MJ, Kwon W, Jung WH, Kim SW. Percutaneous cholecystostomy for acute cholecystitis in patients with high comorbidity and re-evaluation of treatment efficacy. Surgery. 2014;155:615-622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Granlund A, Karlson BM, Elvin A, Rasmussen I. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous cholecystostomy in high-risk surgical patients. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2001;386:212-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Jang WS, Lim JU, Joo KR, Cha JM, Shin HP, Joo SH. Outcome of conservative percutaneous cholecystostomy in high-risk patients with acute cholecystitis and risk factors leading to surgery. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:2359-2364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Morse BC, Smith JB, Lawdahl RB, Roettger RH. Management of acute cholecystitis in critically ill patients: contemporary role for cholecystostomy and subsequent cholecystectomy. Am Surg. 2010;76:708-712. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Skillings JC, Kumai C, Hinshaw JR. Cholecystostomy: a place in modern biliary surgery? Am J Surg. 1980;139:865-869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Cha BH, Song HH, Kim YN, Jeon WJ, Lee SJ, Kim JD, Lee HH, Lee BS, Lee SH. Percutaneous cholecystostomy is appropriate as definitive treatment for acute cholecystitis in critically ill patients: a single center, cross-sectional study. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2014;63:32-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Simorov A, Ranade A, Parcells J, Shaligram A, Shostrom V, Boilesen E, Goede M, Oleynikov D. Emergent cholecystostomy is superior to open cholecystectomy in extremely ill patients with acalculous cholecystitis: a large multicenter outcome study. Am J Surg. 2013;206:935-940; discussion 940-941. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Dimou FM, Adhikari D, Mehta HB, Riall TS. Outcomes in Older Patients with Grade III Cholecystitis and Cholecystostomy Tube Placement: A Propensity Score Analysis. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;224:502-511.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Joseph T, Unver K, Hwang GL, Rosenberg J, Sze DY, Hashimi S, Kothary N, Louie JD, Kuo WT, Hofmann LV, Hovsepian DM. Percutaneous cholecystostomy for acute cholecystitis: ten-year experience. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012;23:83-8.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Paran H, Zissin R, Rosenberg E, Griton I, Kots E, Gutman M. Prospective evaluation of patients with acute cholecystitis treated with percutaneous cholecystostomy and interval laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Int J Surg. 2006;4:101-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Cooper S, Donovan M, Grieve DA. Outcomes of percutaneous cholecystostomy and predictors of subsequent cholecystectomy. ANZ J Surg. 2018;88:E598-E601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Noh SY, Gwon DI, Ko GY, Yoon HK, Sung KB. Role of percutaneous cholecystostomy for acute acalculous cholecystitis: clinical outcomes of 271 patients. Eur Radiol. 2018;28:1449-1455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Schmidt M, Søndenaa K, Vetrhus M, Berhane T, Eide GE. Long-term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of observation versus surgery for acute cholecystitis: non-operative management is an option in some patients. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:1257-1262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |