Published online Dec 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i24.6337

Peer-review started: August 18, 2020

First decision: September 13, 2020

Revised: October 2, 2020

Accepted: October 26, 2020

Article in press: October 26, 2020

Published online: December 26, 2020

Processing time: 123 Days and 7.9 Hours

Chronic neutrophilic leukemia (CNL) is a rare bone marrow proliferative tumor and a heterogeneous disorder. In 2016, the World Health Organization included activating mutations in the CSF3R gene as one of the diagnostic criteria, with CSF3R T618I being the most common mutation. The disease is often accompanied by splenomegaly, but no developmental abnormalities and significant reticular fibrosis, and no Ph chromosome and BCR-ABL fusion gene. So, it is difficult to diagnose at the first presentation in the absence of classical symptoms. Herein we describe a rare CNL patient without splenomegaly whose initial diagnostic clue was neutrophilic hyperactivity.

The patient is an 80-year-old Han Chinese man who presented with one month of fatigue and fatigue aggravation in the last half of the month. He had no splenomegaly, but had persistent hypofibrinogenemia, obvious skin bleeding, and hemoptysis, and required repeated infusion of fibrinogen therapy. After many relevant laboratory examinations, histopathological examination, and sequencing analysis, the patient was finally diagnosed with CNL [CSF3R T618I positive: c.1853C>T (p.T618I) and c.2514T>A (p.C838)].

The physical examination and blood test for tumor-related genes are insufficient to establish a diagnosis of CNL. Splenomegaly is not that important, but hyperplasia of interstitial neutrophil system and activating mutations in CSF3R are important clues to CNL diagnosis.

Core Tip: An 80-year-old man had a long history of interstitial pneumonia. His leukocyte levels were extremely high, while the fibrinogen and prothrombin activities were low. His urea, uric acid, and creatinine values were high, and there were reticulated fibers around the blood vessels, and bone marrow fibrosis was obvious. His granulocyte system was extremely hyperplastic. Importantly, our gene mutation test found that the CSF3R gene was mutated. Therefore, we eventually diagnosed his symptoms as chronic neutrophilic leukemia (CNL). The particularity of the case lies in that CNL is often accompanied by splenomegaly, but the patient had no splenomegaly.

- Citation: Li YP, Chen N, Ye XM, Xia YS. Eighty-year-old man with rare chronic neutrophilic leukemia caused by CSF3R T618I mutation: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(24): 6337-6345

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i24/6337.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i24.6337

Chronic neutrophilic leukemia (CNL) is an extremely rare myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN)[1]. It is a heterogeneous disease, clinically characterized by the continuous increase of mature neutrophils, which could be attributed to CSF3R mutations, with peripheral blood accompanied by little or no naive granulocytes, monocytes, and basophils[2]. There is usually splenomegaly and hyperplasia of bone marrow granulocytes, the disease is not accompanied by dysplasia and significant reticular fibrosis, and there is no Ph chromosome or BCR/ABL fusion gene[3]. The incidence of the disease is low, and it is easy to be misdiagnosed and missed.

One month of fatigue and fatigue aggravation in the last half of the month.

The patient is an 80-year-old Han Chinese man who presented with fatigue and fatigue aggravation for half of the month (August 2019-October 2019).

The patient had a history of interstitial pneumonia for 5 years. He denied a history of chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, or heart disease. He denied any history of infection such as tuberculosis and hepatitis. He denied any drug allergies. He had no smoking or drinking history.

There was no family history of systemic autoimmune disease, cardiovascular disease, coagulation dysfunction, or malignancy, and any other family history.

The patient’s vital signs were stable and normal (temperature: 36.5 °C; pulse rate: 76/min; respiration rate: 19 breaths/min; blood pressure: 130/80 mmHg). Lung auscultation demonstrated heavy breath sounds and a small amount of wet and dry rales can be heard. Liver, spleen, and kidney examinations showed no obvious abnormalities. The patient was characterized by mild anemia with large ecchymosis on the outside of the left thigh, and the sternal tenderness was positive.

The laboratory findings were as follows: Platelet count was 102 × 109/L, leucocyte count was 324.06 × 109/L, neutrophil count was 285.38 × 109/L, and hemoglobin concentration was 100 g/L. Regarding coagulation function, the patient’s fibrinogen was 0.6 g/L (normal value: 2-4 g/L), and prothrombin activity was 46.1% (normal value: 80-120 g/L). His procalcitonin was 0.701 ng/mL. The five tests of respiratory tract infection pathogen antibody were all negative. The renal function indexes were as follows: UREA was 9.7 mmol/L; creatinine was 169.3 μmol/L; and uric acid was 844 μmol/L. with regard to routine urine examination, his occult blood was 1 + Ca25Ery/μL, urine protein was 1 + 0.3 g/L, and ferroprotein was greater than 1650 ng/mL. The autoantibodies and anti-neutrophil PMN antibodies were negative. Constant element, G/GM test, and fecal examination were all normal.

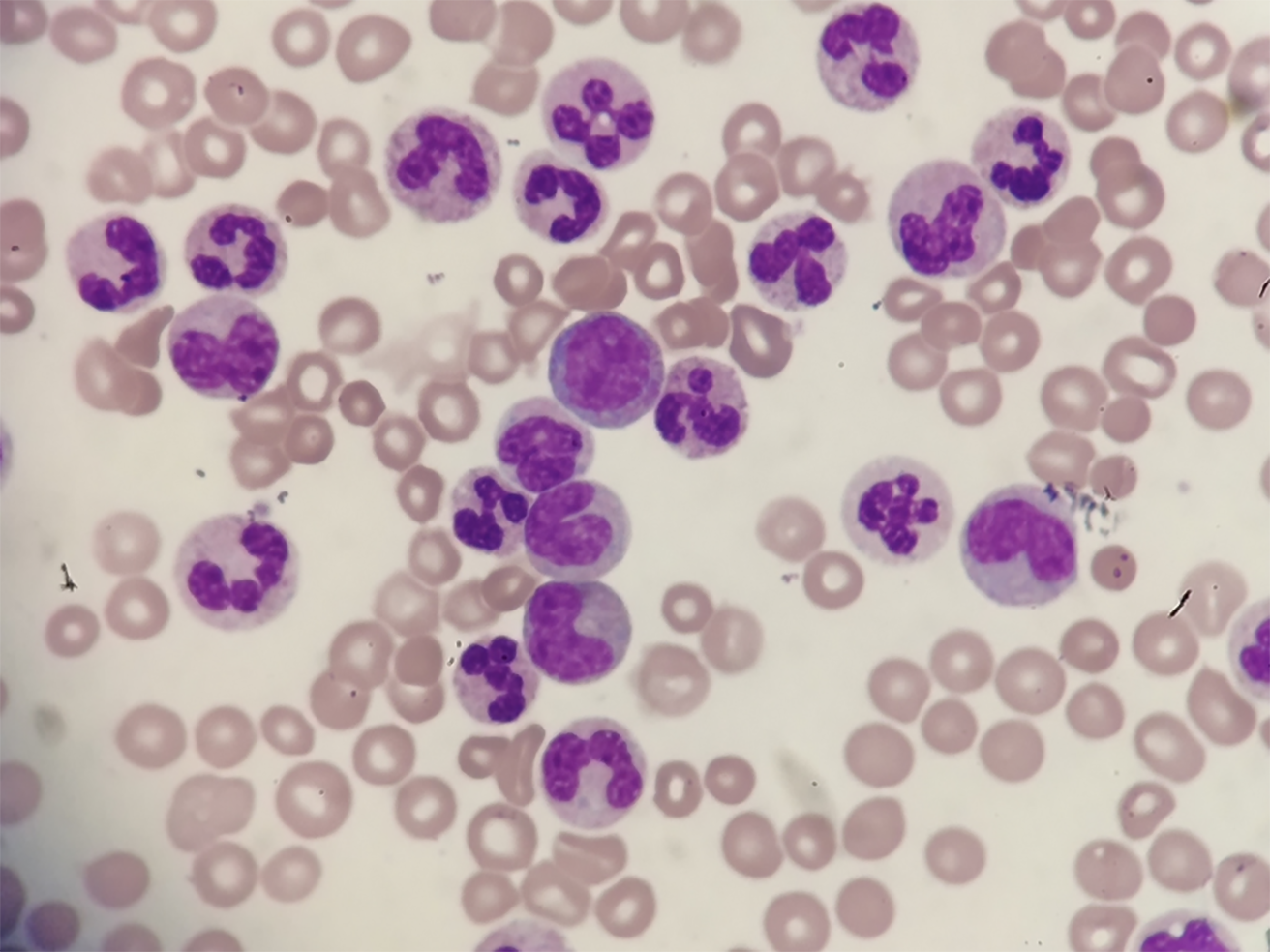

The result of blood film test was that more than 80% were neutral rod-shaped nuclei and neutral lobulated nuclear granulocytes (Figure 1). Naive cells (promyelocytes, myelocytes, and metamyelocytes) were less than 10%. No primitive granulocytes were seen, and no granulocytes were abnormally developed.

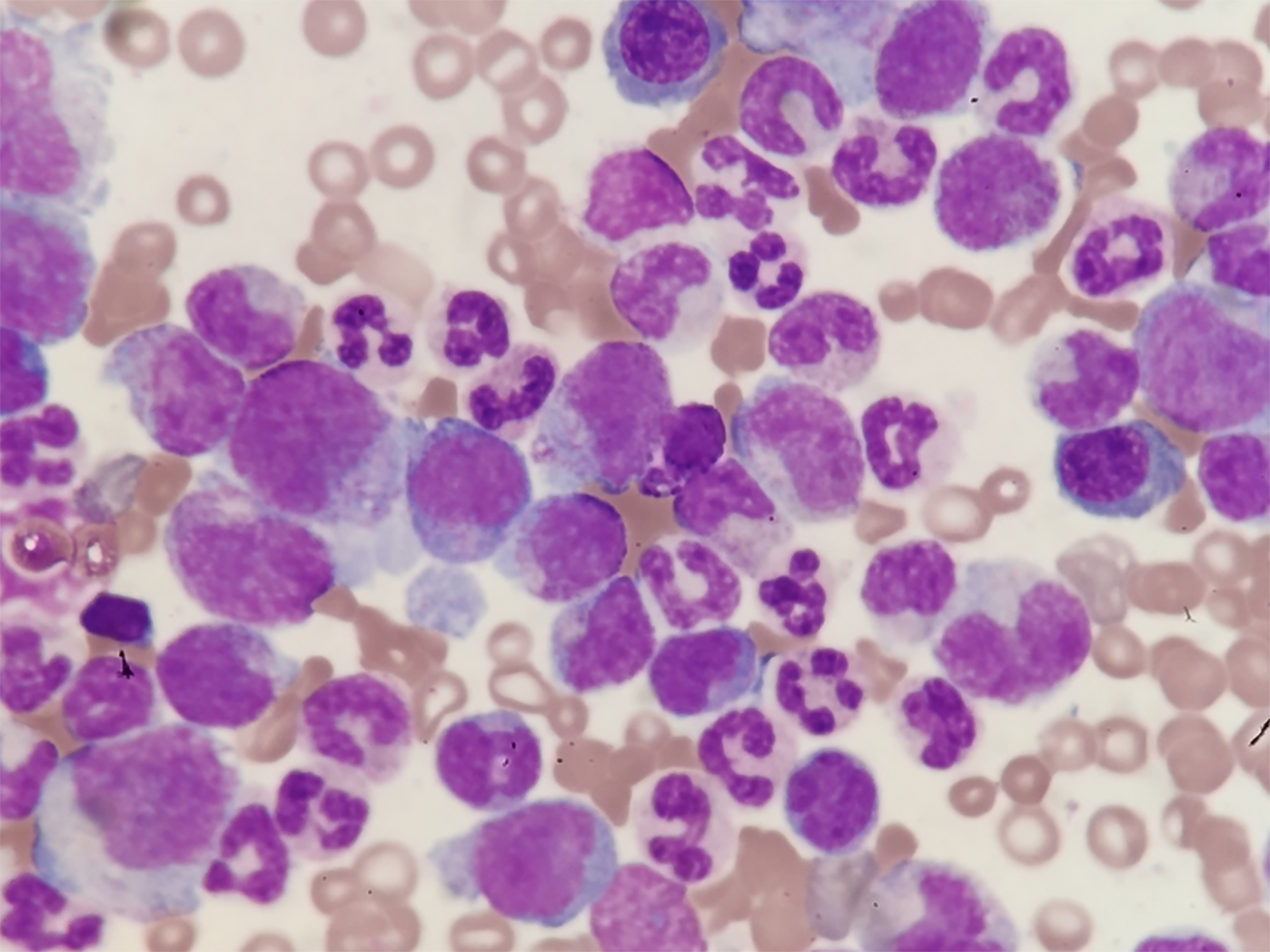

The bone marrow report was as follows: Myeloproliferation was extremely active (Figure 2). The interstitial neutrophil system was extremely proliferative, mainly mesenchymal and below-stage cells, and there was no increase in eosinophils. Bone marrow erythroids were rare, and megakaryocytes had not increased.

Comori staining showed that the reticular fibers were positive; bone marrow fibrosis was classified as MF-1.

No abnormal karyotype.

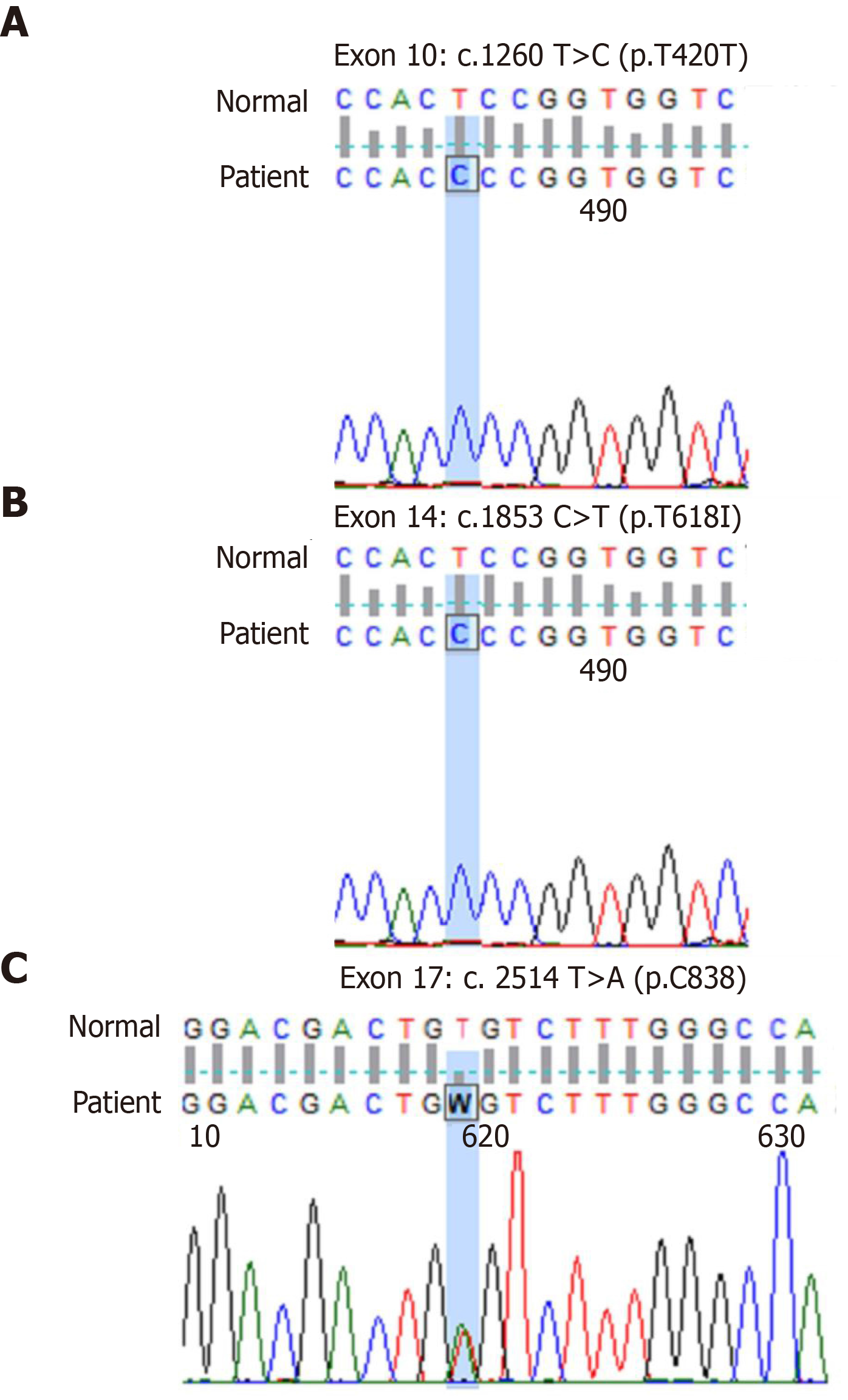

The CSF3R mutations in patients were determined by Beijing Hester Medical Laboratory Co. LTD (Beijing, China). BCR/ABL-190, -210, and -230 fusion genes were all negative. PML/RARa and S/V fusion genes were all negative. No MPN-related gene mutations were detected: W515L mutant, W515K mutant, JAK2/V617F mutant, CALR gene exon 9, PDGFRB, PDGFRA, FIPIL1/PDGFRα, and JAK2 gene exon 12 were all negative. More importantly, the key to this diagnosis was that we found a CSF3R T618I mutation. The details of the three CSF3R mutations are shown in Figure 3A-3C and Table 1.

| Testing content | Exons 1-17 of CSF3R | ||||

| Method | PCR & gene sequencing | ||||

| Gene | Exon | Variation type | Variation point | Remarks | |

| Results | CSF3R (NM_156039) | 1 | None | None | None |

| 2 | None | None | None | ||

| 3 | None | None | None | ||

| 4 | None | None | None | ||

| 5 | None | None | None | ||

| 6 | None | None | None | ||

| 7 | None | None | None | ||

| 8 | None | None | None | ||

| 9 | None | None | None | ||

| 10 | Synonymous mutation | c.1260T>C (p.T420T) | This mutation leads to premature termination of peptide synthesis | ||

| 11 | None | None | None | ||

| 12 | None | None | None | ||

| 13 | None | None | None | ||

| 14 | Missense mutation | c.1853C>T (p.T618I) | This is a specific mutation of CNL and aCML, and it is a pathological mutation | ||

| 15 | None | None | None | ||

| 16 | None | None | None | ||

| 17 | Nonsense mutation | c.2514T>A (p.C838) | This mutation leads to protein premature termination |

CNL is a rare BCR/ABL-negative myeloproliferative tumor. In 2013, it was discovered that the CSF3R T618I mutation is a highly specific and sensitive molecular diagnostic marker of CNL. In 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) identified CSF3R mutation as a CNL diagnostic marker. In the present case, we detected a c.1853C>T (p.T618I) mutation (heterozygous). According to the current literature, this is a specific mutation of CNL and atypical chronic myelocytic leukemia (aCML), and it is a pathological mutation[4]. Furthermore, the patient’s peripheral blood leukocyte count was 324.06 × 109/L (> 25 × 109/L), the neutral lobulated nuclei and rods were more than 80%, immature cells (promyeloid, medium, and late granulocytes) were less than 10%, and there were no primordial granulocytes and no granulocytes dysplasia. The myeloid hyperplasia was hyperactive, the granulocyte system in the stroma was hyperproliferating, mainly the cells in the middle and young granulocytes and the following stages, and megakaryocytes were not increased. All the fusion genes of BCR/ABL-190, -210, and -230 were negative. No MPN-related mutations were detected. Pointing away from CNL is absence of hepatosplenomegaly and this patient also had a c.1260T>C (p.T420T) mutation (no pathogenicity) and a c.2514 T>A (p.C838) mutation (the mutation results in a frame shift and premature termination of the amino acid coding). In addition, the patient had persistent low fibrinogenemia, obvious skin bleeding, and hemoptysis.

The patient was diagnosed with chronic neutrophil leukemia, hypofibrinogenemia, uric acid nephropathy, and interstitial pneumonia.

The patient received hydroxymethylnicotinamide tablets, sodium bicarbonate tablets, and allopurinol tablets. Oral administration of hydroxymethylnicotinamide tablets was given to lower cells with fluid replacement, and sodium bicarbonate tablets combined with allopurinol tablets were prescribed to alkalinize urine.

The patient had obvious bleeding symptoms such as skin bleeding and hemoptysis, and these symptoms were relieved after fibrinogen supplementation and cryoprecipitation treatment. This patient had severe pulmonary infection with type Ι respiratory failure during treatment, and the symptoms improved after anti-infection and hormone therapy.

When the patient was discharged, the blood leukocytes dropped to normal levels, the kidney function was normal, and fibrinogen was normal. The bleeding symptoms and the lung infection were controlled.

The patient was intermittently treated with hydroxyurea (0.5 g, oral, 1-2 times/d) for maintenance treatment after discharge from hospital. The blood routine was reviewed weekly, and the dosage of the drug was adjusted according to the routine blood results.

We followed the patient for 3 mo, and 3 mo after discharge, the patient died because of a lung infection.

CNL is a clinically rare hematological tumor. It was first reported by Tuohy[5] in 1920. In 2001, WHO confirmed its diagnostic classification and classified it as a myeloproliferative tumor[6]. In 2008, the WHO revised the disease diagnostic criteria (as mentioned above)[7]. Large-scale epidemiological studies on the disease are lacking. According to comprehensive literature case reports, the incidence rate among the elderly is high, which is consistent with the present report (the patient was 80 years old)[8]. More men than women have a poor prognosis, with a median survival time of 23.5 mo[9].

Fatigue is the most common symptom at the initial diagnosis of this disease[10]. In this report, the patient had obvious fatigue and had extreme fatigue for half a month. Other symptoms include weight loss, skin ecchymosis, abdominal distension, anorexia, and night sweats[11]. Similarly, a large ecchymosis can be seen on the lateral side of his left thigh. Lymphadenopathy and hepatomegaly are not common[12]. Hepatosplenomegaly, one of the main features of CNL, is a key indicator to distinguish leukemoid reaction from CNL[13,14]. Most patients with CNL have hepatosplenomegaly at the time of diagnosis, but hepatosplenomegaly is not common in the pathological manifestations of leukemoid reaction. Furthermore, leukemoid reaction is a leukemia-like blood reaction that the body is stimulated by certain diseases or external factors, among which neutrophil type is the most common. Patients with leukemoid reaction have no hepatomegaly or splenomegaly, the total number of white blood cells in the patients can reach 50 × 109/L, and the total number of myeloblasts, primitive cells, and young granulocytes increases[15]. In the present report, the number of white blood cells of the patient was increased to 324.06 × 109/L, and the young granulocytes also increased. Most unusually, no splenomegaly can be seen, which greatly increased the probability of misdiagnosis of CNL. It suggests that the characteristics of splenomegaly might need careful consideration to avoid misdiagnosis.

The unexplained rise of leukocytes and mature neutrophils is a key characteristic of this disease[16]. It should be noted that the increase of CNL leukocytes is not accompanied by the increase of monocytes, eosinophils, and basophils, abnormal development of granulocytes, or a significant increase in naive granulocytes[17]. The patient in this report had fatigue at the first diagnosis, the leukocytes were significantly increased, and infections and tumors were excluded. More than 80% of mature granulocytes were immature granulocytes and monocytes. Judging from the 2008 WHO diagnostic criteria, five of the eight diagnostic criteria belong to the excluded diagnosis. We performed a CML fusion gene or chromosome examination at the time of diagnosis, excluding CML diagnosis[18]. The patient had no elevated eosinophils. We also tested for W515L, W515K, JAK2/V617F, exon 9 of CALR, PDGFRB, PDGFRA, FIPIL1/PDGFRα, and JAK2 genes related to MPN tumors, which ruled out this type of disease[19-21]. The patient had mildly reduced hemoglobin and normal range platelet count (102 × 109/L), but on the low side. Combined with bone marrow examination, MPN can be excluded. CNL is similar to aCML and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) in clinical manifestations, cytogenetics, and molecular biology[18]. Special attention should be paid to the diagnosis of CNL. Peripheral blood naive granulocyte ratio in aCML patients is greater than 10%, while peripheral blood mononuclear cells in CMML patients continue to be greater than 1 × 109/L. Moreover, the changes in the number of mononuclear cells in the bone marrow can be used to identify aCML and CMML[18,22]. In the present report, the case had a less than 10% blood naive granulocytes ratio (including early, medium, and late cells) and had a normal ratio of peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

In early 2013, Maxson et al[23] and Pardanani et al[24] discovered a CSF3R mutation, which has milestone significance for the diagnosis of CNL. CSF3R mutation confirmed the presence of myeloid clones and ruled out other blood tumors. The CSF3R mutation occurred in more than 90% of patients who met the 2008 WHO diagnostic criteria for CNL. The CSF3R mutation determined the WHO diagnostic criteria for CNL at the molecular level. Two types of mutations were found in CSF3R: CSF3R T618I and CSF3R T615A[23,25], which result in differential sensitivity to inhibition of tyrosine kinases downstream of CSF3R. CSF3R is a member of the hematopoietic cell receptor superfamily. It is located on chromosome 1p34.3 and has the functions of promoting the proliferation, survival, and differentiation of neutrophils. Although CSF3R itself has no endogenous tyrosine kinase activity, it can change its conformation through ligand binding to stimulate a variety of tyrosine kinases related to its cell activity range, including JAKs, SRC kinase family, and tyrosine kinase. And important signaling pathways involved include STAT, PI3K-AKT, and RAS-MAPK[11,24,26], showing that its mechanism of action is very complicated. As the latest research results, mutations of CSF3R are related to many diseases, most of which are related to myeloid system diseases, such as hereditary neutropenia (severe congenital neutropenia), myelodysplastic syndrome, AML, and CNL[26]. T618I is the most frequent mutation[24], and CSF3R mutations were also detected in our patient, including CSF3R T618I mutation, T420T synonymous mutation, and C838 mutation. It has been reported that JAK2/V617F mutation has been detected in a small number of diagnosed CNL patients, but the incidence is low and the specificity is poor[27]. The mutations in the JAK2/V617F gene and exon 12 of JAK2 gene were undetectable in our patient.

Plasma fibrinogen is mainly used as a diagnostic indicator for coagulation diseases. Recent studies have found that plasma fibrinogen levels in patients with various malignant tumors are significantly elevated, and are closely related to the occurrence and development, recurrence, and metastasis of malignant tumors[28]. However, the characteristics of hypofibrinogenemia appeared in the present case, which is difficult to explain. Although reports on the characteristics of hypofibrinogenemia in CNL patients are extremely rare, this deserves the attention of clinicians.

The current commonly used treatment methods for CNL include hydroxycarbamide, interferon-alpha, and induction chemotherapy, which can alleviate the symptoms of CNL, but there is no significant improvement to the survival of CNL patients[20,29,30]. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is considered an effective method for curing the disease, but the incidence of transplant-related death and transplant-related complications is high[31]. In the present case, after oral administration with the nucleotide reductase inhibitor hydroxycarbamide, the number of leukocytes dropped to normal levels. After discharge, hydroxycarbamide was used intermittently for maintenance therapy. Routine blood test was reviewed weekly, and drug dosage was adjusted according to routine blood test results.

With the disclosure of CSF3R gene mutation, CNL targeted therapy was born. The JAK1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib was used to treat a CNL patient with CSF3R T618I mutation[32,33], and achieved a dose-dependent clinical effect. At present, the diagnosis and treatment of CNL in China are still a problem. With the popularization of CSF3R mutation gene detection and the application of targeted drugs, the diagnosis of CNL will be clearer and the prognosis will be improved.

CNL treatment is still a great challenge for clinicians. The regular features are insufficient for the diagnosis of CNL. In this case, the patient had combined multiple diseases. Therefore, early genetic screening, multidirectional drug treatment, and comprehensive consideration of the treatment effect are necessary means of prevention and diagnosis. Targeted therapy for CSF3R will be more beneficial to the clinical individualized treatment and accurate prognosis assessment.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Langabeer SE S-Editor: Huang P L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Bain BJ, Ahmad S. Chronic neutrophilic leukaemia and plasma cell-related neutrophilic leukaemoid reactions. Br J Haematol. 2015;171:400-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Elliott MA, Tefferi A. Chronic neutrophilic leukemia: 2018 update on diagnosis, molecular genetics and management. Am J Hematol. 2018;93:578-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Vardiman J, Hyjek E. World health organization classification, evaluation, and genetics of the myeloproliferative neoplasm variants. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2011;2011:250-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Druhan LJ, McMahon DP, Steuerwald N, Price AE, Lance A, Gerber JM, Avalos BR. Chronic neutrophilic leukemia in a child with a CSF3R T618I germ line mutation. Blood. 2016;128:2097-2099. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tuohy E. A case of splenomegaly with polymorphonuclear neutrophil hyperleukocytosis. Am J Med Sci. 1920;160:18-24. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Vardiman JW, Harris NL, Brunning RD. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of the myeloid neoplasms. Blood. 2002;100:2292-2302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1492] [Cited by in RCA: 1460] [Article Influence: 63.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, Thiele J. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. 4th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2008; 2: Available from: http://origin.searo.who.int/publications/bookstore/documents/17024002/en/. |

| 8. | Yin B, Chen X, Gao F, Li J, Wang HW. Analysis of gene mutation characteristics in patients with chronic neutrophilic leukaemia. Hematology. 2019;24:538-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Elliott MA, Hanson CA, Dewald GW, Smoley SA, Lasho TL, Tefferi A. WHO-defined chronic neutrophilic leukemia: a long-term analysis of 12 cases and a critical review of the literature. Leukemia. 2005;19:313-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mitsumori T, Komatsu N, Kirito K. A CSF3R T618I Mutation in a Patient with Chronic Neutrophilic Leukemia and Severe Bleeding Complications. Intern Med. 2016;55:405-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Menezes J, Cigudosa JC. Chronic neutrophilic leukemia: a clinical perspective. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;8:2383-2390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Szuber N, Tefferi A. Chronic neutrophilic leukemia: new science and new diagnostic criteria. Blood Cancer J. 2018;8:19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hoofien A, Yarden-Bilavski H, Ashkenazi S, Chodick G, Livni G. Leukemoid reaction in the pediatric population: etiologies, outcome, and implications. Eur J Pediatr. 2018;177:1029-1036. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Silva PR, Ferreira C, Bizarro S, Cerveira N, Torres L, Moreira I, Mariz JM. Diagnosis, complications and management of chronic neutrophilic leukaemia: A case report. Oncol Lett. 2015;9:2657-2660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kumar A, Kumar P, Basu S. Enterococcus fecalis Sepsis and Leukemoid Reaction: An Unusual Association at Birth. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2015;37:e419-e420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Elliott MA, Dewald GW, Tefferi A, Hanson CA. Chronic neutrophilic leukemia (CNL): a clinical, pathologic and cytogenetic study. Leukemia. 2001;15:35-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Otgonbat A, Zhao M. Current strategies in the diagnosis and management of chronic neutrophilic leukemia. Chin Med J (Engl). 2014;127:4258-4262. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Zhang BS, Chen YP, Lv JL, Yang Y. Comparison of the Efficacy of Nilotinib and Imatinib in the Treatment of Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2019;29:631-634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Li B, Gale RP, Xiao Z. Molecular genetics of chronic neutrophilic leukemia, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia and atypical chronic myeloid leukemia. J Hematol Oncol. 2014;7:93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Stahl M, Xu ML, Steensma DP, Rampal R, Much M, Zeidan AM. Clinical response to ruxolitinib in CSF3R T618-mutated chronic neutrophilic leukemia. Ann Hematol. 2016;95:1197-1200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Cui Y, Li B, Gale RP, Jiang Q, Xu Z, Qin T, Zhang P, Zhang Y, Xiao Z. CSF3R, SETBP1 and CALR mutations in chronic neutrophilic leukemia. J Hematol Oncol. 2014;7:77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Elliott MA, Tefferi A. Chronic neutrophilic leukemia 2014: Update on diagnosis, molecular genetics, and management. Am J Hematol. 2014;89:651–658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Maxson JE, Gotlib J, Pollyea DA, Fleischman AG, Agarwal A, Eide CA, Bottomly D, Wilmot B, McWeeney SK, Tognon CE, Pond JB, Collins RH, Goueli B, Oh ST, Deininger MW, Chang BH, Loriaux MM, Druker BJ, Tyner JW. Oncogenic CSF3R mutations in chronic neutrophilic leukemia and atypical CML. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1781-1790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 414] [Cited by in RCA: 440] [Article Influence: 36.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Pardanani A, Lasho TL, Laborde RR, Elliott M, Hanson CA, Knudson RA, Ketterling RP, Maxson JE, Tyner JW, Tefferi A. CSF3R T618I is a highly prevalent and specific mutation in chronic neutrophilic leukemia. Leukemia. 2013;27:1870-1873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Fleischman AG, Maxson JE, Luty SB, Agarwal A, Royer LR, Abel ML, MacManiman JD, Loriaux MM, Druker BJ, Tyner JW. The CSF3R T618I mutation causes a lethal neutrophilic neoplasia in mice that is responsive to therapeutic JAK inhibition. Blood. 2013;122:3628-3631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Liongue C, Ward AC. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor mutations in myeloid malignancy. Front Oncol. 2014;4:93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Wu XB, Wu WW, Zhou Y, Wang X, Li J, Yu Y. Coexisting of bone marrow fibrosis, dysplasia and an X chromosomal abnormality in chronic neutrophilic leukemia with CSF3R mutation: a case report and literature review. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ma Y, Qian Y, Lv W. The correlation between plasma fibrinogen levels and the clinical features of patients with ovarian carcinoma. J Int Med Res. 2007;35:678-684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Yassin MA, Kohla S, Al-Sabbagh A, Soliman AT, Yousif A, Moustafa A, Battah AA, Nashwan A, Al-Dewik N. A case of chronic neutrophilic leukemia successfully treated with pegylated interferon alpha-2a. Clin Med Insights Case Rep. 2015;8:33-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Shi J, Ni Y, Li J, Qiu H, Miao K. Concurrent chronic neutrophilic leukemia blast crisis and multiple myeloma: A case report and literature review. Oncol Lett. 2015;9:2208-2210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Itonaga H, Ota S, Ikeda T, Taji H, Amano I, Hasegawa Y, Ichinohe T, Fukuda T, Atsuta Y, Tanizawa A, Kondo T, Miyazaki Y. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for the treatment of BCR-ABL1-negative atypical chronic myeloid leukemia and chronic neutrophil leukemia: A retrospective nationwide study in Japan. Leuk Res. 2018;75:50-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Lasho TL, Mims A, Elliott MA, Finke C, Pardanani A, Tefferi A. Chronic neutrophilic leukemia with concurrent CSF3R and SETBP1 mutations: single colony clonality studies, in vitro sensitivity to JAK inhibitors and lack of treatment response to ruxolitinib. Leukemia. 2014;28:1363-1365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Dao KH, Solti MB, Maxson JE, Winton EF, Press RD, Druker BJ, Tyner JW. Significant clinical response to JAK1/2 inhibition in a patient with CSF3R-T618I-positive atypical chronic myeloid leukemia. Leuk Res Rep. 2014;3:67-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |