Published online Dec 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i23.6064

Peer-review started: July 13, 2020

First decision: August 22, 2020

Revised: September 4, 2020

Accepted: October 27, 2020

Article in press: October 27, 2020

Published online: December 6, 2020

Processing time: 144 Days and 6.4 Hours

Novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was first found in Wuhan, China, and it has rapidly spread worldwide since the end of 2019. There is an urgent need to treat the physical and psychological aspects of COVID-19. Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT)-based psychological intervention is an evidence-based therapy for depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.

This report describes a case of COVID-19 in a patient who transmitted the disease to his entire family. The patient received four sessions of IPT-based psychological intervention. We used the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression and Patient Health Questionnaire to measure depression level, and the Hamilton Anxiety Scale and Generalized Anxiety Disorder to measure anxiety among the patients.

This case shows that IPT-based therapy can reduce COVID-19 patient depression and anxiety and the advantage of IPT-based therapy.

Core Tip: Coronavirus disease 2019 has induced negative emotions (COVID-19), such as anxiety, depression, insomnia, denial, anger, fear, and stress, that affect medical staff, patients, and the general public. Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT)-based psychological intervention is an evidence-based therapy for depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. We found that interpersonal IPT-based therapy is efficacious in COVID-19 patients with these psychological problems.

- Citation: Hu CC, Huang JW, Wei N, Hu SH, Hu JB, Li SG, Lai JB, Huang ML, Wang DD, Chen JK, Zhou XY, Wang Z, Xu Y. Interpersonal psychotherapy-based psychological intervention for patient suffering from COVID-19: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(23): 6064-6070

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i23/6064.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i23.6064

At the end of 2019, a new strain of human coronavirus emerged in Wuhan, China and has since spread worldwide. This disease is now known as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). COVID-19 is a major public health concern because little is known about the virus, and it causes serious damage to the lungs and may be fatal. The experience with severe acute respiratory syndrome showed that severe epidemics can bring psychological as well as physical trauma. During quarantine, patients with COVID-19 cannot see their families and friends, which contributes to their fear and loneliness and may reduce the effectiveness of their treatment. COVID-19 has induced negative emotions, such as anxiety, depression, insomnia, denial, anger, fear, and stress, that affect medical staff, patients, and the general public at different levels[1-3].

Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) is a time-limited method of psychotherapy. It was originally developed for the treatment of depression. Later, it was applied to other mental and associated diseases by focusing on patients’ social and interpersonal functions[4-6]. IPT was developed by Klerman and Weissman[7,8] in the 1980s and originated from theories of sociology, attachment, and communication. Based on the interpersonal theories of Sullivan[4] and Meyer[9] and several empirical studies, interpersonal stress is connected with the onset of depression. IPT focuses on relationships and is based on the theory that personal relationships play a key role in psychological problems. Even if relationships are not the cause of psychological problems, psychological problems can and may affect relationships and create new problems that are associated with interpersonal communication. As a result, we can alleviate psychological problems by improving interpersonal communication. By focusing on the current situation instead of searching for subconscious origins and looking at how more immediate difficulties contribute to the symptoms, IPT works in many areas such as grief, interpersonal disputes, psychological dysfunction due to life transitions, social isolation, and social deficits via techniques of interpersonal adjustment. The success of IPT in a series of randomized clinical trials has led to treatment of a variety of subtypes of depression and other psychiatric syndromes[9]. IPT also has effectiveness in treating social anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), eating disorders, and bipolar disorder.

In the COVID-19 pandemic, IPT has shown some advantages. First, the acute form of IPT, which is 12-16 wk of treatment, is a focused, practical, and proven time-limited form of psychotherapy. There are some benefits to this, such as fitting the timeline of the quarantine and saving money for the patients. Second, compared with other therapists, IPT therapists are more active and non-neutral. The treatment is time-limited, and as a result, the therapists need to be more efficient. IPT therapists play an active role during treatment with a focus on the problem area and implementation of interventional skills, such as practical suggestions, role-play, and psychoeducation. Third, IPT focuses on current symptoms and recent relationships and life events. IPT uses a medical model on psychiatric illness, seeing that the symptoms are caused by the disease instead of the patients’ themselves, to prevent the patients from feeling frustrated or guilty for their emotional or mental disorders. Fourth, IPT is always linked to mood and events and links the symptoms to specific interpersonal problems.

In the present case, most symptoms arose from the family, so IPT was well suited. This report describes four sessions of IPT-based psychological intervention in a patient who infected his entire family with COVID-19.

The patient presented with fever and cough for 5 d.

The patient is a doctor employed in a rural clinic in Henan Province. During the explosive period of the COVID-19 outbreak, many people came to him for treatment. At the end of January 2020, he started to have a fever and sore throat. As a doctor, he suspected that he might have COVID-19, so he went to a local hospital for help. However, at that time, diagnosis and treatment measures were still immature, and he was advised to return home and isolate himself. As the information about COVID-19 became clearer, the patient was more convinced of his judgment. He knew that The First Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University was good at handling infectious diseases, so he drove his family to Hangzhou. If his diagnosis was confirmed, his wife and daughter would also have been at risk.

When he and his family arrived at the hospital, they were all confirmed to have COVID-19 and were hospitalized in the isolation ward. It was considered that the family could care of each other; therefore, they stayed together in a single room. However, family problems soon arose. The patient’s wife complained that he brought the virus home and transmitted it to their daughter. The daughter was adolescent and rebellious. She was dissatisfied with staying with her parents all day in the isolation ward. All this resulted in the patient feeling guilty. Later, he developed insomnia, was unhappy, and always wanted to cry. His guilt for the family led to a feeling of failure.

The doctors in The First Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University decided that the patient needed help with these symptoms, so they contacted a psychiatrist at the hospital. The psychiatrist made an initial assessment of the patient’s symptoms using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder questionnaire (GAD-7) to assess his level of anxiety and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) to assess his level of depression. The GAD-7 score was 20 and the PHQ-9 score was 21, which showed that he had severe anxiety and depression. Although depression cannot be diagnosed by time-based diagnostic criteria, intervention for stress was urgently needed.

The patient was in good health with no comorbidities.

Neurological examination was normal.

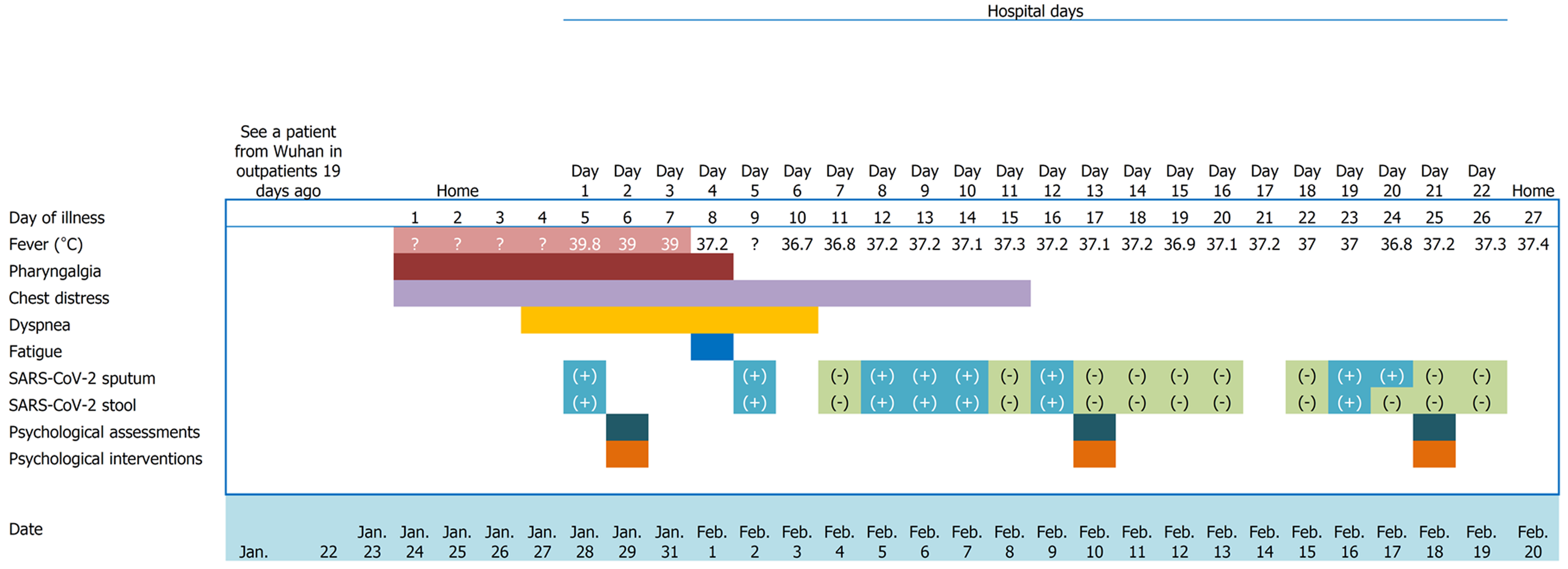

The main results are showed in Figure 1 in the part of treatment.

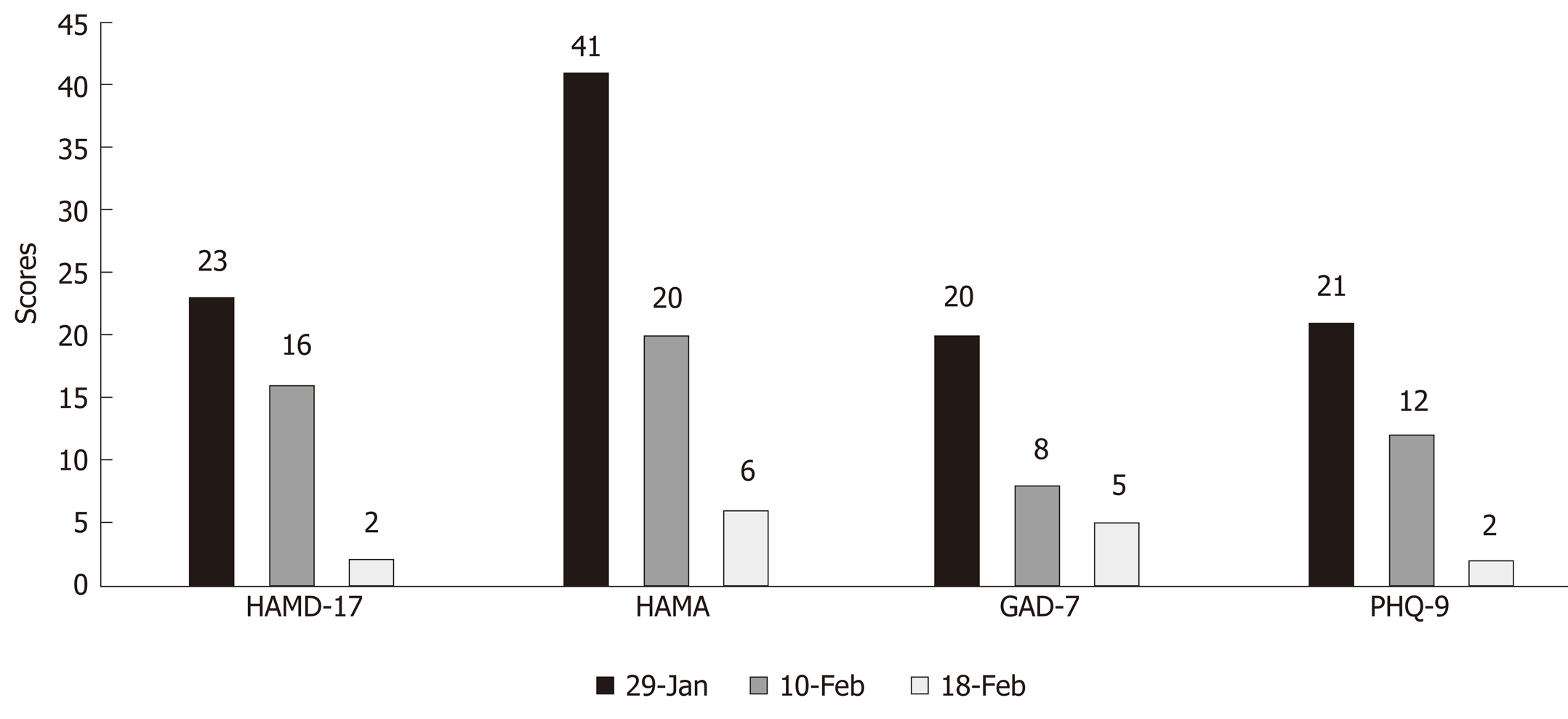

An independent psychoanalysist arranged a series of evaluations to test the patient’s level of depression and anxiety before, at the middle, and after treatment with the Hamilton Rating Scale (HAMD-17), Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAMA), GAD-7, and PHQ-9. The results are shown in Figure 2. The first assessment was taken on January 29th. The scores of HAMD-17, HAMA, GAD-7, and PHQ-9 were 23, 41, 20, and 21, respectively. Then he had 1 wk of psychotherapy using the IPT technique. After the first session of the therapy, the scores of the HAMD-17, HAMA, GAD-7, and PHQ-9 were 16, 20, 8, and 12, respectively. After another session of therapy (which lasted for 1 wk), his last scores of the HAMD-17, HAMA, GAD-7, and PHQ-9 were 2, 6, 5, and 2, respectively. Afterwards he did not have any further therapy for his psychological problems.

The final diagnosis was COVID-19.

Considering that the patient’s situation was mainly caused by the specific circumstances and his relationship with his family, the psychotherapist selected IPT to treat the patient’s psychological symptoms after talking with the clinician. IPT is time limited and change-oriented and aims to change interpersonal relationships to improve patients’ mental state. The psychotherapist knew that the patient’s antiviral therapy was imminent and that the IPT had to fit with that timeline. After discussion with the patient, the therapist proposed three IPT sessions in total. After IPT, the patient’s mood was significantly improved.

The first session was on January 29, 2020. The psychotherapist encouraged the patient to talk about anything that disturbed him in order to release intense emotions. The main techniques used in this session were nonjudgmental listening and empathy. After the patient reached a more stable state, psychoeducation was involved, giving the patient the “sick role.” The therapist told the patient that although his emotional problems were not included in the diagnostic criteria, they were serious. The psychotherapist believed that the patient’s current condition was mainly due to his emotional disorders that came from his family relationships. In turn, those bad relationships led to new problems with his family members. The method of breaking this vicious cycle was changing his relationship with his family to be more open. The patient talked a lot about the relationship between himself and his family members. He described the relationship in the pie chart. He felt that he had nobody to talk to and the closest people in his life were opposed to him. He felt guilt towards his family because he had brought COVID-19 into the home. The patient agreed with the therapist that if he could deal with the relationship with his family members, his psychological problems would be generally resolved. The therapist guided the patient to choose a problem area that he felt was dominant. The patient thought he was suffering from interpersonal dispute and role transition. The therapist agreed to choose interpersonal disputes as the main problem area, as the patient’s emotional problems mainly came from family members’ dissatisfaction and complaints as well as his guilt. At the end of this session, the patient felt better.

The second session was on February 10, 2020. At the beginning of the session, the patient shared with the therapist that he felt better immediately after the first session was finished, but when he went back to his family, the communication still disturbed him. The therapist suggested that the patient talk more about the communication among the family members. The patient pointed out that his wife knew he had emotional problems. Sometimes she would restrain herself, but she was still unhappy with the patient and 1 d shouted at him. His daughter always upset him as she felt that her father had ruined her life, and she was eager to go out to play with her friends. She once claimed that she should have depression instead of him. The therapist tried to inspire the patient to establish a new way to communicate with his family. Later, the patient realized that he was always serious in the family and never showed his feelings or emotions. He thought that he should talk more about his feelings and show more expression. At the end of the second session, the patient said he would try some new ways of communication, and he had a new idea of the relationship pie chart, his wife may stay in the central of the relationship pie chart.

The third session was on February 18, 2020. The patient was happy because the doctor told him that he could be discharged on the next day. He appreciated the therapist’s suggestion of changing communication style. In fact, he had seldom communicated with his wife and daughter in his family. He went back to the room and thought about the pie chart of interpersonal relationships and considered that maybe it was an opportunity for him to change something about his family. He raised a conversation among the three family members. His wife pointed out that she was actually dissatisfied with their marriage. She was unable to communicate emotionally with her husband. Her adolescent daughter had always troubled her a lot, but she could not get help and support from her husband. She was angry about her marriage. Moreover, the daughter thought her father was always absent during her lifetime. She felt uncomfortable with the first time of close contact with her father in this way. She felt fear and anger. The therapist reminded the patient that interpersonal relationships influenced the emotions a lot and keeping good relationships can be a support in any type of crisis. Communication style affects relationships, and if we are unable to achieve what we want from our relationships, we should consider that something may be wrong with our communication. The patient agreed with the therapist, promised to improve his skills, and deal with the communication problems in his family. At the end, the therapist summarized the three sessions, and said goodbye to the patient and his family.

The depression and anxiety in this patient with COVID-19 were improved after the IPT-based therapy.

IPT benefits patients who are suffering from PTSD as well as depression. IPT is based on interpersonal theories and has been effective under controlled research conditions to treat a variety of disorders. Two large randomized controlled trials showed that IPT can produce improvement among people with major depression[10,11]. The fact is that many patients who suffer from depression believe that interpersonal problems contributed to the onset of their illness. IPT has also been used for treatment of other comorbid disorders[9]. Bleiberg et al[12] developed a model of individual IPT for PTSD that yielded improvement in symptoms. A United States National Institute of Mental Health-funded and randomized controlled study compared different treatments for PTSD and demonstrated the efficacy of IPT[13,14].

The present case report demonstrated the use of IPT-based psychological intervention for a patient with COVID-19, whose problems were mainly caused by family interpersonal relationships. GAD-7, PHQ-9, HAMD-17, and HAMA were used to assess improvement of symptoms and showed the effectiveness of IPT-based psychological intervention. The evidence-based IPT worked in this case through three sessions. Treatment of COVID-19 usually does not take long, and the patient’s mood during the process had an impact on treatment of physical diseases. When patients feel helpless, in some extreme cases, they even think of suicide, and we need to provide timely psychological intervention for those patients. IPT is time limited and was found to be a good choice in patients with COVID-19.

As COVID-19 has spread around the world, it has led to a psychological crisis, and psychological intervention is needed urgently. Patients, families, and medical staff are all at the risk of developing psychological problems.

Not all crises lead to PTSD. Although many factors are involved in PTSD, some researchers have proposed that the interpersonal features may influence the onset, chronicity, and treatment of PTSD[14,15]. IPT supposes that interpersonal relationships are affected by crises, and problems related to interpersonal relationships exacerbate the problems. IPT deals with problem areas: Grief or complicated bereavement, interpersonal conflicts, role transition, and interpersonal deficits[16,17]. In the present case, the problem area was interpersonal conflicts, and he benefited from IPT within a few weeks. This case reminds us that IPT is efficacious and has advantages of being time limited, the therapists are active and non-neutral, have a current focus, and investigate the link between mood and events. IPT provides rapid, relationship-based, short-term therapy.

Some studies have shown that the onset of COVID-19 may affect neurological symptoms[18]; however in this case, no neurological disease or symptoms were found. IPT is effective in this case, but it is still unknown whether it is able to be extended to patients with neurological disorders. Although during the epidemic period, we also adopted a lot of online remote intervention methods, in this case, it is still that the doctor interviewed the patient face-to-face with a set of isolation clothes for the doctor. As a result, however, we may have neglected whether wearing isolation clothes will affect the therapy in the emergency. This gives us the idea that in the future we can ask the patients about the feeling of conversing with a psychotherapist wearing isolation clothes[19].

There was a decrease in the assessment scores after therapy, which shows that IPT-based therapy can reduce COVID-19 patient depression and anxiety. This report also demonstrated the effectiveness and advantage of IPT-based therapy in COVID-19 patients.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D, D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Montemurro N, Shrestha B, Wang YP S-Editor: Huang P L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Kang L, Li Y, Hu S, Chen M, Yang C, Yang BX, Wang Y, Hu J, Lai J, Ma X, Chen J, Guan L, Wang G, Ma H, Liu Z. The mental health of medical workers in Wuhan, China dealing with the 2019 novel coronavirus. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:e14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1321] [Cited by in RCA: 1060] [Article Influence: 212.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Liu S, Yang L, Zhang C, Xiang YT, Liu Z, Hu S, Zhang B. Online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:e17-e18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1118] [Cited by in RCA: 1088] [Article Influence: 217.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Montemurro N. The emotional impact of COVID-19: From medical staff to common people. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:23-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 332] [Cited by in RCA: 269] [Article Influence: 53.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Evans FB. Interpersonal Theory of Psychiatry (Sullivan). In: Zeigler-Hill V, Shackelford T. (eds) Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences. Springer, Cham, 2017. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss. 2nd ed, Vol. 1: Attachment. New York: Basic Books, 1969. |

| 6. | Weissman MM, Markowitz JC, Herman GL. Comprehensive guide to interpersonal psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books, 2000. |

| 7. | Henderson AS, Byrne DG, Duncan-Jones P. Neurosis and the social environment. Sydney, Australia: Academic Press, 1981. |

| 8. | Kiesler DJ. Contemporary Interpersonal Theory and Research: Personality, Psychopathology, and Psychotherapy. J Psychother Pract Res. 1997;6:339-341. |

| 9. | Weissman MM, Markowitz JC, Herman GL. Comprehensive guide to interpersonal psychotherapy (In Chinese). Hangzhou: Zhejiang Gongshang University Press, 2018. |

| 10. | DiMascio A, Weissman MM, Prusoff BA, Neu C, Zwilling M, Klerman GL. Differential symptom reduction by drugs and psychotherapy in acute depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1979;36:1450-1456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Swartz HA, Grote NK, Graham P. Brief Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT-B): Overview and Review of Evidence. Am J Psychother. 2014;68:443-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bleiberg KL, Markowitz JC. A pilot study of interpersonal psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:181-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Foa EB, Rothbaum BO. Treating the Trauma of Rape: Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for PTSD. New York: The Guilford Press, 1998. |

| 14. | Markowitz JC, Milrod B, Bleiberg K, Marshall RD. Interpersonal factors in understanding and treating posttraumatic stress disorder. J Psychiatr Pract. 2009;15:133-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Swartz HA, Frank E, Shear MK, Thase ME, Fleming MA, Scott J. A pilot study of brief interpersonal psychotherapy for depression among women. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:448-450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Miranda J, Chung JY, Green BL, Krupnick J, Siddique J, Revicki DA, Belin T. Treating depression in predominantly low-income young minority women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:57-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 342] [Cited by in RCA: 340] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | O'Hara MW, Stuart S, Gorman LL, Wenzel A. Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:1039-1045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 453] [Cited by in RCA: 376] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Di Carlo DT, Montemurro N, Petrella G, Siciliano G, Ceravolo R, Perrini P. Exploring the clinical association between neurological symptoms and COVID-19 pandemic outbreak: a systematic review of current literature. J Neurol. 2020;1:1–9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Montemurro N, Perrini P. Will COVID-19 change neurosurgical clinical practice? Br J Neurosurg. 2020;1-2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |