Published online Dec 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i23.6150

Peer-review started: June 30, 2020

First decision: August 21, 2020

Revised: September 2, 2020

Accepted: September 25, 2020

Article in press: September 25, 2020

Published online: December 6, 2020

Processing time: 153 Days and 19.3 Hours

Carotid body tumor (CBT) is a chemoreceptor tumor located in the carotid body, accounting for approximately 0.22% of head and neck tumors. Surgery is the main treatment method for the disease.

We reviewed the diagnosis and treatment of one patient who had postoperative secondary aggravation of obstructive sleep apnea–hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS) and hypoxia after surgical resection of bilateral CBTs. This patient was admitted, and relevant laboratory and imaging examinations, and polysomnography (PSG) were performed. After the definitive diagnosis, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) treatment was given, which achieved good efficacy.

This case suggested that aggravation of OSAHS and hypoxemia is possibly caused by the postoperative complications after bilateral CBTs, and diagnosis by PSG and CPAP treatment are helpful for this patient.

Core Tip: The case report provides analysis and summary of a patient who had postoperative secondary aggravation of obstructive sleep apnea–hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS) and hypoxia after bilateral carotid body tumor surgical. Our study suggested that continuous positive airway pressure treatment after manual pressure titration under polysomnography monitoring is effective in treating primary or secondary OSAHS.

- Citation: Yang X, He XG, Jiang DH, Feng C, Nie R. Postoperative secondary aggravation of obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome and hypoxemia with bilateral carotid body tumor: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(23): 6150-6157

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i23/6150.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i23.6150

Carotid body tumor (CBT) is a tumor derived from the carotid body, accounting for approximately 0.22% of the head and neck tumors[1]. CBT occurs mostly on the unilateral side. However, it can occur on bilateral sides in about 5% of the patients[2]. CBT is often closely related to the cervical sympathetic, glossopharyngeal, vagus, and hypoglossal nerves. Moreover, improper operation can result in severe damage to the craniocerebral nerves and blood vessels, leading to serious complications[3]. In 2016, a patient with secondary aggravation of obstructive sleep apnea–hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS) and hypoxemia after surgical resection of bilateral CBT underwent diagnosis and treatment in our department. The detailed report is as follows.

The patient reported snoring, apnea, labored breathing, occasional arousal, mental fatigue during the daytime, frequent hypersomnia, and inability to work.

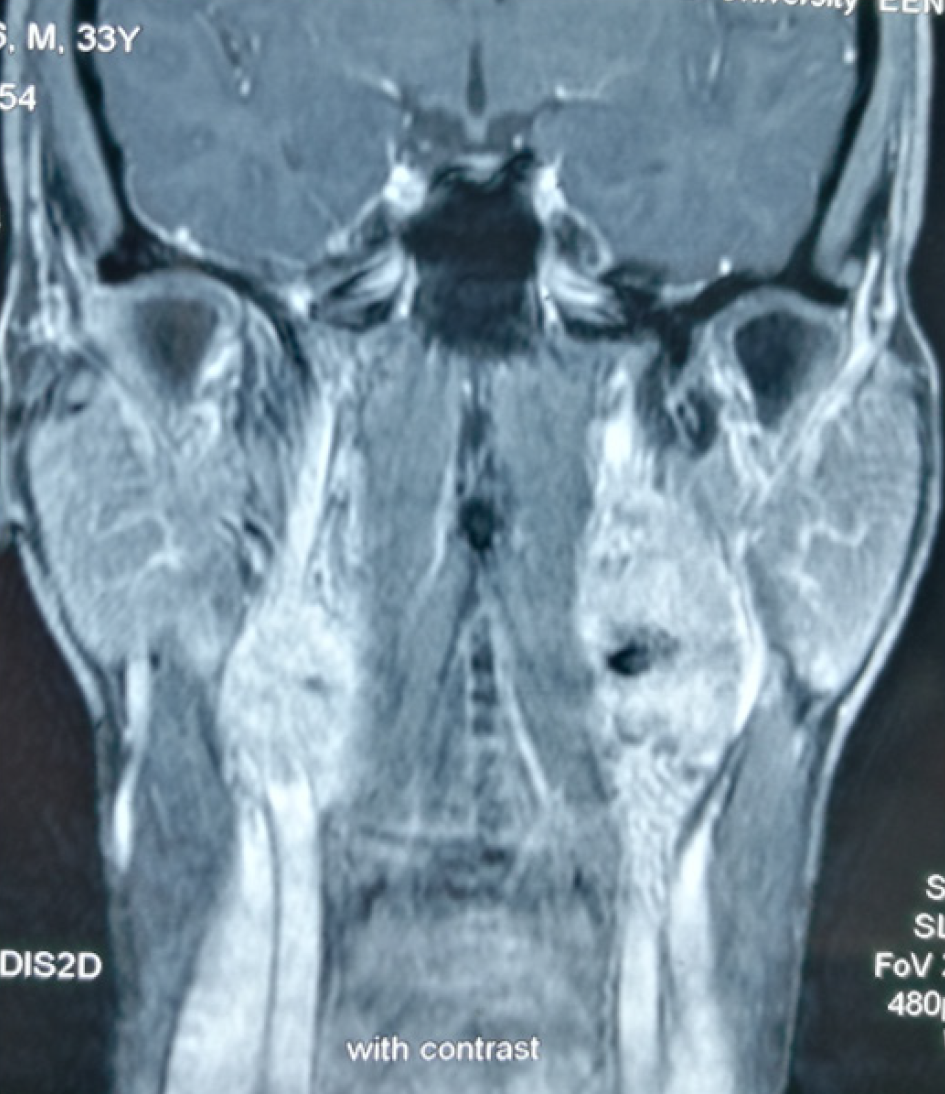

The patient reportedly had a headache, earache, and hearing loss in the left ear for 3 mo in 2016. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan revealed bilateral carotid aneurysms at our hospital (Figure 1). In December 2016, the patient underwent a resection of the right CBT at another institution in Shanghai, China. The surgery was successful with good postoperative recovery, and did not result in specific discomfort. In July 2017, the patient was readmitted to the same hospital and underwent a resection of the left CBT. On postoperative day 1, his extended tongue was left-deflected, and symptoms of dysphagia, bucking when drinking water, and hoarseness were reported. After 1 mo of treatment, the dysphagia and bucking when drinking water were alleviated, but symptoms of left deflection of extended tongue and hoarseness did not improve. At the same time, he self-reported the aggravation of symptoms of snoring and mouth breathing during sleep at night compared with those before surgery, which was accompanied by apnea, labored breathing, and occasional arousal. In September 2017, he presented to the Department of Respiratory Medicine and Neurology of our hospital, and the results of pulmonary function test and MRI of the head were unremarkable. In September 2017, due to dizziness and headache, he presented to the community hospital for physical examination, which suggested hypertension. His blood pressure reached as high as 205/100 mmHg. However, the patient had no previous or family history of hypertension. Nifedipine sustained-release tablets (20 mg bid) were orally administered, and his blood pressure fluctuated in the range of 140-160/90-100 mmHg. During this period, no treatment for snoring or apnea was given at home, and his symptoms progressively aggravated. He reported frequent arousal caused by labored breathing at night and was unable to fall asleep normally. Long-time apneas occurred three times at night (exceeding 2 min as described by his family members), and light coma for 30 min was reported. Following this, he was admitted to the community hospital for emergency treatment where he received oxygen inhalation. After positive-pressure ventilation with a balloon mask, the symptoms improved. However, the aforementioned symptoms occurred repeatedly. He reported mental fatigue during the daytime, frequent hypersomnia, and inability to work. Also, he had been unemployed. Since the onset of the first coma, the oxygen cylinder was available at home, and oxygen therapy (2-3 L/min) through a nasal catheter was given. After the occurrence of the aforementioned discomfort repeatedly for 2 mo, in November 2017, the patient presented to our hospital and was admitted to our department for treatment.

There was no previous history of hypertension or lung and cerebrovascular diseases. Previously, he had snoring and mouth breathing at night, but no apnea and arousal caused by labored breathing. He had a 10-year history of anxiety, mania, and insomnia aggravated after CBT surgery. Clinical features of the patient are showed in Table 1.

| A 39-year-old man, Han nationality |

| Basic data |

| Height, 168 cm; body weight, 86 kg; BMI, 30.4; blood pressure, 160/100 mmHg. No significant change in body weight occurred before and after the surgery |

| Symptoms |

| Snoring; apnea; labored breathing; occasional arousal; mental fatigue during the daytime; frequent hypersomnia; inability to work |

| Sign |

| Cyanotic lips; conjunctival congestion; mouth deviation to the left; and shallow nasolabial fold. The extended tongue was left-deflected. The tonsil was enlarged (grade I), and the body and base of the tongue and soft palate showed hypertrophy. The Friedman stage was type III. The muscle strength of the four limbs was normal. No dyspnea and three concave signs were noted. The Epworth hypersomnia scale (ESS) scored 21 points. The breath sounds of both lungs were clear, and the heart rhythm was regular. No pathological murmurs were heard |

| History of disease |

| No family history of CBT; No alcohol or tobacco; No previous history of hypertension or lung and cerebrovascular diseases. Previously, he had snoring and mouth breathing at night, but no apnea and arousal caused by labored breathing. He had a 10-yr history of anxiety, mania, and insomnia aggravated after CBT surgery |

| Drugs |

| Risperidone tablets (4 mg qd); sodium valproate (0.2 g bid); quetiapine (50 mg qd); and nifedipine sustained-release tablets (20 mg bid) |

The patient had no family history of CBT, and he had no habit of alcohol or tobacco.

He was 168 cm in height and weighed 86 kg with a body mass index of 30.4. His blood pressure was 160/100 mmHg. He reported no significant change in body weight before and after the surgery (Table 1).

Day 1: The pulmonary function test, blood test, and hepatorenal function test showed no abnormalities. Electronic laryngoscopy showed unobstructed throat, with the normal activity of the right vocal cord. The left vocal cord was fixed in the extended position. Continuous monitoring of oxygen saturation at night (23:00-07:00) was performed, and the lowest oxygen saturation (LSO2) was 45%.

Day 2: After admission, polysomnography (PSG) was performed by physicians at the sleep center of the nighttime department, and the results of sleep staging and respiratory events were determined according to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events[4]. The PSG results are shown in Table 2. At night, the patient self-reported difficulty in breathing, and oxygen inhalation with a mask at 3 L/min (2:00 am-7:00 am) was given, but PSG showed no significant improvement in apnea and hypoxemia.

| Polysomnography results | |

| Sleep date: Ratio of each sleep stage/TST | |

| T1 | 46.2% |

| T2 | 31.2% |

| T3 | 3.2% |

| REM | 19.4% |

| Apnea | |

| AHI | 22.3 times/h |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 106 times; Maximum duration, 192 s |

| Sleep microarousal index | 25.3 times/h |

| SpO2 | |

| Lowest awake SpO2 | 76% |

| Lowest sleep SpO2 | 36% |

| Total time of SpO2 below 90%/TST | 30.4% |

MRI of the head showed no abnormalities. Enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the cranial base and neck did not show the right CBT, and the residual lesion was seen on the left side, which was significantly smaller than that before the surgery.

Based on the aforementioned conditions, the physicians in the treatment group gave the diagnosis as follows: Bilateral CBT, OSAHS, hypoglossal, glossopharyngeal, and vagus nerve injuries, hypertension anxiety, and mania.

Sleep apnea and hypoxemia had seriously affected his life quality. Therefore, on the third and fourth days of admission, the automatic pressure titration of the bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP) was performed [90% time of average expiratory positive airway pressure (EPAP) was 8.5 cmH2O and 90% time of average inspiratory positive airway pressure (IPAP) was 13.5 cmH2O] with a ventilator under the monitoring of oxygen saturation at night. Simultaneously, consultation by psychiatrists was first performed for the assessment and diagnosis of the mental disease bipolar affective disorder, and medications were adjusted: Sodium valproate 0.4 g bid, escitalopram 10 mg qd, and quetiapine tablets 50 mg qd were administered. The results showed that the nocturnal hypoxia and apnea improved, and the patient reported a significant improvement in sleep quality. The patient did not experience arousal after labored breathing during sleep. In the morning, his mental state improved. However, a decrease in oxygen saturation was still observed at night, and the LSO2 was 69%. It was recommended that the patient continued to receive ventilator treatment or ventilator manual pressure titration. However, the patient had been unemployed for 1 year, and he refused further examination due to financial constraints.

On the fifth day after admission, he requested for discharge and continued to take oral psychotropic drugs and nifedipine sustained-release tablets (20 mg bid) after discharge. He bought a ventilator for treatment (BiPAP automatic pressure regulation mode; minimum EPAP 6 cmH2O and maximum IPAP 15 cmH2O) at home. The patient was advised to receive follow-up for 3-6 mo. Further, monitoring of blood pressure, follow-up medications, and the use of ventilator were recommended.

At the first follow-up in March 2018, the patient reported that symptoms of snoring, mouth breathing, apnea, and other symptoms at night had improved significantly, but labored breathing and arousal occasionally occurred at night. Sometimes he felt sleepy during the day, but hypersomnia had improved. The Epworth score was 11 points. He reported an improvement in physical strength and could afford daily housework. His blood pressure was 147/95 mmHg. No change in body weight was observed. Cyanosis in the lips was seen but was improved than earlier. Conjunctival congestion disappeared. The extended tongue was left-deflected, and the left deviation of the mouth had improved. The muscle strength of the four limbs was normal. The electronic laryngoscopy showed that the throat was unobstructed, and the activity of the right vocal cord was normal. The activity of the left vocal cord was improved but was still limited. The activity of the right vocal cord was compensated, and the hoarseness was improved. Imaging examination was not performed, so it was impossible to determine whether CBT recurred. He had a stable mental state. He continued taking psychotropic and antihypertensive drugs, and the usage and dosage were the same as earlier. He reported regular oral administration of antihypertensive drugs. He was advised to continue ventilator treatment in the same way as earlier.

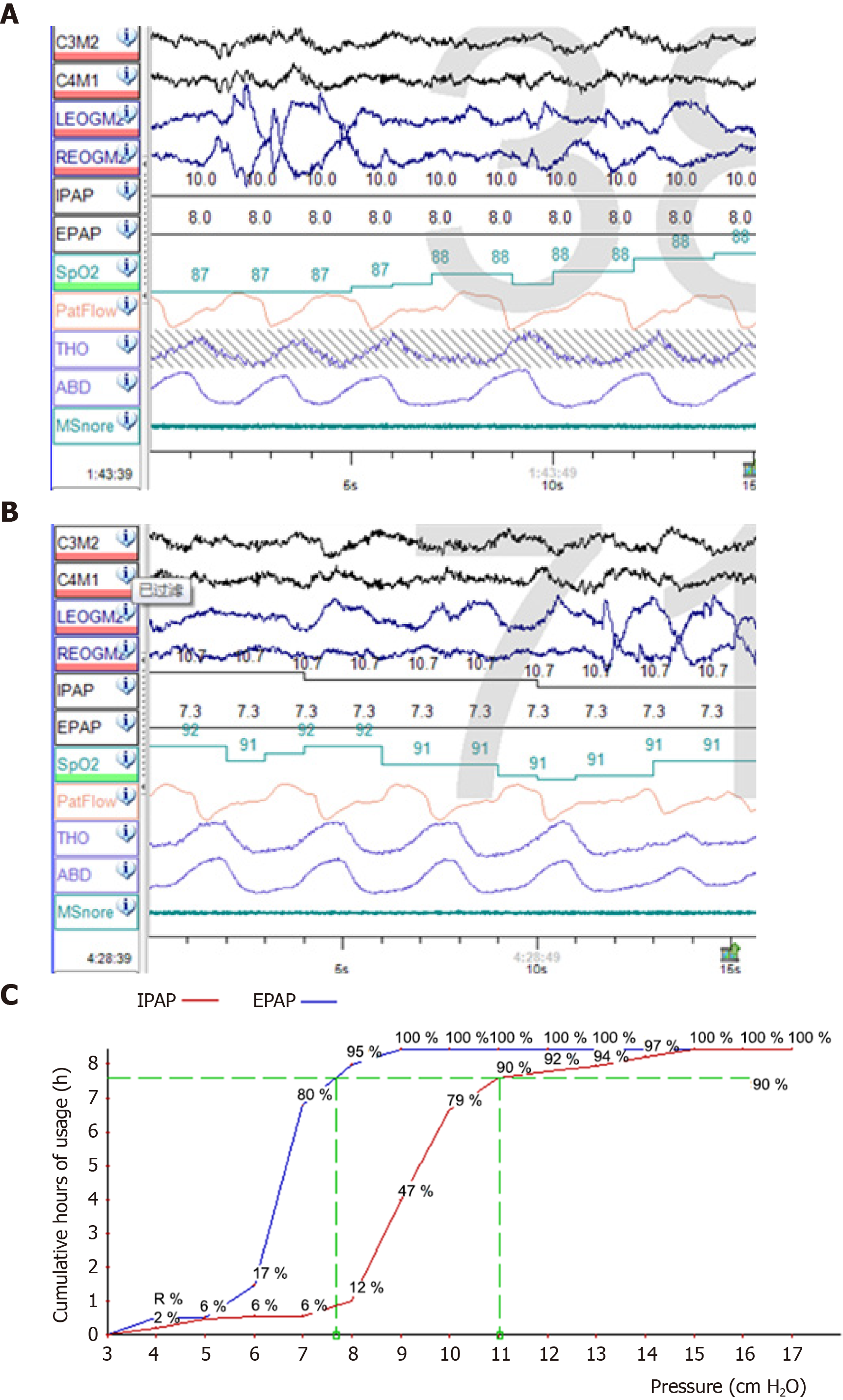

In June 2018, the follow-up was performed again, and the patient’s chief complaints were similar to those 3 mo earlier. Given the injury of the carotid body chemoreceptor after bilateral CBT surgery, prompt feedback was impossible to regulate breathing, and carbon dioxide (CO2) retention and hypoxemia still occurred at night. The ventilator manual pressure titration was recommended. The patient was readmitted to the hospital to undergo manual pressure titration of PSG, and the titration technique referred to the AASM guidelines for pressure titration[5]. The results showed that the ratio of each sleep stage (T1, T2, T3, and REM period)/TST was 25.4%, 44.6%, 13.6%, and 16.4%, respectively. The sleep apnea/hypopnea index was 2.6 times/h. PSG and titration results are shown in Figure 2. The patient was advised to continue ventilator treatment (BiPAP fixed pressure mode EPAP 7.5 cmH2O and IPAP 11 cmH2O) and low-flow oxygen inhalation at 1 L/min at night.

In November 2018, the patient was followed again. He reported a marked improvement in sleep quality at night, daytime physical strength, and energy. He could complete physical activities such as 2-km jogging or mountain climbing. He had found a new job, achieved certain economic status, and was satisfied with the therapeutic effect of the ventilator. He presented to the psychiatry department and reported adjustment of the use of psychotropic drugs, and the drugs were reduced as appropriate: Sodium valproate 0.4 g qd and quetiapine 50 mg qd. One month earlier, the dose of antihypertensive drugs was reduced by himself: Nifedipine sustained-release tablets 20 mg qd. His blood pressure was 137/85 mmHg; cyanosis of lips had disappeared, and the extended tongue was still left-deflected. The Epworth score was 6 points. In January 2019, the patient was followed again. He had no specific discomfort. CT of the neck and skull base was performed, showing that the space-occupying lesion on the left neck was enlarged than earlier, which was suspicious of the recurrence of the left CBT. However, the patient was worried about the postoperative complications and refused to undergo surgery again. Oral administration of psychotropic and antihypertensive drugs and ventilator treatment were continued, with the same therapeutic regime as that 3 mo ago.

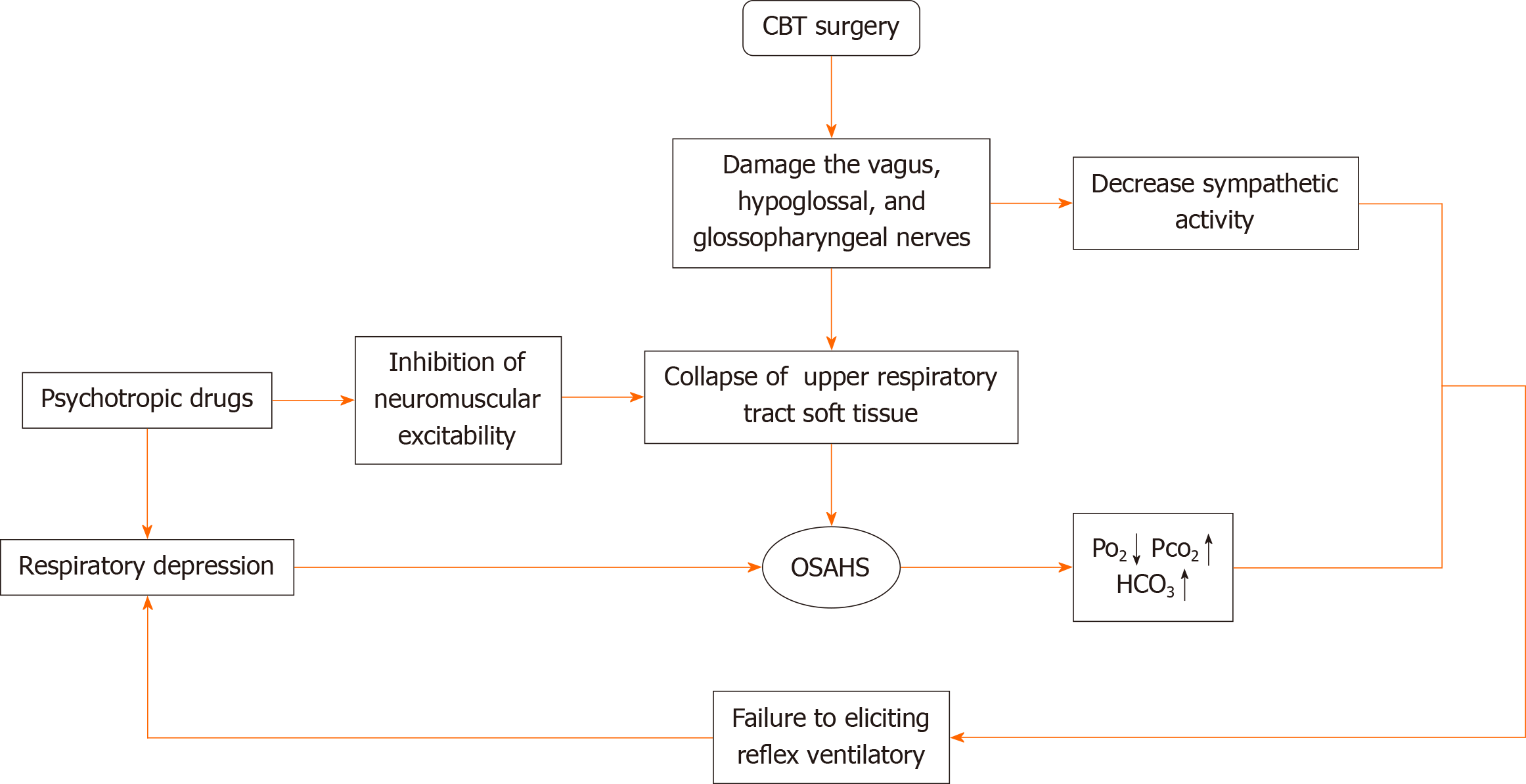

The carotid body is the main chemoreceptor, which senses changes in arterial blood oxygen concentration and plays an important role in regulating the body under stress response in a hypoxic environment. The greater the CBT tumor, the higher the likelihood of damage to the vagus, hypoglossal, and glossopharyngeal nerves[6]. After analysis of the patient’s clinical data, we speculated that the secondary aggravation of OSAHS and hypoxemia after CBT surgery might be due to the following reasons (Figure 3).

After the resection of bilateral CBT, the left hypoglossal, glossopharyngeal, and vagus nerves were injured, and the muscle tone in the root of the tongue and throat decreased. Thus, the collapse of soft tissues of the upper respiratory tract during sleep could easily occur, causing airway obstruction and exacerbating OSAHS and hypoxemia.

The oral administration of psychotropic drugs before admission caused sedation, hypersomnia, and central respiratory depression, thereby exacerbating OSAHS and hypoxemia. On the contrary, continual apnea and hypoxemia during night and fatigue during the daytime caused by OSAHS might aggravate the patient’s mental disorder, such as hypersomnia, anxiety, and mania.

The carotid body is innervated by the anterior segment of the sympathetic nerve, the glossopharynx, and the vagus nerve. When the carotid body detects decreasing levels of oxygen (hypoxia), increasing levels of CO2 (hypercapnia), and decreasing pH (acidosis), it increases the respiratory rate, tidal volume, heart rate, and blood pressure together with vasoconstriction[7]. After bilateral CBT surgery, due to the injury of nerves and carotid body, the body’s sensitivity to timely feedback to regulate respiratory movement was decreased, which destroyed the rhythm and timeliness of the body’s autonomous respiration, thus leading to the time extension of apnea, which aggravated nocturnal hypoxemia and CO2 retention.

OSAHS and hypoxemia could seriously affect the life quality of the patient. Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) has become the preferred treatment method for OSAHS, especially for adult patients. The traditional CPAP manual pressure titration is mostly completed under the guidance of PSG, and the treatment process is time-consuming. Also, the medical expenses are high. Therefore, in this case, the automatic pressure titration was first used under the monitoring of oxygen saturation, and the patient’s condition was alleviated but the best efficacy was still not achieved. Some studies suggested that automatic titration, as well as manual titration, could determine the optimal CPAP treatment pressure, but its effectiveness and safety remain controversial[8]. In this patient, due to the complication after CBT surgery, the collapse of soft tissues of the upper respiratory tract persisted during inspiratory and expiratory breathing. CPAP treatment needs accurate and stable EPAP and IPAP pressure. Using PSG-monitored manual pressure titration, a more accurate ventilator treatment prescription was given, achieving satisfactory effects and improving his life quality.

In the meantime, due to the improvement in nighttime sleep quality and respiratory disorders, his hypertension and mental disease were also relieved. In recent years, numerous studies have shown that OSAHS is closely associated with arteriosclerosis and refractory hypertension[9].The patient’s blood pressure was elevated and tended to be stable after medication and CPAP, which also confirmed the aforementioned ideas.

Bilateral CBT is clinically rare, and the likelihood of injuries to the cervical large vessels and cranial nerves during surgery is high. The analysis and summary of the case discussed in this study suggested that the possible secondary OSAHS and hypoxemia were caused by complications after unilateral or bilateral CBT surgery. CPAP treatment after manual pressure titration under PSG monitoring was effective in treating the primary or secondary OSAHS. Also, physicians at related departments deepened their understanding of CBT and OSAHS during the diagnosis of this patient and learned and improved the techniques of PSG and pressure titration.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Li SC, Yoshimoto S S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Asanuma K, Sugenoya A, Takemae T, Kobayashi S, Nomura S, Itoh N, Iida F. The safe and complete removal of a carotid body tumor with elements suggestive of a malignant potential by employing an intraluminal shunt: report of a case. Surg Today. 1995;25:155-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Parry DM, Li FP, Strong LC, Carney JA, Schottenfeld D, Reimer RR, Grufferman S. Carotid body tumors in humans: genetics and epidemiology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1982;68:573-578. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Knight TT Jr, Gonzalez JA, Rary JM, Rush DS. Current concepts for the surgical management of carotid body tumor. Am J Surg. 2006;191:104-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Berrry R, Brooks R, Gamaldo C, Haiding S, Lloyd R, Marcus C, Vaughn B. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications. 2016; version 2.3. Available from: https://aasm.org/clinical-resources/scoring-manual/. |

| 5. | Kushida CA, Chediak A, Berry RB, Brown LK, Gozal D, Iber C, Parthasarathy S, Quan SF, Rowley JA; Positive Airway Pressure Titration Task Force; American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Clinical guidelines for the manual titration of positive airway pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4:157-171. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Luna-Ortiz K, Rascon-Ortiz M, Villavicencio-Valencia V, Herrera-Gomez A. Does Shamblin's classification predict postoperative morbidity in carotid body tumors? Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;263:171-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Trasande L, Chatterjee S. The impact of obesity on health service utilization and costs in childhood. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009;17:1749-1754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Luo J, Xiao S, Qiu Z, Song N, Luo Y. Comparison of manual versus automatic continuous positive airway pressure titration and the development of a predictive equation for therapeutic continuous positive airway pressure in Chinese patients with obstructive sleep apnoea. Respirology. 2013;18:528-533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Khan A, Patel NK, O'Hearn DJ, Khan S. Resistant hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea. Int J Hypertens. 2013;2013:193010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |