Published online Nov 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i22.5795

Peer-review started: August 21, 2020

First decision: September 13, 2020

Revised: September 13, 2020

Accepted: September 23, 2020

Article in press: September 23, 2020

Published online: November 26, 2020

Processing time: 96 Days and 7.6 Hours

Hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome is caused by hantaviruses presenting with high fever, hemorrhage, and acute kidney injury. Microvascular injury and hemorrhage in mucus were often observed in patients with hantavirus infection. Infection with bacterial and virus related aortic aneurysm or dissection occurs sporadically. Here, we report a previously unreported case of hemorrhagic fever with concurrent aortic dissection.

A 56-year-old man complained of high fever and generalized body ache, with decreased platelet counts of 10 × 109/L and acute kidney injury. The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays test for immunoglobulin M and immunoglobulin G hantavirus-specific antibodies were both positive. During the convalescent period, he complained sudden onset acute chest pain radiating to the back, and the computed tomography angiography revealed an aortic dissection of the descending aorta extending to iliac artery. He was diagnosed with hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome and Stanford B aortic dissection. The patient recovered completely after surgery with other support treatments.

Hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome complicated with aortic dissection is rare and a difficult clinical condition. Hantavirus infection not only causes microvascular damage presenting with hemorrhage but may be risk factor for acute macrovascular detriment. A causal relationship has yet to be confirmed.

Core Tip: Microvascular injury presenting with hemorrhage in mucus is a typical symptom in hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) patients. Infection related aortic dissection occurs sporadically, and there has been no report of concurrent HFRS and aortic dissection. HFRS complicated with aortic dissection is rare and a difficult clinical condition that deserves further study and discussion.

- Citation: Qiu FQ, Li CC, Zhou JY. Hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome complicated with aortic dissection: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(22): 5795-5801

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i22/5795.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i22.5795

Hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) is caused by hantaviruses (such as Hantan, Seoul, and Puumala viruses), which are carried by a specific rodent host species and transmitted through their saliva, urine, feces, and blood[1]. In China, Hantaan virus and Seoul virus infections are two main pathogens for HFRS, with more than 11000 cases reported annually[2]. The most common classic HFRS presents with high fever, loin or abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, malaise, and conjunctival hemorrhage, which progresses to acute kidney injury. Hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome is another life-threatening clinical syndrome infected by Sin Nombre virus in the United States and Andes virus in South America[3]. Since hantavirus primarily infects endothelial cells, it had been shown that hantavirus infection induces the leakage of vascular endothelial cells and presents with pleural or perirenal effusion in patients[4]. The clinical course, from fever to abrupt hypotension with oliguria, can be extremely variable, and some patients are asymptomatic.

Aortic dissection is a lethal and critical disease, presenting with the separation of the aortic wall layers and subsequent formation of a false lumen[5]. The Stanford B aortic dissection is defined as the appearance of a false lumen at the segment distal to the left subclavian artery. Risk factors of aortic dissection include hypertension, genetic disorders, and inflammation of the aortic wall, etc.[6]. Infection related aortic dissection is a rare life threatening condition because of the possibility of rupture as well as perforation to surrounding organs. Although less common, infective aortic disease due to bacteria (such as staphylococcus, salmonella, mycobacteria) and virus (such as Zoster Virus) have been reported[7,8]. The infection caused inflammatory response in the vascular media may lead to aortic dilation and formation of aneurysm[9]. In this report, we present a case of HFRS with concurrent aortic dissection during the convalescent period.

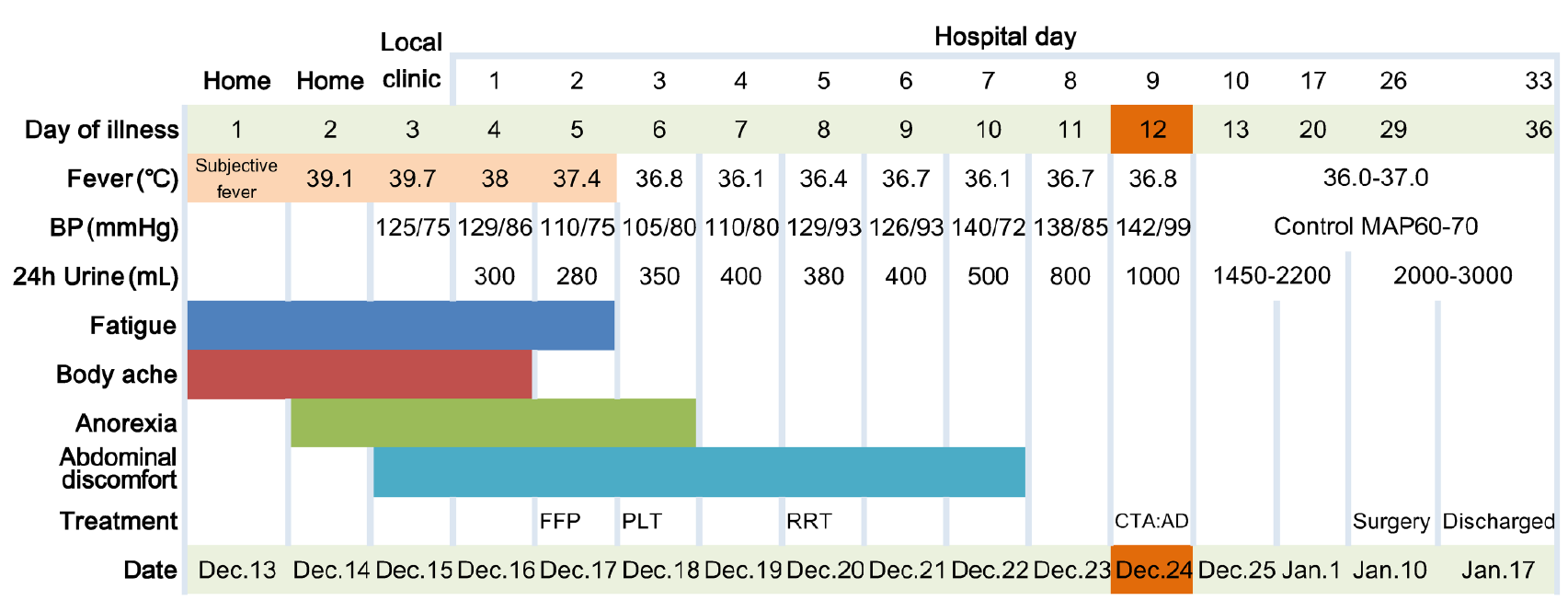

A 56-year-old man presented to our emergency department complaining of high fever (the highest recorded oral temperature 39.7 °C), fatigue, and generalized body ache for 3 d (Figure 1).

The patient lived in a rural area and worked in a place overrun with rats. The symptoms started 3 d ago with no obvious cause of fever. A peak oral temperature of 39.7 °C was recorded, with fatigue and generalized body ache. He went to a local clinic and anti-infection treatments were given. There was no remission, and blood tests showed an increased white blood cells (WBC) with dramatically decreased platelets, following which the man was admitted to our hospital.

The patient did not have any history of past illnesses.

There was no family history of any congenital anomalies.

On admission, his oral temperature was 38.0 °C, respiratory rate 19 breaths/min, heart rate 78 beats/min, and blood pressure 129/86 mmHg. Physical examination found a poor general condition, and petechiae in the mouth and on the neck.

The local clinic blood test showed an increased WBC (11.1 × 109/L) with dramatically decreased platelets (36 × 109/L). On the 1st d in our hospital, blood tests revealed the following: WBC 14.9 × 109/L, hemoglobin 212 g/L, platelets 10 × 109/L, alanine aminotransferase 66 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase 108 U/L, lactic dehydrogenase 1079 IU/L, creatinine 187 μmol/L, and C-reactive protein 33.3 mg/L (reference: 0-5). The coagulation function test showed prothrombin time 15.5 s (reference: 11.5-14.5) and partial thromboplastin time 91.2 s. The laboratory results and reference range are listed in Table 1. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays of Ig (immunoglobulin)M and IgG hantavirus-specific antibodies for hantavirus were both positive.

| Measure | Hospital day | |||||||||

| Reference range | Local clinic | 1 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 12 | 14 | 24 | 33 | |

| WBC as × 109/L | 2.5-9.5 | 11.1 | 14.9 | 26.4 | 10 | 7.6 | 10 | 6.8 | 9 | 8.5 |

| PLT as × 109/L | 125-350 | 36 | 10 | 18 | 41 | 84 | 125 | 186 | 417 | 384 |

| Hb in g/L | 130-175 | 197 | 212 | 177 | 134 | 135 | 114 | 91 | 98 | 89 |

| Creatinine in μmol/L | 57-97 | _ | 187 | 598 | 907 | 782 | 445 | 170 | 122 | 88 |

| ALT in U/L | 9-50 | _ | 66 | 51 | 50 | _ | 36 | 55 | 91 | 40 |

| AST in U/L | 15-40 | _ | 108 | 102 | 88 | 55 | 69 | 61 | 86 | 22 |

| LDH in U/L | 120-250 | _ | 1079 | 1043 | 831 | 639 | 486 | 280 | 333 | 199 |

| APTT in s | 29.2-41.2 | _ | 81 | 54 | 46.4 | 42.6 | _ | _ | 44.9 | _ |

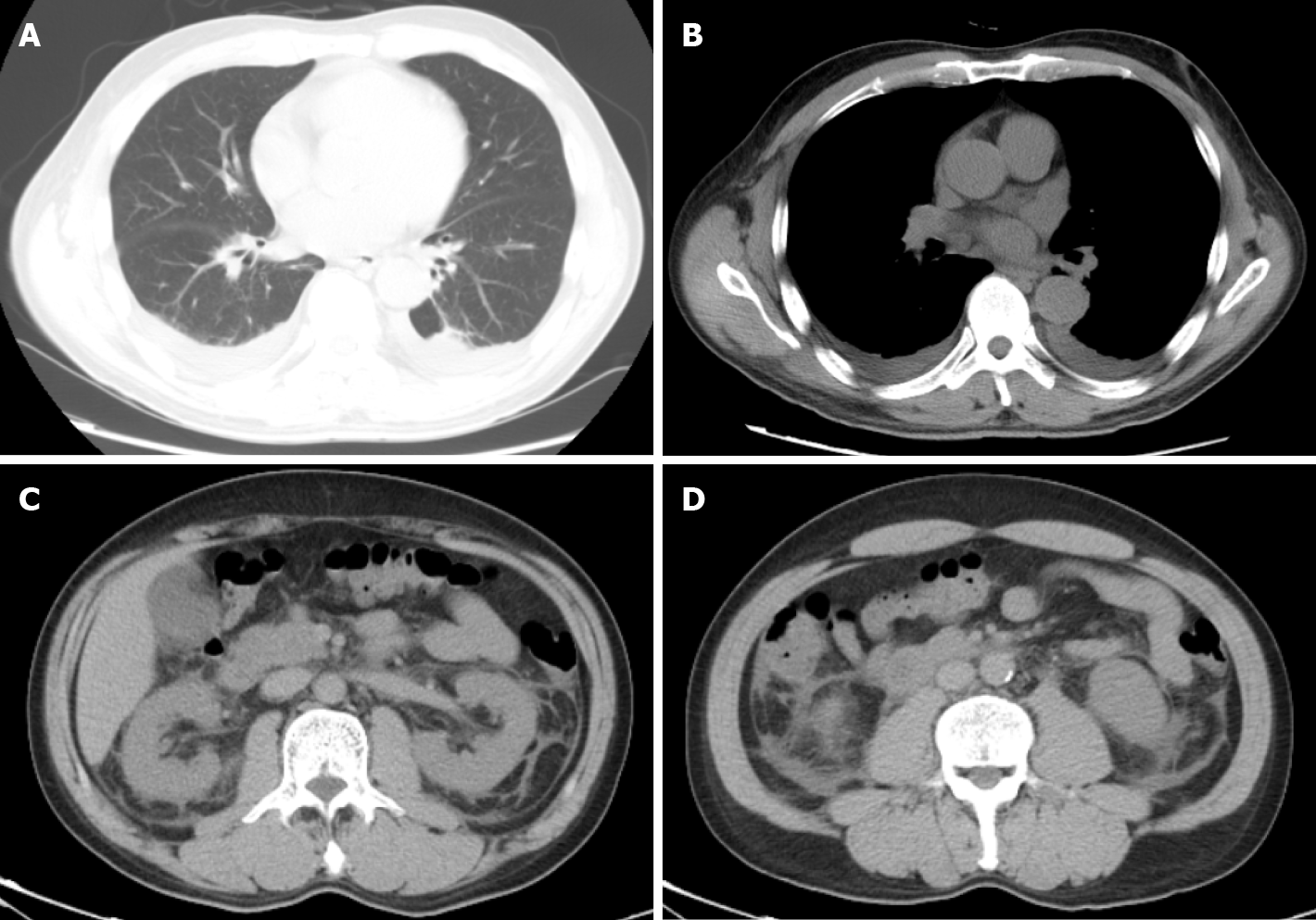

The computed tomography scan of chest and abdomen showed pleural effusion, perinephric effusion extended to paracolic sulcus, and slight peritoneal and pelvic effusion (Figure 2).

The final diagnosis of the case was hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome and Stanford B aortic dissection.

Initially, antibacterial drug piperacillin/tazobactam (4.5 g, every 8 h for 5 d) was empirically used to deal with abdomen effusion. On days 2 through 3 of hospitalization, the patient was treated with transfusion of platelets (20 u) and fresh frozen plasma (400 mL) to correct the hemostatic abnormalities. After full fluid resuscitation, the patient remained in an oliguric state and then received renal-replacement therapy on hospital day 5. On hospital day 26, when the platelets had recovered to normal level, he received an aortic angiography and thoracic endovascular aortic repair surgery. A week after the operation, the patient was discharged and followed up as outpatient (Figure 3).

His fever and body ache resolved on post-admission day 3. On hospital day 26, the platelets and urine output recovered to normal level. A week after the operation, the patient was discharged and followed up as an outpatient.

Hantaviruses are negative sense single stranded ribonucleic acids viruses, which can survive for more than 10 d as a virion at room temperature[10]. The exposure to aerosolized rodent excreta containing pathogenic virus is the main cause of human infection with hantaviruses[11]. Generally, HFRS is mainly caused by Hantaan virus and Dobrava virus in severe cases with mortality rates from 5% to 15%, whereas Seoul virus and Puumala virus are associated with moderate disease with mortality rates < 1%[12,13]. In China, HFRS is mainly caused by Hantaan virus and Seoul virus.

The diagnosis of hantavirus infections in humans can be confirmed according to the epidemiological and clinical information as well as laboratory tests. The classical manifestation of HFRS includes high fever, conjunctival hemorrhage, and gastrointestinal symptoms like abdominal pain, malaise, nausea, and vomiting. Some patients develop severe oliguric acute kidney injury and need hemodialysis. Patients typically have abnormal laboratory values including a leukocytosis, throm-bocytopenia, and elevation of serum creatinine and lactate dehydrogenase.

The serological test to detect IgM/IgG antibodies of the three structural hantavirus proteins using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays is a practical clinical laboratory method to confirm the hantavirus infection[12]. The serotype of the hantavirus can be verified by real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. However, because of condition limitations, we were not able to perform real time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction to confirm the serotype of the virus. This is one of the limitations of the case report. Notwithstanding this concern, this did not prevent clinical diagnosis of the HFRS and timely treatment in the present case.

Increased vascular permeability appears to be a dramatic expression of this patient, which had pleural and perinephric effusion according to the computed tomography scan. In patients, hantavirus replicates primarily in the endothelium, which cause damage to vascular endothelium (tubular and interstitial), increasing further the permeability[1]. The increased vascular permeability is mediated in part by bradykinin and cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-6[3]. All of these pathogenesis can increase the possibility of vascular inflammation, damage, and hemorrhage in HFRS.

Infection with virus or bacterial related aortic aneurysm or dissection has been reported sporadically. Staphylococcus aureus and Salmonella species were reported to cause aortic dissection[5]. Virus infection such as herpes zoster, human immu-nodeficiency virus, and varicella-zoster virus can also lead to vascular dissection[13]. However, the exact mechanisms of infection related vascular dissection are still far from clear. Prior reports suggested that viruses might lead to inflammatory injury of the arterial wall, leading subsequently to the development of the artery dissection[14]. During the recovery period of HFRS, our patient developed a sudden aortic dissection on day 10 in hospital. A multivariate analysis confirmed that the dissection was independently associated with a diagnosis of recent infection[9]. In addition, the hantavirus caused coagulation disorders and thrombocytopenia, which could contribute to the risk of aortic dissection. As there were no previous hantavirus infection cases with aortic complications reported, a future study should attempt to investigate whether this concurrent is causal. Although the hantavirus may not be the direct cause of aortic dissection, we suppose that this infection could lead to a damaged vessel wall and may contribute to subsequent dissection. Further investigations with larger patient groups of hantavirus infection and associated data of dissected vessels are needed to support this hypothesis.

We present an unreported case of HFRS complicated with aortic dissection, and no previous study has reported the association of HFRS with aortic disease. However, it is reasonable to suppose that hantavirus infection may not only lead to microvascular damage but also may be risk factor for macrovascular detriment in HFRS patients. The causal relationship has yet to be confirmed, and accumulation of cases of aortic disease with hantavirus infection is necessary in the future.

The authors appreciate the patient for agreeing to use his data for research purposes and for publication of this paper.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Umbro I S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Vaheri A, Strandin T, Hepojoki J, Sironen T, Henttonen H, Mäkelä S, Mustonen J. Uncovering the mysteries of hantavirus infections. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11:539-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 319] [Cited by in RCA: 367] [Article Influence: 30.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zhang S, Wang S, Yin W, Liang M, Li J, Zhang Q, Feng Z, Li D. Epidemic characteristics of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in China, 2006-2012. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Nichol ST, Spiropoulou CF, Morzunov S, Rollin PE, Ksiazek TG, Feldmann H, Sanchez A, Childs J, Zaki S, Peters CJ. Genetic identification of a hantavirus associated with an outbreak of acute respiratory illness. Science. 1993;262:914-917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 709] [Cited by in RCA: 675] [Article Influence: 21.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mackow ER, Gavrilovskaya IN. Hantavirus regulation of endothelial cell functions. Thromb Haemost. 2009;102:1030-1041. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Erbel R, Aboyans V, Boileau C, Bossone E, Bartolomeo RD, Eggebrecht H, Evangelista A, Falk V, Frank H, Gaemperli O, Grabenwöger M, Haverich A, Iung B, Manolis AJ, Meijboom F, Nienaber CA, Roffi M, Rousseau H, Sechtem U, Sirnes PA, Allmen RS, Vrints CJ; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. 2014 ESC Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases: Document covering acute and chronic aortic diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta of the adult. The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Aortic Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2873-2926. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2374] [Cited by in RCA: 3088] [Article Influence: 280.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nienaber CA, Clough RE. Management of acute aortic dissection. Lancet. 2015;385:800-811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 361] [Cited by in RCA: 439] [Article Influence: 43.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kozaki S, Miyamoto S, Uchida K, Shuto T, Tanaka H, Wada T, Anai H. Infected thoracic aortic aneurysm caused by Clostridium ramosum: A case report. J Cardiol Cases. 2019;20:103-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bhayani N, Ranade P, Clark NM, McGuinn M. Varicella-zoster virus and cerebral aneurysm: case report and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:e1-e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Grau AJ, Brandt T, Buggle F, Orberk E, Mytilineos J, Werle E, Conradt, Krause M, Winter R, Hacke W. Association of cervical artery dissection with recent infection. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:851-856. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Schmaljohn CS, Hasty SE, Dalrymple JM, LeDuc JW, Lee HW, von Bonsdorff CH, Brummer-Korvenkontio M, Vaheri A, Tsai TF, Regnery HL. Antigenic and genetic properties of viruses linked to hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome. Science. 1985;227:1041-1044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 282] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Clement J, LeDuc JW, Lloyd G, Reynes JM, McElhinney L, Van Ranst M, Lee HW. Wild Rats, Laboratory Rats, Pet Rats: Global Seoul Hantavirus Disease Revisited. Viruses. 2019;11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Avšič-Županc T, Saksida A, Korva M. Hantavirus infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019; 21S:e6-e16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Silvestri V, D'Ettorre G, Borrazzo C, Mele R. Many Different Patterns under a Common Flag: Aortic Pathology in HIV-A Review of Case Reports in Literature. Ann Vasc Surg. 2019;59:268-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hong A, Lee CS. Kaposi's sarcoma: clinico-pathological analysis of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and non-HIV associated cases. Pathol Oncol Res. 2002;8:31-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |