Published online Nov 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i21.5361

Peer-review started: June 15, 2020

First decision: July 25, 2020

Revised: July 28, 2020

Accepted: September 22, 2020

Article in press: September 22, 2020

Published online: November 6, 2020

Processing time: 143 Days and 19.8 Hours

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 has been confirmed to be a newly discovered zoonotic pathogen that causes highly contagious viral pneumonia, which the World Health Organization has named novel coronavirus pneumonia. Since its outbreak, it has become a global pandemic. During the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), however, there is no mature experience or guidance on how to carry out emergency surgery for suspected cases requiring emergency surgical intervention and perioperative safety protection against virus.

A 41-year-old man was admitted to the hospital for emergency treatment due to "3-d abdominal pain aggravated with cessation of exhaust and defecation". After improving inspections and laboratory tests, the patient was assessed and diagnosed by the multiple discipline team as "strangulation obstruction, pulmonary infection”. His body temperature was 38.8 °C, and the chest computed tomography showed pulmonary infection. Given fever and pneumonia, we could not rule out COVID-19 after consultation by fever clinicians and respiratory experts. Hence, we performed emergency surgery under three-level protection for the suspected case. After surgery, his nucleic acid test for COVID-19 was negative, meaning COVID-19 was excluded, and routine postoperative treatment and nursing was followed. The patient was treated with symptomatic support after the operation. The stomach tube and urinary tube were removed on the 1st d after the operation. The clearing diet was started on the 3rd d after the operation, and the body temperature returned to normal. Flatus and bowel movements were noted on 5th postoperative day. He was discharged after 8 d of hospitalization. The patient was followed up for 4 mo after discharge, no serious complications occurred. A 71-year-old woman was admitted to our emergency room due to "abdominal distention, fatigue for 6 d and fever for 13 h". After the multiple discipline team evaluation, the patient was diagnosed as "intestinal obstruction, abdominal mass, peritonitis and pulmonary infection". At that time, the patient's body temperature was 39.6 °C, and chest computed tomography indicated pulmonary infection. COVID-19 could not be completely excluded after consultation in the fever outpatient department and respiratory department. Therefore, the patient was treated as a suspected case, and an urgent operation was performed under three-level medical protection. Postoperative nucleic acid test was negative, COVID-19 was excluded, and routine postoperative treatment and nursing were followed. After the operation, the patient received symptomatic and supportive treatment. The gastric tube was removed on the 1st d after the operation, and the urinary tube was removed on the 3rd d after the operation. Enteral nutrition began on the 3rd d after the operation. To date, no serious complications have been found during follow-up after discharge.

Based on the previous treatment experience, we reviewed the procedures of two cases of suspected COVID-19 emergency surgery and extracted the perioperative protection experience. By referring to the literature and following the regulations on prevention and management of infectious diseases, we have developed a relatively mature and complete emergency surgical workflow for suspected COVID-19 cases and shared perioperative protection and management experience and measures.

Core Tip: During the pandemic period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), we reviewed the procedures of two cases of suspected COVID-19 emergency surgery and extracted the perioperative protection experience. We developed a relatively mature and complete emergency surgical workflow for suspected COVID-19 cases and shared perioperative protection and management experience and measures. As COVID-19 continues to ravage the world, health care workers can both protect themselves from COVID-19 infection and do their best to save the lives of critical, urgent and suspected COVID-19 patients by following reasonable and effective workflow of emergency surgery and adopting mature perioperative safety precautions.

- Citation: Wu D, Xie TY, Sun XH, Wang XX. Emergency surgical workflow and experience of suspected cases of COVID-19: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(21): 5361-5370

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i21/5361.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i21.5361

The ongoing pandemic caused by a novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia has generated great concern in the international community. It has been confirmed to be a highly contagious disease caused by a zoonotic pathogen novel coronavirus: Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)[1-4]. A majority of scholars also called it novel coronavirus pneumonia or novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in the early stage of the epidemic before the World Health Organization officially named it coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)[1,2,5]. Epidemiological studies have found that people are generally susceptible to COVID-19, and confirmed COVID-19 patients are clearly the source of infection of this disease, which is transmitted from person to person through respiratory droplets and close contact[6,7]. Meanwhile, aerosol transmission and fecal-oral transmission may also exist[7-9]. As with most respiratory viruses, it is considered most contagious when the patient is symptomatic, but SARS-CoV-2 has been transmitted by asymptomatic or presymptomatic carriers, although how frequently remains uncertain[10-12]. Based on the initial data of the epidemiologic characteristics of COVID-19 published on the New England Journal of Medicine, the basic reproductive number (R0) was estimated to be 2.2 (95% confidence interval, 1.4-3.9)[13]. However, another analysis showed that R0 even reached 3.6-4.0[11], indicating that COVID-19 was highly contagious. To date, COVID-19 has formed a global pandemic, the number of confirmed people is still rising, and the global epidemic prevention and control situation is grim. In accordance with the requirements[14] of prevention and control during the outbreak of COVID-19, we reduced selective surgical treatments but not emergency surgery and cancer surgery, which significantly affect the prognosis of patients. General surgery involves a wide scope of organs, common emergencies mainly endanger the life of patients with acute abdominal pain and abdominal trauma, and aggressive surgical intervention is the only effective means of rescue. However, a lot of emergency patients are often accompanied by fever, chest tightness, even dyspnea, etc., which are common symptoms of COVID-19[15]. Combined with hysteresis of SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid testing results, sometimes it is hard to distinguish COVID-19 from other causes of the mentioned respiratory symptoms. In patients suspected to have COVID-19 who require urgent surgery, the risks and benefits of proceeding or postponing need to be weighed. To reduce risks to both patient and hospital staff, only emergency surgery should be performed on suspected patients[16]. Currently, there is no relevant regulations and guidelines on the management of emergency surgery for suspected COVID-19 cases and the perioperative protection against infection for medical staff. It is a significant challenge to ensure the safety of medical workers, make sure “zero infection”, and carry out standardized emergency surgery to the greatest extent during COVID-19 epidemic. Combined with the experience of emergency surgery of two suspected COVID-19 cases, we summarized the emergency surgical procedures and vital experience of general surgery during the epidemic of COVID-19 in order to provide references and suggestions for emergency surgery and perioperative protection during the epidemic period.

A 41-year-old man presented to the Emergency Department of our hospital complaining of 3-d abdominal pain aggravated with cessation of exhaust and defecation. Another case was a 71-year-old woman admitted to our emergency room due to abdominal distention, fatigue for 6 d and fever for 13 h.

The first patient’s symptoms started 3 d ago with mid-abdominal pain, which had worsened the last 24 h along with cessation of venting and defecating. The second patient developed general fatigue, abdominal distension, and poor appetite without obvious inducement 6 d ago. The patient also complained of palpable lumps in the lower abdomen. Nausea and vomiting occurred once that day, along with fever and a cough with a small amount of white phlegm. Since then, the patient's symptoms gradually worsened, and suddenly her abdominal pain could not be relieved and was accompanied by fever and mild consciousness disorder. Her son brought her to the emergency department for further treatment.

The first patient underwent laparoscopic appendectomy for acute appendicitis 5 years ago and recovered well after the operation. That same year, he recovered after medical treatment for acute pancreatitis. Second patient had a hysteromyomectomy 30 years ago, and a brain pacemaker implanted 1 year ago because of a 30-year history of Parkinson’s disease.

The first patient’s temperature was 38.8 °C, heart rate was 92 bpm, respiratory rate was 18 breaths per min, blood pressure was 101/66 mmHg, and body mass index (BMI) was 24.2. Physical examination revealed a surgical scar on the right lower abdomen. The abdomen was flat with muscle tension, and there was tenderness around the navel, but rebound pain was not obvious. Abdominal mobile dullness was negative, and bowel sounds were weak for 1-3 times per min. The second patient’s temperature was 39.6 °C, heart rate was 91 bpm, respiratory rate was 18 breaths per min, blood pressure was 128/62 mmHg, and BMI was 24.5. Physical examination revealed abdominal distension, abdominal muscle tension, and tenderness; rebound pain was not obvious, mobile dullness was negative, and bowel sounds were weak 1-3 times per min.

First patient’s routine blood examination revealed: Hemoglobin 127 g/L, white blood cell count 14.38 × 109/L ↑, neutrophil 0.895 ↑, lymphocyte 0.217, platelet count 265 × 109/L, and serum C-reactive protein 6.8 mg/dL ↑; blood biochemical examination: Alanine aminotransferase 34.6 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase 29.8 U/L, total protein 68.7 g/L, serum albumin 38.9 g/L, serum potassium 3.42 mmol/L ↓, and remaining electrolytes were basically normal. Prothrombin and partial thromboplastin times were normal, and d-dimers were slightly increased at 0.89 μg/mL. Electrocardiogram was normal. Second patient’s routine blood examination revealed: Hemoglobin 109 g/L ↓, white blood cell count 17.56 × 109/L ↑, neutrophil count 0.915 ↑, lymphocyte 0.197 ↓, platelet count 235 × 109/L, and C-reactive protein 7.8 mg/dL ↑; blood biochemical examination: Alanine aminotransferase 12.6 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase 36.3 U/L, total protein 57.7 g/L, serum albumin 35.1 g/L, glucose 8.79 mmol/L ↑, and remaining electrolytes were basically normal.

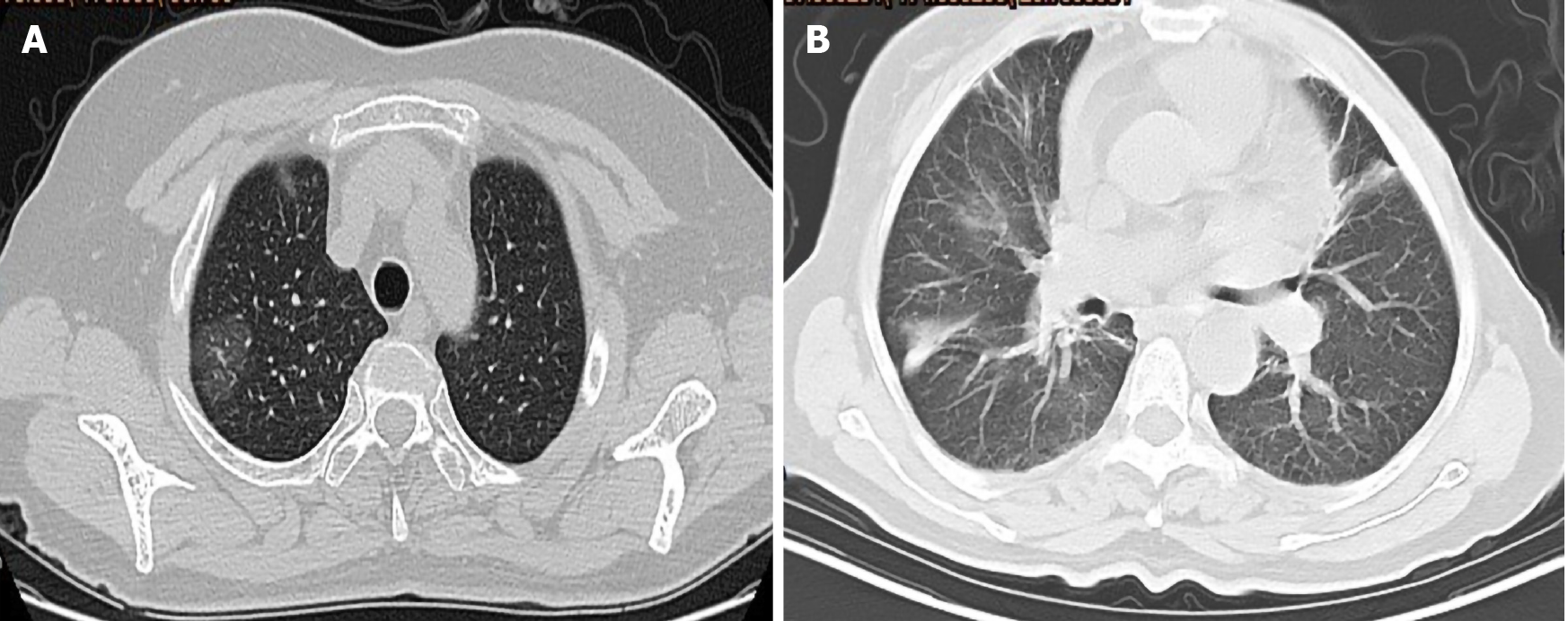

First patient’s abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan revealed: (1) Small bowel dilatation and effusion (based on combined clinical observation and dynamic observation); (2) The fat space around the pancreas was slightly blurred (clinical and laboratory tests were combined to exclude pancreatitis), consistent with mild fatty liver; (3) Multiple calcifications in the liver; and (4) Possibility of gallbladder stones; left kidney stone. Chest CT is shown in Figure 1A, and radiographic images of both lungs suggested the possibility of infectious lesions.

Second patient’s chest CT indicated pulmonary infection (Figure 1B). Abdominal CT scan showed obvious dilation in the small intestine, and there were abnormal air fluid levels in the small bowel. Gallbladder volume was increased, gallbladder wall was slightly thickened, fat spaces around the pancreas were blurred, and there was a small amount of liquid density shadow around the liver.

The final diagnosis of the first case was strangulation obstruction and pulmonary infection. The final diagnosis of the second case was abdominal neoplasm, strangulation obstruction, and pulmonary infection.

Given fever and pneumonia, we could not rule out COVID-19, although fever clinicians and respiratory experts were consulted. Hence, we performed emergency surgery under three-level protection for the suspected cases. After laparotomy under general anesthesia, the first patient was observed with extensive abdominal adhesions, partial small intestinal congestion and edema, and blackened and necrotic intestinal tube of about 230 cm. The adhesive tissues were released, the small intestine was partially excised, and the side anastomosis was performed. The second patient’s abdominal exploration operation under the three-level medical protection revealed a large amount of yellowish clear ascites in the abdominal cavity, extensive omental edema, and adhesion covering the right lower abdomen. After separation, a huge cystic mass, about 10 cm in diameter, was seen. According to the results of the investigation, we decided to perform partial resection of the small intestine, anastomosis, and peritoneal cyst resection. After the operation, the two patients were given anti-inflammatories, nutrition, and other symptomatic support treatment. Novel coronavirus nucleic acid test was also performed.

After surgery, the first patient's nucleic acid test for COVID-19 was negative, meaning COVID-19 was excluded, and routine postoperative treatment and nursing was followed. The patient was treated with symptomatic support after the operation. The stomach tube and urinary tube were removed on the 1st d after the operation. The clearing diet was started on the 3rd d after the operation, and the body temperature returned to normal. Flatus and bowel movements were noted on the 5th postoperative day. He was discharged after 8 d of hospitalization. The patient was followed up for 4 mo after discharge, and no serious complications occurred.

The second patient received symptomatic and supportive treatment after surgery. Her gastric tube was removed on the 1st d after the operation, and the urinary tube was removed on the 3rd d after the operation. Enteral nutrition began on the 3rd d after the operation. Her pathology confirmed a small intestinal stromal tumor. To date, no serious complications have been found during follow-up after discharge.

Acute abdomen and abdominal trauma in general surgery are often highly time-dependent, and patients undergoing emergency treatment should be fully examined and evaluated, and the necessary surgical interventions should be carried out in time. Patients with fever, chest tightness, and dyspnea who are admitted to the emergency department during the epidemic must undergo chest CT examination, viral nucleic acid testing if necessary, and undergo multi-disciplinary evaluation. Risks and benefits of proceeding or postponing an emergency surgery need to be weighed, and only patients with serious fatal illness are selected to undergo emergency surgery if there is a suspicion of COVID-19. A study examining the correlation of chest CT and RT-PCR testing in COVID-19 indicated that approximately 60%-93% of confirmed cases had initial positive CT findings consistent with COVID-19 prior (or parallel) to the initial positive RT-PCR (viral nucleic acid testing) results[17]. Therefore, because of the hysteresis and false negatives of viral nucleic acid detection, chest CT scanning may be useful as a primary or complement method for the rapid diagnosis of COVID-19 to optimize the management of patients[17-19]. In addition, the COVID-19 Diagnosis and Treatment Program (Trial Version 5)[20] issued by the Chinese National Health and Health Commission added the concept of clinical diagnosis, emphasizing chest CT examination for suspected cases.

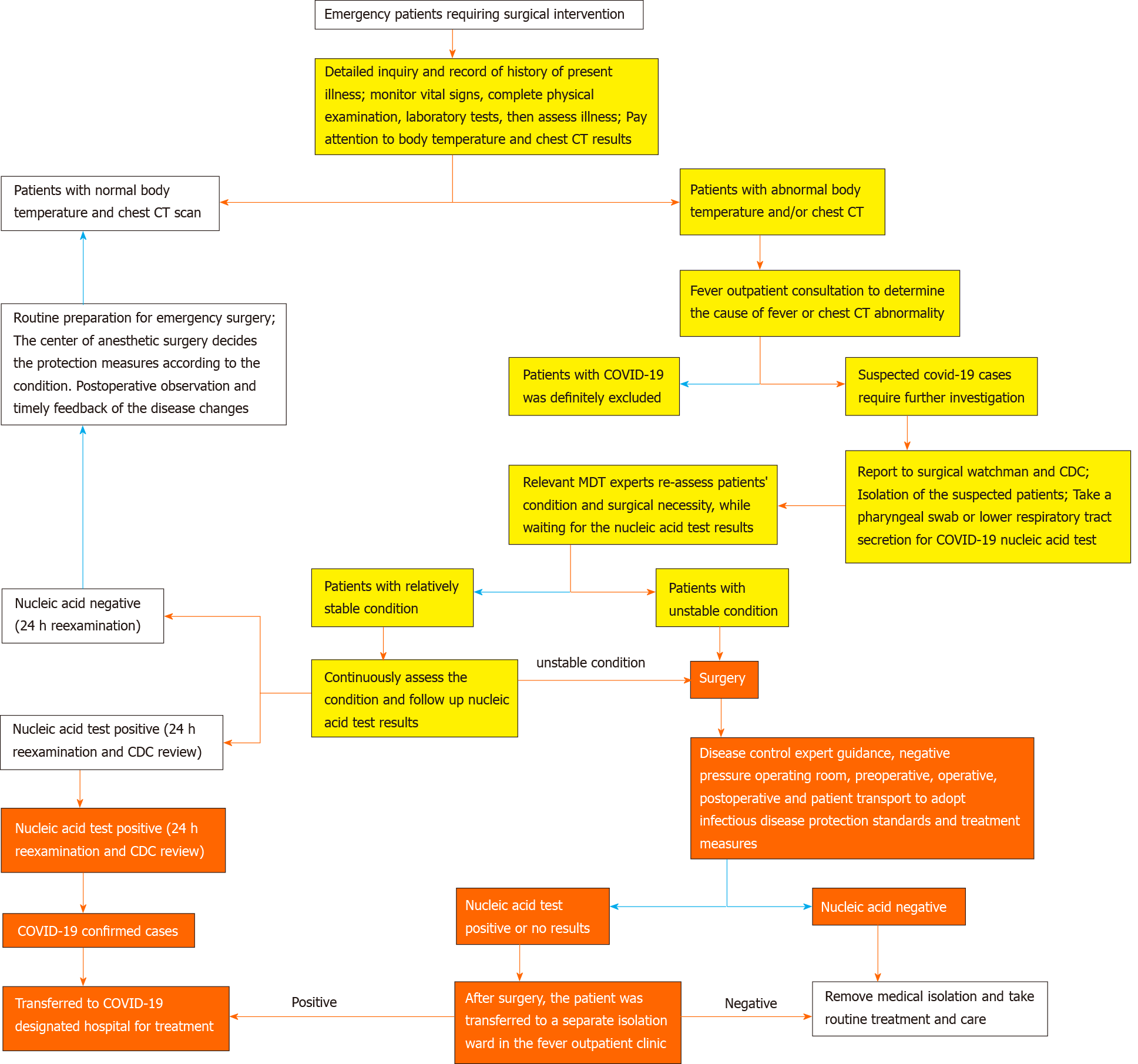

Many studies[17-21] have argued that the chest CT manifestations of COVID-19 are divided into early stage, advanced stage, and severe stage. In the early stage, it was a single or multiple ground glass opacity, and the scope of the disease in the advanced stage expanded into consolidation with or without vascular enlargement. In the severe stage, the density of the two lungs was diffusely uneven or "white lung". With the progression of the disease, the chest CT manifestations gradually increase with time, further showing that chest CT manifestations can reflect disease progression and may have a certain suggestive effect on disease prognosis. Combining the experience of two emergency treatments for suspected cases, we believe that a comprehensive evaluation of the patient's clinical manifestations, laboratory examinations, and chest CT manifestations is a prerequisite for correct decision-making. For patients that cannot be excluded from COVID-19 after evaluation by the multidisciplinary treatment collaboration group (MDT) team, we recommend that they should be treated as suspected cases. We drew up a “flow chart of treatment and management of emergency patients requiring surgical intervention during COVID 19 epidemic” (Figure 2) to provide a reference for the management and treatment of other similar cases during the subsequent outbreak. What needs to be emphasized is the recommendation to adopt second-level or third-level protection for first-aid medical staff, imaging doctors, and throat swab collection nurses. Patients with unstable conditions need to be actively intervened and treated after evaluation in the shortest possible time. Patients with a relatively stable condition at the time of treatment should be continuously and dynamically assessed of their condition. If the disease progresses or hemodynamic instability is found, decisive and effective surgical intervention is required.

When suspected infection cases are admitted to the emergency department during the epidemic and the condition is unstable and life-threatening or the prognosis is poor, emergency surgery is required. The perioperative preparation and safety protection requirements for such patients are different from those for routine emergency preparation.

Operating room preparation: We have already known that respiratory droplets and close contact transmission are the main transmission routes for COVID-19. Aerosol transmission is possible when exposed to a high concentration of aerosol for a long time in a relatively closed environment. Since coronavirus can be isolated in urine and feces, attention should be paid to the aerosol or contact transmission caused by urine and feces to environmental pollution. A dedicated operating room with a negative pressure (-5 Pa or less) environment is ideal for suspected or confirmed cases to reduce dissemination of the virus beyond the operating room[22,23]. The negative pressure operating room should have a separate access channel to isolate it from other operating rooms and set the isolation and buffer area. The buffer zone was closed during the operation, and a prominent sign was posted at the door of the operation. If a negative pressure operating room is unavailable, an operating room with an independent purification system and a relatively independent space should be selected, and terminal disinfection should be performed as required after surgery.

Surgical staff preparation: The number of staff participating in the operation should be restricted to the minimum necessary for patient safety. We recommend the operation team consists of surgeons (two to three people), anesthesiologists (one person), and nurses (two people); all staff should be protected in appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE). Designated areas were prepared for donning and doffing of PPE. Steps were numbered in sequence, and posters were put up to guide staff. Under the supervision and guidance of the disease control department, the medical staff and anesthesiologists participating in the operation wore PPE according to the requirements of three-level protection[24] according to the "procedures for medical staff to wear and take off protective equipment" before operation: Double-layer disposable hat, N95 mask, medical protective clothing, disposable isolation surgical gown, goggles, medical shield, and double-layer sterile gloves. After all members were properly protected, the doctor wearing PPE escorted the patient to the operating room through a dedicated channel or elevator.

Intraoperative anesthesia management and protection: The process of anesthesia intubation and extubation is the key link for the emergence of droplet exposure, and an experienced anesthesiologist should be selected to participate in the operation. Visual intubation tools and disposable endotracheal intubation tools are recommended. Non-disposable intubation tools should be strictly disinfected after use. Before anesthesia induction, artificial nasal breathing filters were installed between the anesthesia mask and the breathing circuit as well as the inhalation and exhalation ends of the anesthesia machine[25]. During anesthesia induction, special attention should be paid to adjust the flow of oxygen inhalation to avoid environmental pollution, fully relax the muscles, and use rapid induction techniques to avoid choking during intubation. It is important to strive for a successful one-time intubation. If a difficult airway is encountered, a laryngeal mask should be placed after the intubation fails to avoid repeated attempts of intubation. After successful anesthesia, the anesthesiologist should change disposable sterile gloves.

After the operation, the patient is recommended to bring the tracheal catheter and artificial nose to the intensive care unit (ICU) isolation ward of the fever clinic. If extubation is required after surgery, the airway secretions should be cleared in advance under deep anesthesia to avoid choking caused by cleaning the airway. It is recommended to choose the timing of extubation when the patient's consciousness has not been restored but has resumed regular spontaneous breathing. When extubating, attention should be given to retaining the artificial nose at the end of the tracheal tube, which can prevent the spray of airway secretions from causing droplets and aerosol contamination.

Surgical procedure management and protection: During the operation, electrocautery, ultrasonic knife, aspiration device, and other operations will inevitably produce a large amount of aerosol. At the same time, due to poor gas flow in the pneumoperitoneum, a large amount of aerosol smoke particles accumulate in the abdominal cavity. Because of the positive pressure of the pneumoperitoneum, the aerosol will be suddenly released with the opening of the trocar hole or a small abdominal incision, which increases the risk of aerosol exposure for the surgical staff. The surgical method should choose a simple and fast operation method to shorten the operation time and reduce the risk of intraoperative exposure. We prefer laparotomy should follow the principle of injury control[26]. Laparoscopic surgery can also be selected according to the needs of the disease and pneumoperitoneum and aerosol management should be performed during the operation.

Although the use of PPE in the operation guarantees the safety of the medical staff, it also comes with a lot of inconveniences. The multi-layer protective measures reduce the visual, auditory, and tactile sensitivities of the medical staff, which reduces the accuracy of the operation. As the operation progresses and the time is extended, fogging of the goggles may seriously affect the sight of the medical staff and increase the chance of intraoperative contamination. To solve this problem, medical antibacterial hand sanitizer or iodophor to coat evenly the inside and outside of the goggle lenses can be used, and paper towels can be used to wipe off excess hand sanitizer or iodophor. This method can reduce the fogging of the goggles during the operation.

During the operation, medical staff should operate gently to avoid splashing of blood, body fluids, flushing fluid, and drainage fluid and pay attention to the power of the energy equipment. The chief physician, assistant, and equipment nurse should cooperate skillfully and carefully. For example, when using a threaded needle for suture operation during surgery, it is recommended to use scissors to cut the thread to avoid the embarrassment of skipping the needle and losing the needle when pulling the suture improperly. Surgery team members should avoid occupational exposure caused by needle stick injuries or sharp device injuries during surgery.

Postoperative transport and management of patients: After the operation, the patient should be transferred to the ICU isolation ward by medical staff wearing three-level PPE according to the originally set transfer channel or elevator. Pay attention to protection on the way to avoid accidental exposure during transit. After the operation, the patient's nucleic acid test results were continuously tracked. If the test result is negative (retest after 24 h), the medical isolation can be lifted. If the test result is positive (retest after 24 h), the patient should be transported to the designated hospital for further treatment.

Management of specimens and related surgical items after surgery: Postoperative specimens are recommended to be immersed in formaldehyde and made a "COVID-19 suspect" eye-catching record and then sent to the Pathology Department by a special person. Disposables, medical protective equipment, and blood, body fluids, and rinsing fluids generated during the operation were placed in double-layer yellow medical waste bags and sealed, and the "COVID-19 suspect" logo was affixed on the outside. These items were treated as infectious medical wastes according to relevant regulations. Surgical instruments were packaged in double-layer yellow medical waste bags, which were affixed with an eye-catching “COVID-19 suspect” logo and sterilized separately. After the operation, the floor of the operating room, the operating table, and various equipment should be thoroughly disinfected.

Postoperative management of medical staff: The medical staff involved in the operation should take off the protective clothing after the operation under the supervision and guidance of a dedicated person and leave through a dedicated passage. The results of nucleic acid detection of patients should be followed up after surgery. Surgical staff without accidental exposure during the entire perioperative period can be exempted from medical isolation, otherwise a 14-d medical isolation observation should be performed.

During the epidemic, emergency doctors should pay special attention to the differential diagnosis of acute and serious diseases in general surgery, assess the patient's condition continuously and dynamically, and strictly control the indications for surgery. It is recommended to form a MDT with the relevant departments such as emergency department, fever clinic, general surgery, radiology department, anesthesia operation center, ICU isolation ward, disease control department, etc. Comprehensive evaluation of patients through MDT discussion should be performed to determine a reasonable diagnosis and treatment plan. In order to ensure the safety of medical staff, the online platform can be used for discussion, disease evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment plan formulation during COVID-19 pandemic. For patients suspected with COVID-19, we can follow the flowchart of treatment and management of emergency patients requiring surgical intervention during COVID-19 epidemic period. Medical staff should pay attention to the management and protection of the perioperative period to avoid exposure during the operation. These containment measures are necessary to optimize the quality of care provided to patients confirmed or suspected COVID-19 and to reduce the risk of viral transmission to medical staff.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Mathur A, Mulvihill S, van der Laan L S-Editor: Huang P L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, Zhao X, Huang B, Shi W, Lu R, Niu P, Zhan F, Ma X, Wang D, Xu W, Wu G, Gao GF, Tan W; China Novel Coronavirus Investigating and Research Team. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727-733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18987] [Cited by in RCA: 17639] [Article Influence: 3527.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Dodig S, Čepelak I, Čepelak Dodig D, Laškaj R. SARS-CoV-2 - a new challenge for laboratory medicine. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2020;30: :030503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zhang YZ, Holmes EC. A Genomic Perspective on the Origin and Emergence of SARS-CoV-2. Cell. 2020;181:223-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 612] [Cited by in RCA: 511] [Article Influence: 102.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Weekly Epidemiological Update and Weekly Operational Update. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports/. |

| 5. | Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z, Yu T, Xia J, Wei Y, Wu W, Xie X, Yin W, Li H, Liu M, Xiao Y, Gao H, Guo L, Xie J, Wang G, Jiang R, Gao Z, Jin Q, Wang J, Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35178] [Cited by in RCA: 30106] [Article Influence: 6021.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 6. | Sohrabi C, Alsafi Z, O'Neill N, Khan M, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, Iosifidis C, Agha R. World Health Organization declares global emergency: A review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Int J Surg. 2020;76:71-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3213] [Cited by in RCA: 2654] [Article Influence: 530.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yeo C, Kaushal S, Yeo D. Enteric involvement of coronaviruses: is faecal-oral transmission of SARS-CoV-2 possible? Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:335-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 546] [Cited by in RCA: 554] [Article Influence: 110.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cai J, Sun W, Huang J, Gamber M, Wu J, He G. Indirect Virus Transmission in Cluster of COVID-19 Cases, Wenzhou, China, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1343-1345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 318] [Cited by in RCA: 335] [Article Influence: 67.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhang T, Cui X, Zhao X, Wang J, Zheng J, Zheng G, Guo W, Cai C, He S, Xu Y. Detectable SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in feces of three children during recovery period of COVID-19 pneumonia. J Med Virol. 2020;92:909-914. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 32.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wang Y, Wang Y, Chen Y, Qin Q. Unique epidemiological and clinical features of the emerging 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) implicate special control measures. J Med Virol. 2020;92:568-576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 972] [Cited by in RCA: 851] [Article Influence: 170.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chan JF, Yuan S, Kok KH, To KK, Chu H, Yang J, Xing F, Liu J, Yip CC, Poon RW, Tsoi HW, Lo SK, Chan KH, Poon VK, Chan WM, Ip JD, Cai JP, Cheng VC, Chen H, Hui CK, Yuen KY. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395:514-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6483] [Cited by in RCA: 5422] [Article Influence: 1084.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Rothe C, Schunk M, Sothmann P, Bretzel G, Froeschl G, Wallrauch C, Zimmer T, Thiel V, Janke C, Guggemos W, Seilmaier M, Drosten C, Vollmar P, Zwirglmaier K, Zange S, Wölfel R, Hoelscher M. Transmission of 2019-nCoV Infection from an Asymptomatic Contact in Germany. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:970-971. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2799] [Cited by in RCA: 2491] [Article Influence: 498.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, Tong Y, Ren R, Leung KSM, Lau EHY, Wong JY, Xing X, Xiang N, Wu Y, Li C, Chen Q, Li D, Liu T, Zhao J, Liu M, Tu W, Chen C, Jin L, Yang R, Wang Q, Zhou S, Wang R, Liu H, Luo Y, Liu Y, Shao G, Li H, Tao Z, Yang Y, Deng Z, Liu B, Ma Z, Zhang Y, Shi G, Lam TTY, Wu JT, Gao GF, Cowling BJ, Yang B, Leung GM, Feng Z. Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1199-1207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11224] [Cited by in RCA: 9315] [Article Influence: 1863.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Infection Prevention and Control of Epidemic- and Pandemic-Prone Acute Respiratory Infections in Health Care. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2014 . [PubMed] |

| 15. | Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, Liu L, Shan H, Lei CL, Hui DSC, Du B, Li LJ, Zeng G, Yuen KY, Chen RC, Tang CL, Wang T, Chen PY, Xiang J, Li SY, Wang JL, Liang ZJ, Peng YX, Wei L, Liu Y, Hu YH, Peng P, Wang JM, Liu JY, Chen Z, Li G, Zheng ZJ, Qiu SQ, Luo J, Ye CJ, Zhu SY, Zhong NS; China Medical Treatment Expert Group for Covid-19. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708-1720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19202] [Cited by in RCA: 18874] [Article Influence: 3774.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 16. | Tompkins BM, Kerchberger JP. Special article: personal protective equipment for care of pandemic influenza patients: a training workshop for the powered air purifying respirator. Anesth Analg. 2010;111:933-945. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ai T, Yang Z, Hou H, Zhan C, Chen C, Lv W, Tao Q, Sun Z, Xia L. Correlation of Chest CT and RT-PCR Testing for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: A Report of 1014 Cases. Radiology. 2020;296:E32-E40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3614] [Cited by in RCA: 3284] [Article Influence: 656.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Li Y, Xia L. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Role of Chest CT in Diagnosis and Management. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020;214:1280-1286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 662] [Cited by in RCA: 653] [Article Influence: 130.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bernheim A, Mei X, Huang M, Yang Y, Fayad ZA, Zhang N, Diao K, Lin B, Zhu X, Li K, Li S, Shan H, Jacobi A, Chung M. Chest CT Findings in Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19): Relationship to Duration of Infection. Radiology. 2020;295:200463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1728] [Cited by in RCA: 1597] [Article Influence: 319.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Notice on issuing a new coronavirus infected pneumonia diagnosis and treatment plan (trial version 5). [cited March 28, 2020] Available from: http://bgs.satcm.gov.cn/zhengcewenjian/2020-02-06/12847.html. |

| 21. | Zhou S, Wang Y, Zhu T, Xia L. CT Features of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pneumonia in 62 Patients in Wuhan, China. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020;214:1287-1294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 387] [Cited by in RCA: 451] [Article Influence: 90.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ti LK, Ang LS, Foong TW, Ng BSW. What we do when a COVID-19 patient needs an operation: operating room preparation and guidance. Can J Anaesth. 2020;67:756-758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 284] [Article Influence: 56.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wong J, Goh QY, Tan Z, Lie SA, Tay YC, Ng SY, Soh CR. Preparing for a COVID-19 pandemic: a review of operating room outbreak response measures in a large tertiary hospital in Singapore. Can J Anaesth. 2020;67:732-745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 434] [Cited by in RCA: 403] [Article Influence: 80.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Li LY, Gong YX, Zhang LB, Fu Q, Hu GQ, Li WG, Wei H, Hou TY, Deng MZ, Jiang YH, Yang XS, Suo JJ, Yang Y, Liu WP, Cheng SH, Zhang B, Cao B, Gao FL, Gao Y, Wang GF, Lu LH, Yuan XN, Zong ZY, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Zhou B, Zhao B, Yao X. Regulation for prevention and control of healthcare associated infection of airborne transmission disease in healthcare facilities WS/T511-2016. Zhongguo Ganran Kongzhi Zazhi. 2017;16:490-492. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 25. | Kamming D, Gardam M, Chung F. Anaesthesia and SARS. Br J Anaesth. 2003;90:715-718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wang YL, Zhu FZ, Zeng L, Telemacque D, Saleem Alshorman JA, Zhou JG, Xiong ZK, Sun TF, Qu YZ, Yao S, Sun TS, Feng SQ, Guo XD; Group of Spinal Injury and Functional Reconstruction; Neural Regeneration and Repair Committee; Chinese Research Hospital Association; Spinal Cord Basic Research Group; Spinal Cord Committee of Chinese Society of Rehabilitation Medicine; Spinal Cord Injury and Rehabilitation Group; Chinese Association Of Rehabilitation Medicine. Guideline for diagnosis and treatment of spine trauma in the epidemic of COVID-19. Chin J Traumatol. 2020;23:196-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |