Published online Feb 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i4.670

Peer-review started: December 3, 2019

First decision: December 23, 2019

Revised: February 4, 2020

Accepted: February 12, 2020

Article in press: February 12, 2020

Published online: February 26, 2020

Processing time: 85 Days and 7.3 Hours

Sepsis is fatal in patients with gastrointestinal perforation (GIP). However, few studies have focused on this issue.

To investigate the risk factors for postoperative sepsis in patients with GIP.

This was a retrospective study performed at the Department of General Surgery in our treatment center. From January 2016 to December 2018, the medical records of patients with GIP who underwent emergency surgery were reviewed. Patients younger than 17 years or who did not undergo surgical treatment were excluded. The patients were divided into the postoperative sepsis group and the non-postoperative sepsis group. Clinical data for both groups were collected and compared, and the risk factors for postoperative sepsis were investigated. The institutional ethical committee of our hospital approved the study.

Two hundred twenty-six patients were admitted to our department with GIP. Fourteen patients were excluded: Four were under 17 years old, and 10 did not undergo emergency surgery due to high surgical risk and/or disagreement with the patients and their family members. Two hundred twelve patients were finally enrolled in the study; 161 were men, and 51 were women. The average age was 62.98 ± 15.65 years. Postoperative sepsis occurred in 48 cases. The prevalence of postoperative sepsis was 22.6% [95% confidence interval (CI): 17.0%-28.3%]. Twenty-eight patients (13.21%) died after emergency surgery. Multiple logistic regression analysis confirmed that the time interval from abdominal pain to emergency surgery [odds ratio (OR) = 1.021, 95%CI: 1.005-1.038, P = 0.006], colonic perforation (OR = 2.761, CI: 1.821–14.776, P = 0.007), perforation diameter (OR = 1.062, 95%CI: 1.007-1.121, P = 0.027), and incidence of malignant tumor-related perforation (OR = 5.384, 95%CI: 1.762-32.844, P = 0.021) were associated with postoperative sepsis.

The time interval from abdominal pain to surgery, colonic perforation, diameter of perforation, and the incidence of malignant tumor-related perforation were risk factors for postoperative sepsis in patients with GIP.

Core tip: Postoperative sepsis is fatal in patients with gastrointestinal perforation (GIP). The definition of sepsis was revised in 2016. Few studies have focused on the risk factors for postoperative sepsis (revision 2016). In this study, the medical records of patients with GIP who underwent emergency surgery from January 2016 to December 2018 were reviewed. It was found that the time interval from abdominal pain to emergency surgery, colonic perforation, diameter of perforation, and the incidence of malignant tumor-related perforation were risk factors for postoperative sepsis in patients with GIP.

- Citation: Xu X, Dong HC, Yao Z, Zhao YZ. Risk factors for postoperative sepsis in patients with gastrointestinal perforation. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(4): 670-678

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i4/670.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i4.670

Gastrointestinal perforation (GIP) is a common acute abdominal injury. It usually requires active rescue in the intensive care unit with an emergency laparotomy[1]. The risk factors for GIP vary and include older age, diabetes, antecedent diverticulitis, glucocorticoid therapy, and use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs[2-4]. GIP is an indication for emergency surgery. Laparotomy and laparoscopic surgery are the most effective and important treatment methods[5,6] despite reports regarding therapeutic endoscopy and conservative treatment for GIP[7-9].

Previous studies have shown that GIP is the most common cause of sepsis in the intensive care unit[10,11]. Wickel et al[12] reported that the incidence of postoperative sepsis was > 70% in patients with GIP, thus leading to severe peritonitis. Despite advances in intensive care and antibiotic treatment, the hospital mortality rate due to abdominal sepsis remains high, and the mortality due to a postoperative septic abdomen in patients with GIP can reach 50%[12-16]. The definition of sepsis was revised in 2016 (sepsis 3.0) to better reflect the prognosis and organ function damage rather than being defined as infection-induced systemic inflammatory response syndrome[17]. Once sepsis occurs, the prognosis worsens, and few studies have focused on the risk factors for postoperative sepsis in patients with GIP. The present study was conducted to investigate these risk factors.

This was a retrospective study performed at the Department of General Surgery in our treatment center. From January 2016 to December 2018, the medical records of patients with GIP who underwent emergency surgery were reviewed. Patients younger than 17 years or who did not undergo surgical treatment were excluded. Patients were divided into the postoperative sepsis group and the non-postoperative sepsis group. Clinical data for both groups were collected and compared, and the risk factors for postoperative sepsis were investigated. The institutional ethical committee of our hospital approved the study (No. 2019110). All study participants provided informed written consent during treatment. The statistical methods used in this study were reviewed by Doctor Ren from Henan University.

Following admission, each patient underwent routine blood and biochemical tests. A computed tomography scan was also performed for a detailed diagnosis. After GIP was diagnosed, emergency surgery (either laparotomy or laparoscopic surgery) was performed. All patients received third-generation cephalosporins to treat the infection after admission. Data for each patient, including demographic characteristics (e.g., age, sex, and body mass index), laboratory examination results at admission, perforation location, etiology (i.e., trauma, malignant tumor, or benign ulcer), time interval from abdominal pain to surgery, perforation diameter, surgical procedure, and whether postoperative sepsis occurred were collected. In the present study, sepsis was defined as life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection. For clinical operationalization, organ dysfunction was represented by an increase of ≥ 2 points on the Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment score[17]. Sepsis was evaluated daily after surgery, until the patients were discharged.

All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS, version 20.0 for Windows (IBM, Analytics, Armonk, NY, United States). A Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was performed to determine whether continuous variables conformed to a normal distribution, and then the Student’s t-test (for normally distributed data) or the Mann-Whitney U test (for data that were not normally distributed) were performed. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables. Multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the risk factors for GIP. Odds ratios (ORs) are expressed with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Kaplan-Meier estimates followed by a log-rank test were used to evaluate the prognoses between different groups. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Two hundred twenty-six patients were admitted to our department due to GIP. Fourteen patients were excluded: Four were under 17 years old, and 10 did not undergo emergency surgery because of high surgical risk and/or disagreement with the patients and their family members. Two hundred twelve patients were finally enrolled in the study; 161 were men, and 51 were women. The average age was 62.98 ± 15.65 years. Postoperative sepsis occurred in 48 cases. The prevalence of postoperative sepsis was 22.6% (95%CI: 17.0%-28.3%). Twenty-eight patients (13.21%) died after emergency surgery. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the 212 patients.

| Clinical variables | Enrolled patients (n = 212) | Univariate analysis | ||

| Postoperative sepsis group (n = 48) | Non-postoperative sepsis group (n = 164) | P value | ||

| Age, (yr; mean ± SD) | 62.98 ± 15.65 | 72.58 ± 14.89 | 60.17 ± 14.77 | < 0.001 |

| Female, n (%) | 51 (24.06) | 16 (33.33) | 35 (21.34) | 0.123 |

| BMI (kg/m2; mean ± SD) | 22.40 ± 2.95 | 22.10 ± 2.67 | 22.48 ± 3.02 | 0.441 |

| Temperature [°C, mean (IQR)] | 36.75 (36.50-37.00) | 36.80 (36.63-38.80) | 36.65 (36.50-37.00) | 0.001 |

| Heart rate [beats/min, mean (IQR)] | 80 (77-88) | 87 (80-99) | 80 (78-84) | < 0.001 |

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg; mean ± SD) | 90.75 ± 13.80 | 84.97 ± 12.11 | 92.45 ± 13.84 | 0.001 |

| Breathing rate [times/min, mean (IQR)] | 20 (19-21) | 20 (20-22) | 20 (10-21) | 0.12 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L, mean ± SD) | 135.33 ± 19.85 | 130.73 ± 19.32 | 136.67 ± 19.86 | 0.068 |

| Serum creatinine (μmol/L, mean ± SD) | 84.38 ± 49.89 | 106.38 ± 79.37 | 77.94 ± 40.12 | < 0.001 |

| Total bilirubin (μmol/L, mean ± SD) | 15.99 ± 12.36 | 13.75 ± 6.48 | 16.65 ± 13.56 | 0.152 |

| White blood cells (× 109/L) [mean (IQR)] | 10.74 (7.20-15.00) | 7.50 (4.48-13.21) | 11.42 (7.83-15.20) | 0.003 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L, mean ± SD) | 128.67 ± 77.42 | 157.08 ± 77.26 | 120.35 ± 75.70 | 0.004 |

| Preoperative ASA score [mean (IQR)] | 2 (1-3) | 3 (2-4) | 2 (1-2) | < 0.001 |

| Ascites, n (%) | 156 (73.58) | 48 (100) | 108 (65.85) | < 0.001 |

| Diameter of perforation, (mm, mean ± SD) | 12.69 ± 10.63 | 15.93 ± 10.11 | 11.75 ± 10.61 | 0.015 |

| Time interval from abdominal pain to emergency surgery (h, mean ± SD) | 23.49 ± 35.63 | 42.21 ± 44.62 | 18.01 ± 30.59 | 0.001 |

| Operation duration, [h, mean (IQR)] | 2 (1.5-2.5) | 2 (15-3) | 2 (1.3-2) | 0.061 |

| Anatomy of GIP, n (%) | ||||

| Stomach | 118 (55.66) | 12 (25) | 106 (64.63) | 0.001 |

| Duodenum | 33 (15.57) | 10 (20.83) | 23 (14.02) | 0.262 |

| Jejunum/Ileum | 19 (8.96) | 6 (12.5) | 13 (7.93) | 0.388 |

| Colon | 42 (19.81) | 16 (33.33) | 26 (20.12) | 0.008 |

| Etiology, n (%) | ||||

| Trauma | 80 (37.74) | 18 (37.5) | 62 (37.80) | 1.000 |

| Malignant tumor | 30 (14.15) | 14 (29.17) | 16 (9.76) | 0.002 |

| Benign ulcer | 102 (48.11) | 16 (33.33) | 86 (52.44) | 0.220 |

| Surgical procedure, n (%) | ||||

| Repair | 169 (79.71) | 30 (62.5) | 139 (84.76) | 0.002 |

| Repair + Ostomy1 | 11 (5.19) | 3 (6.25) | 8 (4.88) | 0.751 |

| Resection and anastomosis2 | 6 (2.83) | 2 (4.17) | 4 (2.44) | 0.623 |

| Resection + ostomy3 | 12 (5.66) | 4 (8.33) | 8 (4.88) | 0.451 |

| Digestive tract reconstruction4 | 14 (6.60) | 9 (18.75) | 5 (3.05) | 0.001 |

| Laparoscopic surgery, n (%) | 71 (33.50) | 19 (39.58) | 52 (31.71) | 0.385 |

| Co-morbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 33 (15.57) | 6 (12.5) | 27 (16.46) | 0.652 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 19 (8.96) | 7 (14.58) | 12 (7.32) | 0.149 |

| Coronary disease | 27 (12.74) | 6 (12.5) | 21 (12.81) | 1.000 |

| Sepsis, n (%) | 48 (23.11) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Table 2 shows the emergency surgical procedures. Of the 212 enrolled patients, 169 underwent perforation repair: Seventy one of those underwent laparoscopic gastrointestinal repair, and 98 underwent standard surgical repair. Of the remaining 43 patients, 11 underwent repair + ostomy (colonic repair + enterostomy), 6 underwent resection and anastomosis, 12 underwent resection + ostomy, and 14 underwent subtotal gastrectomy + gastrojejunostomy due to gastric malignant perforation.

| Emergency surgical procedure | Location of the perforation | n (%) |

| Laparoscopic surgery | ||

| Laparoscopic gastric repair | Stomach1 | 52 (24.52) |

| Laparoscopic duodenal repair | Duodenum | 10 (4.72) |

| Laparoscopic jejunal/ileal repair | Jejunum/Ileum | 9 (4.25) |

| Open abdominal surgery | ||

| Repair | ||

| Gastric repair | Stomach1 | 48 (22.64) |

| Duodenal repair | Duodenum | 23 (10.85) |

| Jejunal/ileal repair | Jejunum/Ileum | 8 (3.77) |

| Colonic repair | Colon2 | 19 (8.96) |

| Repair + ostomy | ||

| Colonic repair + enterostomy | Colon2 | 11 (5.019) |

| Resection and anastomosis | ||

| Partial gastrectomy | Stomach3 | 4 (1.87) |

| Jejunal/ileal resection and anastomosis | Jejunum/Ileum | 2(0.94) |

| Resection + ostomy | ||

| Partial colectomy + colostomy | Colon4 | 9 (4.24) |

| Partial colectomy and anastomosis + enterostomy | Colon4 | 3 (1.42) |

| Digestive tract reconstruction | ||

| Subtotal gastrectomy + gastrojejunostomy | Stomach3 | 14 (6.60) |

Patients were divided into either the postoperative sepsis group (n = 48) or the non-postoperative sepsis group (n = 164). Following univariate analysis (Table 1), 16 factors differed between the two groups: Age, temperature, heart rate, mean arterial pressure, ascites incidence, serum creatinine, white blood cell counts, C-reactive protein, colonic perforation, gastric perforation, time interval from abdominal pain to emergency surgery, preoperative American Society of Anesthesiologists score, incidence of malignant tumor-related perforation, perforation diameter, perforation repair, and digestive tract reconstruction.

Multiple logistic regression analysis confirmed that the time interval from abdominal pain to emergency surgery (OR = 1.021, 95%CI: 1.005-1.038, P = 0.006), colonic perforation (OR = 2.761, CI: 1.821-14.776, P = 0.007), perforation diameter (OR = 1.062, 95%CI: 1.007-1.121, P = 0.027), and incidence of malignant tumor-related perforation (OR = 5.384, 95%CI: 1.762-32.844, P = 0.021) were associated with postoperative sepsis (Table 3).

| Clinical variables | OR | 95%CI | P value |

| Age | 1.019 | 0.966-1.042 | 0.234 |

| Temperature | 2.160 | 0.998-4.147 | 0.053 |

| Heart rate | 1.047 | 0.996-1.104 | 0.071 |

| Mean arterial pressure | 0.946 | 0.349-1.108 | 0.171 |

| Serum creatinine | 0.997 | 0.987-1.006 | 0.527 |

| White blood cells | 1.037 | 0.938-1.147 | 0.479 |

| C-reactive protein | 1.006 | 0.997-1.014 | 0.245 |

| Ascites | 1.316 | 0.102-14.982 | 0.996 |

| Diameter of perforation | 1.062 | 1.007-1.121 | 0.027 |

| Gastric perforation | 0.897 | 0.854-1.175 | 0.089 |

| Colonic perforation | 2.761 | 1.821-14.776 | 0.007 |

| Preoperative ASA score | 1.273 | 0.637-2.542 | 0.494 |

| Time interval from abdominal pain to emergency surgery | 1.021 | 1.055-1.038 | 0.006 |

| Repair of perforation | 0.961 | 0.247-3.739 | 0.954 |

| Digestive tract reconstruction1 | 6.460 | 0.907-46.007 | 0.063 |

| Malignant tumor-related perforation | 5.384 | 1.762-32.844 | 0.021 |

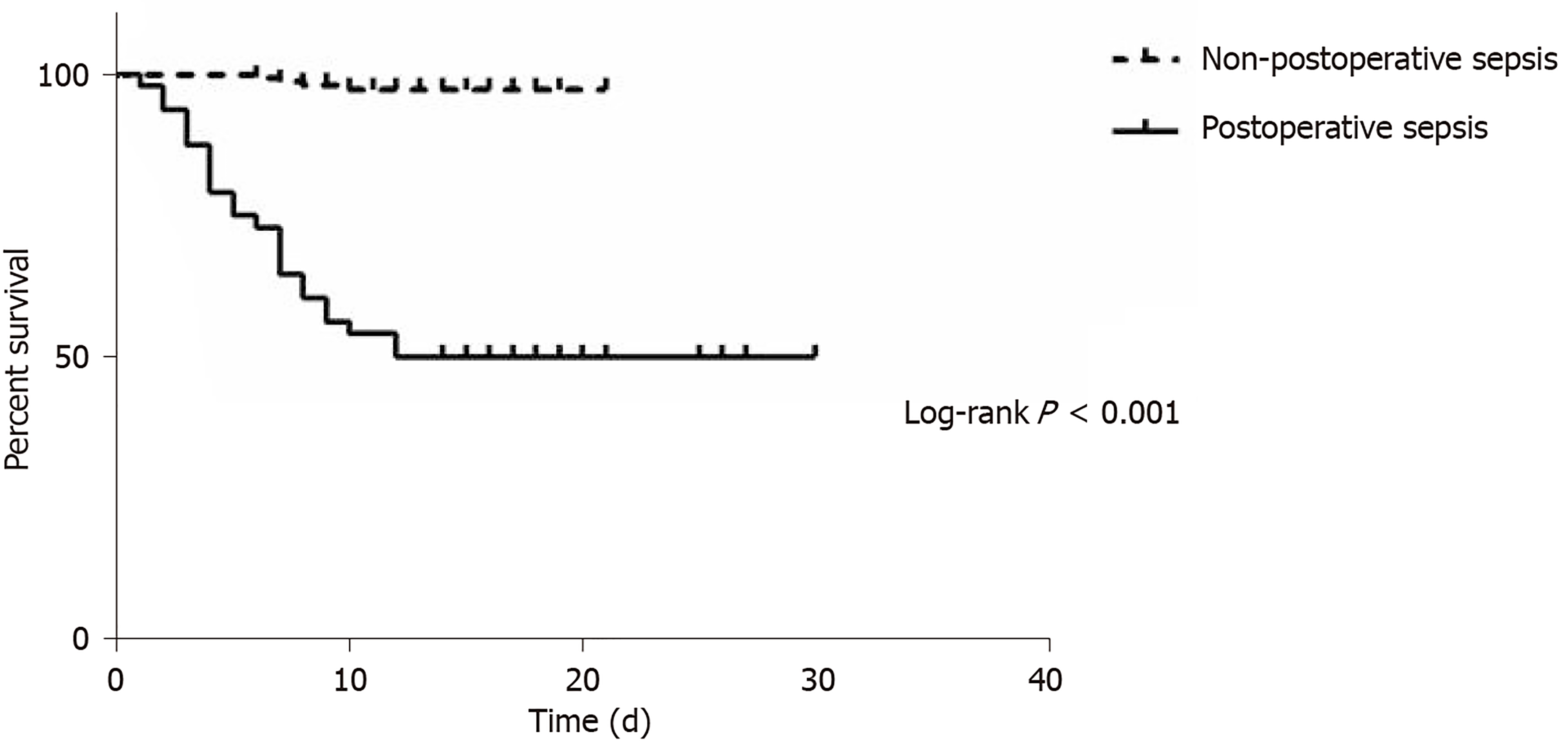

The time interval from emergency surgery to sepsis was 1 d (range, 1-2 d). Twenty-four patients (50%) died in the postoperative sepsis group, whereas only 4 died (2.44%) in the non-postoperative sepsis group (Table 4). Mortality was higher in the postoperative sepsis group than in the non-postoperative sepsis group (Figure 1; P < 0.001). Length of stay in survivors was longer in the postoperative sepsis group than in the non-postoperative sepsis group (20.96 ± 4.97 d vs 11.69 ± 2.8 d; P < 0.001).

| Clinical variables | Postoperative sepsis group | Non-postoperative sepsis group | P value |

| Death, n (%) | 24 (50) | 4 (2.44) | < 0.001 |

| Septic shock | 22 (45.83) | 0 (0) | < 0.001 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0 (0) | 3 (1.83) | 1.000 |

| Heart failure | 2 (4.17%) | 1 (0.610%) | 0.129 |

| LOS of survivors (mean ± SD, d) | 20.96 ± 4.97 | 11.69 ± 2.8 | < 0.001 |

GIP is a common but fatal acute abdominal injury. The primary method for treating GIP is emergency surgery[8,9]. Prior studies showed that the incidence of sepsis due to GIP reached 20%-73%[12,14-16], and mortality due to GIP-induced sepsis was 30%-50%[12,14-16]. In the present study, the incidence of sepsis was 22.6%, and the mortality due to sepsis was 50%. Although a new definition of sepsis has been introduced, mortality was not significantly increased, possibly because of the differences between participants in our study and those in previous studies.

The present study included 161 men and 51 women with GIP, with a male/female ratio of approximately 3:1. The male/female ratio was also high in other studies of GIP[16,18]. Recent research on peptic ulcer perforation found an even higher male/female ratio of 10:1[14]. Sivaram et al[14] found that being female was a risk factor for mortality in patients with peptic ulcer perforations. However, Sivaram’s research was focused on upper gastrointestinal ulcer perforations. Our study included jejunal/ileal and colonic perforations as well as trauma and tumor-related perforations; this may have caused the difference in the male/female ratio.

In our study, colonic perforation was associated with postoperative sepsis. The colon contains more bacteria; thus, these patients will absorb more toxins[19,20], resulting in a higher risk for postoperative complications, which has been demonstrated in many studies. The time interval from abdominal pain to emergency surgery was a risk factor for postoperative sepsis in our study. A longer interval may have caused more intestinal fluid to spill and be absorbed into the blood, possibly leading to postoperative sepsis. The occurrence of sepsis would lead to high mortality[14,15]. Some studies found that a delay of more than 24 h is associated with mortality and morbidity due to GIP[15,21], thus illustrating the importance of the time interval from abdominal pain to emergency surgery. Perforation diameter is also associated with prognosis. Sivaram et al[14] revealed that perforation diameters > 1.0 cm led to poor outcomes. Taş et al[21] reported that patients with perforation diameters > 0.5 cm were at high risk for postoperative morbidity. Our research showed that the perforation diameter may be associated with postoperative sepsis, which was consistent with previous studies.

The present study also revealed that malignant tumor-related perforations may be associated with postoperative sepsis. The edges of malignant gastrointestinal ulcers are more irregular or asymmetric; folds appear more disrupted and “moth-eaten” near the crater edge and/or are clubbed or fused and more crisp or tough than benign ulcers[22]. Consequently, malignant tumor-related perforations are more difficult to treat than benign ulcer-related perforations[22]. In our study, 30 patients had malignancy-related perforations. The operation duration was longer for patients with malignancy-related tumor perforations (3 h[3,4] vs 2 h[1,2]; P < 0.001). In addition, no patients with malignant tumor-related perforations underwent repair procedures. The surgical procedures included digestive tract reconstruction (gastrectomy + gastrojejunostomy, n = 14), gastrectomy (n = 4 patients with malignant gastric tumors), and resection + ostomy (n = 12 patients, 9 with a partial colectomy + colostomy and 3 with a partial colectomy and anastomosis + enterostomy). Studies of damage control[23] have shown that complex surgical procedures can lead to poor prognoses. In summary, patients with malignant tumor-related perforations are more likely to experience postoperative sepsis with higher mortality rates.

Our study had some limitations. First, because the study was retrospective, some selection bias existed. Second, procalcitonin was not analyzed, which might be regarded as an infection index. Third, the number of patients in the group with postoperative sepsis was very different from that in the non-postoperative sepsis group. In addition, the causes of the perforation would partially influence the surgical procedure, which may make some factors less prominent. Subgroup studies should be performed in the future.

In conclusion, the time interval from abdominal pain to emergency surgery, colonic perforation, perforation diameter, and malignant tumor-related perforation incidence were risk factors for postoperative sepsis in patients with GIP.

Gastrointestinal perforation (GIP) is a common acute abdominal injury. It usually requires active rescue in the intensive care unit with an emergency laparotomy. The definition of sepsis was revised in 2016 (sepsis 3.0) to better reflect the prognosis and organ function damage rather than being defined as infection-induced systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Once sepsis occurs, the prognosis worsens, and few studies have focused on the risk factors for postoperative sepsis in patients with GIP.

In 2016, the definition of sepsis was revised. According to the revision, patients with postoperative sepsis would be at a higher risk for death. As a result, we thought an investigation of the risk factors for postoperative sepsis was very necessary.

This study aimed to investigate the risk factors for postoperative sepsis in patients with GIP.

From January 2016 to December 2018, the medical records of patients with GIP, receiving emergency surgery, were retrospectively reviewed and analyzed. Risk factors for postoperative sepsis in patients with GIP were evaluated.

A total of 212 patients were eligible. The prevalence of postoperative sepsis was 22.6% [95% confidence interval (CI): 17.0%-28.3%, n = 48]. The time interval from abdominal pain to emergency surgery [odds ratio (OR) = 1.021, 95%CI: 1.005-1.038, P = 0.006], colonic perforation (OR = 2.761, CI: 1.821-14.776, P = 0.007), diameter of perforation (OR = 1.062, 95%CI: 1.007-1.121, P = 0.027), and the incidence of malignant tumor-related perforation (OR = 5.384, 95%CI: 1.762-32.844, P = 0.021) were associated with postoperative sepsis.

The time interval from abdominal pain to emergency surgery, colonic perforation, diameter of perforation, and the incidence of malignant tumor-related perforation were risk factors for postoperative sepsis in patients with GIP.

A further study plans to include more subjects and the development of a prediction model for postoperative sepsis, in order to identify a truly accurate diagnostic method suitable for clinical use.

Manuscript source: Invited Manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: García-Elorriaga G S-Editor: Tang JZ L-Editor: Webster JR E-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Chen H, Zhang H, Li W, Wu S, Wang W. Acute gastrointestinal injury in the intensive care unit: a retrospective study. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2015;11:1523-1529. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | Závada J, Lunt M, Davies R, Low AS, Mercer LK, Galloway JB, Watson KD, Symmons DP, Hyrich KL; British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register (BSRBR) Control Centre Consortium. The risk of gastrointestinal perforations in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with anti-TNF therapy: results from the BSRBR-RA. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:252-255. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Xie F, Yun H, Bernatsky S, Curtis JR. Brief Report: Risk of Gastrointestinal Perforation Among Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients Receiving Tofacitinib, Tocilizumab, or Other Biologic Treatments. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:2612-2617. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Curtis JR, Xie F, Chen L, Spettell C, McMahan RM, Fernandes J, Delzell E. The incidence of gastrointestinal perforations among rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:346-351. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Nassour I, Fang SH. Gastrointestinal perforation. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:177-178. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Holmer C, Mallmann CA, Musch MA, Kreis ME, Gröne J. Surgical Management of Iatrogenic Perforation of the Gastrointestinal Tract: 15 Years of Experience in a Single Center. World J Surg. 2017;41:1961-1965. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Jin YJ, Jeong S, Kim JH, Hwang JC, Yoo BM, Moon JH, Park SH, Kim HG, Lee DK, Jeon YS, Lee DH. Clinical course and proposed treatment strategy for ERCP-related duodenal perforation: a multicenter analysis. Endoscopy. 2013;45:806-812. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Verlaan T, Voermans RP, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Bemelman WA, Fockens P. Endoscopic closure of acute perforations of the GI tract: a systematic review of the literature. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:618-28.e5. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Baron TH, Song LM, Ross A, Tokar JL, Irani S, Kozarek RA. Use of an over-the-scope clipping device: multicenter retrospective results of the first U.S. experience (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:202-208. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Mulari K, Leppäniemi A. Severe secondary peritonitis following gastrointestinal tract perforation. Scand J Surg. 2004;93:204-208. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Karlsson S, Varpula M, Ruokonen E, Pettilä V, Parviainen I, Ala-Kokko TI, Kolho E, Rintala EM. Incidence, treatment, and outcome of severe sepsis in ICU-treated adults in Finland: the Finnsepsis study. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:435-443. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Wickel DJ, Cheadle WG, Mercer-Jones MA, Garrison RN. Poor outcome from peritonitis is caused by disease acuity and organ failure, not recurrent peritoneal infection. Ann Surg. 1997;225:744-753. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Wang LW, Lin H, Xin L, Qian W, Wang TJ, Zhang JZ, Meng QQ, Tian B, Ma XD, Li ZS. Establishing a model to measure and predict the quality of gastrointestinal endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:1024-1030. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Sivaram P, Sreekumar A. Preoperative factors influencing mortality and morbidity in peptic ulcer perforation. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2018;44:251-257. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Kocer B, Surmeli S, Solak C, Unal B, Bozkurt B, Yildirim O, Dolapci M, Cengiz O. Factors affecting mortality and morbidity in patients with peptic ulcer perforation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:565-570. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Ye-Ting Z, Dao-Ming T. Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) and the Pattern and Risk of Sepsis Following Gastrointestinal Perforation. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:3888-3894. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Abraham E. New Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock: Continuing Evolution but With Much Still to Be Done. JAMA. 2016;315:757-759. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 18. | Gao Y, Yu KJ, Kang K, Liu HT, Zhang X, Huang R, Qu JD, Wang SC, Liu RJ, Liu YS, Wang HL. Procalcitionin as a diagnostic marker to distinguish upper and lower gastrointestinal perforation. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:4422-4427. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 19. | Sarici IS, Topuz O, Sevim Y, Sarigoz T, Ertan T, Karabıyık O, Koc A. Endoscopic Management of Colonic Perforation due to Ingestion of a Wooden Toothpick. Am J Case Rep. 2017;18:72-75. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 20. | Bohr J, Larsson LG, Eriksson S, Järnerot G, Tysk C. Colonic perforation in collagenous colitis: an unusual complication. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17:121-124. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 21. | Taş İ, Ülger BV, Önder A, Kapan M, Bozdağ Z. Risk factors influencing morbidity and mortality in perforated peptic ulcer disease. Ulus Cerrahi Derg. 2015;31:20-25. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |