Published online Feb 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i3.535

Peer-review started: December 8, 2019

First decision: December 23, 2019

Revised: January 1, 2020

Accepted: January 8, 2020

Article in press: January 8, 2020

Published online: February 6, 2020

Processing time: 58 Days and 18.7 Hours

Splenic peliosis is a disease characterized by widespread blood-filled cystic cavities within the parenchyma. Patients with this disease are usually asymptomatic; therefore, spontaneous or trauma-related rupture of the hemorrhagic cysts can occasionally cause life-threatening hemorrhagic shock.

A 51-year-old male patient with abdominal pain visited our emergency medical center two times with an interval of 2 mo. The patient was discharged from the hospital without treatment at his first visit; however, at the time of second admission, the hemoperitoneum with multiple cystic lesions of the spleen was found incidentally on the abdomen computed tomography scan. Since the patient was stable hemodynamically, a scheduled surgery was performed. The operative findings were consistent with splenic peliosis, and laparoscopic splenectomy was performed to prevent recurrent rupture of the hemorrhagic cysts.

Splenic peliosis is extremely rare, and we suggest splenectomy is necessarily required as a definite treatment for ruptured splenic peliosis to rescue patients with hemodynamic instability and to prevent recurrent rupture of hemorrhagic cysts in patients with stable hemodynamics.

Core tip: Peliosis is a rare disease entity characterized by widespread blood-filled cystic cavities within the parenchymal organs. Patients with splenic peliosis are usually asymptomatic; however, incidental or trauma-related rupture of the hemorrhagic cysts may result in fatal outcomes. Splenectomy offers the advantage of a definite histological diagnosis with the complete elimination of the risk of recurrent hemorrhage.

- Citation: Rhu J, Cho J. Ruptured splenic peliosis in a patient with no comorbidity: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(3): 535-539

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i3/535.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i3.535

Peliosis is a rare disease entity characterized by widespread blood-filled cystic cavities within the parenchymal organs[1]. The word “pelios” originates from the Greek language, meaning dusky or purple and was first used by Wagner[2] in 1861. The liver is the most commonly involved organ, and isolated splenic peliosis is extremely uncommon. Splenic peliosis is related to chronic illnesses, such as malignancy, infections, and ingestion of anabolic steroids[3]. Patients with splenic peliosis are usually asymptomatic; however, incidental or trauma-related rupture of the hemorrhagic cysts may result in fatal outcomes[4].

We recently treated a patient who was diagnosed with splenic peliosis. Definitive treatment was delayed in this patient due to diagnostic uncertainty, and the outcome might be fatal unless the patient received the timely operation. Here, we report on this critical case to discuss an optimized treatment strategy for splenic peliosis.

A 51-year-old man visited the emergency medical center of our hospital with abdominal pain and distension.

This patient visited our hospital based on a complaint of chest pain two months ago. At admission, his vital signs were stable, and there were no indications of abdominal tenderness or rebound tenderness suggestive of peritonitis. The chest and abdomen radiographs, electrocardiogram, and cardiac markers also showed no abnormalities; therefore, he was discharged from the hospital after receiving routine education. Two months later, this patient returned to our emergency medical center with abdominal pain and distension.

This patient had no comorbidities.

The patient had no personal history and the family history was negative for inherent disease.

The patient was hemodynamically stable, and there was little tenderness and rebound tenderness on his abdomen, although he complained of slight abdomen discomfort.

No abnormalities were found on the laboratory examinations, including complete blood cell count, cardiac markers, and coagulation profile.

As we could not determine the possible diagnosis, abdomen computed tomography (CT) was performed immediately, and the result revealed multiple hemorrhagic cysts on the spleen with a moderate amount of hemoperitoneum (Figure 1).

The abdomen CT confirmed multiple hemorrhagic cysts on the spleen with a moderate amount of hemoperitoneum.

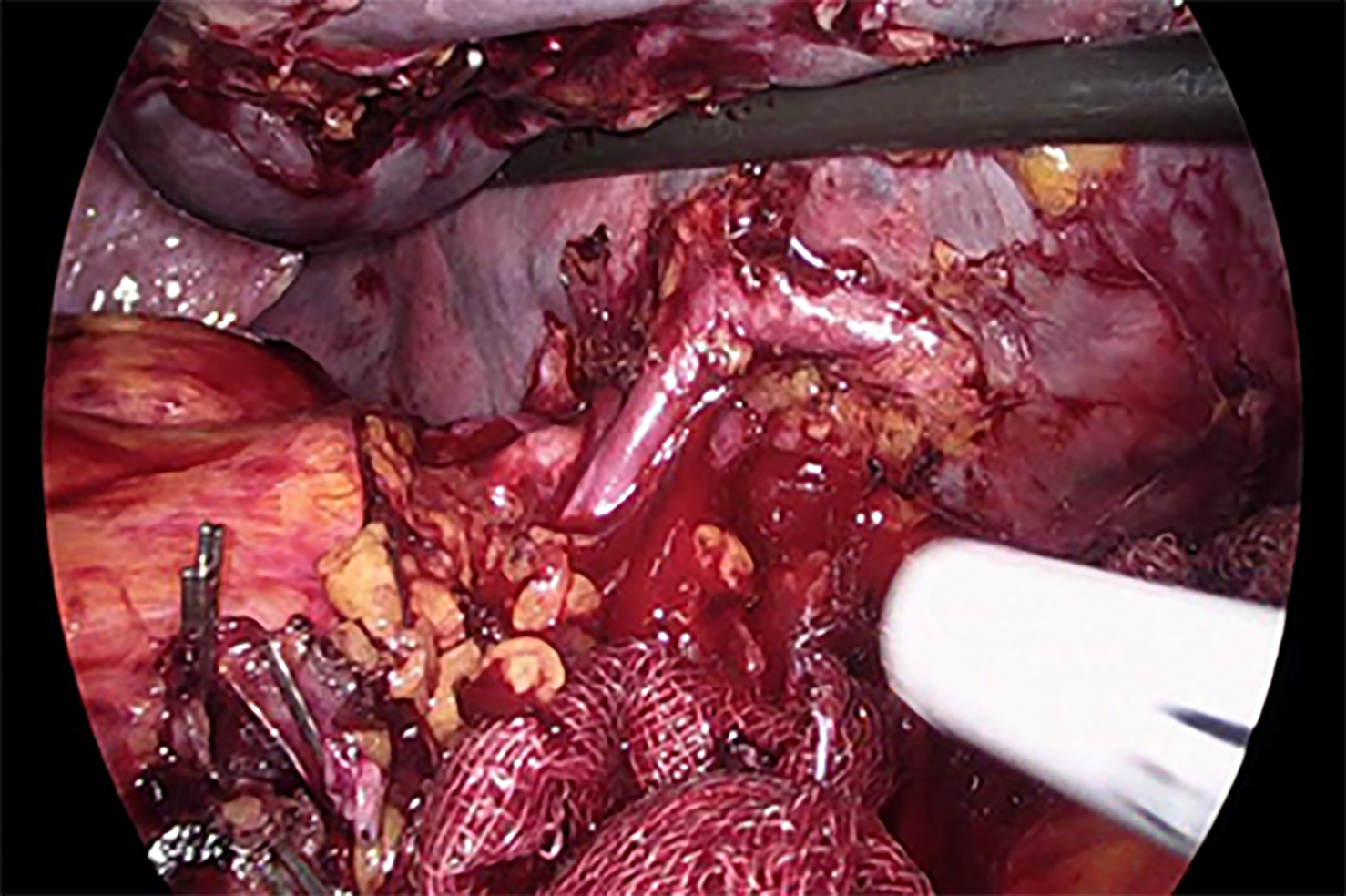

Since the patient’s vital signs were stable and there were no signs of peritonitis, we opted not to perform emergent surgery. Instead, the patient was admitted to our surgical intensive care unit and received a perioperative medical checkup with close monitoring for any clinical deterioration. On the second day of hospitalization, the patient’s clinical condition remained stable, and the scheduled operation was performed laparoscopically for a definite diagnosis and necessary treatment. The peritoneal cavity was filled with clotted blood, and the spleen was congestive with tortuous, overdeveloped vessels, which exhibited easy-touch-bleeding tendency (Figure 2). Although there was no evidence of active or ongoing bleeding on the spleen, we decided to perform a splenectomy because recurrent rupture of hemorrhagic cysts was strongly anticipated.

The operation was completed without complications, and the patient was discharged from the hospital on the 7th postoperative day. There was no evidence of predisposing factors for splenic peliosis in this patient.

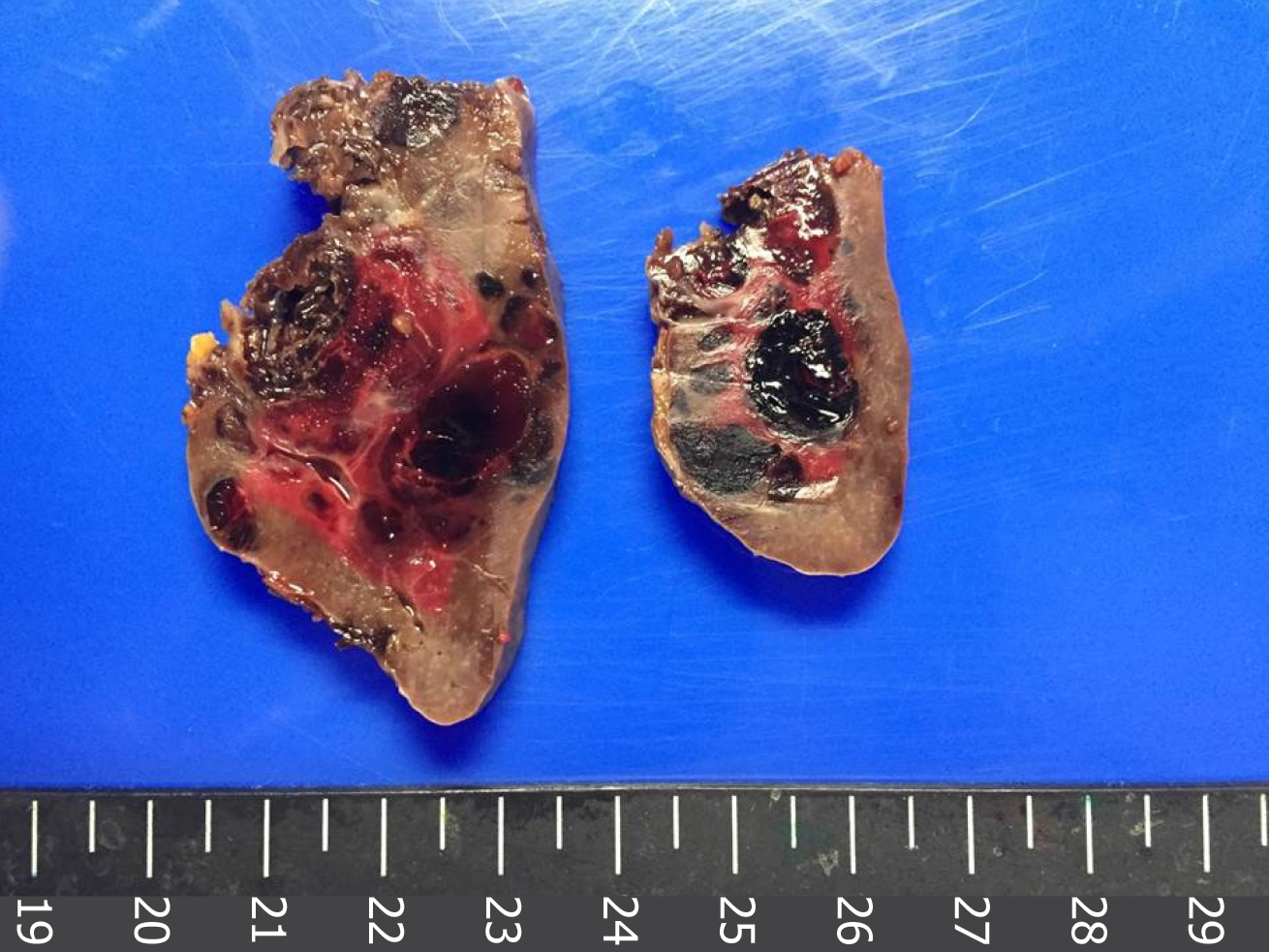

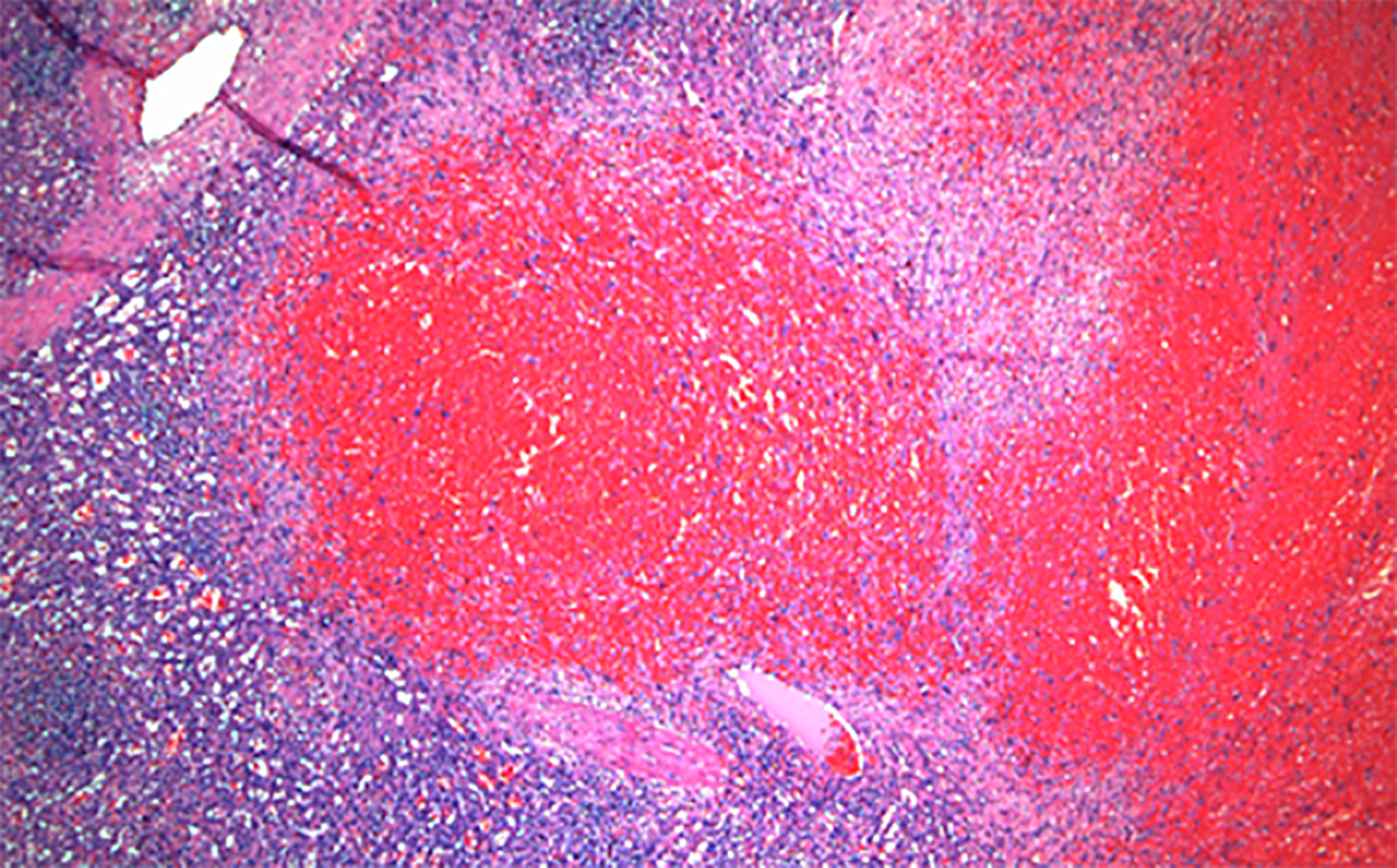

On gross inspection, the size of the specimen was 9.5 cm × 5.5 cm × 2.0 cm, and there were multiple cysts measuring up to 1.0 cm in diameter that were filled with clotted blood (Figure 3). On microscopic examination, the blood-filled cystic lesions in the splenic parenchyma were well demarcated and distributed in the red pulp congestion. No vascular endothelial cells were observed, and normal lining cells disappeared in the wall (Figure 4). There was no evidence of neoplastic vessels or tumor cells.

Peliosis may develop in the liver, spleen, abdominal lymph nodes, bone marrow, kidney, adrenal glands, lung, and pancreas, resulting in abnormally distended blood-filled cavities in the sinusoidal space[5,6]. This condition is now defined histopathologically. The precise mechanisms that lead to this condition remain largely unknown, though it seems to be associated with chronic debilitating disorders, such as neoplastic diseases, tuberculosis, human immunodeficiency virus infection, hematologic disorders, and the use of anabolic steroids or oral contraceptives[5,7]. Most cases of splenic peliosis are incidentally found at the autopsy or during imaging studies for other diseases, and most of them are associated with peliosis of the liver[8]. In cases with peliosis hepatis, elective surgery can be rarely performed as no preoperative examinations are available in making the diagnosis, although the hepatic resection is necessarily required for the definitive treatment[9]. Pathologically, splenic peliosis is differentiated from other splenic cystic lesions by multiple blood-filled cysts that are massively scattered in the red pulp, with preferential involvement of the para-follicular areas of the spleen[10]. Patients with this condition are often initially asymptomatic; therefore, early recognition and withdrawal of offending agents are crucial. In cases with the rupture of surface lesions, which can occur spontaneously or by minor trauma, prompt surgical management is required[11]. Splenectomy offers the advantage of a definite histological diagnosis with the complete elimination of the risk of recurrent hemorrhage, and laparoscopic splenectomy has reduced morbidity significantly compared to open surgery[12]. However, prophylactic splenectomy is still under debate. Since the spleen plays a key role in regulating the immune system and endocrine function associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease[13], the decision for the total splenectomy should be made with caution after estimating the risk and benefit.

In our case, the diagnosis was difficult because we did not include a hemoperitoneum in the differential diagnoses. Rather, the symptoms and signs of this patient suggested coronary artery disease or peptic ulcer disease. Moreover, this patient did not have any predisposing conditions of splenic peliosis, and the hemodynamic parameters showed no abnormalities with normal laboratory results. Consequently, the ruptured splenic peliosis in this patient could be incidentally diagnosed on the screening abdomen CT scan. If the rupture of hemorrhagic cysts was massive, leading to critical hemorrhagic shock, the patient might not survive or would experience a difficult clinical course because we were not prepared for sudden clinical deterioration. In this respect, we suggest that rupture of the hemorrhagic cysts in the splenic peliosis can occur spontaneously, even in patients with no comorbidities, and the clinical manifestations can be mild; therefore, the surgeon should be aware of the possibility of splenic peliosis in the case of unexplained abdominal or chest pain. In addition, we suggest that premature discharge from the hospital due to a misdiagnosis may lead to a fatal outcome, and early surgical intervention performed before hemorrhagic shock develops or at the first sign of surgical abdomen can prevent more severe complications in ruptured splenic peliosis.

Splenic peliosis might be too rare to be included in the differential diagnoses of unspecified abdominal pain. However, since the rupture of hemorrhagic cysts can cause fatal outcomes, suspicion of any possibility in patients with recurrent or unexplained abdominal pain is crucial, even if the clinical clue shows discordances initially. Under the suspicion of surgical emergency, a thorough diagnostic work-up should be performed, and splenic peliosis would be found incidentally. Finally, timely definite splenectomy can rescue the patient.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Can G, D'Orazi V, Tarantino G S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: A E-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Tsokos M, Erbersdobler A. Pathology of peliosis. Forensic Sci Int. 2005;149:25-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wagner E. Ein fall von Blutcysten in der Leber. Arc Heilkunde. 1861;2:369-370. |

| 3. | Celebrezze JP, Cottrell DJ, Williams GB. Spontaneous splenic rupture due to isolated splenic peliosis. South Med J. 1998;91:763-764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Begum S, Khan MR. Splenic peliosis and rupture−A surgical emergency: Case report and review of the available literature. J Appl Hematol. 2016;7:143-147. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Diebold J, Audouin J. Peliosis of the spleen. Report of a case associated with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, presenting with spontaneous splenic rupture. Am J Surg Pathol. 1983;7:197-204. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Ichijima K, Kobashi Y, Yamabe H, Fujii Y, Inoue Y. Peliosis hepatis. An unusual case involving multiple organs. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1980;30:109-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Raghavan R, Alley S, Tawfik O, Webb P, Forster J, Uhl M. Splenic peliosis: a rare complication following liver transplantation. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:1128-1131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Joseph F, Younis N, Haydon G, Adams DH, Wynne S, Gillet MB, Maurice YM, Lipton ME, Berstock D, Jones IR. Peliosis of the spleen with massive recurrent haemorrhagic ascites, despite splenectomy, and associated with elevated levels of vascular endothelial growth factor. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:1401-1406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Crocetti D, Palmieri A, Pedullà G, Pasta V, D'Orazi V, Grazi GL. Peliosis hepatis: Personal experience and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:13188-13194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Adachi K, Ui M, Nojima H, Takada Y, Enatsu K. Isolated splenic peliosis presenting with giant splenomegaly and severe coagulopathy. Am J Surg. 2011;202:e17-e19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kohr RM, Haendiges M, Taube RR. Peliosis of the spleen: a rare cause of spontaneous splenic rupture with surgical implications. Am Surg. 1993;59:197-199. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Katkhouda N, Mavor E. Laparoscopic splenectomy. Surg Clin North Am. 2000;80:1285-1297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tarantino G, Savastano S, Capone D, Colao A. Spleen: A new role for an old player? World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:3776-3784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |