Published online Nov 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i22.5564

Peer-review started: August 12, 2020

First decision: August 22, 2020

Revised: August 25, 2020

Accepted: September 26, 2020

Article in press: September 26, 2020

Published online: November 26, 2020

Processing time: 105 Days and 5.6 Hours

Locally advanced pancreatic cancer (LAPC) is a common malignant digestive system tumor that ranks as the fourth leading cause of cancer-related death in the world. The prognosis of LAPC is poor even after standard treatment. Irreversible electroporation (IRE) is a novel ablative strategy for LAPC. Several studies have confirmed the safety of IRE. To date, no prospective studies have been performed to investigate the therapeutic efficacy of conventional gemcitabine (GEM) plus concurrent IRE.

To compare the therapeutic efficacy between conventional GEM plus concurrent IRE and GEM alone for LAPC.

From February 2016 to September 2017, a total of 68 LAPC patients were treated with GEM plus concurrent IRE n = 33) or GEM alone n = 35). Overall survival (OS), progression free survival (PFS), and procedure-related complications were compared between the two groups. Multivariate analyses were performed to identify any prognostic factors.

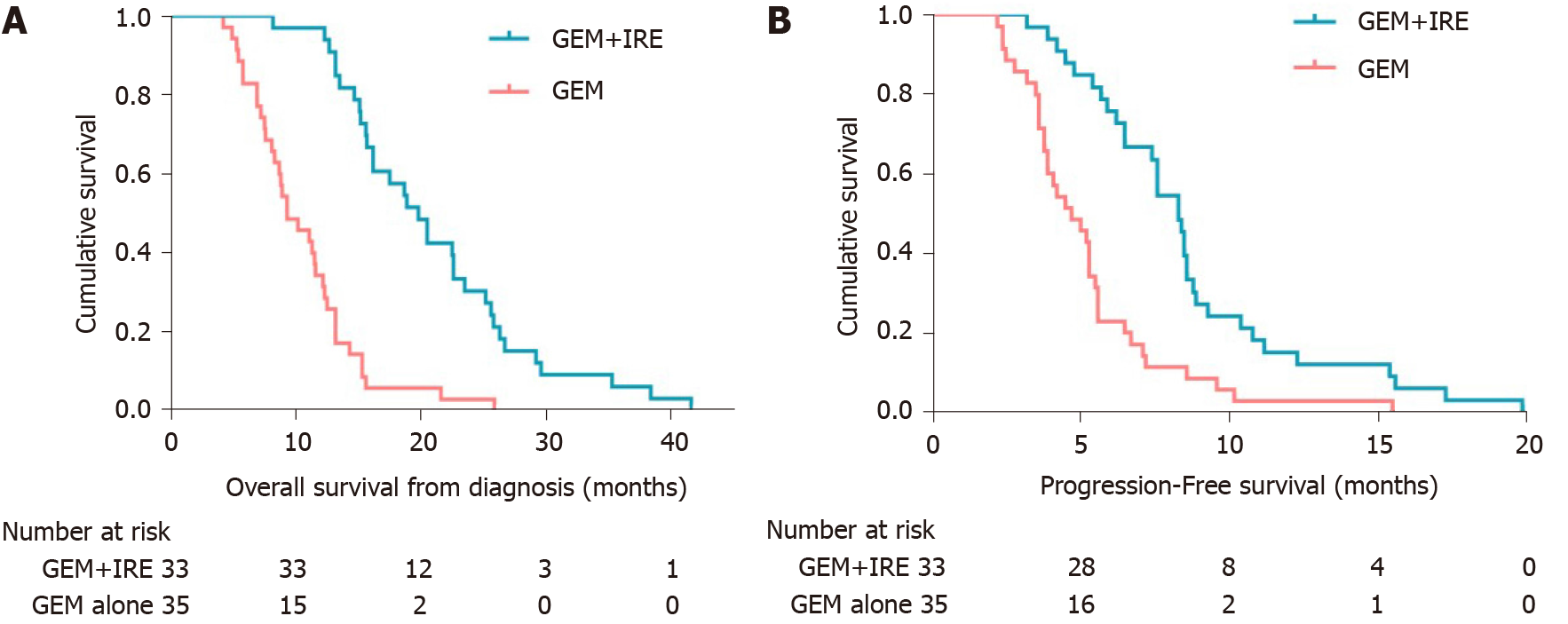

There were no treatment-related deaths. The technical success rate of IRE ablation was 100%. The GEM + IRE group had a significantly longer OS from the time of diagnosis of LAPC (19.8 mo vs 9.3 mo, P < 0.0001) than the GEM alone group. The GEM + IRE group had a significantly longer PFS (8.3 mo vs 4.7 mo, P < 0.0001) than the GEM alone group. Tumor volume less than 37 cm3 and GEM plus concurrent IRE were identified as significant favorable factors for both the OS and PFS.

Gemcitabine plus concurrent IRE is an effective treatment for patients with LAPC.

Core Tip: Locally advanced pancreatic cancer (LAPC) is a common malignant digestive system tumor with poor prognosis. Gemcitabine (GEM) is currently used as a first-line chemotherapy for treatment of LAPC; however, the overall outcome was poor. Irreversible electroporation (IRE) is a novel, non-thermal ablation technology that uses high voltage electrical pulses to induce pore formation, resulting in cell apoptosis. We found that GEM plus concurrent IRE resulted in significantly prolonging overall survival compared with chemotherapy alone. Therefore, GEM plus concurrent IRE has a synergistic effect on the clinical treatment of LAPC.

- Citation: Ma YY, Leng Y, Xing YL, Li HM, Chen JB, Niu LZ. Gemcitabine plus concurrent irreversible electroporation vs gemcitabine alone for locally advanced pancreatic cancer. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(22): 5564-5575

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i22/5564.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i22.5564

Locally advanced pancreatic cancer (LAPC) is a common malignant digestive system tumor that ranks as the fourth leading cause of cancer-related death in the world. The 5-year survival rate remains less than 8%[1]. The main reason for the dismal survival rate is a lack of early specific symptoms and most patients have progressed to late-stage disease when diagnosed[2]. Surgical resection has been considered the standard treatment for patients with pancreatic cancer. However, fewer than 20% of patients have surgical opportunities[3]. Furthermore, since 1997, gemcitabine-based regimens have been the first-line of treatment for patients with LAPC, however, the prognosis remains poor[4-6].

Irreversible electroporation (IRE) is an emerging physical ablation technology that uses transient high voltage short pulses to destroy the integrity of the phospholipid bilayer, and causes irreversible perforation of the cell membrane. The membrane structure and the internal environmental balance of the cell are permanently destroyed, resulting in cell apoptosis[7,8]. Compared with thermal ablation (microwave and radiofrequency), IRE does not cause heat-related damage to important blood vessels, bile ducts, and gastrointestinal structures since IRE ablation does not change the structure of the extracellular matrix[9,10]. Although previous studies have investigated the role of IRE combined with conventional treatment, most studies were retrospective and had limited sample sizes, and results with from these studies are contradictory and inconclusive[11,12].

To date, there has been a lack of prospective data to verify the therapeutic outcome of gemcitabine (GEM) plus concurrent IRE. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine whether GEM plus concurrent IRE improves the therapeutic efficacy for patients with LAPC.

This prospective study (NCT02981719) was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Affiliated Fuda Cancer Hospital, Jinan University. All patients provided a written informed consent form, which was signed by the patient or their families prior to treatment.

Between February 2016 and September 2017, patients who were scheduled to undergo IRE for pancreatic cancer were prospectively enrolled in this study. Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria listed in Table 1, a total of 68 LAPC patients were enrolled in this study. LAPC was defined in accordance with the seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system for pancreatic cancer[13]. According to a computer-generated randomization program, the patients were divided into two groups: (1) GEM + IRE group, including 33 patients treated with gemcitabine plus concurrent irreversible electroporation; and (2) GEM alone group, including 35 patients treated with gemcitabine alone. The clinical characteristics of the 68 patients are summarized in Table 2.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Radiologic confirmation of locally advanced pancreatic cancer | Resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma |

| Histological or cytological confirmation of pancreatic adenocarcinoma | Chemotherapy or radiotherapy prior to the procedure |

| Tumor diameter ≤ 5 cm | Allergy to contrast media |

| Age ≥ 18 yr | History of epilepsy |

| Adequate bone marrow, liver, renal, and coagulation function: Hemoglobin level ≥ 115 g/L; platelet count ≥ 100 × 109/L; neutrophil count ≥ 2 × 109/L; white blood cell count ≥ 4 × 109/L | History of cardiac disease: Congestive heart failure > NYHA classification 2; cardiac arrhythmias requiring anti-arrhythmic therapy or pacemaker |

| PS 0-2 | Uncontrolled hypertension |

| Written informed consent | Any implanted metal stent/device within the area of ablation that cannot be removed |

| Characteristic | GEM + IRE group (n = 33) | GEM group (n = 35) | P value |

| Age, yr | |||

| Median | 63 | 65 | |

| Range | 45-86 | 39-81 | |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 18 (54.5) | 19 (54.3) | 0.983 |

| Male | 15 (45.5) | 16 (45.7) | |

| Pathology | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 26 | 23 | |

| Lesion size (cm) | 4.1 (3.0-5.0) | 3.9 (3.0-5.0) | |

| Tumor location | |||

| Head and neck | 23 (23.3) | 21 (26.7) | 0.686 |

| Body and tail | 5 (40.0) | 6 (50.0) | |

| Previous surgical therapy | 0.479 | ||

| Gastrojejunostomy | 3 (9.1) | 4 (11.4) | |

| Hepaticojejunostomy | 1 (3.0) | 2 (5.7) | |

| Double bypass | 2 (6.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Plastic retrievable endoprosthesis | 1 (3.0) | 1 (2.9) | |

| Performance status | 0.757 | ||

| 0 | 12 (36.3) | 14 (40.0) | |

| 1 | 21 (63.7) | 21 (60.0) | |

| Accepted treatment | 0.681 | ||

| Biliary bypass and gastrojejunostomy | 2 (6.1) | 1 (2.9) | |

| Cholecystectomy | 1 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Gastroenterostomy | 2 (6.1) | 2 (5.7) | |

| Herb therapy | 2 (6.1) | 3 (8.6) | |

| Immunotherapy | 1 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) |

All procedures were performed by two interventional radiologists with 10 to 15 years of experience in tumor ablation at the beginning of this study. A computed tomography (CT) plain scan and 3D reconstruction of the vascular anatomy tumor were performed to assess the tumor size, number, location, and relation of the tumor to vascular structures before the procedure, and plan the electrode probe implantation path in advance to avoid damaging the blood vessels.

Before the IRE ablation started, patients received 1000 mg/m2 gemcitabine hydrochloride [Qilu pharmaceutical (Hainan) Co., Ltd. Haikou, China] intravenously (over approximately 30 min). During the IRE process, all patients were placed in the supine position under general anesthesia[14]. The patients were then given muscle relaxation drugs. A CT scanner (Somatom Definition AS, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) and ultrasound system (IU22, Philips Healthcare, Bothell, WA, United States) were used to confirm the tumor morphology and surrounding relationships combined with preoperative planning for probe placement. Depending on the size and location of the tumor, two to five probes were used. The exposed length of the probes tip was approximately 15-20 mm. All probes were placed as parallel as possible to ensure uniform electric field distribution. A setting of 1500 V/cm was used as the initial setting, and planned to transmit 90 pulses at a pulse length of 70 to 90 ms. To ensure complete coverage of the target area, the target current was in the range of 20-50 A, and in order to avoid over- or under-current, the patient's vital signs were closely observed 24 h after the operation and symptomatic treatment was administered. Contrast-enhanced CT was performed immediately after ablation to confirm that the tumor had completely covered the area and to detect any early complications.

Chemotherapy was initiated 2-4 wk after IRE ablation. GEM was administered at 1000 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15. The time for each intravenous infusion was not less than 30 min. Every 4 wk was considered to be a course of treatment. Each patient received six courses of chemotherapy. All doses of GEM were calculated according to the body surface area, which was based on height and weight. When tumor has progressed, second-line chemotherapy was administered.

The chemotherapy regimen in the GEM group is the same as that in the GEM + IRE group.

In both groups, follow-up procedures were carried out every 2-3 mo during the first year, and every 3-6 mo thereafter. All follow-up scan results were independently interpreted by two radiologists. Adverse events were recorded and graded.

An independent sample t-test was used to compare the independent-samples and data between groups. The relationship between different variables was assessed using a chi-square test. Survival curves for the overall survival (OS) and progression free survival (PFS) were estimated via the Kaplan-Meier method and analyzed using a log-rank test. The univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to identify significant variables using the Cox regression model to study the effects of different variables on survival. The associated corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were also subsequently calculated. A P value less than 0.05 using a two-tailed t-test was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were carried out using commercially available software (SPSS version 21.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States).

Between February 2016 and September 2017, a total of 68 LAPC patients were treated with one of the two therapies. Of these, 33 patients received GEM plus concurrent IRE and 35 received GEM alone. The baseline characteristics of the clinical and pathological variables are summarized in Table 2. The median age for patients in the GEM + IRE group and GEM group was 63 years (range: 45-86 years) and 65 years (range: 39-81 years), respectively. The largest median tumor diameter was 4.1 cm (range: 3.5-4.8 cm) and 3.9 (range: 3.2-4.6 cm) in the GEM + IRE and GEM alone group, respectively. The technical success rate of IRE ablation was 100%. Figure 1 provides an example of the typical imaging characteristics of the pancreatic tumor before, during, and 6 mo after IRE. None of the patients were down-staged to resection following treatment. No patients were lost to follow-up.

The median OS was 19.8 and 9.3 mo from the time of diagnosis in the GEM + IRE group and GEM alone group, respectively (P < 0.0001) (Figure 2A). A total of 44 patients experienced tumor progression during this study, including 15 (45.4%) patients in the GEM + IRE group and 29 (82.8%) in the GEM alone group (P < 0.001). The median PFS for patients in the GEM + IRE group and GEM alone group was 8.3 and 4.7 mo, respectively (P < 0.0001) (Figure 2B). These results indicate that the GEM + IRE group and GEM alone group displayed similar clinical and laboratory features. Tumor progression occurred more rapidly in the GEM alone group compared to the GEM + IRE group.

The results of the univariable and multivariable Cox regression analyses for the OS and PFS are presented in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. Variables such as age, gender, tumor size, tumor volume, liver function, and CA19-9 were included in the Cox regression analysis. A univariate analysis for the OS showed that gemcitabine treatment (with vs without IRE; hazard ratio (HR) = 2.321; 95%CI: 0.178-0.952; P = 0.045), carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) level lower than 50% at 3 mo after IRE treatment (HR = 2.659; 95%CI: 1.096-6.532; P = 0.032), and tumor volume (≤ 37 cm3vs > 37 cm3; HR = 2.386; 95%CI: 1.312-4.415; P = 0.008) were associated with OS. Furthermore, independent prognostic factors identified by the multivariate analysis included GEM plus concurrent IRE treatment (HR = 0.422; 95%CI: 0.157-0.958; P = 0.047) and tumor volume less than 37 cm3 (HR = 2.913; 95%CI: 1.181-6.381; P = 0.023) (Table 3).

| Characteristic | GEM + IRE group (n = 33) | GEM group (n = 35) | |||||

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | ||

| Age (yr) | ≤ 60/> 60 | 1.632 | 0.763-3.325 | 0.121 | |||

| Gender | Female/male | 2.321 | 1.202-4.047 | 0.215 | |||

| Tumor site | Head/body/tail | 0.952 | 0.676-1.524 | 0.832 | |||

| Tumor volume (cm3) | ≤ 37/> 37 | 2.386 | 1.312-4.415 | 0.008 | 2.913 | 1.181-6.381 | 0.023 |

| WBC (× 109) | ≤ 10/> 10 | 1.128 | 0.343-2.872 | 0.988 | |||

| HGB (g/L) | ≤ 120/> 120 | 0.586 | 0.254-1.693 | 0.383 | |||

| PLT (× 109) | ≤ 300/> 300 | 1.218 | 0.526-2.867 | 0.672 | |||

| ALT (U/L) | ≤ 40/> 40 | 0.778 | 0.368-1.686 | 0.514 | |||

| AST (U/L) | ≤ 40/> 40 | 0.427 | 0.275-1.406 | 0.209 | |||

| ALP (U/L) | ≤ 100/> 100 | 0.895 | 0.506-1.824 | 0.793 | |||

| CEA (ng/mL) | ≤ 5/> 5 | 1.381 | 1.027-2.741 | 0.474 | |||

| CA19-9 level | ≤ 35/> 35 | 1.350 | 0.618-3.572 | 0.245 | |||

| CA19-9 decrease 3 mo after treatment | ≤ 50%/>50% | 2.659 | 1.096-6.532 | 0.032 | 3.084 | 1.304-7.854 | 0.011 |

| GEM | With/without IRE | 0.389 | 0.178-0.952 | 0.045 | 0.422 | 0.157-0.958 | 0.047 |

| Characteristic | GEM + IRE group (n = 33) | GEM group (n = 35) | |||||

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | ||

| Age (yr) | ≤ 60/> 60 | 1.167 | 0.669-2.203 | 0.554 | |||

| Gender | Female/male | 1.602 | 0.942-2.802 | 0.097 | |||

| Tumor size (cm) | ≤ 4/> 4 | 0.787 | 0.489-1.280 | 0.334 | |||

| Tumor site | Head/body/tail | 0.942 | 0.623-1.410 | 0.750 | |||

| Tumor volume (cm3) | ≤ 37/> 37 | 2.386 | 1.298-4.406 | 0.012 | 2.856 | 1.180-6.420 | 0.025 |

| WBC (× 109) | ≤ 10/> 10 | 1.149 | 0.468-2.575 | 0.697 | |||

| HGB (g/L) | ≤ 120/> 120 | 0.587 | 0.298-1.513 | 0.285 | |||

| PLT (× 109) | ≤ 300/> 300 | 0.653 | 0.274-1.752 | 0.342 | |||

| ALT (U/L) | ≤ 40/> 40 | 0.542 | 0.433-1.533 | 0.341 | |||

| AST (U/L) | ≤ 40/> 40 | 0.636 | 0.347-1.521 | 0.304 | |||

| ALP (U/L) | ≤ 100/> 100 | 0.726 | 0.521-1.367 | 0.572 | |||

| CEA (ng/mL) | ≤ 5/> 5 | 1.322 | 0.715-2.602 | 0.162 | |||

| CA19-9 (U/ml) | ≤ 35/> 35 | 2.056 | 1.009-3.019 | 0.052 | |||

| CA19-9 decrease 3 mo after IRE | ≤ 50%/> 50% | 2.258 | 0.895-6.428 | 0.032 | |||

| GEM | With/without IRE | 0.557 | 0.308-1.210 | 0.046 | 0.582 | 0.322-1.050 | 0.042 |

Univariate and multivariate analyses were also used to evaluate PFS in Table 4. It was shown that GEM treatment (with vs without IRE; HR = 0.557; 95%CI: 0.308-1.210; P = 0.046), tumor volume (≤ 37 cm3vs > 37 cm3; HR = 2.386; 95%CI: 1.298-4.406; P = 0.012), and CA 19-9 decrease 3 mo after IRE (≤ 50% vs > 50%; HR = 2.258; 95%CI: 0.895-6.428; P =0.032) were associated with PFS. Moreover, GEM plus concurrent IRE treatment (HR = 0.582; 95%CI: 0.322-1.050; P = 0.042) and tumor volume less than 37 cm3 (HR = 2.856; 95%CI: 1.180-6.420; P = 0.025) were considered significant predictors of PFS (Table 4).

Overall, no patients died within 90 d after IRE treatment. Table 5 summarizes the adverse events in the two groups. The minor adverse reactions in the two groups included nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, loss of appetite and/or reduced intake, mild ascites, thrombocytopenia, hemoglobin reduction, leukocyte reduction, and hypoalbuminemia. The most frequently reported toxicities were hypoalbuminemia and hemoglobin reduction for patients in the GEM + IRE group. The major adverse events included pancreatitis (n = 2; 6.0%) and bleeding from duodenal ulcers (n = 1; 3.0%) 18 d after IRE in the GEM + IRE group, which was treated using transcatheter arterial embolization to occlude the vessel proximal to the bleeding site. All complications were resolved within about 2 wk. The difference in the incidence of adverse reactions between the two groups was not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

| Adverse event | GEM + IRE group (n = 33) | GEM group (n = 35) | ||||

| Grade | I/II | III | IV | I/II | III | IV |

| Toxicity | ||||||

| Hypoalbuminemia | 5 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Lymphopenia | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Hemoglobin reduction | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Neutropenia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypokalemia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Complications | ||||||

| Pancreatitis | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ascites | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Bleeding from duodenal ulcer | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Portal vein thrombosis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Loss of appetite | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Gastroparesis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Abdominal pain | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

In this study, we found that GEM plus concurrent IRE improved the therapeutic efficacy compared to conventional GEM alone. The GEM + IRE group had significantly longer time to OS and PFS. Additionally, GEM plus concurrent IRE treatment and tumor volume less than 37 cm3 were considered significant independent predictors of survival. Although certain major complications have been identified in our patients, we believe that the use of appropriate measures can help prevent these complications. GEM plus concurrent IRE was a safe and effective treatment for patients with LAPC.

Patients with LAPC who cannot undergo radical surgical resection have experienced a limited response to conventional therapy and an extremely poor prognosis[15]. IRE ablation with a unique non-thermal killing mechanism brings hope for the treatment of LAPC. During the ablation process, there is no serious damage to the extracellular matrix. Subsequently, the ablation zone undergoes a process of proliferation and repair, and was eventually replaced by normal tissue, resulting in more effective treatment[16-19]. Chemotherapy is the current standard for treating LAPC, and chemotherapeutic drug penetration remains challenging due to the heterogeneity of malignant tumors. Therefore, the primary purpose of this study was to elucidate whether IRE can be used as an adjunct to chemotherapy and optimize the therapeutic effect. In addition, previous studies have focused on induction chemotherapy followed by resection or IRE, whereas we focused on whether GEM plus concurrent IRE treatment has a synergistic effect[20-22]. Our study was based on a seminal animal experiment that suggested that IRE can increase drug delivery to the tissue in the reversible electroporation zone[23].

IRE has been proven to be a safe and effective alternative option for advanced pancreatic cancer[24-26]. However, the majority of studies were retrospective and were not compared with standard treatment. The median OS from diagnosis ranged from 17.9 to 32.0 mo for these retrospective studies. In our study, the median OS was 19.8 mo from the time of diagnosis for GEM + IRE group. There are several reasons to explain this difference. The most important point was that patients received preoperative chemotherapy or chemoradiation therapy before IRE ablation and had proven stable[21,27]. Furthermore, the condition of the patients has remained stabilized, which achieves a better therapeutic effect and the tumor size of patients is typically around 3 cm. In a study using IRE as a first-line treatment for LAPC with a median of 13.3 mo, unlike this, we used GEM plus concurrent IRE for LAPC and prolonged survival[28]. In another study, the treatment effect was better and the median overall survival was 24.9 mo[25]. A possible explanation could be that all patients were treated with chemotherapy and/or radiation chemotherapy prior to IRE treatment. In addition, they performed diagnostic laparoscopy before treatment to rule out peritoneal metastatic disease. Twenty-five percent of their patients underwent resection during IRE treatment. In our study, IRE was performed percutaneously without precursory laparoscopy. Therefore, we may have included patients with disseminated disease. Thus, diagnostic laparoscopy prior to percutaneous IRE may be necessary.

In our study, 29 (82.8%) patients presented tumor progression after chemotherapy and 15 (45.4%) patients presented tumor progression after GEM plus concurrent IRE. GEM plus concurrent IRE resulted in significantly longer PFS compared with chemotherapy alone, mainly because IRE enhances the concentration of GEM in the pancreatic tissue reversible zone, for which the membrane penetration caused by electroporation promotes drug diffusion to cells and increases drug cytotoxicity[23,29]. Therefore, the patients underwent no less than 30 min of an intravenous infusion of GEM (1000 mg/m2) prior to IRE ablation in our study. The target time of 2 to 4 wk post-IRE was followed by GEM chemotherapy, which was determined according to the post-IRE physical recovery of the patient. Pancreatic cancer is a systemic heterogeneous tumor, which does not respond to traditional chemotherapy. In addition, IRE is only a regional physical ablation technique. Therefore, GEM plus concurrent IRE has a synergistic effect on the clinical treatment of LAPC.

In this study, there were three major complications; two (6%) patients experienced pancreatitis (grade IV) and one (3%) had duodenal bleeding (grade III). Similar severe digestive tract bleeding associated with duodenal ulcer has also occurred in other studies with an occurrence rate of 4%-7%[12,21]. Thus, the scope of safety in the application of IRE ablation of pancreatic head tumors that invade the duodenum should still be carefully considered. Although IRE ablation will not cause irreversible damage to the vascular structure, the release of electrical pulses can cause reversible damage to vascular endothelial cells. These damaged epithelial cells comprise the lining of smooth blood vessels, reduce blood flow, and cause thrombosis in the portal vein system formation, especially for patients who have tumors that have invaded the portal vein and narrowed the lumen before surgery. Complications of portal vein thrombosis have also been found in other studies and stated that post-operative inflammation is the main cause of portal vein cancer thrombosis[25,30,31].

To our knowledge, this is the first prospective randomized trial to compare treatment with GEM plus concurrent IRE and GEM alone in LAPC. Based on our findings, GEM plus concurrent IRE can help guide treatment decisions for patients with LAPC.

In conclusion, GEM plus concurrent IRE can improve therapeutic efficacy with fewer complications, which provides a safe and effective method for the clinical treatment of LAPC. However, since the clinical sample data are relatively small in this study, further large sample analysis is required to verify these findings.

Locally advanced pancreatic cancer (LAPC) is a common malignant digestive system tumor. Surgery and chemotherapy remain the primary treatments for patients with LAPC, however, the outcome is not always satisfactory. Irreversible electroporation (IRE) is an emerging physical ablation technology that uses high voltage short pulses to destroy the integrity of the cell membrane, resulting in cell apoptosis. To date, however, there has been a lack of prospective data to verify the therapeutic outcome of gemcitabine (GEM) plus concurrent IRE.

We hope to explore whether GEM plus concurrent IRE has a synergistic effect on the clinical treatment of LAPC.

To compare the therapeutic efficacy between conventional GEM plus concurrent IRE and GEM alone for LAPC.

This prospective study (NCT02981719) was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Affiliated Fuda Cancer Hospital, Jinan University. From February 2016 to September 2017, the included patients were treated with GEM plus concurrent IRE (n = 33, median age = 63) or GEM alone (n = 35, median age = 65). The largest median tumor diameter was 4.1 cm and 3.9 in the GEM + IRE and GEM alone group, respectively. Overall survival (OS), progression free survival (PFS), and procedure-related complications were compared between the two groups. Multivariate analyses were performed to identify any prognostic factors.

There were no treatment-related deaths. The technical success rate of IRE ablation was 100%. The median OS was 19.8 and 9.3 mo from the time of diagnosis in the GEM + IRE group and GEM alone group, respectively. The median PFS was 8.3 and 4.7 mo for the GEM + IRE group and GEM alone group, respectively. Tumor volume less than 37 cm3 and GEM plus concurrent IRE were identified as significant favorable factors for both the OS and PFS. Although certain major complications have been identified in our patients, we believe that the use of appropriate measures can help prevent these complications.

GEM plus concurrent IRE can improve therapeutic efficacy with fewer complications, which provides a safe and effective method for the clinical treatment of LAPC.

We focused on whether GEM plus concurrent IRE treatment has a synergistic effect. Our data demonstrate that GEM plus concurrent IRE is a safe and effective method for the clinical treatment of LAPC.

We would like to acknowledge the participating patients and their families, physicians, and the data and coordination center for continuous support.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Xu M S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12667] [Cited by in RCA: 15255] [Article Influence: 3051.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 2. | Chao Y, Wu CY, Wang JP, Lee RC, Lee WP, Li CP. A randomized controlled trial of gemcitabine plus cisplatin versus gemcitabine alone in the treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;72:637-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tempero MA, Malafa MP, Chiorean EG, Czito B, Scaife C, Narang AK, Fountzilas C, Wolpin BM, Al-Hawary M, Asbun H, Behrman SW, Benson AB, Binder E, Cardin DB, Cha C, Chung V, Dillhoff M, Dotan E, Ferrone CR, Fisher G, Hardacre J, Hawkins WG, Ko AH, LoConte N, Lowy AM, Moravek C, Nakakura EK, O'Reilly EM, Obando J, Reddy S, Thayer S, Wolff RA, Burns JL, Zuccarino-Catania G. Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma, Version 1.2019. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17:202-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 270] [Article Influence: 54.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 4. | Burris HA, Moore MJ, Andersen J, Green MR, Rothenberg ML, Modiano MR, Cripps MC, Portenoy RK, Storniolo AM, Tarassoff P, Nelson R, Dorr FA, Stephens CD, Von Hoff DD. Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2403-2413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4351] [Cited by in RCA: 4170] [Article Influence: 148.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Huguet F, André T, Hammel P, Artru P, Balosso J, Selle F, Deniaud-Alexandre E, Ruszniewski P, Touboul E, Labianca R, de Gramont A, Louvet C. Impact of chemoradiotherapy after disease control with chemotherapy in locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma in GERCOR phase II and III studies. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:326-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 402] [Cited by in RCA: 369] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Loehrer PJ Sr, Feng Y, Cardenes H, Wagner L, Brell JM, Cella D, Flynn P, Ramanathan RK, Crane CH, Alberts SR, Benson AB 3rd. Gemcitabine alone versus gemcitabine plus radiotherapy in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer: an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4105-4112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 578] [Cited by in RCA: 620] [Article Influence: 44.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Min G, Choi HS, Kim W, Choi SJ, Chang DK. Development of new endoscopic irreversible electroporation ablation device: Animal experimental study. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:188-188. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Liehr UB, Wendler JJ, Blaschke S, Porsch M, Janitzky A, Baumunk D, Pech M, Fischbach F, Schindele D, Grube C, Ricke J, Schostak M. [Irreversible electroporation: the new generation of local ablation techniques for renal cell carcinoma]. Urologe A. 2012;51:1728-1734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ruarus A, Vroomen L, Puijk R, Scheffer H, Meijerink M. Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer: A Review of Local Ablative Therapies. Cancers (Basel). 2018;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Scheffer HJ, Nielsen K, de Jong MC, van Tilborg AA, Vieveen JM, Bouwman AR, Meijer S, van Kuijk C, van den Tol PM, Meijerink MR. Irreversible electroporation for nonthermal tumor ablation in the clinical setting: a systematic review of safety and efficacy. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2014;25:997-1011; quiz 1011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 276] [Cited by in RCA: 278] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | de Liguori Carino N, O'Reilly DA, Siriwardena AK, Valle JW, Radhakrishna G, Pihlak R, McNamara MG. Irreversible Electroporation in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: Is there a role in conjunction with conventional treatment? Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44:1486-1493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Vogel JA, Rombouts SJ, de Rooij T, van Delden OM, Dijkgraaf MG, van Gulik TM, van Hooft JE, van Laarhoven HW, Martin RC, Schoorlemmer A, Wilmink JW, van Lienden KP, Busch OR, Besselink MG. Induction Chemotherapy Followed by Resection or Irreversible Electroporation in Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer (IMPALA): A Prospective Cohort Study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:2734-2743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1471-1474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5537] [Cited by in RCA: 6439] [Article Influence: 429.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Nielsen K, Scheffer HJ, Vieveen JM, van Tilborg AA, Meijer S, van Kuijk C, van den Tol MP, Meijerink MR, Bouwman RA. Anaesthetic management during open and percutaneous irreversible electroporation. Br J Anaesth. 2014;113:985-992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Martin RC 2nd, McFarland K, Ellis S, Velanovich V. Irreversible electroporation in locally advanced pancreatic cancer: potential improved overall survival. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20 Suppl 3:S443-S449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Charpentier KP, Wolf F, Noble L, Winn B, Resnick M, Dupuy DE. Irreversible electroporation of the liver and liver hilum in swine. HPB (Oxford). 2011;13:168-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Silk MT, Wimmer T, Lee KS, Srimathveeravalli G, Brown KT, Kingham PT, Fong Y, Durack JC, Sofocleous CT, Solomon SB. Percutaneous ablation of peribiliary tumors with irreversible electroporation. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2014;25:112-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Schoellnast H, Monette S, Ezell PC, Maybody M, Erinjeri JP, Stubblefield MD, Single G, Solomon SB. The delayed effects of irreversible electroporation ablation on nerves. Eur Radiol. 2013;23:375-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Narayanan G, Hosein PJ, Arora G, Barbery KJ, Froud T, Livingstone AS, Franceschi D, Rocha Lima CM, Yrizarry J. Percutaneous irreversible electroporation for downstaging and control of unresectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012;23:1613-1621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | He C, Wang J, Sun S, Zhang Y, Lin X, Lao X, Cui B, Li S. Irreversible electroporation versus radiotherapy after induction chemotherapy on survival in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer: a propensity score analysis. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Månsson C, Brahmstaedt R, Nilsson A, Nygren P, Karlson BM. Percutaneous irreversible electroporation for treatment of locally advanced pancreatic cancer following chemotherapy or radiochemotherapy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42:1401-1406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Narayanan G, Hosein PJ, Beulaygue IC, Froud T, Scheffer HJ, Venkat SR, Echenique AM, Hevert EC, Livingstone AS, Rocha-Lima CM, Merchan JR, Levi JU, Yrizarry JM, Lencioni R. Percutaneous Image-Guided Irreversible Electroporation for the Treatment of Unresectable, Locally Advanced Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2017;28:342-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bhutiani N, Agle S, Li Y, Li S, Martin RC 2nd. Irreversible electroporation enhances delivery of gemcitabine to pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2016;114:181-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Scheffer HJ, Vroomen LG, de Jong MC, Melenhorst MC, Zonderhuis BM, Daams F, Vogel JA, Besselink MG, van Kuijk C, Witvliet J, de van der Schueren MA, de Gruijl TD, Stam AG, van den Tol PM, van Delft F, Kazemier G, Meijerink MR. Ablation of Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer with Percutaneous Irreversible Electroporation: Results of the Phase I/II PANFIRE Study. Radiology. 2017;282:585-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Martin RC 2nd, Kwon D, Chalikonda S, Sellers M, Kotz E, Scoggins C, McMasters KM, Watkins K. Treatment of 200 locally advanced (stage III) pancreatic adenocarcinoma patients with irreversible electroporation: safety and efficacy. Ann Surg. 2015;262:486-94; discussion 492-4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 255] [Cited by in RCA: 292] [Article Influence: 29.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sugimoto K, Moriyasu F, Tsuchiya T, Nagakawa Y, Hosokawa Y, Saito K, Tsuchida A, Itoi T. Irreversible Electroporation for Nonthermal Tumor Ablation in Patients with Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer: Initial Clinical Experience in Japan. Intern Med. 2018;57:3225-3231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Leen E, Picard J, Stebbing J, Abel M, Dhillon T, Wasan H. Percutaneous irreversible electroporation with systemic treatment for locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2018;9:275-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Gibot L, Wasungu L, Teissié J, Rols MP. Antitumor drug delivery in multicellular spheroids by electropermeabilization. J Control Release. 2013;167:138-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | MÅNSSON C, Brahmstaedt R, Nygren P, Nilsson A, Karlson BM. Percutaneous Irreversible Electroporation as First-line Treatment of Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2019;2509-2512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Paiella S, Butturini G, Frigerio I, Salvia R, Armatura G, Bacchion M, Fontana M, D'Onofrio M, Martone E, Bassi C. Safety and feasibility of Irreversible Electroporation (IRE) in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer: results of a prospective study. Dig Surg. 2015;32:90-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Martin RC. Irreversible electroporation of locally advanced pancreatic head adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:1850-1856. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |