Published online Dec 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i24.6504

Peer-review started: September 20, 2020

First decision: September 29, 2020

Revised: October 14, 2020

Accepted: November 2, 2020

Article in press: November 2, 2020

Published online: December 26, 2020

Processing time: 90 Days and 12.9 Hours

Trocar site hernia (TSH) is a rare but potentially dangerous complication of laparoscopic surgery, and the drain-site TSH is an even rarer type. Due to the difficulty to diagnose at early stages, TSH often leads to a delay in surgical intervention and eventually results in life-threatening consequences. Herein, we report an unusual case of drain-site TSH, followed by a brief literature review. Finally, we provide a novel, simple, and practical method of prevention.

A 54-year-old female patient underwent laparoscopic subtotal hysterectomy and bilateral adnexectomy for uterine fibroids 8 d ago in another hospital. She was admitted to our hospital with a 2-d history of intermittent abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal enlargement with an inability to pass stool and flatus. The emergency computed tomography scan revealed the small bowel herniated through a 10 mm trocar incision, which was used as a drainage port, with diffuse bowel distension and multiple air-fluid levels with gas in the small intestines. She was diagnosed with drain-site strangulated TSH. The emergency exploratory laparotomy confirmed the diagnosis. A herniorrhaphy followed by standard intestinal resection and anastomosis were performed. The patient recovered well after the operation and was discharged on postoperative day 8 and had no postoperative complications at her 2-wk follow-up visit.

TSH must be kept in mind during the differential diagnosis of post-laparoscopic obstruction, especially after the removal of the drainage tube, to avoid the serious consequences caused by delayed diagnosis. Furthermore, all abdomen layers should be carefully closed under direct vision at the trocar port site, especially where the drainage tube was placed. Our simple and practical method of prevention may be a novel strategy worthy of clinical promotion.

Core Tip: Trocar site hernia (TSH) is a rare but potentially dangerous complication of laparoscopic surgery, and drain-site TSH is an even rarer type. In clinical practice, fascial-muscular and peritoneal defects at the drain-site are often left open to allow the drain to pass through, which facilitates the formation of a drain-site TSH. We present a rare case of a drain-site strangulated TSH at the lateral 10 mm port site soon after the removal of the intraperitoneal drainage tube following laparoscopic subtotal hysterectomy and bilateral adnexectomy. Finally, we provide a new, practical, and simple method of prevention.

- Citation: Gao X, Chen Q, Wang C, Yu YY, Yang L, Zhou ZG. Rare case of drain-site hernia after laparoscopic surgery and a novel strategy of prevention: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(24): 6504-6510

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i24/6504.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i24.6504

Trocar site hernia (TSH) is a rare but potentially dangerous complication of minimally invasive surgery, often leading to life-threatening consequences. The incidence for adults has been reported to range from 0%-5.2% and continues to increase with the rise in the adoption of laparoscopic procedures[1]. Most of these hernias are reported to be associated with ≥ 10 mm trocars at the umbilical port site, although few studies have reported TSHs with varying port sizes or other locations[1-4]. Among TSHs, drain-site hernias represent a special type that occurs at the port site where the drainage tube is placed. In clinical practice, fascial-muscular and peritoneal defects at the drain-site are often left open to allow the drain to pass through, which facilitates the formation of a drain-site TSH. Few cases of drain-site TSHs have been reported previously, while the optimal approach to close drain-site trocar incision is still unclear, leading to the occurrence of TSH occasionally and resulting in disastrous consequence[5-7].

We report a rare case of drain-site strangulated TSH at a lateral 10 mm port site soon after the removal of intraperitoneal drains following laparoscopic surgery with the hope of enhancing the general understanding of such cases. Furthermore, we provide a novel, simple, and practical method of prevention.

A 54-year-old obese female (body mass index, 28.4 kg/m2) presented to the Emergency Department of the West China Hospital with a 2-d history of intermittent abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal enlargement with an inability to pass stool and flatus.

She had undergone laparoscopic subtotal hysterectomy and bilateral adnexectomy in another institution 8 d prior because of uterine fibroids. During the operation, three trocars were applied: Two 10 mm trocars at the umbilicus and in the left lower quadrant, respectively, and a 5 mm trocar in the right lower quadrant, all of which were the bladed type. Additionally, a 24 FR soft silicon tube was drained through the 10 mm trocar port-site in the left lower quadrant. The fascial planes of the umbilical and right lower quadrant port sites were separately stitched with absorbable sutures, while the 10 mm port site in the left lower quadrant was left unclosed (only skin and subcutaneous tissue were sutured to fix the drain). The postoperative recovery was smooth, and gastrointestinal function recovered within 48 h. The drainage tube was removed 4 d after the operation under direct vision when the collected drainage liquid was less than 30 mL per day. One day later, she was discharged to home without discomfort. Six days after the operation, she felt dull pain at the site of the left drain accompanied with nausea, but she did not have difficulty passing stool or flatus. The patient thought the problem was probably due to the incision and did not pay much attention. From that day on, the abdominal pain and distension were gradually aggravated, with the onset of the inability to pass stool and flatus.

The patient had a history of uncontrolled diabetes mellitus and uterine fibroids.

The patient had no remarkable personal and family history.

The primary symptoms were a distended abdomen, strong sensitivity at the left lower quadrant with a rebound, a tender 8 cm in size palpable mass in the left lower quadrant just above the drainage site, and hyperactive bowel sounds.

All hematological parameters were within normal limits. The biochemical values were significant for Na+ (131 mmol/L), Cl- (89 mmol/L), glucose level (21.5 mmol/L), alanine aminotransferase (114 IU/L), and aspartate aminotransferase (120 IU/L).

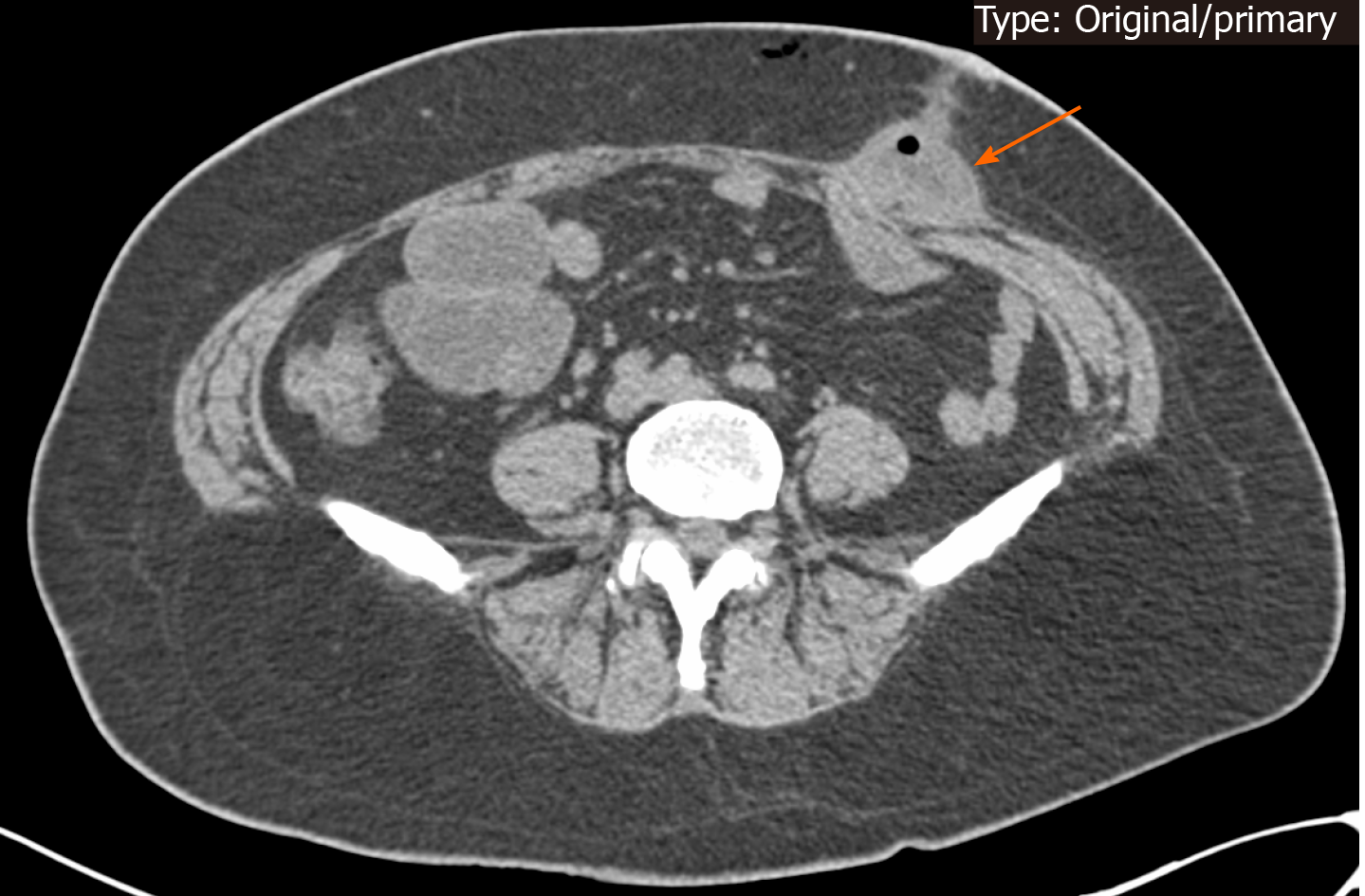

The emergency computed tomography (CT) scan revealed the small bowel herniated through the 10 mm drain-site, with diffuse bowel distension and multiple air-fluid levels with gas in the small intestines (Figure 1).

Based on her clinical presentation and radiographic findings, she was diagnosed with drain-site strangulated TSH.

The patient was taken to the operating room for emergency exploratory laparotomy. Surgery revealed the small intestine, approximately 1.5 m from the Treitz ligament, protruding into the peritoneal defect just located at the drainage site. These findings confirmed the preoperative diagnosis. The previous incision was extended laterally and gently reposted back to the strangulated intestine without causing damage. The herniated intestinal canal was approximately 5 cm in length and was necrotic; thus, the standard intestinal resection and anastomosis were performed. The fascial-muscular and peritoneal defects were carefully closed with interrupted Vicry 2/0 sutures.

She recovered well after the operation and was discharged on postoperative day 5. She had no postoperative complications at her 2-wk follow-up visit.

TSH is defined as an incisional hernia occurring at the trocar incision site after laparoscopic procedures. The first TSH was reported by Fear[8] in gynecological laparoscopy in 1968. Since then, many such cases have been reported with the increase in the adoption of laparoscopic procedures. Although TSH is rare, it is a serious complication with the potential to lead to life-threatening complications, such as bowel obstruction and strangulation, often leading to further surgery.

The common clinical presentations of TSH are nausea, vomiting, poor exhaust and defecation, abdominal pain, abdominal mass, or protuberance. The appearance of these symptoms can range from several days to several months after the operation, although they usually occur within days of surgery. According to Tonouchi et al[9] and Velasco et al[10], TSHs can be classified into three types based on the clinical presentations: The early-onset type (dehiscence of fascia and peritoneum, often presents with small bowel obstruction within 2 wk after surgery without a sac), late-onset type (dehiscence of the fascial plane, often appears without small bowel obstruction within several months after the operation with a sac consisting of peritoneum), and special type (dehiscence of the whole abdominal wall may occur at any time after surgery). If TSH is suspected, emergency ultrasonography or abdominal CT scans should be considered, especially abdominal CT scans, which can not only reveal the herniation site but also define its classification. Once TSH is confirmed, emergency explorative surgery should be considered because the relatively narrow aperture of TSH results in an extremely low probability of self-relief and eventually leads to bowel incarceration or even necrosis. In terms of the surgical options, both exploratory laparotomy and laparoscopy can be applied, without any advantage of one over the other[11,12].

The commonly recognized risk factors leading to TSH have been categorized according to their relationships with surgery and patients. The patient-related risk factors mainly include age > 60 years, poor nutrition, obesity (body mass index > 28 kg/m2), smoking, uncontrolled diabetes, previous abdominal surgery history, increased intraabdominal pressure, and incision infection. The surgery-related risk factors include the number of trocars used and their diameters, the type of trocar tip (bladed, non-bladed, or radially expanding), the insertion technique, the position of the trocar site, a longer operation time, and the method of withdrawing the trocar. Among these, the most critical factors are the size of the trocars and the trocar site position. Almost all TSHs have been reported to be associated with ≥ 10 mm trocar port sites at the umbilical port site, although sparse studies have reported hernias occurring at 5 mm or 3 mm trocar port sites or in the lateral abdominal wall. A recent systematic review by Swank et al[1] demonstrated that approximately 96% of TSHs were associated with 10/12 mm trocar sites, and most of them occur at the umbilical port site (82%). The reason why TSH often occurs at the umbilical port site is possibly due to the single fascia layer at the linea alba and the presence of the umbilicus, which creates a natural defect at this position. Regarding our case, the patient was an elderly obese woman with a history of uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, and pyramidal type 10 mm trocars were used during the operation. All of these risk factors may be responsible for the occurrence of the current hernia.

Regarding the current case, the drainage site TSH may have been facilitated by several additional risk factors, the most important of which possibly being the non-closure of the fascial planes and peritoneum. In the trocar site where the drain was placed, the fascial planes and peritoneum were often left unclosed, and only the skin and subcutaneous tissue were simply sutured to fix the drain. This forms a persistent and potential fascial defect after removing the drain, which may facilitate the TSH occurrence. Moreover, the drain itself may be another important risk factor promoting herniation because they trap or create a suction effect of the intestine when they were removed.

To our knowledge, few studies have reported drain-site TSHs. Komuta et al[13] reported a drainage site TSH that appeared at the lateral 10 mm port site after laparoscopy. Furthermore, Moreaux et al[6] showed two cases of drainage site TSHs at the 5 mm port site. Manigrasso et al[7] also presented a case of drainage site TSH at the lateral 10 mm port site where the drainage tube was still inserted. All of them reported that hernias occurred at the drainage sites where the fascial planes and peritoneum were unclosed, while none of them provided an optimal solution regarding the closure of the drain-site incision. They suggested that the drain should be set through a new incision or set at the port site smaller than 10 mm[6,13]. However, to avoid additional trauma, it is sometimes unavoidable in daily clinical practice to place a thick drain at the 10 mm or larger port site for adequate drainage.

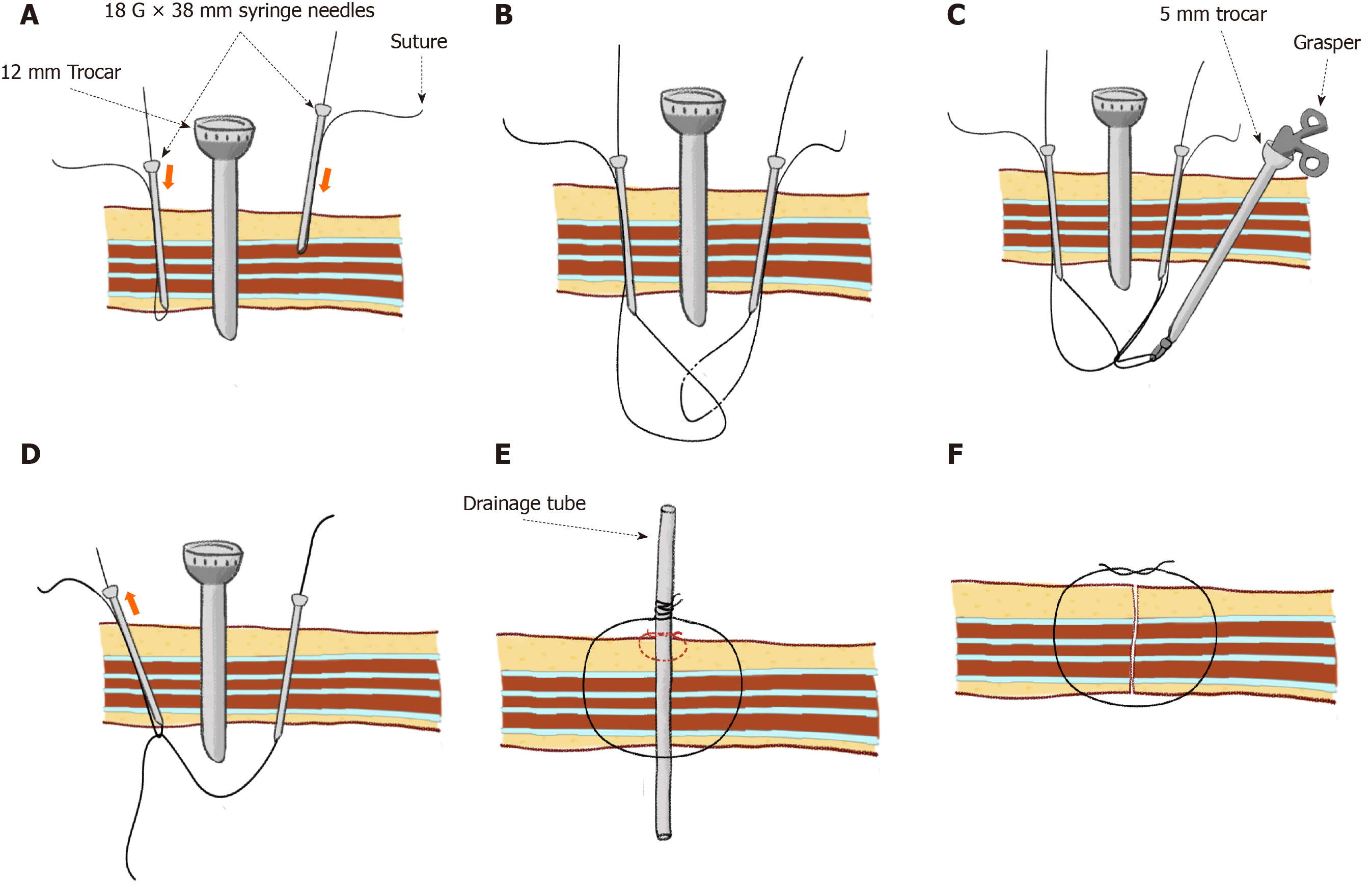

Completely closing all layers of the abdominal wall at the trocar site, especially where the drain is placed, is an important intervention to prevent TSH formation; however, the optimal approach remains unknown. The most commonly used method is blind suturing, which is difficult and time-consuming, causes potential damage to abdominal contents, and is probably impossible via the standard technique, especially in obese patients. Some surgeons also recommend the use of a fascial closure device, a suture carrier, an Endoclose suture device, a spinal cord needle, or a Deschamps needle to close the fascia and the peritoneum together. However, these methods often require special equipment that is not easily found on the operating table. In our institution, we usually pre-embed a suture by using a syringe needle (18 G × 38 mm) penetrating through the whole abdominal wall at the edges of the incision under direct vision before we withdraw the camera. This simple and practical technique enables us to close completely the incision after the removal of the drainage tube (the technique of delayed port closure) (Figure 2). After the application of this technique, to our knowledge, no more trocar site hernias were observed following laparoscopic surgery in our institution. However, further studies are still needed to verify the safety and efficiency of this method.

Although it is a rare complication, TSH should be given attention due to the risk of life-threatening consequences. Based on lessons from the described case and review of the literature, we recommend the following: First, all layers of the abdomen should be carefully closed under direct vision at the trocar site more than 10 mm, especially where the drainage tube is placed, as well as at 5 mm port site if necessary. Second, TSH must be kept in mind during the differential diagnosis of post-laparoscopic obstruction, especially after the removal of drains. Patients should be carefully observed for at least 24 h after the removal of the intraabdominal drainage tube, avoiding a subsequent delay in diagnosis and treatment. Third, emergency image examination, especially abdominal CT scans, should be applied if TSH is suspected. Once TSH is identified, emergency exploratory laparotomy or laparoscopy should be undertaken for hernia reduction. Our simple and practical method of preventing TSH is a new strategy worthy of clinical promotion.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Mazeh H S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Swank HA, Mulder IM, la Chapelle CF, Reitsma JB, Lange JF, Bemelman WA. Systematic review of trocar-site hernia. Br J Surg. 2012;99:315-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Dulskas A, Lunevičius R, Stanaitis J. A case report of incisional hernia through a 5 mm lateral port site following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Minim Access Surg. 2011;7:187-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Schmocker RK, Greenberg JA. An Unusual Trocar Site Hernia after Prostatectomy. Case Rep Surg. 2016;2016:3257824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zemet R, Mazeh H, Grinbaum R, Abu-Wasel B, Beglaibter N. Incarcerated hernia in 11-mm nonbladed trocar site following laparoscopic appendectomy. JSLS. 2012;16:178-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ramalingam M, Senthil K, Murugesan A, Pai M. Early-onset port site (drain site) hernia in pediatric laparoscopy: a case series. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2012;22:416-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Moreaux G, Estrade-Huchon S, Bader G, Guyot B, Heitz D, Fauconnier A, Huchon C. Five-millimeter trocar site small bowel eviscerations after gynecologic laparoscopic surgery. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009;16:643-645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Manigrasso M, Anoldo P, Milone F, De Palma GD, Milone M. Case report of an uncommon case of drain-site hernia after colorectal surgery. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;53:500-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Fear RE. Laparoscopy: a valuable aid in gynecologic diagnosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1968;31:297-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tonouchi H, Ohmori Y, Kobayashi M, Kusunoki M. Trocar site hernia. Arch Surg. 2004;139:1248-1256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Velasco JM, Vallina VL, Bonomo SR, Hieken TJ. Postlaparoscopic small bowel obstruction. Rethinking its management. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:1043-1045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Shaher Z. Port closure techniques. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1264-1274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Duron JJ, Hay JM, Msika S, Gaschard D, Domergue J, Gainant A, Fingerhut A. Prevalence and mechanisms of small intestinal obstruction following laparoscopic abdominal surgery: a retrospective multicenter study. French Association for Surgical Research. Arch Surg. 2000;135:208-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Komuta K, Haraguchi M, Inoue K, Furui J, Kanematsu T. Herniation of the small bowel through the port site following removal of drains during laparoscopic surgery. Dig Surg. 2000;17:544-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |