Published online Dec 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i23.6056

Peer-review started: June 12, 2020

First decision: September 13, 2020

Revised: September 27, 2020

Accepted: October 13, 2020

Article in press: October 13, 2020

Published online: December 6, 2020

Processing time: 174 Days and 24 Hours

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an emerging infectious disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Suspected cases accounted for a large proportion in the early stage of the COVID-19 outbreak. The deviation of the nucleic acid test by throat swab (the current gold standard of COVID-19) caused by variation in sampling techniques and reagent kits and coupled with nonspecific clinical manifestations make confirmation of the suspected cases difficult. Proper management of the suspected cases of COVID-19 is crucial for disease control.

A 65-year-old male presented with fever, lymphopenia, and chest computed tomography (CT) images similar to COVID-19 after percutaneous coronary intervention. The patient was diagnosed as having bacterial pneumonia with cardiogenic pulmonary edema instead of COVID-19. This was based on four negative results for throat swab detection of SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid using reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction assay and one negative result for serological antibody of SARS-CoV-2 with the serological assay. Additionally, the distribution of ground-glass opacities and thickened blood vessels from the CT images differed from COVID-19 features, which further supported the exclusion of COVID-19.

Distinguishing COVID-19 patients from those with bacterial pneumonia with cardiogenic pulmonary edema can be difficult. Therefore, it requires serious identification.

Core Tip: A 65-year-old male presented with fever, lymphopenia, and similar computed tomography (CT) findings of coronavirus disease 2019 after percutaneous coronary intervention. The patient was diagnosed with bacterial pneumonia with cardiogenic pulmonary edema following the negative results from the nucleic acid test and serological detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, ground-glass opacities mainly in parahilar regions from the CT images, and treatment response. This report suggested that serious identification is required to distinguish COVID-19 and common pneumonia.

- Citation: Gong JR, Yang JS, He YW, Yu KH, Liu J, Sun RL. Suspected SARS-CoV-2 infection with fever and coronary heart disease: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(23): 6056-6063

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i23/6056.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i23.6056

In December 2019, a novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) emerged in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China[1]. It spread quickly to other provinces of China and overseas[2]. A total of 59804 confirmed cases, 1365 death, and 13435 suspected cases were reported in China by February 12, 2020[3]. A “suspected case” is defined as a patient with epidemiological history with any two clinical features [fever or respiratory symptoms, leukopenia or lymphopenia, chest imaging of patchy shadows or ground-glass opacities (GGO)] or having no epidemiological history but with the above three clinical manifestations[4]. However, these symptoms (like fever, cough, etc.) are not unique because they are found in many other infectious diseases. In addition, lymphopenia could be seen in patients with an impaired immune system. The deviation of the nucleic acid test by throat swab (the current gold standard of COVID-19) caused by variation in sampling techniques and reagent kits and coupled with nonspecific clinical manifestations make confirmation of the suspected cases difficult. Management of the suspected cases during the epidemic period prevents further spread and preserves healthcare resources. Here, we present the diagnosis and treatment of a suspected case of COVID-19 during the epidemic period.

A 65-year-old man was admitted to the cardiovascular internal medicine department with chest pain for 9 d. He presented with fever, cough, and chest tightness after percutaneous coronary intervention for 4 d.

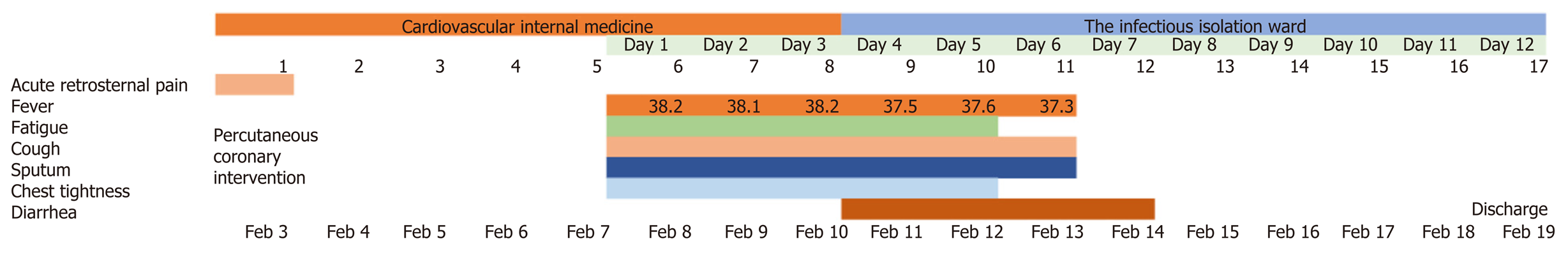

Acute retrosternal pain occurred in the patient 9 d ago. An emergency percutaneous coronary intervention therapy was performed on the patient due to the abnormally elevated levels of troponin and ST-segment when presented at the cardiovascular internal medicine department that day. The patient had suffered a transient loss of consciousness due to ventricular fibrillation after percutaneous coronary intervention. Four days ago, the patient incurred fever, cough with white sticky sputum, and chest tightness. Moreover, the patient had a maximum body temperature of 38.2 °C and chest computed tomography (CT) images that were similar to COVID-19. The patient was therefore transferred to the infectious isolation ward with a possible diagnosis of COVID-19 on the 4th d of fever onset (Figure 1).

The patient’s medical history included hypertension, lacunar infarction, and history of aortic aneurysm surgery.

He had no history of living in Wuhan, the epidemic area, or exposure to patients with COVID-19. Social history was negative for tobacco, alcohol, or substance abuse. No obvious family history.

The temperature was 37.5 °C, heart rate 80 bpm, respiratory rate 21 bpm, blood pressure 112/72 mmHg, and oxygen saturation was 96%. The patient had harsh breath sounds and scattered moist rales during auscultation of both lower lungs. We considered this to be either lung inflammation or heart failure. The cardiac and digestive portions did not show abnormalities.

Blood analysis showed lymphopenia was 0.76 × 109/L, elevated neutrophils count: 6.8 × 109/L (normal range < 6.4 × 109/L), normal white blood cell count, and normal hematocrit and platelet count. Routine stool and urine test results were normal. Biochemical assessment of the blood demonstrated normal liver and kidney function but increased levels of hypersensitive troponin I: 1.64 ng/mL (normal range < 0.12 ng/mL) and N-terminal pronatriuretic peptide: 2860 pg/mL (normal range < 125 pg/mL). There was an increase in C-reactive protein (CRP): 114.6 mg/L (normal range < 8 mg/L), procalcitonin (PCT): 0.26 ng/mL (normal range < 0.05 ng/mL), and D-dimers: 3.32 μg/mL (normal range < 0.5 μg/mL). CD3, CD4, and CD8 T-lymphocyte counts declined simultaneously. Two real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR results for the SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid tests by throat swab were negative. Electrocardiogram revealed the acute anterior and inferior myocardial infarction. Two-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography revealed ultrasound changes of acute myocardial infarction, a cardiac ejection fraction of 35%, and mild pulmonary hypertension.

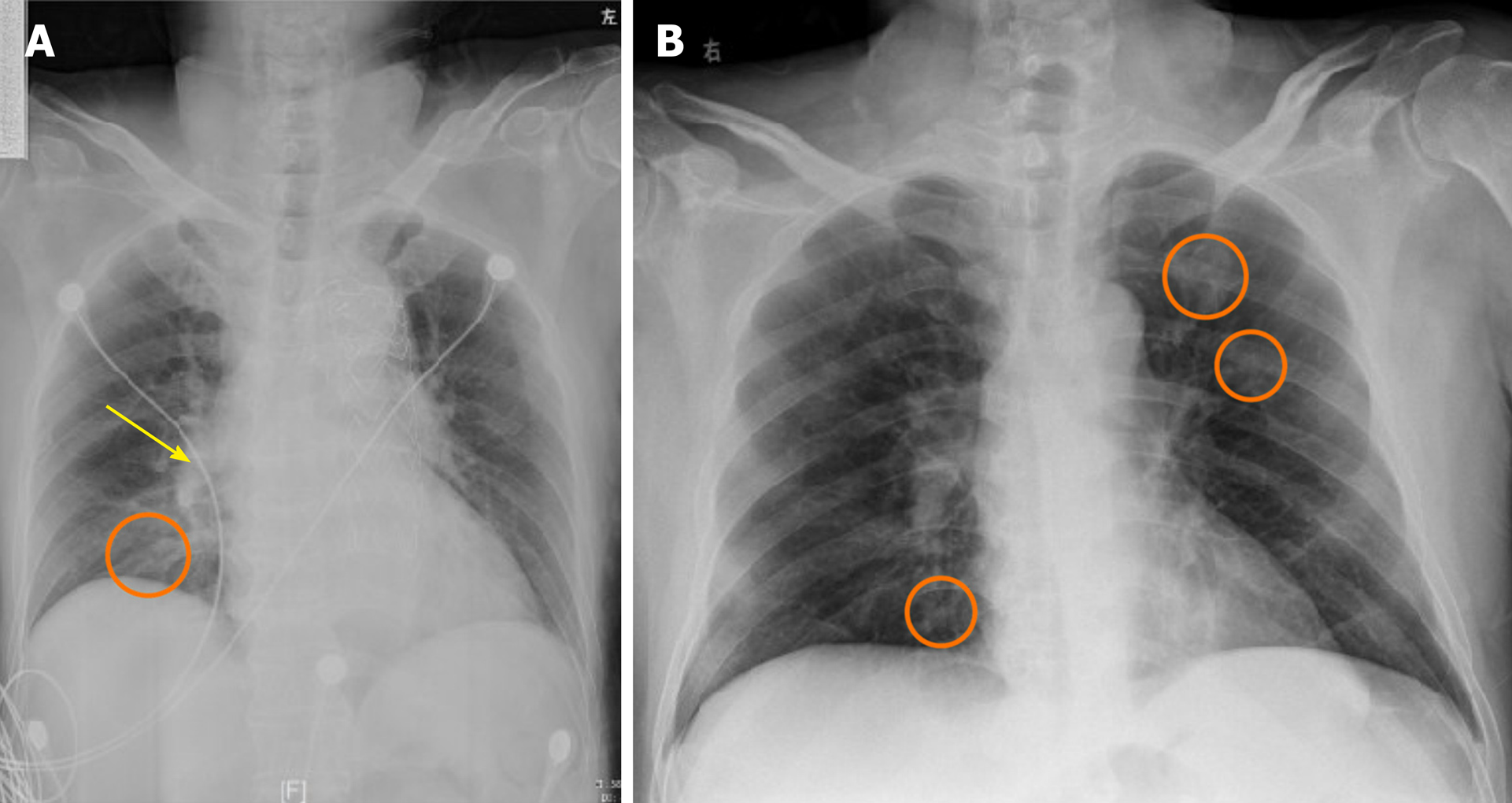

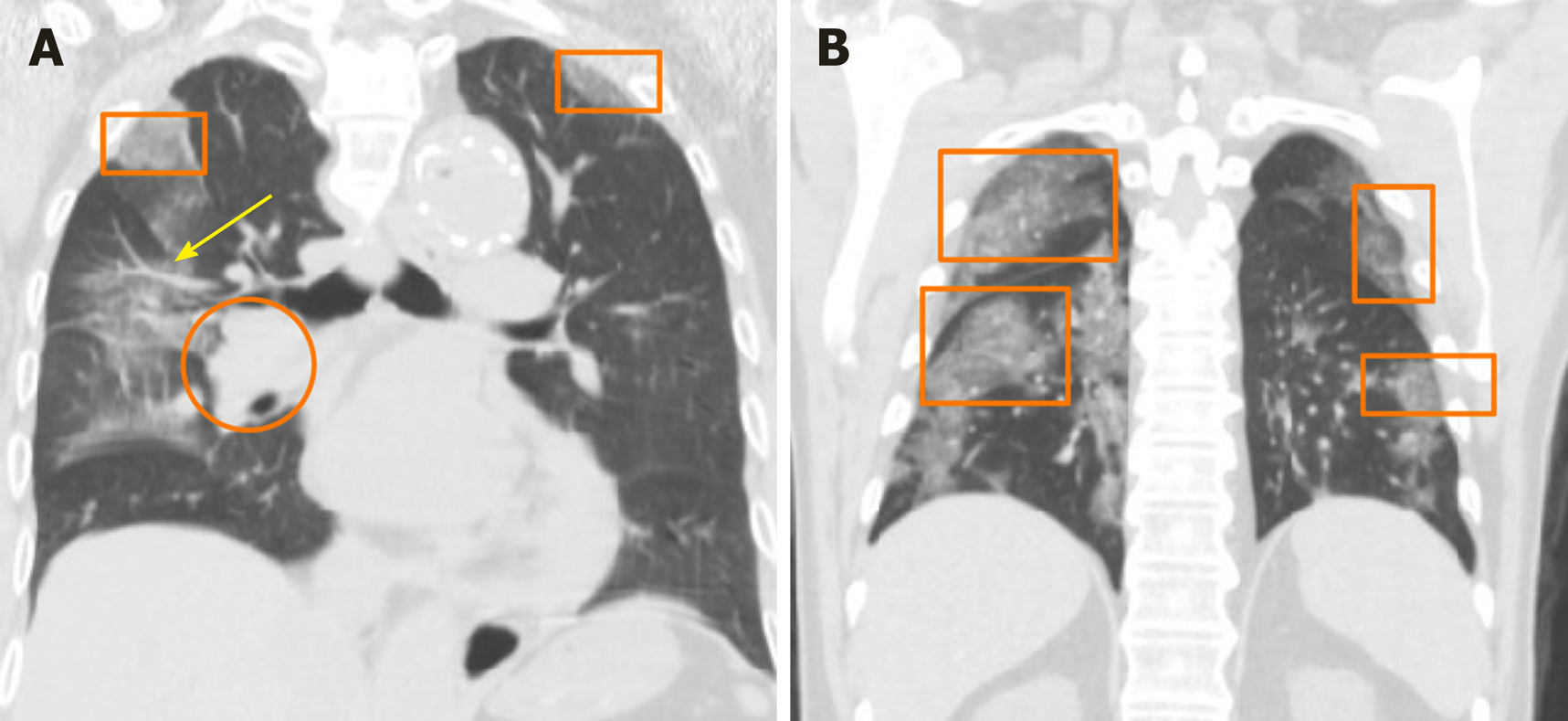

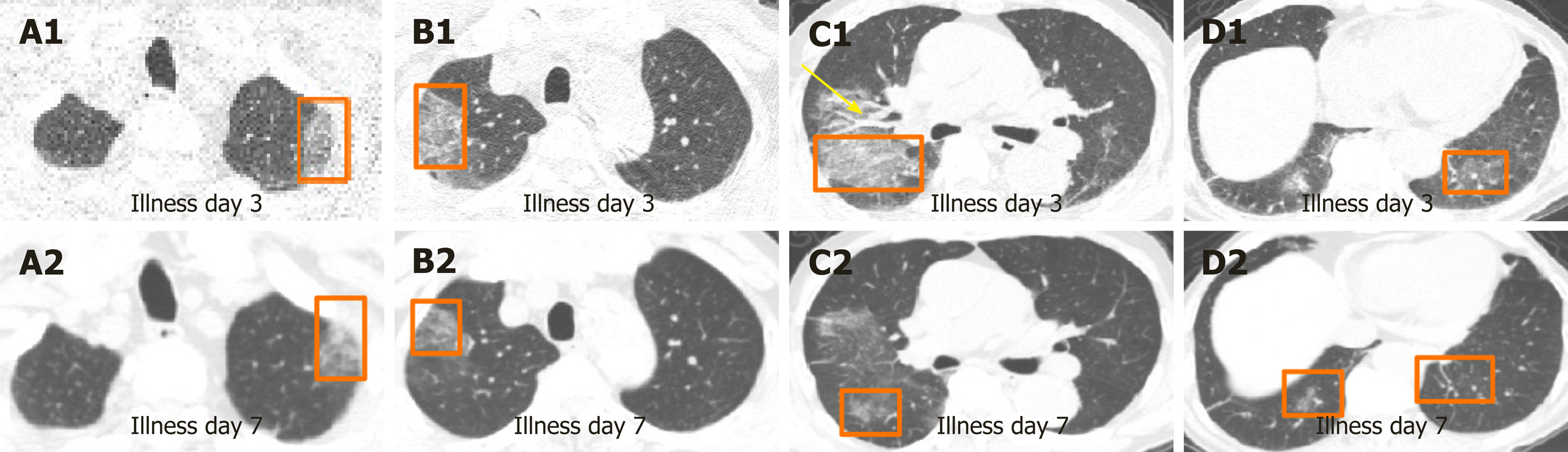

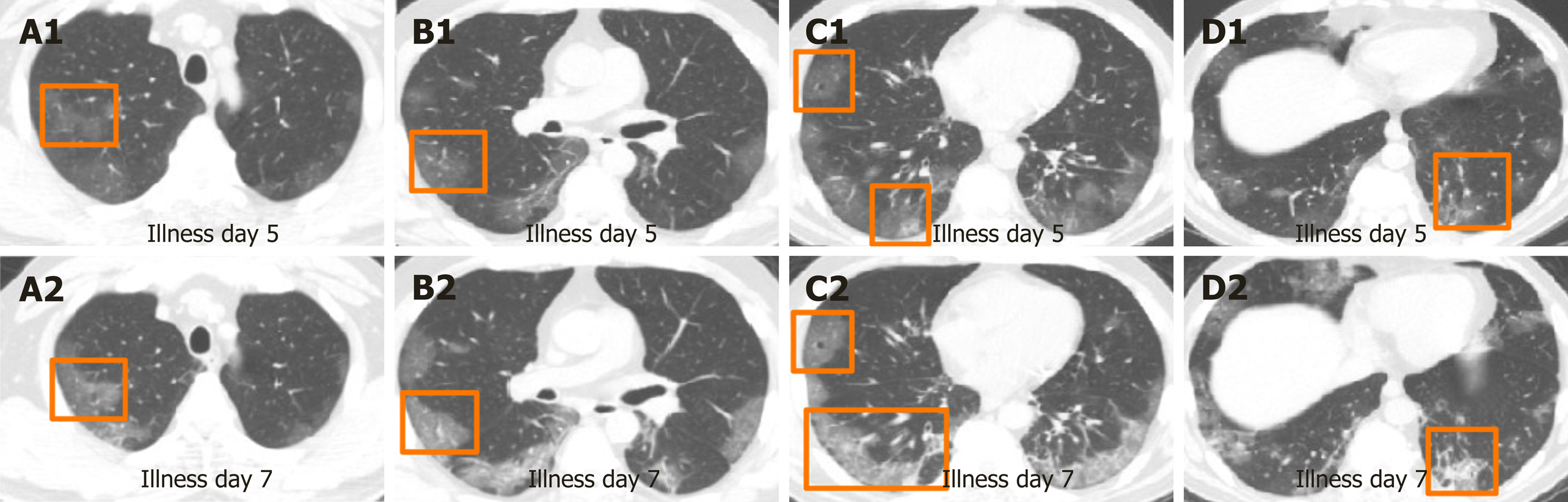

Initial imaging evaluation with chest X-ray on the day of fever onset showed increased lung markings with bilateral opacification mainly in the inner and middle belts of the lung, and the hilar shadow was enlarged and thickened (Figure 2A and 3A). On the 3rd d after fever onset, the chest CT scan confirmed multiple flaky ground-glass shadows in the right lung, left upper lung, and the left lower lung (Figure 4A1, B1, C1, and D1). Thickened blood vessels and fibrous stripes were seen in some lesions of the right lung. The diagnosis of COVID-19 could not be excluded based on these CT scan findings.

The final diagnosis of the presented case was bacterial pneumonia with cardiogenic pulmonary edema.

Considering the CT findings, the lung lesion was primarily characterized as viral pneumonia. The patient was given 0.2 g three times daily oral Arbidol, an empiric oral antiviral therapy during in-hospital treatment. In addition, 2 g QD Ceftriaxone and 0.4 g QD Levofloxacin were prescribed due to increased PCT, CRP, and neutrophil counts. The patient received 20 mg twice daily oral furosemide and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease due to elevated NTproBNP and acute myocardial infarction.

After 7 d of treatment, the patient’s symptoms improved significantly. He recovered from the fever, and the chest tightness and cough were relieved. Further, re-examinations of CT on the 7th d revealed a reduction in multiple ground-glass opacities in the right lung, left upper lung, and the left lower lung (Figure 4A2, B2, C2 and D2). The PCT was normal, and the CRP significantly decreased on the 7th d of illness. He was discharged on day 12 without obvious discomfort after the fever.

COVID-19 is an acute infectious pneumonia caused by a new strain of coronavirus that has not previously been identified in humans until late December 2019[5]. Evidence shows that human-to-human transmission has occurred through contact and droplets[4,6,7]. The natural and intermediate host of the SARS-CoV-2 may be horseshoe bat[8] and pangolin[9], respectively. The SARS-CoV-2 belongs to a cluster of betacoronaviruses, and it shares 76.4% genome sequence homology to SARS-CoV[10]. The SARS-CoV-2 binds to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), a similar receptor to SARS-CoV[10], to infect the host. However, the affinity of ACE2 binding to SARS-CoV-2 is 10 to 20 fold than that of SARS-CoV[11]. The basic reproduction number of SARS-CoV-2 was higher than that of SARS-CoV[12,13], which meant stronger human transmission than SARS. Fever, fatigue, dry cough, expectoration, poor appetite, and myalgia were the common symptoms of COVID-19, whereas dizziness, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, rhinobyon, and conjunctival congestion were rare conditions of the disease[14,15]. Most COVID-19 patients have leukopenia and lymphopenia and elevated CRP but normal PCT[4]. About 86.4% of these patients have abnormal chest CT images. About 85.4% of COVID-19 cases are mild[16], but some progress rapidly and cause multiple organ failure. Additionally, the overall mortality rate of COVID-19 is 1.4%, where the mortality rate for ICU patients ranges from 5% to 61.5%[15,17].

The 65-year-old male, who had no epidemiologic history, but had fever, cough, lymphopenia, and CT images of multiple patchy GGOs, was a suspected case of COVID-19 according to the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pneumonia Caused by 2019-nCoV (version 5)[4]. The patient underwent a series of COVID-19 tests as reco-mmended. Throat swab tests for the SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid test were performed four times using the real time reverse transcriptase-PCR assay, and the results were negative. Based on the Chinese standards of Pneumonia Caused by 2019-nCoV, the patient could have been discharged from the hospital[4], but he was hospitalized for 1 wk at the cardiovascular internal medicine department before admission to the isolation ward. A misdiagnosis of COVID-19 can result in serious adverse consequences, such as cross infection among patients and healthcare workers. Additionally, several studies have found as high as 20% false-negative rates of the COVID-19 real time reverse transcriptase-PCR test[18-20]. Other detection methods were therefore recommended.

Another study suggested that on day 5 of the onset, the immunoglobulin (Ig) G and IgM of SARS-CoV-2 could be detected in the blood of almost all patients, while the detection rate of SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid in throat swabs was only in 25% of the patients[21]. We collected blood samples of our patient to detect the IgM and IgG of SARS-CoV-2 on day 8 of onset, and the results were negative. We thus excluded the diagnosis of the novel coronavirus pneumonia in terms of etiology. Besides, the patient was an elderly man with underlying cardiovascular diseases such as acute myocardial infarction, cardiac insufficiency, and hypertension. According to the early warning model for predicting mortality in viral pneumonia (MuLBSTA score, which contains six indexes, including multiple infiltrations, lymphocytopenia, bacterial coinfection, smoking history, hypertension, and age[22]), our patient was at a high risk of death. Some studies have confirmed that COVID-19 cases in older patients with underlying comorbidities, including cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease, have a higher rate of becoming critically ill or dying[5,14,17]. However, after antibacterial strategy, diuretic treatment, and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease, there was a significant improvement in fever, cough, and chest tightness on day 7. Therefore, the 65-year-old male patient was excluded from COVID-19 diagnosis based on the disease progression.

Chest CT scan is valuable and helpful in the diagnosis of COVID-19, and its diagnostic sensitivity was 97% in the epidemic area. A study involving 63 patients suggested that the imaging characteristics of COVID-19 included GGO (85.7%), ground-glass nodules (22.2%), patchy consolidation (19%), fibrous stripe (17.5%), and irregular solid nodules (12.7%)[23]. The predominant CT feature of COVID-19 was GGO, which was gradually followed by crazy-paving pattern and consolidation. In the first 2 wk, the lesions were increased and consolidated. After 2 wk, the lesions were absorbed, leaving a wide range of GGO and subpleural consolidation shadow[24]. The CT images of our 65-year-old suspected case of COVID-19 showed that there were multiple patchy GGOs, ground-glass nodules, crazy-paving pattern, and consolidation in bilateral lungs, which were typical features of COVID-19. However, the GGO of this patient, which was confirmed to be associated with cardiogenic pulmonary edema, was mainly in the parahilar regions and gravitational distribution. The lesions of COVID-19 are mainly distributed in the subpleural area (Figure 2B and 3B) because the SARS-CoV-2 mainly attacks type II alveolar epithelial cell[25].

In addition, the patient’s CT images were characterized by thickened pulmonary vascular shadows, the typical feature of cardiogenic pulmonary edema. In patients with cardiogenic pulmonary edema, the increase of pulmonary vascular pressure, caused by cardiac insufficiency, triggers the pulmonary capillary fluid exuding into the pulmonary interstitium. However, the pulmonary edema of the novel coronavirus pneumonia is due to the disruption of the alveolar-capillary barrier with protein-rich fluid entering the interstitial spaces and alveolar cavities[26,27]. The mechanism that protein-rich edema cannot transfer to the central area might explain why the noncardiogenic edema lacks bronchial vascular bundle thickening[28]. In the patient, the lung lesions were significantly absorbed, the density was reduced, and the thickened pulmonary vascular shadows disappeared on day 7 after the onset of symptoms using the diuretic treatment. The lack of further enlarged and consolidated lesions disqualified the radiographic features of novel coronavirus pneumonia. Although the CT imaging of our suspected case could be easily confused with that of the coronavirus pneumonia, it can be further disqualified based on the distribution area of the lung lesions, the presence of vascular thickening, and the evolution of the COVID-19-related CT images (Figure 5).

This case report can provide a certain reference for the differential diagnosis of COVID-19 in the early stage and reduce panic to a certain extent. But the defect is that more cases need to be verified.

Distinguishing COVID-19 patients from those with bacterial pneumonia with cardiogenic pulmonary edema can be difficult and therefore requires serious identification. Further, serological antibody detection of SARS-CoV-2 coupled with chest CT scans can improve the differential diagnosis of COVID-19.

We acknowledge the contribution of Yu KH to radiologic interpretation.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Bansal A, Carnevale S S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Lu H, Stratton CW, Tang YW. Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan, China: The mystery and the miracle. J Med Virol. 2020;92:401-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1670] [Cited by in RCA: 1768] [Article Influence: 353.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | World Health Organization. Novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV): Situation report-15. Available from: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200204-sitrep-15-ncov.pdf?sfvrsn=88fe8ad6_2. |

| 3. | National Health Commission. Notification of 2019-nCoV infection. Available from: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/yqtb/202002/26fb16805f024382bff1de80c918368f.shtml. |

| 4. | National Health Commission. Diagnosis and Treatment of Pneumonia Caused by 2019-nCoV (version 5). Available from: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653p/202002/3b09b894ac9b4204a79db5b8912d4440.shtml. |

| 5. | Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, Qiu Y, Wang J, Liu Y, Wei Y, Xia J, Yu T, Zhang X, Zhang L. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14869] [Cited by in RCA: 12968] [Article Influence: 2593.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Chan JF, Yuan S, Kok KH, To KK, Chu H, Yang J, Xing F, Liu J, Yip CC, Poon RW, Tsoi HW, Lo SK, Chan KH, Poon VK, Chan WM, Ip JD, Cai JP, Cheng VC, Chen H, Hui CK, Yuen KY. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395:514-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6483] [Cited by in RCA: 5420] [Article Influence: 1084.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Phan LT, Nguyen TV, Luong QC, Nguyen TV, Nguyen HT, Le HQ, Nguyen TT, Cao TM, Pham QD. Importation and Human-to-Human Transmission of a Novel Coronavirus in Vietnam. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:872-874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 758] [Cited by in RCA: 695] [Article Influence: 139.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, Si HR, Zhu Y, Li B, Huang CL, Chen HD, Chen J, Luo Y, Guo H, Jiang RD, Liu MQ, Chen Y, Shen XR, Wang X, Zheng XS, Zhao K, Chen QJ, Deng F, Liu LL, Yan B, Zhan FX, Wang YY, Xiao GF, Shi ZL. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15248] [Cited by in RCA: 14108] [Article Influence: 2821.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Xiao K, Zhai J, Feng Y, Zhou N, Zhang X, Zou JJ, Li N, Guo Y, Li X, Shen X, Zhang Z, Shu F, Huang W, Li Y, Zhang Z, Chen RA, Wu YJ, Peng SM, Huang M, Xie WJ, Cai QH, Hou FH, Chen W, Xiao L, Shen Y. Isolation of SARS-CoV-2-related coronavirus from Malayan pangolins. Nature. 2020;583:286-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 414] [Cited by in RCA: 493] [Article Influence: 98.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Xu X, Chen P, Wang J, Feng J, Zhou H, Li X, Zhong W, Hao P. Evolution of the novel coronavirus from the ongoing Wuhan outbreak and modeling of its spike protein for risk of human transmission. Sci China Life Sci. 2020;63:457-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1252] [Cited by in RCA: 1314] [Article Influence: 262.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wrapp D, Wang N, Corbett KS, Goldsmith JA, Hsieh CL, Abiona O, Graham BS, McLellan JS. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science. 2020;367:1260-1263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5792] [Cited by in RCA: 6472] [Article Influence: 1294.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tang B, Wang X, Li Q, Bragazzi NL, Tang S, Xiao Y, Wu J. Estimation of the Transmission Risk of the 2019-nCoV and Its Implication for Public Health Interventions. J Clin Med. 2020;9:462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 929] [Cited by in RCA: 701] [Article Influence: 140.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lipsitch M, Cohen T, Cooper B, Robins JM, Ma S, James L, Gopalakrishna G, Chew SK, Tan CC, Samore MH, Fisman D, Murray M. Transmission dynamics and control of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Science. 2003;300:1966-1970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1108] [Cited by in RCA: 886] [Article Influence: 40.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, Wang B, Xiang H, Cheng Z, Xiong Y, Zhao Y, Li Y, Wang X, Peng Z. Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061-1069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14113] [Cited by in RCA: 14761] [Article Influence: 2952.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, Liu L, Shan H, Lei CL, Hui DSC, Du B, Li LJ, Zeng G, Yuen KY, Chen RC, Tang CL, Wang T, Chen PY, Xiang J, Li SY, Wang JL, Liang ZJ, Peng YX, Wei L, Liu Y, Hu YH, Peng P, Wang JM, Liu JY, Chen Z, Li G, Zheng ZJ, Qiu SQ, Luo J, Ye CJ, Zhu SY, Zhong NS; China Medical Treatment Expert Group for Covid-19. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708-1720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19202] [Cited by in RCA: 18861] [Article Influence: 3772.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 16. | Epidemiology Working Group for NCIP Epidemic Response, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. [The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China]. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41:145-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1341] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, Shu H, Xia J, Liu H, Wu Y, Zhang L, Yu Z, Fang M, Yu T, Wang Y, Pan S, Zou X, Yuan S, Shang Y. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:475-481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6231] [Cited by in RCA: 6656] [Article Influence: 1331.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Xie X, Zhong Z, Zhao W, Zheng C, Wang F, Liu J. Chest CT for Typical Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pneumonia: Relationship to Negative RT-PCR Testing. Radiology. 2020;296:E41-E45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1213] [Cited by in RCA: 1211] [Article Influence: 242.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Li D, Wang D, Dong J, Wang N, Huang H, Xu H, Xia C. False-Negative Results of Real-Time Reverse-Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction for Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2: Role of Deep-Learning-Based CT Diagnosis and Insights from Two Cases. Korean J Radiol. 2020;21:505-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 250] [Article Influence: 50.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ai T, Yang Z, Hou H, Zhan C, Chen C, Lv W, Tao Q, Sun Z, Xia L. Correlation of Chest CT and RT-PCR Testing for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: A Report of 1014 Cases. Radiology. 2020;296:E32-E40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3614] [Cited by in RCA: 3283] [Article Influence: 656.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zhang W, Du RH, Li B, Zheng XS, Yang XL, Hu B, Wang YY, Xiao GF, Yan B, Shi ZL, Zhou P. Molecular and serological investigation of 2019-nCoV infected patients: implication of multiple shedding routes. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:386-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1192] [Cited by in RCA: 1219] [Article Influence: 243.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Guo L, Wei D, Zhang X, Wu Y, Li Q, Zhou M, Qu J. Clinical Features Predicting Mortality Risk in Patients With Viral Pneumonia: The MuLBSTA Score. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:2752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 241] [Cited by in RCA: 284] [Article Influence: 47.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Pan Y, Guan H, Zhou S, Wang Y, Li Q, Zhu T, Hu Q, Xia L. Initial CT findings and temporal changes in patients with the novel coronavirus pneumonia (2019-nCoV): a study of 63 patients in Wuhan, China. Eur Radiol. 2020;30:3306-3309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 564] [Cited by in RCA: 632] [Article Influence: 126.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Pan F, Ye T, Sun P, Gui S, Liang B, Li L, Zheng D, Wang J, Hesketh RL, Yang L, Zheng C. Time Course of Lung Changes at Chest CT during Recovery from Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Radiology. 2020;295:715-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1617] [Cited by in RCA: 1759] [Article Influence: 351.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, Schiergens TS, Herrler G, Wu NH, Nitsche A, Müller MA, Drosten C, Pöhlmann S. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell 2020; 181: 271-280. e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11946] [Cited by in RCA: 14250] [Article Influence: 2850.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Tian S, Hu W, Niu L, Liu H, Xu H, Xiao SY. Pulmonary Pathology of Early-Phase 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pneumonia in Two Patients With Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15:700-704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 927] [Cited by in RCA: 1000] [Article Influence: 200.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Murray JF. Pulmonary edema: pathophysiology and diagnosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:155-160. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Milne EN, Pistolesi M, Miniati M, Giuntini C. The radiologic distinction of cardiogenic and noncardiogenic edema. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1985;144:879-894. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |