Published online Dec 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i24.6274

Peer-review started: September 27, 2020

First decision: October 27, 2020

Revised: November 4, 2020

Accepted: November 14, 2020

Article in press: November 14, 2020

Published online: December 26, 2020

Processing time: 83 Days and 12.8 Hours

In children, it is common to see failure and recurrence in the correction of epiblepharon and to have reoperation due to obvious irritation symptoms and corneal injury.

To explore the causes of failure and recurrence after epiblepharon correction in children, to remove accurately redundant epiblepharon and orbicularis oculi muscle in patients via the cilia-everting suture technique combined with lid margin splitting in some patients due to inverted lashes in the medial part of the eyelid, and to observe the therapeutic effect.

From 2015 to 2019, in the Outpatient Department of Ophthalmology of Beijing Tongren Hospital, 22 children (40 eyes) with epiblepharon, aged 5-12 years, were treated due to correction failure and recurrence. Fourteen patients (28 eyes) underwent the full-thickness everting suture technique, and eight patients (16 eyes) underwent incisional surgery. They were treated by reviewing the previous surgical methods and observing epiblepharon, eyelash direction, and corneal injury. During reoperation, a subciliary incision was made 1 mm below the inferior lash line. Incisional surgery for the lower eyelid was used to remove accurately redundant epiblepharon and part of the pretarsal orbicularis muscle. Subcutaneous tissue and the orbicularis muscle of the upper skin-muscle flap were anchored to the anterior fascia of the tarsal plate by rotational sutures. Lid margin splitting was used only for patients who had seriously inverted lashes located in the medial part of the eyelid. All patients were followed for 6-12 mo after reoperation to observe the lower eyelid position, skin incision, eyelash direction, corneal damage, and recurrence.

After reoperation, all the patients were corrected. Photophobia, rubbing the eye, winking, and tearing disappeared. There was no lower eyelid entropion, ectropion, or retraction. There was no obvious sunken scar or lower eyelid crease. The eyelashes were far away from the cornea, and when the patients looked down, the eyelashes on the lower eyelid did not contact the cornea or conjunctiva. The corneal injuries were repaired. Follow-up observation for 6 mo showed no recurrence of epiblepharon.

The type of suture method, the failure to remove accurately redundant skin and orbicularis muscle, the lack of cilia rotational suture use, and excessive reverse growth of eyelashes are the main causes of failure and recurrence after epiblepharon correction in children.

Core Tip: It is common for children to have failure and recurrence in the correction of epiblepharon and to need reoperation due to obvious irritation symptoms and corneal injury.

- Citation: Wang Y, Zhang Y, Tian N. Cause analysis and reoperation effect of failure and recurrence after epiblepharon correction in children. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(24): 6274-6281

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i24/6274.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i24.6274

Epiblepharon is defined as an extra horizontal fold of skin that stretches across the margin of the eyelid and underling orbicularis muscle that causes inversion of the eyelashes against the cornea of children. It is manifested by the overriding of the anterior lamella over the posterior lamella, resulting in lashes brushing the ocular surface. At the same time, it can also cause ocular irritation and corneal injury, especially in the down-gaze[1-3]. Before 3-years-old, because eyelashes are very soft, corneal damage is rarely caused. Epiblepharon most commonly involves bilaterally the lower eyelid among East Asian children and usually affects the nasal half of the lower eyelid. It associated with inverted eyelashes touching the cornea, occurs in infants, and decreases spontaneously with age[4]. Surgical correction is widely carried out when corneal injury and irritation symptoms persist despite conservative medical treatment. It is common to see children who have failed and have recurrence in the correction of epiblepharon and need reoperation due to obvious irritation symptoms and corneal injury.

Previous literature rarely reported the reasons for the failure and recurrence of the correction surgery of epiblepharon and the operation skills that should be in place in reoperation correction. Improving the success rate of surgery for children with epiblepharon can help to reduce the number of exposures to general anesthesia and the risk of anesthesia, reduce the disease and pain caused by surgery, and reduce the economic burden of children's families caused by multiple operations. As far as we know, this study is the first to analyze the causes of failure and recurrence of epiblepharon in children, and to summarize the operation skills for reoperation.

From 2014 to 2019, 22 patients (40 eyes) with correction of epiblepharon failure and recurrence, including 10 males and 12 females, aged 5-12 years (average age 8.5 years), were collected. Eighteen cases recurred in both eyes, and four cases recurred in one eye, all of which were accompanied by photophobia, tearing, and obvious corneal injury.

There were 14 patients who had only had suture correction. Ten of them had done suture correction once, three cases with suture correction twice, and one case with suture correction three times. Two cases underwent suturing correction and incisional surgery, once each, respectively. Six patients had done incisional surgery: four cases were corrected once, and two cases were corrected by incisional surgery twice. Twenty patients (40 eyes), including 36 eyes with obvious epiblepharon and four eyes without obvious epiblepharon, had abnormal direction of eyelashes and the lower eyelid eyelashes were still attached to the eyeball and cornea. Fourteen patients (28 eyes) underwent suture method, and 28 lower eyelids were accompanied by different degrees of epiblepharon, 28 eyes with lower eyelid trichiasis; eight cases (16 eyes) were treated by incisional surgery, 10 eyes were still accompanied with residual epiblepharon, and 12 eyes were accompanied with obvious trichiasis.

This study was a retrospective study conducted in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Ethics Committee of Beijing Tongren Hospital, Capital Medical University (TRECKY2020-063). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before surgical treatment.

Failure of corrective surgery was defined as patients who still had trichiasis at the time of suture removal 7 d after operation. If the trichiasis was corrected when the sutures were removed after surgery, but the trichiasis reappeared in the 3-6 mo after the follow-up, this was defined as recurrence after the correction operation. Among 14 cases (28 eyes) with suture method to correct epiblepharon, four eyes failed in the operation, and 24 eyes recurred after correction. Among eight cases (16 eyes) with epiblepharon corrected by incisional surgery, one eye failed and 11 eyes recurred. There were four eyes without recurrence in all patients. Because the lower eyelid eyelash extroversion was not ideal, and for the sake of symmetry and beauty of both eyes, reoperation was done together. The lower eyelids of both eyes of all relapsed patients were operated on at the same time, and all patients were operated under general anesthesia.

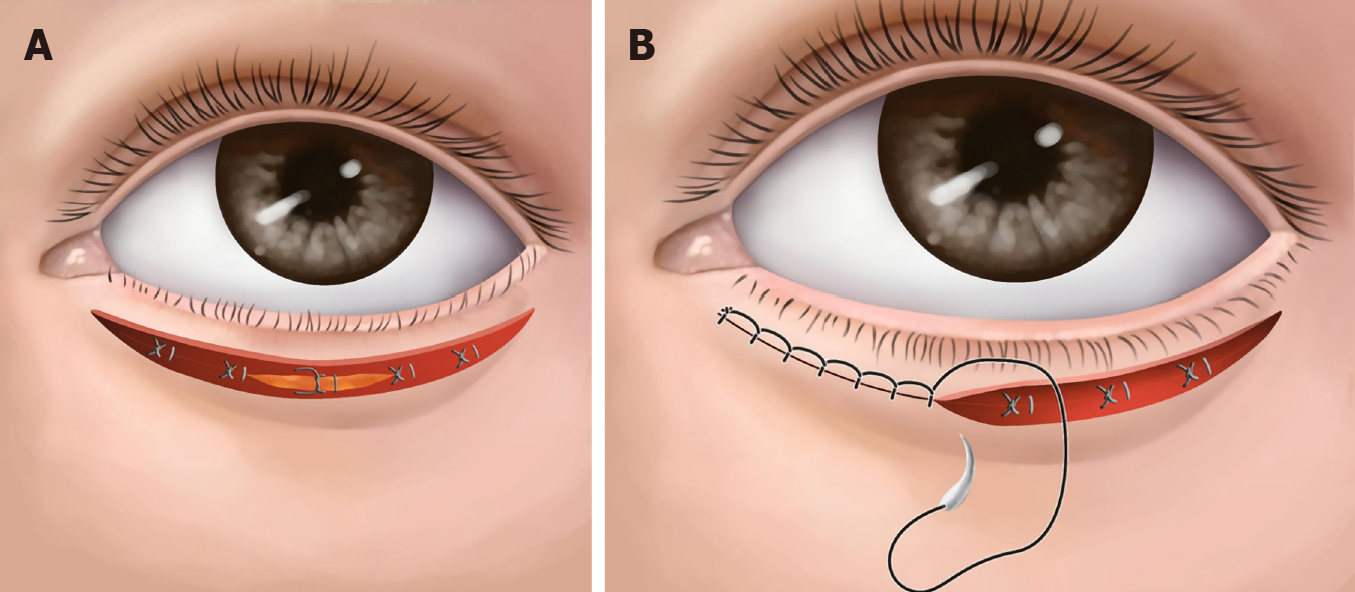

Patients took a supine position: (1) A line was precisely designed to remove excess skin and orbicularis oculi muscle. The upper subciliary incision was made 1 mm below the cilia line. This line was marked horizontally from the temporal point of the inferior punctum along the whole lid length. The lower skin incision line was the projection of the hidden lower eyelid eyelash root or the upper incision line on the lower eyelid skin; (2) Local infiltration of 2% lidocaine mixed with epinephrine at a ratio of 1:100000 was given subcutaneously along the marked line. Incisional surgery for the lower eyelid was used to remove redundant epiblepharon and part of pretarsal orbicularis muscle accurately; (3) At the same time, electrocoagulation was performed to stop bleeding, 6-8 points of electrocoagulation were performed on the subcutaneous tissue on the upper edge of the incision and the muscle tissue in front of the tarsus; (4) Subcutaneous tissue and the orbicularis of the upper skin-muscle flap were anchored to the anterior fascia in front of the tarsal plate by five to six stitches of cilia rotational suture with 7-0 absorbable suture (Figure 1A); (5) 8-0 Absorbable suture was used for continuous edge-locking suture to close the skin incision (Figure 1B); and (6) Lid margin splitting was used only for the 12 patients that had seriously inverted lashes located in the medial part of the eyelid. All trichiasis was corrected after operation. The suture was removed 7 d after the operation, and anti-inflammatory eye drops were given for 3 wk after operation.

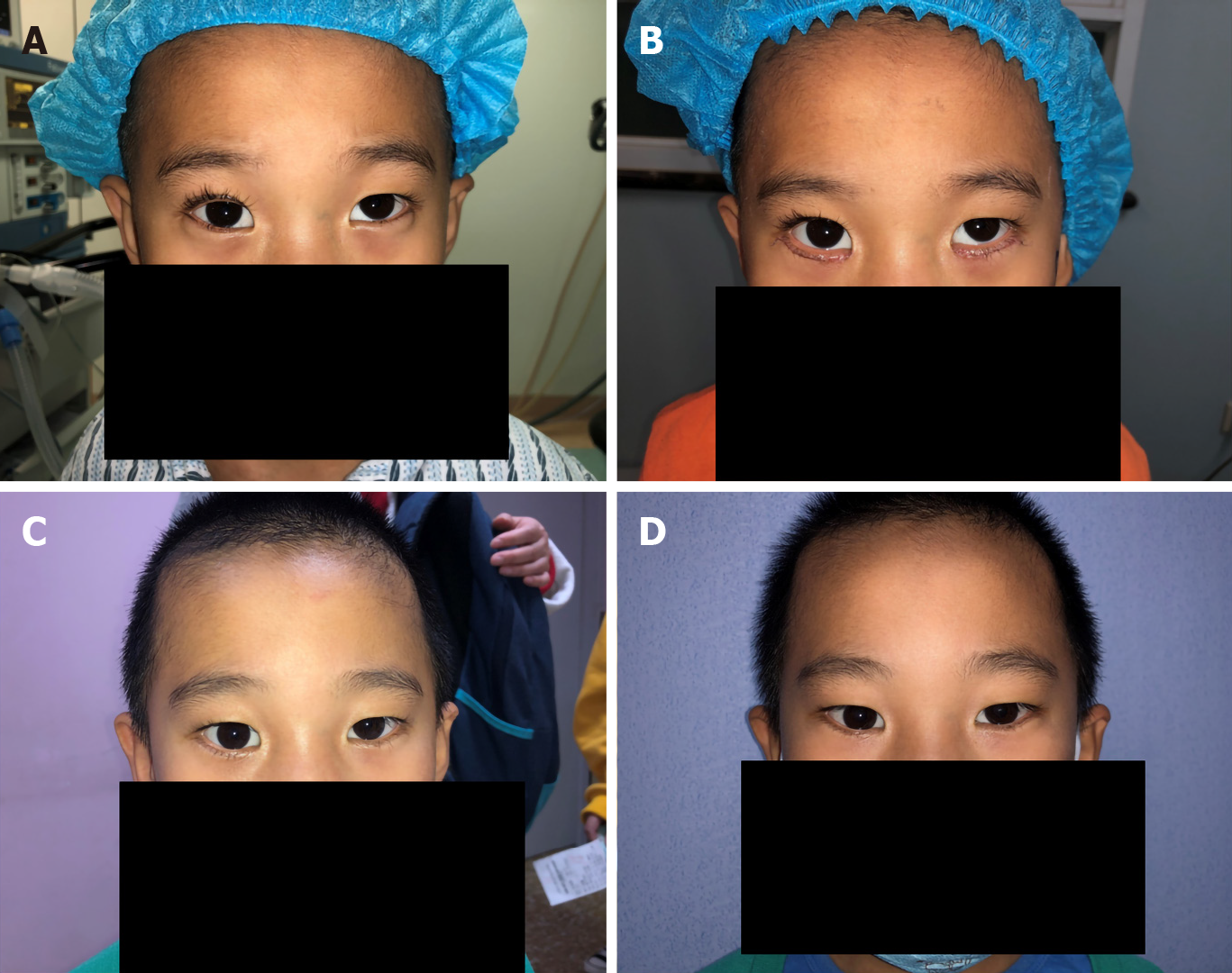

Seven days after the operation, the stitches were removed. When the stitches were removed, all corneal epithelial injuries were repaired, epiblepharon was corrected, and all the palpebral margin structures of the lower eyelid were exposed. Follow-up observation for 6-12 mo after operation showed that the symptoms of photophobia, tears, rubbing eyes, and winking disappeared. No recurrence was found after epiblepharon correction, no obvious lower eyelid crease, no obvious scar on the skin, no lower eyelid ectropion, no retraction, and no tear spot injury on the lower eyelid. The patients and their families were satisfied with the appearance and operation effect (Figure 2A and B and Figure 3A-D).

Eyelashes have dust-shielding, light, and esthetic functions. When eyelashes curl inward, they rub against the eyeballs, causing discomfort. Under a slit lamp, corneal epithelial punctate shedding and corneal opacity can be seen. In severe cases, local scars are formed, which affects vision. Some patients will develop obvious astigmatism and amblyopia[5,6].

It is generally believed that there are several etiologic factors leading to epiblepharon. The skin fold near the lower lid margin is a result of the pretarsal orbicularis muscle and skin is weakly attached to the tarsus below. Epiblepharon may also be caused by the failure of the lower eyelid retractor to gain access to the skin, the failure of interdigitation of septae in the subcutaneous plane, and hypertrophy of the orbicularis oculi muscle acting a sphincter muscle, thus facilitating the anterior-posterior overriding of lamellae. The varied degrees of epicanthal folds seen in patients may also contribute to epiblepharon. In addition, vertical or reverse growth of the lower eyelid eyelashes is also an important cause of epiblepharon[3,7,8].

The prevalence of epiblepharon in the Japanese population was reported to be 9.9% in an age group of 3 mo to 18 years[4]. Epiblepharon comprised 9.5% of the clinical cases of 623 patients who visited an oculoplastic surgery clinic in Singapore[9]. Infants and young children have soft eyelashes, and these generally do not damage the cornea. With the growth and development of children's faces and eyes, most children experience improved trichiasis with age. After the age of 3, because the eyelashes become longer, thicker, and harder, they stimulate the cornea and cause corneal injury, resulting in photophobia and tears. To avoid corneal injury, astigmatism, amblyopia, and influences on the development of visual power caused by trichiasis, surgical treatment can be considered. The most common indications for surgery are persistent symptoms and keratopathy[3]. In general, both eyelids should be treated, even in unilateral cases for bilateral symmetry[10].

First, the improper selection of surgical method is the main cause of surgical failure and recurrence. Suture correction and incisional surgery are two commonly used surgical methods to correct epiblepharon in children[11-13]. Suture correction is widely used in ophthalmology and plastic surgery because of its simplicity, and incisional surgery is widely used by professional eye plastic surgeons. In this study, 14 of the 22 patients who relapsed initially received the suture method for epiblepharon correction. These 14 patients had obvious epiblepharon, belonging to moderate and severe epiblepharon. Because the suture method is only suitable for correcting mild epiblepharon, it was not an ideal choice to use this surgical method in these patients. The suture method should be used only for mild epiblepharon; for moderate and severe cases of epiblepharon, there will be a higher recurrence rate because this method does not solve the issue of redundant skin and orbicularis oculi muscle[10,14]. Only three to four groups of sutures are used to form a lower eyelid crease, which may only be temporary, thus not lasting and affecting esthetic appearance; therefore, the families of children are not usually willing to accept this method. Many Asians do not have a lower eyelid crease and consider it undesirable; therefore, a prominent lower eyelid crease after epiblepharon surgery should be avoided in Asians[2,15]. Once the scar adhesions of the lower eyelid are released, epiblepharon and trichiasis will recur, so professional eye plastic surgeons rarely use this method. Sundar et al[3] reported that 44.4% of patients who underwent lid-everting sutures had undercorrection, and only 9.1% who underwent the Hotz procedure had undercorrection. The recurrence rate varied from 6.8% for patients who underwent the Hotz procedure to 66.7% for those who underwent lid-everting sutures.

Second, accurately planning the amount of skin removal of the lower eyelid is a factor for preventing failure and recurrence. It is key to design accurately the amount of lower eyelid skin and orbicularis oculi muscle to be removed during the operation, especially for children undergoing general anesthesia. The design depends on the rich experience and accurate judgment of the surgeon. Young doctors often worry about overcorrection and undercorrection due to lack of experience. It is particularly important to note that if the eye of the child is not in the primary position during general anesthesia surgery, whether the eyeball turns up or down, the depth of general anesthesia and the use of muscle relaxation drugs will affect the operator's judgment on the amount of removed skin. Among eight patients (14 eyes) who experienced failure and recurrence after incision correction, there was obvious residual epiblepharon in 10 lower eyelids.

In addition, the eyelash rotation fixation suture technique plays an important role in preventing postoperative recurrence[16,17]. The goal of this technique is to create adhesion between the anterior lamella of the lower eyelid and the lower eyelid retractors, thereby exerting an everting force on the eyelashes of the lower eyelid[18]. After epiblepharon correction and removing the orbicularis oculi muscle, the skin, muscle, tarsus, muscle, and skin, in order, were sutured intermittently instead of using eyelash rotation sutures, which provides fixation of the subcutaneous orbicularis oculi muscle tissue of the upper eyelid to the anterior fascia of the tarsus. Seven days after suture removal, the formation of scar adhesions was short and unreliable. After a long time, the scar adhesions were released, resulting in the recurrence of epiblepharon. A 7-0 absorbable suture is generally used for internal fixation of eyelash rotation sutures, which usually requires 5-6 stitches. The sutures will be absorbed after 2-3 mo. In the long absorption process of absorbable sutures, it can help to form firm and long-term scar adhesions and avoid the recurrence of epiblepharon[19-21]. After taking a detailed medical history and consulting the surgical records, four out of eight patients who underwent the incision method did not receive the eyelash rotation fixation suture technique.

For patients with stubborn trichiasis on the inside of the lower eyelid, vertical growth of eyelashes or reverse growth of eyelashes, and even "barb-like" eyelashes, if the direction of the eyelash is not ideal after eyelash rotation sutures, we can use the method of lid margin splitting along the gray line. This method increases the width of the eyelid margin, further increases the outward inclination of eyelashes, and increases the distance between eyelashes and the eyeball and cornea[22].

Finally, the surgical site was carefully inspected for hemostasis, and cautery was applied as necessary. It has been reported that the principle of thermal contraction can also be used to help correct trichiasis. Thermal contraction was applied to the pretarsal orbicularis oculi muscle attached to the low tarsal plate 4-5 mm below the lower lid margin[15].

The type of suture method, the failure to remove accurately redundant skin and orbicularis muscle, the lack of cilia rotational suture use, and excessive reverse growth of eyelashes are the main causes of failure and recurrence after epiblepharon correction in children.

Previous literature rarely reported the reasons for the failure and recurrence of the correction surgery of epiblepharon. As far as we know, this study is the first to analyze the causes of failure and recurrence of epiblepharon in children and to summarize the operation skills of reoperation.

Corrective surgery of epiblepharon in children often fails or there is recurrence. Reoperation is necessary due to obvious irritation symptoms and corneal injury. What are the causes? What should we pay attention to in reoperation?

To explore the causes of failure and recurrence after epiblepharon correction in children, and to observe the therapeutic effect after reoperation.

Twenty-two children (40 eyes) with epiblepharon were treated due to correction failure and recurrence. During reoperation, we accurately removed redundant epiblepharon and orbicularis muscle. Rotational suture technique and lid margin splitting were used.

After reoperation, all the patients were corrected. Photophobia, rubbing the eye, winking, and tearing disappeared. The corneal injuries were repaired. Follow-up observation for 6 mo showed no recurrence of epiblepharon.

The type of suture method, the failure to remove accurately redundant skin and orbicularis muscle, the lack of cilia rotational suture use, and excessive reverse growth of eyelashes are the main causes of failure and recurrence after epiblepharon correction in children.

In the future, more cases of recurrence of lower eyelid epiblepharon in children will be collected and will be followed up for a longer time after reoperation.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Bouvier A, Higuchi K, Yuki S S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Khwarg SI, Lee YJ. Epiblepharon of the lower eyelid: classification and association with astigmatism. Korean J Ophthalmol. 1997;11:111-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Woo KI, Yi K, Kim YD. Surgical correction for lower lid epiblepharon in Asians. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:1407-1410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sundar G, Young SM, Tara S, Tan AM, Amrith S. Epiblepharon in East asian patients: the singapore experience. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:184-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Noda S, Hayasaka S, Setogawa T. Epiblepharon with inverted eyelashes in Japanese children. I. Incidence and symptoms. Br J Ophthalmol. 1989;73:126-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kim NM, Jung JH, Choi HY. The effect of epiblepharon surgery on visual acuity and with-the-rule astigmatism in children. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2010;24:325-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Preechawai P, Amrith S, Wong I, Sundar G. Refractive changes in epiblepharon. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:835-839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yang SW, Choi WC, Kim SY. Refractive changes of congenital entropion and epiblepharon on surgical correction. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2001;15:32-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lee DC. Analysis of corneal real astigmatism and high order aberration changes that cause visual disturbances after lower eyelid epiblepharon repair surgery. Sci Rep. 2020;10:7498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tan MC, Young S, Amrith S, Sundar G. Epidemiology of oculoplastic conditions: the Singapore experience. Orbit. 2012;31:107-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hayasaka S, Noda S, Setogawa T. Epiblepharon with inverted eyelashes in Japanese children. II. Surgical repairs. Br J Ophthalmol. 1989;73:128-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Woo KI, Kim YD. Management of epiblepharon: state of the art. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2016;27:433-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Choo C. Correction of oriental epiblepharon by anterior lamellar reposition. Eye (Lond). 1996;10 (Pt 5):545-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kakizaki H, Selva D, Leibovitch I. Cilial entropion: surgical outcome with a new modification of the Hotz procedure. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:2224-2229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hwang SW, Khwarg SI, Kim JH, Kim NJ, Choung HK. Lid margin split in the surgical correction of epiblepharon. Acta Ophthalmol. 2008;86:87-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chang M, Lee TS, Yoo E, Baek S. Surgical correction for lower lid epiblepharon using thermal contraction of the tarsus and lower lid retractor without lash rotating sutures. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95:1675-1678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sokol JA, Thornton IL, Lee HB, Nunery WR. Modified frontalis suspension technique with review of large series. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;27:211-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ras AE, Hamed MH, Abdelalim AA. Montelukast combined with intranasal mometasone furoate versus intranasal mometasone furoate; a comparative study in treatment of adenoid hypertrophy. Am J Otolaryngol. 2020;41:102723. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Meyer CP, Lamp J, Vetterlein MW, Soave A, Engel O, Dahlem R, Fisch M, Kluth LA. Impact of Cardiovascular and Metabolic Risk Factors on Stricture Recurrence After Anterior One-stage Buccal Mucosal Graft Urethroplasty. Urology. 2020;Online ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sung Y, Lew H. Epiblepharon correction in Korean children based on the epicanthal pathology. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2019;257:821-826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Naik MN, Pujari A, Ali MJ, Kaliki S, Dave TV. Nonsurgical correction of epiblepharon using hyaluronic acid gel. J AAPOS 2018; 22: 179-182. e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kim MS, Sa HS, Lee JY. Surgical correction of epiblepharon using an epicanthal weakening procedure with lash rotating sutures. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98:120-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Asamura S, Nakao H, Kakizaki H, Isogai N. Is it truly necessary to add epicanthoplasty for correction of the epiblepharon? J Craniofac Surg. 2013;24:1137-1140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |