Published online Dec 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i24.6537

Peer-review started: September 27, 2020

First decision: October 18, 2020

Revised: October 24, 2020

Accepted: November 4, 2020

Article in press: November 4, 2020

Published online: December 26, 2020

Processing time: 83 Days and 1.4 Hours

Primary duodenal tuberculosis is very rare. Due to a lack of specificity for its presenting symptoms, it is easily misdiagnosed clinically. Review of the few case reports and literature on the topic will help to improve the overall understanding of this disease and aid in differential diagnosis to improve patient outcome.

A 71-year-old man with a 30-plus year history of bronchiectasis and bronchitis presented to the Gastroenterology Department of our hospital complaining of intermittent upper abdominal pain. Initial imaging examination revealed a duodenal space-occupying lesion; subsequent upper abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography indicated duodenal malignant tumor. Physical and laboratory examinations showed no obvious abnormalities. In order to confirm further the diagnosis, electronic endoscopy was performed and tissue biopsies were taken. Duodenal histopathology showed granuloma and necrosis. In-depth tuberculosis-related examination did not rule out tuberculosis, so we initiated treatment with anti-tuberculosis drugs. At 6 mo after the anti-tuberculosis drug course, there were no signs of new development of primary lesions by upper abdominal computed tomography, and no complications had manifested.

This case emphasizes the importance of differential diagnosis for gastrointestinal diseases. Duodenal tuberculosis requires a systematic examination and physician awareness.

Core Tip: Tuberculosis is a major threat to human health, and its incidence continues to rise, especially in developing countries. The gastrointestinal form of tuberculosis, however, is rare. We report here the case of an elderly male, whose primary duodenal tuberculosis was misdiagnosed as tumor. Despite the imaging diagnosis of malignant tumor, tissue biopsy did not support that diagnosis. After a series of additional tests, the patient was treated with anti-tuberculosis drugs for a period of 6 mo. Follow-up showed no new disease progression and no other complications. This case emphasizes the importance of differential diagnosis of duodenal space-occupying disease.

- Citation: Zhang Y, Shi XJ, Zhang XC, Zhao XJ, Li JX, Wang LH, Xie CE, Liu YY, Wang YL. Primary duodenal tuberculosis misdiagnosed as tumor by imaging examination: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(24): 6537-6545

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i24/6537.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i24.6537

Tuberculosis is a worldwide health problem, with a particularly high incidence in developing countries. The abdominal form represents the third largest extrapulmonary manifestation of tuberculosis[1]. In abdominal tuberculosis, as the symptoms are not obvious, gastrointestinal tuberculosis is especially difficult to diagnose. In addition, primary duodenal tuberculosis is very rare, with few cases reported in the literature, and easy to misdiagnose. We report a case of primary duodenal tuberculosis misdiagnosed as a malignant tumor. The patient was a 71-year-old male without any characteristics of pulmonary tuberculosis.

A 71-year-old man presented to the Gastroenterology Department of our hospital complaining of symptoms of intermittent upper abdominal pain and occasional acid reflux (heartburn). He denied any fever or night sweats but reported unintentional weight loss of about 2 kg within a month.

The patient’s symptoms started 1 mo prior to presentation but had worsened over the last 1 wk.

The patient had a history of intermittent medication for bronchiectasis and bronchitis for more than 30 years, with no known drug allergies. He denied any other history of hypertension, coronary heart disease, and diabetes. He declared having no special physical discomfort and not attending regular physical examinations.

The patient denied any family history.

The initial vital sign examination showed normal body temperature (36.4 °C) and regular heart rate (78 beats per min), respiratory rate (18 breaths per min), and blood pressure (118/72 mmHg). Body weight was 73 kg, and height was 168 cm. During the physical examination, a slight tenderness was found under the xiphoid process and upper abdomen. Moreover, there were no palpable lymphadenopathy or mass and no other remarkable findings of positive signs (e.g., McBurney's point tenderness, rebound tenderness and muscle tension, and abnormalities of the cardio-pulmonary system).

After admission to the in-patient ward, laboratory examinations were carried out and included tests for blood routine, stool routine plus occult blood, liver and kidney function, electrolytes, blood coagulation function, and tumor markers. Endoscopy was ordered, and the preoperative examinations ruled out hepatitis B, hepatitis C, syphilis, and human immunodeficiency virus. The neutrophilic granulocyte percentage was high (75.1%; normal range: 45%-75%) as was the D-dimer level (1.26 mg/mL; normal range: 0-1 mg/mL). There was no remarkable finding in other hematologic tests.

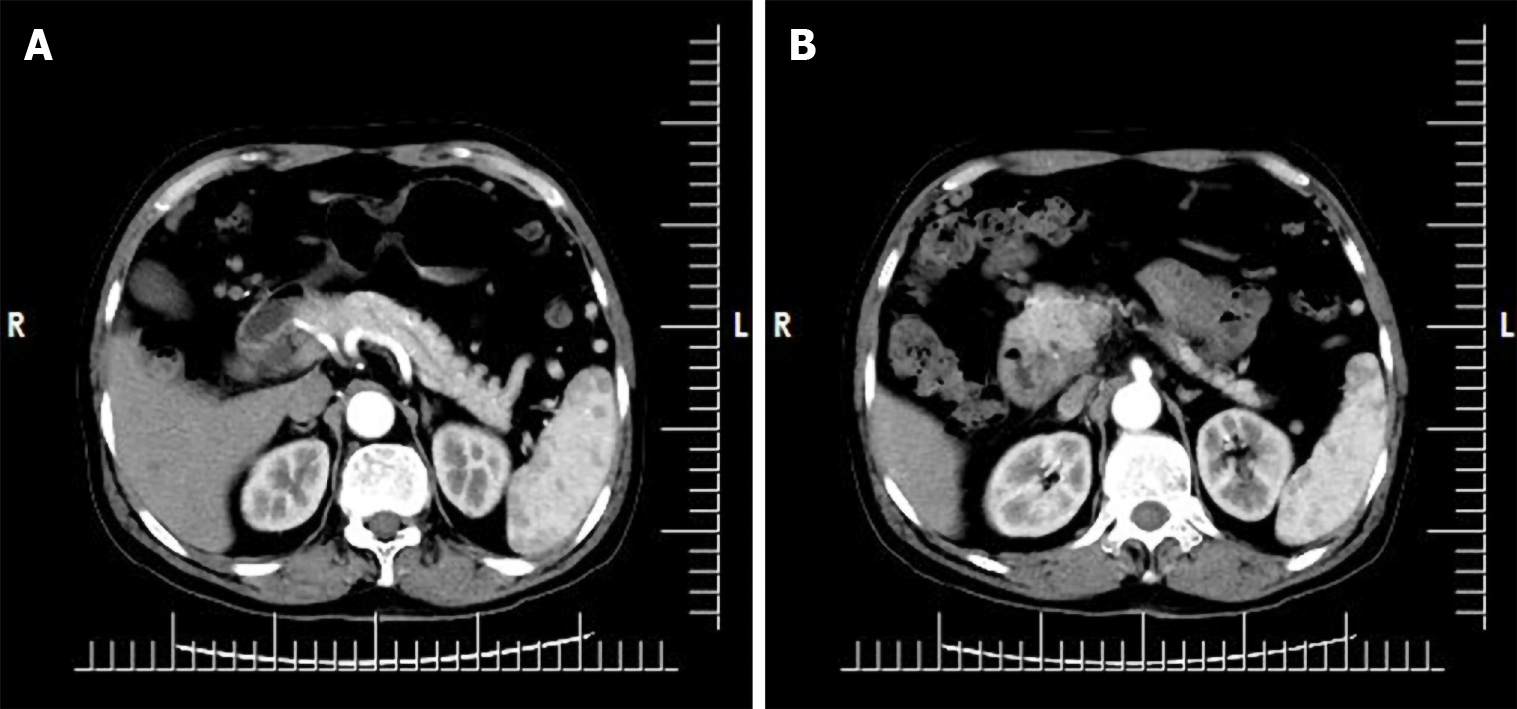

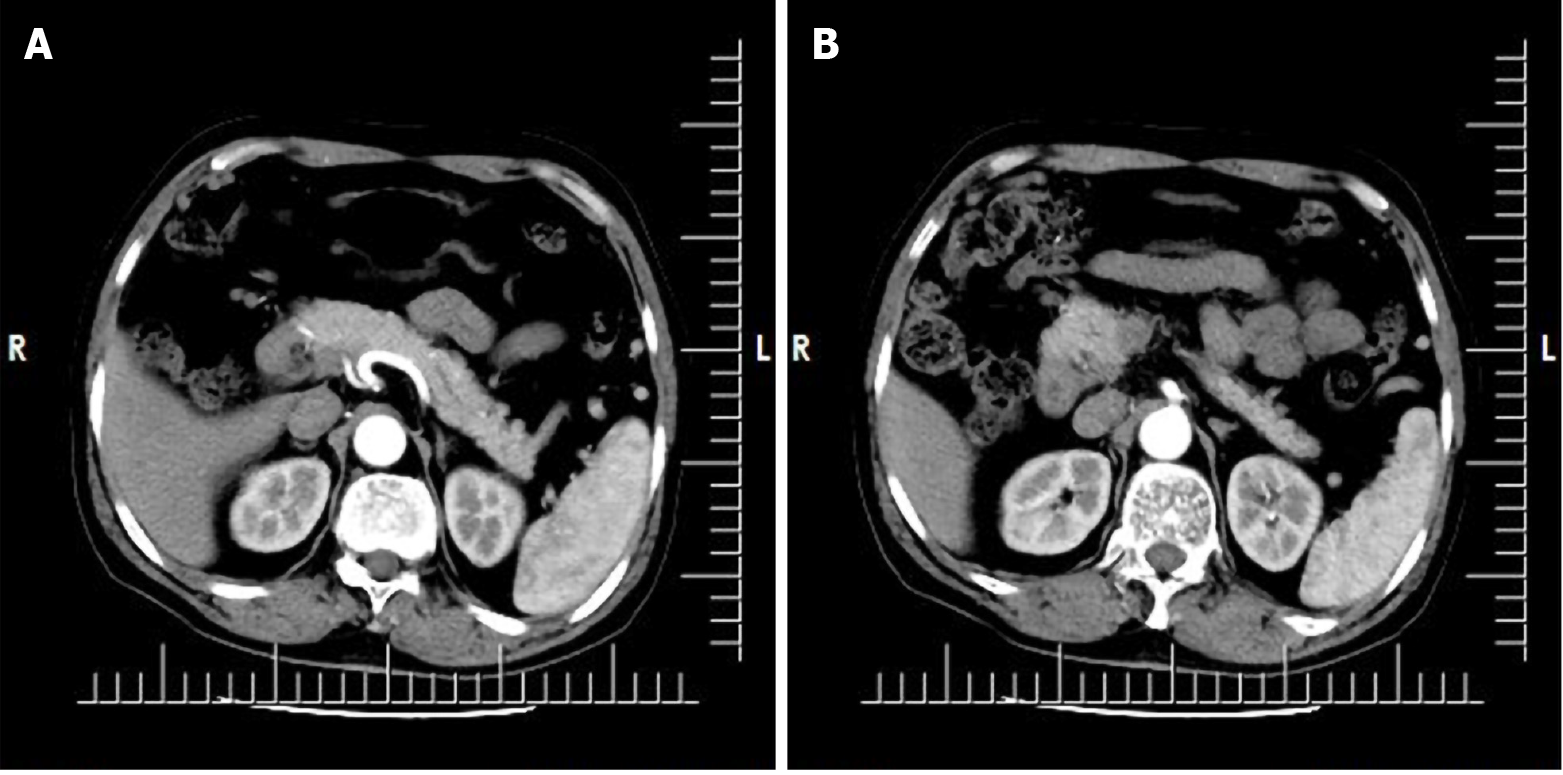

The patient had undergone upper abdominal computed tomography (CT) plain scan 1 wk prior to presentation at our hospital. Review of the scan showed diffuse thickening of the duodenal wall, duodenal inflammation, and an occupied space around the ampulla. The common bile duct was also found to be widened and the abdominal cavity to be more tortuous. The possibility of duodenal occupation led us to perform an enhanced CT examination of the upper abdomen after admission. The results suggested malignancy, possibly a duodenal carcinoma (Figure 1).

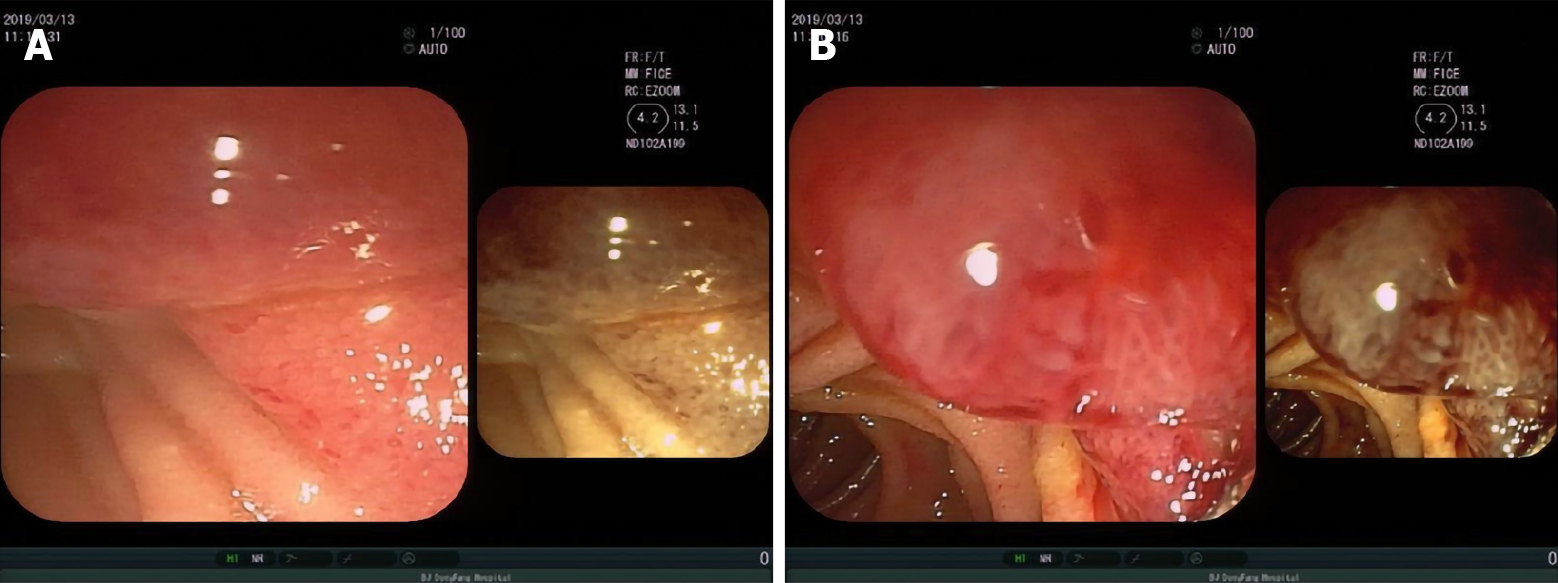

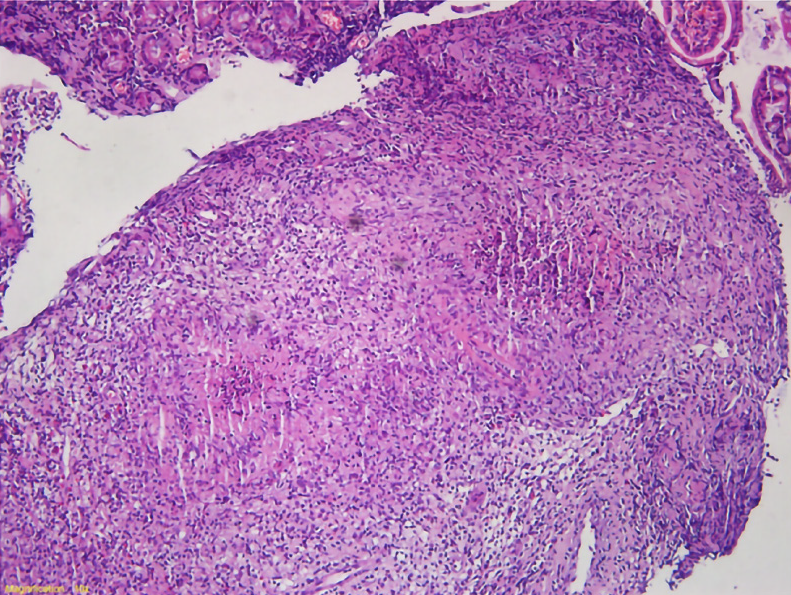

For further clarification, we performed electronic endoscopy. The gastroduodenoscopy showed an irregular lesion, with a markedly congested surface in the medial posterior wall of the descending duodenal region. Multiple biopsies were taken (Figure 2). The histopathological results suggested chronic inflammation of the small intestinal mucosal tissue, with granuloma and necrosis; these findings suggested the need to exclude tuberculosis as a potential diagnosis (Figure 3).

Thus, we subsequently performed tuberculosis-related examinations. The purified protein derivative skin test showed a 2 cm × 2 cm red dermatocolliculus with 1 cm × 1 cm indentation on the right forearm at 72 h, indicating a positive result. The lymphocyte culture plus interferon tests showed the lymphocyte culture plus interferon A increased to 112 and the lymphocyte culture plus interferon B increased to 268; although, the tuberculosis citrus antibody test yielded a negative result.

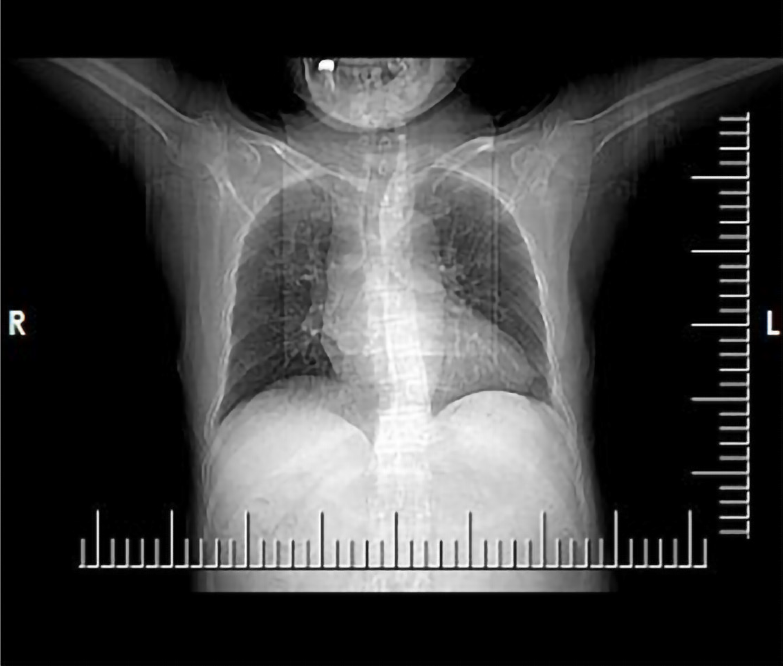

During the hospitalization, both chest CT and head CT were conducted as well. The chest CT plain scan showed no signs of tuberculosis but showed bronchiectasis in both lungs, with infection (Figure 4). The head CT plain scan showed no signs of cerebral tuberculosis but showed mild cerebral atrophy.

We conducted consultation on the duodenal histopathology with the Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and the Beijing Chest Hospital, Capital Medical University. The pathologic consultation with the former provided the same results as we had obtained, while the image consultation provided findings of the duodenal descending segment bowel wall having irregular thickening, with uneven strengthening and no enlarged lymph nodes in the abdominal and retroperitoneal regions. The latter performed additional deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) testing for tuberculosis bacilli in the duodenal tissue; the consequent recommendations were chronic granulomatous inflammation of the descending duodenum accompanied by slight necrosis and suppuration. The tuberculosis DNA test was redone and gave a negative result. Acid-fast staining, however, showed acid-fast bacilli (AFB) inside and outside the duodenal tissues. The pathological changes detected were in accordance with tuberculosis (Figure 5).

The final diagnosis of the presented case is highly-suspected primary duodenal tuberculosis.

Based on the above examination results, although tuberculosis DNA was undetectable, we still had high suspicion of duodenal tuberculosis; as such, we advised the patient to go to a specialist hospital for infectious diseases to start duodenal tuberculosis anti-tuberculosis treatment.

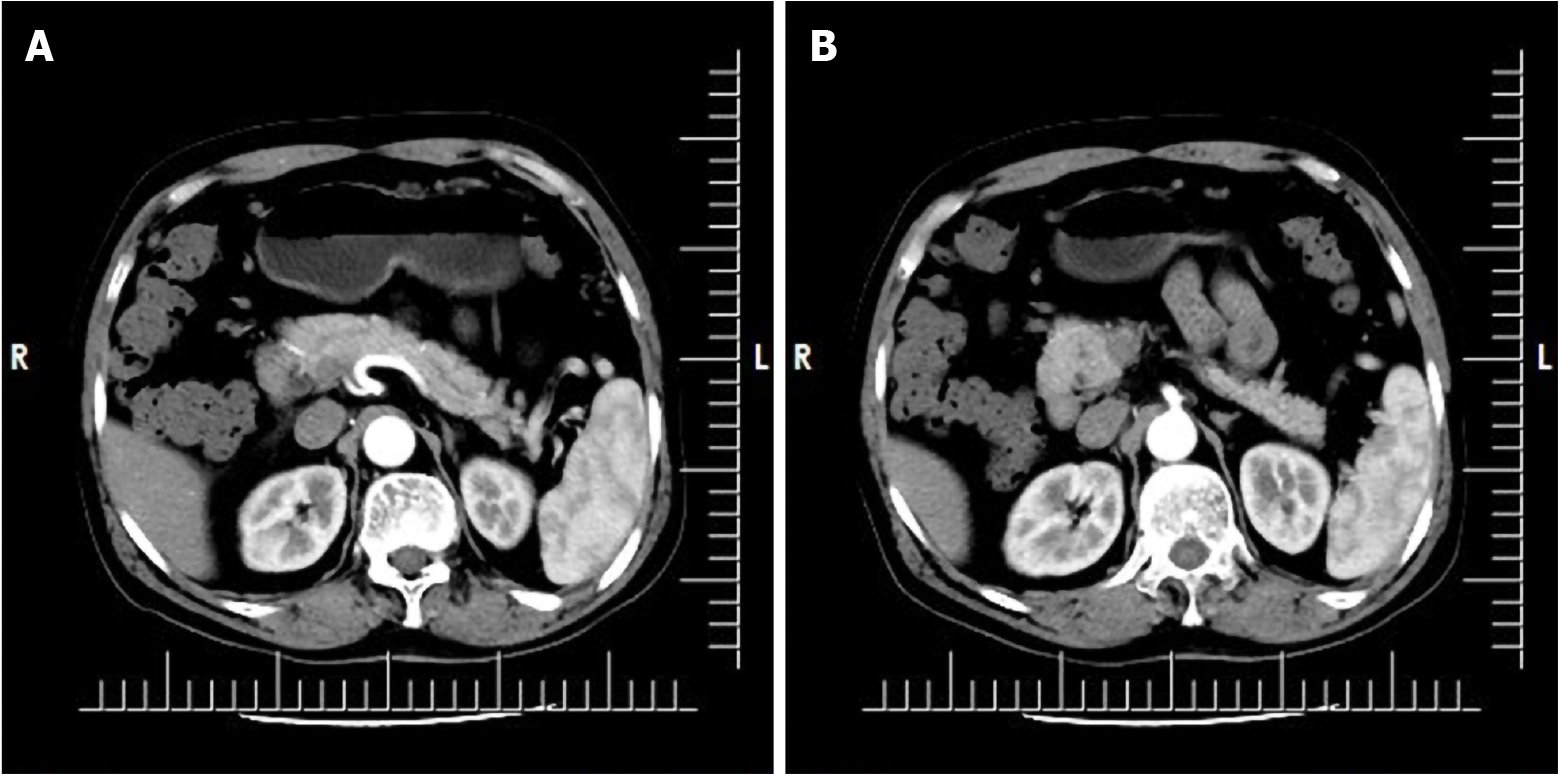

One month after discharge from our hospital, the patient submitted to a follow-up upper abdominal CT. It showed the descending wall of the duodenum to be slightly thickened (Image: 24), presenting an isopycnal shadow. The CT value was about 41 Hu, the edge was fuzzy, and the local convex to the lumen was about 1.3 cm thick, with an upper and lower diameter of 2.2 cm. The enhanced scan showed obvious uneven enhancement. The CT values of arterial stage, portal stage, and delayed stage were 63 Hu, 76 Hu, and 98 Hu, respectively, which were indistinguishable from pancreatic uncinate process (Figure 6).

The second upper abdominal CT examination was performed 6 mo after anti-tuberculosis drug treatment and yielded the same result as the one performed at 1 mo after discharge; the lesion in the duodenum was not significantly enlarged (Figure 7). After receiving anti-tuberculosis treatment for 6 mo, the patient had developed no obvious complications, such as intestinal obstruction, and the levels of liver and kidney function markers and whole blood cell count were normal.

The incidence of tuberculosis remains a worldwide problem, especially in developing countries. It is estimated that 1.7 billion people are infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis globally, and they are at risk of manifesting the disease symptomatically[1]. Abdominal tuberculosis is the third largest extrapulmonary manifestation of tuberculosis, accounting for 11%–16% of cases[2,3]. Tuberculosis can involve any part of the gastrointestinal tract, and the ileocecal area is the most common site, followed by the peritoneum and mesentery. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis is more common in hosts with low immune function. Gastric tuberculosis accounts for only 0.5%-3.0% of all gastrointestinal tuberculosis cases, while the incidence of gastroduodenal tuberculosis is reported as 0.5%[2]. When gastroduodenal tuberculosis does not coincide with any other lesions in the body, it is called primary gastroduodenal tuberculosis; being a very rare disease, few cases have been reported in the literature.

The possible causes of the rareness of duodenal tuberculosis may involve gastric acid, rapid transport of uptake microorganisms, sparse lymphoid follicles in the gastric wall, and integrity of the gastric mucosa[4,5]. For example, a study found that long-term use of histamine-2 blockers can increase the incidence of gastroduodenal tuberculosis[6]. Duodenal involvement may be exogenous, internal, or both[7,8]. The exogenous type may have primary duodenal involvement or compression due to enlarged peri-duodenal lymph nodes, while the endogenous type may show ulcerative, hypertrophic, or ulcerative hypertrophic lesions.

Duodenal tuberculosis is a diagnostic challenge because there are no specific symptoms. Its most likely misdiagnoses are peptic ulcer disease[9], inflammatory bowel disease[10], and malignancy[11]. Patients may have fever, weight loss, sweating, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, gastrointestinal bleeding, perforation, outlet obstruction, and other symptoms[12]. Duodenal obstruction with pain and vomiting is the most common manifestation, presenting in 60%-70% of cases. Obstruction can be caused by involvement of the bulbar or posterior mucosa or by exogenous compression of the perigastric or periduodenal lymph nodes[13]. Other symptoms include loss of appetite or unintentional weight loss (30%), upper gastrointestinal bleeding (26%), and fever or jaundice (8%)[8,14]. In the published literature, Merali et al[9] reported a case of primary duodenal tuberculosis caused by chronic peptic ulcer with the patient having normal immune function, while Kalpande et al[15] reported a case of gastric outlet obstruction.

There is also no specific radiologic feature in duodenal tuberculosis. Many studies have shown that barium meal follow-through is the most commonly used diagnostic examination, by which 80%-90% of cases show intestinal lesions, such as multiple stenosis and cecal dilatation or terminal ileum[16-18]. In upper abdominal CT, thickening of the duodenal wall associated with lymph node enlargement is often visible, which may be a clue to diagnosis[8]. However, the observed thickening of the duodenal wall still needs to be differentiated from a duodenal tumor, as in this case, and further pathological diagnosis is needed to avoid misdiagnosis.

In our case, the patient presented with epigastric pain and was initially diagnosed with a malignant tumor by abdominal CT examination. The endoscopic examination revealed a hyperemic irregular mass of the duodenum, without passage disturbance. According to a review, endoscopic findings may reveal features of gastrointestinal tuberculosis, including the morphological characters of ulcerative, ulcerohypertrophic, and hypertrophic forms. The least common form among these is hypertrophic (approximately 10%), and it is characterized by scarring, fibrosis, and pseudotumor formation[19,20]. In general, however, all forms appear as an inflammatory mass with an ulcerated and thickened mucosa.

The most convenient method for endoscopic evaluation is multiple-specimen biopsy, which should be sent for histological analysis, AFB staining/culture, and polymerase chain reaction testing[21]. Ideally, a mucosal biopsy sample taken during endoscopy would show aflatoxin or caseous necrosis to diagnose intestinal tuberculosis. However, the prevalence of these findings is low. If the endoscopic biopsy is superficial, the histology of typical caseous granuloma may not be seen, because the granuloma of intestinal tuberculosis may be located in the submucosa, highlighting the importance of multiple deep biopsies to improve diagnostic efficiency. The evidence of AFB and granulomatous inflammation may be a clue for diagnosis. However, only about 30% of gastrointestinal cases show positivity of specific cytological and histopathological findings[22]. It has also been reported that the histological finding (i.e. from AFB staining) of caseoid necrosis in endoscopic biopsy specimens only slightly increased the sensitivity for detection of intestinal tuberculosis. In a retrospective study in Korea[21], the sensitivities of caseoid necrosis and AFB positivity were only 11.1% and 17.3%, respectively. Of the 225 patients who were eventually diagnosed with intestinal tuberculosis in that study, only 23.1% had one of the manifestations (caseoid necrosis or AFB-positive) to diagnose intestinal tuberculosis, while the addition of mycobacterium culture increased the sensitivity to 38.7%. Although the sensitivity of AFB staining is low, it is still considered a clinically useful auxiliary method due to its high specificity, and it should remain an important part of the diagnostic evaluation of endoscopic biopsy specimens[21].

Duodenal tuberculosis without serious complications is mainly treated by internal medicine, while a duodenal tumor necessitates surgical treatment. As duodenal tuberculosis is easily misdiagnosed, many cases may be clearly diagnosed by postoperative pathology, but this also brings additional (unnecessary) trauma to patients. Generally, the recommended treatment for abdominal tuberculosis is anti-tuberculosis treatment[3]. The most current tuberculosis treatment regimens use multi-drug combinations, ranging from 6 mo for drug-sensitive tuberculosis patients to 9-20 mo for drug-resistant tuberculosis patients or longer when new drug resistance develops during the treatment. Surgical intervention may also be required to establish the diagnosis if medical treatment fails or to treat complications of abdominal tuberculosis[20].

Globally, the most recent available data (published in a 2019 tuberculosis report) show an 85% success rate for drug-sensitive tuberculosis, 56% for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, and only 39% for extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. Among the new drugs developed in 2019, there are 13 new compounds, seven of which belong to a new chemical class; these are the DprE1 inhibitor btz-043, new azole compound gsk-3036656, macozinone, quinolone derivative opc-167832, imidazolidine Q203, oral antibiotic SPR720, and DprE1 enzyme inhibitor tba-7371. Three other drugs (bedecurine, deramanide, and putomanide) have been approved. Further testing is under way on seven recycled drugs, including clofazimine, linezolid, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, nidazonide, rifampicin (in high doses), and rifapentine[1]. In tuberculosis vaccine research, a total of 14 kinds of new vaccines are currently in phase I, II, or III clinical trials, with three being in phase I and 11 being in phase II or phase III clinical trials. This also includes two that were introduced in trial within the past year[2,4]. The tuberculosis vaccine (M72/AS01E) II b stage trial found a significant reduction in the incidence of tuberculosis in adults with latent tuberculosis infection and negativity for human immunodeficiency virus, highlighting its potential as a great breakthrough in this field[1]. Although much progress has been made in tuberculosis research, the global incidence situation is still grim, and increasing the detection rate of tuberculosis in rare sites will undoubtedly benefit the management of future cases.

In short, primary duodenal tuberculosis is a rare disease of the gastrointestinal tract, which cannot be ignored in the differential diagnosis of duodenal ulcer, hyperplasia, tumor, and other diseases. Due to the lack of specificity, when radiology cannot make a definite diagnosis, multiple standard endoscopic histopathological biopsies and tuberculosis-related examinations can be used to improve the diagnostic accuracy. If there are no surgical indications, such as duodenal obstruction, duodenal tuberculosis can be diagnosed and treated with internal medicine earlier, so that unnecessary surgical procedures can be avoided.

The treatment of tuberculosis is a worldwide problem, and the diagnosis of tuberculosis in rare sites remains a challenge. The incidence of gastrointestinal tuberculosis is relatively low, while primary duodenal tuberculosis is more rare. Although it has been reported in the literature, it is still easy to be misdiagnosed as ulcer, tumor, and inflammatory bowel disease. Wrong diagnosis often leads to wrong treatment or serious complications due to delayed treatment. Therefore, it is of great significance for patients that differential diagnosis be made through optimized imaging and histological analyses, in conjunction with related specialist examination. Early medical drug treatment can reduce the occurrence of serious complications and avoid unnecessary surgery.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Zavras N S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/2019.12.17. |

| 2. | Chaudhary P, Khan AQ, Lal R, Bhadana U. Gastric tuberculosis. Indian J Tuberc. 2019;66:411-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Shreshtha S, Ghuliani D. Abdominal tuberculosis: A retrospective analysis of 45 cases. Indian J Tuberc. 2016;63:219-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Agrawal S, Shetty SV, Bakshi G. Primary hypertrophic tuberculosis of the pyloroduodenal area: report of 2 cases. J Postgrad Med. 1999;45:10-12. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Upadhyaya VD, Kumar B, Lal R, Sharma MS, Singh M, Rudramani. Primary duodenal tuberculosis presenting as gastric-outlet obstruction: Its diagnosis. Afr J Paediatr Surg. 2013;10:83-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rao YG, Pande GK, Sahni P, Chattopadhyay TK. Gastroduodenal tuberculosis management guidelines, based on a large experience and a review of the literature. Can J Surg. 2004;47:364-368. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Negi SS, Sachdev AK, Chaudhary A, Kumar N, Gondal R. Surgical management of obstructive gastroduodenal tuberculosis. Trop Gastroenterol. 2003;24:39-41. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Rehman A, Saeed A, Jamil K, Zaidi A, Azeem Q, Abdullah K, Rustam T, Qureshi N, Akram M. Hypertrophic pyloroduodenal tuberculosis. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2008;18:509-511. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Merali N, Chandak P, Doddi S, Sinha P. Non-healing gastro-duodenal ulcer: A rare presentation of primary abdominal tuberculosis. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;6C:8-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kaushik SP, Bassett ML, McDonald C, Lin BP, Bokey EL. Case report: gastrointestinal tuberculosis simulating Crohn's disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;11:532-534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jung JH, Kim SH, Kim MJ, Cho YK, Ahn SB, Son BK, Jo YJ, Park YS. A case report of primary duodenal tuberculosis mimicking a malignant tumor. Clin Endosc. 2014;47:346-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sharma BC, Prasad H, Bhasin DK, Singh K. Gastroduodenal tuberculosis presenting with massive hematemesis in a pregnant woman. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;30:336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chang A, Chantarojanasiri T, Pausawasdi N. Duodenal tuberculosis; uncommon cause of gastric outlet obstruction. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2020;13:198-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lamberty G, Pappalardo E, Dresse D, Denoël A. Primary duodenal tuberculosis: a case report. Acta Chir Belg. 2008;108:590-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kalpande S, Pandya JS, Tiwari A, Adhikari D. Gastric outlet obstruction: an unusual case of primary duodenal tuberculosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bhargava DK. Abdominal Tuberculosis: Current Status. Apollo Med. 2007;4:287-291. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Uygur-Bayramicli O, Dabak G, Dabak R. A clinical dilemma: abdominal tuberculosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:1098-1101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chong VH. Differences in patient profiles of abdominal and pulmonary tuberculosis: a comparative study. Med J Malaysia. 2011;66:318-321. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Sharma MP, Bhatia V. Abdominal tuberculosis. Indian J Med Res. 2004;120:305-315. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Lazarus AA, Thilagar B. Abdominal tuberculosis. Dis Mon. 2007;53:32-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Choi EH, Coyle WJ. Gastrointestinal Tuberculosis. Microbiol Spectr. 2016;4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kim YS, Kim YH, Lee KM, Kim JS, Park YS; IBD Study Group of the Korean Association of the Study of Intestinal Diseases. [Diagnostic guideline of intestinal tuberculosis]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2009;53:177-186. [PubMed] |