Published online Nov 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i22.5707

Peer-review started: July 24, 2020

First decision: September 12, 2020

Revised: September 22, 2020

Accepted: October 20, 2020

Article in press: October 20, 2020

Published online: November 26, 2020

Processing time: 124 Days and 3.2 Hours

Paraganglioma is a rare disease that can be lethal if undiagnosed. Thus, quick recognition is very important. Cardiac paragangliomas are found in patients who have hypertension. The classic symptoms are the triad of headaches, palpitations, and profuse sweating. We describe a very rare case of multiple paragangliomas of the heart and bilateral carotid artery without hypertension and outline the management strategies for this disease.

A 46-year-old man presented with the chief complaint of recently recurrent chest pain with a history of hemangioma of the bilateral carotid artery that had been surgically removed. He was found to have an intracardiac mass in the right atrioventricular groove and underwent successful excision. The final pathology demonstrated that the intracardiac mass was a cardiac paraganglioma, and the patient had an increased level of normetanephrine in the blood. The pathology and immunohistochemistry results showed that the bilateral carotid masses were also paragangliomas. During the 3 mo follow-up period, the patient did not experience recurrence of chest pain.

To our knowledge, this is the first case of multiple paragangliomas of the heart and neck without hypertension. This rare disease can be lethal if left undiagnosed. Thus, quick recognition is very important. The key to the diagnosis of cardiac paraganglioma is the presence of typical symptoms, including headaches, palpitations, profuse sweating, hypertension, and chest pain. Radiology can demonstrate the intracardiac mass. It is important to determine the levels of normetanephrine in the blood. The detection of genetic mutations is also recommended. Surgical resection is necessary to treat the disease and obtain pathological evidence.

Core Tip: Paraganglioma is a very rare disease. The clinical presentation of paraganglioma is dependent on the symptoms caused by local invasion and/or hypersecretion of catecholamines. The classic symptoms are the triad of headaches, palpitations, and profuse sweating. Surgical resection is necessary to treat the disease and obtain pathological evidence. We describe a first case of multiple paragangliomas of the heart and neck without hypertension and management with surgical resection.

- Citation: Wang Q, Huang ZY, Ge JB, Shu XH. Nonhypertensive male with multiple paragangliomas of the heart and neck: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(22): 5707-5714

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i22/5707.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i22.5707

The incidence of paraganglioma is approximately 6 cases per 1000000 person-years. This rare disease can be lethal if undiagnosed. Therefore, quick recognition is very important[1,2]. The clinical presentation of paraganglioma is dependent on the symptoms caused by local invasion and/or hypersecretion of catecholamines. Cardiac paragangliomas are found in 0.05%-0.2% of patients who have hypertension[3]. The classic symptoms are the triad of headaches, palpitations, and profuse sweating. Anxiety and panic attacks are also common. Cardiac paragangliomas can also be asymptomatic. To our knowledge, this is the first case of multiple paragangliomas of the heart and neck without hypertension. Here, we describe the case of a 46-year-old male with a history of hemangioma of the bilateral carotid artery who presented with recent recurrent chest pain and was found to have multiple paragangliomas of the heart and neck without hypertension, Table 1.

| Timeline of the patient | |

| Initial presentation | Presented with the chief complaint of recently recurrent chest pain |

| Day 1 | Echocardiography revealed an intracardiac mass in the right atrioventricular groove, wrapped around the proximal segment of the right coronary artery |

| Day 2 | Coronary artery computed tomography showed that abnormal blood vessels were presented between the right atrium and right ventricle |

| Day 5 | Coronary angiography showed that there were abundant blood vessels that were wrapped around and supplied the intracardiac mass in the right atrioventricular groove |

| Day 6 | Positron emission tomography/computed tomography suggested that the intracardiac mass was a malignant tumor |

| Day 8 | The level of normetanephrine in the blood was obviously increased |

| Day 18 | Open heart surgery was performed, and the intracardiac mass was completely excised. Quick freezing pathology indicated that the intracardiac mass was a mesenchymal malignant tumor |

| Day 25 | The final pathology results demonstrated that the intracardiac mass was a cardiac paraganglioma |

| Day 26 | The combination of pathological and immunohistochemistry results demonstrated bilateral carotid masses, these bilateral carotid masses were also paragangliomas |

| Day 27 | Discharged from hospital |

| Day 83 | At the 3-mo follow-up, the patient did not have recurrent chest pain |

A 46-year-old man presented to our hospital with the chief complaint of recently recurrent chest pain.

The patient had no history of present illness.

He had a history of hemangioma of the bilateral carotid artery that had been surgically removed in 2003 and 2018.

The patient had no personal or family history.

The patient’s heart rate was 125 beats/min, and blood pressure was 134/76 mmHg. There were no other abnormal findings on physical examination.

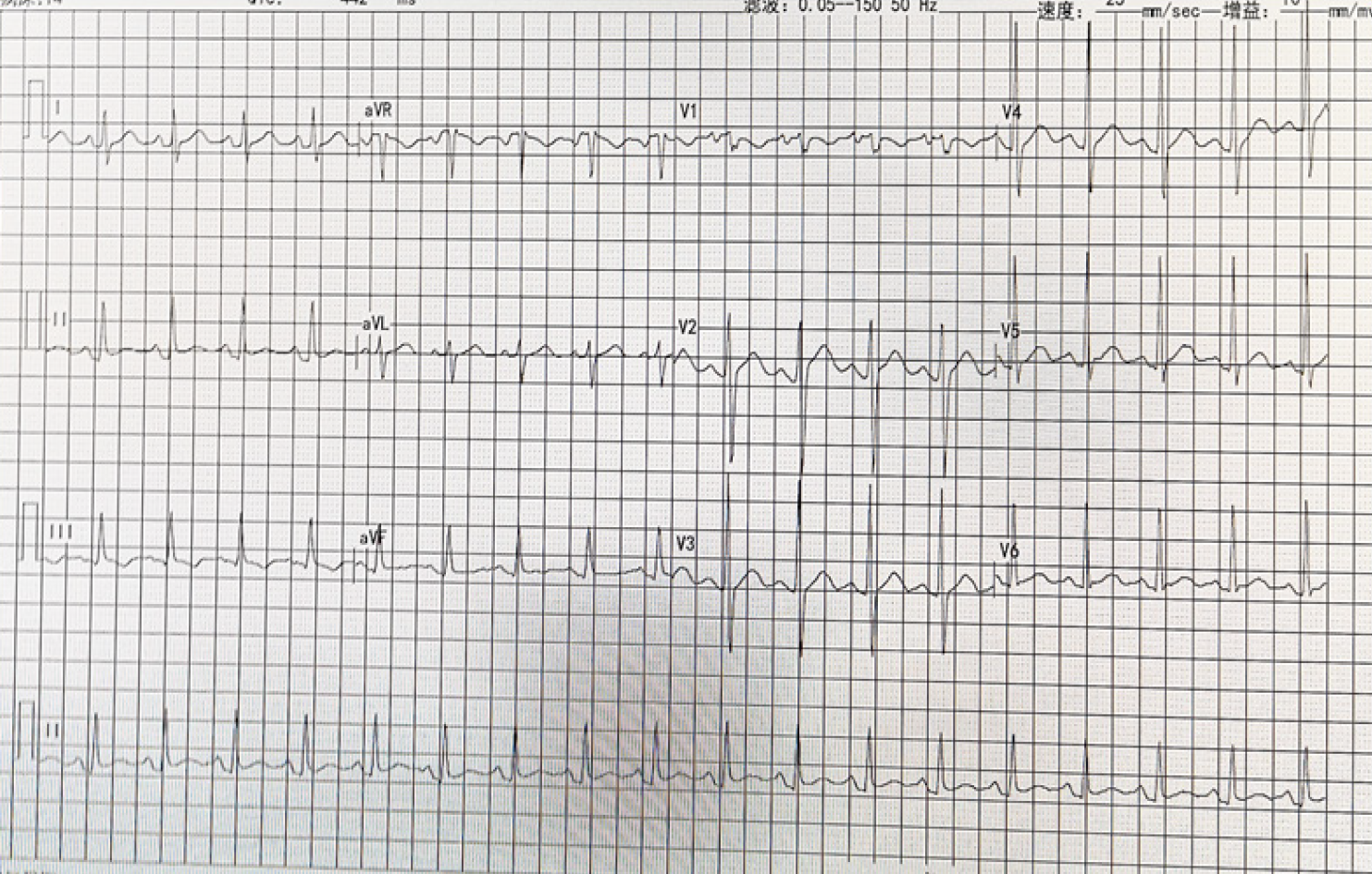

Electrocardiogram demonstrated sinus tachycardia (heart rate 125 beats/min) (Figure 1). Other laboratory examinations are shown in Table 2.

| Laboratory examinations | ||

| Variable | Reference range | Results (this hospital on arrival) |

| White cell count, × 109/L | 3.5-9.5 | 13.54 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 130-175 | 114 |

| Platelet count, × 109/L | 125-350 | 196 |

| Hematocrit, % | 40-50 | 34.7 |

| Urea nitrogen, mmol/L | 2.9-8.2 | 6.5 |

| Creatinine, μmol/L | 44-115 | 100 |

| Glucose, mmol/L | 3.9-5.6 | 5.6 |

| Sodium, mmol/L | 137-147 | 141 |

| Potassium, mmol/L | 3.5-5.3 | 3.9 |

| Chloride, mmol/L | 99-110 | 103 |

| Phosphorus, mmol/L | 0.9-1.34 | 0.93 |

| Calcium, mmol/L | 2.15-2.55 | 2.35 |

| Protein, g/L | ||

| Total | 65-85 | 68 |

| Albumin | 35-55 | 43 |

| Globulin | 20-40 | 25 |

| Cardiac troponin, ng/mL | < 0.03 | 0.011 |

| NT-proBNP, pg/mL | 0-100 | 52.9 |

| MM subtype of creatine kinase, U/L | 24-174 | 186 |

| Creatine kinase, U/L | 34-174 | 200 |

| FT3, pmol/L | 3.1-6.8 | 4.5 |

| FT4, pmol/L | 12-22 | 15.3 |

| TSH, μIU/mL | 0.27-4.2 | 3.65 |

| Prothrombin time | 10-13 | 10.8 |

| International normalized ratio | 0.5-1.2 | 0.99 |

| Partial thromboplastin time | 25-31.3 | 27.6 |

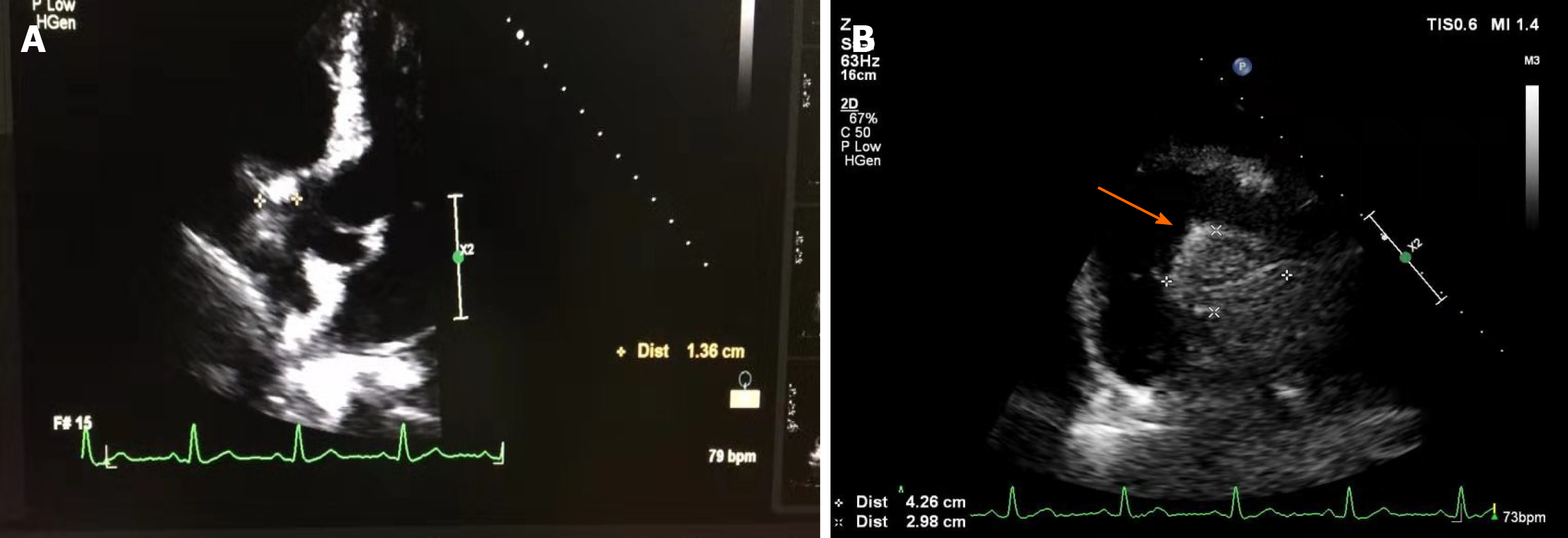

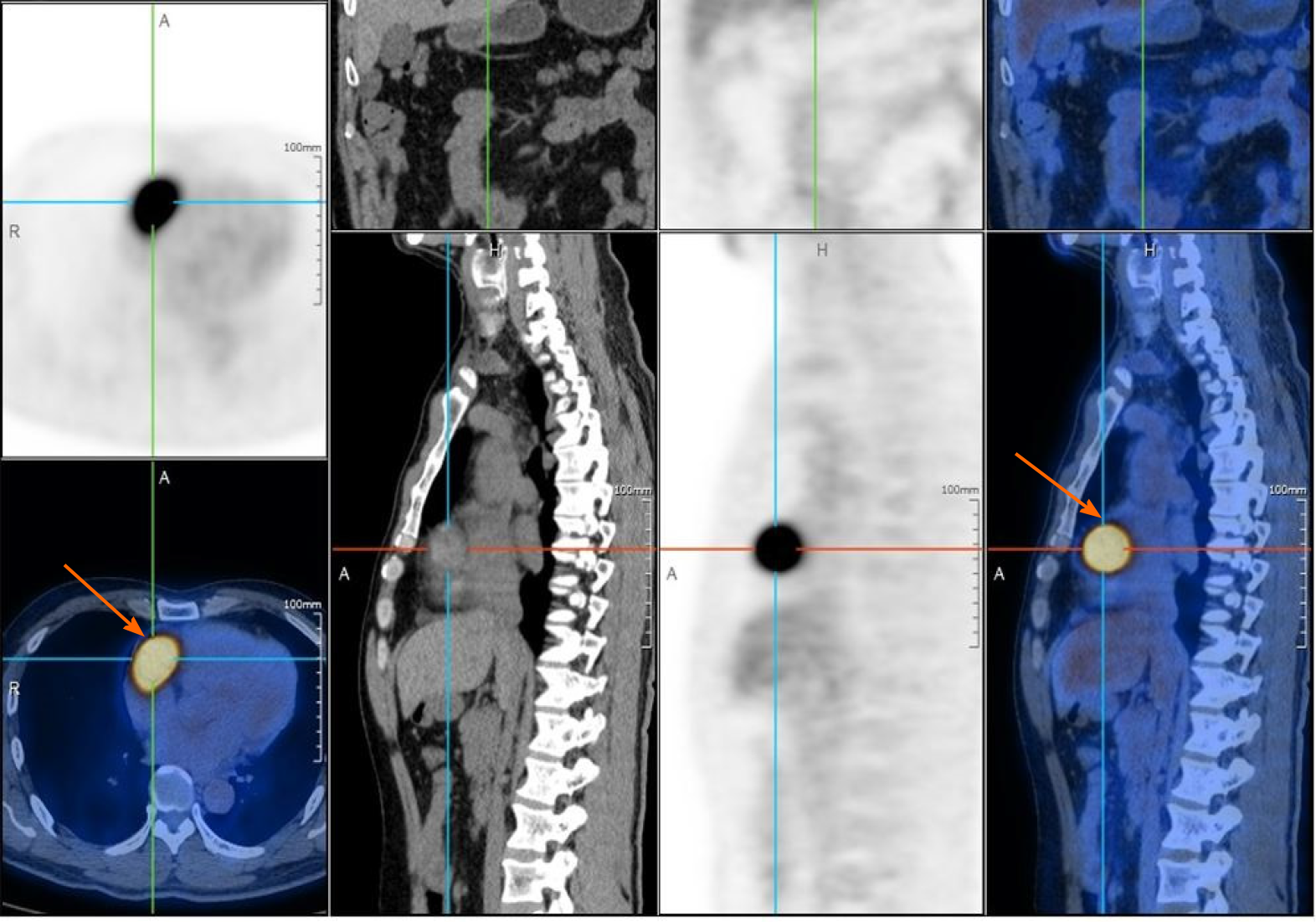

Echocardiography revealed a 4.26 cm × 2.98 cm intracardiac mass in the right atrioventricular groove, which was wrapped around the proximal segment of the right coronary artery (Figure 2). Coronary artery computed tomography (CT) showed that abnormal blood vessels were present between the right atrium and right ventricle, indicating that there might be a fistula between the right coronary artery and right atrium or a right coronary artery malformation. Coronary angiography (CAG) demonstrated that there were abundant blood vessels from the proximal segment of the right coronary artery that were wrapped around and supplied the intracardiac mass in the right atrioventricular groove (Figure 3). Positron emission tomography/CT suggested that the intracardiac mass in the right atrioventricular groove was a malignant tumor (Figure 4).

Normetanephrine blood level was 950.5 pg/mL, which was 5.8 times the upper limit of the normal range (normal range, < 163 pg/mL). The level of metanephrine and 3-methoxytryramine in the blood and vanillylmandelic acid in urine were all normal.

Considering his symptoms, physical examination, history, and laboratory examinations, we suspected that the intracardiac mass was a paraganglioma. The patient was referred to the Department of Cardiac Surgery. Open heart surgery was performed, and a dark red intracardiac mass was found located in the right atrioventricular groove. The right coronary artery crossed over the intracardiac mass. The mass, which was 3 cm × 2.5 cm × 2 cm in size, was completely excised. When the mass was cut open, it showed a solid content dark red in color (Figure 5). Quick freezing pathology indicated that the intracardiac mass was a malignant mesenchymal tumor, and a hemangiosarcoma could not be excluded. The combination of immunohistochemistry results and final pathology results demonstrated that the intracardiac mass was a cardiac paraganglioma. Given the patient’s history of surgery for bilateral carotid hemangioma in 2003 and 2018, we considered whether this hemangioma could also be a paraganglioma. On magnetic resonance imaging, an obvious mass in the left neck was observed. Immunohistochemistry demonstrated the following parameters: Synaptophysin (positive), chromogranin A (positive), Ki67 (3% positive), CD56 (positive), S100 (positive), CD34 (vascular positive), and epithelial membrane antigen (negative) (Figure 6). The combination of pathology and immunohistochemistry results demonstrated that the bilateral carotid masses were also paragangliomas.

Multiple paragangliomas of the heart and neck without hypertension.

None.

At the 3-mo follow-up, the patient did not experience recurrence of chest pain.

The incidence of paraganglioma is approximately 6 cases per 1000000 person-years. This rare disease can be lethal if undiagnosed. Thus, quick recognition is very important[1,2]. Both pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma can secrete catecholamines, and although they cannot be differentiated based on histology, they can be differentiated on anatomical location. Pheochromocytoma is an adrenal tumor, and paraganglioma is an extra-adrenal tumor[3]. The clinical presentation of paraganglioma is dependent on the symptoms caused by local invasion and/or hypersecretion of catecholamines. Cardiac paragangliomas are found in 0.05%-0.2% of patients who have hypertension[4]. The classic symptoms are the triad of headaches, palpitations, and profuse sweating. Anxiety and panic attacks are also common. Cardiac paragangliomas can also be asymptomatic.

To our knowledge, this is the first case of multiple paragangliomas of the heart and neck without hypertension. As this patient had multiple tumors (bilateral carotid artery and cardiac paraganglioma), it was necessary to determine whether they were multiple benign tumors or metastatic malignant tumors. Paraganglioma is generally considered a benign tumor and in most instances cured by complete excision. The only sure and undeniable sign of malignant behavior is demonstration of metastases. The updated World Health Organization classification of endocrine tumors has replaced the term “malignant paraganglioma” with “metastatic paraganglioma”[5]. Metastases are located where chromaffin tissue is normally not found (e.g., lymph nodes, lung, liver, and bones), and frequently, metastases are not confirmed histologically but are instead documented on nuclear imaging[6]. With regard to the biological behavior of this tumor, the right carotid artery paraganglioma did not recur for over 10 years, and previous reports have revealed that the Ki67 expression in malignant paraganglioma in the immunohistochemistry was higher than 5%[7]. The present patient’s Ki67 expression in the cardiac and bilateral carotid masses was lower than 5%, which was determined both in our hospital and in a local hospital in Shanghai. The patient’s symptoms were cured by complete excision of the paraganglioma, and we had already done the positron emission tomography/CT to exclude the distant metastases. Thus, we considered that the biological behavior of this cardiac paraganglioma was benign.

The reason for this patient’s chest pain was the direct toxicity of catecholamine. A previous paper demonstrated that hypersecretion of catecholamine and its oxidation products can cause coronary vasospasm, enhanced lipid metabolism, disorders of energy metabolism, changes in cell membrane permeability, and intracellular calcium overload, inducing chest pain, cardiac dilatation, and malignant arrhythmia[8].

Based on this patient’s history, physical examination, laboratory data, and radiological findings, the common causes of chest pain including acute myocardial infarction, aortic dissection, and pulmonary embolism were excluded. On the other hand, the patient’s chest pain was not typical of coronary artery disease, as his pain was not related to activity, usually lasted for hours, and CAG did not reveal significant coronary artery stenosis. Therefore, coronary atherosclerotic heart disease was excluded. Coronary artery aneurysm is common in coronary atherosclerotic heart diseases. However, CAG did not reveal coronary artery aneurysm, and the diagnosis of coronary artery aneurysm was excluded. Coronary arteriovenous fistula can also cause chest pain, but this disease is a rare congenital heart defect caused by abnormal cardiovascular development in the embryonic period. This patient did not have a history of congenital heart disease, heart auscultation revealed no murmur, and CAG did not reveal coronary arteriovenous fistula. Thus, the diagnosis of coronary arteriovenous fistula was also excluded.

With regard to treatment, surgical resection can significantly reduce the levels of catecholamines and improve hormone-related symptoms[9]. Surgical resection should be the first treatment option for cardiac paraganglioma.

We report a very rare case of multiple paragangliomas of the heart and bilateral carotid artery. This is a very rare disease and can be lethal if undiagnosed. Thus, quick recognition is very important. The key to the diagnosis of cardiac paraganglioma is the presence of typical symptoms, including headaches, palpitations, profuse sweating, hypertension, and chest pain. Radiology can demonstrate intracardiac masses. It is important to determine the levels of normetanephrine in the blood. The detection of genetic mutations is also recommended. Surgical resection is necessary to treat the disease and obtain pathological evidence.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kung WM S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Neumann HPH, Young WF Jr, Eng C. Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:552-565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 379] [Article Influence: 63.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Berends AMA, Buitenwerf E, de Krijger RR, Veeger NJGM, van der Horst-Schrivers ANA, Links TP, Kerstens MN. Incidence of pheochromocytoma and sympathetic paraganglioma in the Netherlands: A nationwide study and systematic review. Eur J Intern Med. 2018;51:68-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Karabinos I, Rouska E, Charokopos N. A primary cardiac paraganglioma. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Neumann HP. Pheochromocytoma. In: Jameson JL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Loscalzo J. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. 20th ed. New York: McGraw Hill Education; 2018: 2739-2746. |

| 5. | Lloyd RV, Osamura RY, Klöppel G, Rosai J. Phaechromocytoma. In: WHO classification of tumours of endocrine organs. 4th ed. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2017: 183-190. |

| 6. | Timmers HJ, Chen CC, Carrasquillo JA, Whatley M, Ling A, Havekes B, Eisenhofer G, Martiniova L, Adams KT, Pacak K. Comparison of 18F-fluoro-L-DOPA, 18F-fluoro-deoxyglucose, and 18F-fluorodopamine PET and 123I-MIBG scintigraphy in the localization of pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:4757-4767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 295] [Cited by in RCA: 277] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Taïeb D, Kaliski A, Boedeker CC, Martucci V, Fojo T, Adler JR Jr, Pacak K. Current approaches and recent developments in the management of head and neck paragangliomas. Endocr Rev. 2014;35:795-819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Behonick GS, Novak MJ, Nealley EW, Baskin SI. Toxicology update: the cardiotoxicity of the oxidative stress metabolites of catecholamines (aminochromes). J Appl Toxicol. 2001;21 Suppl 1:S15-S22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Strajina V, Dy BM, Farley DR, Richards ML, McKenzie TJ, Bible KC, Que FG, Nagorney DM, Young WF, Thompson GB. Surgical Treatment of Malignant Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma: Retrospective Case Series. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:1546-1550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |