Published online Dec 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i24.6529

Peer-review started: September 25, 2020

First decision: October 18, 2020

Revised: October 22, 2020

Accepted: November 2, 2020

Article in press: November 2, 2020

Published online: December 26, 2020

Processing time: 83 Days and 9.8 Hours

Infectious common femoral artery pseudoaneurysm caused by Klebsiella pulmonary infection is a relatively infrequent entity but is potentially life and limb threatening. The management of infectious pseudoaneurysm remains controversial.

We reported a 79-year-old man with previous Klebsiella pneumoniae pulmonary infection and multiple comorbidities who presented with a progressive pulsate mass at the right groin and with right lower limb pain. Computed tomography angiography showed a 6 cm × 6 cm × 9 cm pseudoaneurysm of the right common femoral artery accompanied by occlusion of the right superficial femoral artery and deep femoral artery. He underwent endovascular treatment (EVT) with stent–graft, and etiology of infectious pseudoaneurysm was confirmed. Then, 3-mo antibiotic therapy was given. One-year follow-up showed the stent–graft was patent and complete removal of surrounding hematoma.

The femoral artery pseudoaneurysm can be caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae deriving from the pulmonary infection. Moreover, this unusual case highlights the use of EVT and prolonged antibiotic therapy for infectious pseudoaneurysm.

Core Tip: Infectious pseudoaneurysm of the femoral artery is a rare entity that is potentially life and limb threatening. Common femoral artery (CFA) pseudoaneurysm caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae has not been reported. We reported a rare infectious CFA pseudoaneurysm, which was caused by previous pulmonary infection of Klebsiella pneumoniae. After endovascular treatment (EVT) and long-term antibiotic therapy, the patient had a good result at the 1-year follow-up. This case demonstrates common femoral artery pseudoaneurysm can be caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae deriving from the pulmonary infection. Moreover, it highlights the use of EVT and prolonged antibiotic therapy for infectious pseudoaneurysm.

- Citation: Wang TH, Zhao JC, Huang B, Wang JR, Yuan D. Successful endovascular treatment with long-term antibiotic therapy for infectious pseudoaneurysm due to Klebsiella pneumoniae: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(24): 6529-6536

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i24/6529.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i24.6529

Infectious pseudoaneurysm of the femoral artery, accounting for merely 0.8% of all mycotic aneurysms, is rare and potentially life threatening[1,2]. It may be caused either by direct invasion or less commonly by the hematogenous spread of infectious organisms to the vessel wall[3]. Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus species are the most common causative pathogens[4]. Excision, debridement, and surgical reconstruction of the blood vessels are considered the standard strategy in these cases[5]. However, the clinical conditions of these patients are often critical due to both acute illness and severe infective comorbidities. The management of infectious femoral artery pseudoaneurysm remains a challenge[1-3,6]. Here, we reported a rare case of common femoral artery (CFA) pseudoaneurysm due to Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae) pulmonary infection, presenting with acute limb ischemia. The patient was successfully treated with endovascular treatment (EVT) and long-term antibiotic therapy.

A 79-year-old man presented to our emergency department with a sudden progressive mass that occurred at the right groin and with progressive right lower limb pain.

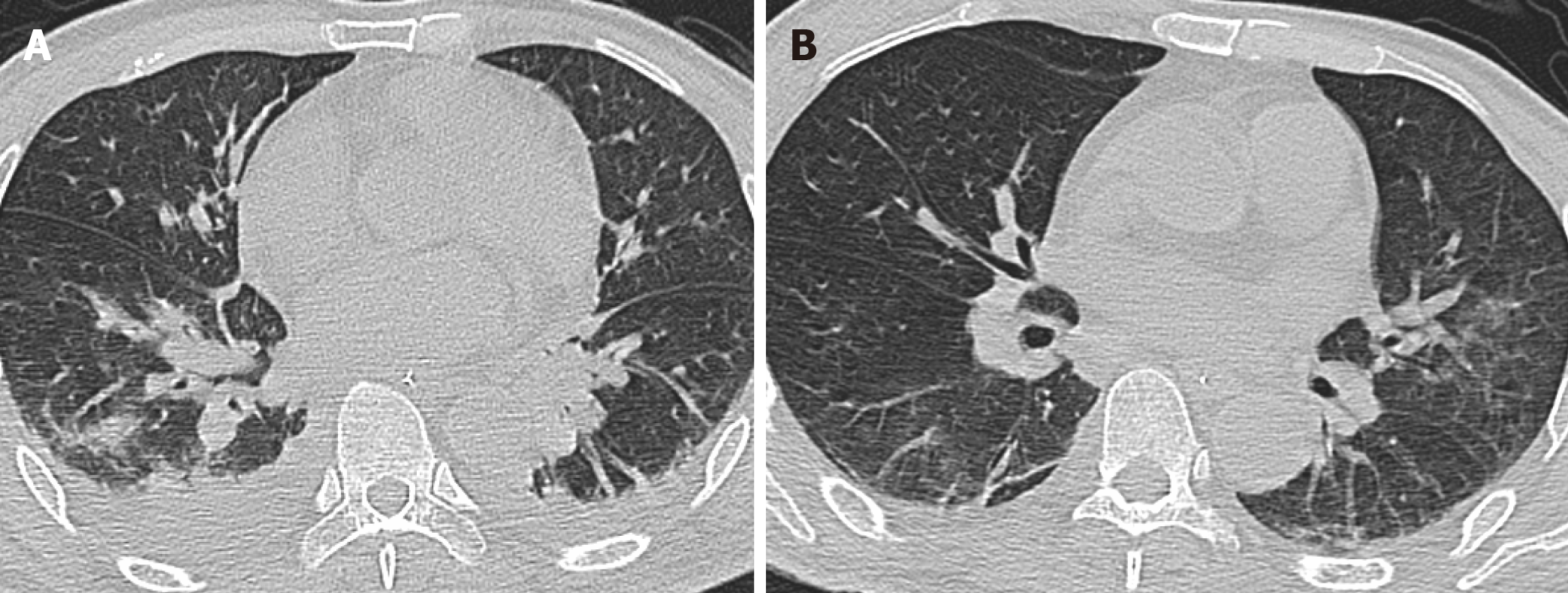

The patient, initially presenting with fever, chills, and dyspnea, was admitted to a local hospital about 1 mo ago. A chest computed tomography showed pulmonary infection (Figure 1A), and K. pneumoniae was isolated from the blood and sputum culture, which was most sensitive to ceftriaxone. No pulsate mass was noted in either groin region, and all his lower limb pulses were present. After intravenous ceftriaxone (2 g every 12 h) was administered for 7 d, his symptoms rapidly alleviated, and he was discharged. Two weeks after discharging from the local hospital, without any history of trauma, a progressive mass suddenly occurred at his right groin accompanied by right lower limb pain. Ultrasound in a local hospital showed femoral artery pseudoaneurysm, and he was transferred to our institution immediately.

This patient had a history of alcoholism, was a heavy smoker, and had poorly controlled diabetes mellitus (DM) and hypertension.

Unremarkable.

Upon admission, he had a temperature of 39.0 ºC, heart rate of 117/min, blood pressure of 165/95 mmHg, and respiratory rate of 27/min. Physical examination showed a pulsate mass at his right groin accompanied by cyanosis of the right lower limb. All pulses of the right lower limb disappeared, and tenderness of the right calf was detected.

The laboratory test yielded a blood leukocyte count of 18.7 × 109/L, C-reactive protein of 186 mg/L, procalcitonin of 0.62 ng/mL, myoglobin of 2300 ng/mL, blood glucose of 16.5 mmol/L, glycated hemoglobin of 9.2%, blood PO2 of 55 mmHg, and blood PCO2 of 50 mmHg. Repeat blood and sputum cultures were noncontributory. During EVT, partial hematoma within the pseudoaneurysm was extracted through a catheter for microbial culture, and K. pneumoniae was isolated, which was most sensitive to ceftazidime and levofloxacin (Table 1).

| Antibiotics | Result | Sensitivity | Method | Breakpoint | |

| S | R | ||||

| Ampicillin | ≥ 32 | R | MIC | ≤ 8 | ≥ 32 |

| Ampicillin/sulbactam | ≥ 32 | R | MIC | ≤ 8 | ≥ 32 |

| Ticarcillin | ≥ 128 | R | MIC | ≤ 16 | ≥ 128 |

| Ticacillin/clavulanic acid | ≥ 128 | R | MIC | ≤ 16 | ≥ 128 |

| Piperacillin | ≥ 128 | R | MIC | ≤ 16 | ≥ 128 |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | ≥ 128 | R | MIC | ≤ 16 | ≥ 128 |

| Cefuroxime | ≥ 64 | R | MIC | ≤ 8 | ≥ 32 |

| Cefazolin | ≥ 64 | R | MIC | ≤ 2 | ≥ 8 |

| Cefalotin | ≥ 64 | R | MIC | ≤ 8 | ≥ 32 |

| Ceftazidime | 1 | S | MIC | ≤ 4 | ≥ 16 |

| Ceftazidime/avibatan | 21 | S | K-B | ≥ 21 | ≤ 20 |

| Cefotaxime | ≥ 64 | R | MIC | ≤ 1 | ≥ 4 |

| Ceftriaxone | ≥ 64 | R | MIC | ≤ 1 | ≥ 4 |

| Cefepime | ≥ 64 | R | MIC | ≤ 2 | ≥ 16 |

| Cefpodoxime | ≥ 8 | R | MIC | ≤ 2 | ≥ 8 |

| Aztreonam | ≥ 64 | R | MIC | ≤ 4 | ≥ 16 |

| Meropenem | ≥ 16 | R | MIC | ≤ 1 | ≥ 4 |

| Imipenem | ≥ 16 | R | MIC | ≤ 1 | ≥ 4 |

| Gentamicin | ≥ 16 | R | MIC | ≤ 4 | ≥ 16 |

| Amikacin | ≥ 64 | R | MIC | ≤ 16 | ≥ 64 |

| Ciprofloxacin | ≥ 2 | R | MIC | ≤ 0.25 | ≥ 1 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.25 | S | MIC | ≤ 0.5 | ≥ 2 |

| Moxifloxacin | 1 | S | MIC | ≤ 1 | ≥ 4 |

| Cotrimoxazole | ≥ 16 | R | MIC | ≤ 2 | ≥ 4 |

| Polymyxin B | 1 | S | MIC | ≤ 1 | ≥ 4 |

| Tetracycline | 4 | S | MIC | ≤ 4 | ≥ 16 |

| Tigecycline | 2 | S | MIC | ≤ 2 | ≥ 8 |

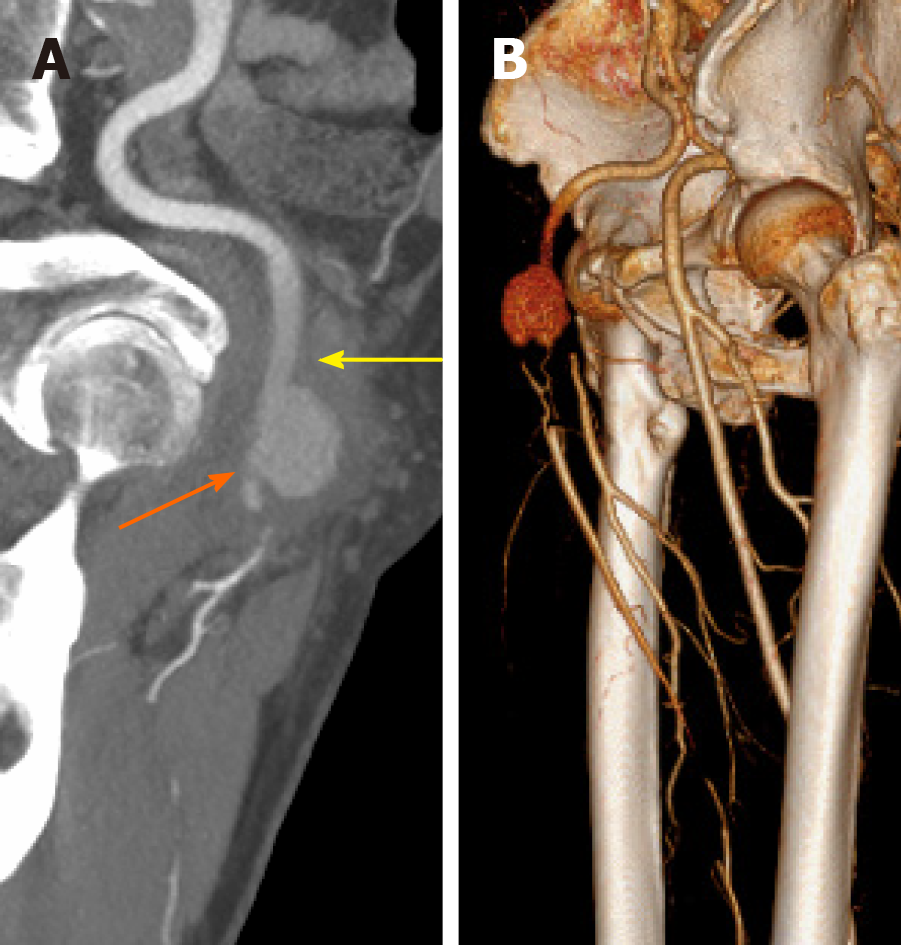

The chest computed tomography showed that the pulmonary infection had significantly improved; however, inflammatory infiltration of both lungs was still present (Figure 1B). Computed tomography angiography (CTA) showed a 6 cm × 6 cm × 9 cm pseudoaneurysm of the right CFA accompanied by occlusion of the right superficial femoral artery (SFA) and deep femoral artery (DFA) (Figure 2). The echocardiogram was unremarkable.

The final diagnosis of the presented case is spontaneous CFA pseudoaneurysm due to K. pneumoniae accompanied by multiple comorbidities.

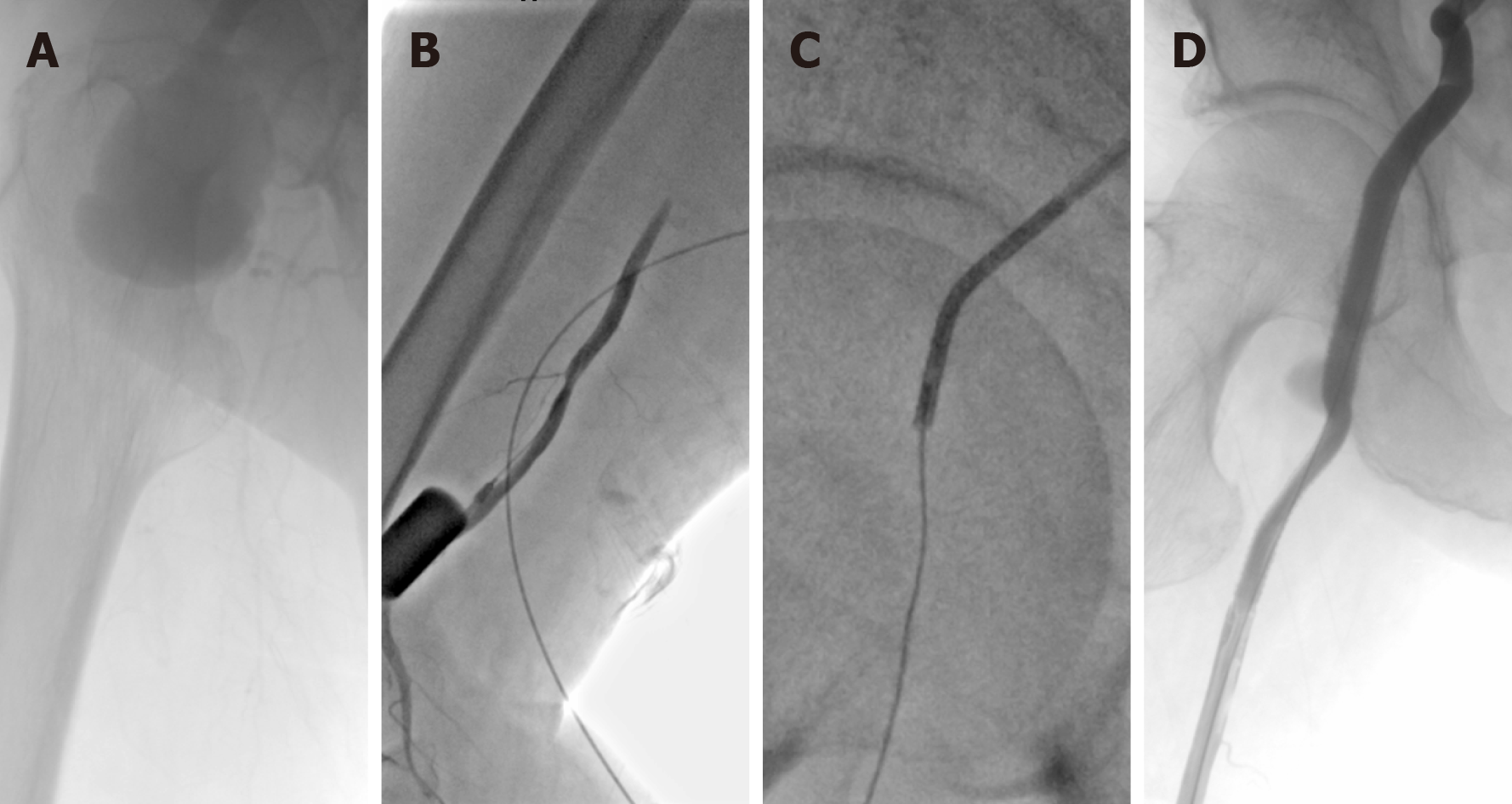

Considering the multiple cardiorespiratory comorbidities of this patient, an open surgical repair (OSR) was not suitable. Because the CFA pseudoaneurysm was accompanied by severe lower limb ischemia, an emergency EVT with local anesthesia was performed. Left femoral access was achieved using a pre-close technique (ProGlide; Abbott Vascular, United States). Intraoperative angiography showed pseudoaneurysm of the CFA and occlusion of the SFA and DFA (Figure 3A). A little hematoma within the pseudoaneurysm was extracted through a catheter for microbial culture. Unfortunately, the compression caused by the pseudoaneurysm prevented the guidewires from passing through the occlusion lesion. Thus, retrograde access was achieved at the distal part of the SFA, and a V-18 control guidewire (Boston Scientific) was passed through the occlusion lesion into the proximal CFA. Then, this guidewire was manipulated into the antegrade catheter (Figure 3B and 3C). After the pathway was established, two Viabahn (Gore, Flagstaff, United States) stent–grafts (8 mm × 100 mm and 8 mm × 50 mm) were deployed. Final angiography showed that the stent–grafts and distal SFA were patent without any endoleaks (Figure 3D).

When the patient was transferred to our hospital, empirical antibiotic therapy with intravenous ceftriaxone (2 g every 12 h) was given for suspicious infectious pseudoaneurysm. Then, the antibiotic was switched to intravenous ceftazidime (2 g every 8 h) according to the microbial culture of the hematoma in the pseudoaneurysm. After 14 d of antibiotic therapy with intravenous ceftazidime, this patient was discharged, and antibiotics were switched to oral levofloxacin (0.5 g/d) for 3 mo.

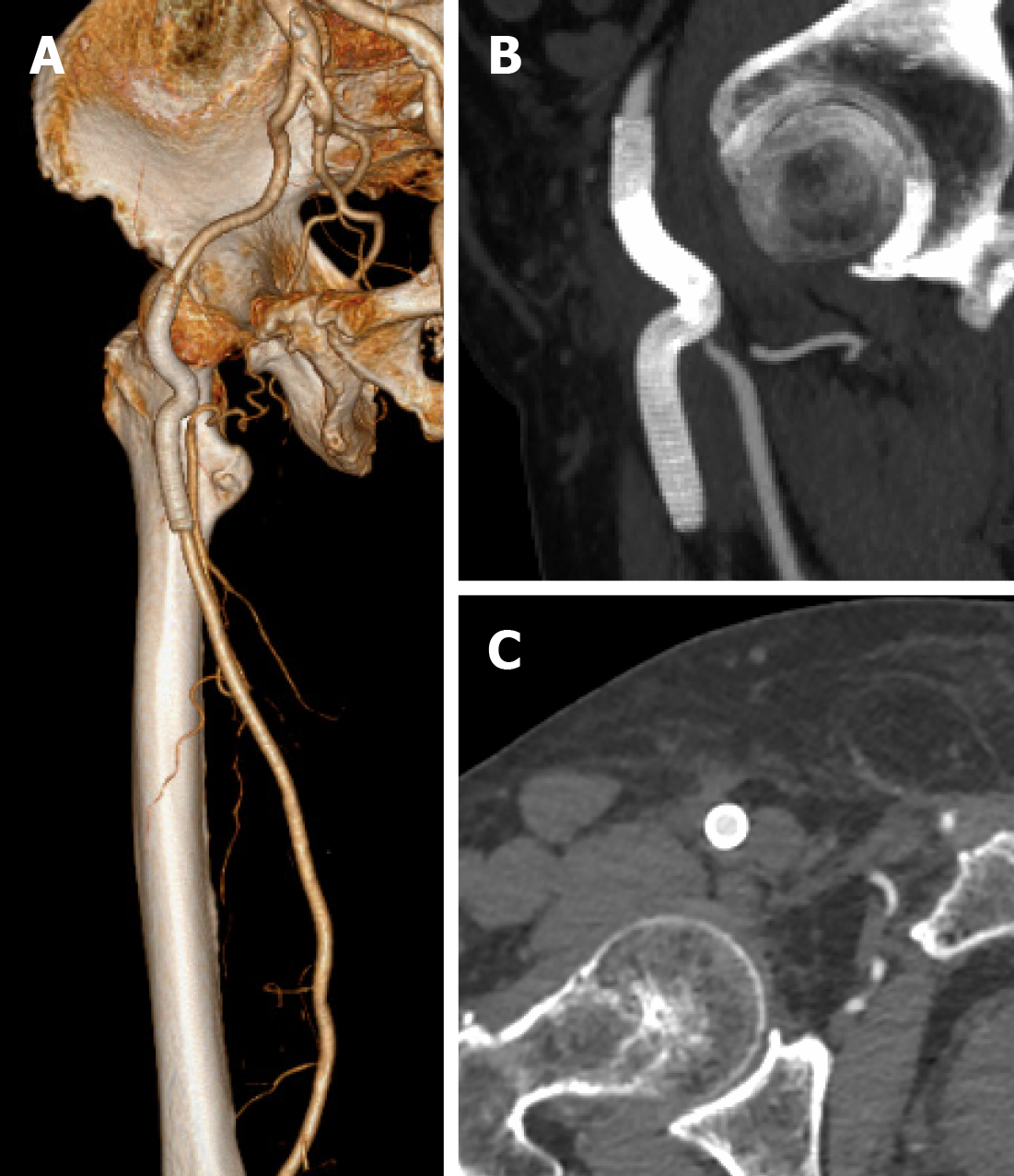

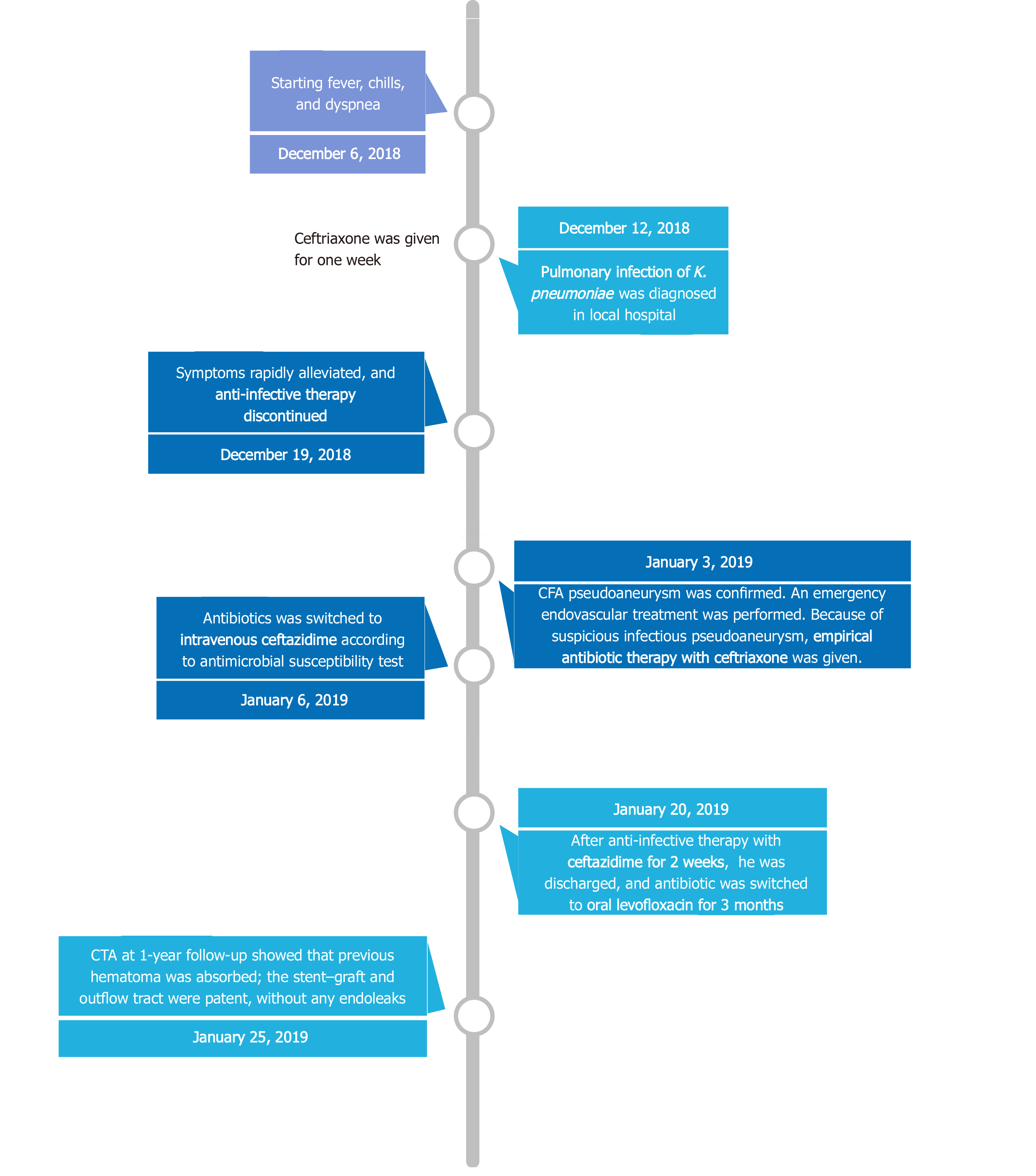

The postoperative course was uneventful. Bilateral dorsalis pedis could be palpated. Repeat blood cultures were negative, and no complications occurred. One month after hospital discharge, the inguinal mass disappeared. CTA at the 1-year follow-up showed that the previous hematoma was absorbed; the stent–graft and outflow tract were patent without any endoleaks (Figure 4). The timeline of the patient’s treatment is outlined in Figure 5.

Infectious pseudoaneurysms are characterized by the destruction of the artery wall via an infectious process and are associated with significant morbidity and mortality[1,2]. The etiology of infectious pseudoaneurysm has been changing with septic emboli of endocarditis being the most common cause of arterial trauma in the post-antibiotic period. The less common cause is circulating organisms directly infecting the arterial walls as in cases of bacteremia. The risk factors for infectious pseudoaneurysm include underlying arterial pathologies, such as atherosclerotic disease and endothelial cell dysfunction[3,7,8]. These factors can disrupt the integrity of the vessel wall; moreover, they will hasten the destruction of the intima and media layers by infectious organisms[4]. Potential predisposing conditions include malignancy, DM, an immune-compromised state, and severe comorbidities[3]. Although infectious pseudoaneurysm caused by bacteremia is a rare entity, a few authors had reported aortic pseudoaneurysm caused by pulmonary infection[9]. The infected sites varied considerably. Because of hemodynamics, the arterial bifurcation may be invaded by circulating organisms[8]. Therefore, CFA can be affected by circulating organisms during bacteremia in certain cases.

Numerous organisms, including Staphylococcus aureus (30% of all cases), other Streptococcus species (14%), and Salmonella (10%), may cause infectious pseudoaneurysms[8]. K. pneumoniae is a normal flora of the human mouth and intestine. The various clinical manifestations of K. pneumoniae include pneumonia, intra-abdominal infection, bacteremia, and soft tissue infection[9,10]. However, pseudoa-neurysm caused by K. pneumoniae is rare. DM is the most common risk factor in K. pneumoniae pseudoaneurysm, which exists in most reported cases[3]. Some authors reported K. pneumoniae-associated thoracic or abdominal aortic pseudoaneurysm but not K. pneumoniae-associated femoral artery pseudoaneurysm[9,11]. In our case, the patient had a history of bacteremia caused by K. pneumoniae pneumonia accompanied by DM, atherosclerosis, and multiple severe comorbidities. Moreover, K. pneumoniae was isolated from the hematoma within the pseudoaneurysm. All evidence demonstrated that this CFA pseudoaneurysm was caused by K. pneumoniae derived from the pulmonary infection.

Treatment of infectious pseudoaneurysm is a perpetual challenge[2]. OSR requires radical debridement with excision of all the infected arterial segments and surrounding tissues, followed by ligation of the affected artery or revascularization with synthetic or autologous graft[12]. Given the possibility of severe limb ischemia with ligation alone, revascularization is universally accepted as the foundation of treatment[5]. However, in situ reconstruction with synthetic or autologous graft leaves the patient susceptible to infection of the new graft, while the extra-anatomic reconstruction requires complex operations to restore the natural direction of blood flow[2]. Moreover, hemorrhage-associated complications caused by OSR and the invasive approach may increase the likelihood of mortality. Compared with OSR, exclusion with covered stent–graft is a minimally invasive procedure[1,6]. Obviously, a case for EVT for a high-risk surgical candidate with a CFA pseudoaneurysm could be made[8]. Our patient had multiple severe comorbidities and was in a poor general condition. Therefore, EVT was a reasonable choice for this patient.

Endovascular exclusion of the infectious CFA pseudoaneurysm has been described, especially in patients not fit for a risky OSR or as a bridge therapy until definitive surgery[4,5,12]. However, placement of a stent–graft into an infected environment is not appropriate. EVT of infectious pseudoaneurysm has shown complications of 20.0% and early mortality of 5.5%, which are higher than the incidence of complications and early mortality associated with OSR[2]. The management of the DFA is also a challenge for CFA pseudoaneurysm in bifurcated lesions as it may cause persistent bleeding for retrograde perfusion from the DFA. Some authors described coil embolization of the DFA, and although technically feasible, it increases the possibility of subsequent abscess formation[2]. Fortunately, the original part of the DFA of this patient had already occluded, which did not require additional dispose for the DFA. Moreover, the compression of the pseudoaneurysm may cause distal outflow tract distortion and occlusion, which make EVT challenging. The retrograde access can assist in establishing the pathway of EVT. This technique has been widely used in peripheral artery diseases and can also be a reasonable choice for EVT in CFA pseudoaneurysm with distal artery occlusion[12,13].

Empirical antibiotics should be initiated immediately after the diagnosis of infectious pseudoaneurysm. Subsequently, the antibiotics should be changed according to the results of susceptibility testing[3,6]. Microbiological diagnosis is crucial as a guide in the management of the condition. The specimen of a pseudoaneurysm is difficult to obtain during EVT, which may make the etiology diagnosis difficult[4]. In our case, we extracted the blood from the pseudoaneurysm for microbial culture. This method is feasible for determining the specific organism involved in infectious pseudoaneurysm.

The period of antibiotic therapy is controversial[9]. A 2-wk treatment course for primary K. pneumoniae bacteremia would be optimal. The antibiotic course of our patient was inadequate in his first pulmonary infection, which resulted in infectious CFA pseudoaneurysm. During the second episode of K. pneumoniae infection, a longer antibiotic course was recommended. Moreover, the persistence of an organism after EVT of infectious pseudoaneurysm requires prolonged antibiotic therapy as a stent–graft is used. Some reports indicated that at least 2 wk of intravenous antimicrobial therapy was needed, followed by administration of oral antibiotics for 6 wk or longer for patients undergoing EVT for infectious pseudoaneurysm[3,5,6]. Our patient had a good long-term result with subsequent prolonged and continued antibiotic therapy after EVT.

Infectious CFA pseudoaneurysm caused by K. pneumoniae pulmonary infection is a rare clinical entity and is usually associated with multiple comorbidities. Our case demonstrates an endovascular solution to this challenging and lethal disease process as a suitable alternative to traditional OSR. Prompt pathogen diagnosis and continued antibiotic therapy are also crucial in patients with infectious pseudoaneurysm undergoing EVT.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Peripheral vascular disease

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Tanabe H S-Editor: Liu M L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Xu J, Zheng Z, Yang Y, Zhang W, Zhao H, E B, Zheng M. Clinical evaluation of covered stents in the treatment of superficial femoral artery pseudoaneurysm in drug abusers. Mol Med Rep. 2018;17:4460-4466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Inaraja-Pérez GC, Adoración RC, Jose-Antonio LS, Maria-Isabel LG, Irene SV. A Bail Out Solution for an Urgent Situation: Endovascular Exclusion and Embolization of an Infected Femoral Pseudoaneurysm. Ann Vasc Surg. 2020;69:454.e1-454.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hussain M, Roche-Nagle G. Infected pseudoaneurysm of the superficial femoral artery in a patient with Salmonella enteritidis bacteremia. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2013;24:e24-e25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gooneratne TD, Sriskantha S, Wijeyaratne M. A case of a mycotic aneurysm of the superficial femoral artery infected by mixed bacterial species. Ann Vasc Dis. 2011;4:325-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Li K, Beckerman WE, Luo X, Peng HW, Chen KQ, He CG. Graft Infection after Prosthetic Bypass Surgery for Infectious Femoral Artery Pseudoaneurysm in Intravenous Drug Users: Manifestation, Management, and Prognosis. Ann Vasc Surg. 2020 epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wooster MD, Shames ML. Mycotic pseudoaneurysm of a superficial femoral artery stent. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2013;47:470-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kocovski L, Butany J, Nair V. Femoral artery pseudoaneurysm due to Candida albicans in an injection drug user. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2014;23:50-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bowden DJ, Hayes PD, Sadat U, Choon See T. Mycotic pseudoaneurysm of the superficial femoral artery in a patient with Cushing disease: case report and literature review. Vascular. 2009;17:163-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chuang YC, Lee MF, Yu WL. Mycotic aneurysm caused by hypermucoviscous Klebsiella pneumoniae serotype K54 with sequence type 29: an emerging threat. Infection. 2013;41:1041-1044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chao CM, Lee KK, Wang CS, Chen PJ, Yeh TC. A Fatal Case of Klebsiella pneumoniae Mycotic Aneurysm. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2011;2011:498545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chen X, Yuan D, Zhao J, Huang B, Yang Y. Hybrid repair for a complex infection aortic pseudoaneurysm with continued antibiotic therapy: A case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e14330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mehta T, Dey R, Chaudhuri A. Ilioprofunda Endobypass Can Successfully Treat a Post-Operative Femoral Pseudo-Aneurysm. EJVES Short Rep. 2017;34:9-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zhuang KD, Tan SG, Tay KH. The "SAFARI" technique using retrograde access via peroneal artery access. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2012;35:927-931. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |