Published online Nov 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i22.5603

Peer-review started: January 1, 2020

First decision: September 29, 2020

Revised: October 5, 2020

Accepted: October 19, 2020

Article in press: October 19, 2020

Published online: November 26, 2020

Processing time: 329 Days and 1.6 Hours

The prognosis of paediatric primary refractory/relapsed acute myeloid leukaemia (R/R AML) remains poor. Intensive therapy is typically used as salvage treatment for those with R/R AML. No data are currently available about the use of the CLAG-M protocol as salvage therapy in paediatric patients with R/R AML.

An 8-year-old patient was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukaemia by bone marrow morphology and immunophenotype. The patient showed poor response to two cycles of induction therapy with 60% blast cells in the bone marrow after the second induction cycle. The patient achieved complete remission after being treated with the CLAG-M protocol as salvage therapy before undergoing umbilical cord blood stem cell transplantation. Morphological complete remission with haematological recovery has hitherto been maintained over 4 mo. Abnormal gene mutations detected at diagnosis were undetectable after haematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Here we present a paediatric patient with primary refractory acute myeloid leukaemia who was successfully treated with the CLAG-M protocol. Given the positive results of the presented patient, large-scale clinical studies are required to assess the role of the CLAG-M protocol in the salvage treatment of refractory or relapsed AML in childhood.

Core Tip: The outcome of refractory/relapsed acute myeloid leukaemia (R/R AML) in childhood remains poor. A boy with primary refractory AML achieved complete remission (CR) after being treated with one cycle of the CLAG-M protocol as salvage therapy. Umbilical cord blood stem cell transplantation was carried out after CR. The patient remains in complete remission without previous genetic abnormalities. The CLAG-M protocol might be an effective and tolerable salvage regimen and a bridge to haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in R/R AML. Additionally, we focus our literature review on the role of cladribine-based protocols in paediatric and adult R/R AML patients.

- Citation: Huang J, Yang XY, Rong LC, Xue Y, Zhu J, Fang YJ. CLAG-M chemotherapy followed by umbilical cord blood stem cell transplantation for primary refractory acute myeloid leukaemia in a child: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(22): 5603-5610

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i22/5603.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i22.5603

The outcome of newly diagnosed paediatric acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) has markedly improved in past decades. The long-term survival of childhood AML has reached 70% with advances in first-line chemotherapy, haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) and supportive care[1]. Despite the impressive improvement in outcome, the prognosis of children with refractory/relapsed acute myeloid leukaemia (R/R AML) is still poor. There is no uniform salvage therapy for paediatric R/R AML. Intensified conventional therapy and new combinations have been used to achieve remission or second remission. Salvage treatment also serves as a bridge to HSCT.

Purine nucleoside analogue (PNA) combined with cytarabine (Ara-C) and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), such as in the fludarabine, Ara-C and G-CSF (FLAG) protocol, has been widely used in both paediatric and adult R/R AML. Cladribine (2-CdA, 2-chloro2’-deoxyadenosine) is one of PNAs approved for the treatment of haematological malignancies. Early clinical trials showed notable antileukaemic activity of cladribine used as a single agent in paediatric patients with R/R AML[2]. Because of the impressive results of initial trials in paediatric patients, the use of 2-CdA has expanded from a single drug to different combination regimens with other agents. Multiple studies of cladribine-based regimens have been carried out in adults with R/R AML. To date, the most promising 2-CdA-based protocols in adult patients have been CLAG (2-CdA, Ara-C and G-CSF) and its derivative regimen CLAG-M (2-CdA, Ara-C, G-CSF and mitoxantrone), which was first reported by the Polish adult leukaemia group (PALG)[3].

Data about the use of the CLAG-M protocol as salvage therapy in paediatric R/R AML is rarely available. We successfully treated a paediatric patient with primary refractory AML using the CLAG-M protocol followed by umbilical cord blood stem cell transplantation. This article discusses the clinical efficacy and toxicity of the CLAG-M protocol in refractory paediatric AML as salvage therapy. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of the patient, and the study was approved by our institutional ethics committee.

An 8-year-old boy was admitted to the Department of Haematology and Oncology, Children’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University because of fever and enlargement of cervical lymph nodes.

The patient’s symptom of fever started 5 d prior with gradually enlarged lymph nodes.

The patient had a free previous medical history.

The parents denied any special personal or family history of leukaemia or other disease.

Physical examination showed pallor, cervical lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly.

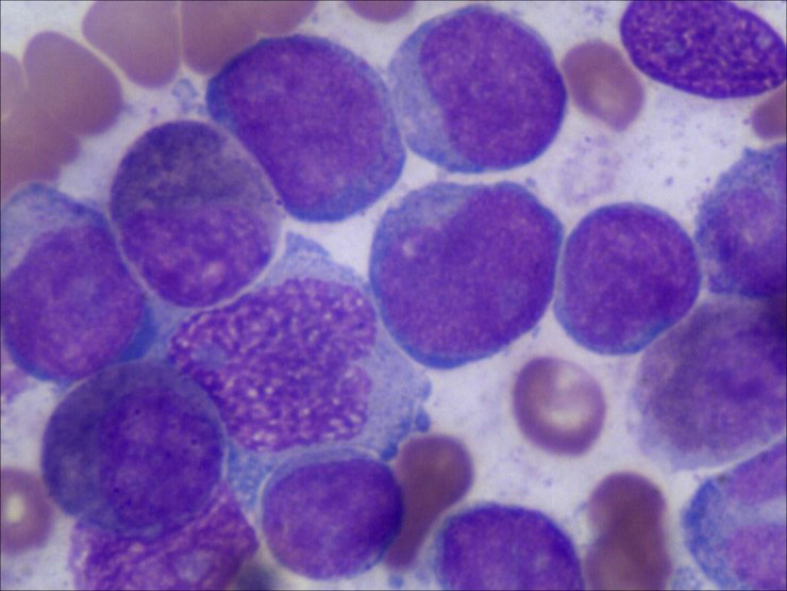

Peripheral blood count revealed hyperleukocytosis (white blood cell 103.8 × 109/L), anaemia (haemoglobin 74 g/L) and thrombocytopenia (platelets 56 × 109/L), while 70% blast cells were detected in peripheral blood smears with hypercellularity. Morphological examination of bone marrow aspirate showed 78% blast cells (Figure 1). Immunophenotypic analysis demonstrated that blast cells were positive for CD33 (96.70%), CD13 (57.55%), CD11b (18.20%), CD64 (19.00%), CD15 (31.70%), GPA (11.50%) and CD117 (85.10%). Normal karyotype, a heterozygous synonymous mutation (c.1107A>G) in exon 7 of the WT1 gene and a heterozygous missense mutation (c.37G>T) in the N-terminal codon 13 of the KRAS gene were observed by genetic analysis.

An initial imaging evaluation with computed tomography scan revealed cervical lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly.

The diagnosis of AML (M2) was established.

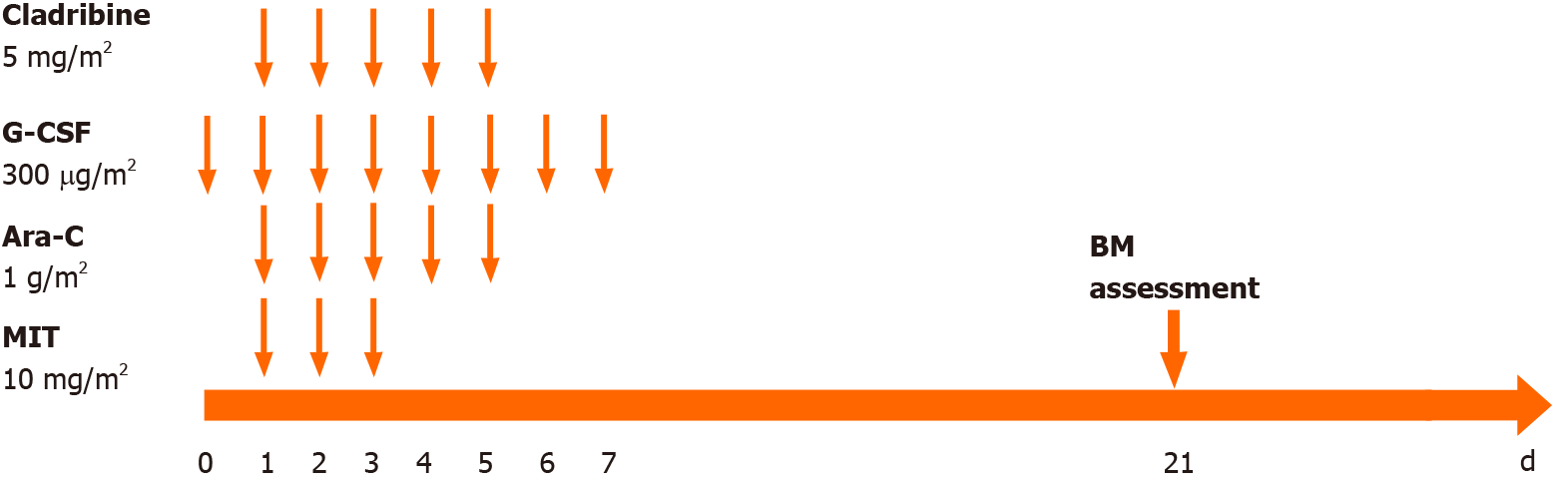

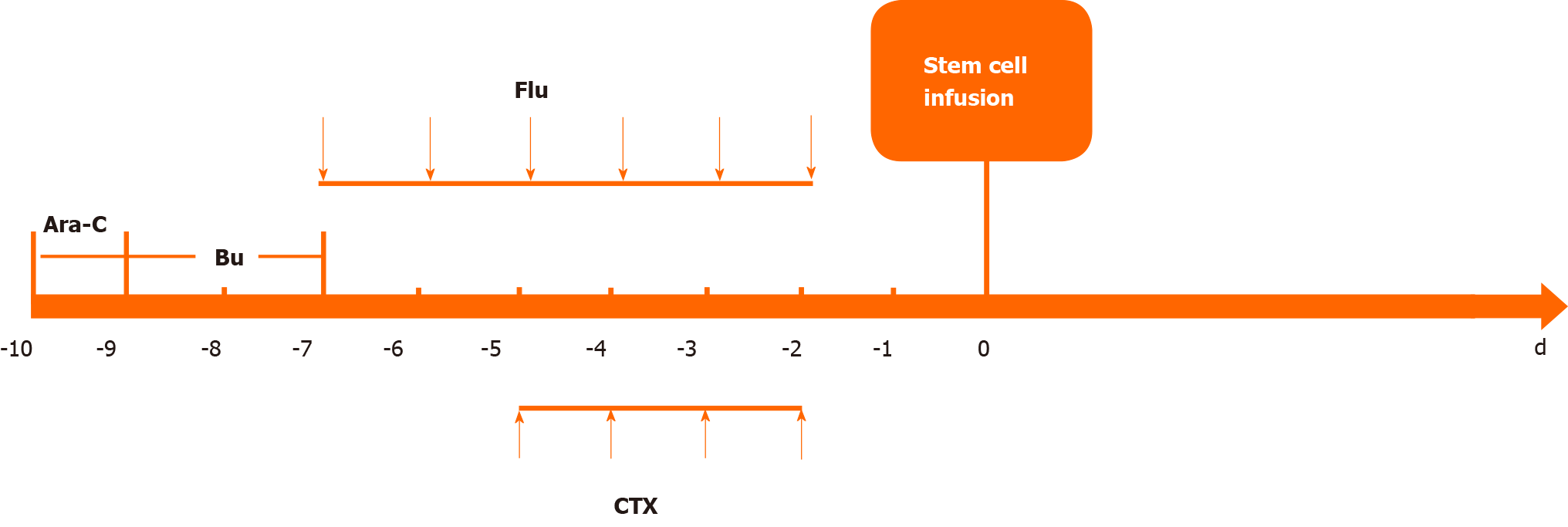

After the diagnosis of AML (M2), we administered induction chemotherapy to the patient using the daunorubicin, cytarabine and homoharringtonine regimen. Blast cells were not observed in cerebrospinal fluid after cytological examination. Bone marrow aspiration was performed 14 d after the first 7-d induction therapy and suggested no response with 79% blast cells. Treatment with idarubicin, cytarabine and homoharringtonine was initiated immediately as the second induction therapy. The patient still had a poor response with 10% blast cells and hypoplasia on day 15 and 60% blast cells in the bone marrow on day 21 after the second induction cycle. Then the patient was treated with the CLAG regimen combined with mitoxantrone as salvage therapy. The CLAG-M protocol herein consisted of cladribine (5 mg/m2 intravenously in 2 h from day 1 to day 5), granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (300 µg/m2 hypodermic injection from day 0 to day 5), cytarabine (1 g/m2 in 3 h intravenously infusions) and mitoxantrone (10 mg/m2 intravenously daily for 3 d) (Figure 2). Routine bone marrow aspiration was done on day 15 after completion of the CLAG-M regimen. The patient achieved complete remission (CR) with 2% blast cells in the bone marrow but had severe bone marrow suppression after salvage therapy, and the duration of neutropenia was 14 d. The patient experienced febrile neutropenia, pneumonia and acroposthitis. The infection complications were controlled using antibiotics. He received six units of packed red cells and five units of platelets due to bone marrow suppression. Other nonhaematological toxicities associated with CLAG-M were mild. Given that matched sibling donors were not available, the patient underwent haematopoietic stem cell transplantation after salvage therapy using unrelated umbilical cord blood (10/10 matched). The myeloablative conditioning protocol included cytarabine, busulfan, fludarabine and cyclophosphamide (Figure 3). The prophylactic treatment for graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) consisted of mycophenolate mofetil and cyclosporine A. Transplantation-related toxicity was evidenced by perianal soft tissue infection and febrile neutropenia. Engraftment syndrome and grade II acute skin GVHD occurred but were alleviated by the use of systemic steroids.

Bone marrow assessment 30 d post-HSCT found morphological remission to be complete and both WT1 and KRAS mutation negative. To date, over 60 d after transplantation, no other adverse effects have been detected, and complete graft chimerism has been achieved. Post-HSCT immunosuppressive treatment is tapering according to the control of GVHD. The status of primary disease and transplantation-related complications are under close monitoring.

R/R AML remains the leading cause of failed treatment in children with AML. Some new chemotherapy regimens promise to be effective in this population. We chose the CLAG-M protocol to treat this patient with primary refractory paediatric AML for several reasons. First, the synergistic antileukaemic effect between cytarabine and cladribine was detected in vivo and in vitro[4]. 2-CdA augments the cytotoxic effect of cytarabine by increasing the accumulation of cytarabine triphosphate, the active form of Ara-C. Second, given the fundamental premises, a phase II study from the PALG reported significant efficacy of the CLAG-M protocol in adult R/R AML[5]. Third, the combination of cladribine and cytarabine was found to be effective as salvage therapy for refractory multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis[6], which is also classified as a “myeloproliferative neoplasm”[7].

In the past, the combination of cladribine and anthracycline was the backbone of treatment for AML. The cladribine-based regimen is one of the aggressive treatment options for adult R/R AML in recent recommendations from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network[8]. One of the earliest studies of cladribine was performed by Santana et al[2] in 1991. After being treated with single-agent 2-CdA, 47% of 18 paediatric patients with R/R AML achieved CR[9].

Clinical trials have expanded to different cladribine-based combination regimens. Data from studies of paediatric AML supported cladribine-based regimens showed significant antileukaemic activity in this population. Although Rubnitz et al[10] reported a disappointing response in eight patients with R/R AML who were pretreated with 2-CdA and Ara-C, the results of the St. Jude AML97 trial indicated that the combination of cladribine and cytarabine as window therapy before standard induction therapy was effective for newly diagnosed paediatric AML[11]. A report from St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital showed that dose-escalating 2-CdA combined with topotecan yielded a CR rate of 35% in 26 children with R/R AML[12]. A phase II study of 2-CdA plus idarubicin as salvage therapy for paediatric R/R AML showed an overall response rate of 51%[13].

Several researchers carried out similar trials in adult AML patients. PALG first reported the use of the CLAG protocol for adults with R/R AML in 2003[14]. A later study by PALG reported that CLAG-M led to a CR rate of 58% in 114 adult R/R AML patients[3]. A retrospective study by Price et al[15] concluded that the CLAG protocol achieved a higher CR rate in first-relapsed adult AML patients compared with the mitoxantrone, etoposide and cytarabine protocol (36.8% vs 25.9%). Seligson et al[16] also found that the addition of cladribine to traditional AML induction therapy was beneficial to adult AML patients. Another study suggested that patients with de novo AML who had achieved CR at first induction therapy had a better survival rate when treated with the cladribine-based protocol than a fludarabine-based protocol[17].

CLAG was equally effective to the FLAG protocol in R/R AML patients, while subgroup analysis disclosed that CLAG had a higher CR in those with second or higher salvage therapy[18]. These data indicate that the cladribine-based protocol may raise the rate of CR in R/R AML patients, enabling these patients to undergo HSCT. A summary of key published data for 2-CdA-based treatment in paediatric and adult AML can be found in Table 1.

| Ref. | Patient number | Patient characteristic | Age | Regimen | Overall response rate, % | Number of patients who received subsequent HSCT | OS | Early death, n |

| Santana et al[2], 1991 | 31 | Paediatric, R/R ALL and AML | 10 (1-21) yr | 2- CdA | 11% (25% in AML) | NR | NR | 3 |

| Santana et al[9], 1992 | 24 | Paediatric, R/R ALL and AML | 11 (3-23) yr | 2- CdA | CR: 47% (8/17), PR: 12% (2/17) | 7 | NR | 0 |

| Rubnitz et al[10], 2004 | 8 | Paediatric, R/R AML | 5.0 (0.6-16.0) yr | 2-CdA + Ara-C | 0 | 0 | NR | NR |

| Rubnitz et al[11], 2009 | 102 | Paediatric, ND AML | 9.03 (0.05-21.00) yr | 2-CdA + Ara-C, followed by DAE | CR 50% | 32 (Allo-HSCT)9 (Auto-HSCT) | 5-yr OS: 50.0% ± 5.5% | 15 |

| Inaba et al[12], 2010 | 26 | Paediatric, R/R AML | 10.0 (1.0-19.0) yr | 2-CdA + Topotecan | CR 34.6%PR 30.4% | 8 | Long-term survival: 19.2% | 4 |

| Chaleff et al[13], 2012 | 104 | Paediatric, R/R | 75 (33–95) mo | 2- CdA + IDA | 51% | NR | 26% at 2 yr | 5 |

| Wrzesien-Kus et al[14], 2003 | 58 | Adult, R/R | 45 (18–67) yr | CLAG | 50% | 2 (Allo-HSCT)4 (Auto-HSCT) | 42% at 1 yr | 10 |

| Wierzbowska et al[3], 2008 | 118 | Adult, R/R | 45 (20–66) yr | CLAG-M | 58% | 20 (Allo-HSCT)6 (Auto-HSCT) | 14% at 4 yr | 7 |

| Price et al[15], 2010 | 162 | Adult, R/R | CLAG: 55.1 (23.0–83.0) yr, MEC: 55.0 (21.0–90.0) yr | CLAG/MEC | CR: 37.9% (CLAG), CR: 23.8% (MEC) | NR | Median survival: 11.0 mo (CLAG), 4.5 mo (MEC) | 9.4% (CLAG), 10.9% (MEC) |

| Park et al[17], 2016 | 120 | Adult, R/R | 56.6 (19.0–83.0) yr | CLAG/CLAG-M/FLAG/FLAGI/mFLAI | CR: 62.7% (CLAG/CLAGM), CR: 61.4% (FLAG/FLAGI/mFLAI) | 33 | 34.0% at 1 yr, 21.4% at 5 yr | NR |

| Bao et al[18], 2017 | 103 | Adult, R/R | CLAG: 51.0 ± 17.7 yr, FLAG: 48.8 ± 17.5 yrs | CLAG/FLAG | CR: 61.7% (CLAG), CR: 48.7% (FLAG) | 11 (CLAG), 10 (FLAG) | CLAG: 45.5% at 1 yr, 35.3% at 3 yr, FLAG: 35.4% at 1 yr, 26.8% at 3 yr | NR |

| Seligson et al[16], 2018 | 37 | Adult, ND | 7 + 3 IA: 61 (27-79) yr, 7 + 3 + 5 IAC: 58 (36-71) yr | 7 + 3 IA/ 7 + 3 + 5 IAC | CR: 42% (7 + 3 IA), CR: 34% (7 + 3 + 5 IAC) | NR | NR | NR |

| Mirza et al[19], 2017 | 38 | Adult, R/R | 62 (26-79) yr | CLAG + Imatinib | CR: 37%, PR: 11% | 8 | 11.1 mo (95%CI: 4.8-13.4 mo) | 2 |

Optimization of the salvage regimen is important to improve prognosis in paediatric R/R AML. A bridge to HSCT is the primary goal of salvage therapy. The efficacy of CLAG-M in paediatric R/R AML has not been reported before. Our patient showed a good response to the CLAG-M protocol and achieved CR after reinduction therapy. Studies on the combination of CLAG with other agents are ongoing. For instance, a later study suggested that the CLAG protocol combined with imatinib also had impressive activity in patients with high-risk AML[19].

Genetic analysis of the patient revealed heterozygous mutations both in the WT1 gene and the KRAS gene. About 76% of paediatric patients with AML had at least one gene mutation. WT1 and KRAS gene mutations were found in over 10% of paediatric AML patients. WT1 was associated with a poorer 3-yr overall survival and/or event-free survival[20]. Results from another study also found WT1 mutations were related to an inferior outcome in patients with cytogenetically normal AML, excluding patients with FLT3-ITD and those less than 3-years-old[21]. KRAS mutation was found to be a distinct adverse prognostic factor in paediatric patients with mixed lineage leukaemia-rearranged AML, regardless of risk subgroup[22]. However, whether the presence of the co-occurrence of WT1 and KRAS mutations could increase the response rate to cladribine-based salvage therapy still remains unclear.

Chemotherapy alone is unlikely to be curative in patients with primary refractory or relapsed AML due to drug resistance. HSCT is often used after achievement of remission. Our patient received unrelated umbilical cord blood transplantation after complete remission. His bone marrow kept up a morphological CR after umbilical cord blood transplantation. Additionally, genetic abnormalities also disappeared. Haematologic toxicity was the most prominent toxicity in the cladribine-based regimen. Although cladribine has limited acute toxicities, there are no increased haematopoietic toxicities reported in paediatric patients or in patients aged over 60 years[11,13,23]. Our patient also experienced approximately 2 wk of neutropenia and infections due to myelosuppression, but the infections were well controlled using antibacterial and antifungal agents. Other adverse events of the CLAG-M protocol were mild and tolerable. We would suggest using prophylactic antifungal agents during grade 3 to 4 neutropenia. This is the first case report of using the CLAG-M protocol in childhood R/R AML. Our patient successfully achieved complete remission before HSCT.

In conclusion, the CLAG-M protocol might be an effective and well-tolerated salvage regimen in R/R AML in childhood. Further studies on a large group of paediatric patients are warranted to investigate the efficacy of the CLAG-M protocol as salvage treatment or as a bridge to HSCT. Moreover, the possibility of a cladribine-based protocol being used as first line therapy in high-risk paediatric patients also needs further investigation. A study on the effectiveness and safety of the CLAG combined with anthracyclines in paediatric R/R AML has been launched in our hospital.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Biondi A, Pérez-Campo FM S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Zwaan CM, Kolb EA, Reinhardt D, Abrahamsson J, Adachi S, Aplenc R, De Bont ES, De Moerloose B, Dworzak M, Gibson BE, Hasle H, Leverger G, Locatelli F, Ragu C, Ribeiro RC, Rizzari C, Rubnitz JE, Smith OP, Sung L, Tomizawa D, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Creutzig U, Kaspers GJ. Collaborative Efforts Driving Progress in Pediatric Acute Myeloid Leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2949-2962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 273] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Santana VM, Mirro J Jr, Harwood FC, Cherrie J, Schell M, Kalwinsky D, Blakley RL. A phase I clinical trial of 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine in pediatric patients with acute leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:416-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wierzbowska A, Robak T, Pluta A, Wawrzyniak E, Cebula B, Hołowiecki J, Kyrcz-Krzemień S, Grosicki S, Giebel S, Skotnicki AB, Piatkowska-Jakubas B, Kuliczkowski K, Kiełbiński M, Zawilska K, Kłoczko J, Wrzesień-Kuś A; Polish Adult Leukemia Group. Cladribine combined with high doses of arabinoside cytosine, mitoxantrone, and G-CSF (CLAG-M) is a highly effective salvage regimen in patients with refractory and relapsed acute myeloid leukemia of the poor risk: a final report of the Polish Adult Leukemia Group. Eur J Haematol. 2008;80:115-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gandhi V, Estey E, Keating MJ, Chucrallah A, Plunkett W. Chlorodeoxyadenosine and arabinosylcytosine in patients with acute myelogenous leukemia: pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, and molecular interactions. Blood. 1996;87:256-264. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Wrzesień-Kuś A, Robak T, Wierzbowska A, Lech-Marańda E, Pluta A, Wawrzyniak E, Krawczyńska A, Kuliczkowski K, Mazur G, Kiebiński M, Dmoszyńska A, Wach M, Hellmann A, Baran W, Hołowiecki J, Kyrcz-Krzemień S, Grosicki S; Polish Adult Leukemia Group. A multicenter, open, noncomparative, phase II study of the combination of cladribine (2-chlorodeoxyadenosine), cytarabine, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and mitoxantrone as induction therapy in refractory acute myeloid leukemia: a report of the Polish Adult Leukemia Group. Ann Hematol. 2005;84:557-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Donadieu J, Bernard F, van Noesel M, Barkaoui M, Bardet O, Mura R, Arico M, Piguet C, Gandemer V, Armari Alla C, Clausen N, Jeziorski E, Lambilliote A, Weitzman S, Henter JI, Van Den Bos C; Salvage Group of the Histiocyte Society. Cladribine and cytarabine in refractory multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis: results of an international phase 2 study. Blood. 2015;126:1415-1423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Allen CE, Ladisch S, McClain KL. How I treat Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2015;126:26-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Acute Myeloid Leukemia [Version 2.2020]. [cited 13 Aug 2019] In: National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/aml_blocks.pdf. |

| 9. | Santana VM, Mirro J Jr, Kearns C, Schell MJ, Crom W, Blakley RL. 2-Chlorodeoxyadenosine produces a high rate of complete hematologic remission in relapsed acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:364-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rubnitz JE, Razzouk BI, Srivastava DK, Pui CH, Ribeiro RC, Santana VM. Phase II trial of cladribine and cytarabine in relapsed or refractory myeloid malignancies. Leuk Res. 2004;28: 349-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rubnitz JE, Crews KR, Pounds S, Yang S, Campana D, Gandhi VV, Raimondi SC, Downing JR, Razzouk BI, Pui CH, Ribeiro RC. Combination of cladribine and cytarabine is effective for childhood acute myeloid leukemia: results of the St Jude AML97 trial. Leukemia. 2009;23:1410-1416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Inaba H, Stewart CF, Crews KR, Yang S, Pounds S, Pui CH, Rubnitz JE, Razzouk BI, Ribeiro RC. Combination of cladribine plus topotecan for recurrent or refractory pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer. 2010;116:98-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chaleff S, Hurwitz CA, Chang M, Dahl G, Alonzo TA, Weinstein H. Phase II study of 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine plus idarubicin for children with acute myeloid leukaemia in first relapse: a paediatric oncology group study. Br J Haematol. 2012;156:649-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wrzesień-Kuś A, Robak T, Lech-Marańda E, Wierzbowska A, Dmoszyńska A, Kowal M, Hołowiecki J, Kyrcz-Krzemień S, Grosicki S, Maj S, Hellmann A, Skotnicki A, Jedrzejczak W, Kuliczkowski K; Polish Adult Leukemia Group. A multicenter, open, non-comparative, phase II study of the combination of cladribine (2-chlorodeoxyadenosine), cytarabine, and G-CSF as induction therapy in refractory acute myeloid leukemia - a report of the Polish Adult Leukemia Group (PALG). Eur J Haematol. 2003;71:155-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Price SL, Lancet JE, George TJ, Wetzstein GA, List AF, Ho VQ, Fernandez HF, Pinilla-Ibarz J, Kharfan-Dabaja MA, Komrokji RS. Salvage chemotherapy regimens for acute myeloid leukemia: Is one better? Leuk Res. 2011;35:301-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Seligson ND, Hobbs ALV, Leonard JM, Mills EL, Evans AG, Goorha S. Evaluating the Impact of the Addition of Cladribine to Standard Acute Myeloid Leukemia Induction Therapy. Ann Pharmacother. 2018;52:439-445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Park H, Youk J, Kim I, Yoon SS, Park S, Lee JO, Bang SM, Koh Y. Comparison of cladribine- and fludarabine-based induction chemotherapy in relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukaemia. Ann Hematol. 2016;95:1777-1786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bao Y, Zhao J, Li ZZ. Comparison of clinical remission and survival between CLAG and FLAG induction chemotherapy in patients with refractory or relapsed acute myeloid leukemia: a prospective cohort study. Clin Transl Oncol. 2018;20:870-880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Mirza AS, Lancet JE, Sweet K, Padron E, Pinilla-Ibarz J, Nardelli L, Cubitt C, List AF, Komrokji RS. A Phase II Study of CLAG Regimen Combined With Imatinib Mesylate for Relapsed or Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2017;17:902-907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Marceau-Renaut A, Duployez N, Ducourneau B, Labopin M, Petit A, Rousseau A, Geffroy S, Bucci M, Cuccuini W, Fenneteau O, Ruminy P, Nelken B, Ducassou S, Gandemer V, Leblanc T, Michel G, Bertrand Y, Baruchel A, Leverger G, Preudhomme C, Lapillonne H. Molecular Profiling Defines Distinct Prognostic Subgroups in Childhood AML: A Report From the French ELAM02 Study Group. Hemasphere. 2018;2:e31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sano H, Shimada A, Tabuchi K, Taki T, Murata C, Park MJ, Ohki K, Sotomatsu M, Adachi S, Tawa A, Kobayashi R, Horibe K, Tsuchida M, Hanada R, Tsukimoto I, Hayashi Y. WT1 mutation in pediatric patients with acute myeloid leukemia: a report from the Japanese Childhood AML Cooperative Study Group. Int J Hematol. 2013;98:437-445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Matsuo H, Yoshida K, Nakatani K, Harata Y, Higashitani M, Ito Y, Kamikubo Y, Shiozawa Y, Shiraishi Y, Chiba K, Tanaka H, Okada A, Nannya Y, Takeda J, Ueno H, Kiyokawa N, Tomizawa D, Taga T, Tawa A, Miyano S, Meggendorfer M, Haferlach C, Ogawa S, Adachi S. Fusion partner-specific mutation profiles and KRAS mutations as adverse prognostic factors in MLL-rearranged AML. Blood Adv. 2020;4:4623-4631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Juliusson G, Höglund M, Karlsson K, Löfgren C, Möllgård L, Paul C, Tidefelt U, Björkholm M; Leukemia Group of Middle Sweden. Increased remissions from one course for intermediate-dose cytosine arabinoside and idarubicin in elderly acute myeloid leukaemia when combined with cladribine. A randomized population-based phase II study. Br J Haematol. 2003;123:810-818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |