Published online Nov 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i22.5645

Peer-review started: May 22, 2020

First decision: September 14, 2020

Revised: September 16, 2020

Accepted: September 25, 2020

Article in press: September 25, 2020

Published online: November 26, 2020

Processing time: 186 Days and 22.9 Hours

A rectoseminal vesicle fistula (RSVF) is a rare complication after anterior or low anterior proctectomy for rectal cancer mainly due to anastomotic leakage (AL). Limited literature documenting this rare complication is available. We report four such cases and review the literature to investigate the etiology, clinical manifestations, and the diagnostic and treatment methods of RSVF in order to provide greater insight into this disorder.

Four cases of RSVF were presented and summarized, and a further 12 cases selected from the literature were discussed. The main clinical symptoms in these patients were pneumaturia, fever, scrotal swelling and pain, anal pain, orchitis, diarrhea, dysuria, epididymitis and fecaluria. Imaging methods such as pelvic X-ray, computed tomography (CT), sinus radiography, barium enema and other techniques confirmed the diagnosis. CT was the imaging modality of choice. In cases presenting with reduced levels of AL, minimal surrounding inflammation, and controlled infection, the RSVF was conservatively treated by urethral catheterization, antibiotics administration and parenteral nutrition. In cases of severe RSVF, incision and drainage of the abscess or fistula and urinary or fecal diversion surgery successfully resolved the fistula.

This study provides an extensive analysis of RSVF, and outlines, summarizes and examines the causes, clinical manifestations, diagnostic procedures and treatment options, in order to prevent misdiagnosis and treatment errors.

Core Tip: A rectoseminal vesicle fistula (RSVF) is a rare complication after anterior or low anterior proctectomy for rectal cancer mainly due to anastomotic leakage. Four cases of RSVF were presented and summarized, and additional12 cases selected from the literature were reviewed and discussed. This study provides an extensive analysis of RSVF, and outlines, summarizes and examines the causes, clinical manifestations, diagnostic procedures and treatment options, in order to prevent misdiagnosis and treatment errors.

- Citation: Xia ZX, Cong JC, Zhang H. Rectoseminal vesicle fistula after radical surgery for rectal cancer: Four case reports and a literature review. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(22): 5645-5656

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i22/5645.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i22.5645

According to a report from the United States, the incidence of colorectal cancer (CRC) ranks third of all malignant tumors[1]. Rectoseminal vesicle fistula (RSVF) is a rare complication after invasive surgery, which is different from urethral fistulas such as rectal ejaculatory duct fistula[2], rectovesical fistula[3,4], colovesical fistula[5-7], prostato-rectal fistula[8] and coloseminal vesicle fistula[9,10]. There have been 10 relevant articles which reported a total of 12 cases of RSVF worldwide since 1989[11-20]. Among the various etiologies of RSVF such as prostatectomy[14], and transrectal seminal vesicle (SV) puncture drainage[16], the most common etiology is delayed emergence of anastomotic leakage (AL) following anterior resection (AR) or low anterior resection (LAR) for rectal surgery[11-13,15,17,19,20]. This study details four cases of RSVF from two surgical teams at the CRC Surgery Department between January 2009 and January 2019.

This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University (2017PS301K). Written informed consent was obtained from each patient. All patients were treated without chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Due to underlying diseases and economic reasons, patients 2 and 3 refused preoperative neoadjuvant therapy and protective ileostomy, and relevant agreements were signed. The patients were followed-up until May 2020 by clinical visit or by telephone. The follow-up period ranged from 8 to 88 mo after the first operation.

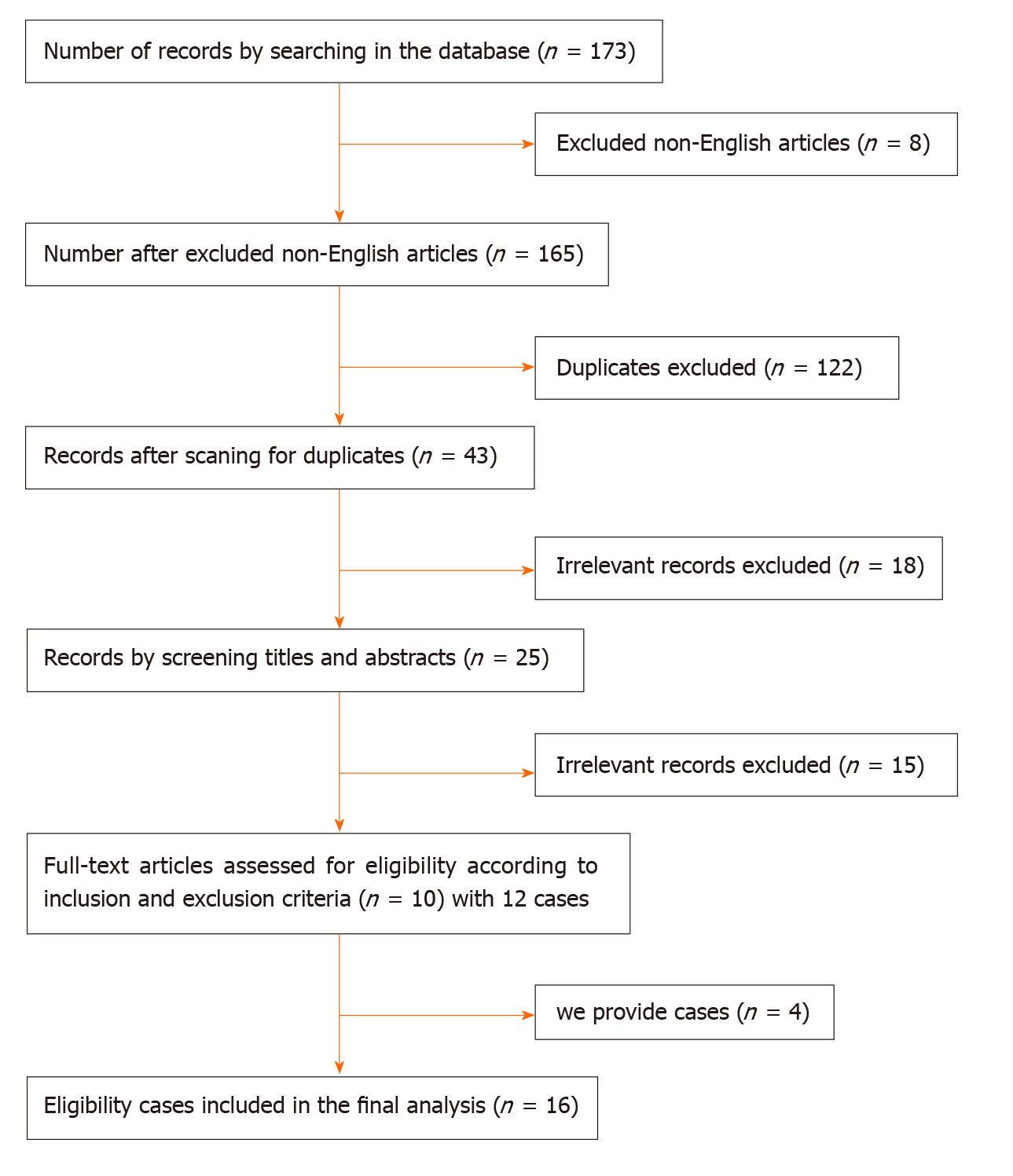

We conducted a comprehensive review of the literature from PubMed, EMBASE, Ovid and Springer published in English before May 2020. The following key words were used to identify articles: Rectoseminal vesicle fistula, recto-seminal vesicle fistula, rectal seminal vesicle fistula, and seminal vesicle rectal fistula. We also reviewed the bibliographies of relevant articles to identify additional studies. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients with rectal SV fistula; and (2) Acceptance of open or laparoscopic rectal cancer radical surgery. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients with colonic SV fistula; and (2) No detailed case information. The flow chart of the screened cases is shown in Figure 1.

Patients in two surgical treatment groups underwent a total of approximately 8000 CRC radical operations, and the incidence of AL was 2%-3% within ten years. This study detailed four cases of RSVF with an incidence of 2.02% secondary to AL following AR or LAR for rectal cancer between July 2013 and January 2019. The clinical data of 12 reviewed cases are summarized in Table 1 (No. 1-12), while the therapeutic and prognostic information of the additional four cases are shown in Table 1 (No.13-16).

| No. | Ref. or case | Patient age (yr) | Etiology | Symptoms | Diagnostic methods | Initial treatment | Re-treatment | ||

| Methods | Effects | Methods | Effects | ||||||

| 1 | Goldman et al[11] | 76 | LAR, AL, diarrhea associated with antibiotic | Pneumaturia, orchitis, urinary tract infection, diarrhea | Sinus radiography, barium enema | Catheterization, anti-inflammatory, sinus incision and drainage | Improved | ||

| 2 | Kollmorgen et al[12] | 32 | LAR, pelvic abscess | Fever, dysuresia | Suspicious symptoms | APR (fecal diversion), incision and drainage of subcutaneous abscess | Failure | Anti-inflammatory | Cured |

| 3 | Carlin et al[13] | 64 | AR | Fever | CT + rectal contrast | Abscess drainage | Failure | APR (fecal diversion) | Cured |

| 4 | Calder[14] | NS | Prostatectomy | NS | Barium enema | NS | NS | ||

| 5 | Roupret et al[15] | NS | Rectal cancer invaded seminal vesicle, LAR, pelvic abscess | Epididymitis, orchitis | CT | Anti-inflammatory, proctectomy, abscess drainage | Cured | ||

| 6 | Hammad[16] | NS | Transrectal seminal vesicle puncture drainage | Fever, anal pain | NS | Perianal drainage | Cured | ||

| 7 | Sýkora et al[17] | 66 | Laparoscopic AR | Pneumaturia, fever, epididymitis, scrotal swelling and pain | CT | Catheterization, anti-inflammatory, suprapubic cystostomy (urinary diversion) | Failure | Anti-inflammatory | Cured |

| 8 | Izumi[18] | 74 | NS | Pneumaturia, fever, orchitis,, scrotal swelling | Cystography | Bilateral scrotal drainage | Cured | ||

| 9 | Nakajima et al[19] | 73 | LAR, AL | Pneumaturia, fever, orchitis | CT, sinus radiography | Catheterization, anti-inflammatory | Cured | ||

| 10 | Nakajima et al[19] | 76 | LAR, water sac was not aspirated when removing ureter | Pneumaturia, orchitis,, scrotal swelling | CT, barium enema | Catheterization, anti-inflammatory | Failure | Fecal diversion | Cured |

| 11 | Nakajima et al[19] | 49 | LAR, AL | Fever, fecaluria | Ejaculatory duct radiography | Catheterization, anti-inflammatory, drainage of pelvic abscess, | Failure | Urinary + fecal diversion | Improved |

| 12 | Kitazawa et al[20] | 53 | LAR, AL, diarrhea associated with antibiotic | Pneumaturia, fever, diarrhea, cystitis | CT | Anti-inflammatory, parenteral nutrition | Cured | ||

| 13 | Case 1 | 64 | LAR, AL | Fever, diarrhea, dysuresia, pneumatinuria, epididymitis, scrotal swelling, orchitis, anal abscess | CT | Catheterization, anti-inflammatory, parenteral nutrition drainage of pelvic abscess, incision and drainage of epididymal abscess | Failure | Fecal diversion, incision and drainaging perianal abscess | Cured |

| 14 | Case 2 | 69 | Laparoscopic AR, AL | Pneumatinuria, scrotal swelling, hematochezia, anal pain | CT, MRI, Urethral retrograde urography | Fecal diversion, Catheterization, anti-inflammatory | Cured | ||

| 15 | Case 3 | 74 | Laparoscopic LAR, AL | Fever, abdominal pain, scrotal swelling, pneumatinuria, fecaluria, dysuresia | CT | Catheterization, anti-inflammatory | Cured | ||

| 16 | Case 4 | 49 | LAR, AL | Diarrhea, anal pain, pneumatinuria | CT | Catheterization, anti-inflammatory | Failure | Fecal diversion, anastomotic stenosis | Cured |

Case 1: A 64-year-old man developed symptoms of fever, with a maximum temperature of 38.5°C and stool frequency of 7-8 /d on postoperative day (POD) 5. Fecal residue due to AL was observed in the intrapelvic drainage tube.

Case 2: A 69-year-old man developed symptoms of pneumaturia, left scrotal swelling, hematochezia and anal pain on postoperative month (POM) 5 which gradually became worse.

Case 3: Abdominal swelling and pain, fever and abnormal characteristics of the intrapelvic drainage tube with an average of 15-30 mL feces appeared on POD 3 in a 74-year-old man. His abdominal pain intensified and new symptoms of left scrotal swelling and urine turbidity emerged on POD 4.

Case 4: Urinary retention and diarrhea with 10–20 stools/d developed on POD 17 and POD 20, respectively, in a 49-year-old man. Physical examination revealed slight anastomotic stenosis, right anterior wall AL approximately 2 cm from the anal verge, local tissue hardness and positive tenderness.

Chest, abdominal and head X-rays and computed tomography (CT) scans showed no distant metastases. Open LAR was performed in case 1 and case 4, while laparoscopic AR was carried out in the other two cases with additional ileostomy in case 3. The patients, irrespective of open or laparoscopic proctectomy, all underwent end-to-end anastomosis using a stapler.

Case 3 had coronary heart disease for ten years. The remaining cases had no history of past illness.

None of the patients had a history of drug allergies or genetic diseases.

The average tumor diameter in these four patients was 4.5 cm, and the distance from the anal margin ranged from 4 cm to 8 cm. With the exception of case 2 with right wall tumor, the tumor was located in the anterior wall in the other three patients.

AL in case 1 was locally restricted, and culture for blood bacteria and fungi was negative. All patients had different degrees of elevated white blood cells.

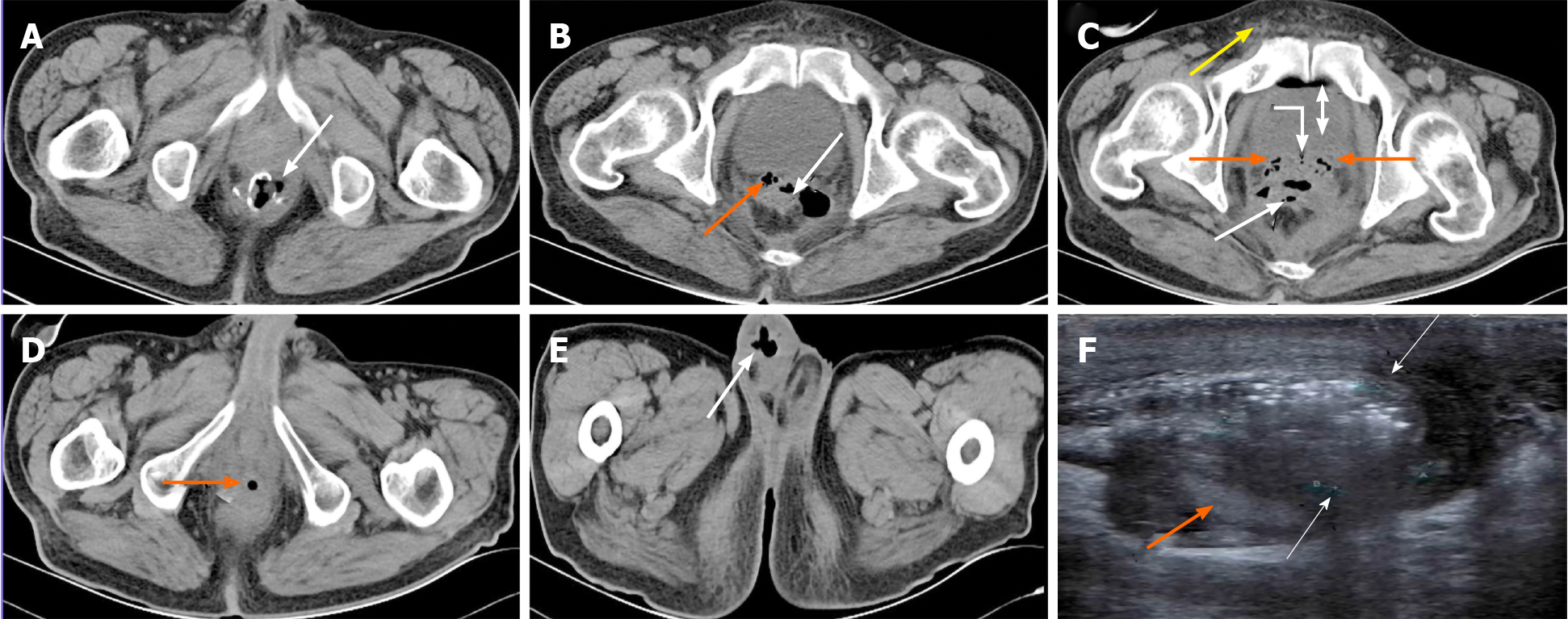

Case 1: Pelvic CT revealed RSVF secondary to AL following LAR, air bubbles were seen to enter the ejaculatory duct opening of the urethral prostate caruncle due to direct infection, and the bladder along the posterior urethra and the scrotum along the deferent duct showed retrograde infection on POD 21 (Figure 2A-E). Urinary system color Doppler ultrasound diagnosed a right epididymis tail abscess, epididymitis and scrotal edema (Figure 2F).

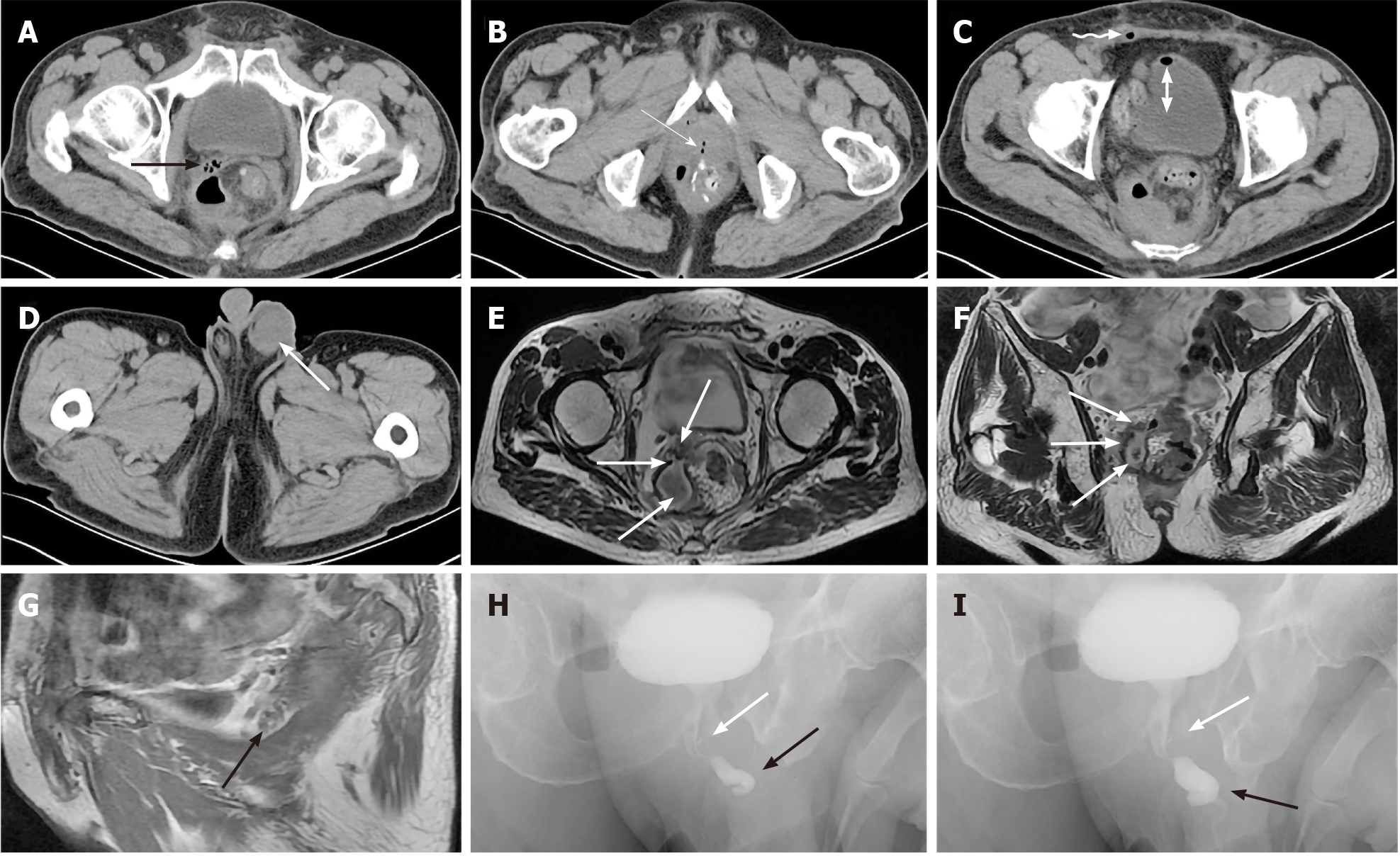

Case 2: Colonoscopy revealed local inflammatory edema and leakage of anastomoses, while cystoscopy showed no obvious abnormalities. However, CT demonstrated a pelvic pus cavity and a left scrotal abscess secondary to AL after proctectomy (Figure 3A-D). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) diagnosed a sinus from a pelvic encapsulated abscess to the SV associated with rectal AL (Figure 3E-G). Urethral retrograde urography demonstrated contrast agent retrogradely entering the ejaculatory duct from the ejaculatory duct opening of the urethral prostate caruncle (Figure 3H and I).

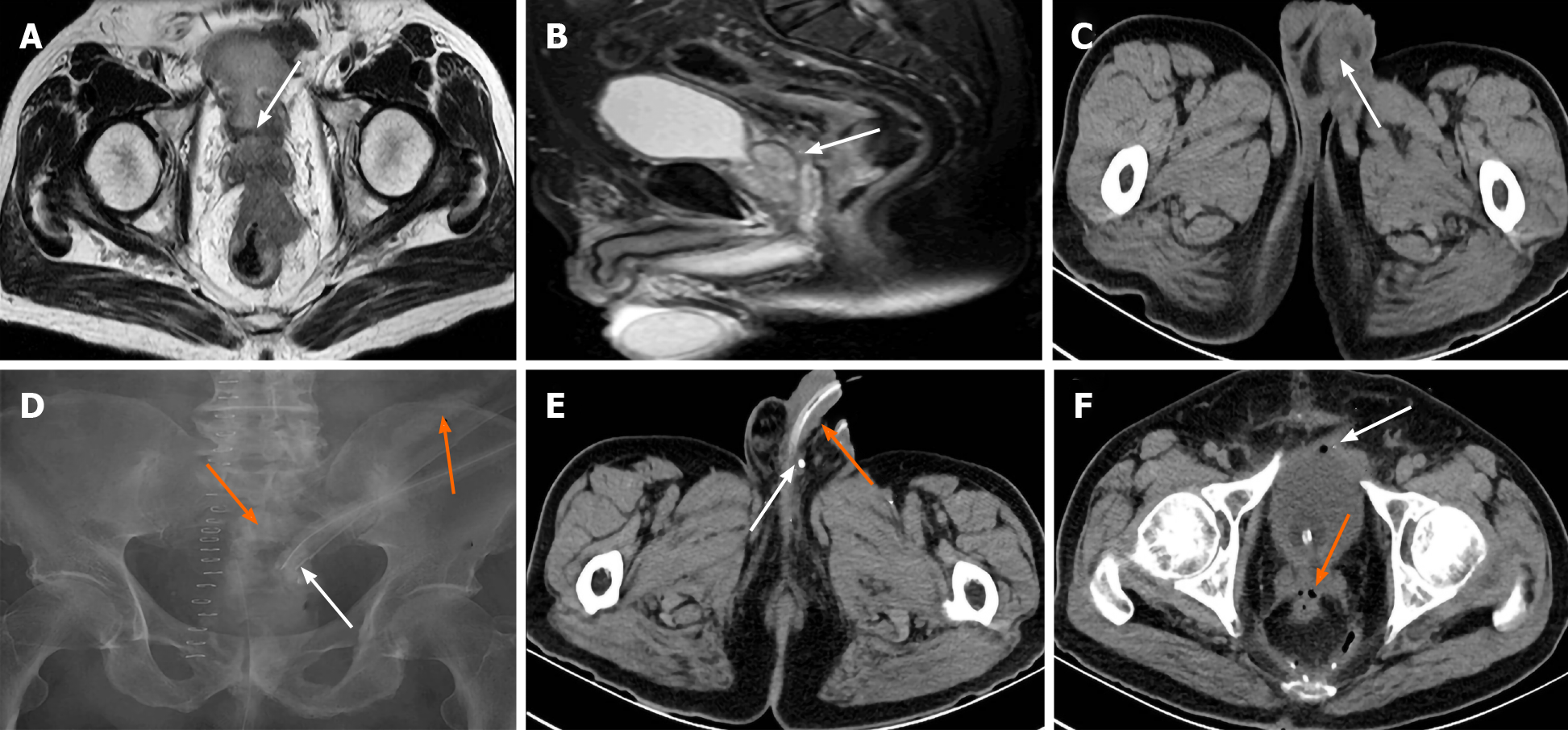

Case 3: Preoperative MRI in case 3 revealed penetration of the rectal front wall by the large tumor including the full thickness of the rectal layers and invasion of Denonvilliers’ fascia (DF) at the level of the SV (Figure 4A and B). The left swollen and infected scrotum was revealed by postoperative CT (Figure 4C). Transabdominal sinus radiography identified rectal AL but not urethral leakage (Figure 4D). RSVF was identified by CT when contrast agent was seen to retrogradely enter the ductus deferens around the entrance to the epididymis (Figure 4E) and air bubbles in the SV and bladder via the sinus secondary to AL (Figure 4F).

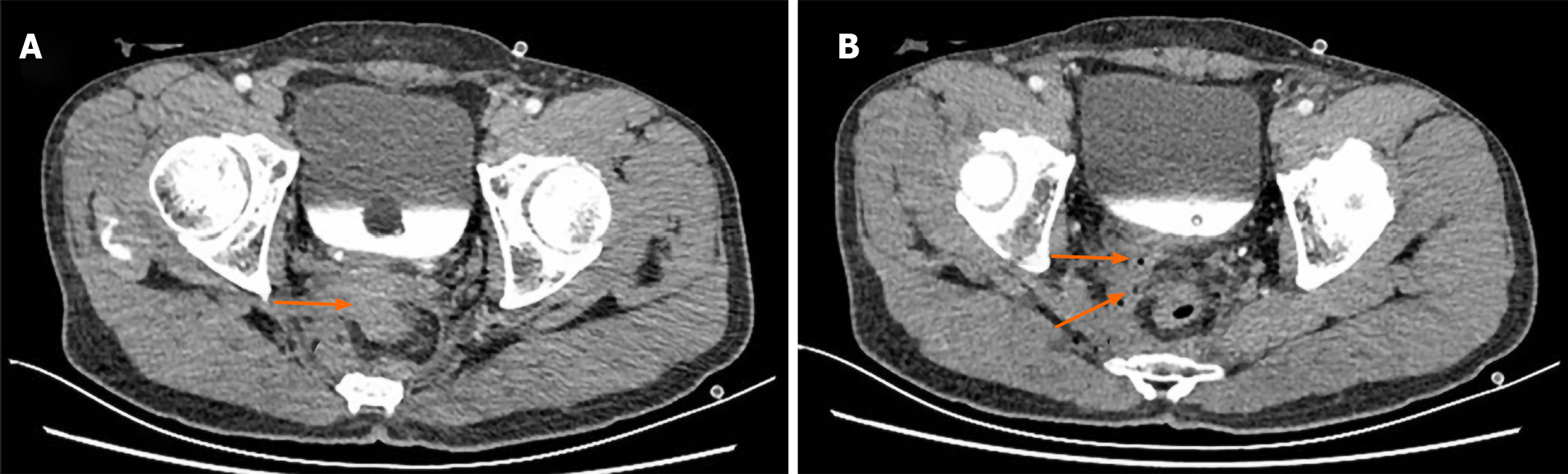

Case 4: Pelvic CT scan, sinus radiography, cystoscopy and transurethral retrograde angiography showed no obvious sinus; however, rectovesical fistula was excluded. Pelvic enhanced CT revealed a fistula between the right SV and the rectal anastomotic site, and air bubbles located within the right SV, which confirmed RSVF secondary to AL (Figure 5A and B).

Case 1: RSVF, AL, right epididymis tail abscess. Case 2: RSVF, AL, left scrotal abscess. Case 3: RSVF, AL. Case 4: RSVF, AL.

Case 1: The patient was treated with lavage via an intrapelvic drainage tube, parenteral nutrition, anti-inflammatory and anti-diarrheal therapy as conservative treatment. Due to gradual development of dysuria, pneumaturia, testicular pain, scrotal swelling and intermittent fever with the highest temperature of 39°C, urethral catheterization with a saline flush was performed on POD 17. The most severe urinary tract symptoms appeared on POD 33 to 44. The patient continued with urethral catheterization and underwent surgery for incision and drainage of the right epididymis abscess and colostomy or ileostomy for fecal diversion on POD 45. The patient began to drink a small amount of water and gradually increased the amount of water to increase urine volume and reduce the risk of urinary tract infection. Pneumaturia and frequent defecation gradually improved to 2 times/d and 4-5 stools/d, respectively, on POD 68. The previous conservative treatment was continued and partial enteral nutrition was increased. The fistula had disappeared by POD 120. The catheter was removed, oral feeding was conducted, and intestinal traffic continuity was restored. A chemotherapy regimen which included oxaliplatin and fluorouracil was given twice and terminated due to side effects. The patient experienced repeated perianal discharge at POM 10 and a perianal abscess was diagnosed by pelvic CT. Stool frequency gradually increased with a maximum frequency of 30 /d. Conservative treatment was continued for a further 10 mo and the patient still experienced serious symptoms. Finally, in view of the risk of AL and stenosis after stoma, the patient requested resection of the rectal anastomosis (Hartmann operation), a permanent colostomy for defecation and incision and drainage of the perianal abscess were performed to replace the temporary lateral ileostomy or colostomy. The leakage was successfully healed at POD 10 after the second operation. Chemotherapy was administered a further 3 times.

Case 2: Anti-inflammatory therapy with broad-spectrum antibiotics and urethral catheterization gradually improved anal pain and pneumaturia, and AL and RSVF resolved on POM 10. CT revealed right SV and left deferent duct stones without symptoms secondary to RSVF (Supplementary Figure 1).

Case 3: Lavage via an intrapelvic drainage tube with 250/500 mL normal saline flush and negative pressure, anti-inflammation with a broad-spectrum antibiotic (metronidazole) once/d and enteral nutrition, were administered to improve symptoms, while moxifloxacin was added once/d for unimproved urinary tract symptoms, e.g. left scrotal edema and pneumaturia which emerged on POD 12 and fecaluria on POD 14, respectively. Enteral nutrition was replaced by normal eating and urethral catheterization was removed when symptoms of dysuria, pneumaturia, and fecaluria disappeared, scrotal edema was alleviated, and pelvic drainage decreased to approximately 5 mL/d without obvious abscess and feces on POD 20. After 3 d, dysuria and urinary infection reappeared without fever, and a continuous daily moxifloxacin flush via the intrapelvic drainage tube was administered with obvious effect, which continued until POD 30. Healing of the fistula was confirmed and stoma closure was eventually performed on POM 7.

Case 4: Urethral catheterization, anti-inflammatory and anti-diarrheal drugs were given but had no effect following gradually aggravated anal pain and pneumaturia. As this conservative treatment did not improve the patient’s condition, the patient finally underwent ileal protective stoma with fecal diversion and anastomotic stenosis dilatation on POD 74 with a gradual improvement in symptoms. Stoma closure was performed on POM 8.

The first three cases had moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma, and the fourth case had well differentiated adenocarcinoma. TNM stages were T2N0M0, T3N0M0, T3N2M0 and T2N0M0, respectively.

Case 1: Follow-up was continued until the 50th month after the first operation and no recurrence or metastasis was observed on whole body positron emission tomography .

Case 2: The patient is still alive without local recurrence 75 mo after the first operation.

Case 3: The patient is still alive without recurrence or metastasis 8 mo after surgery.

Case 4: The patient is still alive without local recurrence or distant metastasis 88 mo after the first operation.

In the analysis of the 12 cases from the literature and the present 4 new cases, RSVF developed after proctectomy (12/16), with 75% following LAR and 25% following AR, after resection of the prostate (1/16), after an invasive operation (1/16), for direct tumor invasion (1/16) and for an unknown cause (1/16). The tumors including 13 well/moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma and a giant polyp with severe atypical hyperplasia and 2 unclear cases, were 4–11 cm from the anal verge. The shortest onset time was POD 3, most of which occurred within one month, while the longest onset time was POM 6. The main clinical manifestations included fever (10/16), pneumaturia (10/16), scrotal swelling and pain (6/16), anal pain (5/16), orchitis (5/16), diarrhea (4/16), dysuria (3/16), epididymitis (2/16), and fecaluria (2/16). Occasionally, urinary tract infection, abdominal pain, hematuria, abnormal sperm, and cystitis were observed. Most RSVFs in these 16 cases were identified by CT including enhanced CT and CT with rectal contrast imaging (10/16), barium enema (3/16), sinus radiography (2/16), and occasionally by cystoscopy, urethral retrograde urography, MRI, ejaculatory duct radiography, and due to clinical symptoms and experience. All imaging examinations had different diagnostic significance, but that of CT, was highest. In total, 4 of the 16 patients were cured by conservative therapy, 4 cases improved or were healed by conservative therapy plus abscess or fistula incision and drainage, 9 cases were cured by colostomy or ileostomy after failed treatment (a temporary protective ileostomy was performed during the first operation in case 3), 2 cases with severe infection underwent urinary and fecal diversions combined with long-term postoperative anti-infection therapy, and in 1 case treatment was unclear.

With advancement in surgical techniques after removal of the rectum and in surgical instruments, the rate of anal preservation has improved, and visualization of the local anatomic structures during surgery has been refined. However, the rate of urinary system complications, which are still difficult to eradicate during proctectomy, is approximately 1.5%–3.0%[21,22]. It is essential to identify and diagnose RSVF as a urethral-related injury in patients who still have temporary urethral symptoms such as scrotal swelling, epididymitis, and orchitis after rectal surgery.

The etiology of RSVF in the four cases presented in this study was analyzed. First, RSVF mainly occurs due to AL. Fecal material accompanied by infectious substances contaminate and damage the tissues surrounding the anastomotic fistula, which gradually penetrate the adjacent exposed SV to form a fistula. Second, during radical proctectomy with total mesorectal excision (TME) as the gold standard[23,24], DF or anterior rectal fascia, which is the natural barrier for the forward invasion of rectal tumors and the anterior boundary for TME in AR or LAR[25], is separated between the anterior wall of the rectum and the peritoneum at the bottom of the posterior bladder wall, down to the demarcation line between the prostate, the SV and the rectum, and even to the pelvic floor and levator ani muscle level. The circumferential margin (CRM) is also a major predictor of survival after surgery or neoadjuvant therapy for rectal cancer[26]. The tumor in our case 3 was located in the anterior wall of the rectum, and it was necessary to ensure a sufficient and safe CRM, which may result in the SV membrane being thinner and even damaged. Inflammation around the fistula more easily affects the SVs with no protection of DF to form the RSVF[11]. One case with a large rectal adenocarcinoma invading the right SV was treated with bilateral SV resection; however, it is difficult to precisely ligate the bottom of the SV. Postoperative AL leads to local abscess invading the opening of the ejaculatory duct[19]. Third, long-term and repeated urethral catheterization increases the risk of urinary tract infection due to chronic compression of the ejaculatory tube opening of the urethral prostate and causes local inflammation and ischemia. Finally inflammation retrogradely affects the SVs causing vesiculitis and a fistula. In addition, antibiotic-related intractable diarrhea[8] inducing AL, particularly in the anastomotic stoma only 2–3 cm from the anal verge, is another etiology of RSVF.

The onset time is mainly determined by the size of the AL, the progress of inflammation and the time of infection invading the SV. In case 1 and case 3, we observed the number and severity of symptoms due to early-onset and obvious AL with inflammation invading the urethra (anterograde direction) and deferent duct (retrograde direction), in contrast to case 2 and case 4 who had relatively few and slight symptoms owing to occult and late-onset AL. The clinical symptoms can be divided into 3 parts. First, the main symptoms are fever, pneumaturia, fecaluria, and dysuria, as a result of a small amount of gas entering the SV along the narrow sinus and discharging into the urethra via the ejaculatory duct and its opening in the urethral prostatic caruncle. If the fistula is obvious, part of the fecal residues enter the sinus causing fecaluria. Inflammation stimulates the bladder causing edema and dysuria. Second, the gases, feces, infective necrotic materials and semen can reverse into the deferent duct and epididymis causing orchitis, epididymitis[9], scrotal pain, and even an abscess[13]. Third, the main symptoms are diarrhea and anal pain, related to low anastomosis and AL.

Each patient has specific requirements due to their individual differences; hence, the diagnostic methods vary. When combined with clinical symptoms and the characteristics of intrapelvic drainage tubes, pelvic CT scan and contrast-enhanced CT had a high diagnostic rate as they clearly showed the fluid and air bubbles around the AL, and identified the sinus between the fistula of rectal anastomosis and infected SV. Of course, MRI can be performed due to its advantages in displaying complicated leakages[27]. Case 2 experienced symptoms of hematochezia; therefore, we used urethral retrograde urography to detect the small amount of contrast agent retrogradely entering the opening of the ejaculatory duct in the urethral prostate, after CT scanning indicated bubbles in the ejaculatory duct and deferent duct. The rectal fistula draining the sinus and port are usually straighter and wider than that of the spermaduct and ejaculatory duct; thus, transrectal venography (e.g., barium enema and sinus radiography) is usually easier than transurethral (e.g., urethral retrograde urography and cystoscopy). There was a right epididymal abscess and obvious infection in the testes, scrotum and epididymis in case 1. With the rapid development of ultrasound and endoscopy, it is worthwhile investigating transanal endoscopic ultrasonography (TEUS), which can successfully diagnose RSVF by scanning various layers of the rectum with an ultrasound probe. Coulier et al[21] reported that a SV-colonic fistula secondary to a sigmoid diverticulum resulted in emphysematous epididymitis, which was diagnosed by TEUS. The most noteworthy technique may be SV adenoscopy, according to reports[28,29], transurethral SV adenoscopy has been used in the diagnosis and treatment of SV diseases (such as SV stone, deposition, inflammation, tumor, ejaculatory duct cyst, hemospermia etc). Its application has been confirmed, but it is also expected to become a definite diagnostic and treatment method for RSVF. As multiple similar cases are diagnosed, sometimes with symptoms, we can diagnose the disease clinically.

The treatment of RSVF is divided into conservative treatment and surgical treatment. Conservative treatments include anti-inflammatory therapy with sensitive antibiotics, total parenteral nutrition, lavage via the intrapelvic drainage tube to reduce fecal contamination, urethral catheterization in order to decrease irritation and infection in the urinary system, and symptomatic treatment such as anti-diarrheal therapy. In case 2 who had an undiagnosed postoperative AL, this was manifested by various RSVF-related symptoms on POM 5. Due to minor AL, localized inflammation and unobstructed drainage, the patient recovered after conservative treatment. Elderly patients with severe primary disease and unable to tolerate surgical trauma, young patients who have fertility requirements, and those who do not accept colostomy or SV resection can attempt conservative treatment and uncomplicated incisional drainage. A complex sinus, deep location of the abscess, poor drainage, and severe local or systemic infection are the main causes of treatment failure.

In patients with serious AL, extensive infection and obvious urethral symptoms, conservative treatment alone is inadequate and suitable operations are required. Surgical treatments include sinus or abscess drainage, urinary diversion (e.g. suprapubic cystostomy, cutaneous ureterostomy etc.) and fecal diversion (e.g. colostomy, ileostomy etc.). If drainage via the intrapelvic tube is obstructed, the pus cavity is superficial and located near the skin, subcutaneous or sinus incision and drainage can be performed by the perianal or perineal route and are partly effective[11,15,16]. In addition, scrotal drainage[18], or epididymal abscess drainage due to retrograde deferent duct infection as in case 1 can be performed, respectively. Urine/fecal diversion seems to be necessary when drainage fails to relieve symptoms or cure RSVF with a success rate of 75%. After failed operations, some patients still require treatment with long-term anti-infection[12,16]. Sýkora et al[17] reported that some cases requiring urinary diversion can reduce intra-vesicle pressure and accelerate healing with suprapubic cystostomy. Although we have not attempted urinary diversion, our experience is to maintain the patency of the urinary tract until symptoms improved significantly following urethral catheterization. If the symptoms appear again, urethral catheterization is performed again. The incidence of AL after colorectal surgery varies greatly from 4% to 29.5%[30-33]. Whether enterostomy can prevent AL has always been a controversial hot topic[34,35]. However, fecal diversion can effectively prevent feces from continuing to aggravate the infection around the anastomosis, and the diet should be restored as soon as possible to enhance immunity and reduce the release of inflammatory factors[36]. The limitations of this study are that due to the small number of cases, it is not possible to provide a therapeutic regimen for this complication. Therefore, individualized treatment of RSVF is necessary.

The incidence of RSVF is much higher than reported as not enough is known about the disease. Four cases of RSVF that occurred as a complication due to AL after proctectomy along with a review of the literature of similar cases are discussed. This helped us to analyze the disease process and postulate various possible etiologies which will prompt further investigation and open new avenues for research to eventually enable the necessary preventative measures to be taken. Moreover, discussion and analysis of the treatment methods used will alert readers to the efficacy of the various imaging modalities and the conservative and surgical techniques used and in turn open up global discussion on this complication of AL after proctectomy. Thus, by analyzing this lesser-known complication and previous treatment experience, we have highlighted the diagnostic methods used for RSVF, to prompt effective and reasonable treatment to avoid misdiagnosis and mistreatment.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: De la Plaza Llamas R S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: MedE-Ma JY P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Anderson WF, Miller KD, Ma J, Rosenberg PS, Jemal A. Colorectal Cancer Incidence Patterns in the United States, 1974-2013. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 568] [Cited by in RCA: 828] [Article Influence: 103.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hamidinia A. Recto-ejaculatory duct fistula: an unusual complication of Crohn's disease. J Urol. 1984;131:123-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kiyasu Y, Kano N. Huge rectovesical fistula due to long-term retention of a rectal foreign body: A case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2017;31:163-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Manuel-Vázquez A, Jiménez-Miramón FJ, Ramos-Rodríguez JL, Jover-Navalón JM. Minimally invasive treatment of rectovesical fistula: A case report. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2016;108:164-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Siddiqui MR, Sanford T, Nair A, Zerbe CS, Hughes MS, Folio L, Agarwal PK, Brancato SJ. Chronic Colovesical Fistula Leading to Chronic Urinary Tract Infection Resulting in End-Stage Renal Disease in a Chronic Granulomatous Disease Patient. Urol Case Rep. 2017;11:37-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Salgado-Nesme N, Vergara-Fernández O, Espino-Urbina LA, Luna-Torres HA, Navarro-Navarro A. Advantages of Minimally Invasive Surgery for the Treatment of Colovesical Fistula. Rev Invest Clin. 2016;68:229-304. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Aydinli HH, Benlice C, Ozuner G, Gorgun E, Abbas MA. Risk factors associated with postoperative morbidity in over 500 colovesical fistula patients undergoing colorectal surgery: a retrospective cohort study from ACS-NSQIP database. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2017;32:469-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Xing L, Liu Z, Deng G, Wang H, Zhu Y, Shi P, Huo B, Li Y. Xanthogranulomatous prostatitis with prostato-rectal fistula: a case report and review of the literature. Res Rep Urol. 2016;8:165-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Coulier B, Ramboux A, Maldague P. Emphysematous epididymitis as presentation of unusual seminal vesicle fistula secondary to sigmoid diverticulitis: case report. Abdom Imaging. 2005;30:113-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Boulianne M, Bouchard G, Cloutier J, Bouchard A. Coloseminal vesicle fistula after low anterior resection: Report of a case and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;51:257-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Goldman HS, Sapkin SL, Foote RF, Taylor JB. Seminal vesicle-rectal fistula. Report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:67-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kollmorgen TA, Kollmorgen CF, Lieber MM, Wolff BG. Seminal vesicle fistula following abdominoperineal resection for recurrent adenocarcinoma of the rectum. Report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:1325-1327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Carlin J, Nicholson DA, Scott NA. Two cases of seminal vesicle fistula. Clin Radiol. 1999;54:309-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Calder JF. Seminal vesicle fistula. Clin Radiol. 2000;55:328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Roupret M, Varkarakis J, Valverde A, Sèbe P. Recto-seminal fistula and cancer of the rectum. Prog Urol. 2004;14:1219-1220. |

| 16. | Hammad FT. Seminal vesicle cyst forming an abscess and fistula with the rectum review of perianal drainage and treatment. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2006;40:426-428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sýkora R, Krhut J, Jonszta T, Němec D, Havránek O, Martínek L. Fistula between anterior rectum wall and seminal vesicles as a rare complication of low-anterior resection of the rectum. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne. 2012;7:63-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Izumi K. Seminal vesicle-rectal fistula with preceding right acute epididymitis. Urol Int. 2007;78:367-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Nakajima K, Sugito M, Nishizawa Y, Ito M, Kobayashi A, Nishizawa Y, Suzuki T, Tanaka T, Etsunaga T, Saito N. Rectoseminal vesicle fistula as a rare complication after low anterior resection: a report of three cases. Surg Today. 2013;43:574-579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kitazawa M, Hiraguri M, Maeda C, Yoshiki M, Horigome N, Kaneko G. Seminal vesicle-rectal fistula secondary to anastomotic leakage after low anterior resection for rectal cancer: a case report and brief literature review. Int Surg. 2014;99:23-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Stitt L, Flores FA, Dhalla SS. Urethral injury in laparoscopic-assisted abdominoperineal resection. Can Urol Assoc J. 2015;9:E900-E902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sawkar HP, Kim DY, Thum DJ, Zhao L, Cashy J, Bjurlin M, Bhalani V, Boller AM, Kundu S. Frequency of lower urinary tract injury after gastrointestinal surgery in the nationwide inpatient sample database. Am Surg. 2014;80:1216-1221. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Bjørn MX, Perdawood SK. Transanal total mesorectal excision--a systematic review. Dan Med J. 2015;62:A5105. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Vatandoust S, Price TJ, Karapetis CS. Colorectal cancer: Metastases to a single organ. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:11767-11776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 23.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 25. | Kim JH, Kinugasa Y, Hwang SE, Murakami G, Rodríguez-Vázquez JF, Cho BH. Denonvilliers' fascia revisited. Surg Radiol Anat. 2015;37:187-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kang BM, Park YK, Park SJ, Lee KY, Kim CW, Lee SH. Does circumferential tumor location affect the circumferential resection margin status in mid and low rectal cancer? Asian J Surg. 2018;41:257-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Nishimori H, Hirata K, Fukui R, Sasaki M, Yasoshima T, Nakajima F, Hata F, Kobayashi K. Vesico-ileosigmoidal fistula caused by diverticulitis: report of a case and literature review in Japan. J Korean Med Sci. 2003;18:433-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Zaidi S, Gandhi J, Seyam O, Joshi G, Waltzer WC, Smith NL, Khan SA. Etiology, Diagnosis, and Management of Seminal Vesicle Stones. Curr Urol. 2019;12:113-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Miao C, Liu S, Zhao K, Zhu J, Tian Y, Wang Y, Liu B, Wang Z. Treatment of Mullerian duct cyst by combination of transurethral resection and seminal vesiculoscopy: An initial experience. Exp Ther Med. 2019;17:2194-2198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Cheng S, He B, Zeng X. Prediction of anastomotic leakage after anterior rectal resection. Pak J Med Sci. 2019;35:830-835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Małek Z, Małek P, Dziki Ł. The influence of bowel preparation on postoperative complications in surgical treatment of colorectal cancer. Pol Przegl Chir. 2019;91:10-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Borstlap WAA, Westerduin E, Aukema TS, Bemelman WA, Tanis PJ; Dutch Snapshot Research Group. Anastomotic Leakage and Chronic Presacral Sinus Formation After Low Anterior Resection: Results From a Large Cross-sectional Study. Ann Surg. 2017;266:870-877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 23.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Wang S, Liu J, Wang S, Zhao H, Ge S, Wang W. Adverse Effects of Anastomotic Leakage on Local Recurrence and Survival After Curative Anterior Resection for Rectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. World J Surg. 2017;41:277-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Salamone G, Licari L, Agrusa A, Romano G, Cocorullo G, Falco N, Tutino R, Gulotta G. Usefulness of ileostomy defunctioning stoma after anterior resection of rectum on prevention of anastomotic leakage A retrospective analysis. Ann Ital Chir. 2016;87:155-160. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Mari FS, Di Cesare T, Novi L, Gasparrini M, Berardi G, Laracca GG, Liverani A, Brescia A. Does ghost ileostomy have a role in the laparoscopic rectal surgery era? Surg Endosc. 2015;29:2590-2597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Boelens PG, Heesakkers FF, Luyer MD, van Barneveld KW, de Hingh IH, Nieuwenhuijzen GA, Roos AN, Rutten HJ. Reduction of postoperative ileus by early enteral nutrition in patients undergoing major rectal surgery: prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2014;259:649-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |